Text

STACKEDNATURAL ⇉ 125/327 (part 1)

8.8 Hunteri Heroici

Written by Andrew Dabb

Directed by Paul Edwards

Original Air Date: November 28, 2012

919 notes

·

View notes

Text

FUCK I just remembered HOHT had a character that was both a hockey player and an artist, i REALLY need to get some new ideas

When I tagged that last post as Carter Delmont it suggested Carter Jiang, i REALLY need to find some new names lol

1 note

·

View note

Text

When I tagged that last post as Carter Delmont it suggested Carter Jiang, i REALLY need to find some new names lol

1 note

·

View note

Text

guy who acts like a wounded animal when drunk and like a giggly drunk when wounded

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

bro I love how your new girlfriend is exactly like me! but like.. she’s a she yknow.. haha! I kinda resent her for being able to spend that extra time with you, for being closer to you than our platonic binds will let us be.. but it’s ok! she’s a lot like me so, in some corner of your mind, when you make love to her.. ah, well lost my train of thought. anyways I guess I approve of her, she seems to make you happy, she seems to challenge you, so good pick! by the way, off topic but I’m in love with you and have been over the course of our entire friendship, seeing you happy with someone so close to my personality is heartbreaking because I just know that if I were born with tits we would’ve been together already. hah, but whatever! doomed by the narrative! see ya champ!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, to you sci-fi/fantasy writers out there (and maybe some others, but this is mainly for things that can’t really be researched irl), if you want to write a character who is a driven, passionate expert on something, don’t write about them rambling indifferently about some boring, mundane part of it. Give them a deep, intense hatred of some oddly specific wow-I-did-not-even-know-that-was-a-thing-and-it-would-have-never-occurred-to-me-that-it’s-a-bad-thing thing they’ll gladly rant about.

Write a dragon rider who really fucking hates it when a dragon is trained to bow while being reined. A space ship engineer who is pissed off when perfectly good antimatter ship has been adapted to run on neutral matter. A historian who is still not over the massive failures of a general who lost a specific battle 300 years before she was born.

The guy currently giving us a series of lectures on the restoration of historical buildings really, really hates polymer paint. At the artisan school our stained glass teacher really hated this one specific Belgian artist - we never really figured out what did that guy even do, but he’s been dead for over 200 years and our teacher was glad that at least he’s dead.

Experts don’t just know things you’ve never thought about. They’ve got strong opinions about it.

66K notes

·

View notes

Text

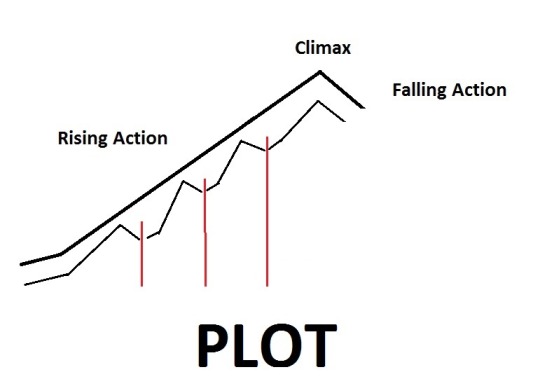

10 Tips for The Middle of Your Story

Is the middle of your story slow, confusing or unclear? Here are 10 quick things to consider when writing your story’s middle:

1) Have your character(s) try and fail. Progress and setbacks create a story. Wrap your reader in the suspense of if your protagonist will actually reach their end goal.

2) Weave in your subplots. Subplots should not only run parallel with your main plot, but also intertwine within it. Don’t forget or neglect them! Choose subplots that compliment or contrast your main story.

3) Make sure your protagonist has a clear goal that powers the plot. Don’t forget about your side characters, either. Giving them goals can add realism to their character while also impacting the story.

4) More, more, MORE obstacles. This could include:

- Physical obstacles (terrain, actions of the antagonist, wounds)

- Mental obstacles (self-doubt, flaws, emotions)

- Relationship obstacles (arguing, fighting, betrayals)

5) Do NOT make things easy for your protagonist. The middle is the time for struggles and drama, but also fun and games. This is essentially the heart of your story. When one conflict is solved, an even bigger one arises. Your protagonist must fall and get back up. Torture them, reward them and watch them grow.

6) Strengthen existing characters and introduce new ones. New characters can bring conflict, drama, solutions to the story. Overall, they make your readers curious about who they are and if they’re here to stay.

7) Show your character’s flaw in action. Put them in situations where their flaw only worsens the scenes. Overtime, they begin to realize their faults and will develop (positively or negatively) as you near the end.

8) Don’t forget about your theme. To keep your story consistent, never lose sight of your themes.

9) Consider adding a ‘false’ climax towards the end of the middle. This is an event that imitates the real climax, but instead of things going well for your protagonist, they end up failing. This can be followed by your character’s “darkest hour”, where they give up all hope before regaining it and proceeding to the real climax.

10) Consider adding a Mac Guffin. An object, item or idea that motivates your characters. They need to obtain this object to reach their goals. Finding a key to open the door, piecing together a map to get to the treasure, etc.

Instagram: coffeebeanwriting

📖 ☕ Official Blog: www.byzoemay.com

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Advice & Tips on Metaphor and Symbolism

While I do have a few essays and resources that would allow me to write something up on the theories of metaphors, I don’t find them that useful for application. So, instead, I am just going to describe a few processes that I do when I wish to add in some metaphors into my writing.

Sort By Character - The very beginning of my ‘metaphor construction’ process starts when I have created my character, or sometimes even during the midst of. For the purposes of explaining this, I am going to use one of my characters, who is called Saramil, as an example. Saramil is a young, wealthy member of high aristocracy, who works as a pastoral poet and social commentator to escape facing the prospect of inheriting his family’s (fairly boring, or at least he’d say so) land investment business. This kind of character naturally lends itself to images of gold and jewels, as obvious symbols of wealth, but what else can be taken out of these images?

Read Books With Similar Characters - While it seems to be every author’s goal to create a completely unique character, tropes and reoccurring patterns in literature are inescapable, but are necessary in the implementation of metaphors: established images make it more possible for readers to understand new creative metaphors, and are vital in forming conventional ones (an example of a conventional metaphor being “time is running out”). So, if you find a character in a book that is similar to yours in either goals or lifestyle, pay close attention to how the author describes them. Going back to the example of my character, a character that stuck with me was Daisy Buchanan from The Great Gatsby, and found the line “her hand was wet with glistening drops as I took it to help her from the car”. The idea of nature replicating a jewel had me come up with lines such as “dripping in cold gemstones” for my own descriptions.

Research The Object - What I mean by this is actually look into what you want to make a comparison with. So, say I want to use jewels as a reoccurring symbol for Saramil, my next step is to research jewels. Questions should naturally arise from this process: What kind of jewel? What colours? Does it have any historical or cultural context behind its symbol? If you are able to with the particular image in mind, try and get a hold of the actual item and look at it for yourself. After rummaging through my mother’s jewellery box and scanning through the catalogues of auction houses, I decided to align Saramil with the symbol of an opal, since these are jewels that aren’t one colour, and change with the light and perspective, just as I want his character to reflect. This also aligns quite nicely with Shakespeare’s usage of the symbol: in Twelfth Night, Feste tells Count Orsino that “thy mind is a very opal”, to refer to his easily-changeable mind.

Branch Out - Something I try to do with as many of my metaphors as possible is interconnect them. What I mean by this is, after I have my list of symbols for each character, I try to see what connects them together, with hopes that I can find something new. One example I have already included in this explanation: both raindrops and jewels are glistening, therefore the symbols can be simultaneously recognised by a reader. One of the most established focuses of symbolism in literature is that of light and dark. Light, as one of the first creations of God, is commonly linked to as goodness and purity, but it makes for a more intriguing read if one is to subvert established images like this. To do this, I linked the glittering light of reflections of gems with a gemstone’s physical coldness and lack of value to substance: gems are only worth their appearance, since they can be used for little else directly. With the wider imagery of “light” and “reflection” now attached to the character, lots of doors are opened for metaphorical possibility.

Don’t Delete Any Metaphors You Make - This is really a comment on all writing or artwork produced, but if you come up with a metaphor, but decide that you don’t think it fits your character, don’t delete it! Make a document for them, or keep them in a scrapbook if you hand-write.

If All Else Fails, Google - If you type in “[Insert Object Here] Symbolism” or “Symbols of [Insert Personality Trait Here]” into Google, you are bound to come up with results. Just be mindful of what you take as truthful in application of your character.

I hope that helps! I can’t say my writing ‘method’ is… Well, much of a method, but I tried to make the tips coherent. Happy writing!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

So my problem with most ‘get to know your character’ questioneers is that they’re full of questions that just aren’t that important (what color eyes do they have) too hard to answer right away (what is their greatest fear) or are just impossible to answer (what is their favorite movie.) Like no one has one single favorite movie. And even if they do the answer changes.

If I’m doing this exercise, I want 7-10 questions to get the character feeling real in my head. So I thought I’d share the ones that get me (and my students) good results:

What is the character’s go-to drink order? (this one gets into how do they like to be publicly perceived, because there is always some level of theatricality to ordering drinks at a bar/resturant)

What is their grooming routine? (how do they treat themselves in private)

What was their most expensive purchase/where does their disposable income go? (Gets you thinking about socio-economic class, values, and how they spend their leisure time)

Do they have any scars or tattoos? (good way to get into literal backstory)

What was the last time they cried, and under what circumstances? (Good way to get some *emotional* backstory in.)

Are they an oldest, middle, youngest or only child? (This one might be a me thing, because I LOVE writing/reading about family dynamics, but knowing what kinds of things were ‘normal’ for them growing up is important.)

Describe the shoes they’re wearing. (This is a big catch all, gets into money, taste, practicality, level of wear, level of repair, literally what kind of shoes they require to live their life.)

Describe the place where they sleep. (ie what does their safe space look like. How much (or how little) care / decoration / personal touch goes into it.)

What is their favorite holiday? (How do they relate to their culture/outside world. Also fun is least favorite holiday.)

What objects do they always carry around with them? (What do they need for their normal, day-to-day routine? What does ‘normal’ even look like for them.)

49K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Quick Character Tips

Here are a handful of quick tips to help you write believable characters!

1. A character’s arc doesn’t need to grow linearly. Your protagonist doesn’t have to go from being weak to strong, shy to confident, or novice to professional in one straight line. It’s more realistic if they mess up their progress on the way and even decline a bit before reaching their goal.

2. Their past affects their present. Make their backstory matter by having their past events shape them into who they are. Growing up with strict parents might lead to a sneaky character, and a bad car accident might leave them fearful of driving.

3. Give reoccurring side characters something that makes them easily recognizable. This could be a scar, a unique hairstyle, an accent, or a location they’re always found at, etc.

4. Make sure their dialogue matches their personality. To make your characters more believable in conversation, give them speech patterns. Does the shy character mumble too low for anyone to ever hear, does the nervous one pace around and make everyone else on edge?

5. Make your characters unpredictable. Real people do unexpected things all the time, and this can make life more exciting. The strict, straight-A student who decides to drink at a party. The pristine princess who likes to visit the muddy farm animals. When character’s decide to do things spontaneously or in the heat of the moment, it can create amazing twists and turns.

6. Give even your minor character’s a motive. This isn’t to say that all your characters need deep, intricate motives. However, every character should need or want something, and their actions should reflect that. What’s the motive behind a side character who follows your protagonist on their adventure? Perhaps they’ve always had dreams of leaving their small village or they want to protect your protagonist because of secret feelings.

Instagram: coffeebeanwriting

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

Structuring Your Relationship Plotline

A relationship plotline will be present in most stories. It will have a relationship arc and follow the principles of plot (according to relationships), but like any plotline, it also needs a sense of structure. It needs to be organized in a coherent way for the audience, so they can follow and appreciate the progression or deterioration of the relationship.

This article will help you structure the relationship plots you're writing--whether the relationship features love interests, friends, family, allies, rivals, or even enemies (and everything in between).

Now . . . I admit, I've been debating a lot about how to write this article, if I should put forth a general foundational approach to the structure, or if I should get more specific and offer a beat sheet. The more I thought about it, the more I realized the latter would be pretty complicated, since each relationship plotline can be affected by the external and internal plotlines and could have a different relationship arc. It also seems I'd need a beat sheet for each relationship arc type, and even within those, there can be variations.

That might be a project for later down the road.

Plus, when you understand the foundational principles first, the beat sheets make more sense and you know how to stray from them for the effect you want.

When you understand the foundational principles, you're more likely to be a chef, not a cook.

So, with that said, I've opted for the former today . . . but next time, I will have an article on key beats (and how they are most frequently structured) that you can manipulate to suit your relationship plotline.

Here are a couple of things for you to keep in mind . . .

- How much you develop your relationship plotline may depend on how prominent the plotline is in the story. A relationship that works as an A Story must be developed enough to carry the narrative and all the critical moments must happen on page. A relationship that works as the C Story will be more understated and may have more happening off page. There are a lot of ways to play with the relationship plotline (as I've discussed), so how much attention you give it and how it is interweaved with the other plotlines will depend on your story.

But regardless of how prominent the plotline is, if it's a plotline it still needs the basic elements of plot and it still needs to be delivered to the audience through structure.

- Where the relationship plotline starts may depend on how prominent the plotline is. This brings me to the next section.

Does the Relationship Plotline Start in Act I or Act II?

Some approaches to structure (such as Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder) state that the relationship plotline starts at the beginning of Act II. In fact, in many stories, the beginning of Act II is marked by the protagonist meeting the central relationship character.

The protagonist falls from the high of Act I, enters a "new world" (literal or figurative), and meets someone there. Examples include:

Pixar's Soul

Elf

A Quiet Place, Part II

But this is clearly not how all stories go. If you have a relationship plotline for the A Story, it may be unrealistic and unwise to wait until Act II to have the characters meet. It's the primary plotline! So you probably need to have them meet in Act I. Some examples of this include:

Pride and Prejudice

My Big Fat Greek Wedding

The Fault in Our Stars

And even if the relationship plotline isn't the A Story, it's not unusual for the protagonist to meet and begin interacting with the central relationship character in Act I.

Then, of course, in some stories, the protagonist already has a relationship with the other character when the narrative opens.

So what's going on here? Where should you start your relationship plotline?

Well, if it's the A Story, you probably need to start it in Act I. But sometimes you can dance around this by having two key relationships. You could also, theoretically, start with a strong internal or external plotline in Act I, and then pull up the relationship plotline for Act II and make it the most prominent. But that can be pretty tricky.

There are so many different ways this can all manifest, that it can make any head spin if you try to be too rigid.

Just know that the relationship plotline can start in Act I or Act II--pick what is best for your story. If it starts in Act II, you are writing a "two-act relationship plot." And if it starts in Act I, you are probably writing a "three-act relationship plot." And, theoretically, you could have a relationship plotline that only lasts one act (likely through the middle).

. . . see why I decided to keep it general and foundational?

Relationship Turning Points within Acts

Recall previously that I gave a lengthy explanation on turning points for relationship plotlines. If you missed it or are new here, I recommend you go read at least that one section before continuing this article, so you can better understand what I'm going to be talking about.

But in case you don't want to or just want a very simplistic reminder, a turning point is an action or revelation that changes the direction of the plot. In a relationship plotline, a turning point changes the direction of the relationship, often in ways that can't be undone.

If you've been in the writing community for a while, you are probably familiar with some key structural beats, such as . . .

Plot Point 1, Crossing the Threshold, Break into Two (all different terms for--nearly--the same moment)

Midpoint

Plot Point 2, The Ordeal, All is Lost (all different terms for--nearly--the same moment)

Climax

Guess what?

Stripped away of all their fanciness, these are actually all just turning points. They are major turning points, true, but at the most basic level, they are turning points.

They are actually all act-level turning points.

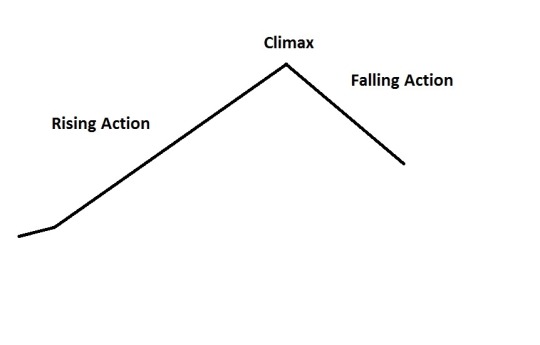

Each act should follow basic story structure:

This means each act should have its own climax (aka, major turning point).

Now, many people split Act II into two parts, at the midpoint. While I think you can argue this actually makes the story four acts, to keep things from being too confusing, I try to stick to popular terminology. So I call these Act II, Part I & Act II, Part II.

With this in mind, you can view your story like this:

The climax of Act I is . . . Plot Point 1, Crossing the Threshold, Break into Two

The climax of Act II, Part I is . . . the Midpoint

The climax of Act II, Part II is . . . Plot Point 2, The Ordeal, All is Lost

The climax of Act III is . . . the Climax

These are the major turning points of your story.

On the basic level, the relationship plotline is no different.

You will have a climactic turn in the relationship for each act (and two for Act II).

Recall that in a relationship turning point, the characters will either draw closer to each other or be pulled apart.

This often includes a moment of vulnerability that is either accepted or rejected (or in some cases, neglected) by the other character.

(Again, I'm not gonna repeat everything I said on relationship turning points, so please read about them in depth here.)

At these climactic moments, that's what's gonna happen.

There will be a significant (i.e. something that has deeply personal or far-reaching consequences) moment that results in being closer or more distant.

Mr. Darcy proposes to Elizabeth at the midpoint of Pride and Prejudice. This is a vulnerable move that Elizabeth rejects, pushing him further away. It's a major turn in the relationship, because their relationship can never truly go back to what it was previously.

It also sets us on a new course for the relationship for the next quarter of the story.

Anakin accepts that Obi-wan needs to die. This is a major turn in the relationship that pushes the characters further apart, putting them on a new course.

In 1984. Julia and Winston meet up for their first secret rendezvous and draw closer together. This sets them on a new course in Act II.

Because the relationship plotline fits between the internal and external plotlines (it's not as personal as the internal plotline but not as broad as the external plotline), it is often influenced by those plotlines. This may influence what those turning points look like.

For example, Anakin agrees Obi-wan must die because he has externally joined Palpatine and has internally stepped into the dark side.

In The X-Files, Mulder and Scully are most often distanced because of external forces (alien abduction, for example). And in Spider-man, Peter and his love interest are often pulled apart because of his internal conflicts (such as not wanting to put her in danger).

As I mentioned in my relationship plot series, essentially, at the basic level, there are two types of forces at work: one is pushing the characters together and the other is pulling them apart. This creates an ebb and flow, a zig-zag, a dance, in the relationship.

These forces can come from within a character.

Within the relationship itself (the characters want different things)

Or from external elements.

Act-level turning points push together or pull apart the characters in ways that can't truly be reversed.

Mapping the Push and Pull of Act-level Turning Points

After a significant turning point, the relationship can't go back to what it was previously.

This means, at the basic level, you have just four options for turning points:

Apart --> Close

Close --> Apart

Apart --> Further Apart

Close --> Closer

Some in the writing world say that each major turning point needs to flip to the opposite value (apart --> close OR close --> apart) and that you need to alter them for each turn.

So, if the midpoint moved the characters from apart --> close, then Plot Point 2 needs to move them from close --> apart.

This creates a zig-zag through the whole narrative arc.

You may be familiar with this concept if you've heard the idea that, if the midpoint is a victory, then Plot Point 2 needs to be a failure (Blake Snyder talks about this in Save the Cat!). Following that, the climax is then a victory. Zig-zag. + --> - --> +

This is a great rule of thumb, and you can see it play out in many relationship plots, particularly in romances. The characters are resistant to each other at Plot Point 1, are in love at the midpoint, break up at Plot Point 2, and get back together at the climax.

This back-and-forth zig-zag can be really effective.

But it's not the only option.

You can technically push close characters closer. And pull distant characters further apart.

It doesn't always need to be a zig-zag. It can be a zig-zigger or a zag-zagger 😉

For example . . .

In Revenge of the Sith, at Plot Point 1, Anakin and Obi-wan, who start close, are drawn closer simply by the fact Anakin saved Obi-wan's life. At the Midpoint, they are pulled apart by Anakin accepting Obi-wan needs to die. At Plot Point 2, they are pulled even further apart as they decide they may need to kill each other. At the climax, their relationship is ruined as Obi-wan leaves Anakin for dead.

So it looks like this:

Plot Point 1: close --> closer

Midpoint: close --> apart

Plot Point 2: apart --> further apart

Climax: apart --> further apart

In Monsters Inc. Sulley and Boo start as strangers and as she wreaks havoc in Monstropolis, Sulley wants to get rid of her (but the situation forces them physically together). At the midpoint, Sulley realizes that Boo isn't dangerous and cares for her. At Plot Point 2, Sulley scares Boo and then Waternoose physically separates them. At the climax, Boo overcomes her fear of Sulley and helps him. Together, they defeat the antagonists.

It looks like this:

Plot Point 1: apart --> further apart (just in the sense that Sulley wants to get rid of her)

Midpoint: apart --> close

Plot Point 2: close --> apart

Climax: apart --> close

Notice that each major turn starts with (essentially) the value of the previous turn. So really . . .

Revenge of the Sith: close --> close(r) --> apart --> (further) apart --> (further) apart

Monsters Inc.: apart --> (further) apart --> close --> apart --> close

This will be important in the next section.

But first, I want to acknowledge the fact I'm simplifying here. What is what may not always be obvious, because there are so many factors. Plot Point 1 in particular tends to be tricky because often the characters want to be apart but are forced together. Or, want to be close, but are forced apart. It can often appear to have both a push and a pull. This can make it harder to label. That's fine, just know what is happening and how.

You also may have one character wanting to draw close while the other wants to be apart--but still, usually the turn will end with the relationship either closer or further apart. Either the one succeeds in getting them closer together, or the other succeeds in pushing them apart. If your characters want different things and you get confused about who to focus on, focus on the protagonist.

And in some stories, particularly where the relationship plotline isn't a predominant plotline, the characters may simply be physically pushed together or pulled apart. (However, if there is a significant, emotional push and pull present, it's usually best to focus on that.)

Just map the turns to best serve your perspective of your story--this is meant to help your work, not hurt it.

Journeying Between Turning Points: The Dance

In relationship plotlines, just as with other plotlines, the turning points may be viewed as "destinations" and the space between those turning points as "journeys."

The turning points shift the trajectory of the plotline. This is like flying somewhere and having to take multiple planes. Each airport is a turning point--you head in a different direction (at least a slightly different direction) with each flight, until you get to the final destination (the final turning point). Once you board a plane, you can't go back to the airport--it's in the sky. There are no returns.

Between each act-level turning point is a flight, a journey.

And each journey has progress and setbacks.

Meaning, each journey has moments that push and pull the relationship.

This is what I think of as "the dance" (term courtesy of Romancing the Beat by Gwen Hayes).

The characters are dancing to the next turning point, and it's generally a three-step dance:

Two steps forward and one step back

Or

One step forward and two steps back

While this idea was originally intended for romance writers, Romancing the Beat has plenty of concepts you can borrow and adapt for other relationship arcs. The dance is a great way to look at the journey between turning points.

And both the journeys and the turning points keep the relationship from circling in the plotline. The audience doesn't want to feel like they have no clue where the plotline is going--they don't want to get dizzy trying to sort it out.

When you have a destination (turning point) and a journey (the dance of push and pull), the plotline has a direction. It might turn into a zig-zag, or a zig-zigger, or a zag-zagger 😉.

But it's still going in a direction.

While the turning points are a major shift (points of no return) . . .

. . . the journey is made up of small back-and-forth steps that aren't as dire.

Anakin and Obi-wan are close at the beginning of Act II, but cracks are starting to come between them. Because of this and Anakin's external and internal plotlines, it becomes, more or less, a one step forward, two steps back dance, until WHAM! At the midpoint, we need to make sure Obi-wan is dead! (For what it's worth, I feel like the film could have handled the dance better, so the jump didn't feel so drastic--and I think a lot of people feel like that film could have handled a lot of things better, but I think you get the point).

Likewise, after Mr. Darcy's proposal, Elizabeth engages in a two steps forward and one step back dance--falling for Mr. Darcy more and more. . . .

Generally, the idea is that if the dance is one step forward and two steps back, then the next turning point is a major shift that pulls the two apart. And if the dance is two steps forward and one step back, then the next major turning point is a major shift that pushes them together.

But this is just a metaphor, and all metaphors are imperfect.

While I think this is a good rule of thumb, I don't know that that is how I always see it in the wild. Sometimes one step forward and two steps back prepares us for a major shift that pulls the characters apart, but then the story actually delivers a major shift that pushes them together. It might be a little more shocking and disorienting, but it's still an option.

So don't get too rigid.

Let's be chefs, not cooks.

The idea is that there is a small ebb and flow on the journey. If it's helpful, you may think of these as mini turning points--scene-level turning points. Not as drastic, but still bringing the characters closer or pulling them apart, scene after scene after scene. Then we have a major turn at a destination.

The major turn sets us up for the next journey--the next quarter of the story. And the next dance starts.

Inciting Incidents: The Medium Turning Points

You've probably heard of the story's inciting incident.

Well, guess what?

It's a turning point.

It's the turning point that kicks off the plotline.

It's bigger than a scene-level turning point, but not as big as an act-level turning point.

Just as there is an inciting incident for the whole narrative arc, there are, arguably, inciting incidents for each act.

It's the medium-sized turn that kicks off the next journey. It's when the characters board the next plane. It's when the music starts and the characters get into position.

Returning to our ongoing Pride and Prejudice example . . .

At the midpoint, Darcy proposes to Elizabeth--this is a major turning point (specifically of Act II, Part I), and she turns him down:

Apart --> Further apart

Okay, so what gets Elizabeth to start thinking differently about Mr. Darcy?

It's his letter.

Mr. Darcy sends a vulnerable letter explaining himself to her. This leads Elizabeth to question her judgments of him.

The letter is the inciting incident of Act II, Part II--it kicks off the journey of Elizabeth's two steps forward and one step back dance . . . until she's completely fallen for him by Plot Point 2.

In Romancing the Beat, this (roughly) aligns with (or at least leads to) what Gwen Hayes calls "The Inkling." If the characters want to be apart, but will end up close at the next destination, then the inkling is one character (or both) thinking, Maybe we could be close . . .

Or, if the characters want to be close but will be pulled apart at the next destination, then the inkling is one character (or both) thinking, Maybe we should be apart . . .

Of course, you can use this approach with the other options as well. If the characters are apart, and end up more apart at the next destination, then the inkling is one character (or both) thinking, Maybe we should be further apart . . .

And if the characters are close and end up closer at the next destination, then the inkling is one character (or both) thinking, Maybe we could be closer . . .

Naturally, though, something leads to the character thinking this in the first place (inciting incident, more or less). It could be the other character. It could be an external force. It could be an internal force. It could be a vulnerable moment. It could be a letter from Mr. Darcy.

Whatever it is, it kicks off the next journey.

Elizabeth receives the letter (external information), which leads to the inkling . . . Maybe Mr. Darcy is better than I thought he was. . . .

And, just as a reminder . . . another way to look at the back-and-forth of the relationship is through the lens of trust vs. distrust. So, the character may think (on some level) . . . Maybe I can trust him. Or . . . Maybe I can't trust him. Or . . . Maybe I can trust him a bit more. Or . . . Maybe I should trust him a bit less.

At the beginning of the journey, the character may be resistant to the inkling (think: "Refusal of the Call" or "Debate"). Could Elizabeth have really misread Mr. Darcy so completely? It just can't be so! she thinks.

And with these principles in mind, you are ready to get more specific with structuring your relationship plotline . . . . just promise me you'll remember they are principles, not laws.

* Note: After writing this out, I just wanted to come back and add . . . in Save the Cat! Blake Snyder has a beat called "B Story" that he sees as the introduction of the central relationship. I think perhaps, from an abstract view, this is actually the (relationship plotline or B Story) inciting incident for Act II, Part I, but I'll need to ponder on that.

Mapping Relationship Plotlines with Specific Labels

At the beginning of this series, I mentioned you could get more specific with relationship arcs by labeling them in more specific terms. For example:

Strangers --> allies --> best friends

Enemies --> friends --> enemies

Strangers --> colleagues --> best friends --> lovers

Lovers --> exes --> lovers

Family --> strangers --> enemies

It's likely that each of these is separated by a significant turning point, with a journey in between.

For example, say we wanted to write a story like this:

Strangers --> Enemies --> Friends --> Exes --> Lovers

In the beginning, the characters are strangers who then meet and have to work together, but get the wrong first impression of one another, and they decide they totally hate each other by Plot Point 1. At the beginning of Act II, Part I, they have the inkling that maybe they can trust each other and make this work. They do a two steps forward and one step back dance. At the midpoint, they have a significant vulnerable moment that draws them together, and now? They're friends.

But at the beginning of Act II, Part II, they have the inkling that maybe they can't trust each other--maybe this friendship can't work. They do a one step forward and two steps back dance. At Plot Point 2 a vulnerable moment leads to a rejection and a break up. They separate, but have the inkling that . . . maybe they could have been more than friends . . . if they had handled things differently.

They do a two steps forward and one step back dance and at the climax, hit their most vulnerable moment--where they lay it all on the table and stand figuratively naked in front of each other. They love each other, and they both accept. They kiss and everything is happily ever after.

That's how many relationship plotlines go.

Your job will be to figure out the destinations, the boarding, and the (turbulent) flights for yours.

Make sure the biggest moments are the act-level turning points.

Next time, I'll cover some of the key beats you'll find in almost any relationship plotline (they just might be in a different order, based on your destinations).

Articles in this Series:

The 4 Basic Types of Relationship Arcs

Turning Relationship Arcs into Plots, Part 1

Turning Relationship Arcs into Plots, Part 2

Turning Relationship Arcs into Plots, Part 3

Structuring Your Relationship Plotline

Upcoming: Structuring Your Relationship Plotline, Part 2: Key Beats

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

That post that's like "stop writing characters who talk like they're trying to get a good grade in therapy" really blew the door wide open for me about how common it's become for a character's emotional intelligence to not be taken into consideration when writing conflict. I remember the first time I went to therapy I had such a hard time even identifying what I was feeling, let alone had the language to explain it to someone else. Of course there are plenty of people who've never been to therapy a day in their life who are in tune to their emotions. But even they would have some trouble expressing themselves sometimes. You have to take into account there are plenty of people who are uncomfortable expressing themselves and people who think they're not allowed to feel certain ways. It also makes for more interesting conflict to have characters with different levels of understanding.

89K notes

·

View notes

Text

Creating Likeable Characters

Sometimes it’s difficult to make your characters likeable as they are tested and are pushed to further and further lengths. Sometimes they have to make hard decisions, and sometimes the pressure gets to them and they mess up, hurt another character or an innocent bystander. How can you keep them likeable throughout the whole plotline?

- Keep their motivations pure.

It almost always comes back to the heart – if their heart is pure, and that’s established early-on, the audience is more likely to root for them.

- Give them flaws – make them human.

Not every character has to have some huge problem, like an addiction or a traumatic past or a disability – if your entire cast does, it’s no problem, but it’s not necessary. But every character has to have some flaw(s), whether it’s cheating at card games because he can’t stand to lose or being too-closed minded or closing off when she gets too emotional. If your character doesn’t have a flaw, they start to come off as too perfect, too angelic, pretentious.

- Give them permission to mess up.

This ties in with flaws – if your character is inclined to make a bad decision at any point in the plot, don’t steer him away from it because “oh no he’s my protagonist and he must be Good and Whole and Pure and All-Knowing”. Let him walk into that ambush despite the sick feeling in his stomach and get half his army killed; let her rush into a confrontation with a bully and get into a fight with another girl who has a switchblade. Let your characters mess up – it shows that they’re human.

- But if your character messes up, let them own up to it eventually.

The general who killed half his army by ignoring the unease in the back of his mind might cry over their makeshift graves long after the rest of the platoon is asleep; the girl sitting in the infirmary might feel remorse for knocking her opponent’s block off. Or your characters might argue and might be stubborn and might not apologize for weeks. But let them apologize eventually. This goes back to the heart, and what the character knows is right.

- Relationships with other characters are vital.

That’s not to say a loner character can’t be likeable – but the audience’s perception of a loner character is determined by the thoughts/words of other characters. Characters all color each other and define parts of each other, just like people do to each other in real life. If your character is a jerk to other characters and other characters don’t like him (especially if the characters who dislike him are likeable), the audience won’t like him either. The character’s image depends not just on himself, but on his supporting cast.

Hope this helps! - @authors-haven

7K notes

·

View notes

Note

I have an odd question. I have a character that needs to be easy to hate because of plot reasons but I also need her to be redeemable because part of the plot requires her growth. She's also crucial to the ending and saving the MC so I can't have her be too awful. How do you recommend finding the balance of that

?

Please read this post "Creating Likeable Characters" by authorshaven, and create your character accordingly. Introduce them by their flaws (e.g. their first scene they bully the MC), emphasize their flaws (e.g. they're regularly loud and rude), and show them making both good and bad decisions but focus on the bad (e.g. they bring a lovely homemade cake to the party, but they intentionally pour their drink on another guest).

Basically, write a likeable character who is also a hot mess. To paraphrase Kim from Freaks and Geeks "don't be mean, just be a b*tch." Your character can still have the best of intentions, and if given the chance to explain, is probably justified. Their "redemption" doesn't have to be a major personality change—though it can be—but can simply be the reader finally understanding their side of things and agreeing.

Depending on your setting, you choose what count as "easy to hate" flaws for this character. Once the draft is done, future drafts will help you develop this character's arc to have the exact balance you want.

—

+ Please review my pinned Ask Policy before sending in your ask. Thank you.

+ If you benefit from my updates and replies, please consider sending a little thank you and Buy Me A Coffee!

143 notes

·

View notes