Text

An Odonate Researcher from Sri Lanka Photographs a Spider While Looking for Birds in Malaysia - Observation of the Week, 7/21/19

Our Observation of the Week is this Gasteracantha diardi spider, seen in Malaysia by amila_sumanapala!

Amila Sumanapala first delved into bird watching when he was thirteen years of age and was growing up in Sri Lanka. “By late teens my interest had broadened to include a wide range of faunal taxa,” he says, “[and] I joined several volunteer nature organizations in the country such as the Field Ornithology Group of Sri Lanka, Young Biologists' Association of Sri Lanka and Butterfly Conservation Society of Sri Lanka and developed my capacity to become a researcher and a conservationist.” He is now a postgraduate researcher at the University of Colombo.

It was his original interest in birds that brought Amila and some friends to Malaysia, where they attended the Fraser's Hill International Bird Race. “My friend Kasun first observed the spider and showed it to me,” he recalls. “We recognized it to be a Gasteracantha species but it was different from what we have observed previously. So we photographed it hoping that we would be able to identify it later and we could do that thanks to INaturalist.”

Also known as spiny orbweavers, memebers of the genus Gasteracantha are found around the world as far north as the Korean Peninsula all the way to the southern tip of Africa. Gasteracantha diardi range through much of the islands of southeast Asia, and like other members of their genus, only the females are large and have spiked abdomens. Despite their diminutive size, Gasteracantha spiders spin quite large orb webs, and they decorate them with tufts of silk. It is presumed these tufts make the web easier for birds and other large animals to see and thus avoid, saving the spider from the onerous task of fixing a damaged web.

While Amila photographed a spider while on a trip where he looked for birds, his main area of interest is actually Odonata, or the dragonflies and damselflies. In about 2009 he developed an interest in them, and tells me

Most of my colleagues at that time did not know much about odonates, thus I started observing them by myself and studying them in detail using the available literature. This has now become the main interest in my life as a biologist and I am conducting various research on their taxonomy, ecology and biogeography. I also authored a field guide to the dragonflies and damselflies of Sri Lanka in 2017. My postgraduate work is also on the damselflies of Sri Lanka.

While he joined iNat in 2014, after hearing about it at the Student Conference in Conservation Science, Bangaluru, Amila (above, doing field work in Sri Lanka) says he’s only been using it regularly for about the last four months, “currently trying to document the insects I observe around the country using photographs and understanding their distribution patterns.

I started using INat to get identification support on the insects and other invertebrates I observe and photograph during my field work and it has been a great support in my work thanks to all the identifiers in the community. This has motivated me to record more and more biodiversity every time I'm out in the field and share it on iNat. I also contribute as an identifier, especially for Odonata and other major insect groups observed in Sri Lanka and India.

- by Tony Iwane. Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

- Check out this array of Gasteracantha species!

- Here’s a photo of a male Gasteracantha cancriformis. Note the lack of spikes.

- You can watch a Gasteracantha finish here web here. Note the little tufts of silk on the spokes.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sea Slugs on the Elkhorn Slough - Observation of the Week, 7/7/19

Our Observation of the Week is this Navanax inermis sea slug, seen in the United States by lmkitayama!

“At work they call me the Slug Queen,” says Lauren Kitayama, an Assistant Manager at Kayak Connection in California. “Daylight permitting, I paddle once a week before work on the Elkhorn Slough. A couple of years ago, if you'd asked any of the local guides they might have said there were 5 species of sea slug on the slough. Last year I documented 27!”

The slug seen above was one of twenty Navanax inermis she spotted that morning, and said they were mating on the sea lettuce near the dock at work. “They are one of my favorite slugs,” she says,

They are large enough for people to appreciate, and so absolutely beautiful! I love using them to get people excited about the unloved slimy things that live in the ocean. One of my goals is always to show people something they never even imagined existed on the planet, and Navanax are a great opportunity to do that. As a kayak guide I work with a lot of school children, and love having the chance to inspire them to protect and appreciate the natural world around them.

While nudibranchs are the most commonly known order of sea slug, the Navanax inermis belongs to an entirely different order: Cephalaspidea, or the headshield slugs. Most members of this order, including the California Aglaja, do have a shell, but it is usually either tiny or internal. Navanax inermis are large slugs, growing anywhere from 2.5 to 10 inches (6.35 - 25.4 cm) in length, and they prey upon other gastropods and even small fish!

Lauren (above) earned a Masters in Marine Conservation from the University of Miami (FL), where she focused on the impacts of marine debris. “I am zealous about protecting the oceans from plastic...[and] someday I hope to work for the UN attacking the plastic pollution problem in Southeast Asia.” For now, however, she says she loves her current job, and tells me

My favorite thing is to see something I've never seen before. "I don't know" is my favorite answer to the question, "what is it?" I think that's how this whole slug thing started. They are beautiful, and most people would never look for them/see them without a guide. For whatever reason my slug observation skills are great. Can't find my keys half the time (or the sunglasses that are on my head), but a 9 mm sea slug hiding in a patch of kelp... no problem.

With my ecologist brain, I am excited to continue documenting slugs on the slough to see if a temporal pattern emerges (when are particular species showing up? Are they predictably in the same locations year after year?) I try very hard to get a photo of every species I see every week so that I can continue to document their presence/absence on the slough.

- by Tony Iwane.

>

- Check out Lauren’s Litter Mermaid projects and blog!

- And her sea slug observations.

- Watch a Navanax inermis eating a California Seahare.

- And watch a pair mating!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leaf Litter Larva in Australia - Observation of the Week, 6/29/19

Our Observation of the Week is this Osmylops Split-footed Lacewing larva, seen in Australia by dhobern!

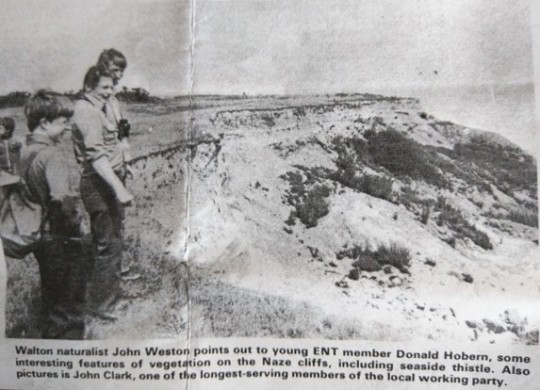

As a primary student in the UK, Donald Hobern remembers that his two school projects were “Animals” and “Wildlife,” explaining to me “my teacher forced me to expand the topic a little by including some plants.” Although interested in insects, he found contemporary guides lacking and thus got into birdwatching. “I also got involved in local naturalists' societies working on reserve work parties or watching over nests of Little Terns,” he recalls. “Here's a picture of me (on the left) from the local newspaper sometime in the mid seventies.”

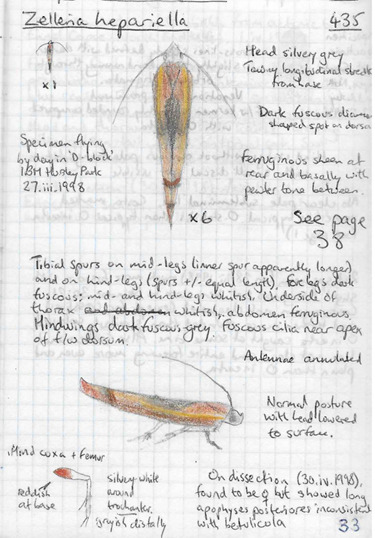

By the 1990s, Donald - equipped with the internet and improved field guides - got into mothing and graduated from sketching (below) to digital photography. He eventually started working for the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) in 2007, and says “since then, I've had the privilege of working on international efforts to improve access to biodiversity data (GBIF, Atlas of Living Australia, now International Barcode of Life and Species 2000). Personally, I've continued to study and photograph moths and pretty much any other species I encounter.”

One of those species, of course, is the remarkable insect at the top of this page. Looking for caterpillars in the Eucalyptus leaf litter by his home in Canberra, Donald placed some leaves in this emergence trap. “One of the first insects to appear, sitting on the inside of the upper plastic container was this larva,” he explains.

I would never have spotted it sitting on the surface of a leaf. Even on the clear plastic, at first glance, it could have been a dirty spot or some mould. The projections from the abdomen softened the shape considerably…

It mostly sat very still with the jaws completely drawn back and hidden behind the front fringe of the abdomen...At one point, it was sitting facing very close to the edge of the tin and an ant ran past in front of it. The jaws clearly snapped shut and hit the edge of the tin because there was a ringing noise and it was propelled backwards several centimeters.

Lacewings are members of the order Neuroptera, an order which includes other insects such as antlions and owlflies, and the bizarre (and totally cool) mantidflies. Split-footed lacewings, like this one, are actually taxonomically distinct from the more familiar green and brown lacewings, but like other neuroptera larvae, they have large mandibles and are predatory. After undergoing metamorphosis, they will look like this.

Donald (above, in Madagascar) has been an iNat user since 2012, and uses it to manage his own observations. He adds IDs to observations of plume moths, where he is far and away the top identifier, as well as Australian lepidoptera. “I greatly appreciate the expertise of others who amaze me with their wide international knowledge of groups I consider much more difficult than moths (beetles, true bugs, grasshoppers, etc.),

I also value the way that iNaturalist enables my observations and those of the whole community to contribute via GBIF to research questions, conservation and improving the knowledge base we need to understand biodiversity patterns and trends.

I continually recommend iNaturalist as far and away the best and most comprehensive platform to amateur naturalists and others to share their observations and learn from one another.

- by Tony Iwane. Photo of Donald Hobern in Madagascar by Kyle Copas.

- You can check out more of Donald’s photos on Flickr.

- Green lacewing larvae will cover themselves with debris - including the remains of their prey!

- This isn’t the first larval neuropteran that was chosen as Observation of the Week!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Parasitic Plant Rises from the Desert in Jordan - Observation of the Week, 6/24/19

Our Observation of the Week is this Cynomorium coccineum plant, seen in Jordan by fragmansapir!

Currently the scientific director of the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens, Dr. Ori Fragman-Sapir works “on endangered plants, flower bulbs, doing ecological and taxonomic research.” He also leads tours in Israel, the Mediterranean, and the Caucasus. While on an excursion to the southern part of Jordan (for his birthday!) this past April when Dr. Fragman-Sapir came across the small plant seen above. “It was amazing to see this parasite coming out of the dry sands, as if it was a miracle,” he recalls.

Those red stalks are pretty much the only parts of the plant one can see above ground, and they’re source of this species’ myriad common names, such as red thumb, desert thumb, and the bizarre (and misleading) Maltese fungus. A completely parasitic plant, Cynomorium coccineum contains no chlorophyll and spends most of its existence as a rhizome (an underground stem - think ginger or lotus “roots”), leaching nutrients and water its host plant, or plants. In spring the plant will send up its inflorescence, which is covered in tiny flowers. Flies are attracted to the cabbage-like smell of these flowers, and serve as the plant’s main pollinators.

Dr. Fragman-Sapir (above) has recently started posting his photos to iNaturalist, and hope it becomes a place where can have all of his “observations in one convenient place where others could enjoy and learn as well.”

- by Tony Iwane

- Dr. Fragman-Sapir has authored or coauthored several books, some in Hebrew and some in English, including Flowers of the Eastern Mediterranean.

- Many cultures have believed Cynomorium coccineum can cure multiple ailments, such as ulcers, anemia, hypertension, and impotence. It’s flesh is also edible as a food source.

- Check out this video about dodder, another type of parasitic plant, and watch it “choose” a host.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Chilean Flamingo and an America Flamingo Meet in Mexico - Observation of the Week, 6/18/19

Our Observation of the Week is this unlikely pair - a Chilean Flamingo on the right and an American Flamingo on the left - seen in Mexico by luisave!

About three years ago, an American Flamingo arrived in the Mexican city of León, Guanajuato, establishing itself in Metropolitan Park. It was around this time that Luis Mauricio Mena Páramo (luisave) began his bird inventory of the city. Since then, Luis has documented 188 species in the city (Mexico’s fourth largest), and on May 29th of this year he photographed a second flamingo in Metropolitan Park.

After discussions on both iNaturalist and in local birding fora, the second flamingo was confirmed as a Chilean Flamingo, a species that naturally ranges in the western and southern parts of South America and has been introduced in some parts of Europe and the United States. Luis’s photo is the first photo on iNaturalist of a wild Chilean Flamingo in Central America and well out of its normal range!

“So far,” explains Luis, “we have no knowledge or information about the possible origin and permanence of this bird

What we can know is that the American Flamingo that also inexplicably arrived at the Park more than three years ago has given it an excellent welcome. Perhaps it is a historical record, in which two wild Flamingos of different species coexist together and are very well adapted to each other.

Like other flamingos, the Chilean Flamingo uses the filters in this beak to feed on algae and invertebrates, and the carotenoids in their food cause the pink coloration of the birds’ plumage. Just one egg is laid per mating pair, and it rests on a raised mud nest. Both parents are able to produce crop milk to feed the young bird after it hatches.

Luis (above, at Metropolitan Park with both flamingos in the background) is turning his bird inventory into a book titled PRIMERA GUÍA DE AVES DE LEÓN, and he tells me “I use iNaturalist virtually every day in order to learn more about the world around me and also to share my observations with a community of naturalists...It is clear that without the support of the iNaturalist platform I would not have gotten this far...in my fifties I think it's been the best way to invest my free time, doing what I really like. It's a good way to transcend.

To this day, both flamingos continue to reside in the Metropolitan Park of León, and I have practically watched and photographed them every day. It has been amazing this story of adaptation to the urban environment and I feel very fortunate to share it with all of you.

- by Tony Iwane. Some quotes have been edited for clarity.

- A group of Chilean Flamingos “dance” in this video.

- Scientists have found that flamingos are more stable on one leg than two.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rhino vs Elephants in Namibia - (belated) Observation of the Week, 6/13/2019

Our Observation of the Week is this confrontation between a Black Rhinoceros and a group of African Elephants, seen in Namibia by jerrythornton!

Jerry Thornton, who grew up next to the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge but now resides in southern California, describes himself as “an amateur naturalist with a lifelong love of both nature and photography.” His wife, who is a freelance wildlife writer, will often research a topic and Jerry comes along to photograph her trip. They’ve been to Africa and South America, and also go scuba diving, “which we like to view as underwater safaris,” he says.

The dramatic series of photos you’ll see in this post were taken by Jerry during a tour of Nambia he and his wife went on back in 2014. They had stopped at the Moringa waterhole in Etosha National Park to and at first saw pretty standard waterhole behavior. However, after about half an hour a Black Rhinoceros approached. I’ll let Jerry take it from here.

The elephants began to get agitated as soon as the rhino arrived, even before it stepped into the water, with the elephants rapidly backing out of the water, ears fully extended, and bellowing much more than they had been just five minutes before. And they became even more agitated as soon as the rhino stepped into the water, forming the wall of elephants seen in the first of the photos.

As the rhino stayed longer and longer other elephant family groups would approach and then back off after seeing the rhino, sometimes their young males trying their luck at intimidating the rhino through bellows, ear waving, and as in the photo, even trying to blow water at them. Eventually one of the young males got too close and the rhino decided it had taken enough harassment, chased the offending elephant off in a cloud of dust, and then returned to the waterhole.

Unfortunately we could only watch this for about another hour, but the rhino was still soaking in the waterhole when we left and we had to assume it left on its own terms.

While it’s difficult to know exactly what motivated these behaviors, Jerry tells me he’s learned “elephants hate and fear rhinos, since they are one of the very few animals that can by themselves cripple or kill an adult elephant rather easily, and having a rhino so close to their young brought out their worst/most interesting behavior.”

Jerry (above) discovered iNaturalist recently, when trying to identify butterflies and flowers brought around by southern California’s rainy winter. “As I realized its potential for more accurately identifying all types of plants and animals,” he explains, “I began to post my past observations, with the goal of learning, and providing observations and photos for others.”

- by Tony Iwane

- Here’s an annotated video showing a Rhino and an Elephant with a bit of a misunderstanding.

- The New York Times has a nice article and video about an elephant’s amazing nose.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Feather Stars and the Wonderful Weirdness of Marine Invertebrates - Observation of the Week, 6/8/19

Our Observation of the Week is this feather star, seen in Indonesia by maridom!

“When I began diving some 25 years ago, I marveled at the beauty of sea life and was astonished to discover so many colors and forms, so many animals never seen on land,” says Maridom. “Then I became interested to learn more about the ecosystem and biology.”

And while she says most new divers think mainly about seeing fish, she likes to emphasize the beauty and diversity of marine invertebrates in when teaches marine biology courses. “I mostly am interested in phyla which seem weird to us terrestrial beings, such as Cnidaria and Echinodermata,” she says. “And during my last trip to The Philippines, I jokingly became known as ‘Queen of Ascidiacea’!

As soon as I see something beautiful under the sea, I point my camera to it and sometimes I come away with a successful photo! The photo of this Comatula this one of those: the colors are nicely contrasted and the shape of its arms are so delicately drawn.”

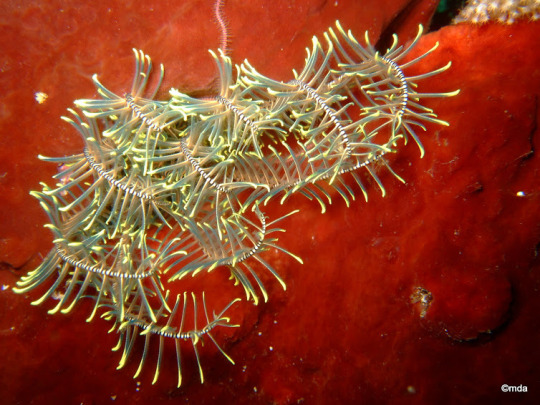

While sea stars and sea urchins are more familiar members of the Phylum Echinodermata, feather stars like the one Maridom photographed belong to a totally different subphylum called Crinozoa, which are also called sea lilies. They often have ten or more arms surrounding the mouth, and capture planktonic organisms with tube feet on the arms, moving the food down the arm in a blob of mucus.

Maridom (above, in Egypt) has been taking photographs on her dives for the last decade, and she tells me “it changed my way of diving and looking at living beings, even the small and weird ones, and I could not do without it now. Then, at home, trying to identify the species in my photographs brings back happy memories of the trip. I like to call things by their name while diving, as if I was part of their world.”

She discovered iNaturalist about three months ago, and has been uploading photos from her archive. “Each morning when I open my computer, the first thing I do is see if my unidentified strange things have now received an ID. Many thanks to all identifiers!

I love the way iNaturalist works, where all over the world, people keep connected and give from their personal time to help identify observations from others. I think, probably, when I was in The Philippines last month, it changed my way of taking pictures and looking at unknown things.”

- by Tony Iwane. Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

- Feather stars can swim and crawl, both of which look really cool and strange.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Birder Spots an Orchid in Algeria - Observation of the Week, 5/27/19

Our Observation of the Day is this sawfly orchid, seen in Algeria by karimhaddad!

Karim Haddad was born in the Algerian city of Constantine but pursued his graduate studies in Odessa, Ukraine, where he earned a PhD in Agribusiness. After being “very touched and inspired by the museums” at Ukraine educational institutions, Karim began to collect “some skins, horns, wood, sperm whale teeth, mollusk shells, old nests, unfertilized eggs, bird feathers, [and] butterflies,” and also got into bird photography.

He now splits his time between the two countries, and has been leading excursions for birders and other naturalists in Algeria since 2016, becoming Algeria’s representative for the African Bird Club in 2018.

And while birds and bird excursions are a specialty of his, Karim is interested in many other taxa, including orchids like the sawfly orchid he photographed above, which he says are “very exciting, their shapes, colors and sizes attract every naturalist. And that's why I never miss them...the world is so vast and interesting that it can be appreciated all together.”

Sawfly orchids are members of the genus Ophrys, which are also known as “bee orchids.” Members of this genus mimic the pheromones and appearance of female insects, attracting males of those species to the flower. While the male tries to mate with the flower (an act called pseudocopulation), its body picks up pollen which it then brings the next flower, pollinating it. Supposedly the sawfly orchid resembles a female sawfly, which are members of the hymenopteran suborder Symphyta. This orchid is found throughout much of the Mediterranean.

Karim (above, in Constantine c. 2015) is also part of the AquaCirta NGO in Algeria, which chose iNaturalist as a recording platform last year on the recommendation of Dr. Mehdi Chetibi. Since joining last July, Karim has contributed over 4,000 observations and 60,000 IDs to iNaturalist (with archives from his computer still waiting to be uploaded), and he says the direct contact with amateur and professional naturalists from all over the world has “changed my way of interacting and seeing the natural world...

With iNaturalist, you share, you learn, you get to know people and you can rejoice with discoveries. So, I propose this site for all amateurs and specialists without exception in the world of nature.

- The Natural History Museum has a nice video describing pseudocopulation in Ophrys orchids here.

- Here are Eucera nigrilabris bees pseudocopulating with a sawfly orchid.

- Finally, a more poetic and philosophical take on pseudocopulation from the film Adaptation.

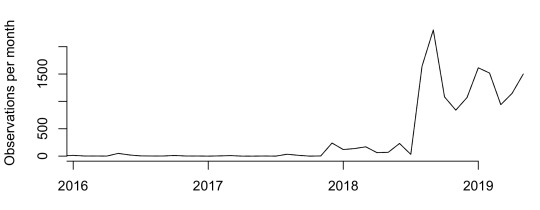

- This chart of observations per week in Algeria shows the large impact Aquacirta’s promotion of iNat has had. Thank you so much!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Helmeted Iguana Hangs Out in Colombia - Observation of the Week, 5/21/19

Our Observation of the Week is this helmeted iguana, seen in Colombia by khristimantis!

“I was in a field trip accompanying a herpetology course in a natural reserve called Hacienda San Pedro,” recalls Khristian Venegas Valencia, a biology student at the University of Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia. The reserve is located in the Magdalena Medio, which Khristian says “is today one of the regions most affected by livestock in Colombia [and] a large part of the forests and ecosystems of the region have been reduced or almost completely disappeared. However, thanks to the initiative of some people it is possible to find some relicts of forests that function as sanctuaries and natural reserves that allow the conservation and care of nature.”

During their time in the reserve, Khristian, who is interested in the ecology, conservation, systematics and taxonomy of neotropical amphibians, and his colleagues made some great finds, such as glass frogs and a terciopelo viper. Then,

coincidentally, following the advertising call of a frog of the genus Pristimantis, I came across the [helmted iguana] perched on a branch. It was a fascinating encounter since these organisms are quite difficult to observe and I had not had the opportunity to register one before.

Usually found in trees (when they are found), helmeted iguanas - also called casque headed lizards - rely on the sit-and-wait method of predation, often staying in one place for extended periods of time until suitable prey such as insects, spiders, or other lizards approach. Their lack of motion, in addition to their camouflage, allows these lizards to go unnoticed by both their prey and their predators. Both males and females have a “helmet”, but the male’s is slightly larger.

“I have always been interested in scientific divulgation and the transmission of information to the community in general,” says Khristian (above, with a helmeted iguana). “I use iNaturalist as a documentation tool and as a source of learning about biodiversity in my country.”

- Helmeted iguanas have been found with plants and fungi growing on them, likely due to their proclivity for remaining motionless for extended periods.

- Slime mold sporangia have also been found on a heleted iguana! [PDF]

- If you have always dreamed of seeing a helmeted iguana remain motionless while ants crawled on it and epic choral music swelled in the background, you’re in luck.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Common Hoopoe forages in Prague - Observation of the Week, 5/12/19

Our Observation of the Week is this Common Hoopoe, seen in the Czech Republic by lioneska!

“A few years ago, I became seriously interested in birds thanks to one of my friends,” says Gabi Lioneska Uhrova. It took me a long time though to get to know them…[but] I can say that I’ve become a loony (crazy) in observing them and I started to take pictures of them too. I’ve also become a member of the Czech Society for Ornithology.”

After hearing about a Common Hoopoe sighting in Prague, Gabi decided to check out the area after work the next day and started scanning for the bird with her binoculars. After some time she stumbled across it on the path in front of her, no more than twenty meters away, and watched it pick up an insect.

My heart jumped with joy. “Ohh, you are so beautiful, little bird,” I thought to myself. The advantage was that it was quite tame, and its escape distance was short. When disturbed it would fly on a tree and then continue to forage for food again.

Later on a friend of mine, Tereza, joined me to take picture of it. My goal was to lie down and take a picture of it in its natural habitat, grass, which I managed to do thanks to its tame behaviour. After that we just sat there and watched this amazing bird using its long thin beak as tweezers. We were simply so lucky. This is one of my most precious bird observations because I had not seen one in a long time and it is a rare species for me. I was really grateful for this opportunity.

The Common Hoopoe ranges through much of Europe, Asia, and the northern part of Sub-Saharan Africa, and as Gabi described, it likes to forage for insects in flat grassy areas. Much of the foraging is done with its long thin beak, with which it probes the ground for insects, and it will raise the crest on its head when excited. Hoopoes nest in tree cavities, or really any cavity on a vertical surface.

In addition to birds, Gabi (above, on the right) loves to photograph and observe butterflies. “During spring and summer season I often make trips to different types of habitats to watch them,” she says. “It isn’t easy to take a good picture of them; it’s always a challenge but I love it, I take my time and enjoy it.”

Gabi first discovered iNaturalist during the 2018 City Nature Challenge, and tells me “Now I upload most of my observations of nature [to iNaturalist]. Sometimes there is no time to do it all at once. I love the application because it is so simple to use, and I have overview of all my observations at one place...If I see a beetle or other interesting insect or a flower, I take picture of them too and post it to iNaturalist or Facebook groups that we have in my country for determination.”

- by Tony Iwane. Some quotes were lightly edited for flow.

- An adult hoopoe feeds its young - in slow motion!

- Some nice footage of foraging hoopoes.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Ovipositing Wasp in Russia - Observation of the Week, 5/3/19

Our Observation of the Week is this ovipositing Atanycolus wasp, seen in Russia by ropro!

In my experience, most people associate the word “wasp” with members of the Vespid family, such as hornets and paper wasps. And for good reason, as many of them are large, colorful, often found around humans, and can deliver a painful sting. But the world of wasps is endlessly fascinating, and that includes parasitoid ones such as the Atanycolus wasp seen above.

The photographer, Roman, tells me he came across this individual during mid-August, and it was one of several braconids he found on a fallen birch tree. Fallen birches, he says, are often great places to find wasps, “from Giant ichneumon wasps (Megarhyssa) to such small ones (the one in the picture, about five millimeters). Therefore, if I see a fallen birch, then I will definitely look at it.”

Why so many wasps around an old tree? Well, that’s where they can find food and a home for their young. Many other insects, such as long-horned beetles and some species of lepidoptera, lay their eggs here, and their larvae bore through the wood. Wasps like the Atanycolus photographed by Roman take advantage of this by using their long ovipositors to “drill” into the wood and lay their eggs on these larvae. The wasp larvae then parasitize the larvae of the other insects, either internally or from the outside, and usually wind up killing their hosts. This mother wasp, in fact, was so focused on her work, that Roman explains “it was easy to photograph, because the braconids did not react to my close presence and were inactive. The only difficulty was their small size.”

Always interested in nature, Roman says that ten years ago he bought a digital camera and, “after moving to a new place of residence, where was a large park nearby, I began to photograph insects, plants and birds there.

I have recently started to upload my own observations [to iNaturalist] and I [have] became interested in butterflies and moth of Central and South America here. They are very unusual there [and I am] trying to identify them.

- by Tony Iwane.

- PBS’s Deep Look has a nice video explaining Megarhyssa oviposition.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Mass Emergence of Cottonmouths - Observation of the Week, 4/21/19

Our Observation of the Week is this large group of Cottonmouths, seen in the United States by wildlandblogger!

A few weeks go, while on a hike in a central part of North America, looking for birds and plants Jared Gorrell had gotten a bit lost but was able to use his phone’s GPS to navigate back to his car. However, something caught his eye. “I noticed a pond along the way and decided to look around it and see if I could find some birds, insects or plants that would be new for me,” he recalls.

I didn’t realize the pond had dirt cliffs around it, and as I walked downslope I nearly stumbled over the edge of one of these, and then I looked down into that pile of cottonmouths. I backed up and sat down, and then proceeded to put my hand down six inches from a juvenile cottonmouth. After moving it out of the way with a long stick and then going uphill to have a slight panic attack over the close call, I came back down to take pictures and count.

You definitely don’t want to get bitten by a cottonmouth, which is a viper endemic to the United States. While fatalities are rare, this species’ cytotoxic venom can cause severe tissue damage and pain. Although it has a fierce reputation, this snake (like most others) is not aggressive (PDF) and will choose to either escape or engage in threat displays when encountering a human. One of those displays involves showing off the bright white interior of its mouth, giving the species its common name (although it’s also known as a water moccasin, as well). These semi-aquatic snakes eat a wide variety of prey and are often found near water sources, although usually not in such large numbers.

“What you see in the photo is a pile of sunning cottonmouths that have recently emerged from a den site, presumably someplace on a nearby hill,” says Jared.

In this temperate area, snakes form groups like this in sunny spots to warm up more quickly, after leaving a cool underground refuge where they spent the previous winter. Unfortunately, many of these “mass emergences” have been targeted by locals afraid of venomous snakes, so this “ball of cottonmouths” is a rare sighting nowadays, and I’ve intentionally kept the location private for that reason...since poaching and/or harassment are serious issues for reptiles like these cottonmouths, I generally obscure or privatize my herp locations.

Jared, who tells me “at three years old I spoke vaguely with an Australian accent because I watched Steve Irwin, the Crocodile Hunter, so often,” will soon be graduating from Southern Illinois University - Carbondale with a degree in plant biology specializing in ecology, and this summer plans on “working with the Critical Trends Assessment Program in Illinois surveying plants and insects at various field sites across the state.”

And during his free time, Jared’s out and about looking for plants, birds, reptiles and amphibians, and has “recently developed an interest in dipnetting for fish and netting for dragonflies and butterflies.” He uses iNat to “log all of my sightings, compete with friends, and share my observations with those around me. iNaturalist has inspired my interest in dragonflies, butterflies and fish, especially fish since they’re so under-reported on this website. I definitely take a lot more pictures now too!”

- by Tony Iwane

- Bird and Moon has a great comic about the myths and facts surrounding cottonmouth snakes.

- Here’s thorough advice on how to survive a snakebite in the wilderness. (Disclosure: I previously worked with Jordan Benjamin, founder of The Asclepius Snakebite Foundation)

- Water snakes of the genus Nerodia are often mistaken for cottonmouths. The University of Florida has a nice resource showing you how to differentiate them.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Long-ago Butterfly in Thailand - Observation of the Week, 4/15/19

Our Observation of the Week is this Long-banded Silverline butterfly, seen in Thailand by lesday!

If not for “a very nasty motorcycle accident” a few months ago, it’s possible the photo you see above would not have been posted on iNaturalist. But we’ll get there. Let’s go back more than five decades, when Les Day was a child in Britain and he collected “a small british moth, called the Brimstone, in a bucket at home.” With the help of his parents, “who often drove me out into the countryside, to look for insects,” Les eventually focused on butterflies, which “continued to be the main object of my curiosity.”

Fast forward to 2007, when he emigrated Thailand’s Ko Samui island in 2007, and Les continued to concentrate on butterflies, including the male Long-banded Silverline butterfly that is the subject of this post. “It is not uncommon on Koh Samui, but usually it is found with wings closed,” he says. “The opportunity to photo the upperside of the species, particularly the more flamboyant male, does not come that often.” Members of the family Lycaenidae, or gossamer-winged butterflies, the underside of its wings are not too shabby either - a real stunner. It is thought that the eye spots near the antenna-like projections of its hindwings act as a “false head”, causing predators such as birds to attack the insect there rather than its actual noggin.

After finding most of the butterflies that resided on Ko Samui, Les “needed something else to occupy me during my daily walks in the hills away from the tourist areas.” After doing some research he realized that the Hemiptera of Thailand were not well known so he decided to shift his focus from butterflies to bugs - specifically Cercopoidea (froghoppers), which “seemed very interesting and in much need of study.”

Which leads us to iNaturalist and that motorcycle crash.

“I started using INaturalist a couple of years ago on the advice of a friend, but I only posted a few moth photos then,” says Les (above). And I will let him tell the story from here.

It took a very nasty motorcycle accident on the Thai peninsular mainland a couple of months ago for me to re-evaluate the importance of my photos. I had already been advised by researcher friends at various museums and universities around the world that many of my hemipteran photos were species new to Thailand and furthermore, there were quite a few totally undescribed species as well. Whilst stuck at home, unable to go out in the field, I realised that these photos would be lost if anything more serious should happen to me, as they were kept on my hard-drive and on my personal website, both of which would be lost after a year or so. I needed to find somewhere where they would remain available to researchers and the general public and iNaturalist came to mind, so, since I have been holed up at home recovering, I have been placing nearly all my photos on iNaturalist. I have been fortunate that some new identifications have been forthcoming from informed identifiers for which I am very grateful.

I have nearly finished posting my old photos, just about 1500 butterfly species and subspecies left from around S.E.Asia. Once finished, it will be easy to update daily findings when I am finally able to go out into the field again.

- by Tony Iwane.

- The larvae of Long-banded Silverlines are associated with ants, as seen in this video. Check out its reaction when an ant gets too close to its posterior!

- The photo of Les is was taken by Johnny Patterson, for this article.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Holy Mola! - The Oral History of an iNat Identification

The iNaturalist community made international headlines a few weeks ago after the first hoodwinker sunfish (Mola tecta) seen in North America was shared and then identified via iNaturalist and some dedicated participants. It really is a great story that shows the power of collaboration and the importance of keeping an open (and optimistic!) mind, so I thought it would be fun to compile an oral (although in this case, written) history from the participants.

What follows are the lightly edited and condensed recollections of most of the people involved, put together as chronologically as possible. I have not heard back from all participants, but am happy to add your input if you message me.

Jessica Nielsen (Coal Point Oil Reserve): My first observation of the hoodwinker sunfish was on the morning of February 19th, 2019. A colleague, Mark Holmgren, and I were conducting the reserve's monthly bird monitoring survey at around 7:00 am and noticed a tall dorsal fin flopping about in the water about a hundred meters off of the point at Coal Oil Point Reserve. We weren't sure at the time what animal we were looking at as we couldn't see it very clearly in the water, but we assumed it was some kind of marine mammal based on the size of the fin and head. Later the same day, when a 7 foot long sunfish washed up on the beach, we realized that was what we had seen that morning.

I was alerted to the washed up fish by one of our UCSB student interns, Ruth Alcantara... Unfortunately, the fish was already dead but it was still a sight to see such a large and unusual fish up close. I took some measurements and photos and posted the finding to Coal Oil Point Reserve’s Facebook page.

Daniel Spach (Wilderness Youth Project): We were about to leave Devereux that day after tidepooling for a couple hours when a couple of the kids spotted what looked like a dead seal or something in an unusual posture near the beach on the rocks. When we got over there we were stunned to find something I had never seen or heard of anyone finding on a Santa Barbara beach... a Sun Fish? It was longer than I am tall, over 7 feet I'd say, super flat and roundish, with a mouth big enough to swallow my head. All the kids gathered round and were giddily excited about it, noting the shape of the fins and eyes, making guesses as to its watery demise. Everyone seemed a bit scared to touch it though, thinking it would be slimy like most decomposing fish we'd encountered but it's skin was actually extremely hard, dense, and rough, like an ocean rhino or something.

Kittyhawk snapped a few pictures [TI: see above] with her phone. The kids all wanted to make sure their parents would get a copy of the pictures. Might be the only time any of us will encounter this fish for our lifetimes.

Jeff Phillips (@ljefe): My 10-year old son Pierce participates in the Wilderness Youth Project’s after school program every Wednesday. [On] Feb 22, when I met the group to pick up my son and friends at 5:30pm, they were excited about this huge fish they had found on the beach during their afternoon outing (sometime between 2 and 4:30pm). I’m a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service so they knew I’d be excited about it. I had them send me the photo and with my son’s help to mark the location, I posted it on iNaturalist, originally identifying it as Mola mola. I thoroughly enjoyed the ensuing discussion among tomleeturner, rfoster, and mnyegaard.

Tom Turner (@tomeleeturner): I saw [Jessica’s] post and went down there with my family, because I wanted my 4 year old son to check it out. I posted it on iNat, of course, because…that is what I do. Everyone was assuming it is a Mola mola. What happened next is a classic example of iNat at its best.

Ralph Foster (@rfoster): I have an alert for Mola spp and was checking through the day's offerings when I saw what I took to be a stranded Mola tecta. I was bewildered when I realised this was in California and not in New Zealand or Australia so I tagged Marianne [Nyegaard, who described Mola tecta], asking for her input.

Marianne Nyegaard (@mnyegaard): Ralph Foster emailed me with links to iNaturalist asking if I could see what species it was, strongly suspecting it was Mola tecta. I quickly checked and thought that the fish surely looked like a hoodwinker, but frustratingly, none of the many photos showed the clavus [TI: aka what sunfishes’ back “fin” is called] clearly. And with a fish so far out of range, I was extremely reluctant to call it a hoodwinker without clear and unambiguous evidence of its identity... I emailed Ralph and told him we needed more photographs and ideally a tissue sample, and posted on iNaturalist that his was probably just a Mola mola.

Ralph Foster: Since there were no diagnostic features shown, I also tagged the observer (@sealovelife) asking if there were more images available, which is when Tom directed me to his observation.

Tom Turner: By this time I was already out on the beach in the dark looking for the fish to get better photos, because what could be more fun than this? Alas, the tide had floated it away again.

Marianne Nyegaard: I then had a cup of coffee and doubt starting creeping in... I spent the next few hours obsessively zooming in on all the photos posted on iNaturalist... Some photos showed peoples’ hands on the sunfish, so I used their fingernails to gauge the scale and compared the skin with my archive photos. Even though the resolution just wasn't high enough to be sure, I started convincing myself the skin at least wasn't incompatible with Mola tecta and that ….perhaps it was a hoodwinker?... But I felt I needed to be absolutely 100% sure before settling on an ID, seeing I had described the hoodwinker and would need to back up my ID with absolute certainty with a specimen so far away from home.

I woke up to an email from Jessica Nielsen saying [she and Tom] were keen to go back out and find the fish again so I sent them instructions of what to look for and photograph, and then sat on the edge of my chair with all fingers and toes crossed that they would find it.

Tom Turner: At low tide (now two days later), I started biking on the beach from the east, and Jessica started walking from the west, 2 miles apart. We met in the middle, at the fish, now a few hundred yards farther east.

Jessica Nielsen: Tom and I waited for the tide to go out, found the fish...and we got to work taking the photos and fin clips requested. It really was exciting to collect the photos and samples knowing that it could potentially be such an extraordinary sighting! Once we sent over the photos, Marianne responded very quickly.

Marianne Nyegaard: I was away from my desk most of the day, but when I checked my emails in the afternoon I literally nearly fell off my chair (which I was sitting on the edge of!). Tom and Jessica had indeed found the fish and had photographed and examined it, and taken a tissue sample. A huge amount of extremely clear photos were in my inbox and there was just no doubt of the ID. They had also examined the clavus by hand to confirm the number of ossicles, which was just brilliant. Eyes and ears and hands on the ground half a world away, wow.

Ralph Foster: If it hadn't been for Tom and Jessica's willingness to revisit and examine the specimen we would not have known with certainty that this was, indeed, Mola tecta.

Jessica Nielsen: We were all thrilled to hear the news. Mola tecta was just recently discovered in 2017 (by Marianne and her research team) so there is still so much to learn about this species. I’m so glad that we could help these researchers make the final definitive ID.

Tom Turner: iNaturalist at its best: experienced novice loops in expert who loops in the expert who then helps us learn about our find and gets info she will use in her research. And it was fun and exciting for all.

Marianne Nyegaard: Ralph Foster also alerted the University of California, who did a beach dissection and collected a large number of samples. Tissue samples will soon be on the way from California to my sister’s lab in Denmark, where I do all my sunfish genetics.

So, within 24 hours after I had first been made aware of this stranding we had confirmed the ID. I just love iNaturalist and am continuously amazed by how much fun it is to “meet” passionate people all over the world

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slime Mo(u)lds in Tasmania - Observation of the Week, 3/18/19

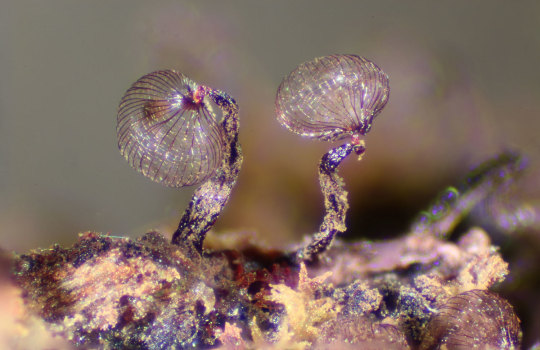

Our Observation of the Week is this Cribraria cancellata slime mold, seen in Australia by sarahlloyd!

If you’ve uploaded a slime mold observation to iNaturalist recently, there’s a good chance that Sarah Lloyd has identified it. She’s our top slime mold identifier, with over 1,500 IDs added, and she only joined in November of 2018. But Sarah’s interest in slime molds (or “moulds” depending on where you learned English) is relatively recent, beginning in 2010. “After beginning a routine of daily morning walks I started to notice and photograph plasmodia (the second feeding stage of a slime mould) or their exquisitely miniscule spore-bearing fruiting bodies,” she says, “[And] I was hooked! By September that year I was closely examining logs and stumps with a hand lens and strong headlamp, essential equipment for seeing the fruiting bodies in the darkness of the shady forest—and I started to accumulate reference books.” She soon began to collect them as well.

Slime molds (Myxomycetes), as Sarah notes, “have mystified naturalists for centuries.” Originally classified as plants by Linnaeus, they were moved to fungi, then to animals, and

there is now general agreement that myxomycetes are Amoebozoans but whether this is a supergroup or kingdom is a matter of debate...Their predatory amoebae live in soils rich in organic matter where they feed on bacteria and single-celled fungi such as yeasts. Thus, they play important ecological roles including enhancing soil fertility through nutrient recycling….[and] despite being found wherever there is organic material, they are believed to be the least studied of all the microorganisms.

Amoeba-like when separate, individual cells will join together to form a plasmodium and eventually form rigid spore-bearing structures called a sporangia, which is what you see photographed above. Sarah notes that “slime mould fruiting bodies are never fleshy, but are essentially a mass of spores. They (and substrate) dry within hours and retain indefinitely all features needed to describe them.”

Sarah observed the Cribaria cancellata sporangia “on a log of a severely decayed silver banksia...part of a very extensive group of thousands of sporangia that covered 40 x 10 cm (16 x 4 inches).” She says they were about 1.5 mm in height and

[the species’] colour and distinctive ribs makes it one of the few species of slime moulds that can be identified in the field with the aid of a 10x hand lens. Unusually for a slime mould, the species appears in the same location each year and has stained the decaying wood a deep maroon colour.

Sarah (above, inspecting a slime mold), tells me

I enjoy interacting with people and identifying their slime moulds photos on iNat. People are often intrigued to find out more about them – and to find more slime moulds to photograph. Through people’s posts I can learn about species that occur in other regions of the world and see photos of myxomycetes I’ll never see in Tasmania. As an avid naturalist passionate about documenting Tasmania’s biodiversity, it’s fantastic to be able to contribute (via iNat) to biodiversity monitoring projects elsewhere in the world from the middle of a forest in Tasmania.

I have recently started to upload my own observations of slime moulds and many other species, something that should keep me well occupied for many years to come.

- by Tony Iwane.

- Check out Sarah’s Tasmanian Myxomycetes site, as well as her Instagram account!

- And her book, Where the slime mould creeps!

- Slime mold time lapse!

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Mighty Snail Found in Ecuador - (Bonus) Observation of the Week, 3/14/19

Our (Bonus!) Observation of the Week is this large Thaumastus thompsoni snail, seen in Ecuador by souhjiro!

Edgar Segovia (@souhjiro) is a biologist who has a lot of interests, “mainly entomology, arachnology, carcinology and malacology, and I am also interested in aquatic biology and ecology.” His curiosity with nature started at an early age, when“[I] saw as child the insects on the garden or on my school patio, and the tadpoles on the puddles around my natal city of Cuenca...and compared them with the Atlas of the Animal World, from Reader´s Digest, which was my first and favorite book.” Even at at that young age, Edgar noticed detail such as the local frogs, mainly of the genus Gastrotheca, did not lay eggs like those he saw in the book.

As he grew older, Edgar was mentored by biologist Gustavo Morejon, who lent him books and showed him Universidad del Azuay’s insect collection. “As a 12-something year old boy, [I] was totally fascinated with that, and that furthered my interest on following a biology career,” he says. “I worked in ecological assessments with land insects, and also limnology studies in different places of my country, knowing meanwhile a lot of terrestrial and aquatic insects and macrofauna (including fish and herps) from Ecuador. Lately, I had the opportunity to spend some time at the Charles Darwin Station, and could be in contact with the insects of Galapagos Islands in the flesh (or carapace).”

Edgar saw the snail pictured above (which, he notes, has a shell about 8 cm in length) not recently but actually way back in 2004, while instructing rangers at Sangay National Park. Tasked with teaching collection techniques for herpetofauna and invertebrates, including pitfall traps, he recalls

One drizzly morning, revising the pitfalls, among the Chusquea bamboo surrounding one of the traps, a big snail appeared. [Everyone] there was very excited, and we put it on a tree trunk to photograph it. For a time, we forgot about the pitfalls (then remembered and continued). The snail received a lot of flashes while all those with cameras photographed it, and I used the opportunity to talk about our very much neglected terrestrial malacofauna to the rangers.

This was not his first time encountering Thaumastus thompsoni. In fact, in 2002 he assisted Brazilian scientist Meire Pena when she was collecting specimens in the Azuay province. This species, says Edgar, “is associated with Chusquea and mixed chaparro forest patches on Andean Cañar and Azuay, and currently is under threat of habitat destruction for cattle farming, pasture opening, and fast urbanization, but that threat is not yet assessed properly. Great thrushes eat the snails, and sometimes near rock outcroppings their emptied and broken shells are found.” When he recently passed through this area, Edgar noted that the forest had regained some territory since 2004, and shells on the ground indicated that thes snails still inhabit the area.

As for iNaturalist, Edgar (above, in Plaza Sur, Galapagos), heard about it from Gustavo Morejon, his old mentor, and he says

the [iNaturalist community] accelerates the process of ID, and there are some specialists and experts on there...it motivates me to publish more observations on the web instead to keep them archived, and is even fun to stroll a walk taking pics of every interesting critter or plant in the path.

- by Tony Iwane. Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghost Flowers in the Sonoran Desert - Observation of the Week, 3/8/2019

Our Observation of the Week is this Ghost Flower seen in Mexico by micrathene!

“My parents met taking an adult birding class and they encouraged me to be interested in the natural world,” says Arizona ornithologist David Vander Pluym. “Some of my earliest memories are of new birds (and being a grumpy 3 year old about missing a life bird).” While birds remain his primary focus, David’s grown more interested in other taxa and will even branch out into collecting spider specimens this spring. And plants? “I've only been interested in flowers for a few years (after my wife got me interested in actually looking at plants) and still know next to nothing about them.”

However, ghost flowers (Mohavea confertiflora) have quickly become one of David’s favorites and he’s even found them in the parking lot of a bar! The plant photographed above (and below), however, was seen while on a trip to Reserva de la Biosfera El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar, on the way back from a trip to Puerto Penasco, Sonora “celebrating a couple of friends' birthdays as well as an excuse to look for birds, go tidepooling, and look for whatever else we might be able to iNat.”

The group, which included David’s wife Laura and fellow iNatter Ryan O'Donnell (@tsirtalis), were hiking up Cono Mayo when Ryan pointed out the flowers to Laura, “who identified them and called to me, who had walked right passed it! I looked back and noticed there was a small patch of them (I counted more than 50) near where they were looking and I quickly started photographing them. I think this one was one of the first I noticed and took a photo of.”

Native to the deserts of southwestern North America, ghost flowers do have a translucent “ghostly” look to them, and David says “the number of plants out and the size and number of flowers on a single individual varies year to year too with local rainfall.” Interestingly, ghost flowers do not produce nectar but, according to the California Native Plant Society, are pollinated by Xeralictus bees, which also pollinate sand blazingstar flowers - a species that often grows in the same area. These bees are drawn to ghost flowers because the “flowers contain marks that resemble female Xeralictus; these marks operate as a sign stimulus to the male bee, which enters the flower and in doing so pollinates the Mohavea.”

David (above, in Álamos, Sonora with another non-bird organism) tells me that while he has used iNaturalist to quickly identify plants when he’s birding, he really iNats “as a way to learn more about other forms of life beyond my main focus. Being able to share sightings and have an identification made on some random organism I photographed has made me want to pay a lot more attention to other organisms I probably would have previously passed by. Being able to identify and put a name on something is a powerful thing.”

- by Tony Iwane

- Micrathene is a genus of owls which contains but one species, the elf owl, a bird that David has studied.

- It’s shaping up to be a good flower year in the deserts of southwestern North America. If you go, please tread lightly!

10 notes

·

View notes