Text

reblog and put in the tags your queer awakening (could be a person, movie, book, event, whatever).

#the film version of Chicago#all those stockings and the psychosexual tension between catherine zeta-jones and renee zellweger#I also played spin the bottle with the girls in my dormitory on a summer camp when I was about 15#though come to think of it I'd a) had a mad crush on a girl in my class well before that (looking back she was terribly dull#but she was pretty)#and made my barbies fuck each other

662 notes

·

View notes

Text

A horseshoe crab being a home to other sea creatures!

31K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), poem 85 from “The Gardener”, 1914

Translated by the author from the original Bengali. New York: The Macmillan Company.

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Landscape, Gloucestershire’, Stanley Spencer, oil on canvas, 1940.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

#prev:#please do not make me interact with children#I have no idea how to talk to them#not to mention they're loud and messy and generally annoying#I never liked them even when I was a kid#<- it me

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Striped Cotton Walking Dress, ca. 1897.

Museum of New Zealand.

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Over the past few months I’ve been lucky enough to see six Powell & Pressburger films on the Big Screen. Yes I’d seen some of them in the cinema before, but this has been a concentrated run. I wasn’t sure that A Canterbury Tale would be a fitting end - it’s not my favourite (let’s not try and put them in order, though I kind of know my four faves); it’s not got any of my absolute favourite actors in (unlike some others); and it is - even for P&P - a bit of an oddity.

But you know what, it was wonderful. In 1940, Lord Macmillan, the first wartime Minister of Information, issued a memo suggesting three themes for propagandist feature films: what Britain was fighting for, how Britain was fighting, and the need for sacrifice. P&P’s war films (and how easy it is to forget that they are ‘war’ films!) fall mainly into a mixture of the first two categories, and this is firmly in the former. It’s a hymn to Britain - well, especially to England, to Kent - Micky’s home county. A specific England though; rural, elegiac, almost pre-industrial; and here is the film’s mystical charm at work - it convinces that this England still exists, even as it is fading.

It’s another compelling performance from Portman; he’s an actor of such subtlety that Colpeper - who in other hands could have been rather one dimensional - is incredibly compelling: he’s ambiguous, fanatical and at least faintly misogynistic, but he’s charming and attractive (without being deliberately so), has a deep understanding of the landscape, and an almost magical presence and influence on the young protagonists. He’s another of P&P’s Prospero-influenced characters. And Portman’s speech at the slideshow is one of Emeric’s finest (not something to say lightly).

The three 'pilgrims’ are refreshingly free of the constraints of an average romance (how often do you see a film with two soldiers and a pretty girl without a hint of anything other than friendliness?), which subtly justifies Colpeper’s motives. In fact, the main frisson onscreen is between Alison and Colpeper, and it’s not easily defined, but it’s very beautifully done. She affects him as much as he her, and the ambiguity is lovely.

And as well as all this there’s Sheila Sim in land girl uniform (another film where I am disappointed when the girl puts a dress back on), Dennis Price being urban(e) and louche, John Sweet doing wonders for the English view of GIs, a ton of wee scruffy boys and Esmond Knight as the village idiot. Plus the look of it - if you want lovely b/w mystical landscapes, then Hillier and Junge are your men (see also: IKWIG!) And of course, like all the best P&P films, it’s funny, serious, warm-hearted, dry, odd, romantic, and makes me faintly proud to be English, which is a rare gift indeed.

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

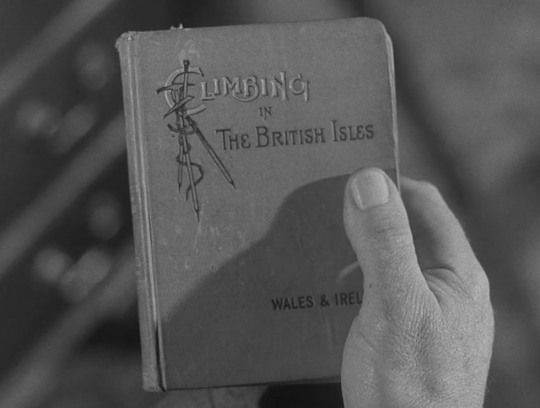

A Canterbury Tale

(1943; Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

War Starts At Midnight: The Three Wartime Visions of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger by Josh Spiegel

Few filmmakers have made films as thematically rich as those from writers/directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in the 1940s. From 1943 to 1949, Powell and Pressburger, better known as the Archers, made seven superlative films that leapfrog genres with heedless abandon, from wartime epic to fantastical romance to psychosexual thriller to ballet drama. Thanks largely to cinephilic champions such as Martin Scorsese and his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker (who married Powell in 1984), as well as home-media ventures like The Criterion Collection, the Archers’ films have received a vital and necessary second life.

While the Archers’ 1940s-era septet have recognizable throughlines as well as a reliable stable of performers, three of those films are cut from the same cloth, despite telling radically different stories with varying tones. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale, and A Matter of Life and Death all take place, at least in part, during World War II, and all three films depict a nation at war, as much with other countries as with itself. When we think of British culture, we think of the stiff-upper-lip mentality depicted in popular culture for decades, typified by how Brits acted and reacted in World War II. But the Archers, in this wartime trio, debated the validity of fighting a war with that old-fashioned mentality, offering up films designed to be propagandistic enough to be approved for release but that also asked what it meant to be British in seemingly perpetual wartime.

* * *

“But war starts at midnight!” – Clive Wynne-Candy

“Oh, yes, you say war starts at midnight. How do you know the enemy says so too?” – Spud Wilson

The nuance of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was likely always going to make it a sore spot for the British government. Colonel Blimp was not original to The Archers; he was a comic-strip character created by David Low in the 1930s, meant to skewer puffed-up elder statesmen of the British military. The stereotype of a fatheaded, pompous fool had pervaded the national consciousness so much that Winston Churchill feared the Archers’ adaptation would revive the public’s critical perception of the military when support was needed the most. But while the title invokes Colonel Blimp, the lead character is never referred to as Blimp, and is much less foolish than he may seem when initially seen attacking a young British soldier in a Turkish bath. Powell and Pressburger used the character and the staid, fusty old notions of British militarism as a jumping-off point for a detailed, poignant character study.

Set over four decades, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp begins near its finale, as Great Britain struggles to gain a foothold over the Nazis. We first see our Colonel Blimp, the portly, bald, and mustachioed Clive Wynne-Candy (Roger Livesey), beset upon by younger soldiers in the club where he now lives as part of a training exercise. Clive is infuriated because they’ve started hours earlier than planned; before the smug young soldier leading the charge can explain himself, the two get into a tussle that speaks to why Powell and Pressburger wanted to tell this story. In the production of their previous film, One of Our Aircraft is Missing, the directors removed a scene where an elderly character tells a younger one, “You don’t know what it’s like to be old.” (The idea that this could serve as the thematic backbone to an entire feature was provided by the Archers’ then-editor, David Lean.) Clive’s rage at being taken off-guard leads him to thrash young Spud Wilson and teach him a lesson: “You laugh at my big belly, but you don’t know how I got it! You laugh at my mustache, but you don’t know why I grew it!”

And so, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp flashes back 40 years, a rare instance where a movie indulging in the now-hoary in medias res technique pays dramatic dividends. The rest of the film focuses on three points in the life of the man known first as Clive Candy: his time in the Boer War, the devastating World War I, and his twilight years of service as World War II ramps up. For a war film, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp offers exceedingly little bloodshed. Powell and Pressburger’s film examines how such gruesome action informs men like Clive away from the battlefield, instead of depicting that action in full. Each section of Blimp shows how his noble efforts make him hardened and intractable over time, even against the tide of a truly tyrannical force. At first, Clive’s militaristic mantra is honorable: “Right is might.” But as the film reaches its third hour, he learns that his theory, one embodied by his nation, has been so cruelly disproven by the Nazi scourge that he and Britain must change their ways.

Keep reading

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sheila Sim in A Canterbury Tale (1944)

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Canterbury Tale (1944)

Dir. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

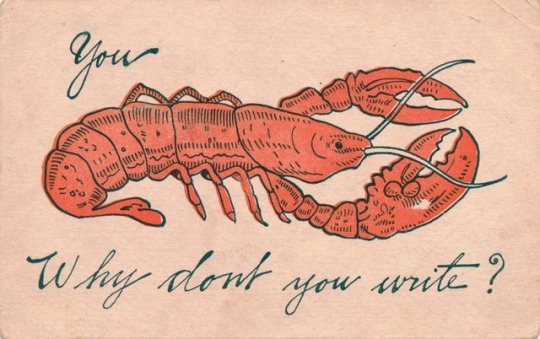

Recent Acquisition - Postcard Collection

You - Why don’t you write?

Postmarked October 1908

8K notes

·

View notes