Text

WEEK 11: Looking at Mana Wahine and Decolonisation

Traditional Māori and Western cultural perceptions of women and their roles in society contrast dramatically. The Māori world view is complex and interwoven, ideas regarding women are centred around the concept of mana wahine. The English langue has deficiencies in articulating the concept of mana wahine. To label mana wahine as “Māori feminism” is an over simplification. Mana wahine is distinct from Pākehā feminism as they are oppressed not just by the patriarchy but also by ‘race’. It is “problematic” to lump them under the same category. It is a “uniquely Māori way of explaining and relating to the world” (Simmonds, 12), centred on knowledge and the mana of the women. It has a more spiritual dimension and significance compared to secular Pākehā feminism which has been labelled as “spiritually impoverished”(Simmonds, 15).

Mana wahine is deeply inter-connected with other parts of cosmological Māori culture. Pre-colonialism there was no arbitrary hierarchy of sexes as evidenced by gender neutral pronouns (Mikare, 1). Men and women were closely linked, carrying out complementary roles in society. Simmonds argues that it was normal for women to fill a wide variety of roles in leadership and that misconceptions of Māori women as passive to men are due to “colonial paternalism” (Simmonds, 14). Māori women had independent agency for self-determination and liberal expression of sexuality. Women were acknowledged as having a vital role, for example the “words such as Whare Tangata, which can mean house of humanity but also womb.” (Simmonds 15). This gives them the rightful acknowledgment and respect they deserve.

Simmonds advocates the incorporation of mana wahine into the mainstream academic realm as an epistemological framework.

In the western colonial mindset of the Victorian era women were considered second class citizens or worse, mere chattels to be confined to domestic activities and fully subservient to a dominant male family leader. They were seen as objects to be owned. This was justified using a dubious interpretation of Christian dogma of social hierarchy (Simmonds 15). This is a deeply engrained ideology that’s persists today in derivative forms. When imposed upon the Māori it caused fragmentation of the transmission of inter-generational knowledge and mana wahine, having devastating effects on future generations leading to the isolation and marginalisation of Māori women.

References:

Simmons, Naomi. “Mana wahine: Decolonising politics.”, Women’s Studies Journal, 25.2 (2011): 11-25. Print.

Mikaere, Annie. “Māori Women: Caught in the Contradictions of a Colonised Reality.” Waikato Law Review, 2.1 (2014): 1-9. Print.

0 notes

Text

WEEK 10: Appropriation and exploitation in Aotearoa

Swarzpaul identifies how Māori and other indigenous cultures have had prominent aspects appropriated for misuse by external parties. Big companies do it purely for profit, thinking that by giving their characters “Māori-esqe” characteristics makes them look “badass” (Swarzpaul 1) and the player by extension. The player wants to be put in their shoes in order to carry out their violent fantasies and misinformed idea of what being native is like. By drawing from multiple cultures and taking their signifiers out of their intended context this has a homogenising effect on the cultures bundling them together as undistinctive exotic others. As seen in The Mark of Kri, the protagonist was an idealised conglomeration of indigenous cultures. The makers drawing for the idea of the fearsome native warrior and savage brutality with no real appreciation of where the elements of the culture came from.

Swarzpaul states that because the western man has become “civilised” they have lost their inner “wild-man” (Swarzpaul 2). Therefore they try to taste of some lost exoticism by sampling from rarefied indigenous cultures. With no payment and no consultation this transpires into cultural appropriation and exploitation. He does not take issue with outsiders partaking in the culture they simply must be genuine and want to engage in sincere dialogue and learn about the culture.

References:

Engels Schwarzpaul, Tina “Dislocating William and Rau: The Wild Man in Virtual Worlds”. School of Art and Design, AUT University. n.d

0 notes

Text

WEEK 9: Art, Design, and Asian heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand

(I could not attend the field trip as I was in hospital. Documentation available.)

The everyday meaning of the word hybridity simply means a mixing of two or more things.

However, Bhabha expresses that his theory of hybridity is somewhat more complicated and nuanced when it comes to talking about people. Cultural hybrids are completely different to their constitutive parental cultures and can never fully identify with one root alone. He redefines this as “a third space” (Rutherford 204), a quite unique vantage point and human experience from which to operate, emerging from between two or more cultures. The hybrid culture that emerges is in ongoing a state of flux, constantly morphing and changing. This facilitates a ripe ground for new ideas to emerge which is essential to avoiding the stagnation of a culture. Our western culture clings to binary ideas of black and white, when in reality this is rarely the case. Hybridity is at work in every culture and in the evermore interconnected age of globalisation different cultures are coming into contact now more than ever before. Hybridity’s dynamic interplay of ideas allows us “to rethink them and extended them”(Rutherford 216 ).

References:

Rutherford, Jonathan and Homi Bhabha. 1990. The Third Space. Interview with Homi Bhabha. In: Ders. (Hg): Identity: Community, Culture, Difference. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 207-221.

0 notes

Text

WEEK 8: Stereotypes and Speaking Back to New Zealand’s Dominant Culture

Wall’s article shows how the generalised stereotypes of Māori perpetuated by the media today are derivatives of more sinister colonial caricatures born out of the Eurocentric assumption of intellectual and moral superiority. She identifies four main categories that Māori have been socially subjugated to conform to, having a subconscious dehumanising and demeaning effect (Wall, 41).

Nisbet, Al. Digital Cartoon. Marlborough Express 2010 May 29 2013 Web.

This work by Al Nesbit, a Pākehā illustrator, published in the Marlborough Express during political discussion about providing meals for children in low decile schools.

It portrays grossly rotund Māori adults posing as school children to exploit the system.

They are little more than caricatures, while the Caucasian students appear innocent and afraid of the overbearing personalities, a stigmatisation relating to fear of “the black other” (Wall, 40). This reinforces the stereotype of Māori as the “social deviant” (Wall, 42) an auxiliary type of the comic other with a disposition of innate laziness and criminality. Nesbit said he was glad to have received a reaction form the public saying people should “lighten up”. However, there was widespread condemnation that he crossed the line between satire and racism.

Boy. Dir. Taika Waititi. New Zealand Film Commission, 2010. Film

The film ‘Boy’ by Taika Waititi is a representation of Māori by Maori. Waititi is a master of “Happy sad cinema”. He utilises his distinct directorial style to play to some aspects of these stereotypes to a comedic effect while juxtaposing them within sobering social issues making a strong social commentary about New Zealand society. He uses almost all the main stereotypical character tropes Wall identified in a way that reveals a very human story which in fact challenge the assumptions of the dominant culture. He highlights the emotional complexities of human beings, and that their multifaceted nature that cannot be confined to basic stereotypes.

References:

Wall, Melanie. “Stereotypical Constructions of the Māori ‘Race’ in the Media.” New Zealand Geographer 53.2 (1997):40 – 45. Print

Dally, Joelle. “’Racist’ cartoon slammed.” Stuff 30 May. 201

0 notes

Text

WEEK 7: Postcard Series: Framing 'The Exotic'

Hau’ofa notes that Pacific identities are problematic to define because the Pacific is such a vast area, encompassing numerous diverse and distinctive people groups. He touches on the difficulties of the past in forming a unified Pacific identity which resulted in an ineffective global voice making them susceptible to exploitation by western powers.

He also points out that some of the difficulties encountered are also of their own making. The strong sense of individual nationalism and exclusivity between some ethnic groups has created division. He condemns such lines of thought which continue to perpetuate stereotypical prescribed traits and behaviours as ‘being racist, callously totalitarian, and stupid.’ (Hauofa 406). He advocates that by looking to the ocean as the unifying factor, pacific peoples could come together to advance collective interests so as not to become “dispensable and forgotten”(Hau’ofa 393) in the march of globalisation.

Wendt touches on how Pacific identities have been pacified by the institutionalised mechanisms of Western colonialism socially, politically, spiritually and educationally. Their original cultures were viewed by Europeans as little more than “Darkness, superstition, barbarism and savagery.”(Wendt 15) for which they need to be “Christianised”, subdued and “civilised.”

Wendt states that Pacific peoples must first confront and come to terms with their colonial past in order to see a way into the future. He identifies education as being fundamental to “nation building” (Wendt 15) of the islands. However, he argues that the engrained colonial education system of the past has been used simply as a mechanism of “whiteification” (Wendt 16) which has had a “lobotomising” (Wendt 16) effect on the psyche of subjugated people groups. He contends that it was not designed for the islanders to excel but rather to become little more than “minor and inexpensive cogs... for the administrative machine.”

There is hope in their identity being formulated by expression thorough traditional and contemporary art and the rise of promising native literary figures. Allowing pacific peoples to write their story themselves.

References:

Hau’ofa, Epeli. “The Ocean in Us.” The Contemporary Pacific 10.2 (1998): 391-410. Print

Wendt, Albert. “Towards a new Oceania” in Sharrad, Paul. “Readings in Pacific Literature”. New Literatures Research Centre University of Wollongong, 1993.

0 notes

Text

Final Blogpost - Henimihi

This is a peculiar sight. A traditional Maori whare with a thatched roof residing in a quaint English country garden. It was made in New Zealand during the colonization boom. The treaty of Waitangi had been signed in 1840 and the country was under British rule. It was a time of great change for the Maori and their place as a people. A steady stream European tourists from all over the world travelled to experience the cultural and natural wonder of the central North Island. Tourism has long shaped interactions and perceptions of Maori (Bruke 18). Hinemihi was built in 1880 as a meeting house to show tourists traditional Maori life. During the eruption of Mt Tarewera in 1886 it sheltered about fifty people, the only building left standing in the town of Te Wairoa. Six years later it was bought for just Fifty pounds by Lord Onslow as a souvenir of his time spent in New Zealand. This however is a contentious and dubious exchange. The son of the original builder thought at the time that it was being sold to “the government” (Gallop 96), not a private overseas owner. The building was treated as an oddity and was used for a range of mundane uses. It was even considered as being a nightclub at one stage, sadly many other indigenous buildings displaced to foreign lands have suffered such a fate. (Schwarzpaul 46)

But for the Maori a whare is more than a physical building of wood, flax and paint. In Hinemihi’s case it represents a distinguished woman chieftain, one of the very few whare built with such a name. It is a living being that requires the respect and love that entails its intangible yet sentient life (Higgens 47). The building has life and feeling. The carvings have especially high value and display the fabric of Maori culture.

This image was taken when Hinemihi was restored, its thatched roof part of the mingling of the two cultures. For a time, it became a symbolic and spiritual meeting place for Maori in England. However, the future of Hinemihi is now at uncertain after a devastating fire at Clandon Park. The relationship between the expatriate Maori and Clandon park has become strained as what is left of the original structure and carvings now lie in storage. This raises some difficult ethical issues. The cost to rebuild Henemishi is immense. The jury is still out on whether Henemihi should stay in a foreign land and serve its people there or come back to its homeland. But this then raises even more issues such as where would it be put and who has rightful authority over it. Also, how much, if any, contemporary Maori art and design should influence its future appearance.

Hinemihi is a symbol of the unique relationship between that two counties a coming together of peoples. She has seen a lot of change in her life, a symbol not just of times past but also of the ongoing relationship between two very different cultures. Hopefully she can continue this role into the future in a respectable state.

References:

Alan Gallop, The house with the golden Eyes, Running horse Books, 1998, Print.

Bruke, G, Cultural Safety, Wellington, Wellington City Gallary, 1995, Print.

Engels-Schwarzpaul, “Take me away… in Search of Original Dwelling.” A Journal of Architecture and Related Arts, Vol. 10, 2005, 42-51, Print.

Higgins, R., & Moorfeild, J., Ngā tikanga o te marae. In Kit e Whaiao: An Introduction to Māori Culture and Society. Auckland, Pearson Education New Zealand Limited, 2004

0 notes

Text

Response to Take me away… In Search of Original Dwelling (100 words)

The aim of this reading was to show the absurdity of the modern western hunt to experience a vicarious sense of a fabled authenticity.

Icons of indigenous societies material culture which hold deep meaning and cultural significance have been appropriated and fashioned into tacky idealisations for exploitation and economic gain of big business or the people themselves.

The writer infers that most outsiders do not truly care for the culture itself - just what they can take away from it. For the exhibitioners, it was a supposed affirmation of cultural superiority. For the tourists, it was a temporary taste-test, a be-there-done that.

I think it’s like seeing a flower and trampling on it to get a better look.

0 notes

Text

Blogpost 4

Bells message is that all colonial art is made purposefully or subconsciously to support colonial aspirations and ideologies. This is a tourist poster made in 1935 targeted towards Europeans in England, Canada and Australia. It showcases some of New Zealand’s natural attractions as well as a beautiful smiling Maori woman in traditional dress being the dominant focal point. It’s an inviting picture which almost commoditises her as just another attraction, playing on the idea of the savage romantic. This idealisation of the Maori was engrained in the Pakeha artists early on to portray “a stern grandeur, or the romantic glow of a primitive state of existence might be imparted to some works of art.” (Bell, 142) The woman’s welcoming smile masks the hard truth. That Maori were outsiders in their own land mostly living poverty due to historical grievances.

To the European eye New Zealand is a “wonderland” a place for them to come and enjoy, to seek out the romantic in the indigenous culture as something of curiosity and entertaining spectacle. The chateau in the background looks grand and lavish, a transplanting of style from the continent meaning they can enjoy the wild and exotic from the comfort of familiar surroundings. This poster achieves its purpose, New Zealand looks like a wonderland – but what is life truly like for the native peoples. This work helps to reinforce the idea of the harmonious 100% pure New Zealand, masking the painful and largely unresolved injustice of the past.

References:

Laugesen, Carl, Wonderland of the Pacific, Chromolithograph,Cantabury Muesem, Christichurch 1935

Bell, Leonard. “The Representation of the Maori by European Artists in New Zealand, ca. 1890-1914”. Art Journal, Vol. 49, No. 2, Depictions of the Dispossessed (Summer, 1990), pp. 142-149

0 notes

Text

Blogpost 3 Tauiwi

Chapter 5 Tauiwi was a disconcerting read. I was never taught the full story of the colonisation of New Zealand and how the major events influenced each other. Till now I simply did not comprehend the full significance of the treaty of Waitangi. I had never read the translation of the Maori version nor fully understood what the treaty represented. Growing up I assumed it was just a peace deal, we have a public holiday for it after all. The most shocking thing that stood out for me was the apparent deficiency of the translation offered to the Maori signatories. Walker argues that by “…translating sovereignty as kawanatanga (governance) instead of the word mana, which was used in the 1835 declaration of independence. The word kawanatanga did not convey to the Maori a precise definition of the word sovereignty.” (Walker 91) The fundamental principle of a valid agreement is that both parties must fully understand what it is that they are agreeing on especially something as important as sovereignty. Unfortunately, the Maori language is very different to English and at times there are no neat translations. Some words are fraught with ambiguity and there is room for genuine mistake and misunderstanding. However, Walker suggests that the translators though supposedly “men of God” had vested interest in the passing of the treaty so the choice of words may have been indented to mislead. This action has defined our nation and has had centuries of ramifications. I can now appreciate the contention surrounding the treaty.

References: Walker, Ranginui, Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou – Struggle Without End, Auckland:Penguin, 1990, Book

0 notes

Text

Blogpost 2 Mātauranga and Kaupapa Māori

Mātauranga Maori is an ancient body of traditional knowledge with its basis in the home islands of Polynesia. Unlike the western framework this is a dynamic body of knowledge and way of framing thought that changes over time. One of its distinctions is that It does not suggest physical action. It addresses the fundamental metaphysical notions of identify, comprehension of time and space.

Kaupapa Maori on the other hand is focused on the “plan of action” (Royal 30). It is purposeful and its goal is to enhance Maori culture and thinking in our contemporary multi-culture context. It also allows the space for expression of Mātauragna Maori, liberating it from the strict bounds of western parameters. Its goal is more than just having Maori as an obligatory formality. Rather, going beyond a token gesture and really take Maori worldview and ways of thought seriously to find that there is new and complementary knowledge to be gained. Some of the clearest examples of Matāuranga Maori and Kaupapa Maori is the rich visual culture of carving and graphic design. However, such mays of thinking should not be shoehorned into only the arts. The point of using these modes of thinking is to give expression to transformative idea which may impact on all aspects of life.

Reference:

Royal, Charles. “Politics and knowledge: Kaupapa Maori and matauranga Maori.” Vol 47. No. 2, (2012): 30-39. Print

0 notes

Text

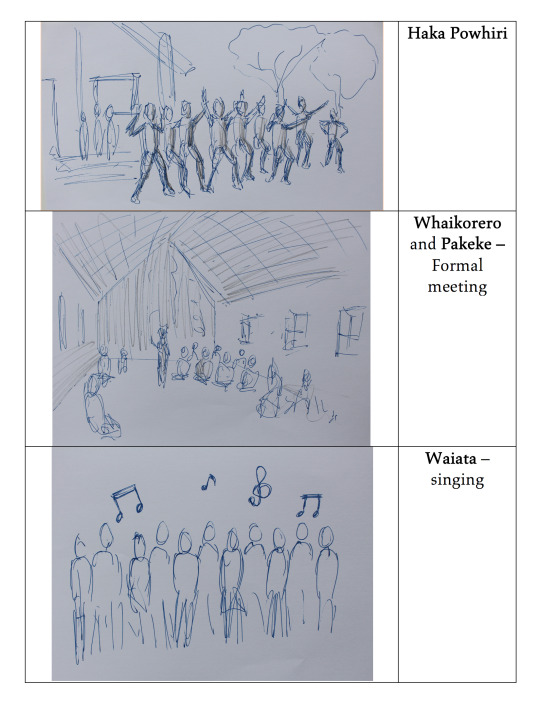

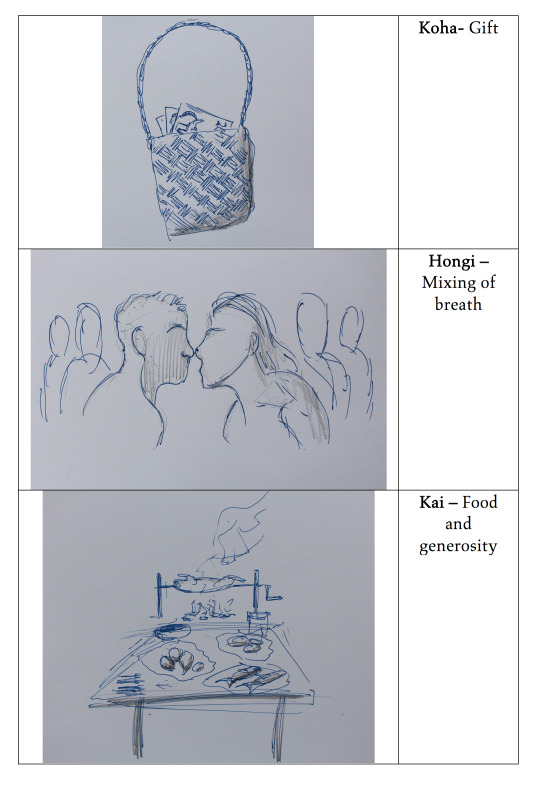

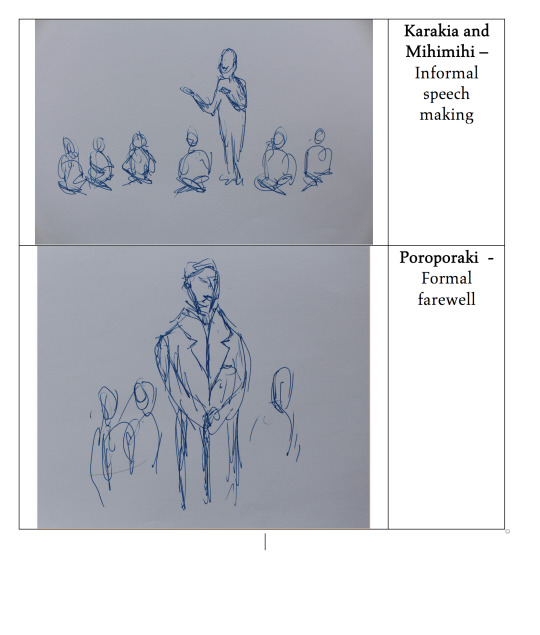

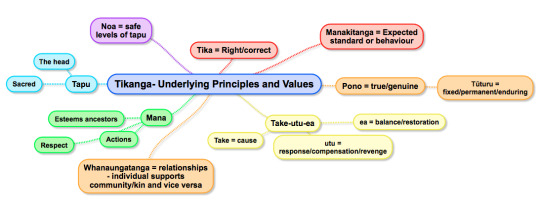

Blogpost 1 - Pōwhiri

Response to Hiring Moko Meads”Nga puttee o te tikmanga” Week 2 reading

The aim of this text was to briefly explore and explain some of the fundamental principles and values that govern Maori cultural practices and worldview. Understanding these concepts helps to explain the reasons for some everyday Maori customs and actions in the past that may have seemed strange or illogical to Europeans. These principles and values are all interrelated and based around maintaining social order and relationships as well as conflict resolution. This is done by all members of the society aspiring to reach particular standards and following specific protocols. Mead notes that Mana is one of the most important concepts in Maori social structure. It denotes one’s status and respect that should then be shown to them. In the past it also had a spiritual connotation relating to their connection to their gods. Mana is gained by the actions of the individual to prove their worth as well as being drawn from esteemed ancestors from the past. For example, a respected chieftain or a skilled orator are usually said to have a large amount of mana. However, Mead also states that “…interpersonal relationships are not a level playing field. They are much more complicated to manage because of other variables” (30), like in the case where older siblings will always have a higher social standing than younger siblings.

Mead, Hirini. Tikanga Maori, Living by Maori Values, Wellington, HUIA Publishers, 2003, Paperback

0 notes