Text

A VERY EXPENSIVE “TOUCH OR CARESS WITH THE LIPS”

THE DANGER FOR EMPLOYERS OF OMITTING TO ACT TIMEOUSLY AND DECISIVELY AGAINST SEXUAL HARASSMENT OFFENDERS

Note: This case, as reported, is 110 pages long. I will attempt to meaningfully summarise it to be much shorter. The overview of the facts is quoted verbatim as reported.

Introduction:

In the matter between P[…]-A[…] E[…] (Plaintiff)(private details of some of the parties & witnesses withheld in compliance with the law) and DR BEYERS NAUDE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY (First Defendant) and XOLA VINCENT JACK (Second Defendant), the High Court of South Africa, (Eastern Cape Division) awarded damages to the Plaintiff amounting to R3,9 million after she had been sexually harassed by her boss. The award was made against the first (employer) and second defendants (her Manager) jointly and severally.

After plaintiff’s employer had made her employment intolerable compelling her to resign, rather than pursue the conventional remedy of claiming an unfair constructive dismissal as provided for in the Labour Relations Act No. 66 of 1995 (“the LRA”), the Plaintiff elected to prosecute a claim sourced in the common law and contended that she had been the victim of a civil wrong, i.e. a delict.

The matter took more than ten years to finalise, amongst other, because of postponements and the fact that separate trials had to be held to first determine liability and thereafter to determine the quantum of damages.

Facts of the matter:

The Court summarized an overview of the facts of the matter as follows:

E[…] was employed at the Jansenville offices of the Municipality. Jack was her immediate superior. Although Jack was stationed in Klipplaat (approximately 20 kilometers from Jansenville) the two were often required to work together and Jack spent much of his time at Jansenville. On E[…]’s evidence she had enjoyed a good working relationship with Jack.

On 16 November 2009 E[…] was sexually assaulted by Jack. Shortly before the assault, there was some tension in the working relationship when E[…] refused to perform a task requested of her by Jack because she was of the view that the instruction fell outside of her job description. There was also an incident where Jack had conveyed to E[…] that if they did something together nobody would know. E[…] was uncertain as to what Jack had intended by this comment but stated that whatever his intentions were, she was of the view that they were not good.

This Court described the assault in the following terms:

“On Monday morning, 16 November, plaintiff was alone in her office when second defendant entered. After greeting her he walked directly to where she was sitting at her desk. As she looked up he bent down with his head over hers and, putting his mouth over hers, attempted to force his tongue into her mouth. She clenched her teeth and tried unsuccessfully to push him away. After a minute or so he desisted, leaving her with a mouthful of his saliva. She immediately wiped the saliva off her mouth. He then also tried to wipe her mouth with his hand but she knocked it away. He then mumbled something which she could not hear and then told her to make copies of certain items from a council agenda. Before leaving her office he told her that he was going to get a cold sore the next day because he had kissed her.”

The assault, and the manner in which it was subsequently addressed internally by the Municipality, culminated in [E[…]] resigning from the Municipality with effect from November 2010. Importantly so, it was found in the first judgment that E[…] had been compelled to resign, the Court concluding that “… [E[…]] has been forced to resign because of her Post Traumatic Stress Disorder [occasioned by the assault]”.

Actions taken by the Municipality:

According to the Municipal Manager at the time, one Mnyimba, the assault had come as a shock to the Municipality because the Municipality was a close-knit organisation akin to “a family” and it had not encountered an event of that kind before. There was no evidence that the Municipality had in place a sexual harassment policy as required by law at the time that the assault occurred which meant that the Municipality had no direction or clarity as to the rights of an employee who has reported an incident of sexual harassment and what assistance was available to her. There were also no procedures in place either in respect of the alleged victim or the alleged perpetrator and no disciplinary sanctions were stipulated to be imposed in the event that an employee was to be found guilty of sexual harassment.

By its own admission, the Municipality relied heavily on the advice of its legal advisor as to how to address the incident. As will appear from what is set out below, it was ill-equipped to manage the situation.

After the assault it would seem that a degree of panic set in and a distraught E[…] was placed on what was termed “special leave” for 2 days whilst the Municipality pondered as to what procedure should be followed in dealing with Jack who remained in the workplace. E[…] was informed that she was required to be back at work by Friday of the same week. Although she was clearly traumatized by what had happened to her, she was, extraordinarily so, instructed to communicate with Jack and to inform him that she would be absent from work for 2 days. She performed this task by sending him an SMS message. Whilst she was on this special leave Jack telephoned her enquiring, in reproachful vein, as to why she was not at work. She responded by informing him that she was sick and Jack in turn responded by stating that she did not sound sick. She offered to furnish him with a sick certificate. He also asked her where the key to her office was. After the conversation Erasmus trembled and burst into tears.

Thus the woman, whose personhood and dignity had only two days earlier been so egregiously violated by her male superior who was unable to control his base sexual urges, found herself in the humiliating and degrading position where she had to account to her assailant and where her assailant was seeking to reinforce his control over her by cynically interrogating the reasons for her absence in what I regard as a show of toxic masculinity exacerbated by the power imbalance between the two.

On 19 November 2009 a letter, in the name of Mnyimba, was transmitted to Jack affording him an opportunity to make representations as to why he should not be suspended in the light of the allegations which had been made against him by E[…]. On 23 November 2009 Jack replied in a letter offering no basis as to why he should not be suspended other than to baldly deny the allegation, in his words “… with the contempt it deserve (sic).” The Municipality, again apparently on legal advice, took a decision not to suspend Jack. No satisfactory reasons were furnished for this decision. When questioned about it, the refrain from the Municipality was that Jack also had rights and it did not want to infringe those rights or to create an impression of bias towards E[…].

Looking at the matter objectively and giving proper consideration to the gravity of the allegation made by E[…] as well as the circumstance that Jack was her superior and the Corporate Services Manager, it is difficult to understand the decision of the Municipality not to suspend Jack. Leaving aside the circumstance that there was an obligation on the Municipality to take steps to protect E[…], a suspension at that stage would after all have been no more than a precautionary measure so as to allow an investigation to take place and not a pronouncement of guilt. There is a perverse irony where the victim is instructed, albeit for a short time, to leave the workplace whilst the perpetrator remained in his position.

The Municipality elected instead to transmit, on 1 December 2009, a letter to Jack in terms of which he was instructed, pending the finalization of an investigation into the allegations, to remain at the Klipplaat office and not to have any contact with E[…]. When E[…] testified at the trial on liability it was put to her that the effect of the letter was to “banish” Jack to Klipplaat. It is however clear from the evidence that this is not what happened. The Municipality was not able to ensure that Jack did not have contact with E[…] prior to the holding of the disciplinary hearing. Jack would arrive at the Jansenville offices, often unannounced, and E[…] would either find herself in the presence of Jack or in earshot of him. Her reaction on these occasions and when she became aware that Jack was in the vicinity, was to lock her door.

Although E[…] complained about the conduct of Jack and the circumstance that he had breached the instruction to remain at Klipplaat, the Municipality did not reconsider his suspension nor did it take disciplinary action against him for what was, on the face of it, insubordination which was gross in that it was persistent and willful. This conduct of Jack may well also have amounted to victimization and retaliation.

More than three months lapsed before Jack was charged on 19 February 2010 with “gross misconduct” in terms of which it was alleged that he had “… forced himself upon a female subordinate [E[…]] and attempted to kiss [her] against her will”. In the first judgment it was astutely observed that the description of the misconduct of Jack as an attempt to “kiss” E[…] was an unjust mischaracterisation, the Court commenting as follows:

“…

It is necessary to point out that the presiding officer misdirected himself in stating that the second defendant had

“attempted to kiss”

the plaintiff. The evidence was that he bent over her and attempted to force his tongue into her mouth, only being thwarted because she clenched her teeth together.

“Kiss”

is defined in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary as

“a touch or caress with the lips as a sign of love, affection or greeting”

,

something very far removed from the sexual assault perpetrated upon plaintiff by second defendant.”

The disciplinary proceedings did not seem to have been a priority for the Municipality and the hearing was eventually held on 11 May 2010, half a year after the assault. Although Jack had strenuously denied guilt in his letter, he, without explanation, did not testify. He took a spurious technical point about the date of the assault. Unsurprisingly, he was found guilty of the charge which was preferred against him. The Presiding Officer found, correctly so, that “… the relationship between employer and employee is irretrievably broken down due to the seriousness of the allegations”. That however is where any commendation for the Presiding Officer’s decision ends.

The Presiding Officer then proceeded to mention, in his finding, something about the need to uplift the skills of employees, inexplicably utilizing this concern as a basis for not imposing a sanction of dismissal. The Presiding Officer found that a suitable sanction would be for Jack to be suspended without pay for a two-week period. To crown it all, the Presiding Officer recorded that the only reason why he did not give Jack a final written warning (as opposed to the short period of suspension without pay) was that Jack was already on a final written warning for theft, and in this context the evidence was that Jack had stolen a tank from the Municipality.

The decision by the Presiding Officer not to impose a sanction of dismissal was mindboggling given the character of the offence, the circumstance that Jack, the Corporate Services Manager, had abused his position of authority by assaulting a female subordinate who was in a particularly vulnerable position in that she was a temporary employee at the time that the assault occurred. Furthermore, Jack did not demonstrate any remorse, remaining defiant to the end. Where an employee has been found guilty of gross misconduct and fails to take the first step towards rehabilitation by acknowledging his wrongdoing, there can be little scope for corrective or progressive discipline.

The Municipality, as an Organ of State, was not only entitled, but in fact obliged given the obligations on it in terms of Section 195 of the Constitution, to have challenged the disciplinary finding which, on the face of it, was indefensible. It was obliged to have done so, inter alia, as part of its duty to maintain the integrity of its organization, to ensure proper discipline therein and to remedy the injustice suffered by E[…]. In Khumalo and Another v Member of the Executive Council for Education: KwaZulu-Natal the Court described the duty as follows:

“Public functionaries, as the arms of the state, are further vested with the responsibility, in terms of section 7(2) of the Constitution, to “respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights in the Bill of Rights.” As bearers of this duty, and in performing their functions in the public interest, public functionaries must, where faced with an irregularity in the public administration, in the context of employment or otherwise, seek to redress it. This is the responsibility carried by those in the public sector as part of the privilege of serving the citizenry who invest their trust and taxes in the public administration.”

This duty is to be interpreted in the context of the special overarching obligation on Organs of State to uphold the rule of law. It was observed in Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality v Asla Construction (Pty) Ltd:

“This Court has repeatedly stated that the state or an organ of state is subject to a higher duty to respect the law. As Cameron J put it in Kirland:

“[T]here is a higher duty on the state to respect the law, to fulfil procedural requirements and to tread respectfully when dealing with rights. Government is not an indigent or bewildered litigant, adrift on a sea of litigious uncertainty, to whom the courts must extend a procedure-circumventing lifeline. It is the Constitution’s primary agent. It must do right, and it must do it properly. ”[1]

As pointed out in the first judgment, a review application could have been brought in terms of Section 158(1)(h) of the LRA, a municipality falling within the definition of “State” for the purposes of that Section. As the disciplinary code, which was contained in a collective agreement, proscribed any interference with the sanction, the holding of a second disciplinary hearing would not have been permissible. Any such challenge to the disciplinary sanction was required to have been brought in the form of a so-called rule of law review application and on the strength of the doctrine of legality given that it has authoritatively been held that it is not permissible, at least for the moment, in a State self-review to rely on the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act.

The Municipality did not however challenge the decision of the Presiding Officer. The explanation furnished for this failure by Mnyimba was that when he enquired from the legal advisor as to whether the sanction imposed by the Presiding Officer was susceptible to challenge:

“… he was advised that it could not and that once the two-week suspension had been served second defendant would in effect resume his employment with a clean slate.” (own underlining)

The understanding of Mnyimba was summarised in the first judgment as follows:

[Mnyimba] stated that when second defendant had served his suspension, he told plaintiff that with the best will in the world there was nothing that he could do to prevent second defendant returning to work or to prevent second defendant from coming into contact with her in the course of his duties.”

Had the Municipality launched an application to challenge the decision of the Presiding Officer and had it placed Jack on suspension, it may well be that the sorry state of affairs which ensued may not have materialized. To the observations made in the first judgment about the correctness of the legal advice received by the Municipality, I would add that the advice was not only wrong insofar as it was that the Municipality could not challenge the decision of the Presiding Officer, but it was also wrong in that it was to the effect that there was nothing further the Municipality could do to protect E[…] after the incident and Jack was at liberty to resume his duties with “… a clean slate”. The author of the legal advice was seriously mistaken on this count. The assault committed by Jack was not the type of conduct which could have been extinguished or wished away. As Sachs J observed in a matter concerning an application to stay a criminal prosecution:

“As the popular saying goes “Molato ga o bole” (Setswana) or “ical’aliboli” (isiZulu) – there are some crimes that do not go away.”[2]

The Municipality had a duty not only to show courtesy and respect to E[…]but further to provide her with a safe working environment. It was obliged to have taken steps to protect E[…] from the person who had assaulted her and who remained in the workplace. In a recent decision handed down by the Labour Appeal Court it was held that employers:

“… have a duty to provide a safe and healthy work environment for their employees and students, including protection from senior employees of predatory disposition.”

It would have been different if the Presiding Officer had found that the version of E[…] was untrue. But that is not what happened here. The Presiding Officer found that a male superior had committed a sexual assault on one of his female subordinates and that he had falsely denied committing that assault. The stance adopted by the Municipality that, in those circumstances, there were no measures which it could implement to protect E[…] was most unfortunate and regrettable. The Municipality stated that it had empathized with E[…] and that it could not understand the ruling of the Presiding Officer but that its hands were tied. Whilst I accept that the Municipality acted on the strength of legal advice (I note that this advice appears to have been informally given and no second opinion was sought), this does not change the circumstance that its approach of washing its hands of the matter, á la Pontius Pilate, fell woefully short of what was required of an employer in the circumstances. The Municipality abdicated its responsibilities to protect Erasmus and adopted a supine approach of bovine resignation.

How the plaintiff was dealt with:

After the decision was handed down, although there was no provision for it in the disciplinary code, E[…] nonetheless, out of desperation, lodged an appeal against the decision because she was of the view that the sanction was shockingly lenient. The Municipality did not revert to her regarding her appeal and it also did not discuss the disciplinary finding with her.

E[…] was thereafter left to fend for herself. The Municipality took no steps to support or empower her. She was offered no counselling or any other assistance. There was no communication to E[…]’s co-employees affirming support for her and condemning the conduct of Jack and no communication recording that conduct of the nature was unacceptable and in future would attract the sanction of dismissal. Rather, if anything, the message was that victims of sexual assault who were brave enough to come forward would not receive redress. The unrepentant perpetrator, Jack, was allowed to roam free in the workplace with unfettered access to E[…]. Although she no longer reported to Jack, he still exercised a degree of control over her. E[…] stated that on one occasion when she applied for leave after the assault, the Municipality took the stance that it was Jack who had the authority to approve her leave. She also said that Jack requested a meeting with her but, she refused to accede to this request.

In the aftermath of the incident E[…] explained that she felt stigmatized and experienced what is commonly known as victim shaming. By way of an illustration she mentioned how, on one occasion, some of her colleagues informed her that they would not be attending the Christmas party because E[…]’s presence would create a “bad vibe”. She perceived her colleagues as viewing her, not Jack, as the wrongdoer. She transferred, either fully or partially, the responsibility and culpability for what had happened onto herself. She felt marginalized and humiliated by scrutiny and gossip.

It is not in dispute that E[…] thereafter endeavoured valiantly to grin and endure the situation in which she then found herself. She was however not able to cope. She was often off sick for substantial periods as she continued to suffer emotionally and mentally as a result of the assault. There was no evidence of any enquiries made or concerns expressed by the Municipality about her absences and as to her welfare. She experienced feelings of betrayal, isolation and powerlessness. Bereft of any support from her employer, like many sexual assault victims she developed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (“PTSD”).

Steps taken by the plaintiff:

On 16 March 2011, the Plaintiff issued summons against the Municipality and the Jack (her Manager).

E[…] claimed damages in the following amounts:

Past medical, psychiatric and related expenses: R31 005.02.

Future psychological, medical, hospital and related expenses: R338 770.06.

Past loss of income: R1 323 700.00.

Future loss of income: R5 236 100.00.

General damages: R600 000.00.

Contumelia (offensive act or deliberate disrespect): R600 000.00.

Accordingly E[…] claimed damages totaling an amount of R8 129 575.02.

The court, in dealing with his claim, stated that:

“the conduct of the Municipality was truly an illustration of how not to manage a sexual assault in the workplace. The failure by the Municipality to take steps to protect E[…] had catastrophic consequences for her emotional and psychological well-being and her employment became unendurable. The first judgment summarises the position as follows:

“Plaintiff stated that after the disciplinary enquiry and the criminal trial had been disposed of, second defendant remained in the service of first defendant and she would still meet him in the offices and corridors at first defendant’s premises. She reported these meetings to Mr. Bomvane who advised her that now that the disciplinary proceedings and criminal case had been finalised there was nothing that they could do to keep him away from her. He told they did not know what to do (sic). In the meantime, plaintiff, who was suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, had sought the assistance of a psychiatrist who prescribed certain medication for her. Plaintiff stated that the medication assisted to a degree but that every time she saw second defendant she began trembling and crying. She could not sleep and she suffered from nightmares. Eventually, during October 2010, plaintiff could no longer cope with her work situation and she tendered her resignation, her last week of work being the first week of November 2010.

As was poignantly observed in the first judgment:

“…The awful irony was that Jack continued in his employment as the Corporate Services Manager whilst E[…] was forced to resign.”

The court also at one stage stated that:

At the time that E[…] resigned in 2010 she was a vibrant 23 year old woman occupying the post of Registry and Archives Clerk within the Municipality to which she had been permanently appointed with effect from 1 January 2010. Much water has since flowed under the bridge and it became apparent that the course of the life of the deeply traumatised 34-year old woman who testified at the trial on quantum in late July 2020 had been much changed as a result of the assault.

The court went on to find that:

“the stance adopted by the Municipality at the trial demonstrated a disturbing lack of appreciation of its legal obligation to have provided E[….] with a safe working environment. The Municipality appears to have been under the erroneous impression that conducting a disciplinary hearing amounted to taking steps to eradicate sexual harassment and cheerfully assumed that because it had conducted a disciplinary hearing this was sufficient in the circumstances”.

On 31 March 2016 the Court first judgment was delivered, the executive part of which reads:

“[82] Accordingly the following order will issue:

1. It is declared that the first and second defendants are jointly and severally liable for such damages as the plaintiff may prove she has suffered in consequence of the sexual assault upon her on 16 November 2009 at the offices of first defendant in Jansenville.

2. Defendants are ordered jointly and severally to pay the costs of the action on the merits, the one paying the other to be absolved.”

Various applications, technical arguments and attempts to settle the matter were made and failed.

On 3 September 2018, E […] was informed that the trial on quantum would be proceeding on 28 February 2019. It caused the postponement of the quantum trial.

On 10 July 2020, the Municipality tendered employment to E […] on the following terms:

“The first defendant hereby makes an offer of the following position of employment with the first defendant, in lieu of an offer of damages in regard to future loss of income, and in order to assist the plaintiff in mitigating her damages:

The first defendant offers the plaintiff reinstatement to a position commensurate with the plaintiff’s position of employment when she left her employment with the first defendant in November 2010 (that being the position of Administrative Assistant, Finance and Archives Clerk), within the current organisational structure, at Jansenville, effective from date of acceptance of this offer, with full applicable benefits and remuneration, and subject to all relevant statutory deductions.

Should the plaintiff accept this offer of employment, the first defendant will immediately transfer/move Mr Xola Jack to one of the satellite offices of the Dr. Beyers Naude Municipality and instruct Mr Jack that he may not have any contact with the plaintiff (including telephonic, by way of email or otherwise) in carrying out his duties in the course and scope of his employment with the first defendant. Mr Jack will furthermore not be permitted to enter the Jansenville offices of the first defendant during the plaintiff’s period of employment. Any failure by Mr Jack to adhere to these conditions will be viewed by the first defendant as serious misconduct.

Should the plaintiff accept this offer of employment, the first defendant undertakes to reimburse the plaintiff (to the extent that the relevant medical aid scheme does not cover such costs) for any required psychological counselling and/or psychological/psychiatrically related medication/medical treatment, for a period of one year after acceptance of this offer of employment, and in order to assist the plaintiff in re-integrating into her employment position with the first defendant.”

The plaintiff declined the offer.

When the quantum trial proceeded, the Judge dealt with the various applications, the refusal of the leave to appeal, the refusal of the settlement offers and other technical issues.

The Court, at one stage remarked that it is not in dispute that the spectre of the trial brought with it a whirlwind of emotions and a degeneration of her mental and emotional condition. Four days after receiving notice of the trial and on 7 September 2018 she suffered an anxiety attack and was taken to hospital. On 20 September 2018 she took 24 Panado tablets and was again taken to hospital although no treatment was considered necessary. In December 2018 she took a small overdose of her psychiatric medication (Ritrovil) but again no treatment was required. The trial was thereafter postponed.

On an undisclosed date in 2019, and on hearing about the Offer, E […] ingested poison but immediately spat it out causing her not to be able to eat for a week. On 21 January 2020 she cut her wrists with a broken bottle. The injuries suffered as a result thereof were not however serious and she did not require medical attention.

Conclusion:

After much deliberation and having dealt with the various issues surrounding the calculation of damages, the court ordered the payment of the following:

Uninjured

Injured

Loss

Past Loss of Earnings

Gross

R1,231,600

R 338,200

Contingency

5%

R 61,580

0%

R ---

Total Loss of Past Earnings

R1,170,020

R 338,200

R831,820.00

Future Loss of Earnings

Gross

R4,134,200

R1,573,200

Contingency

15%

R 620,130

55%

R 865,260

Total loss of Future Earnings

R3,514,070

R 707,940

R2,806,130.00

TOTAL

R3,637,950.00

Past psychiatric, medical and associated expenses R31,005.02

Future psychological, medical, hospital and related

expenses R30,000.00

General damages taking into account the R100,000.00

paid in terms of the order of 2 June 2020 R300,000.00

TOTAL R361,005.02

TOTAL DAMAGES AWARDED R3,998,955.02

0 notes

Text

Article by SALLR

Under which circumstances will insubordination justify dismissal?

The labour appeal court recently, in Maripane v Glencore Operations SA (Pty) Ltd (Lion Ferrochrome) (2019) 30 SALLR 163 (LAC), adopted the following approach:

There was an onus on the respondent to show that the dismissal, which was common cause, had been fair. This would have included showing, on a balance of probabilities, that the appellant had been guilty of the misconduct with which he had been charged and for which he had been dismissed. To justify dismissal, the insubordination had to be gross, meaning that the insubordination ‘must be serious, persistent and deliberate’.

In addition, whether the refusal to obey an instruction amounts to insubordination also depends on various factors, including:

- the employee’s conduct before the alleged insubordination,

- the wilfulness of the employee’s refusal to obey, and

- the reasonableness of the instruction (Workplace Law (above) at 175 and the cases cited therein fn. 125).

The reasonableness of any instruction also depends on its lawfulness and enforceability (see Mlaba v Masonite (Africa) Ltd and Others [1998] 3 BLLR 291 (LC) at 296I-297G and SACCAWU and Others v Mahawane Country Club [2002] 1 BLLR 20 (LAC) at paragraph [7]).

It seems axiomatic, that any instruction to do what is unlawful, or in breach of a contractual term is not reasonable.

0 notes

Text

NOT REPORTING AND NON-COMPLIANCE WITH COVID RULES CAN GET YOU FIRED – A WARNING TO BOTH EMPLOYERS AND EMPLOYEES BY THE LABOUR COURT

In a very recent (28 March 2021) and one of the first Labour Court cases dealing with issues relating to Covid, in the matter of Eskort Limited and Stuurman Mogotsi, Commissioner SS Ngada NO & the CCMA, the Labour Court reviewed a decision by a CCMA Commissioner and found that:

The dismissal of an employee for failing to disclose his covid status, was substantively fair.

The facts of the matter as summarized by the court:

The Applicant in the review matter conducts a butchery business on a national scale. They sell meat and cooked food to the public.

The first Respondent in the matter (Mr. Mogotsi), was employed as its Assistant Butchery Manager.

Mogotsi used to travel to and from work daily with a colleague, Mr Philani Mchunu (Mchunu) in a private vehicle. On 1 July 2020, Mchunu did not feel well and had consulted with a medical practitioner on the same date. Mchunu was then booked off sick from 1 to 3 July 2020, and had his sick leave extended on 4 July 2020. He was subsequently admitted to a hospital on 6 July 2020 and was informed on 20 July 2020 that he had tested positive for COVID-19.

At about the time that Mchunu initially fell ill, Mogotsi also started experiencing chest pains, headaches and coughs. He had consulted a traditional healer, who had booked him off on 6 and 7 July 2020 and also from 9 to 10 July 2020. The traditional healer happened to be his wife.

Upon being booked off by the traditional healer, Mogotsi was informed by management to stay at home. He nonetheless reported for duty after 10 July 2020. This was even after he became aware from 20 July 2020 of Mchunu’s positive results.

Mogotsi took a COVID-19 test on 5 August 2020 and was informed on 9 August 2020 via ‘SMS’ that he had tested positive. The concern however raised by the applicant is that despite having taken a COVID test on 5 August 2020 and being informed of his positive results on 9 August 2020, Mogotsi had reported for duty on 7, 9, and 10 August 2020, and personally came to the premises to hand in a copy of his results.

The applicant had COVID-19 policies, procedures, rules and protocols in place, and all employees had been constantly reminded of these through memorandum and other various means of communications posted at points of entry and also through emails.

Of further significance, however, is that Mogotsi was also a member of the in-house ‘Coronavirus Site Committee’, and was responsible for inter alia, putting up posters throughout the workplace, informing all employees what and what not to do in the event of exposure or even if they suspected that they may have been exposed to CoVID-19, and the symptoms they must look out for.

Other than the above, and upon the applicant having conducted its own investigations after Mogotsi’ test results were made known, it was discovered that on 10 August 2020, a day after he had received his results, he was observed on a video footage at the workplace, hugging a fellow employee (Ms Milly Kwaieng), who happened to have had a heart operation some five years earlier and had recently experienced post-surgery complications.

Again, from the video footage on 10 August 2020, Mogotsi was observed walking on the workshop without a mask. Upon Mogotsi’s test results being known, and after further investigations and contact tracing, a number of employees who had contact with him had to be sent home to self-isolate, amongst whom were Kwaieng and others who had other comorbidities.

Mogotsi had nonetheless conceded under cross-examination that he received the test results on 9 August 2020 but, alleged that he did not know that he needed to self-isolate. He further conceded having hugged Kwaieng on 10 August 2020, and further having walked on the shop floor without a mask. His excuse was that he was on a phone call at the time and that he needed to remove his mask to have a clearer conversation with his caller. His main contention was that despite asking for a direction after he had reported ill and informed management that he had been in contact with Mchunu, nothing was done, as business had continued as usual when he reported for duty.

Mogotsi was charged with:

(a)gross misconduct related to his alleged failure to disclose to the employer that he took a COVID-19 test on 5 August 2020 and was waiting for his results;

b) gross negligence in that after receiving his COVID-19 test results which were positive, he had failed to self-isolate, continued working on 7, 9 and 10 August 2020, and thus put the lives of his colleagues at risk. It was further alleged that during the period he had reported for duty, he failed to follow the health and safety protocols at the workplace, including failing to adhere to social distancing.

He was found guilty and dismissed by the employer. The employee referred the matter to the CCMA.

The CCMA’s findings:

Given the above evidence, which was mainly common cause, the Commissioner had in the award, stated that he had regard to ‘the provisions of the LRA, CCMA Guidelines, the Code of Good Practice, and relevant case law’, and came to the following conclusions:

Mogotsi’s allegations that he was dismissed on account of being victimised ought to be rejected.

The employer did not have any instructions or rule that expressly compelled its employees to inform it when they had undertaken COVID-19 tests. However, there was a rule in place that required employees to inform the employer when they suspected that they had been infected. Implied in that rule was the need for employees to inform the employer of their COVID-19 tests. To that end, Mogotsi was therefore required to inform the employer of the test he took, and he was therefore guilty of failing to report his test to the employer.

The conduct of Mogotsi of having reported for duty in circumstances where he knew of his positive test results on 9 and 10 August 2020 and did not inform the employer of the test; of hugging fellow employees, and walking around the butchery without a mask, was ‘extremely irresponsible’ in the context of the pandemic, and he was therefore grossly negligent.

In determining the appropriateness of the sanction and having had regard to the provisions of paragraph 96 of the CCMA Guidelines, the employer in the light of its own disciplinary code and procedure which called for a final written warning in such cases, failed to justify the sanction of dismissal, and had thus deviated from its own disciplinary code and procedure.

The sanction of dismissal was therefore not appropriate on account of that deviation, making the dismissal substantively unfair. To this end, Mogotsi was to be reinstated retrospectively, without back-pay, and a final written warning placed on his record.

The employer took this decision on review to the Labour Court.

The Labour Court’s evaluation of the evidence:

The court found that the sanction of dismissal was indeed appropriate in this case given the considerations below:

Mogotsi had at the very least, from 20 July 2020, been aware that he had been in contact with Mchunu, who had tested positive for COVID-19. On his own version, he had experienced known symptoms associated with COVID-19 as early as 6 July 2020. It cannot therefore be probable for him to allege that he was not aware of the known symptoms, nor did he not know he had those symptoms. Be that as it may, he had over that period until 11 August 2020, recklessly endangered not only the lives of his colleagues, and customers at the workplace, but also those of his close family members and other people he may have been in contact with.

Mogotsi’s conduct came about in circumstances where on the objective facts, and by virtue of being a member of the ‘Coronavirus Site Committee’, he knew what he ought to have done in an instance where he had been in contact with Mchunu and where on his own version, he had experienced symptoms he ought to have recognised. He nonetheless had continued to report for duty as if everything was normal, despite being told on no less than two occasions to stay at home during July 2020.

Mogotsi’s conduct was not only irresponsible and reckless but, was also inconsiderate and nonchalant in the extreme. He had ignored all health and safety warnings, advice, protocols, policies and procedures put in place at the workplace related to COVID-19, of which he was fairly aware of given his status not only as a manager but also part of the ‘Coronavirus Site Committee’.

For reasons which are clearly incomprehensible, Mogotsi had through his care-free conduct, placed everyone he had been in contact with whether at the workplace or at his residence at great risks. Even more perplexing is the reason he would go about the workplace mask-less and hugging fellow employees, in circumstances where he knew or ought to have known the consequences of his actions, especially after having become aware of Mchunu’s results. There is a COVID-19 term which has been coined for this type of behaviour, which out of respect for Mogotsi’s dignity, I will refrain from repeating in this judgment due to its derogatory nature.

However, the consequences of Mogotsi’s conduct were not only dire for the applicant but equally so for all of those employees with whom he had contact with, their own families and communities. In this regard, the applicant’s operations were affected in that a number of those employees had to be given time off to quarantine, and whilst in self-isolation, this had obviously impacted on their immediate family members.

In the midst of all the monumental harm he had caused, and which was clearly foreseen, Mogotsi could only come up with the now often used defence that he was victimised. At no point did he show any form of contrition for his conduct. At most, the evidence presented before the Commissioner pointed out to Mogotsi as an employee who was not only grossly negligent and reckless, but also dishonest. He had failed to disclose his health condition over a period of time, sought to conceal the date upon which he had received his COVID-19 test results, and completely disregarded all existing health and safety protocols put in place not only for his own safety but also the safety of his co-employees, and the applicant’s customers.

The gross nature of Mogotsi’s conduct is such that a trust and working relationship between him, the applicant, and his fellow employees, cannot by all accounts be sustainable. This is especially so in circumstances where on the applicant’s version, other employees had been dismissed for similar acts of misconduct, and where Mogotsi had failed to appreciate, let alone acknowledge the monumental harm, anxiety and strain he had caused on his co-employees and their

immediate families, but also on the operations of the applicant.

It follows that a dismissal was indeed an appropriate sanction.

Mogotsi’s care-free conduct however also brings into question the seriousness with which the applicant and its own employees also attaches to the dangers posed by this pandemic at the workplace, and whether the measures it has in place are adhered to, and effective in mitigating the effects of this pandemic. This is particularly so in circumstances where Mchunu had reported ill since 1 July 2020, and particularly after 20 July 2020, when his positive COVID-19 test was made known.

Upon investigating the matter after Mogotsi had tested positive, it was discovered that not only had he hugged Kwaieng who had comorbidities, but that he had also walked around the workplace without a mask. The questions that need to be posed despite the applicant having all of these fancy COVID-19 policies, procedures and protocols in place, is whether more than merely dismissing employees for failing to adhere to the basic health and safety protocols is sufficient in curbing the spread of the pandemic? How can it be, that in the midst of the deadly pandemic, the applicant still allows mask-less ‘huggers’ walking around on the shop floor? Of further importance is notwithstanding all of these protocols and awareness campaigns about this pandemic, why would any employee in the workplace, especially one with comorbidities, hug or reciprocate hugging in the middle of a pandemic? Does a basic principle such as social distancing mean anything to anyone at the workplace? Furthermore, what is the responsibility of the applicant and its employees when other employees or even customers, are seen roaming the workplace or shopfloor mask-less? Of even critical importance is what steps were taken in ensuring the health and safety of all the employees and customers, where at least from 20 July 2020, Mchunu’s test results were known? All of these questions need to be addressed in the light of Mogotsi’s version that after Mchunu’s test results were made known, business at the store had continued as usual, hence he had continued reporting for duty.

It is appreciated that the applicant had as per its evidence, taken disciplinary measures against other employees for violating the health and safety protocols put in place, including dismissals. However, the facts of this case in my view clearly compels the need for serious introspection by the applicant and all other employers in the light of the above questions posed, in regard to whether existing health and safety measures and protocols in place are being taken seriously by everyone affected. It is one thing to have all the health and safety protocols in place and on paper. These are however meaningless if no one, including employers, takes them seriously.

In the end however, in the light of the evidence led at the arbitration proceedings, the egregious nature of Mogotsi’s conduct, and its impact on both the applicant and its employees, the arbitration award of the Commissioner completely fell outside the bounds of reasonableness. It was in the light of all of these considerations that an order was made on the hearing date, setting aside that award, and substituting it with an order that the dismissal of Mogotsi was substantively fair.

0 notes

Text

Being high at work - not in a good way.

Some confusion may exist with employers about the use of cannabis at work after the decriminalization of the private use thereof by the Constitutional Court, during 2019.

The CCMA had to deal with such matter recently in the case of Mthembu and others v NCT Durban Wood Chips [2019] 4 BALR 369 (CCMA).

The three applicants were among several employees who were dismissed after testing positive for cannabis during a test conducted during working hours

The environment in which they worked was highly dangerous involving dangerous machinery and vehicles, as well as the conveying of large logs weighing between 30 and a 100 kgs which can cause fatalities. The company therefore claimed that it had a zero-tolerance policy to working under the influence of alcohol and drugs.

The company had a substance abuse policy and held regular “toolbox” safety talks with its employees in order to protect the employees. They were aware of the policy and the company proved thus. The policy stated that the possession, sale or use of illegal drugs is not consistent with the company needs to operate in a safe and efficient fashion. No employee of the company may therefore use or possess unlawful drugs at any time.

The applicants were charged with being under the influence of intoxicating substances whilst on duty and dismissed. The three admitted that they were under the influence but challenged their dismissal on the basis that they did not use the drug during working hours.

The initial urine tests were backed up by subsequent laboratory testing.

The Commissioner took cognizance of the decision by the Constitutional Court in the matter reported as Prince v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and others and related matters wherein it was pronounced that the legislation criminalizing the private use of cannabis is inconsistent with the Constitution. The Court emphasized the unconstitutionality with the context of private use and consumption, which the legislator considered not to cause undue harm.

It furthermore considered the dangers around intoxication which became the element for consideration and found that, like alcohol, such intoxication could impair one’s ability to work to the standard, care and skill required by the employer. The employer could therefore take disciplinary action against the employees where the intoxication translates into an offence.

The Commissioner then considered the high degree of safety required of companies working with heavy machinery and other generally dangerous equipment and found that it is reasonable for such employer to have rules regulating the consumption of such substances at the workplace or reporting o work under the influence thereof.

The employees were found to have willfully disregarded the workplace rules. It was noted that it was incumbent upon the employees to inform the employer of any dependency issues they may have had and that they had sufficient time to adjust their private use to ensure that when the smoked cannabis for private use, they should not report for work under the influence.

The Commissioner found that the employees did not show any real remorse, not did they give any undertaking that it would not happen again (them reporting to work under the influence). It was made clear that whilst what they did in private cannot be limited by the employer, they are nevertheless expected to comply with the safety standards of the respondent which are designed to protect life and limb of not only the employees involved, but also that of other employees.

Their dismissal was found to be fair.

As is the case with the consumption of alcohol, employers are advised to rely on more than just a drug test to show that an employee was under the influence of cannabis – circumstantial evidence supporting the drug test such as - impaired speech, difficulty walking in a straight line, other physical signs, etc.

0 notes

Text

IS IT NECESSARY TO GIVE AN EMPLOYEE AN OPPORTUNITY TO MAKE REPRESENTATIONS PRIOR TO HIS SUSPENSION, PENDING A DISCIPLINARY HEARING – OR NOT?

Until recently, it was necessary for employers in the private sector to conduct a so-called pre-cautionary suspension hearing before suspending an employee. This implied that the employer had to give an employee an opportunity to make representations as to why he/she should not be suspended.

It is known that when an employer suspects an employee of committing an act of misconduct, the employer may want to place that employee on what is usually referred to as a "precautionary suspension", pending a disciplinary hearing.

Up to and until a recent decision (in February 2019), by the Constitutional Court in the matter of Allan Long v South African Breweries (Pty) Ltd & Others [2018] ZACC7, it was expected of an employer to give the employee a chance to make representations on why he or she should not to be suspended, prior to a decision being taken in this regard.

Background

Herewith a summary of the facts of the matter from an article by Jayson Kent & Sade Maitland from ENSafrica (South Africa: Precautionary Suspension: Do Employees Have the Right to Make Representations:

“The employee was responsible for ensuring that SAB complied with all legal requirements in his district, which included ensuring that SAB's fleet of delivery trucks was properly licensed and that all of the vehicles were roadworthy. During late 2012, it was discovered that several the vehicles and trailers were unlicensed and/or not roadworthy. The employee issued instructions to certain subordinates to remedy the situation but, did not proactively involve himself in ensuring that this was done.

In May 2013, a fatal accident involving one of the unroadworthy vehicles occurred. The employee was placed on suspension pending an investigation into the issues relating to the fleet. Approximately three months later, the employee was subjected to a disciplinary hearing and dismissed. He referred disputes relating to his suspension and his dismissal to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (the "CCMA")

The CCMA decision:

At the CCMA the Commissioner made a finding that the employee had been unfairly suspended – an unfair labour practice. The grounds stated by him were that:

the suspension was "unduly long", and;

that the employee was not provided with an opportunity to make representations before he was suspended.

The Labour Court decision:

The employer took the decision of the CCMA on review to the Labour Court who overturned the award by the Commissioner.

It held that:

the employee’s suspension was not an unfair labour practice;

the employee was in fact guilty of one of the charges (dereliction of duties) and that the award made by the Commissioner was unreasonable;

where a suspension is pre-cautionary, and with full salary, there is no requirement for an employee to be given an opportunity to make representations before being placed on precautionary suspension.

The court added that as was stated in the matter of Mashego v Mpumalanga Provincial Legislature and other:

“It is generally accepted than an employer has discretionary power to suspend an employee if the presence of such an employee at work is likely to undermine an investigation”

The Labour Court set aside the decision of the CCMA and declared the dismissal to have been fair. Mr. Long was ordered to pay SAB’s costs.

The Labour Appeal Court decision:

The employee first sought relief from the Labour Appeal Court, who refused to grant leave to Appeal. The employee then applied for leave to appeal against the Labour Court’s judgement in the Constitutional Court.

The Constitutional Court decision

The Constitutional Court held that the finding of the Labour Court regarding the issue of an opportunity to make representations could not be faulted.

Because the Constitutional Court simply aligned itself with the Labour Court's findings, it is necessary to consider the findings of the Labour Court.

The Labour Court set out the important differences between the two possible species of suspension – the first being a suspension as a disciplinary sanction, and the second being a suspension as a "holding operation" or a precautionary suspension. A suspension as a disciplinary sanction can only follow a fairly conducted disciplinary proceeding and is usually as an alternative to dismissal. It is important to distinguish this from a precautionary suspension, the species of suspension dealt with in this matter. This distinction is consistent with the case law on the subject. The Labour Court quoted Mashego v Mpumalanga Provincial Legislature and Other, wherein the Labour Court confirmed that:

"It is generally accepted than an employer has discretionary power to suspend an employee if the presence of such an employee at work is likely to undermine an investigation."

According to the article from ENSafrica (as stated above) the Labour Court held that the fairness or otherwise of a precautionary suspension is determined by three considerations:

the suspension must be directly linked to a pending investigation or process. The suspension must serve to protect the integrity of that investigation or process, or to mitigate the risks that the presence of that employee in the workplace may pose to the investigation or process. It is important that the suspension must not be for the purposes of punishing the employee;

the second consideration relates to prejudice to the employee. Where a suspension is on full pay (which it ought to be in the case of a precautionary suspension), the Labour Court stated that prejudice to the employee is "curtailed and will not readily be seen to be unfair." The Labour Court also stated that damage to the employee's reputation would not be a consideration, as this would render almost every precautionary suspension unfair; and

the precautionary suspension should not be "unduly long." What will be unduly long will depend on the facts present in a particular set of circumstances.

The Labour Court also held that it is not necessary for the employer, at the stage of implementing a precautionary suspension, to substantiate the allegations of misconduct – it is enough for the employer to hold a reasonable belief that the misconduct took place.

The Constitutional Court decision:

The Constitutional Court partly upheld the appeal by the employee only in respect of the cost order.

It however upheld the decision by the Labour Court on the merits of the matter namely that the Labour Court correctly held that:

an employer is not required to give an employee an opportunity to make representations before a pre-cautionary suspension;

the dismissal was fair.

Other Implications of the decision:

Very interestingly, the court also found that a suspension pending an investigation is a precautionary measure and does not constitute disciplinary action and that the requirements in terms of the Labour Relations Act, 1995 relating to fair disciplinary action do not apply.

The above ruling, in my view has at least one very important consequence. Surely it must then mean that the requirement to consult with a union before disciplining a shop steward (Section 4 (2) of The Code of Good Practice: Dismissal) published in terms of the Labour Relations Act), does not include the need to consult, prior to the shop steward’s suspension, since suspension is not considered to be disciplinary action!

As warned by the authors in the ENSafrica article mentioned earlier herein, the following should also be noted:

the right to be provided with an opportunity to make representations may arise from other sources, such as a contract of employment, a collective agreement, a disciplinary code and procedure, and/or an established workplace practice. If the right to be given such opportunity does exist in some other source, it must be complied with;

A failure to provide a hearing in breach of a right derived from these sources could also give rise to an employer liability. If such a possible liability exists, employers would do well to seek legal advice prior to deciding whether to suspend an employee.

Employers should look at their policies, Disciplinary Codes or other relevant documentation and ensure that it complies with this decision.

DJJ Lemmer

0 notes

Text

THE NATIONAL MINIMUM WAGE ACT AND PARENTAL LEAVE IN SOUTH AFRICA

National Minimum Wage Act:

The President, on 23 November 2018, signed the National Minimum Wage Act (NMWA) into law. It has subsequently been announced that the National Minimum Wage Act would come into effect on 1 January 2019.

The ideal of a minimum wage for all workers started a long time ago and its promulgation was the eventual fulfillment of the 1955 Congress of the People declaration that there would be would be a minimum wage for all workers.

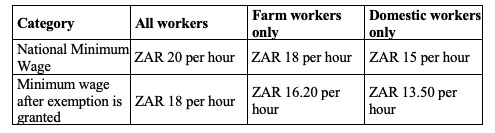

In terms of this Act, all employers, irrespective of which industry they are operating in, must pay at least the minimum wages as set out below:

R 15.00 per hour for domestic workers;

R 18.00 per hour for farm workers; and

R 20.00 per hour in respect all other employees.

It is possible for employers to apply for limited exemption.

The minimum wage figures set out above, will remain in force for the next two years (ie until December 2020). In January 2021, the Minister of Labour will announce whether the national minimum wage will be adjusted in any way.

Exemption process:

In an article by Webber Wentzel, (Understanding the exemption to the new national minimum wage) the exemption process is explained.

Section 15 of the NMWA, read together with the Regulations, provides an exemption process for employers. The exemption process is specifically created for employers who can show that they cannot afford to pay the national minimum wage to workers. An exemption will only be granted if the following criteria are satisfied by the applicant employer:

the employer cannot afford to pay the national minimum wage; and

representative trade union(s) of the workers have been meaningfully consulted or, if there are no trade union(s), the affected workers have been meaningfully consulted.

To assess affordability, elements of profitability, liquidity and solvency are taken into account. The decision-making process is rigorous and employers will need to ensure that they submit comprehensive financial and organisational information when applying for exemptions.

No exemption may be granted where the wage is below the following wage thresholds:

90% of the national minimum wage in respect of workers other than farm workers and domestic workers;

90% of the national minimum wage in respect of farm workers; or

90% of the national minimum wage of domestic workers.

The nature of exemptions will therefore be limited as follows -

The table above illustrates that it is not possible for an employer to be exempt from the national minimum wage by a large amount. It is essentially only possible for an employer to obtain a 10% decrease (as a maximum) in the national minimum wage through the exemption process.

If successful, the employer will be provided with an exemption notice which will contain the following information:

the period of exemption;

the wage(s) that the employer is required to pay workers; and

any other relevant condition.

If unsuccessful, the employer will also be provided an exemption notice which will contain reasons for the refusal.

The exemption process is managed by the Department of Labour through an online system called the National Minimum Wage Exemption System. In order to apply for an exemption, the table below provides important information.

Parental leave provisions:

Prior to 23 November 2018, South African labour laws provided for specified types of leave for employees such as annual leave, sick leave, family responsibility - leave and unpaid maternity leave.

In terms of the latest amendments to the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, 75 of 1997 (“BCEA”), a new category of leave, known as “Parental Leave” has been introduced in South Africa as from 1 January 2019:

- The Amendment Act specifies that an employee who is a parent of a child will be entitled to 10 days parental leave, which may be granted from the day of the child’s birth;

- In addition, the Amendment Act provides for 10 consecutive weeks of adoption or parental leave to parents of adopted children under the age of two years, starting on the day of the granting of a child’s adoption order;

- Lastly, the amendment provides for “Commissioning parent leave” of 10 weeks where an employee is a commissioning parent (“opdraggewende ouer”) in a surrogate motherhood agreement. It can be taken from the date on which the child is born. Where there are 2 commissioning parents- only one can take commissioning parental leave and the other may apply for parental leave.

The purpose of the amendments is to ensure benefits and equal treatment for families in the LGBTQI community. Previously, same sex partners were not able to take leave upon the adoption of a child/birth of a child, or where a birth took place after being carried by a surrogate.

Female employees already benefitting from maternity leave (which remain unpaid), are excluded from these new benefits. The 3 days family responsibility leave previously given to fathers when a child was born, has been scrapped.

Contrary to what has been published by the media, this leave is indeed unpaid leave. An employee may however claim from the South African Unemployment Insurance Fund, subject to certain requirements in respect of prior employment.

Employers will have to revise their policies and procedures to provide for the changes to the Basic Conditions of Employment Act.

0 notes

Text

LABOUR BROKER OR THE CLIENT: WHO IS THE REAL EMPLOYER?

Background:

In a recent decision by the Labour Appeal Court, the court supported the “single employer” interpretation providing clarity regarding an issue which caused so much uncertainty in respect of the position of employees in Temporary Employment Services (TES).

The uncertainty resulted from diverging interpretations of section 198A of the Labour Relations Act. Recent amendments attempted to codify the rights of workers employed in non-standard (temporary) forms of work.

In short, as stated in a different article on this issue (bbrief, Labour Brokers: Labour Appeal Court Supports Single Employer Interpretation, by James, 21 July 2017), the uncertainty resulted from two diverging schools of thought.

The one group suggested that the client of a labour broker “automatically” becomes the employer after three months. The other school argued that the employees now employed by the client of the labour broker, remain employees of the labour broker - resulting in the employees having two employers.

The decision of the Johannesburg Labour Appeal court in the matter of NUMSA V Assign Services/Kristi Shelving & Racking (Pty) Ltd (case no: JA 96/15) went some way towards clarifying the rights and duties arising from the use of a labour broker to provide employees.

The facts of the case: (as verbatim summarised in the judgement)

Krost offers storage solutions. This entails manufacturing steel racking, shelving, mezzanine floors and lockers. While Krost does carry some stock, it generally quotes and works on projects. Accordingly, the product manufactured by it is generally customised.

Krost employs 40 salaried employees and approximately 90 wage staff who work in the factory. Krost manages and pays its own employees.

Assign supplies labour to Krost. The number of placed workers fluctuated from between 22 and 40 at any given time, with fluctuation being dependent on the nature of the projects awarded to Krost.

As at 01 April 2015, 22 placed workers (“the placed workers”) had been supplied by Assign to Krost for a period in excess of three months on a full-time basis, and their placement predated 01 January 2015.

The placed workers fall within the scope of application of section 198A(3)(b), and are not affected by any of the exclusions listed in section 198A(1) or (2).

As at present, the placed workers continue to be assigned by Assign to Krost, and, subject to the outcome of this matter, the TES arrangement between Assign and Krost is likely to continue in the foreseeable future.

The placed workers work shoulder to shoulder with Krost’s workforce. Krost manages the placed workers on a day-to-day basis. Assign is responsible for disciplining them.

Of Krost’s 90 wage staff in the factory, about 80% are NUMSA’s members. Several of the placed workers are also members of NUMSA.

Often Krost’s management will meet with NUMSA’s representatives together with workers placed by Assign who are NUMSA’s members. Occasionally, representatives from Assign’s management will be called to attend meetings together with NUMSA. This is normally when collective issues such as wages are discussed.

There is pay parity between Krost’s wage staff and the placed workers.

Krost has, however, received feedback that the placed workers are inclined towards asserting a right to being employed exclusively by Krost, which obviously has the potential for labour unrest (in the absence of the issue being determined by the CCMA).

The controversial question is who becomes the employer of the placed workers when a period of three months referred to s198A(3)(b) of the LRA kicks in.

Assign’s contention has been that the correct interpretation of s198A(3)(b), which is also referred to as the deeming provision, should be that workers placed by it at Krost remain employees of Assign for all purposes, and are deemed to also be employees of Krost for the purposes of the LRA. This situation is referred to as the “dual employment” position.

NUMSA, on the other hand, contended that in terms of the deeming provision, the placed workers are with effect from 01 April 2015, deemed to be employees of Krost only for purposes of the LRA. This position is referred to as the “sole employment” position.

The applicable legislation:

Section 198A of the Labour Relations Act (“LRA”) reads:

‘Application of section 198 to employees earning below earnings threshold

(1) In this section, a ‘temporary service’ means work for a client by an employee—

(a) for a period not exceeding three months;

(b) as a substitute for an employee of the client who is temporarily absent; or

(c) in a category of work and for any period of time which is determined to be a temporary service by a collective agreement concluded in a bargaining council, a sectoral determination or a notice published by the Minister, in accordance with the provisions of subsections (6) to (8).

(2) This section does not apply to employees earning in excess of the threshold prescribed by the Minister in terms of section 6(3) of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act.

(3) For the purposes of this Act, an employee—

(a) performing a temporary service as contemplated in subsection (1) for the client is the employee of the temporary employment services in terms of section 198(2); or

(b) not performing such temporary service for the client is—

(i) deemed to be the employee of that client and the client is deemed to be the employer; and

(ii) subject to the provisions of section 198B, employed on an indefinite basis by the client.

(4) The termination by the temporary employment services of an employee‘s service with a client, whether at the instance of the temporary employment service or the client, for the purpose of avoiding the operation of subsection (3)(b) or because the employee exercised a right in terms of this Act, is a dismissal.

(5) An employee deemed to be an employee of the client in terms of subsection (3)(b) must be treated on the whole not less favourably than an employee of the client performing the same or similar work, unless there is a justifiable reason for different treatment.

(6) The Minister must by notice in the Government Gazette invite representations from the public on which categories of work should be deemed to be temporary service by notice issued by the Minister in terms of subsection (1)(c).

(7) The Minister must consult with NEDLAC before publishing a notice or a provision in a sectoral determination contemplated in subsection (1)(c).

(8) If there is conflict between a collective agreement concluded in a bargaining council, a sectoral determination or a notice by the Minister contemplated in subsection (1)(c)—

(a) the collective agreement takes precedence over a sectoral determination or notice; and

(b) the notice takes precedence over the sectoral determination.

(9) Employees contemplated in this section, whose services were procured for or provided to a client by a temporary employment service in terms of section 198(1) before the commencement of the Labour Relations Amendment Act, 2014, acquire the rights contemplated in subsections (3), (4) and (5) with effect from three months after the commencement of the Labour Relations Amendment Act, 2014.’

What the court decided:

As stated by Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr )(”CDH”) (Employment Alert, NUMSA VS ASSIGN SERVICES: THE LAC WEIGHS IN ON THE DEEMING PROVISION, 11 July 2017), the unique triangular relationship created by a Temporary Employment Service (TES), an employee rendering services and the client of the TES, and deeming provision has seen intense scrutiny in the matter of NUMSA and Assign Services.

The Court first analysed the decisions of the various forums on the path of the matter to the Labour Appeal Court.

At the CCMA, it was decided that the client of the labour broker only becomes the employer after three months.

On review by the Labour court it was decided that the employment relationship between the broker and the employees continued to exist and that the broker thus also remained an employer.

The Labour Appeal Court disagreed and stated that there are not two employment contracts.

The Labour Appeal Court (LAC) found that, for the purposes of the Labour Relations Act, no 66 of 1995 (LRA), once the deeming provision kicks in, the TES falls out of the picture and the client is the sole employer.

“The purpose of the deeming provision is not to transfer the contract of employment between the TES and the placed worker to the client, but to create a statutory employment relationship between the client and the placed worker. Bearing in mind that the purpose of the amendment was to have the temporary employment service restricted to one of “true temporary service” as defined in s198A of the LRA, the intention must have been to upgrade the temporary service to the standard employment and free the vulnerable worker from atypical employment by the TES. It would make no sense to retain the TES in the employment equation for an indefinite period if the client has assumed all the responsibilities that the TES had before the expiration of the three-month period. The TES would be the employer only in theory and an unwarranted “middle-man” adding no value to the employment relationship”.

The LAC found that the sole employer interpretation was in keeping with the explanatory memorandum accompanying the LRA Amendment Bill, tabled in 2012. The memorandum records that:

‘’The amendments further regulate the employment of persons by a TES in a way that seeks to balance important Constitutional rights. The main thrust of the amendments is to restrict the employment of more vulnerable, lower-paid workers by a TES to situations of genuine and relevant ‘temporary work’, and to introduce various further measures to protect workers employed in this way.”

According to the CDH article (see above):

The LAC rejected the dual or parallel employer interpretation. It found that the protection against unfair dismissal and unfair discrimination in the context of s198A of the LRA did not support this interpretation but rather that this protection is a measure to ensure that the placed employees are not treated differently from the employees employed directly by the client. The purpose of these protections, the court found, is to ensure that the deemed employees are fully integrated into the enterprise as employees of the client. The employment relationship between a client and the placed employee is created by a statutory deeming clause. Hence, the court found, the placed workers become employed by the client for an indefinite period and on the same terms and conditions to the employees of the client performing the same or similar work.

The LAC found that the sole employer interpretation did not ban the operations of a TES. It, however, regulated the TES by restricting it to genuine temporary employment arrangements in line with the purpose of the amendments to the LRA. The TES remains the employer of the placed employee and is responsible for its statutory obligations only until the employee is deemed the employee of the client.

The court concluded that the intention of the amendment was to upgrade temporary service to standard employment and free vulnerable workers from atypical employment by the TES. It found that there was no sense in retaining the TES in the employment equation for an indefinite period if the client has assumed all the responsibilities that the TES had before the expiration of the three-month period. The TES was the employer only in theory and an unwarranted ‘’middle man’’ adding no value to the employment relationship.

In terms of this judgment, the employment relationship between the placed worker and the client arises by operation of law, independent of the terms of any contract between the placed worker and the TES.

Conclusion:

It is important to note that the decision discussed herein does not constitute a ban on labour brokers.

The correct use of fixed-term contracts, according to the prescripts of section 198B(3)&(4) of the LRA, may still continue. Should the conditions of section 198B however not be complied with and the justification of the initial temporary relationship becomes something other than “truly temporary”, the employment relationship also must change to a more permanent one.

The decision discussed herein will have serious consequences for labour brokers and may well be appealed to the highest court – the Constitutional Court.

DJJ Lemmer

0 notes

Text

Pitfalls when firing an employee

See link: 28 Experts Warn Against Pitfalls When Firing an Employee

0 notes

Text

Selling or buying a business - consequences for employees

When a business is sold what happens to the employees?

It is submitted that it is trite that under common law, the sale, closure, merger or takeover of a business results in the termination of the contracts of employment in existence between the business and its employees.

According to Grogan (Workplace Law, 11th edition. Reprinted 2016) on p. 346, the principle which is applied here is that an employer cannot “force” its employees to work for another.Therefore, under the old 1956 Labour Relations Act (“the LRA”), an employer who wanted to close or sell his business was deemed to have done so for operational requirements, and was thus obliged to pay severance pay to its employees (Grogan).

Under the new LRA, the position is different. Section 197 of the LRA, the contracts of employment of the existing employees, are automatically transferred to the new employer subject to the provisions of the section.

Section 197:

In terms of section 197 of the Labour Relations Act (”the LRA”), the sale of a business as a going concern takes place subject to the provisions of the LRA.The Act in section 197 thereof deals with the transfer of a contract of employment and defines:“Business” to include the whole or part of any business, trade, undertaking or service.

“Transfer” means the transfer of a business by one employer (the old employer) to another employer (the new employer) as a going concern.

In short, the relevant section contains provisions which protects the rights of the employees of the old employer when they are transferred to the new employer. The new employer is automatically substituted in the place of the old employer in respect of all contracts of employment (verbal or otherwise) in existence immediately before the transfer.

All rights and obligations between the old employer and an employee at the time of the transfer continue in force as if they had been rights and obligations between the new employer and the employee.Anything done before the transfer by or in relation to the old employer, including the dismissal of an employee or the commission of an unfair labour practice or act of unfair discrimination, is considered to have been done by or in relation to the new employer.

The transfer does not interrupt an employee’s continuity of employment, and an employee’s contract of employment continues with the new employer as if with the old employer.The new employer is not allowed to employ the employees on terms and conditions less favourable to the employees than those on which they were employed by the old employer.

The new employer is bound by any collective agreement (agreement with a union) concluded prior to the transfer.Section 197(7) lists a number of issues that need to be agreed upon by the old and new employer.

Some of these are:

Leave accrued to the employees;

Any severance pay due;

Any other payments due to the employees.