Text

Day 7 - Prepping for concept presentation

My part =

4: Concept story (EMMA)

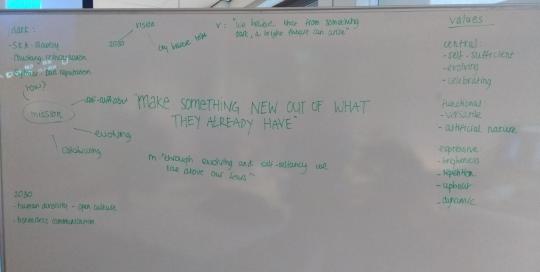

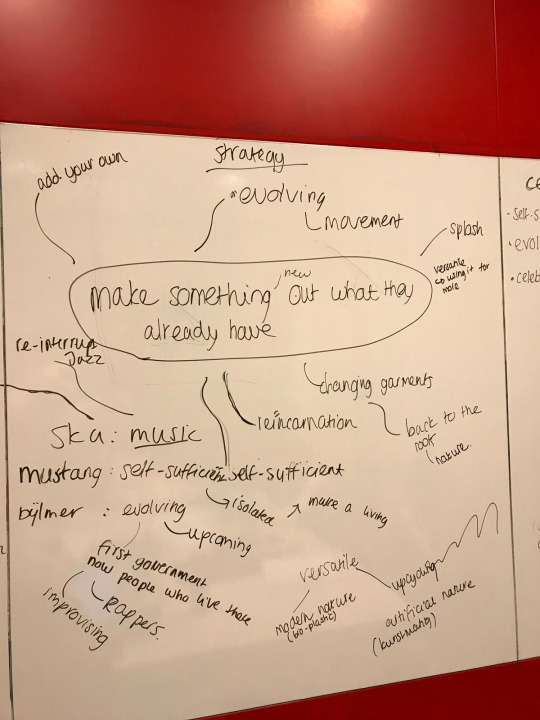

Concept: Making something new out of what you already have

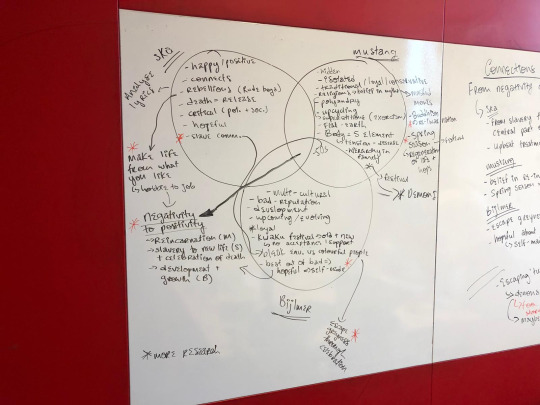

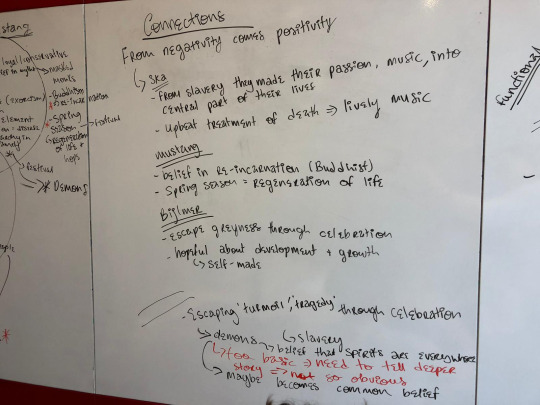

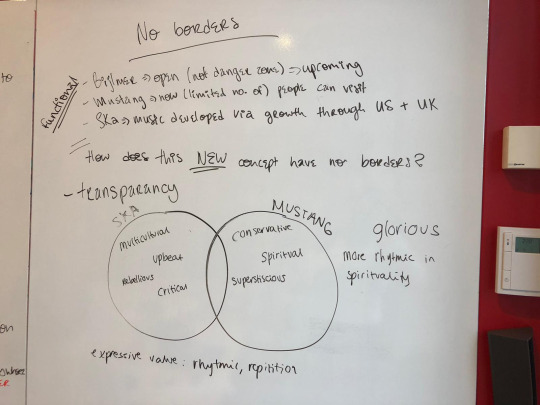

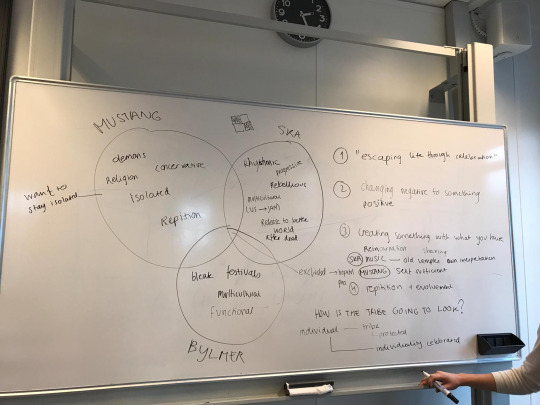

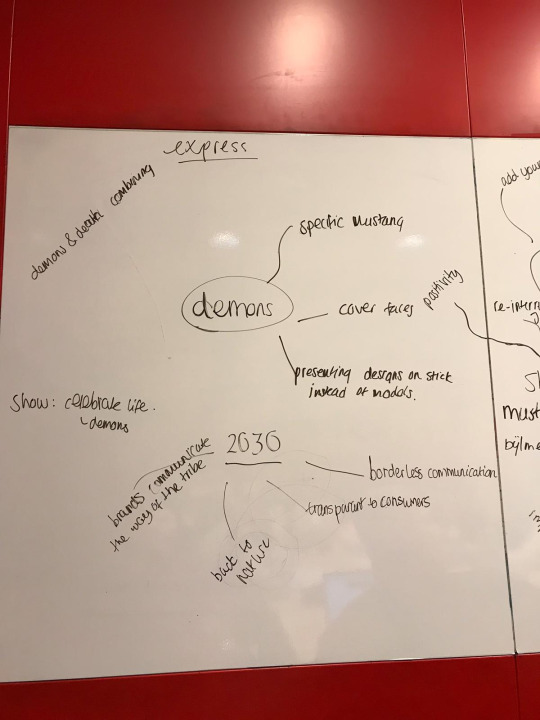

This concept was a product of the connection between our tribe, the Lopa tribe of Mustang, Nepal, our music Ska and the Bijlmer area. We found that each of these treated struggles or negativity with a positive outlook and an aim to make their lives better.

The Lopa tribe believe in reincarnation and, as with their Spring Season festival, they treat re-birth as an opportunity to celebrate not mourn. They are also a self-sufficient community. They do not use outside resources so therefore re-use and up-cycle what they already have into whatever they need.

Ska music arose during the early era of independence of Jamaica from England. It was a time when people who were emerging from slavery and were without possibilities used their passion for music as a release. They translated their hardships into uplifting songs. This music combines elements of Caribbean mento and calypso with American jazz and blues rhythm to create a new sound. Ska music is also played at the Nine Night ceremony which is held when people die. During this ceremony, death is celebrated as a release from earthly cares through upbeat music and dance.

The Bijlmer area, despite a bad reputation, is becoming a space of growth, development and emerging talent. Despite bleak surroundings, they are attempting to create their own vision of what the area should be like through festivals, music and designing their own homes within the area.

As you can see, the theme that joins these three groups is the idea of twisting a negative into a positive and upcycling what they have to work with.

Vision: From darkness a bright future can emerge.

Mission: Through evolving and self-reliance we rise above our fears.

Values:

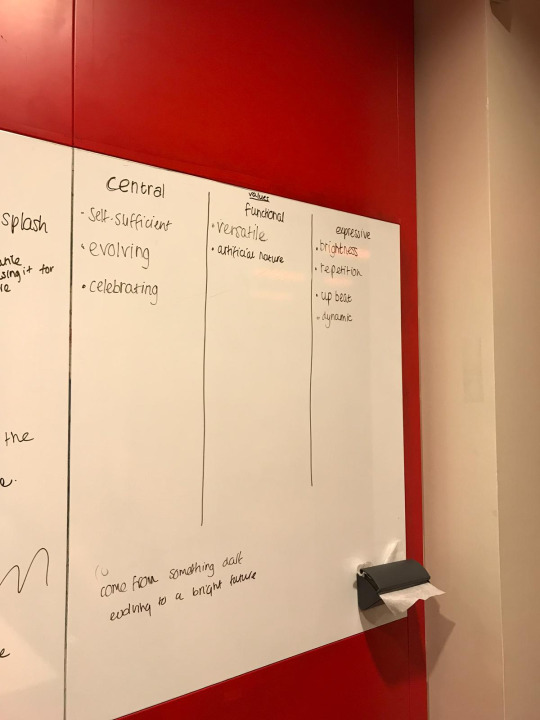

Central -> self-sufficient, evolving, sanguine

We rely on ourselves and our own community to survive and prosper.

We adapt and change to the conditions around us in order to develop.

We bring optimism and joy to situations that may be viewed as negative to outsiders.

Functional -> versatile, ****artificial nature***

We believe that everything should have more than one function and be flexible to our needs at any time.

As resources become more depleted, we see value in using modern technology and inspiration from nature to mimic the materials which are limited in availability or would cause further damage to the environment.

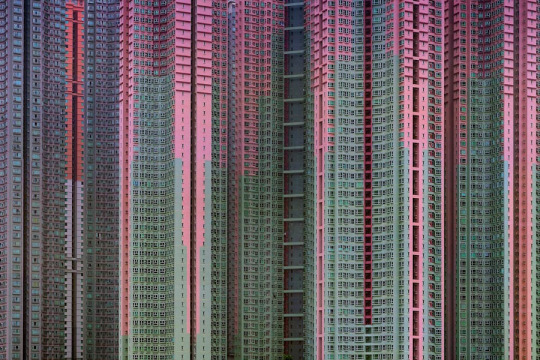

Expressive -> brightness, repetition, upbeat, dynamic

We believe being positive and hopeful is the only way to move forward in life. This is depicted through vibrant colours.

We have repetitive beats in our music and recurring rituals in our daily lives which we also illustrate in the way we dress through layered garments.

Through quick-paced rhythm and cheerful dances we shake off our worries and troubles. We bring this mentality of leaving behind past struggles into our daily lives.

Change, activity, and progress are vital to us. We aim to convey this it in the different facets of our self-expression.

Name ideas (EMMA)

-Evirit (Evolving Spirit)

-Rhynew (Rhythm and Renew)

2030 Bijlmer (EMMA)

We created a mini scenario that appears on the Tumblr. I’m going to discuss the most relevant points now. The goal of our tribe is to continue working towards a brighter future.

Although the rest of the world might still be stick in the world of digitalisation and dependance, this tribe that lives in Bijlmer is self sufficient. Meaning they use what they already have to produce what they need like using renewable energy for example solar and wind and by upcycling. Everything they do, they do together, within their community. Outsourcing and creating more waste is what they stand against. Building human connections is what they stand for. Therefore, everything they produce is friendly to their environment and their people.

0 notes

Text

Day 6 - Researching stand and presentation meeting

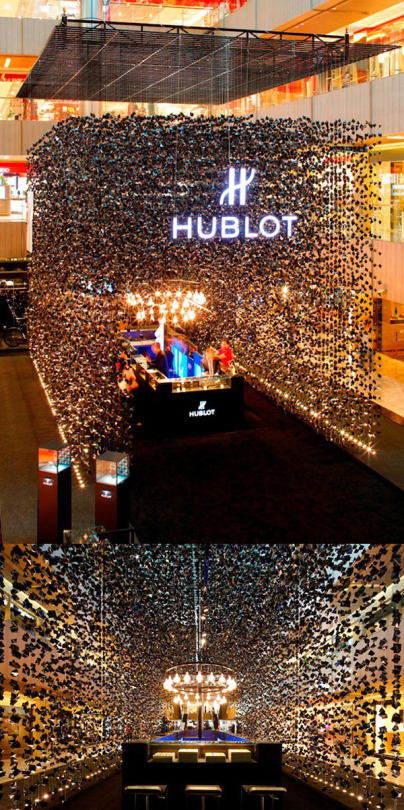

1. Turn Your Products Into Art

2. Upcycled Product Displays

3. Interactivity

https://www.shopify.com/retail/10-unique-visual-merchandising-ideas-you-should-steal

https://fitsmallbusiness.com/trade-show-display-ideas/

https://www.themarketingworks.co/blog/product-display-ideas

http://materialicious.com/2012/10/creative-display-ideas-for-the-home.html

https://www.swirlmarketing.com/blog/retaildetails/tag/mud-pie/

https://boothdesignideas.com/9054-2/

https://www.designretailonline.com/galleries/product-roundups/

Pin by Robin Parker on Display | Pinterest | Display, Store displays and Store

0 notes

Text

Day 5 - Brand book/Concept team meeting

To-Do list:

-think of persona *** ✓

-think of STAGE!!

-logo and name ✓ --- Monday

-concept, idea ✓ ---Sunday

-concept board with visuals ---today ✓

-write out explanations ✓

-summary of links between things for stand, etc.

-what are we going to say for the presentation

-mood board of new tribe -> how it’s going to look now

-mood board/mind-map of Bijlmer for 2030 -> how it’ll look

-visual mood board of concept --- CSM

.

.

.

.

.

.

Concept: Make something new out of what they already have

This concept was a product of the connection between our tribe, the Lopa tribe of Mustang, Nepal, our music Ska and the Bijlmer area. We found that each of these treated struggles or negativity with a positive outlook and an aim to make their lives better.

The Lopa tribe believe in reincarnation and, as with their Spring Season festival, they treat re-birth as an opportunity to celebrate not mourn. They are also a self-sufficient community. They do not use outside resources so therefore re-use and up-cycle what they already have into whatever they need.

Ska music arose during the early era of independence of Jamaica from England. It was a time when people who were emerging from slavery and were without possibilities used their passion for music as a release. They translated their hardships into uplifting songs. Ska music is also played at the Nine Night ceremony which is held when people die. During this ceremony, death is celebrated as a release from earthly cares through upbeat music and dance.

The Bijlmer area, despite a bad reputation, is becoming a space of growth, development and emerging talent. Despite bleak surroundings, they are attempting to create their own vision of what the area should be like through festivals, music and designing their own homes within the area.

As you can see, the theme that joins these three groups is the idea of twisting a negative into a positive and upcycling what they have to work with.

.

.

.

Vision (needs rewording): we believe that from something dark, a bright future can arise

-> In the darkness, we see light.

-> Despite hardships. we see possibilities.*

-> A dark past does not equal a dark future.

-> From darkness a bright future can emerge.*

.

.

.

Mission: Through evolving and self-reliance we rise above our fears.

.

.

.

Values:

Central -> self-sufficient, evolving, celebrating

Functional -> versatile, artificial nature

Expressive -> brightness, repetition, upbeat, dynamic

Explanations - ***QUESTION should I use ‘we’ or ‘they’???

Self-sufficient = We rely on ourselves and our own community to survive and prosper.

Evolving = We adapt and change to the conditions around us in order to develop.

Celebrating = We bring optimism and joy to situations that may be viewed as negative to outsiders.

Versatile = We believe that everything should have more than one function and be flexible to our needs at any time.

Artificial nature = As resources become more depleted, we see value in using modern technology to mimic the materials which are limited in availability or would cause further damage to the environment.

Brightness = We believe being positive and hopeful is the only way to move forward in life. This is depicted through vibrant colours.

Repetition = We have repetitive beats in our music and recurring rituals in our daily lives which we also illustrate in the way we dress.

Upbeat = Through quick-paced rhythm and cheerful dances we shake off our worries and troubles. We bring this mentality of leaving behind past struggles into our daily lives.

Dynamic = Change, activity, and progress are vital to us. We aim to convey this it in the different facets of our self-expression.

.

.

.

Mustang - key things -> red, rocks, grey, black, tones of yellow, neutral coloured flags

Ska - key things -> red, green, yellow, black, white, suits, rebellious

0 notes

Text

Day 4 - Meeting after Research Presentation

Feedback:

-show the connection points don’t just say that there is some

-appreciated music and well- organised structure

-like to see more costume of tribe - not fashion

-more visuals, don’t over-explain one visual, be concise

-research 2030 -ska, mustang, bijlmer

-liked insight into why and story behind development of ska and what was combined and context of tribe - need to know why they behave the way the do --- broaden this - habits, social, cultural aspects

-Most research into bijlmer (good job) ---- Bit too superficial still for tribe and music

-find more about red line --- visualisations of similarities/connections/links so everyone will be on the one page

.

.

.

To-Do list:

-think of brand name and name of target group and send to tumblr team

-need to create one clear concept sentence so everyone can understand it

-send summary of ska to tumblr group

-at end of meeting have check-out ✓

-message own manager rather than Sabrina when need answers ✓

-don’t throw everything in group chat, e.g. small questions ✓

-think about cultural appropriation

-message Juliette to tell her my presentation notes ✓

-how ska and tribe are sustainable and future of it

.

.

.

-need to be really clear about what the tribe is

.

.

.

.

.

.

https://www.ignant.com/2016/05/16/otherwordly-sculptures-revealing-mans-limitations/

https://www.ignant.com/2016/05/06/visualizing-the-invisible-motions-of-kung-fu/

https://synapticstimuli.com/filter/colorful/Desire-to-taste-the-deep

https://butdoesitfloat.com/An-architecture-of-density

https://butdoesitfloat.com/When-light-falls-on-the-retina-of-the-human-eye-it-hits-126-million

http://adultartclub.tumblr.com/post/178676678100/stuff-for-penthouses-ugo-rondinone-black-white

http://adultartclub.tumblr.com/post/176519266275/darrenoorloff-httpwwwdarrenoorloffcom

0 notes

Text

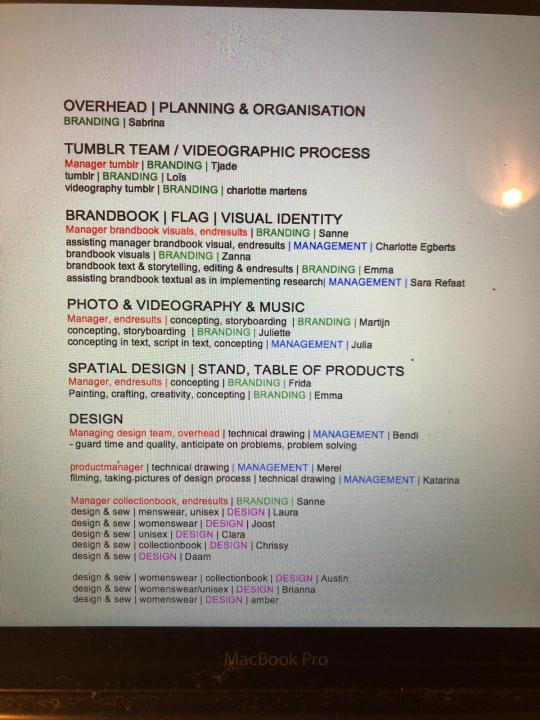

Data 3 - Organisation Meeting

After Sabrina creating this based on the skills and preferences that we emailed her about, we had a meeting to discuss our concerns, ideas and general informing each other. It was organised and everyone's’ voices got heard. Every one seems ready to work and has some interesting ideas.

.

.

.

My to-do list:

-read manual

-come up with concept ideas and a personal vision for “no borders”

-look into innovative but realistic versions of brand books

-look at my old brand book to make sure I know which topics need to cover

-research zero waste

.

.

.

For brand book I need to remember the following headings:

-intro

-vision

-mission

-values=central, expressive, functional

-target group/tribe

-graphic design elements=explanation of colour, logo and typography

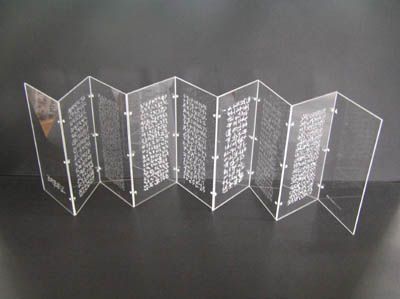

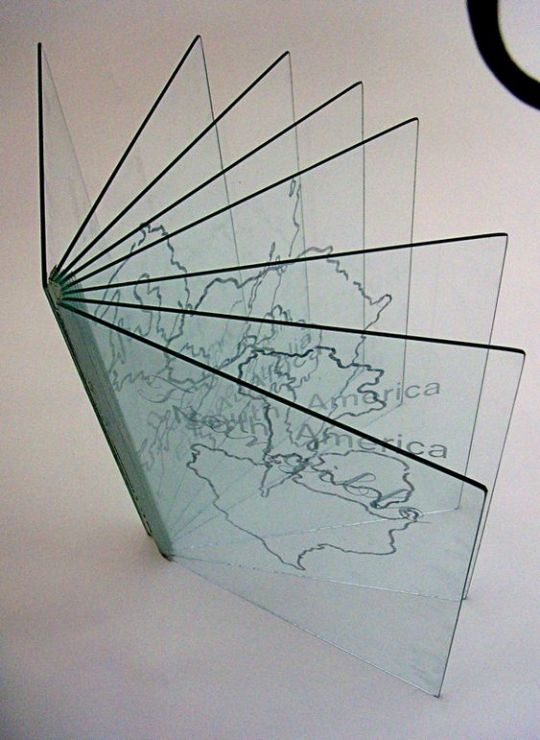

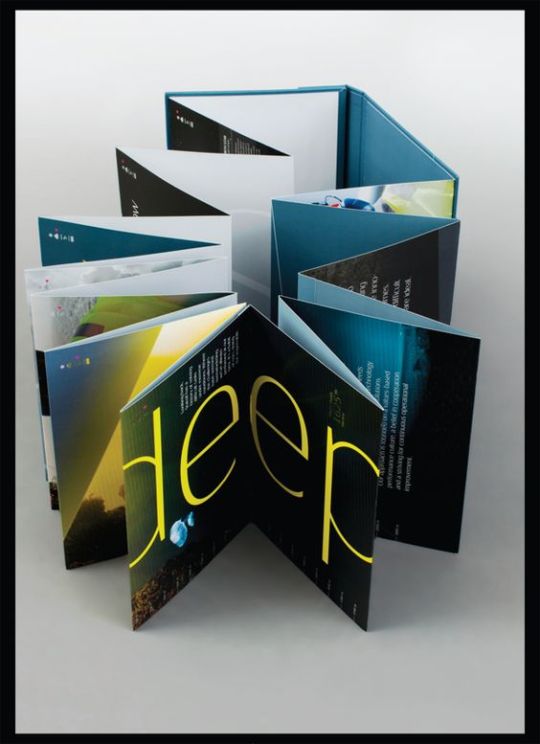

***IDEA!!*** borderless book --> clear pages, pages linked to each other where each page links to the next, e.g. folds out

.

.

.

First associations for concept:

-Ska=Jamaican, 1950s, rebellion, emerging from poverty and exclusion (hope), upbeat, rhythmic, rude boy style (black and white), union

-Mustang Nepal= Nepal, 14th C, preservation, wary of change, red and black colours, sheepskin and linen, forbidden kingdom

-No Borders=gender, race, religion - equality, not promoted just the norm, sharing clothing, not afraid to talk about anything, interracial, blended cultures, reversible clothing (day to night, casual to dressy)

.

.

.

Zero waste research:

1. A globalised fashion industry helps collect unwanted clothing

Unwanted garments tossed into clothing bins have traditionally faced an ignominious future as filler material for insulation or stuffing for toys. But the globalisation of the fashion industry is giving our old clothes a second chance. Lewis Perkins from the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute says that a wide international network of facilities and mills producing clothing for global consumption also means the fashion industry has greater ability to move reclaimed textiles to partners who are able to turn those fibers, yarns and fabrics back into new material. Perkins predicts the growth of schemes such as I:CO (I:Collect), a global Swiss-based firm that collects, sorts and recycles garments. But, he adds, more investment is needed.

2. Designers play an important role in creating a ‘closed loop’ system of production

According to Leigh Mapledoram, programme area manager for textiles and public sector at Wrap: “Design plays a critical role as it has an effect on all process steps, from raw materials to end of life. Designers themselves work in conjunction with other functions from technologists, suppliers and buyers to create the finished garment. It is really about education of all parts of the chain and Wrap research shows that to reduce the impact of clothing, focus should be on extending the active life of clothing.”

3. Will recycling fabrics change the production chain?

Rien Otto, founder and creative director of Dutch aWEARness, believes recycling fabrics will disrupt the current production chain. Instead of working only with a production company, the retailer and the customer, Otto says his company now works with many other players – the yarn maker, the cut, make and trim factory, and the dyeing house. Otto says that, because they all need guidance to recycle fabrics and work in a circular economy, this changes the role of outsourced factories. They have to be transparent about their production processes.

4. We can’t rely on major brands to drive change by themselves

Perkins says the industry needs more collaborations and industry partnerships to create the better materials needed and to recruit the facilities, mills and other producers in the supply chain to innovate. “Of course consumer demand and legislation helps push change, but we need to get the systems in place. Let’s prove the model can work,” he says.

5. Technical elements of fashion recycling remain a challenge

Advertisement

Current mechanical methods can’t deal with blended fibre garments, points out reader CircularC. But as Phil Townsend, sustainable raw materials specialist from M&S, explains, an important part of the innovation process is to work with suppliers to find new ways round some of the technical restrictions. Brands have a major role to play in changing the negative connotations that still exist around recycled materials, he says. It’s time to look at them in a very different way, as desirable and premium instead of tired and unwanted.

6. There will always be textile waste

A zero-waste fashion industry seems unlikely. But Anna Crawley, creative director of the Fara Workshop – a social enterprise designing one-off fashion pieces made from donations – hopes with big companies such as H&M getting involved it will encourage more people to donate their clothing back rather than throwing it in the bin.

Mapledoram believes the answer is to invest in fashion that is timeless and can be adapted and updated to change with the times. He says it offers the biggest opportunity to reduce the environmental impact of clothing. “If the average life of clothes could be extended by just nine months it could reduce carbon, water and waste footprints by 20-30%.”

7. Fast fashion is making it hard to find the best materials

Crawley says we over dye fabrics and clothing, but the quality of recycled garments depends on the kinds of materials you use. Otto describes how many years ago Dutch aWEARness tried to recycle a pair of cotton jeans to a new pair of jeans. The result was a pair of jeans, he says, but it had a very low quality.

He explains how together with its partner in Austria, they developed a special kind of polyester that is fully recyclable. They are conducting research and development on making clothing from miscanthus grass and bacteria as well, as these can be fully recyclable.

8. Developed nations need to lead the way in ethical fashion

“One of the major issues many emerging nations have with our developed world ‘noblesse oblige’ attitude and mandates on environmentalism, renewable energy, and social practices, is that have had the last several 100 years to get it right while we prospered under older and less clean and positive models,” Otto says.

“It’s important we become the model and help the emerging systems by-step less ‘clean’ practices. Some emerging countries are advocating for the right way to produce products and yet resources are limited and the demand for better practices is not always there. It’s a journey for sure.”

9. There will be a time when ‘bring back bins’ are fashionable

Perkins predicts there will be a new generation of consumers who think about where their stuff goes next and that will spark a revolution among retailers. He doesn’t expect to see M&S or H&M providing collection bins in every store; rather, consumer will be given easy access to a location for everyone to send used materials for upcycling. Retailers will still have to compete with online competitors and Perkins believes it could be a win-win scenario – education for consumers and economic drivers for the retailer.

10. We need to change the image of ethical fashion

In order to achieve a circular economy in the textile industry, we need to change the role of the designer and the consumer, says Otto. “Ethical fashion still somehow suffers from a green, dull image, whereas it needs to move to long lasting, highly fashionable [image] that is still quite affordable.” Crawley adds: “Exciting, innovative and fashionable is how I see sustainable fashion.”

11. In the future, sustainable fashion will be the norm

The design of clothing is as important as the ethos behind it. The more desirable the piece of clothing the better, says Crawley, who believes that in the future, ethical and sustainable fashion will be the norm in the fashion world.

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/2015/jan/14/10-things-learned-zero-waste-fashion-industry

What Is Zero Waste?

Zero Waste simply means a product or process that eliminates waste materials. The term can be applied to many different industries, and can even encompass a “way of life”. Within the fashion industry, a zero waste garment is systematically designed to avoid and eliminate wasting materials so that no textiles are disposed of.

Just like the theory behind “circular economy”, the concept of zero waste is one where everything is re-used and nothing is discarded. It is the antithesis of the “build, buy, bury” model – a one way ticket from raw material to factory, to user, then landfill. The circular economy has the potential to completely transform the way in which businesses operate, and resource-intensive industries like fashion are at the heart of the debate.

Why Zero Waste Fashion Design?

Waste is a major contributor to global warming. Solid waste landfills are the single largest man-made source of methane gas in the United States. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that is 23 times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than the most prevalent greenhouse gas—carbon dioxide. For me, Zero Waste is all about addressing waste as a primary root cause of global warming. A zero waste strategy supports all three of the generally accepted goals of sustainability – economic well-being, environmental protection and social well-being.

https://theswatchbook.offsetwarehouse.com/2017/04/26/zero-waste-fashion-design/

When I think about zero-waste fashion, I like to think of it in relation to jigsaw puzzles. We’ve all done jigsaws right? Some of us love them, and some of you reading this will hate them. I loved them as a kid, and I think the puzzle aspect of zero-waste fashion plays off that childhood love of mine. You see, thinking about how to use fabric in a way that isn’t wasteful is like creating your own jigsaw puzzle.

https://www.thecreativecurator.com/zero-waste-fashion/

0 notes

Text

Day 2 - Research articles on Ska

People may not realize this, but ska music originated in Jamaica in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Ska music's influence ranges beyond ska bands. Without ska music, genres like reggae and rocksteady may not have come to be. The ska beat is heavily influenced by American R&B music and has grown into one of the most popular standalone musical genres. It is also one of the most distinct - famous ska bands are rarely confused as being from another genre. The best ska bands are some of the most popular in the world due to the eclectic sound and the diverse instruments used in shaping the music. Ska bands had a surge in popularity in the 1990s with albums like Sell Out (Reel Big Fish) and Super Rad! (The Aquabats) taking over the radio waves. This is the era where some of the best ska bands emerged and haven't let up since.

https://www.ranker.com/list/ska-bands-and-musicians/reference

Genres of music are seldom invented in someone's basement, generally they sort of fade into existence. Such is the case with ska, a genre of Jamaican music which comes from mento and calypso music, combined with American jazz and R&B, which could be heard on Jamaican radio coming from high-powered stations in New Orleans and Miami. Ska became popular in the early 1960s.

The Sound

Ska music was made for dancing. The music is upbeat, quick and exciting. Musically, it can be characterized with a drumbeat on the 2nd and 4th beats (in 4/4 time) and with the guitar hitting the 2nd, 3rd and 4th beats. Traditional ska bands generally featured bass, drums, guitars, keyboards and horns (with sax, trombone and trumpet being most common).

Coxsone Dodd

Clement "Coxsone" Dodd is one of the most important figures in ska history, though he was not a musician. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jamaica was about to receive its independence from Great Britain. Coxsone, a disc jockey, recognized the country's need for national pride and identity, and began recording popular bands in his now-legendary studio, Studio One. These records became wildly popular in Jamaica.

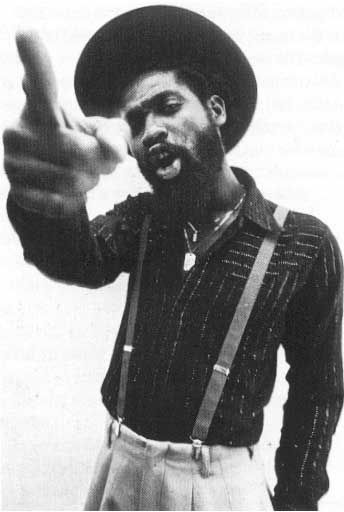

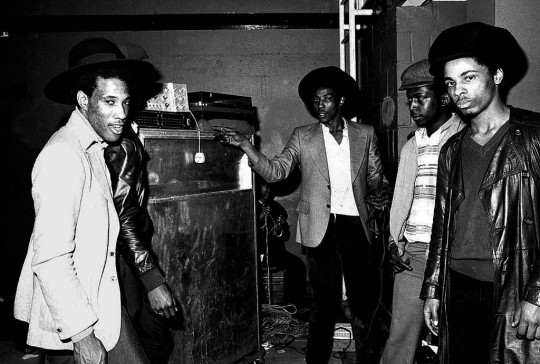

Rude Boys

The "rude boys" were a Jamaican subculture of the 1960s. Rude Boys were generally unemployed, impoverished Jamaican teens who were hired by sound system operators (mobile DJs) to crash each other's street dances. These interactions often led to further violence and the Rude Boys frequently formed feuding gangs. Fashionable clothing for rude boys was American gangster wear. The Rude Boy culture became a huge source for ska lyrics.

Skanking

Skanking is the style of dancing that goes along with ska music. It has remained popular among ska fans since the beginning, and it's a relatively easy dance to do. Basically, the legs do "the running man", bending the knees and running in place to the beat. The arms are bent at the elbows, with hands balled into fists, and punch outward, alternating with the feet (left foot, right hand, etc.).

Traditional Ska Musicians and Bands

Among the artists that made early ska so popular were Desmond Dekker, The Skatalites, Byron Lee & the Dragonaires, The Melodians and Toots & the Maytals. Many ska bands also later played reggae music, which came about later in the 1960s.

Second-Wave Ska or "Two-Tone" Ska

Two-tone (or 2 Tone) ska is the second wave of ska music, created in England in the 1970s. In creating this genre, traditional ska was fused with the (then) brand new style of music known as punk rock. The name "2 Tone" refers to a record label that put out these records. The UK-based bands were often racially mixed, with black and white members.

Two-Tone Ska Musicians and Bands

Popular two-tone ska bands include The Specials, Bad Manners, The Higsons, The Beat and The Bodysnatchers.

Third-Wave Ska

Third-wave Ska refers to American ska bands that were influenced more by two-tone ska than by traditional ska music. These bands range in their sound from nearly traditional ska to mostly punk. In the early to mid-1990s, third-wave ska saw a major growth in popularity, with many bands having several chart-topping hits.

Third-Wave Ska Musicians and Bands

Among the most popular third-wave ska bands are The Toasters, Operation Ivy, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, No Doubt, Reel Big Fish, Fishbone, Less Than Jake, Save Ferris, Sublime and The Aquabats.

https://www.thoughtco.com/ska-music-basics-3552840

Ska, Jamaica’s first indigenous urban pop style.

Pioneered by the operators of powerful mobile discos called sound systems, ska evolved in the late 1950s from an early Jamaican form of rhythm and blues that emulated American rhythm and blues, especially that produced in New Orleans, Louisiana. A new beat emerged that mixed the shuffling rhythm of American pianist Rosco Gordon with Caribbean folk influences, most notably the mambo of Cuba and the mento, a Jamaican dance music that provided the new music’s core rhythm. The boogie-woogie piano vamp characteristic of New Orleans-style rhythm and blues was simulated by a guitar chop on the offbeat and onomatopoeically became known as ska. The beat was made more locomotive by the horns, saxophones, trumpet, trombone, and piano that played the same riff on the offbeat. All the while the drums kept a 4/4 beat with bass drum accents on the second and fourth beats.

Because the history of Jamaican popular music is largely oral, contending claims of authorship were inevitable, but guitarist Ernie Ranglin’s claim that he invented the ska chop is generally regarded as plausible. Singers Derrick Morgan, Prince Buster, Toots Hibbert (of Toots and the Maytals), Justin Hinds, and the Dominoes became stars, but ska was primarily an instrumental music. Jamaica’s independence from British rule in 1962 left the country and ska in a celebratory mood. The music’s dominant exponents were a group of leading studio musicians—Don Drummond, Roland Alphonso, Dizzy Johnny Moore, Tommy McCook, Lester Sterling, Jackie Mittoo, Lloyd Brevette, Jah Jerry, and Lloyd Knibbs—and under McCook’s leadership they became known as the Skatalites in 1963, making several seminal recordings for leading producers and backing many prominent singers, as well as the fledgling Bob Marley and the Wailers. The Skatalites’ most distinctive musical presence was trombonist, composer, and arranger Drummond. A colourful figure who grappled with mental instability (he was institutionalized after murdering his girlfriend and died in confinement), Drummond was the central musician of the era, as essential to the development of ska as Marley was to reggae.

Ska has had several international waves. The first began in the early 1960s and is remembered for “My Boy Lollipop” by Millie Small, a Jamaican singer based in London, and for hits by Prince Buster and by Desmond Dekker and the Aces. In the 1970s ska was a significant influence on British pop culture, and so-called 2-Tone groups (whose name derived from both the suits they wore and their often integrated lineups) such as the Specials, Selector, and Madness brought punk and more pop into ska. Madness’s music crossed the Atlantic Ocean and contributed to the success of ska’s third wave of popularity, in the mid-1980s in the United States, where another British group, General Public, had hits. The music’s fourth wave came in the mid-1990s as American groups such as No Doubt, Sublime, and the Mighty Mighty Bosstones brought ska into the mainstream of pop music, and ska pioneers such as the Skatalites and Derrick Morgan found a new audience.

https://www.britannica.com/art/ska

Ska story: the sound of angry young England

By Stephen Rodrick

Sign up for our newsletters Subscribe

"Forget about punk. Forget about the new Mods marching to the beat of 'My Generation.' In the England of 1980, ska is the word." That's how Rolling Stone critic David Fricke began his March 23, 1980, article on ska, the latest music craze to sweep the U.K. A decade later, the record label most responsible for the ska revolution, 2-Tone Records, has commemorated the tenth anniversary of the ska phenomenon with The 2 Tone Story, a double album that highlights the best of the ska movement and leaves you wondering why the hypnotic music never became the word in America.

The ska of the late 70s and early 80s was a revival of and an elaboration on "rude boy" ska, a craze centered in Jamaica in the first half of the 1960s. Jamaica was in the midst of a cultural renaissance as the island nation achieved its independence from Great Britain in 1962, and its quest for an individual identity is quite evident in ska, a fusion of Jamaica's native folk music, known as Mento, with American R & B, which could be heard from New Orleans at night on the radio. The concoction was heavy on nasty jazz-tinged horns bouncing off a skittish calypso beat. The lyrics were mostly playful, but occasionally touched on the promise of home rule, as in the Skatalites' "Independent Anniversary Ska." By the mid-60s this original ska sound was evolving into the more controlled "rock-steady" sound and eventually into reggae.

Before that happened, however, Caribbean immigrants brought ska to England, where it attracted a cult following. The factory town of Coventry in the British Midlands was a hot spot for ska activity, as large numbers of blacks settled there to work in the British auto industry. By the late 70s, Coventry's fortunes mirrored Detroit's, with high unemployment and the attendant unrest. Musically, the good-time sound of ska was being introduced to the lyrical intensity and anger of the punk movement. Driving this movement was the Specials, led by Jerry Dammers, a white record-store clerk, who formed the multiracial band in 1978.

Not surprisingly, the Specials in their various incarnations form the centerpiece of The 2 Tone Story. 2-Tone is Dammers's label, but more important, Dammers's band led the way for the other ska bands throughout the movement.

The main irony of the Specials' songs, and in fact of the entire ska movement, was that lurking just beneath the "happy," infectious dance beat were often chilling stories of the racial divisiveness and economic deprivation that characterized the dawning of the Thatcher era. This is evident on their debut single, "Gangsters," released in July 1979. The steady backbeat of drummer John Bradbury and the bass of Horace Panter combine with Dammers's lilting keyboards to turn rock's traditional 4/4 beat inside out, providing an insistent dance groove.

Meanwhile Terry Hall's anguished tenor sings a tale of tongue-in-cheek urban chaos that takes a swipe at the British record industry:

Why must you tape all my phone calls,

Are you planning a bootleg LP?

Said you've been threatened by gangsters,

Now it's you that's threatening me.

Can't fight corruption with conscience

They use nylon to commit crime

I dread to think what the future will bring

Living in a gangster town.

DON'T CALL ME SCARFACE!

A Catch 22 says if I sing the truth

they won't make me an overnight star.

Don't offer a cent for protection

They use nylon to commit crime

I dread to think what the future will bring

when we're living in a real gangster town.

Propelled by the success of "Gangsters" and a spirited cover of Robert Thompson's "Rudi, a Message to You" produced by Elvis Costello, the Specials released their long-playing debut in 1980. With Costello behind the board, The Specials represents ska's most notable achievement and one of the decade's finest pop albums of any kind. It includes the band's first two singles and 13 other songs ranging from the rambling lament of "Blank Expression" to the social satire on teenage pregnancy of "Too Much, Too Young." Both songs are featured on The 2 Tone Story, the latter in a live presentation culled from the 1981 album, Dance Craze. It proves these lads could play. While Hall sings disdainfully about ugly babies and the benefits of contraception, an angry blend of Lynval Golding and Roddy Byers's Stones-like guitars merges with the trademark ska beat provided by Bradbury and Panter. The resulting cascade of sound almost dares the audience to stay in their seats.

Unfortunately, the reign of the Specials as ska kings was short. Their second studio album, More Specials, was released late in 1980 amid rumors of internal strife, which the record confirms, lacking the joy and intensity of their debut. The 2 Tone Story features only one track from this album, the likable but inconsequential "International Jet Set."

Before disintegrating, though, the Specials managed to record perhaps their most noteworthy song. Released in June 1981 as riots raged in Brixton and Liverpool, "Ghost Town," presented in its 12-inch version on The 2 Tone Story, evoked a picture of a racially divided England coming apart at the seams. Driven by the eerie trombone playing of Rico, a Jamaican reggae veteran who played on a number of Specials songs and also recorded instrumental albums for 2-Tone, "Ghost Town" is that rare political song that perfectly captures the mood of the time; it gave the rioting rude boys of all racial and political persuasions reason to pause.

This town is coming like a Ghost Town

All the clubs are being closed down

This place is coming like a Ghost Town

Bands won't play no more,

Too much fighting on the dance floor.

Do you remember the good old days before the Ghost Town

We danced and sang and the music played in our boom town.

This town is coming like a Ghost Town

Why must the youths fight against themselves

Government leaving the youths on the shelf

No jobs to be found in this country

Can't go on no more

People getting angry.

For all intents and purposes, "Ghost Town" marked the end of the Specials. Hall, Golding, and vocalist Neville Staples split off to form the sporadically brilliant Fun Boy Three, then Hall basically went solo in 1985 with the Colourfield. Dammers vanished briefly from the music scene, becoming increasingly involved in antiapartheid politics (the Specials had participated in the Rock Against Racism movement in England of 1981 at Dammers's urging).

After a three-year absence, Dammers released In the Studio under the name of Special AKA with a number of ska veterans and original Specials drummer John Bradbury. While the album lacked the danceability of Specials music, it contained a number of compelling songs, such as the politically correct "War Crimes" and "Racist Friend" and the fiercely inspirational "Free Nelson Mandela," which brought Dammers worldwide acclaim among human rights activists. Produced once again by Costello and featuring him and a cast of other notables on backing vocals, the song immediately became the anthem for millions clamoring for the release of the long-imprisoned ANC leader. As writer Robin Denselow recounts in his outstanding book When the Music's Over: The Story of Political Pop, the song became hugely popular in Mandela's native land: "It must have been extraordinary for a white songwriter from Coventry, in the British Midlands, to turn on the television news and see demonstrators in Soweto singing his song." Extraordinary indeed.

Since the release of In the Studio, Dammers has been musically silent, with the exception of a song contributed to the Absolute Beginners sound track. He has been concentrating on political activities. He cofounded with Paul Weller and Billy Bragg the Red Wedge political movement in England, the banner under which British musicians united for the Labour Party in the 1987 elections. He also was instrumental in creating the pressure group Artists Against Apartheid (AAA) to educate performers about the evils of playing in South Africa. In that role he has wrangled with Paul Simon over his use of South African musicians on his Graceland album and also assisted in the organization of the July 11, 1988, Nelson Mandela 70th-birthday tribute at Wembley Stadium.

After the Specials, the most influential ska band was the Beat, formed in Birmingham. (They are known as the English Beat in the U.S. due to name similarity with an LA band.) The Beat's brilliance has been overshadowed by the commercial achievements of its alumni. Before Dave Wakeling and Ranking Roger went on to moderate success as General Public, and before guitarists David Steele and Andy Cox found superstardom with Fine Young Cannibals, the Beat combined hard-edged guitars and power-pop melodies with Wakeling's quirky voice and Ranking Roger's "toasting"--ska's version of rapping--to create a sound unheard before or since. Their contributions to The 2 Tone Story include the stop-go dance number "Ranking Full Stop" and a live version of the dark "Mirror in the Bathroom," featuring the ska legend Saxa on saxophone.

The Beat went on to greater fame on the IRS label, recording three fine albums before their breakup in 1983. On their 1979 long-playing debut, Just Can't Stop It, which included their first two singles, the Beat continued ska's reputation for highly political dance music with songs like "Stand Down Margaret," a derisive ode to the prime minister that unfortunately is still relevant a decade later. (Costello did a version on his 1983 tour and Bragg sang a gruff cover during his 1986-'87 swing through the U.S.)

The Beat did well in the U.S. in the early years of the 80s, moving almost imperceptibly toward the commercial mainstream but without losing sight of their ska origins. Their final and finest album, 1982's Special Beat Service, was more pop than ska; the first tune on each side--"I Confess" and "Save It for Later"--opts for a rather conventional pop sound, the former being driven by dance-hall piano and the latter by straightforward rock guitar (witness Pete Townshend's acoustic cover of it). However, songs such as the organ-driven "Jeanette" and the joyful reggae-tinged "Ackee 1-2-3" betray the Beat's steady devotion to their 2-Tone roots.

The 2 Tone Story also contains some early work by one of Britain's most enjoyable pop exports of the 80s, the London band Madness. While the Specials and the Beat sought to achieve some level of ska authenticity through their multiracial makeup and their use of veterans such as Rico and Saxa, the six white boys who make up Madness have no such pretensions. Instead, they paid homage to the musical style they were appropriating in the selection of their name, which is the title of a hit by 60s ska star Prince Buster, and in the title of their first single, "The Prince," which appears along with a live version of "One Step Beyond" on The 2 Tone Story. Madness's sound on both these songs and on their debut album, One Step Beyond, produced by Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley (who would be involved with most of Madness's recordings and would produce some of Elvis Costello's best-sounding albums, most notably Punch the Clock), is a heady combination of ska with the rough-cut spontaneity of a drunken bar band. The self-described "nuttiness" of Madness has few points of comparison in recent pop history; closest perhaps is the LA ska band Fishbone, whose repertoire includes a version of the theme from the Fat Albert cartoon show.

Sadly, the all-white makeup of Madness attracted the undesirable attention of England's skinheads, racist working-class kids loosely affiliated with the fascist National Front movement. Trouble struck when Madness and the Specials toured together and the skinheads heaped racist epithets on the black members of the Specials. The concert made national headlines, and while Madness went to extremes to disassociate themselves from the skinheads, the event temporarily marred the harmonious feeling of the neo-ska movement and only underscored the incendiary racial situation in Thatcher's England.

Madness went on to score a number of British hits throughout the decade and managed even to liven up the U.S. charts with "Our House," a three-minute essay on British home life. The band became increasingly "serious" while attempting to maintain a shred of their earlier lunacy. Of their later albums, The Rise and Fall and Keep Moving are the most notable.

The rest of The 2 Tone Story contains songs from less influential but not necessarily less interesting bands. The Selecter, ska's prefab band, is featured on four tracks. The instrumental "The Selecter" was the B-side of the Specials' "Gangsters" single, recorded by Specials drummer Bradbury and Joel Davis, a friend of Dammers. After the song became a hit in its own right, Davis was obliged to put a band together and the result was the Selecter, which prominently featured chanteuse Pauline Black. They went on to record a number of catchy hits including "Three Minute Hero" and "Too Much Pressure," both featured on The 2 Tone Story. Also on the album are songs by ska girl group the Bodysnatchers, featuring the alluring vocals of Rhoda Dakar, who later resurfaced on the Special AKA album. The wild sound of Bad Manners, fronted by Buster Bloodvessel, is represented with their live version of "Lip Up, Fatty," a hilarious tribute to obesity driven by a crack three-piece horn section. Bad Manners' live shows were much more indicative of their ska talents than their recorded work, but they always gave Madness a run for the title of ska's silliest band.

The 2 Tone Story isn't a definitive commemoration of the ska movement. Rather, with the exception of the Specials, whose essential recordings are captured here, the album serves mostly as a teaser to get you skanking on down to the record store to check out the collections of the Beat, Madness, et al--a primer on one of the most compelling pop chapters of the last decade. Ska presented a triumphant symbol of integration and harmony to a nation in the throes of an ugly transformation characterized by racial and economic brutality. Whether you listen to it for its politics or purely for its irresistible rhythms, you'll likely be left wondering why America virtually ignored its enticing sound and instead chose the new romantic dreck of bands such as Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet to spearhead the 80s wave of the British invasion.

https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/ska-story-the-sound-of-angry-young-england/Content?oid=875398

How Skinheads Transformed From Inclusive Youth Movement Into Racist Hate Group

By All That's Interesting

Published March 7, 2017

Updated April 4, 2017

Before linking with Neo-Nazism, skinhead culture started among young English and Jamaican working-class communities in 1960s London.

They just weren’t having it anymore. Sick of the hippie movement’s empty promises and the austerity that pervaded British government at the time, skinheads emerged in 1960s London and rallied around one thing: to wear their working-class status as a point of pride.

It was only a matter of time before radical right-wing politics buried that mission in favor of open racism and ultimately Neo-Nazism, however. In The Story of Skinhead, Don Letts — one of the original London skinheads — traces this story, and offers a sobering, uneasy tale of how easily racism can creep into working class politics.

The First Wave

The first wave of skinheads stood for one thing: embracing their blue collar status. Many self-identifying skinheads at the time either grew up poor in government housing projects or “uncool” in suburban row houses, and felt isolated from the hippie movement, whose members they believed embodied a middle class worldview — and one that didn’t address their unique concerns.

Changing immigration patterns also shaped the burgeoning culture. Around the time, Jamaican immigrants began to enter the U.K., and many of them lived side-by-side with the working-class English. This physical proximity offered a chance for sustained cultural exchange, and soon enough English kids latched on to Jamaican reggae and ska records. In a nod to the mod and rocker subcultures that preceded them, skinheads donned slick coats and loafers, buzzing their hair in a quest to become cool in their own right — and to disassociate themselves from the hippie movement.

Racism Creeps In

By 1970, the first generation of skinheads had begun to frighten their peers. Popular media exacerbated this fear, with Richard Allen’s 1970 cult classic novel Skinhead — about a a racist London skinhead obsessed with clothes, beer, soccer, and violence — serving as a prime example.

The second wave of skinheads didn’t take umbrage at this portrayal; instead, they began to reflect and project it — particularly the racism. Indeed, Skinhead became the de facto bible for skinheads outside London, where football fan clubs were quick to take the subculture — and its constitutive aesthetics — up.

It didn’t take long for political groups to attempt to use the growing subculture for their own gain. The far-right National Front Party saw in the skinheads a group of working-class males whose economic hardships may have made them particularly sympathetic to the party’s ethno-nationalist politics.

And thus, the party began to infiltrate the group. “We were trying to think about race wars,” said Joseph Pearce, a now repentant National Front member who wrote propaganda for the group throughout the 1980s, in The Story of Skinhead. “Our job was to basically disrupt the multicultural society, the multi-racial society, and make it unworkable.”

“[Our goal was to] make the various different groups hate each other to such a degree that they couldn’t live together,” Pearce added, “and when they couldn’t live together you end up with that ghettoized, radicalized society from which we hoped to rise like the proverbial phoenix from the ashes.”

National Front would sell propagandistic magazines at soccer matches, where they knew they would reach a massive audience. It was an economical move: even if only one in ten attendees bought a magazine, that’s still 600 to 700 potential recruits.

In its efforts to recruit more party members, the party also took advantage of rural conditions in which many skinheads found themselves. One former skinhead featured in the The Story of Skinhead recalled that the National Front opened up the sole nightclub within dozens of miles of one rural community — and only allowed members to come inside. Those who wanted to dance had to listen to propaganda.

Over time, right-wing efforts to co-opt skinhead culture began to rot the latter from within. For example, Sham 69, one of the most successful punk bands in the 1970s and one with an unusually large skinhead following, stopped performing altogether after National Front-supporting white power skinheads rioted at a 1979 concert.

Barry “Bmore” George, a skinhead forced out due to racially-charged politics’ entry into and commandeering of the subculture, put it this way:

“I got asked a lot by people, about like well, you seem to know a bit about skinheads, I thought they were all racists… Depends on where you start reading your story. If you go right back and start your story right back at the beginning, and get yourself a good foundation of your knowledge of skinhead culture and where it was born from…You know what it was about. You can see where it was distorted. It did start off as one thing; now it’s branched to mean untold things.”

The end of the 1970s also saw the last flare of multicultural acceptance with 2 Tone music, which blended the 1960s-style ska with punk rock. And as that genre petered out, Oi! music began to pick up speed, combining the working-class skinhead ethos with punk rock energy.

Right-wing nationalists co-opted this genre from nearly the very beginning. Strength Thru Oi!, a famous compilation album of Oi! music, was — supposedly mistakenly — named after a Nazi slogan, and featured a neo-Nazi on the cover who would be convicted of attacking black youths at a train station that same year.

When that man was released from prison four years later, he would go on to provide security for a band called Skrewdriver. While it started off as a non-political Oi! band, over time it would grow close with various right-wing political groups and eventually become one of the most influential neo-Nazi rock bands in the world.

Music and violence became enmeshed, perhaps most saliently seen in the 1981 Southall riot. On the day it transpired, two busloads of skinheads headed to a concert located in Southall, a London suburb which at the time was home to a large Indian and Pakistani population.

Those skinheads found an Asian woman on the way to the concert and kicked her head in, smashing windows and vandalizing businesses as they proceeded. One 80-year-old retiree told The New York Times that the skinheads were, “running up and down asking where the Indians lived. It was not nice at all.”

Outraged, Indians and Pakistanis followed the skinheads to the pub where the concert took place. An all-out, racially-charged brawl took place soon after.

“The skinheads were wearing National Front gear, swastikas everywhere, and National Front written on their jackets,” a spokesman for the Southall Youth Association told The New York Times. “They sheltered behind the police barricades and threw stones at the crowd. Instead of arresting them, the police just pushed them back. It’s not surprising people started to retaliate.”

The Southall incident solidified skinheads’ perception as an openly racist and violent subculture, and the subsequent generations of the subculture — particularly those in U.S. prisons — have worked to ensure that the associations stick. As for the working-class ethos that propelled the subculture in the first place?

Its progenitors don’t think there’s any chance of getting that narrative back.

“Those ideologies have been sold to people that skinhead is associated with [fascism].” Jimmy Pursey, the lead singer of Sham 69, said. “It’s like a branding.”

https://allthatsinteresting.com/skinheads-history

Who Is “Rudy” in Ska Music?

It takes only a brief dip into the ocean of ska to realize that an overwhelming amount of songs make a reference to somebody named “Rudy”. So, who is this elusive character?

Back in the days of first wave Jamaican ska, frustrated youth in poorer areas of Kingston, Jamaica turned to petty crime. Known as “rude boys”, these youth sported aesthetics and attitudes inspired by American jazz musicians and gangster films, wearing suits and porkpie hats, and behaving rambunctiously and rebelliously.

Many of these rude boys were hired by soundsystems (organizations of disc jockeys, engineers, and MCs) to gatecrash their competitors’ street parties. Such disruptions became so commonplace that artists started addressing rude boys in their lyrics, often shortening the moniker to “rudy”.

A decade later, 2 Tone took the name and ran with it, with fans referring to themselves as “rude boys” or “rude girls”. The Specials’ famous tune “A Message To You, Rudy” references the popular subculture:

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/ska-music/

The rude boy subculture arose from the poorer sections of Kingston, Jamaica, and was associated with violent discontented youths.[3] Along with ska and rocksteady music, many rude boys favored sharp suits, thin ties, and pork pie or Trilby hats, showing an influence of the fashions of American jazz musicians and soul music artists. American cowboy and gangster/outlaw films from that period were also influential factors in shaping the rude boy image.[4][5] In that time period, unemployed Jamaican youths sometimes found temporary employment from sound system operators to disrupt competitors' dances (leading to the term dancehall crasher).[6] The violence that sometimes occurred at dances and its association with the rude boy lifestyle gave rise to a slew of releases by artists who addressed the rude boys directly with lyrics that either promoted or rejected rude boy violence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rude_boy

"The figure of the rude boy with his swagger and casual disrespect for the law harks back to older archetypes like the semi-mythical Stagger Lee character in black American folk blues, the bad man who seems invincible

depict a collective of sharply dressed individuals, who exemplify an important yet undocumented subculture …

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/24/rude-boys-jamaican-subculture-photography-exhibition

The Evolution Of Rude Boy Culture

October 12, 2013 By Douglas Smythe

You’ve probably heard the term ‘rude boy’ brandished around quite a bit. In modern society the rude boy wears a tracksuit, a flat peak cap and listens to dirty stinking Grime music. However, there was a time when a rude boy wouldn’t be seen dead in a tracksuit. The original rude boy inhabited a smart and slick appearance, listened to Reggae, Rock-Steady and Ska music and shared beliefs surrounding politics and culture.

History Of The Name

Just like its Jamaican roots suggest the term ‘rude boy’ first came alight in 1950s Jamaica. It was a term that was commonly associated with adolescent criminals in the poorer sections of Jamaica, noticeably Kingston. Violence on the streets went hand in hand with the early rude boy, activities such as gate crashing rival sound systems became a familiar sight. The rude boy would aspire to dress in the latest street fashion which included razor sharp suits, thin ties and hats such as pork pies or trilbies. An image that was clearly inspired by American gangsters, Jazz musicians and Soul artists at the time; however it was the Jamaican sound of 60s Ska music that influenced the benchmark rude boy.

How Music Contributed

It was Ska music that helped to transform the negative connotations associated with the rude boy. Jamaican Ska musicians sought to speak to the youth about their violent tendencies and urged them to channel their culture’s attention towards a much more political motivation. The song ‘Message to You, Rudy’ by Dandy Livingstone in 1967 is a prime example of Ska musicians reaching out to the rude boy faction. This song would later be covered by British Ska group The Specials.

The origin of Ska music derived from Jamaican Reggae and Rocksteady, as well as being the hybrid child of Carribbean Mento, Calypso, American Jazz and Rhythm and Blues. However, music historians argue that Ska music takes up three noticeable periods: in the 1960s – Original Jamaican Ska music, in the late 70s – English 2 Tone Ska and in the 90’s the third wave of Ska – American Ska Punk.

Overseas Rudeboy

It wasn’t only in Jamaica where the rude boy could be found. In 1960’s Britain, the influx of Jamaican migrants into urban city dwellings helped expose Britain to the rude boy. Yet, it was in the late 70’s where rude boy culture became truly embraced and found a home within Britain. The British streets smelt aromas they’d never smelt before, laid eyes on new fashion trends and were blessed with the sounds of authentic Jamaican Ska, Reggae and Rocksteady. It was this introduction that sparked the infusion of British styles with Jamaican heritage. Trilby hats were still donned upon the head of the rude boy but Dr Marten’s boots and Fred Perry polo shirts were now the staple attire and uniform of the white British rude boy.

2 Tone Era

Ska formed its second wave sound in the 2 Tone era. 2 Tone grabbed elements from original Ska, Punk Rock, Rocksteady and Reggae to create a faster tempo style of music. Ska now had more edge and bite, including a huge influence from brass instruments. Groups such as The Specials helped to pave the way for the new sound, and more importantly they managed to unite black and white people when tensions were high within smaller racist skinhead cultures.

Similar to Jamaican Ska musicians, The Specials resonated with the British youth, showing sympathy and highlighting issues such as unemployment and racism. The Specials single ‘Ghost Town’ being the most notorious example. Madness also began to make the Ska sound a lot more popular. Madness threw both Ska and the rude boy image into a wider public domain with hits such as ‘One Step Beyond’ and ‘Our House’.

Modern Day Rudie

Rude boys have come a long way from the streets of Kingston. You’ll now hear the likes of Dexter or Fatboy in Eastenders calling everyone and anyone a ‘rude boy’. The term was maintained by Hip Hop and Grime musicians, and although a different style of music, there’s still a running theme to the rude boy. It may have been diluted and slightly tainted from its founding roots but the rude boy is still regarded as a working class member of society, living in inner cities and sharing a huge passion for music.

Read more:

http://howtogrowamoustache.com/the-evolution-of-rude-boy-culture/#ixzz5c1fo36b8

Summary/Conclusion:

-Ska originates from 1950s Jamaica.

-It precedes reggae and the beat is heavily influenced by American R&B music. It’s made for dancing. The music is upbeat, quick and exciting.

- The "rude boys" were a Jamaican subculture of the 1960s. Rude Boys were generally unemployed, impoverished Jamaican teens who were hired by sound system operators (mobile DJs) to crash each other's street dances. These interactions often led to further violence and the Rude Boys frequently formed feuding gangs. Fashionable clothing for rude boys was American gangster wear. The Rude Boy culture became a huge source for ska lyrics.

-In the 70s, Caribbean immigrants brought ska to England, where it attracted a cult following. The factory town of Coventry in the British Midlands was a hot spot for ska activity, as large numbers of blacks settled there to work in the British auto industry. Soon enough English kids latched on to Jamaican reggae and ska records. In a nod to the mod and rocker subcultures that preceded them, skinheads donned slick coats and loafers, buzzing their hair.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1 -Workshop

We met our team-members for the first, introduced ourselves and spoke about what we could bring to the table.

We each had to bring in three unwanted items of clothing that was thrown into a big pile for each of the ten teams to work from. We were then our tribe and music genre, ours being - Mustang Nepal and Ska.

We had a few hours to create an outfit, story and performance. In the beginning I felt lost as my strengths do not lie in design and I didn’t want to encroach on people who are talented in that area. I tried to offer my opinion and help where I could but only felt like I was truly contributing when I began to help Kata construct her speech about climbing Mount Everest, breaking down borders and overcoming obstacles together. I tried to transcribe ideas and facts into a cohesive story which I believed we did manage in the end. I think I will put my writing/language/communication skills forward for my contribution to this project alongside working with my hands creatively.

0 notes