Text

A quick translation:

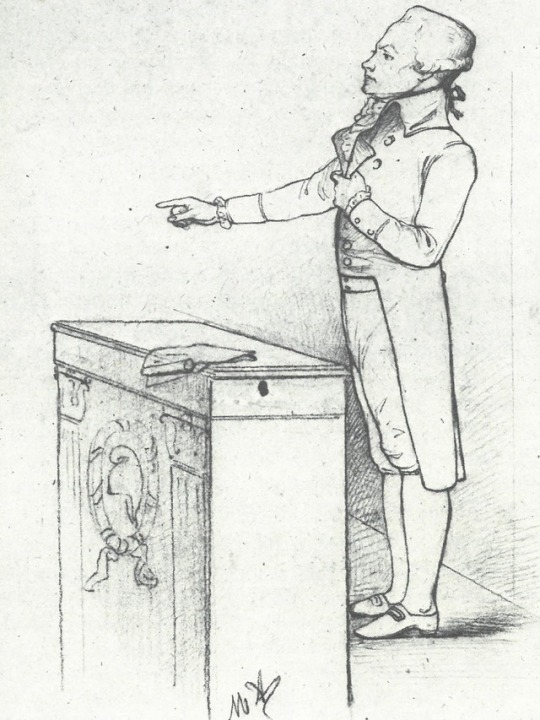

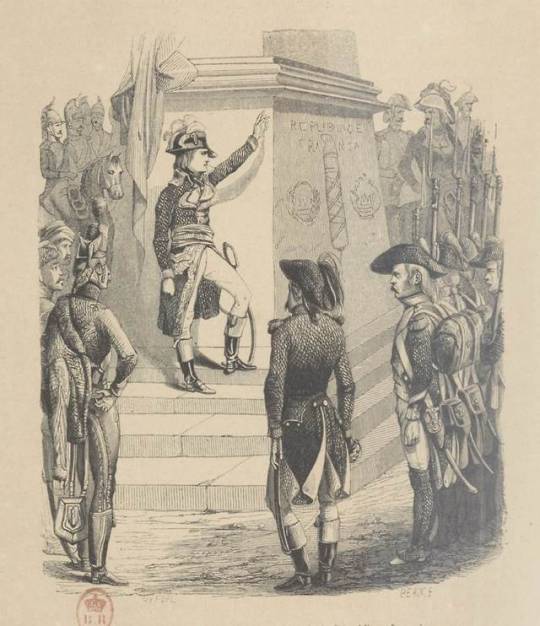

The armies of the Republic assumed formation in the face of the enemy, who was watching bewilderedly. Proclaiming the decree of the Convention and holding it in their hand, the Commissars of the Convention passed through the lines of soldiers; not a single sound of muttering was heard; the order appeared desirable to all of them and they waited for it. Prieur, supported by iron lungs [?], surrendered himself to his rapture, spoke [while] fighting against the echo and the tumultuous noise of delight, and closed [his speech] by exclaiming: "Behold, the army of the enemies; you are called either to annihilate it or to enlighten it. May no king sully the soil of our fatherland with his presence! Away with regality! – – – – – – – as far as the globe's frontiers reach! Long live the Republic! –– It shall be annihilated! Long live the Republic!", the unanimous mass of the army repeated under the clang of arms, waving their hats. – And the duke had to watch calmly, as regality was mocked right before his eyes. He, the avenger of dukes and duchesses, why didn't he let fly his fists? Rather, it seems that he benevolently came to the aid of the Revolution with a favourable crisis, to make it sweat out the last remains of feudality, otherwise he would have won victories, as Phyrrus, before he admiringly retreated before the Romans. The decree, which abolished regality in France forever in spite of the aristocrats' wrath, deserves respect in this regard, and it may appear audacious, if the despots' dignity had not fallen off by itself like a rotten fruit. Their overthrow is nothing but the harbinger of what, sooner or later, is also bound to happen in other realms. The dukes' pride falls with accelerated force, and at the end of the century we will see beggar kings, as there had been beggar kings in the beginning; as for myself, if, as I project now, the pickled cabbage [= Sauerkraut] factory does not fail, I hope [to be able] to give alms and something to eat [= Vesperbrot] to more than one of them.

(As the language is quite antiquated, it was not easy to find corresponding terms, so the translation is rather loose at times. Still, I hope this helps!)

Y aurait-il parmi mes abonnés un-e germanophone qui voudrait bien traduire deux pages du journal prussien la Minerva pour moi ? Il s’agit d’un témoignage sur la harangue de Prieur de la Marne à l’armée du Centre fin septembre 1792.

Au cas où, voici le lien (la partie à traduire commence p. 173, le paragraphe qui commence “Die Armeen der Republik…” et finit avec la lettre p. 175).

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In 1913, François-Léon Sicard created a monumental sculpture for the Panthéon, known as the Autel de la Convention Nationale or The Republican Altar [...]. Tellingly, it was not dedicated to the glory of any one man, but to the deputies as a collective. The Republic is personified as a woman and stands at the center. To one side are deputies swearing an oath of loyalty to the Republic: they include Robespierre, Danton and Desmoulins. On the other side, amongst soldiers of the Republic, is a deputy en mission, in military mode, on horseback – Saint-Just. It had taken 119 years, but they had finally achieved the public acknowledgement of a heroic identity, through the apotheosis of the Panthéon.

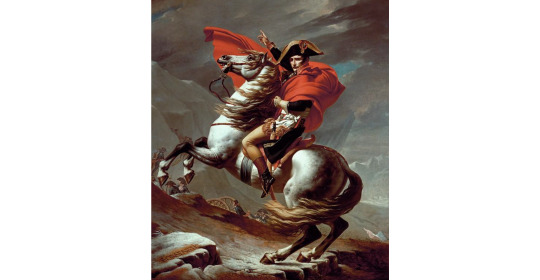

The fall of Robespierre began a period of transition between the politics of virtue and the politics of glory. Both Saint-Just and Robespierre had warned of the possibility that the escalation of the war and the growth of the French armies might see the emergence of a Julius Caesar rather than a Cincinnatus. Such a man would base his public image not on self-effacing political virtue, but on the traditional military qualities of courage, leadership, and glory. A short distance from the Panthéon stands Les Invalides, within which rests the monumental tomb that commemorates just such a man: a man who did not shrink from taking power in his own hands. Napoleon Bonaparte proved himself not only adept at exploiting the language of the ‘man of virtue’ when it suited his purposes, but also, when the opportunity came, prepared to seize the moment to emerge as France’s ‘man of glory’.

Virtue or Glory?: Dilemmas of Political Heroism in the French Revolution by Marisa Linton, p. 100f.

119 notes

·

View notes

Photo

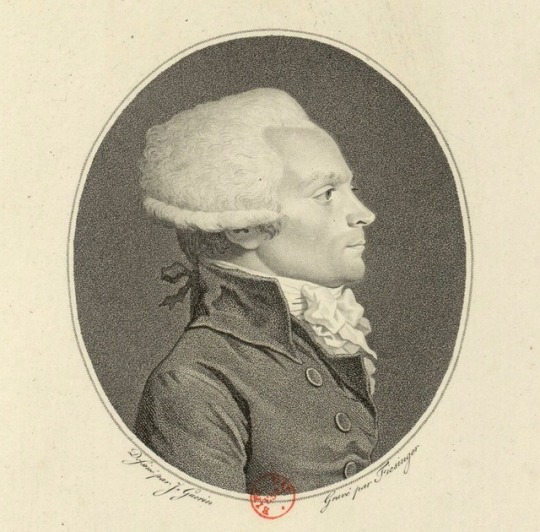

Robespierre’s conception of the patrie

The patrie is not, for Robespierre, a geographical place, or a territory, or a country. The patrie is where the natural rights are, it is above all in the natural law that governs the world and humankind, the patrie is in the flesh of the human being, it belongs to the being, as he explained on 5 February 1794:

What is the goal that we aim for? The peaceful enjoyment of liberty and equality; the reign of eternal justice, whose laws have not been inscribed in marble or on stone, but in the heart of all men, even in the one of the slave who forgets them and of the tyrant who denies them [...].

As we see, the natural law is ... naturally inside the being, an animal of nature, prior even to the awareness of it. Man is made to live freely. Here, we encounter the postulate of the philosophy of the droit naturel, assuming its anteriority compared to [...] any human construction. The patrie is where this reciprocal droit naturel is realised. [...]

The patrie is also the cause of humankind, fighting to restore the universal droit naturel against those who oppose it, as he said in his response to Louvet on 5 November 1792:

The family of the French legislators, that is the patrie; it is the entire human kind, minus the tyrants and their accomplices [...].

Thus, the revolution in France is but a stage in a universal movement of the reconquest of the natural rights:

One could say that the two opposed geniuses that one has represented fighting over the control of nature are fighting in this great age of the human history in order to set the future of the world irreversibly, and that France is the stage of this formidable fight [...].

On 5 February 1794, Robespierre defined patriotism as the love of equality:

But since the essence of the Republic or of democracy is equality, it follows that the love of the patrie necessarily embraces the love of equality [...].

Equality is the reciprocity of liberty. Robespierre here emphasises the universality of the droit naturel. [...] The patrie is both the starting point and the destination: it is in the hearts of all humans as the characteristic of humanity, it will be realised at a universal scale through the process of the revolution of the droit naturel itself, going through different phases: awareness, understanding, reconquest through the re-establishment of rights and of the law, realisation by its application. In short, it is the revolutionary process itself, fighting against the enemies of the droit naturel.

Triomphe et mort de la révolution des droits de l’homme et du citoyen: 1789-1795-1802 (Florence Gauthier), p. 170-172.

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In 1796, Jean-Baptiste Chemin-Dupontès, printer and editor, attempted [...] to organise a cult reintroducing the sacred as taken up by the cults of Reason and of the Supreme Being that had developed spontaneously in the first years of the Revolution. He expounded the project of this “reasonable” religion, which strove to replace Catholicism, in his Manuel des théoanthropophiles ou adorateurs de Dieu et amis des hommes, contenant l’exposition de leurs dogmes, de leur morale et de leurs pratiques religieuses, avec une instruction sur l’organisation et la célébration du culte. With Valentin Haüy who joined him, he organised a cult, private at first, which became public and assumed the name of theophilanthropy. The latter acknowledged a natural order of divine origin, from whence stemmed the duties of man towards his fellow beings and the Patrie. This cult, which is a means to encourage virtue, does not address God, but “men need to remember this witness of their action in order to mutually encourage each other to do good”. There was a domestic cult and a public cult. The former began after waking up with an invocation to the “Father of nature” and ended with an examination of one’s conscience. Between these two rituals, the theophilanthropist should have lived modestly and done good. The latter took place in front of an altar decorated with fruits and flowers, the “good deeds of God”, while the theophilanthropists were engaged “in the joy of being in communion in noble thoughts”. The dogma was resumed by five inscriptions that surrounded the altar: “We believe in the existence of God, in the immortality of the soul”; “Love God, cherish your fellow men, make yourself useful to the patrie”; “The good is everything that aims to preserve man or to perfect him. The bad is everything that aims to destroy him or to deteriorate him”; “Children, honour your fathers and mothers. Obey them with affection. Alleviate [their sorrows] in old age. Fathers and mothers, educate your children”; “Women, see your husbands as the heads of your households. Husbands, love your women and make each other happy”.

Le Directoire. La république sans la démocratie (Marc Belissa / Yannick Bosc), p. 179f.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

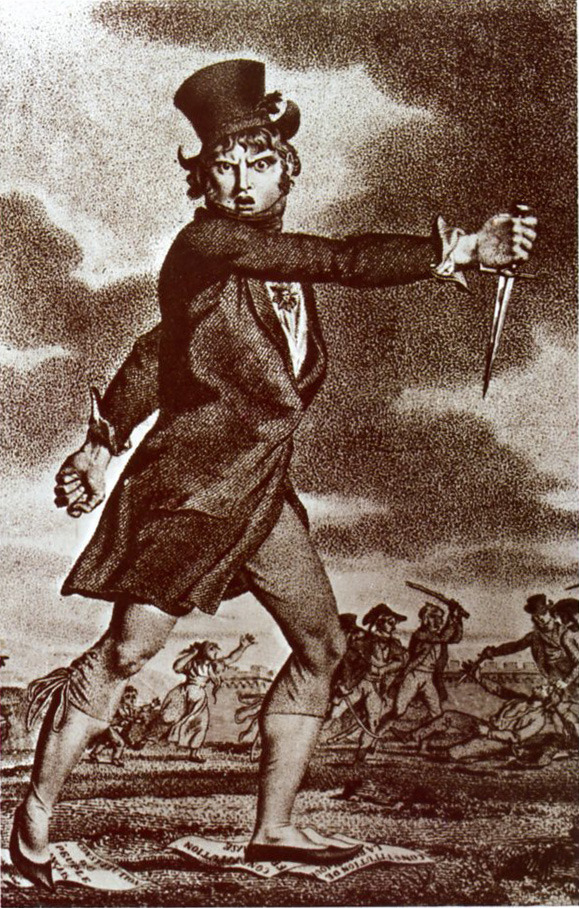

The decree of 10 January 1795 authorised the return of the émigrés that “worked with their hands” and who had left France after the journées of 31 May - 2 June 1793; the one of 21 February 1795 permitted the reopening of churches and the return of refractory priests (i.e. priests who were hostile to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy that had been adopted in 1790) if they accepted the oath of fidelity to liberty and equality. Two days later, the officials that had been deposed or suspended on 9 Thermidor were put under house arrest. At the end of the winter, the “White Terror” that was carried out by the royalists against the militants of Year II intensified. In the Midi, in the fort Saint-Jean in Marseille, in the fort of Tarascon, in the prisons of Aix-en-Provence, of Arles, of Lyon where one hunted down the “mathevon” (i.e. the sans-culotte), the “patriots” were murdered en masse. The armed royalist gangs, such as the Compagnie de Jéhu or the Compagnie du soleil, multiplied their punitive expeditions against republicans or constitutional priests who were massacred with complete impunity, the local authorities often being accomplices.

Le Directoire. La république sans la démocratie (Marc Belissa / Yannick Bosc), p. 32f.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If today, no specialist can make the Revolution end with the death of Robespierre – as Michelet did –, there is no doubt that a political rupture occurred in the months that followed. The so-called period of the Thermidorian Convention, which stretches from 11 Thermidor Year II (29 July 1794) to the establishment of the Directory on 4 Brumaire Year IV (26 October 1795), saw the emergence of a discourse that legitimised the rejection of the Constitution that had been adopted on 24 June 1793 (and ratified by the primary assemblies on 9 August), and more generally of the democratic Republic of Year II that one associated with the “Terror” and with the “tyranny” of “the deliberative anarchy”, to use the Thermidorian vocabulary.

The purification of the Convention of most of the Montagnards, combined with the return, at the start of Year III, of the deputies that had been excluded in the aftermath of the Revolution of 31 May / 2 June 1793, brought about a brutal swing to the right of the Assembly. The (sometimes physical) elimination of the political personnel of Year II on account of “terrorism” of “Robespierrism”, the liquidation of a great part of the democratic and social legislation that had been adopted in Year II, the progressive dismantlement of the institutions d’exception of the revolutionary government provoked a political “reaction”, facilitating the apparition of the “White Terror” which struck the republican personnel in most of the departments.

The repression of the Parisian popular riots of Germinal and Prairial Year III, demanding “bread and the Constitution of 1793″, facilitated the process which resulted in the introduction of a new Constitution, which was adopted on 5 Fructidor Year IV (22 August 1795), re-founding the republic on a confiscation of the exercise of sovereignty by the “honnêtes gens”, i.e. by the owners, as the deputy Boissy d’Anglas affirmed on 5 Messidor Year III (23 June 1795).

Le Directoire. La république sans la démocratie (Marc Belissa / Yannick Bosc), p. 14f.

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A denial of circumstances implied obviously a genetic cause inherent to the “revolutionary idea” and the presence of ‘93 in ‘89. In its most vehement renditions, this thesis had traditionally been the appanage of the far right. At the end of the nineteenth century Senator de Poriquet declared that “July fourteenth was the beginning of the Terror.” Evoking “the festival of murder,” Taine suggested much the same thing. In the 1930s, Léon Daudet reminded Maurrasians that “the vile fourteenth of July” was the “veritable start of the terrorist period,” a view that became a canon of the Action française. In the bicentennial period, this idea was still very much a leitmotif of the far right. Citing Antoine Rivarol, the Lepéniste daily Présent credited Bastille Day with launching “the cycle of useless destructions and atrocious slaughter:” “The Terror began in 1789,” noted a correspondent of the Anti-89. A kindred journalist in Valeurs actuelles breathlessly discerned the horrors “in embryo” during the ostensibly “happy springtime” of 1789.

Thanks largely to Furet’s skillful reformulation of the connection between ‘89 and ‘93, however, took on a more moderate cast. Bridging the far right and the so-called civilized right, Figaro-Magazine made it the backbone of its bicentennial line: the Terror was an “extension” of ‘89. In a book contrasting the French and American Revolutions [...] Georges Gusdorf embellished the revisionist line that “1789 carried 1793 in embryo.” Furet never pressed the argument to its ultimate stage, and this is what distinguished him and the self-styled moderns of the right who followed him (Jean-Marie Benoist, even Philippe de Villiers) from their extremist ancestors. Tainted but not utterly cankered, ‘89 still offered much to praise despite its powerful latent potential for self-subversion. Given the center/liberal reluctance in France to throw out the baby with the bathwater, especially in front of an international audience, it is not surprising that the most extreme expression of the revisionist ‘89-’93 contamination theory during the bicentennial period came from outside the country. It was all the more striking because it emanated from the pen of an Irish public figure and philosopher reputed for his sobriety, Conor Cruise O’Brien. “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” he wrote, “was in practice a mandate for Terror as long as the French Revolution lasted.”

Farewell, Revolution: The Historians’ Feud, France, 1789/1989 (S. L. Kaplan)

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In their book Robespierre. La fabrication d’une mythe, Marc Belissa and Yannick Bosc analyse how Robespierre’s image in historiography and popular culture evolved and changed within more than two centuries. After examining how the royalists of the Action française demonised Robespierre as a a ruthless proto-Bolshevik in the 1920s, Belissa and Bosc note that, on the contrary, there were also certain nationalist and anti-parliamentarist currents that invoked Robespierre as a hero.

Henri Béraud [1885 – 1958], xenophobe and militant antisemite, condemned to death after the Libération and pardoned later, was also among them. Yet, when Mon ami Robespierre appeared in 1927, Béraud had not yet moved to the extreme right. He did so following the great demonstration of 6 February 1934. [...] The narrator of this novelised biography is an imaginary childhood friend of Robespierre who begins to write down his memories. This fiction gives the author the opportunity to advance a very free interpretation of the conventionnel’s political ideas: in Béraud’s work, Robespierre sometimes resembles the prototype of Mussolini, whom [Béraud] has encountered several times in the 1920s, and for whom he does not hide his sympathy:

Maximilien wore a mask; a feigned impassibility served his plans as much as a certain use of demagogy. In reality, this man with a sensible heart only obeyed higher reasons. He cherished liberty, but profoundly hated moderation in the government of peoples, what one currently calls « liberalism », and which was in his eyes nothing but a hypocritical and cowardly form of anarchy. Enslaved by the Contrat social, he certainly believed, in the secret of his conscience, that one has the duty to interrupt the power of the laws, when it was a matter of national safety. He certainly believed that it would take many years until democracy would be possible in France, and like his master Rousseau, he believed that in order to increase the activity of the government, it was necessary to concentrate it in one or two members.

After having refuted the « stupidities » that one has, according to him, written on the political thought of Robespierre, salvaged by all, from the monarchists to Buonarotti, Béraud writes:

He was a man of order; he believed in the necessity of a society built like a pyramid, and would never have accepted the destruction of social hierarchy. Prejudices of his century, one might say? I respond that Maximilien was not one to yield anything. That if one examines his attitude in the aftermath of the insurrections, I would say that he saw in the popular convulsions a means, not an end.

Robespierre. La fabrication d’une mythe (Marc Belissa / Yannick Bosc), p. 208f.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Given [Michel] Vovelle’s position as scientific coordinator of the bicentennial [i.e. the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution in 1989], he could not afford to herald any lack of resolve on the so-called objectivity question. Nor could he allow François Furet to capture the terra firma of scholarship and relegate his adversaries to the boggy ground of ideology. Yet he revealed himself to be torn about how to articulate the relationship between vie scientifique and vie militante. Both the nature of the bicentennial issues and the stakes involved made it hard to segregate the two impulses. An important part of Vovelle’s evangelism, after all, turned on the idea that reflection on the French Revolution “is not merely an academic or school exercise.” [...]

Since “the Revolution today is still an object of battle” and “of pertinence,” it was bound to elicit very strong feelings. Indeed, to make his case for exceptionalism [...] Vovelle contended that France remained deeply divided over the Revolutionary heritage / message / mission. [...]

In the same vein, Vovelle was forced to argue a position that worried most historians – that “objectivity” and “fervor” were not incompatible. [...] Indeed, as far as the history of the French Revolution was concerned, they were perforce complementary, for there was a “civic dimension in the history of the Revolution” that morally had to be put “in the service of the republic”. Thus, [...] celebration went hand in hand with commemoration, somehow without sacrificing or blemishing the critical purview without which the historian had no legitimacy. Since “the terrain of study of the Revolution carried a ‘plus’ that went beyond its properly scholarly dimension,” it apparently allowed for a certain derogation from the standard rules. Thus Vovelle situated “his action” in the “lineage” of Alphonse Aulard’s aphorism, “To understand the French Revolution, one must love it.” [...] In Vovelle’s analysis, the Revolution was alive, hot, beloved, somewhat jealous and mercilessly maligned.

Farewell, Revolution: The Historians' Feud, France, 1789/1989 (S. L. Kaplan)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In his article Genocide and the Bicentenary, written in in 1987, the Irish historian Hugh Gough offers a lucid analysis of the politico-historiographical situation just before the Bicentenary, and of the political enjeux of the historiography of the Revolution.

If, as [Jean-Clément] Martin suggests, much of the character of the Vendée revolt was determined by the politics of the terror, then its role in current controversy is partly the result of contemporary politics. The revolution remains a potential dividing point in the politics of modern France, and its interpretation is still in dispute. Many of the themes in the current controversy can be traced back to the reaction against the domination of the Marxist interpretation set in train by Alfred Cobban and Francois Furet during the 1960s. Yet that interpretation itself has become more pluralist in the intervening years, as the originality and variety of Michel Vovelle's publications and of recent editions of the Annales historiques de la révolution française show, and it is the new integralist right which has taken on the mantle of a shrill orthodoxy. Furet himself has condemned as "une absurdité” the right's attempts to use his own ideas “pour mettre en cause l'ensemble du processus révolutionnaire”, and attributed it to the new found strength of the extreme right over the last decade. Whatever the future holds for the right in political terms – and it is worth noting that the phrygian bonnet still features prominently on the flag of the [Rassemblement pour la République] – it is doubtful that its attempt to re-write the history of the revolution will have any lasting impact. A recent opinion poll, in early February 1987, found that 75 per cent of French people thought that “les révolutionnaires de 1789 ont bien fait de vouloir changer le système politique et social de la France”. The celebrations for 1789 will therefore probably be widely popular, although for differing reasons, while the fireworks in 1993 will be decidedly damp. The real danger, however, is that the revival of polemic as a means of scholarly exchange may have the regrettable result of sucking all debate on the revolution into a new cold war. If that happens, both history and the historians of the French Revolution will be the losers.

Genocide and the Bicentenary: The French Revolution and the Revenge of the Vendee (Hugh Gough), published in: The Historical Journal, volume 30, n° 4 (1987), p. 997f.

More than thirty years after the publication of this article, it is worthwhile to reflect on Gough’s closing lines, and on how his predictions contrast with the actual events of the Bicentenary and the historiographical developments after 1989.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

work in progress: essay

In the course of my research for an essay on the (so-called) “génocide vendéen”, I stumbled upon Claude Petitfrère’s article La Vendée en l'an II : défaite et répression, which deals with the last phase of the war in the Vendée. After arguing against the application of the term “genocide” to the repression in the Vendée, Petitfrère goes on to explore the complex enjeux of this term:

The way that we call things does not change anything about their reality. So, why fight over a matter of vocabulary? Because, surely, words are not innocent, especially the anachronistic term « genocide », due to its historical, emotional and symbolical load. Some people act as if the battle was not about the reconstruction of past events, or the understanding of them, but about the defence of a philosophy, of an ideology, about the use of historians and of their certainties, in a way, rather than about history. The intention seems evident in this phrase of Pierre Chaunu: « the Jacobin dérive appears today as nothing more than the first act, the foundational event of a long and bloody series, which goes from 1792 to our days, from the génocide franco-français of the Catholic Ouest to the Soviet gulag, to the destructions of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and to the Khmer Rouge auto-genocide at Cambodia […] ».

It is not hard to see where this leads. Morally condemning the First Republic, the Revolution in its totality, even the « Enlightenment », considered as a homogeneous bloc, it is a matter of discrediting all those who, from nearby or from afar, invoke the principles of ‘89 […].

La Vendée en l'an II : défaite et répression (Claude Petitfrère), in: Annales historiques de la Révolution française, n° 300 (1995), 184f.

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

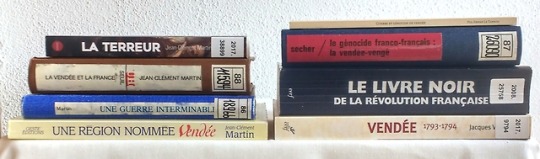

During my research for an essay on the war in the Vendée and the historiography that has come to surround it, I stumbled upon a very ... peculiar book: Le livre noir de la Révolution française, published on 21 January (!) 2008. Instead of attempting to write something elaborate on this publication, I will content myself with quoting Hervé Leuwers’ introduction to his review of it.

There are books of which a journal dedicated to scientific research and debate should not speak; Le livre noir de la Révolution française is one of them. But it can be found on bookshop stalls, it appears in the press and on websites... The title, the date of publication (21 January) and the content do not leave any doubt, and every historian, every informed reader, will be quick to understand its nature and to react with anger or scorn. If it was only a matter of ignorance on the part of the authors, or of a coup commercial by the editor, no doubt, silence would impose itself; but when manipulation mingles with supposedly historical discourse, silence is no longer appropriate.

Hervé Leuwers’ review of Le livre noir de la Révolution française (2008), published in Annales historiques de la Révolution française, n° 351 (2008), p. 225.

In case you are interested, I highly recommend reading Leuwers’ full review.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

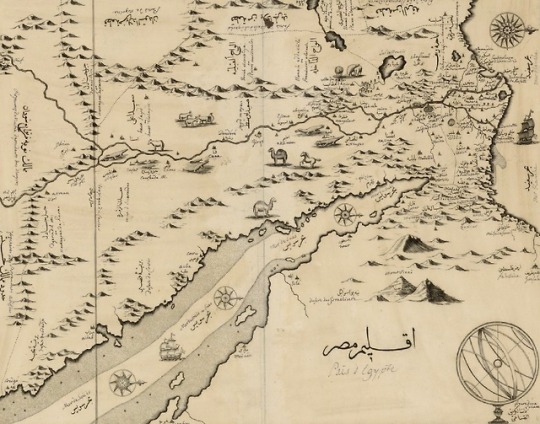

[In Egypt,] the revolutionary upheaval did not long remain just a distant clamor from metropolitan France. By 1790, the French consul in Alexandria was complaining about a “plague of insubordination and licentiousness” spreading through the French extraterritorial communities. Visiting sailors brought with them a fierce attachment to the Revolution, insisting that all French subjects don the revolutionary cockade. In 1790 the sailors revolted en masse against their captains. Jacobins in the Échelle began to call for the abolition of the whole consular regime in the Levant, as a reflection of royal tyranny and privilege. The situation became further embittered as members of the consular staff began to “emigrate,” taking refuge with the British or Austrian consuls. In Cairo, the radical faction purchased weapons and formed a “national guard” that met everyday. These Jacobins even sought permission from the authorities to build a temple of Reason. But [the regent of Egypt] Ismael Bey, the protector of the French, died suddenly during an epidemic in Cairo in 1791, and his rivals Ibrahim and Murad returned in force from Upper Egypt.

Egypt in the French Revolution (Ian Coller), in: The French Revolution in Global Perspective(edited by Suzanne Desan, Lynn Hunt, William Max Nelson).

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Revolutionary rights talk inspired both women and free people of color to stake their claims to political participation. The cultural work of the Revolution – embodied clearly in the night of August 4, when the National Assembly abolished the privileges associated with nobility – produced a transnational logic of equality. An October 1789 text addressed to the National Assembly drew attention to women’s continued oppression: “You have broken the scepter of despotism; you have pronounced the beautiful axiom [that] ... the French are a free people. Yet still you allow thirteen million slaves shamefully to wear the irons of thirteen million despots!” As the most extreme form of the denial of rights, slavery here served as an analogy for the legal subordination of wives to their husbands. [...] At the end of the petition was a list of proposed decrees, the first of which referred to the August 4 decrees: “All the privileges of the male sex are entirely and irrevocably abolished throughout France.” A delegation of free men of color submitted a similar demand to the National Assembly in October 1789, arguing that they deserved full equal rights as well. The National Assembly did temporarily grant citizenship rights to free men of color in 1791, in the hope that they would help put down slave riots that had broken out in Saint-Domingue, but any attempt to dismantle slavery remained off the table. As unfree human beings, slaves were by definition ineligible for the rights of citizenship. The various revolutionary constitutions likewise defined women, along with children and domestic servants, as dependent beings, whose political voices would be incorporated into the rights and privileges granted to men, whether their fathers, husbands, or masters.

Feminism and Abolitionism: Transatlantic Trajectories (Denise Z. Davidson), in: The French Revolution in Global Perspective (ed. by Suzanne Desan, Lynn Hunt, William Max Nelson).

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

24 August 1792. Two weeks earlier the monarchy had been overthrown. Within the last week, General Lafayette had defected, the Prussians had invaded, and the fortress town of Longwy had just fallen, though Paris did not yet know. In the midst of this ferment, the playwright Marie-Joseph Chénier led a delegation of Parisian citizens to the bar of the Assembly, petition in hand. He urged the deputies to offer full French citizenship to a list of “courageous philosophers who have sapped the foundations of tyranny.” The Legislative Assembly [...] took time for a hot debate of Chénier’s proposal. Two days later, eighteen foreigners – ranging from British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson to writer of the United States Constitution James Madison – were pronounced French citizens, with full political rights.

Certainly, this act was meant to play on the cosmopolitan stage of the Enlightened public sphere of Europe. But this granting of citizenship was not purely performative of honorary. Three of the adopted citizens – Tom Paine, the Prussian Anacharsis Cloots, and the Englishman Joseph Priestley – were soon elected as deputies to the new Convention, though only the first two would serve. The decree’s supporters made the politics clear: if the republic was to be universal, it must be a global creation from the outset; the National Convention would be, in Chénier’s words, “a congress of the whole world.” This idea immediately provoked the resistance and anxiety of some deputies. “You are delivering the Convention to foreigners!” exclaimed the deputy Claude Basire at one point mid-debate. And invasion by outsiders was not the only threat. Lasource warned that the Assembly should not give away this glorious title of French citizenship so lightly. To build a republic was a fragile and controversial act. “If you set about giving this tile to those who have not asked for it, wouldn’t you risk suffering the humiliation of refusal?” [...]

On one level, the events of 24-26 August 1792 – tied to a particular political moment – show how issues of foreigners and foreign policy became entangled with domestic policy [...]. One another, broader level, this event performs crucial ideological work for the new republic. [...] Historians have largely situated the origins of republican universalism in the Enlightenment discourse of natural rights. For the French revolutionaries, “universalism” meant that the legitimacy of the nation – the very sovereignty of the nation itself – rested on the defense of universal human rights and on guaranteeing equality before the law. While some scholars have stressed the exclusionary contradictions of this ideology, others have emphasized that it also enabled various groups of people to demand rights. Republican universalism had both exclusionary and liberationist potential, and the issue of inclusion/exclusion is clearly pivotal.

Foreigners, Cosmopolitanism, and French Revolutionary Universalism (S. Desan), in: The French Revolution in Global Perspective (edited by S. Desan, L. Hunt, W. M. Nelson).

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the first months of their occupation of Egypt [in 1798], the French launched an extraordinarily ambitious program of social and political transformation, creating a central consultative body called the Diwan, composed of Muslims, Copts, and Syrian Catholics, to rule the country, with a local equivalent in each province. They began reshaping the urban fabric of Cairo and other cities, demolishing buildings, clearing boulevards, erecting bread ovens, restaurants, and theaters, dredging canals, and constructing windmills. The large body of scholars, along with at least one local participant, was immediately formed into an academy – the Institut d’Égypte – which met regularly. Its reports were printed by a press that also produced Egypt’s first newspapers, Le Courier de l’Égypte and La Décade Égyptienne. As in France, the year was divided up into ten-day weeks, marked not by religious holidays, but by revolutionary festivals. These days were celebrated in Egypt, with all the republican trappings – tricolor flags, sashes and cockades, liberty trees, and fireworks.

On the first day of Vendémiaire, Year 7 (22 September 1798), a festival to celebrate the seventh anniversary of the republic was ordered in Ezbekkiya Square, in a great field “decorated with as many columns as there are departments in the French republic, in the centre of which a pyramid will be erected with seven sides on which the names of those brave soldiers killed in liberating Egypt from the tyranny of the Mamluks will be inscribed.” The authorities “both French and Turkish” were ordered to process toward the palace of the general in chief, Bonaparte, who would appear on a platform with an obelisk, to the acclaim of the troops singing hymns and patriotic songs “to the prosperity of the French republic and the friendly republics [républiques amies].” The festival was celebrated not only in Cairo but in all the towns and villages where the French contingents were stationed. In the town of Atfiéli, the Courier de l’Égypte reported, French officers, members of the Divan, and the aga of the Janissaries gathered with a crowd of inhabitants: “The general read to the Arabs in a speech written in their language, containing an account of the principal events of our Revolution and bearing witness to the wish and hope to see these peoples enjoy the same happiness as the French, and return to their former greatness.” This was as ambitious an installation as had been attempted in any of the other territories annexed or invaded by the French at that time.

Egypt in the French Revolution (Ian Coller), in: The French Revolution in Global Perspective (edited by Suzanne Desan, Lynn Hunt, William Max Nelson).

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For many years, the dominant view held that the Revolution fostered a hardening of gender roles as the new politicized public sphere it helped to create was conceptualized as essentially male, while women were marginalized in the apolitical private sphere. More recent scholarship emphasizes how the Revolution empowered women and encouraged debates about women’s rights. Revolutionary legislation requiring equal inheritance among siblings and legalizing divorce enhanced women’s position within the family at the same time that new approaches to citizenship and nationality shaped debates all over Europe. In addition, women continued to influence public life in the wake of the Revolution, despite the conservative consensus that emerged under Napoleon. A handful of radical texts published betweem 1789 and 1793 addressed women’s political and legal subjugation and have been the subject of much historical discussion, but the actions taken by thousands of ordinary French women demonstrate that many simply took political action without questioning their right to do so. In making it possible to take such actions, and to argue that women deserved the full rights of citizenship, the French Revolution inaugurated modern feminism.

Feminism and Abolitionism: Transatlantic Trajectories (Denise Z. Davidson), in: The French Revolution in Global Perspective (ed. by Suzanne Desan, Lynn Hunt, William Max Nelson).

118 notes

·

View notes