Text

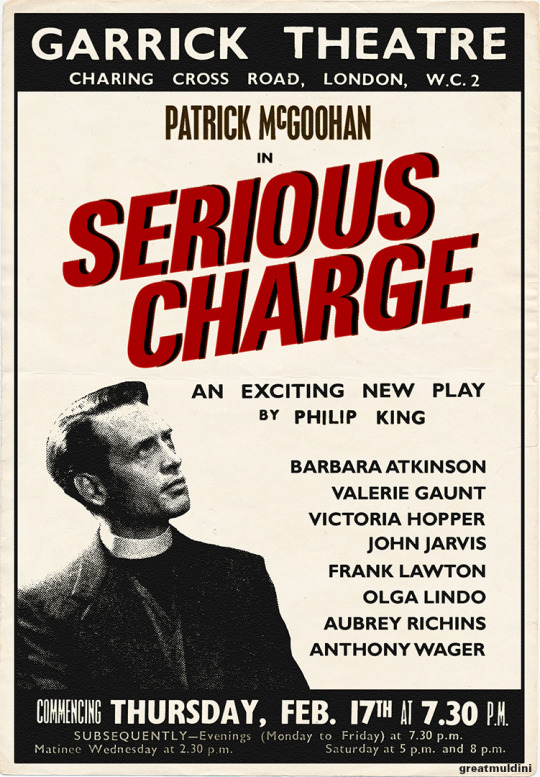

The Iron Harp

We’re all in prison together, Johnny, one way or the other.

Act 1

Outwardly, Joseph O'Conor's play is a simple tale of love and loss in times of war: set in rural Ireland in early April of 1920, the action takes place on the property of an English industrialist whose mansion has been taken over by a contingent of IRA volunteers. Their leader is Michael O'Riordan, a gifted poet-musician in civilian life and conveniently the peace-time manager of the Englishman's estate. Michael has recently been wounded in action; now blind as a result he is no longer on active duty but still responsible for an English prisoner of war. Being a man of his word, Captain John Tregarthen has made no attempt to escape, earning Michael's trust and eventually his friendship. He also earns the friendship and love of Michael’s cousin Molly Kinsella, with whom he spends long days roaming the extensive grounds of his idyllic prison. Dreaming of a future life together, the lovers are oblivious to the feelings of their “best friend” – who ends up sacrificing his love for Molly in what he hopes will be a lasting gesture of selflessness only to find that Fate intervenes, with devastating consequences for them all.

Completing the quartet of characters is the dark and “indistinct” figure of IRA commander Sean Kelly, a dark and "indistinct" figure who emerges from the shadows to immediately assert his authority not only in military matters but - crucially, and disturbingly - in those of the heart as well. Specifically, it is the heart of Michael O’Riordan that Kelly claims to know better than O’Riordan himself. As a flesh-and-blood character Kelly is difficult to pin down: cold and calculating by his own admission, he expresses admiration for Michael's hot-blooded fighting spirit. Michael's own startled response to Kelly entering "like Nemesis himself" is ambiguous at best, and even his description of Kelly as a “good friend” comes on the back of a warning to Johnny that "he won't like you."

When Kelly tells Michael that he has never been wrong and does not know what it means to feel regret, the sense of foreboding is inescapable, yet Michael never seems to give in to the negativity emanating from his old wartime comrade who admonishes him to see his friends “as they really are” and not as “you want to see them.” Ironically, Michael refuses to see an enemy in John Tregarthen, but he is equally stubborn in applying the same criteria of honour, loyalty, and friendship to Sean Kelly, who seems troubled by this flaw in Michael’s character: "you love people too much."

Michael's emotional warmth stands in stark contrast to Kelly's impersonation of infallibility - which Michael seems to accept as a token of his friend's unassailable integrity. He continues to defer to Kelly's judgment when a messenger arrives with bad news from the front: three IRA fighters have been killed in skirmishes with British forces, and reprisals must be carried out. Twisting the metaphorical knife in the very real emotional wound, Kelly as the commanding officer nominates blind Michael to be the impartial instrument of God's justice. Forced to select three victims for execution, Michael all but collapses when one of the chosen names is that of Captain John Tregarthen.

Act 2

After he has persuaded Johnny to flee the country and reunite with Molly back in England, Michael is left alone to guard the now empty house. Blind and unable to defend himself, Michael is powerless against two marauding Black & Tans who break into the property and proceed to taunt and abuse the solitary occupant. It does not take them long to realize their victim is an IRA member rather than a civilian enjoying certain protections. Further violence is prevented only by the surprise return of Captain Tregarthen, armed and in uniform, who holds the attacker at gunpoint until Kelly and his entourage arrive to take the men away. Where any other human being would have expressed relief or gratitude at the discovery that the life of his friend has been saved, Kelly’s reaction is characteristically impassive, betraying, if anything, a degree of irritation at the unforeseen complication that has shown the condemned prisoner – the enemy – to be capable of compassion and self-sacrifice in saving the life of his friend. Human qualities that Kelly explicitly claims not to possess. As if to prove the point, he responds with the formal announcement of Tregarthen’s impending execution.

The order is to be carried out within three days, enough time for Kelly to travel to headquarters - and return with a firing squad. But first he must interrogate the captured Tans. While Kelly is thus occupied, Molly manages to convince the love of her life to take her with him. Johnny only agrees to the plan on the promise that Michael will convince Kelly to rescind the execution. If Johnny and Molly can make their way to Belfast on the early morning goods train, and from there to England, all will be well. Michael knows how to distract the guards, and Molly can bribe the train driver to let Johnny jump aboard. Three loud whistles will give the all-clear. With hopes of future happiness rekindled, Molly and Johnny each rush off to their respective tasks, and Michael is left alone with three empty glasses that he cannot see – a detail that does not escape Kelly’s notice as he re-joins Michael to formally accept his plea for clemency. Which he says he will duly submit to "the general," but in his estimation the chances of success are slim. "For God's sake, don't build up hope," he tells Michael before agonizing – to himself – over how to soften the blow for Michael: by bringing the execution forward and keeping it secret, he is certain he can spare Michael the pain and the guilt of having to witness the event.

Act 3

In the pre-dawn hours of the following day, Michael and Johnny are wide awake and waiting for the sentries to change and the train to whistle. Thinking the house empty and their enemies far away, they pass the time in a dreamlike state of high anxiety, reciting heroic poems and melancholy songs in whispering voices, so as not to miss the stroke of six to mark the end of their nightmare and the beginning of a new life – only to see Kelly standing in the door, with orders for Johnny to be executed at dawn, 24 hours earlier than they were told originally. Michael's world is falling apart, he pleads with Kelly, he begs him to show mercy, but an almost equally distressed Kelly reminds him that "I have never promised you hope." Johnny declines the comfort of a priest or minister and is led away to meet his fate offstage while, also offstage, Molly will be waiting in vain for the love of her life to board a train that will never arrive.

Left on stage for their final confrontation are Michael and his Nemesis, both knowing full well that nothing they can do or say will change what Kelly might term the preordained outcome of their efforts. To Michael's accusation of "trickery" (by which he means Kelly's surprise return before the agreed time), Kelly offers no subterfuge, no defence, and no evasion. Instead, he says, Michael’s agony is self-inflicted: it was, in fact, his own stubborn insistence on hoping against hope that has now led to anguish and pain. The only way for Michael to end all suffering, Kelly explains, is to give up hope. Unless he manages to see past the private pain of the moment and becomes a distant observer, Michael will forever be "tortured by hope."

Here Kelly is borrowing from the Conte Cruel tradition made famous by Edgar Allan Poe but named after a collection of short stories by the French symbolist writer Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam. A useful definition of the genre is that it concerns "any story whose conclusion exploits the cruel aspects of the irony of fate." Not only does Kelly borrow the concept, and the title from Villiers' tale, The Torture of Hope, he even recounts the plot to underline his point:a hapless victim of the Inquisition escapes his prison cell only to stumble into the arms of the Chief Inquisitor. The lesson for Michael is that, like the victim, he keeps on hoping for release only to suffer defeat over and over again. There are no similarities, however, between himself and the sadistic Inquisitor, Kelly says: his mission is to ease Michael'ssuffering, not to prolong it.

We are given no reason to doubt Kelly’s sincerity, but neither can we reconcile the apparent contradiction between his declared intention and putting Michael’s best friend before a firing squad. If Kelly wants to end all suffering, as he says, surely, a good start would be to save Captain Tregarthen’s life? It is the argument that Michael himself is trying to make, by reminding Kelly of his god-like powers. Michael’s understanding of those powers differs fundamentally from Kelly’s own. Michael’s life-affirming principle of hope and Kelly’s seductive all-consuming fatalism are the two opposing philosophies that take centre stage in the final scene – while John Tregarthen dies a largely symbolic death offstage.

Johnny’s death is symbolic in that it is not the tragedy at the heart of the play. Michael O’Riordon is the conventional male protagonist whose existential crisis we are witnessing; Michael is unable to prevent the execution of his best friend; and to make that very point, his best friend must die. Michael’s blindness contributes to this failure in the course of the play but read as a metaphor it turns Michael into “one of us.” His blindness leaves him vulnerable to attack and it echoes our own sense of powerlessness in the face of an overwhelmingly hostile universe. The reverse, however, is also true: being blind, and being a poet, puts Michael in the illustrious company of the Blind Bard, an archetype of Western literature since at least the (mythical) time of Homer: the blind singer/seer whose “inner vision” surpasses that of sighted humanity. His Irish equivalent – and explicit model for Michael - is the (dwarf) Harper of Finn, whose iron-stringed instrument has the power to move its audience to tears. Michael O’Riordon is both vulnerable and endowed with the superpower of emotional insight – fundamentally human qualities that Kelly admires in Michael, and which he admits he does not possess.

Kelly is an abstract concept in human form; even while he is evidently the cause of human suffering, in his denial he appears to be channelling the sadistic Inquisitor. The apparent contradiction is of our own making, though: Kelly is Cruel Fate personified. He represents that which we like to imagine as the source of all our woes - the betrayals, the injustices, the disappointments which inevitably end in what we define as tragedy and what to the rest of the universe, that hostile universe, is of no consequence whatsoever. If we substitute “hostile” with “indifferent,” then Kelly becomes the antithesis to Michael’s humanity – his indifference is as inhuman as the infinite, indifferent universe. Conversely, Michael is not concerned with an infinite universe; his frame of reference is on a human scale, and very finite. Finite. When Kelly challenges Michael to take his place and adopt his abstract, God-like perspective on life, death, and the universe, Michael does reject the responsibility – but also the indifference required for the position. If the promise of a pain-free existence did not convince Michael to abandon hope, Kelly's failure to shame him into admitting defeat is a testament, at the very least, to human perseverance: we will forever be prolonging the agony to delay the inevitable. (1/4)

#Patrick McGoohan#Patrick Macnee#Katharine Blake#Douglas Campbell#played the four characters in#The Iron Harp#on Canadian TV in 1959#the plan was to explain EVERYTHING in one brilliant post#well the good news is there will be four posts now wahoo#but I'm already posting out of order because I can't decide on the illustration to go with the historical background#as for the play itself#if you have made it this far and you still care#whether the characters are consistent with the general message the author is trying to convey#your powers of perseverance are truly heroic#the problem I think is that the story does not always align with the metaphor#which I still maintain is the human condition#we cannot ever beat death but we carry on regardless#is it just me or does that cryptic cry from#Free for All#obey me and be free#sound like something the evil Inquisitor or Sean Kelly would say#For Fleetstreetpauline#miss you always

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I don't know if you still check this inbox but your blog has the best Danger Man screenshots I have ever seen. Would you mind telling me where you got the high-res screenshots from? I'm starting to think you remastered the film copy yourself :)

Ahhhh, thanks for your message - I am still working on new posts but I was shocked the other day to realize that it's been over a year since the last one...real life is an abominable nuisance. As for the screen shots - I wish I had access to those masters! Sadly, with the demise of Network, there is no hope now we will ever see a Bluray release for the series. Only three Danger Man episodes got the HD Bluray treatment from Network: View from the Villa, Colony Three, and No Marks for Servility. All other screenshots on my Tumblr are from the DVDs. xxx

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The events of 6 December 1890 were neither preordained nor were they premeditated. Nothing that transpired on the day was inevitable or irreversible: participants chose to stay in character, and to act out their roles in what would eventually be described by biographers and historians as the Parnell Tragedy (Jules Abels, 1966).

Everyone at the time would have been aware of the historical significance of their actions, if not the long-term consequences - excluding of course, the one female member of the cast who could not possibly have known what she was doing. By dint of this congenital deficiency she would also quite naturally be blamed for causing "Ireland's misfortune." Simple and satisfying in terms of its mass market appeal, feminine impulsivity does little to explain the supposedly rational decisions taken by the men around her in the name of patriotism and political expediency - which far from producing an amenable solution served only to exacerbate the crisis. Whereas the exact circumstances and full cast of characters have faded over time the larger-than-life figure of Charles Stewart Parnell still towers over the events of 6 December 1890 as the one man who could have had it all - and lost it all.

Sixty-four years later, the Fall of Parnell inspired an episode of the BBC's "experimental" television series You Are There which set out to present the known historical facts, faithfully, but with an added dimension unique to the new medium: actors would impersonate the key personnel as in a conventional re-enactment. While going about their "business," however, they would be interviewed by modern television reporters. The curious anachronism underlined the artificiality of the concept; it meant the programme was deliberately drawing attention to itself which would have been an unwanted distraction, for You Are There it was the defining feature. Neither the programme nor its - fictitious - journalists were interested in the exploration of alternative histories or in-depth character studies: the point was to demonstrate the possibilities of "live" television, ironically, in a simulated setting. Fact and fiction are trading places as the reality of 1890 becomes the subject of a 1950s fantasy, and the medium of the future interrogates the evidence of the past. For the actors it would have been a challenge to navigate between imaginative portrayal of a fully formed human being and the faithful rendition of the intrinsically incomplete historical record.

The historical record states that Charles Stewart Parnell was born in 1846. The son of a Protestant Irish landowner and an American mother was not naturally predestined to champion the cause of destitute Catholic tenant farmers; indeed, nothing in his early life pointed to any such leanings. As an aristocratic country gentleman he had nothing to fear and everything to gain from the firm imperial rule exerted by the British Crown over the Island of Ireland.

And yet it was Parnell, the English-educated man of pedigree, who emerged as the voice of the starving rural population. Having decided to enter politics for reasons that are still unclear, he found his calling as the Westminster MP for County Meath not in the defence of privilege but in the vocal support - initially for land reform and then increasingly for Irish nationalism ("Home Rule"). Over the next five years Parnell gained a reputation and a following as a fiery orator back in Ireland and a force to be reckoned with in the House of Commons, where is name became synonymous with the new parliamentary tactic of "obstructionism." If the English politicians could not be moved to act in Ireland's interest Parnell vowed to meddle in English affairs. And meddle - or obstruct - he did. After a century of inaction and neglect, the Irish Question seemed relevant again, if only because its proponents made it impossible for English laws to be passed. Parnell seemed to thrive on his tactical manoeuvring which he was prepared to carry to painful extremes, on multiple occasions – including arrest and imprisonment, at the risk of damaging his already fragile state of health.

By 1880 Parnell controlled both the radical grassroots movement in Ireland and the parliamentary representation of Irish interests in London. The position made him a frequent dinner guest in the homes of friends and allies, where on several occasions he also enjoyed the hospitality of Mrs Katharine O'Shea, the English wife of a fellow Irish MP, who was sympathetic not only to the cause but to the man who personified the struggle. Mrs O’Shea had a discreet arrangement with her husband, Captain William “Willie” O’Shea, the Member for County Clare and Galway: their marriage would exist on paper only for the benefit of Willie’s career; while he conducted his business in London she would reside at their official family residence and entertain important visitors. Parnell would often stay as a guest of the family - to recuperate after gruelling campaigns in Ireland, was the official explanation given.

For the next ten years the couple conducted an illicit affair that produced four children and saw the singled-minded saboteur of the political system lead a double life away from Parliament and in the company of Katharine O’Shea. The relationship was not as one might assume a tempestuous whirlwind romance but a curiously claustrophobic still-life of Victorian domesticity - an alternate, self-contained reality where Parnell and his "Queenie" could act out their fantasy of living simply as husband and wife. Their apparent longing for simplicity may also help to explain the ease with which they expected to lead two entirely separate and parallel lives, apparently unaware of or unwilling to acknowledge the inherent paradox and inevitable complication.

In the political arena Parnell was for most of the 1880s an extremely effective manipulator of moods and opinions, always weighing and adjusting the demands of Irish nationalists against the calls for the use of force from the British press, the public, and its politicians. Anyone looking for a core belief or deeply held conviction would have been disappointed by the vagueness of Parnell's own stated aims - which he used to great advantage because it allowed him to gain the confidence of the British side and the respect of his own following. As a small but significant minority, the Irish (or Home Rule) Party under Parnell's skilful machinations was able to make demands in return for the votes it lent to either one of the two dominant forces in 19th century British politics: the Tory (Conservative) Party or the slightly more reform-oriented Liberal Party.

Parnell’s elusiveness became his trademark: the less he said in public, the fewer appearances he made in Parliament, the taller he grew in stature. In 1887 he was accused of having endorsed the murders of two British politicians in Dublin. When the alleged endorsement turned out to be a forgery two years later, the popular reaction was one of relief and renewed admiration for the noble freedom fighter who had been so horribly maligned. By 1889, it seemed as if nothing could go wrong for Charles Stewart Parnell.

Home Rule seemed within reach when, in May of 1889, Katharine O'Shea learned of the death of a wealthy aunt whose fortune she was to inherit. The additional funds would have been a welcome boost to Katharine's finances had it not been for her husband's unexpected interference. Captain William “Willie” O’Shea chose this moment to strike, possibly to exact revenge, more likely to improve his own pecuniary situation. And thus, Captain O'Shea went ahead and contested the will, citing his wife’s infidelity, and his intention to divorce her. Surprised but hardly alarmed, the lovers welcomed what they thought would be an opportunity for them to make their relationship official, the sooner the better.

From the very beginning their affair had been an open secret in political circles, but the Captain’s announcement put the fact of their adultery in the public domain. With their case not due in court for at least another twelve months (i.e. late 1890), Katharine and Parnell were powerless to stop the scandal from spreading, and their silence on the matter allowed grievances to fester. No public statement was ever published, nor did the couple make any public gesture of remorse. They did launch a half-hearted and unsuccessful counterclaim not to deny the adultery but to accuse Captain O’Shea of adultery as well, presumably to shame the Captain into withdrawing his allegation.

For an entire year the unresolved state of their private affairs overshadowed Parnell’s political battle; it affected his health and continued to corrode confidence among his allies in parliament and at home but most significantly among the ranks of the Liberal Party led by Prime Minister William Gladstone. Ironically, and with tragic consequences for Katharine and Parnell, the earliest and most vociferous condemnations came not from the Catholic Church (both Parnell and Katharine were Protestants) but from the other “Nonconformist” denominations outside the established Church of England, which was traditionally a preserve of the Tory (Conservative) Party. An influential group among the Nonconformists were Methodists, whose large working and middle-class following had found in Gladstone’s Liberal Party their political home.

When the divorce eventually came through in November 1890 (decree nisi), Parnell was branded a “convicted adulterer” but also won the legal right to marry Katharine after completion of the obligatory six-month waiting period (decree absolute). The salacious - and uncontested – testimony offered in the course of the trial was, however, fresh on the minds of his party colleagues who were meeting to decide on his future as party leader a mere fortnight after the court’s decision. Gladstone had already warned Irish MPs of the danger to their alliance, the implication being that the Liberal Party would lose the support of its Nonconformist base if it continued to cooperate with a “convicted adulterer.” The message was clear: Irish MPs had no hope of winning Home Rule with Parnell as their leader. They needed the good will and legislative might of a strong Liberal government - and Liberal voters had strong ideas about marriage and adultery. Gladstone did, in effect, issue an ultimatum to Irish parliamentarians: lose your leader or lose Ireland.

Party activists in Ireland meanwhile re-elected Parnell as leader of the Home Rule Party before news of the ultimatum reached their shores, creating an awkward situation which allowed Parnell to claim he had the backing of the party rank and file, while Gladstone faced the beginnings of a split in his own party over the very issue of Irish Home Rule.

Parnell promptly refused to stand down, declaring instead that he considered the matter of Mrs O’Shea’s divorce closed and that, far from being a friend of Ireland, Gladstone had betrayed their cause. Whether or not the accusation was based in fact [substance] hardly mattered in the greater scheme of things. It was Parnell's word against that of the Prime Minister, and a decision had to be made: should the Irish Home Rule Party defy Gladstone and keep Parnell as their charismatic leader, or should the convicted adulterer be deposed in return for English concessions?

On 6 December 1890, after seemingly endless negotiations, Irish parliamentarians convened another marathon session to break the deadlock without destroying the party, its leader, or their country. Obstacles proved insurmountable as Parnell himself chaired the meeting and overruled any motion calling for a vote. Members present at the meeting noted his increasingly autocratic behaviour with concern and were alarmed by the apparent disintegration of his mental and physical identity. What they were witnessing may have been, on one level, the self-evisceration of a disgraced politician, but the concrete struggle of the individual to control his own destiny, and the narrative about it, had gained additional layers of meaning that transcend literal explanations for Parnell's fate.

The extent to which he did control the mythology of his downfall as well as his subsequent (and posthumous) apotheosis is a fascinating subject for debate: was he drawing attention to the opposing forces behind his identity or trying to deflect attention away from his failure to reconcile the two when he claimed that Gladstone and the Liberals were the true enemies of the rightful Irish claim to self-determination? No longer was the crisis a moral dilemma but a question of national pride. The private transgression becomes an affair of state - no longer is it a moral dilemma but a question of national pride: if it was up to the English to dictate who is to be their leader, then Gladstone truly was the master of the Irish Party.

Parnell's rhetorical masterstroke elevated his imminent ouster as party leader to an affront of international proportions by blurring the very boundaries he had otherwise hoped to maintain between the private man and his public persona. It also drew an instant reaction from the assembled party colleagues. "Who is to be the mistress of the party?” put paid to Parnell's noble-minded aspirations and reminded those present once again of the sordid scandal and the root cause of their troubles. Unable to vote the party leader out of office, 44 of his fellow members stood up and left the room, 26 remained with Parnell. It is this moment You Are There chose to dramatize, for the sheer symbolism of the scene: the leader without majority, his party crippled for decades to come. The Liberal Prime Minister ruling unencumbered.

Parnell's story, the story of Ireland's struggle, could have ended here. Or it could have ended differently. If each of the protagonists had chosen a different course of action. Parnell, for his part, chose to fulfil what he must have thought of as his destiny: within hours of the party meeting that left him - it must be remembered - still nominally undefeated, he embarked on a tour of Ireland to speak at rallies and unite the crowds behind the candidates he chose to stand in by-elections. Any hopes of regaining the momentum lost in London were slim at best; the winter weather and Parnell's failing health reduced the schedule and, compounded by his ever more radical oratory, crowds became more difficult to control, and enthusiasm for the struggle was waning. But just as the chances of a concrete, real-life settlement were growing increasingly remote, the idea of the struggle captured the imagination of contemporary and subsequent generations, and Parnell became its idealized figurehead - not without considerable work from Parnell himself, who cultivated an air of steely nerves, superhuman strength, and emotional detachment in public while being fiercely protective of his privacy. The polar opposites that defined his existence, through their very incompatibility, presented an impossible conundrum: unable to reconcile the two, incapable of compromise, the Parnell machine was at a crisis point.

Campaigning in Ireland continued throughout the summer but none of the chosen candidates were victorious. Parnell and Katharine finally became a married couple on 25 June 1891, but their life together as husband and wife only lasted a little over three months and ended with Parnell’s death on 6 October 1891. They were both 45 years old at the time.

In poetic terms, Parnell had committed the ultimate sin of the tragic hero: to think of himself as indispensable. In the eyes of his supporters, and presumably his own, Parnell had become the personification of an idea, an idea that without him was thought to be non-viable. Parnell and Irish Home Rule were interchangeable; the means and the end had merged into one. Much like the fatal flaw carried by every tragic hero in the history of human endeavour, Parnell's hubris made him both unique and universal, gave him superhuman powers and made him vulnerable - not in a simple case of crime and punishment but in the pursuit of a noble mission that is ultimately larger than the man who has internalized it as his own.

To paraphrase Hilary Mantel, we tend to fictionalize those who can no longer speak for themselves; in Parnell's case there is perhaps a greater need than with many of his peers to interpret where we cannot explain, and to speculate were we cannot know.

Indeed, so strong was the sense even among contemporaries of a catastrophic derailment of their hopes and dreams, and so great the loss of confidence in the political process, it gave rise to an entire subgenre of historical fantasies indulging in mostly wishful thinking: what if Parnell's campaign had been successful and he had lived to see an independent Ireland? What if there had never been a scandal? What if we could turn the clock back far enough to prevent all bad things from happening? This being a male-centric scenario we easily move on to imagining the hero going about his business without "distractions," and what might have been if Parnell and Katharine O'Shea had never met. The further the fantasy travels back in time, however, the more it will be about erasure of the past rather than an extension of existing timelines. As a work of fiction, it may well be a legitimate subject for philosophical or even psychological enquiry that can provide a temporary reprieve from the struggle. It can never be the solution. [Part 2 of 2]

#Patrick McGoohan#Helen Shingler#were 26 and 35 years old respectively#when they portrayed Charles Stewart Parnell and Katharine O'Shea live on BBC TV#impossible casting by today's standards but in 1954#leading men were expected to cover a much wider age range#fortunately the BBC secured for the part#of the enigmatic giant of Irish nationalism#an actor whose heritage and disposition were an uncanny match#having played much older men on stage before as was indeed the practice in#repertory theatre and the tradition carried over into early television#interestingly the young talent that the new medium attracted in its experimental phase#later launched a televisual experiment of his very own in the pursuit of something#as elusive maybe as the source of Parnell's political ambition#whether it is life imitating art or patterns emerging in hindsight#we will interpret and fictionalize#compare and analyse to satisfy our own obsessions#because that is what this is really#who in their right mind would see shades of Parnell in Col Rumford#or the myth behind the man#for fleetstreetpauline always

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

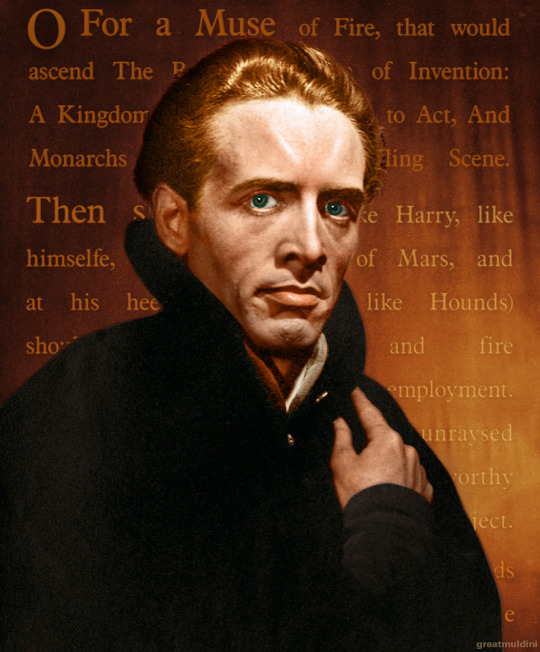

Any household equipped to receive the television service of the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1954 would almost certainly have done so on a “table-top” set not unlike the moderately priced and now iconic “TV-22,” which featured a circular 9-inch Mullard “television picture tube” capable of displaying the 405 lines its electron beam had to travel to draw the “high definition” images coming from London’s Alexandra Palace or the Birmingham transmitter in Sutton Coldfield. First manufactured in 1950 by Bush Radio, then under the umbrella of the Rank Corporation, the Bakelite-clad receiver came with connections for a dipole aerial and AC mains power, and no option at all to change the channel. What today would be considered a serious limitation was in fact a pragmatic decision as long as the country's airwaves remained limited to a single channel. (The set would have been ready for three additional channels which were proposed but never implemented.)

Growing audiences and an expanding schedule forced the new medium to create new content if it intended to fulfil its mission as a public broadcaster to “inform, educate, and entertain.” While the BBC's radio service had famously been on the air since 1922 and earned its merits during the war, television remained for a long time an experimental technology of questionable utility. Early programming therefore relied heavily on the spoken word and the conventions of live theatre, including the singular, and ephemeral, nature of each performance: very little was pre-recorded (on film), and once a programme was broadcast it ceased to exist. Much of the BBC's live programming and even material recorded on tape is now lost; what we do have from the era before and just after the introduction of magnetic tape in 1956 was routinely filmed off the television screen in a process known as kinescoping. Preservation of its output did not rank among the BBC's priorities; recording everything on film would have required vast resources dwarfing the convenience of "canned" content: repeat showings on the BBC often meant repeat performances – bringing the original cast and crew back to the studio was, after all, a well-rehearsed operation and more efficient than any existing technology. Similar traditional arrangements continued well beyond the arrival of effective technical solutions.

The lack of definition, in every sense, at first prevented the new medium from being recognized as such not only by those who worked in it but also the sceptical consumers into whose living rooms the images would be beamed. The privacy of the viewing experience would prove decisive: like its theatrical rival, television was visual, and it was live. With radio it shared the spontaneity of the live broadcast and a large audience that would not need to come together in a single room. Film could offer none of the above, certainly not in combination, but where television (and radio) opted for intimacy on the small screen, film went big and promoted the communal experience – a very basic, fundamental division which remained in place for more than half a century and is only now being challenged by the most recent innovations in streaming and subscription services.

In 1954 the BBC, as the sole operator of the new technology in the United Kingdom, looked to other pioneers abroad for suitable formats with which to fill their expanding schedules. In the United States, commercial television was in full swing by the early 1950s, with major broadcasters such as NBC and CBS competing for viewers and, more importantly, advertising partners – sponsors in the terminology of the scheme developed for radio that had businesses pay for the right to name an entire programme (today's wealth of "archival" recordings from the era is a direct result of the legal requirement to provide proof to the customers that their money was well-spent). Here, too, tried and tested radio content was being adapted for television and, in the process, began to take on hybrid features. One promising concept on the CBS network that appealed to the BBC decision makers was a former radio show turned televisual experiment: You Are There fused (fictitious) contemporary radio reportage with historical re-enactments – easily done on radio but more challenging – and more rewarding – as a live spectacle for audiences to see. Not quite ready, in technical terms, to rival the offerings of the film industry but arguably an alternative to a night out at the theatre, the "night in" promised to become an event in its own right.

You Are There set out to transport the viewer back in time and to bring them face to face with historical figures, who are moreover prepared to pause and be interviewed by modern-day (all-male, often real-life) TV news correspondents. The deliberate anachronism of the programme, examining a fictionalized version of history with the most modern tools available and presenting it to the viewer in the privacy of his own living room was the message and the medium rolled into one: the historical subject under scrutiny was by no means chosen at random or pre-determined by the American creators; licensees around the world dramatized historical events from their own national perspectives. Only seven episodes were produced for the BBC in 1954, none of which exist today. Press reviews and summaries confirm the use of exterior location sequences pre-recorded on film to supplement the live performances in the Alexandra Palace studio, but we can only speculate on the precise treatment of each subject.

The series opened, appropriately, with the Charge of the Light Brigade in the year of its centenary, followed by the trials (and tribulations) of Mary Queen of Scots, Charles I, Captain Dreyfus, and Julius Caesar. Joining this eminent circle were, somewhat less obviously, the instigators of a minor mutiny, as well as a major figure, arguably, of the Anglo-Irish political struggle whose historical – and literary - significance has only grown since 1954. The Fall of Charles Stuart Parnell has inspired generations of writers engaged in the fabrication of alternate histories. The enigma of his personality, and the complex set of circumstances surrounding the events of 1890 continue to be explored in imaginary what if variations. You Are There, by contrast, portrays a moment in time that must contain a myriad of possibilities. [Part 1 of 2]

#Patrick McGoohan#Helen Shingler#mother of Murray Head and Anthony Head amazingly#You Are There#The Fall of Parnell#would have been closer to audiences in 1954#than the TV programme is to us today#incredible to think that some 60 years later#participants would still have been alive#even though key protagonists had dided by 1937#when the first Hollywood romance was crafted#starring Clark Gable and Myrna Loy#Ireland of course continued to struggle right through#the first half of the 20th century and beyond#with the unfinished business of Parnell's now#heroic failure#though the BBCäs perspective may have been more detached and compressed#into a 30-minute lesson about a charismatic leader who did NOT change British history#when the country was experiencing victory and rationing and had not yet reinvented itself#where conformity was indeed the norm and individuality abnormal unless it came off as eccentricity#and modernity as technological advance#which it did in the case of television before morality caught up#within one year commerical television was on the air and the tv set obsolete#if one wanted ITV#and people did#with consequences for all of us#what a waffle so sorry

21 notes

·

View notes

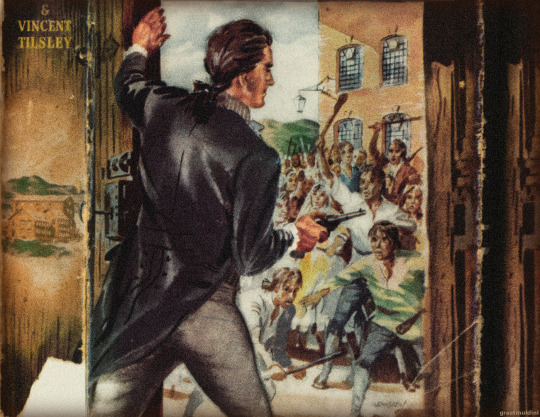

Photo

Anyone visiting the headquarters of the Rank Organization at Pinewood in early January of 1957 would have found the studios operating at peak capacity, with films like High Tide at Noon, The Gypsy and the Gentleman, and Hell Drivers in pre- or post-production and others, like Zarak, on limited or general release. Hundreds of employs would have been toing and froing between soundstages, workshops and dressing rooms, scene docks and exterior lots, working hard to help create, from scratch, the Shakespearean "stuff" our dreams are made of. The irony of the inversion, from Prospero's memento mori to an artificial fantasy sold to millions was perhaps not lost on Rank executives and those who laboured under them.

Far more than the actual product, it was the marketing of the material, the selling of the dream, that proved to be Rank's lasting legacy. The bustling beehive may have impressed on the awe-struck visitor an image Rank were keen to project, of a globe-spanning entertainment empire, but the perfect picture belied a reality of decline underneath the shiny façade at the precise point in time, ironically, when the hiring of artists and other personnel reached its peak. The abundance of available talent, and the urgent need for Rank to advertise its capabilities, allowed the publicity department not only to mount Rank's own promotional strategy but to define the - albeit brief - era of Hollywood gloss in the British film industry.

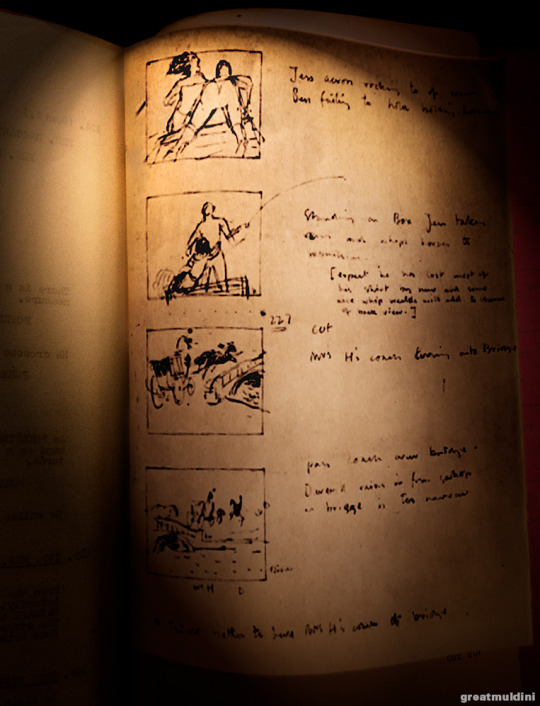

Central to Rank's strategy as a self-styled entertainment empire was the photographic image. In addition to the obvious moving pictures this also comprised still photography, and here it was the easily mass-manufactured 8x10 studio portrait that lent itself in particular to advertising purposes. Reproduced in their hundreds, if not thousands, they would be distributed to advertising agencies, various media operations, sponsoring partners, and Rank-owned cinema chains to beguile potential audiences - so successfully, in fact, that they began to be appreciated in their own right, or as one marketing executive remarked, it was rarely if ever that one saw on the silver screen the "luscious confectionery" beckoning from the display boxes outside.

What made Rank's displays so uniquely irresistible in the eyes of adoring fans and competitors alike was their sheer visual impact: Cornel Lucas joined Rank in 1951, and his position at the time was something of a novelty - and considered an outrageous extravagance in an industry which continued for the most part to rely on hiring theatrical photographers on a film-by-film basis or as needed. Cornel Lucas, by contrast, was employed full time, with his own studio facility, a permanent staff of several electricians, hairdressers, and make-up artists, as well as an endless supply of sitters under varying degrees of duress. The free-lance colleagues of earlier times had been theatrical photographers in the tradition of 18th and 19th century theatrical painters of ornate tableaux, and we see the tradition continue certainly in the theatre but also in "staged" film stills until well into the 1950s and sometimes beyond (e.g. All Night Long, 1961).

Using a large-format Kodak "Model B" view camera, Cornel Lucas embarked on a busy schedule of three to four sessions for each day of the working week, helping the actors develop their on-screen character (experimentation was to an extent encouraged) and, crucially, helping them feel at ease with their Rank-assigned persona. In a view camera, the lens forms an inverted image on a ground-glass screen at the back. The photographer then has to calibrate light, shadow, and general composition to achieve the desired exposure, under a dark hood, in advance and from an upside-down, full-open aperture preview of what will hopefully be the final result. Once he is satisfied, the glass-plate is replaced with an 8x10 sheet of Kodak Super XX Panchromatic black & white film for maximum texture and tonal range. Other than cost and ease of reproduction, it is unclear if any artistic considerations influenced Rank's preference for monochrome photography, or whether it was a conscious decision on the part of the photographer to discard the well-worn utensils and standard techniques of previous decades.

Cornel Lucas has stripped away the scenery, and even most of the actor's own tools, by focusing the camera on his subject's face to the exclusion of nearly everything else. Neither can our eyes stray far from where the lens is pointed. The actor and his audience are locked in an intimate exchange of glances; nevertheless, it is an illusion of intimacy - and a one-way mirror for the actor. The captured character remains behind the fourth wall, in a state of public solitude. Constantin Stanislavski's definition of the actor's task before his audience would seem to suggest there is such a thing as a perfect moment that can be captured in a single photograph when in fact the opposite is the case: developing the character is a gradual process and Cornel Lucas has documented the journey over multiple sessions and in dozens of photographs, each capturing a unique moment along the way.

The exceptional, from Rank's perspective: excessive, abandon with which Cornel Lucas went to work on "G Redman" in January of 1957 has indeed remained something of an outlier in the Organisation's handling of publicity and in the industry as a whole. Against a backdrop of unlikely circumstances (rationing of fuel and paper, dwindling audiences), the sophisticated and, yes, laborious studio session was allowed to flourish for a brief period before it gave way to the more dynamic approach of the 1960s which introduced small-format, hand-held action shots, and new notions of immediacy and authenticity. By 1959, the Rank Organization as a Hollywood-style production company had ceased to exist, and with it disappeared the need - and the demand - for posed portraits. Free-lance still photographers now worked on the set alongside the actors, who could even be entirely oblivious of their presence.

While it lasted, the symbiosis between Rank and Cornel Lucas created an environment in which the photographer had carte blanche to produce as many alluring shots as he could of a (new) Rank hopeful with the full blessing of the company, whose strategy was built on the assumption that the more alluring the promotional photograph the more willing potential audiences would be to buy tickets to see the (far less exciting) film. This dual purpose of promoting the film and the actor at the same time (Rank assets, both) also had the effect of reinforcing the contrast between the two: whereas most of Rank's cinematic output has faded into obscurity, the work of Cornel Lucas continues to fascinate.

#Patrick McGoohan#Hell Drivers#Red#is magnificent Mr G Redman#in all his glory and that is quite literally speaking an actual fact#as there are#dozens of surviving shots testifying to#Rank's promotional profligacy in 1957#and the schizophrenic approach they took to the marketing of their own property#which at that precise moment in time included a promising new acquisition#whose capabilities were as yet uncharted#his depths largely unexplored#and where Rank failed to act on either cue#Cornel Lucas filled the void#with glorious images of#conflict and complexity#the likes of which we would#never see again#Ohhhhh Red

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

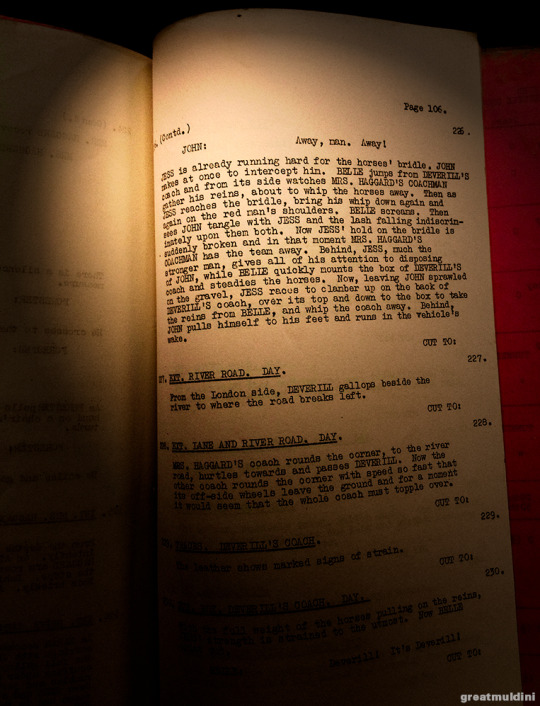

[expect he has lost most of his shirt by now and some nice whip weals will add to charm of back view]

Blacklisted by Senator Joseph McCarthy for alleged "anti-American activities" and unable to work in Hollywood, Joseph Losey along with dozens of like-minded actors, directors, and creative personnel fled to Britain in the 1950s. Since before WWII, the trans-Atlantic relationship between the two entertainment industries had been a complicated one but in the prevailing climate of disintegration and consolidation, the influx of major (and minor) Hollywood talent was warmly welcomed. The Rank Organisation cultivated a reputation for going on indiscriminate spending sprees but invariably found itself having to release its expensive acquisitions for lack of meaningful employment.

Among the post-war Rank recruits, content creators were the exception, and this affected the quality, if not the quantity, of the Organisation's cinematic output. When Joseph Losey finally did receive his first assignment, to direct The Gypsy and the Gentleman, it bore the hallmarks of a case in point: no records have as yet emerged that would explain the somewhat eccentric choice, for the politically left-leaning Losey, of a lavish costume piece about the demise of a weak-willed nobleman at the hands of his ruthless gypsy lover - unless one is inclined to see in the material a parable of Western decadence, as Marxist observers have done.

While a strictly ideological interpretation produces interesting speculative conclusions, perhaps the more productive approach is a purely visual one: dismissive of the subject-matter and unable to shape the material to his liking, Losey never attempts to explain his characters or their motivations. The result is a very deliberate focus on the process of telling the story rather than why it is being told, and Losey turns to the expertise of the painter and art school teacher Richard MacDonald to direct what he would later describe as a study in style. Losey and MacDonald subsequently collaborated on a number of films but it is in the development of The Gypsy and the Gentleman that their idea of "pre-design" begins to emerge.

And concrete shapes are Richard MacDonald's primary concern: long before the cast arrived for initial rehearsals in June of 1957, MacDonald was creating actual three-dimensional spaces (rather than trompe-l'oeil, i.e. painted, theatrical backdrops) for a quasi-authentic Regency environment. Faithfully executed by the Pinewood workshops, the sets delivered exactly what the director had ordered: a static tableau of period décor, unlikely to interfere with the dynamic action of the living, breathing human beings assembled to animate the scenery. Ideally, it would have been assumed, they would somehow combine to form a meaningful whole. The dynamism of the human component and the critical role of capturing the perfect - moving - image is not lost on MacDonald. From the final shooting script of 12 April 1957 he prepared a frame-by-frame storyboard pre-visualizing camera angles, editing suggestions and emendations where the script omits important visual clues.

The final dramatic coach chase in SCENE 226 lacks precisely such clues. It has Jess and Belle racing after the vehicle containing Deverill's sister Sarah - and their last hope of swindling the young woman out of her rightful inheritance. Jess deftly dispatches Sarah's fiancé before catching up to Belle's commandeered coach. The script describes how Jess clings to the back of the coach, then climbs over the top and joins his partner on the box, taking the reins from her. Translating the verbal instructions into "actionable" images, the sketch artist is faced with crucial choices: whose point of view will we be sharing, where are we in relation to the characters, what are the characters doing and how are they doing it?

In MacDonald's concept the camera follows the coach and allows us to watch Jess, from a slightly elevated vantage point and at a medium distance, which frames his figure framed atop the speeding coach. His technique, crouched low on his stomach, and the fact that he is moving with a natural ease and grace suggests he has done this before: Jess knows what he must do to get what he wants. The "savage" man's essential virility (in stark contrast to Deverill's effete decadence) is sketched out by MacDonald in a few sparse pen strokes not of his face but of his obviously well-endowed body in the act of taking control. We do not need, indeed it would be beside the point, to read his face for signs of physical strength and determination, which are required in the situation and which Jess does have in abundance.

MacDonald would have drawn his inspiration from the characterizations of Jess throughout the script, but he goes above and beyond the written word where continuity is less than assured and actions must and will have visible consequences. Following the coach man's ferocious use of the whip against his attacker, MacDonald's instinct is to zoom in on the gory details - with a flair for unflinching hyper-realism only the true aficionado would have appreciated had the sequence been filmed as planned. Unfortunately for the aficionado, in the finished film the coach man no longer wields his whip, and the only drastic imagery we are being exposed to is the crude back projection footage that has taken the place of MacDonald's charming back view proposal. Ultimately, of course, only those images that make the transition from sketchbook to screen will live to tell the tale.

Making those life-and-death decisions is the director's prerogative; his omnipotence however does not extend beyond the telling of the tale: Joseph Losey does not choose his fictional characters, nor does he decide what happens to them. His selection criteria are practical rather than ideological, aesthetic rather than commercial - or they would have been, in an ideal (fictional) world. The bold proposals of his draughtsman may have presented Losey with a variety of stubborn obstacles, but an equally plausible explanation for the use of conventional studio footage in place of the more experimental tracking shot could be post-production objections to the pre-designed perspective. Scenes could have been rewritten and re-enacted at the behest of unhappy Rank executives, to add close-up shots of the actors' bankable faces amid the racing carriages.

Beyond the promise of commercial appeal it is an intriguing question to ponder whether the studio inserts offer valid or even valuable alternatives to the aesthetic aspirations of MacDonald's narrative. In the end, the project proves its own premise: art may exist for art's sake but no such claim has ever been made for style. As a medium in search of its message, Joseph Losey's visual and perhaps visionary experiment remains strangely incomplete, a promise unfulfilled.

#Patrick McGoohan#Melina Mercouri#Lyndon Brook#The Gypsy and the Gentleman#Jess I'm sure knows all there is to know#about unfulfilled promises#being such a virile specimen of the species#the script rather mysteriously is brimming with#references to his manly deeds and demeanour#but we never get close enough to take a sample for ourselves#that said noone gets close to Jess which suits him just fine as he goes#through the film entirely unaffected by anything that happens#Jess is the ultimate embodiment of healthy#unencumbered self-determination#or as we would call it toxic masculinity#although contemporary commentators preferred a different term#virility is such a strange word isn't it#cringe-inducing these days it used to be the defining quality of heroic men#before they were all emasculated by that terrible scurge of modern morality#the permissive society#and that is why heroic Jess is probably still camping out in the woods somewhere#I know he is#Ohhhhh Jess

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The situation is a little more complicated than we had expected.

Colonel Rumford may be in no mood to make a full confession at this stage, but by choosing instead to state an undeniable fact he is also revealing a weakness that even he cannot yet fully articulate. For Cadet Springer, the unexpected complication comes in Rumford��s use of the first person plural: neither a slip of the tongue nor a deliberate misrepresentation, the inclusive we suggests a collective responsibility where in reality no such unity of purpose ever existed.

In the ideal, self-contained world of Rumford’s imagination, Haynes’ untimely departure would have registered as the tragic, if self-inflicted, accident it clearly was. No one would have raised suspicions, no one would have investigated. Any questions of culpability would have been handled under Rumford’s own military jurisdiction. Springer would have been responsible because he would have cleaned the gun. Above all else, the board of trustees would never have heard of Haynes’ plans for radical change - plans that emphatically do not include Lyle C Rumford. You're so used to playing God you figure nothing's going to work without you, quips advertising man William Haynes Jr, who clearly relishes the prospect of firing his old nemesis but will not live to see the day.

The bespoke method of his execution even has an – almost – ironic twist in the element of divine retribution when Haynes is quite literally hoist with his own petard. But Rumford's attention to decorative detail is strictly limited, both by physical and imaginary boundaries designed to protect Rumford’s ideal self-contained world from the depravities of external temptation.

William Haynes Jr epitomizes the depraved inhabitants of a world beyond the pale; his reading of Rumford’s dilemma however is to the point: the decision to shun the outside world and remain aloof in splendid isolation has not only created mental barriers an top of physical ones, it has isolated Rumford from his fellow officers and other members of the Academy. With no one to share his responsibilities or indeed his principles, Rumford’s chosen path is ultimately unsustainable – unless he can find an eleventh-hour ally in whom he can confide and with whom he can share the burdens of his office.

When he tells his reprobate protégé to expect a murder charge, Rumford's intention is not to intimidate Springer but to appeal to his sense of duty and, crucially, his loyalty. Rumford needs Springer to be that good soldier who is willing to endure the hypothetical adversity of a murder trial for the sake of a vision that he hopes is as dear to Springer as it is to him personally: the preservation of his beloved, idealized Academy.

Rumford offers to stand by Springer against the evil intrusions of the outside world (aka Lt Columbo) but he does so in the mistaken belief that he is in control of the situation. and that it will help him to remain in control. While it is true that Springer has no insight into what caused the deadly explosion, he knows it could not have been his doing. The advantage is not immediately obvious to Springer, but it is Rumford’s false sense of superiority that will result in a cascade of unintended consequences.

According to Rumford’s logic, Springer was given a task, and therefore Springer is responsible for its proper execution – a closed circuit that begins and ends with the supreme authority of the commandant to assign duties and discipline infractions. By appealing to the good soldier he still wants to see in Springer, instead of winning the young man’s trust Rumford forces him to choose between being punished for not cleaning the gun and being accused of murder.

Instead of manipulating Springer in his favour, Rumford’s declaration of solidarity has exactly the opposite effect: Springer seeks refuge in the outside world. By being a bad soldier Springer demonstrates his true humanity: as a creature of both worlds, he is contaminated by outside influences and far from perfect, yet he speaks the truth and does so with a clear conscience. Ironically, and fatally for Rumford, it is his own – unattainable - ideal of the good soldier which has been diminished, perhaps most substantially by the one individual who we know is struggling to be that perfect soldier, to create that perfect world for himself and his white roses. Who has already lost the fight even though he has yet to acknowledge the fact.

For FleetstreetPauline

#Patrick McGoohan#Mark Wheeler#Columbo#By Dawn's Early Light#Col Lyle C Rumford#lost his battle against the march of time#forty-seven years ago today#but it is somewhat ironic to note that#the real-life adacemy he headed did not become co-ed until 1996#the proverbial writing was on the wall however in 1974#Rumford's existential crisis magically encapsulates the currents and conflicts#of a society in turmoil over its past present and future direction#Rumford's struggle is compelling because we can watch#the disintegration of an institution#alongside the self-evisceration of an uncannily familiar uncompromising character#who fails to live up to his own idea of perfection#and he knows it#Rumford's performance opposite Springer in this scene is#entirely unedited#it is a masterclass in precision and external control#but it too will not save him from the demons within#ohhhh Lyle

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

As improbable as it may sound to modern audiences, the Rank Organisation emerged in the 1930s from the flour milling business of the Rank family with the self-declared aim of producing wholesome entertainment initially for a domestic market awash with unwholesome American imports.

When best-selling South African writer Joy Packer published her latest, much anticipated, romance novel in the summer of 1957, Rank – looking for spectacular yet wholesome family entertainment – jumped at the opportunity and acquired the rights even before most booksellers had stocked their shelves. A film script was drafted, and by the autumn locations had been explored in preparation for the arrival of cast and crew. To build anticipation at home, a flurry of positive press releases chronicled the travails of the film team while it waited for the weather to improve and hospitalized photographers, continuity girls, and camera operators to be released or replaced.

By Christmas work had all but ground to a halt, and what little was left of the cheerful charade evaporated in January when two of the leading players became abruptly incapacitated in separate but similarly self-inflicted circumstances. With Rank unwilling to abandon the project, and key participants no longer interested in its continuation, February saw frantic attempts to tie up the remaining loose ends.

The long-lost safari party finally returned to London in mid-March of 1958, where their employer put them to work while they still remained the property of Rank. The technical term for Rank actors was contract artist, and for them it meant yet more torturous sessions with the studio photographer and promotional interviews about the making of the film; on a higher plane, the director was assigned to extol the educational benefits of starting a bushfire or harassing a herd of elephants.

The three essays to which Ken Annakin lent his name are perfectly happy to follow up anecdotes about the "local" wildlife with the purely pragmatic decision not to show them being mown down by machine guns because “it would be impracticable to get permission … to film such brutality.” Burning down part of the reserve was deemed more practical instead. When after weeks of bad weather two days of sun caused the undergrowth to become “very dry,” the film makers, being wholly dedicated to their art, proceeded to “pump over 800 gallons of paraffin on the scrub in order to make our flames realistic.”

Realism and authenticity clearly motivated Ken Annakin when he personally dropped a live cobra into the heroic game warden’s Land Rover before said game warden crashes said Land Rover (the exercise took seven heroic attempts, we learn) and is then attacked by not just one but an entire pride of lions. Indeed, so engrossed did the director become in this “very exciting true-life adventure,” the story of how the "poor game warden” who had “just sufficient strength to remember that he had a knife" could easily have filled the allotted 90 minutes in Ken Annakin’s version of the film.

Lions, snakes, and rogue elephants are expertly handled by the eminently capable and eminently eligible young men whose job it is to risk their lives in defence of, yes, the wildlife but more importantly, British interests at the outskirts of the Empire: the Rank Organisation by now viewed itself as a key player of the post-war industrial expansion at home and abroad, eagerly looking to forge partnerships with market leaders in other sectors of the British economy.

Ironically, this is where the question of authenticity in a work of art becomes one of life imitating art, as cast and crew bravely faced down death on more than one occasion in the course of their ordeal. Torrential rain caused the entire film to be shot in authentic locations, but it also forced the editor to come up with a new fairy-tale ending to accommodate for changed realities: an instance of art imitating life’s essential unpredictability?

Once again, the boundaries begin to blur: Nor the Moon by Night stands out perhaps not as the artistic masterpiece Rank never attempted to make but as a milestone of a different kind - marking the passage of an era of film-making that relied on a studio system steeped in the traditions of the theatre, and the artificiality associated with it. The “vertical integration” strategy of the Rank Organisation in the post-war period was coming under pressure from two directions at once, television delivering its product directly into people’s homes, and the growing taste for independent film-making, with its own brand of emotional authenticity-for-its-own-sake, in stark contrast to Ken Annakin's highly selective kind, which serves a clear purpose.

Annakin would have seen no conflict between the message of the film and its making, between art (in the widest sense) and commerce; indeed, Nor the Moon by Night was explicitly designed not only to fill Rank-owned theatres but also to sell other commodities, from South African holidays to British-made off-road vehicles. Implicit in this fantasy is the reassurance that everything will be exactly as advertised. Potential visitors need not fear any change in the status quo. The idyllic picture of life in the South African wilderness is exotic enough to be exciting and static enough to be reassuring.

In one final ironic twist, Annakin’s boastful summary actually highlights the gap between truth and fiction, fantasy and reality, life and art: “It turned out to be the most difficult and trouble-ridden film which I have ever made.” The profundity and prescience of his own words may well have escaped him.

#Patrick McGoohan#Nor the Moon by Night#Andrew Miller#is not amused#clearly#of course he isn't#who would be#you've waited months for some exciting new discovery#and this is what you're getting instead#then again we're hardly strangers#to the high art of#rationalizing the anticlimax#although I'm not sure there is#anything rational about my handling#of the fact that they#recorded actual interviews with the actors#took hundreds or thousands of pictures#and sixty-three years later#there are hardly any traces left of these historical artefacts#yesyesyes it's all terrible propaganda#obtained under duress etc etc#most likely of the excruciatingly cringeworthy kind#but speaking as the serious biographer and cultural historian that I obviously am#the losses to womankind are inestimable#ohhhh Andrew

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

He sometimes stays up all night trying to figure things out. Nothing ever works.

While All Night Long has met with near-universal praise for its musical score featuring some of the best-known Jazz artists of the day, the critical response to other aspects of the production can only be described as less than unanimous. Amid general complaints about the "unbelievable" plot, the "overplaying" of certain parts, and the under-use of available talent, the film’s creative team have been accused of “signposting” their borrowings from Shakespeare, and criticized for not following the “original” closely enough: after the daring depiction of “intermingling” between white and "coloured" characters, the film then withholds the expected interracial “lover’s kiss” and, worst of all, the familiar ending to the familiar story, which is the capital punishment of the lovers for their respective transgressions.

The perception persists to this day, of All Night Long as an ambitious experiment that fails to fulfil its potential - a potential moreover fraught with historical significance had the film been able - or indeed inclined - to present an updated adaptation of Othello, an authentic portrayal of the contemporary Jazz scene, or a comment on race relations in post-war Britain. Each scenario being a monumental task in its own right, any combination would have been well-nigh impossible to tackle. Criticism was concerned with opportunities wasted and expectations frustrated – precisely when it is the protagonist’s fate to remain forever stunted in his growth as a person and a human being, and who is instead condemned to suffer, in perpetuity, the consequences of his own catastrophic failings.

If one character can be said to represent the ultimate waste - of a human life - it is not Rex. It is not Othello. The tragedy unfolding in the course of the night is not the wanton destruction of innocent lives [though the attempt is certainly made], nor will the guilty party receive what would be considered his "just" punishment [though the concept of poetic justice is certainly debatable]. In the absence of a [superficially] satisfying conclusion, the temptation to find fault with the film itself has been irresistible but perhaps the very image of the film’s characters as “puppets whose strings are not jerked by any logical sequence of events” points to a possible flaw in the reviewer's own logic. By assuming that a) the film intends to mimic Shakespeare and b) it does so badly, he is a) demanding that the characters behave more like their Shakespearian ancestors while b) simultaneously complaining that they have no self-awareness.

This basic assumption also has a self-limiting effect as it excludes the possibility of other intentions. What if Othello/Rex was never envisioned as the central character? What if his reunion with Desdemona/Delia was not an outrageous debasement of the Shakespearian tragedy? What if Johnny Cousin actually did behave like Iago in refusing to explain himself, or the film of the dramatic scenario he has scripted, orchestrated, and directed. Indeed, what if the other characters act like puppets because they are remote-controlled, not by Shakespeare but by their modern master of ceremonies, that enigmatic virtuoso, the egregious, the extraordinary Mr Johnny Cousin himself? What if Johnny had decided it was his time to be the “big man,” and to wrestle the script book from his handlers? What if Johnny Cousin had created his own perfect little universe and put himself in charge only to find that his artificial fantasy is as fragile – and as ephemeral - as the chemical high from his last fix. When the music stops and the euphoria has worn off, the flesh-and-blood people, puppets no more, are free to leave the stage. For Johnny, the nightmare never ends.

It is intriguing to imagine Johnny Cousin taking "control" of the film's themes, characters, and spaces, regardless of what the creators' original intentions may have been. Having staged the event to advance his own career, ironically, Johnny finds that the space he has chosen is a closed set, with physical boundaries that reinforce rather than relieve the restlessness, and the futility, of his efforts. A single frame of Johnny captured in a desperate lunge for freedom epitomizes, perhaps like no other, the static nature of his situation, seconds before his impossible dreams are quashed against the solid wooden boards of a massive padlocked door.

#Patrick McGoohan#All Night Long#Johnny Cousin#is trapped inside a character#inside a play inside his head#that much we can tell but there is little else to help us#with his intentions or anyone else's for that matter#are Rex and Delia being deprived of their rightful place#as the tragic victims of racial hatred#is the question of race and of racism#being woefully sidelined to make room for#the white villain's ambitions#the argument has certainly been made but I am not so sure#see above#sooo sorry for the waffle#more meat next time#as it were#ohhhh Johnny

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When the Sheffield Repertory Company, on 18 October 1948, invited local journalists to meet the new talent for the new season, it was not the shy smile of a timid stranger that for the Telegraph photographer epitomized the joyous occasion but the incandescent, albeit no less self-conscious, charisma of the naturally gifted performer - who may have begun his formal training on that very day in 1948 but who, by his own admission, had been acting “since birth.”

Indeed, the formal introduction of the new Assistant Stage Manager came a good seven months after the young prodigyhad been granted permission to study with the Company: his first appearance to that effect in the Minutes of the Executive Committee on 9 March 1948 was followed over the summer of 1948 by small to medium sized roles for which he received full credit but no regular pay. The precarious arrangement was revised when a "striking performance" in The Hasty Heart convinced the Executive Chairman that a “very difficult part” had been “played remarkably well.”

Originally performed on Broadway in January 1945, The Hasty Heart takes place at a British military hospital somewhere in South-East Asia, where six wounded Allied soldiers are recuperating from their war wounds. Each one of them represents his particular corner of the Empire or, in the case of “Yank,” a former colony. Looking after them is the equally archetypal female character, Sister Margaret, whose no-nonsense style of nursing soothes fraying tempers, and her compassionate approach helps to heal not just physical wounds. One patient, however, presents an existential problem: proud and stubborn Scotsman Lachlen McLachlen is terminally ill but has not been told he has very little time left. Margaret falls in love with Lachlen and agrees to marry him despite the looming death sentence. When Lachlen finds out he is furious but can in the end be convinced to accept the inevitable as he learns to accept the heartfelt friendship of his comrades and the unconditional love of his fiancée.

Lachlen’s change of heart is the result of an intervention by the “difficult” character, whose presence is required for the sole purpose of effecting that change. As the catalyst who brings about the final reversal of Lachlan's fortune, Blossom provides the evidence of their shared humanity - ironically by being different from everybody else. When Lachlen, hurt and angry at the perceived betrayal of his friends, and the indignity of his situation, declares his intention to leave the hospital and die alone, it is Blossom who steps forward to offer a parting gift. Blossom - who does not speak a single word of English and therefore would not have been aware of what the others knew - communicates non-verbally the pure, raw, primitive emotion that he alone can express. His affection is pure, untainted by superior knowledge or ulterior motives and allows Lachlen to recalibrate his own highly irrational response.

Blossom is a "difficult" character for the actor, who must convey meaning mostly through mime - and who must perpetuate the racial stereotype of the “silent black warrior” as dictated by the script, the tastes of the time, and stage conventions beyond his control: in New York, the part was played by African-American actor Robert Earl Jones (1910-2006, father of James); the 1946 West End cast featured Nigerian expatriate and star of stage and screen, Orlando Martins (1899-1985), who also took the role in the 1949 film version. The Sheffield Repertory Company, as a permanent ensemble, remained throughout the post-war period a close-knit group of local players whose white working class background would have matched the equally homogenous crowd in the auditorium.

While “exotic” characters and locations were a welcome diversion from the daily grind of the steel mills, true-to-life authenticity would not have been the foremost concern on anyone’s mind. Likewise, any lofty notions of "inhabiting the character" would have been dismissed out of hand in the fast-paced environment of the repertory system with its weekly or, as in Sheffield, bi-weekly change-over. Unlike the commercial long-running ventures on Broadway or Shaftesbury Avenue, regional repertory companies relied above all on the "quick study" and improvisation skills of the actor, favouring versatility over diversity. The need for speed also meant that certain shortcuts were considered legitimate, including the use of Blackface to indicate a character's non-white ethnicity.

The challenge for the actor underneath the generic makeup would have been to preserve the dignity of the individual in his care. The experienced producer, for his part, who elected to trust the most junior member of the Company with that responsibility, would have made his choice fully expecting his protégé to succeed. More than an adequate performance, Geoffrey Ost would have seen the “disciplines of the theatre” brought to life on stage - for the final time by the amateur. With their next production, the Sheffield Playhouse set the scene for a professional debut that could have launched a respectable career for the new Assistant Stage Manager had the fierce young “teaboy” been so inclined.

#Patrick McGoohan#The Hasty Heart#Blossom#is a native of Basutoland a British Crown Colony until 1966 We are expected to suspend our disbelief in any theatrical situation#but a super-human effort would have beenr required to mistake a lanky Irish lad fora bulky Bantu from Southern Africa#Verisimilitude could not have been the strategy#this is where the character's lack of English comes into play#the actor must entirely resort to the use of body language#which suits some actors more than others#the most egregious transgression#of our modern sensibilities however#the one that stretches our disbelief beyond belief#is the liberal application of#blackface#still acceptable for Orson Welles in 1951#controversial for Laurence Olivier in 1965#unsustainable for Black Minstrels on the BBC in 1978#I would like to believe that Blossom could have been#ahead of his time in 1948

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Tinker Horse, or Irish Cob, is a relatively recent breed to be recognized as such: derived from the type of animal favoured by Irish Travellers for pulling their traditional caravans, a “tinker cob” had to be sturdy yet patient, agile yet economical - its compact stature still is a defining feature. It was however not until the middle of the 19th century that the people known as Irish Travellers, or Pavees, began to breed the type specifically as a draught horse. The peak period for the ornately decorated, horse-drawn “vardo” caravan fell between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the horses only becoming fashionable in the late 1990s - long after their original purpose had fallen by the proverbial wayside.