Text

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

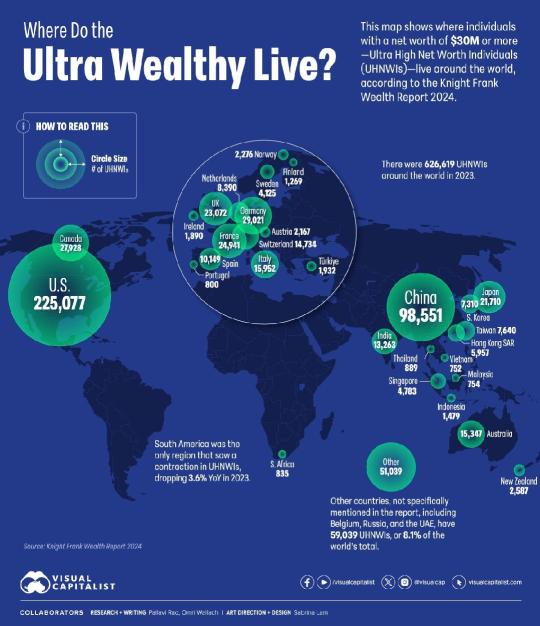

Where Do the Wealthiest People in the World Live?

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do not forget about West Papua.

Do not forget about the colonial genocide being committed against the indigenous West Papuans.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

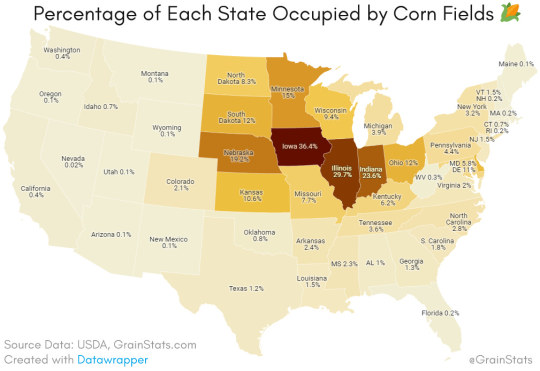

🌽🌽🌽

Percentage of Each State Occupied by Corn Fields

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Robot dogs armed with AI-aimed rifles undergo US Marines Special Ops evaluation https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2024/05/robot-dogs-armed-with-ai-targeting-rifles-undergo-us-marines-special-ops-evaluation/

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from the New York Times:

The lawn is dead. Long live the lawn. Lately this entrenched symbol of American domestic life — verdant, weed-free and crisply mowed — has come under wider scrutiny as a profligate relic, out of sync with an ecologically conscious era.

For many years, environmentalists have deplored conventional turf grass lawns as biodiversity dead zones that require billions of gallons of water every week in the United States, with outdoor irrigation accounting for a third of household water consumption on average nationwide, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. To say nothing of the polluting fertilizers and toxic pesticides and all the mowers belching greenhouse gases to keep those lawns lush and manicured.

“Lawns seem to draw as much irrational hate as they do love these days,” said Paul Robbins, dean of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the author of “Lawn People: How Grasses, Weeds, and Chemicals Make Us Who We Are.”

He added, “Green lawns, as much as brown ones, are now seen as a moral failing.”

But there is room for compromise. Even the most ardent proponents of sustainable, ecologically mindful landscaping argue that a simplistic “lawns are evil” narrative is unhelpful.

Edwina von Gal, a landscape designer in East Hampton, N.Y., who founded the Perfect Earth Project a decade ago to promote toxin-free, biodiverse gardens, emphasizes that lawns are not inherently negative.

“There’s nothing else like lawn for playing with your kids or your dog or a Frisbee,” she said. “But I always ask people to think about how much lawn they need. How far can you throw a Frisbee?”

Her philosophy: “Think of a lawn as more of a function than a fashion, because the fashion is changing.”

A growing number of Americans are scaling back their grass lawns or doing away with them entirely, especially in drought-affected parts of the West, where some states and municipalities have implemented restrictions on new lawns and on irrigation as well as offering financial incentives to replace existing lawns with low-water landscapes.

“Really you have to look at lawns as reservoirs, given the amount of water it takes to care for them,” said Charlie Ray, founder of the Green Room, a landscape architecture firm in Phoenix. “We are trying to reframe the conversation of what is beauty and what is lush-feeling. When you see these huge, incredibly water-intensive lawns, is that really what high-end looks like?”

Even in the desert, it is possible to create seasonal landscapes that feel lush, using native, “water wise” plant material, he said. And a bit of functional lawn can absolutely be a part of that.

Just how much lawn depends on factors that include local climate and ecology. A general rule of thumb suggested by Ms. von Gal is two-thirds for the birds. “The science shows that if you have roughly 70 percent natives, you’re going to be able to support a healthy bird population, and they’re the key indicator species for environmental health,” she said.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was an active docent and volunteer in the desert, and hiked all over the place, whenever I spotted the remains of a mylar balloon, I went for it, shoved it in my backpack and brought it back to properly dispose of it. Those things are vicious killers of wildlife.

Excerpt from this story from the New York Times:

Balloons released in the sky don’t go to heaven. They often end up in oceans and waterways, where they’re 32 times more likely to kill seabirds than other types of plastic debris. Despite this, humans like to release them en masse, be it to celebrate a loved one’s life or a wedding, or to reveal the gender of a baby.

The practice is on the verge of becoming illegal in Florida, where the legislature has joined a growing number of states to ban the intentional release of balloons outdoors. The Florida ban is expected to be signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis and would take effect July 1.

Florida is at the forefront of a dizzying and contentious array of statewide bans, outlawing lab grown meat, certain books from school libraries and classrooms, and most abortions after six weeks. But the balloon ban is rare for garnering widespread bipartisan support. It was championed by environmentalists and sponsored by two Republican lawmakers from the Tampa Bay area, Linda Chaney, a state representative and Nick DiCeglie, a state senator.

“Balloons contribute to the increase in microplastic pollution which is harmful to every living thing including humans, polluting our air and drinking water,” Ms. Chaney wrote in an email.

“My hope is that this bill changes the culture, making people more aware of litter in general, including balloons,” she said.

Ms. Chaney said she first heard about the perils of balloon debris in 2020. Aquatic animals often mistake balloons for jellyfish and feel full after eating them, essentially starving from the inside out. Ribbons affixed to balloons entangle turtles and manatees. Balloons also pose a threat to land animals. In her research, Ms. Chaney learned about a pregnant cow that died after ingesting a balloon while grazing. The unborn calf died too.

The bill closes a loophole in an existing Florida law that allowed for the outdoor release of up to nine balloons per person in any 24-hour period, a provision that critics say didn’t achieve the goal of reducing marine trash.

The new legislation makes it clear that balloons can pose an environmental hazard, supporters say. It equates intentionally releasing a balloon filled with a gas lighter than air with littering, a noncriminal offense that carries a fine of $150. The ban also applies to outdoor releases of any balloons described by manufacturers as biodegradable.

The ban does not restrict the sale of balloons by party suppliers or manufacturers; they could still be used indoors or as decorations outdoors if properly secured.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from the New York Times:

Several large-scale, human-driven changes to the planet — including climate change, the loss of biodiversity and the spread of invasive species — are making infectious diseases more dangerous to people, animals and plants, according to a new study.

Scientists have documented these effects before in more targeted studies that have focused on specific diseases and ecosystems. For instance, they have found that a warming climate may be helping malaria expand in Africa and that a decline in wildlife diversity may be boosting Lyme disease cases in North America.

But the new research, a meta-analysis of nearly 1,000 previous studies, suggests that these patterns are relatively consistent around the globe and across the tree of life.

“It’s a big step forward in the science,” said Colin Carlson, a biologist at Georgetown University, who was not an author of the new analysis. “This paper is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that I think has been published that shows how important it is health systems start getting ready to exist in a world with climate change, with biodiversity loss.”

In what is likely to come as a more surprising finding, the researchers also found that urbanization decreased the risk of infectious disease.

The new analysis, which was published in Nature on Wednesday, focused on five “global change drivers” that are altering ecosystems across the planet: biodiversity change, climate change, chemical pollution, the introduction of nonnative species and habitat loss or change.

The researchers compiled data from scientific papers that examined how at least one of these factors affected various infectious-disease outcomes, such as severity or prevalence. The final data set included nearly 3,000 observations on disease risks for humans, animals and plants on every continent except for Antarctica.

The researchers found that, across the board, four of the five trends they studied — biodiversity change, the introduction of new species, climate change and chemical pollution — tended to increase disease risk.

“It means that we’re likely picking up general biological patterns,” said Jason Rohr, an infectious disease ecologist at the University of Notre Dame and senior author of the study. “It suggests that there are similar sorts of mechanisms and processes that are likely occurring in plants, animals and humans.”

The loss of biodiversity played an especially large role in driving up disease risk, the researchers found. Many scientists have posited that biodiversity can protect against disease through a phenomenon known as the dilution effect.

The theory holds that parasites and pathogens, which rely on having abundant hosts in order to survive, will evolve to favor species that are common, rather than those that are rare, Dr. Rohr said. And as biodiversity declines, rare species tend to disappear first. “That means that the species that remain are the competent ones, the ones that are really good at transmitting disease,” he said.

Lyme disease is one oft-cited example. White-footed mice, which are the primary reservoir for the disease, have become more dominant on the landscape, as other rarer mammals have disappeared, Dr. Rohr said. That shift may partly explain why Lyme disease rates have risen in the United States. (The extent to which the dilution effect contributes to Lyme disease risk has been the subject of debate, and other factors, including climate change, are likely to be at play as well.)

26 notes

·

View notes