Text

On the Beautifully Broken Boreal Tenebrae

I’m so tired of feeling broken.

I didn’t always feel this way. A sense of purpose was once a bulwark against brokenness. Going to a place every day to work alongside people I liked, feeling like part of something larger than myself, knowing that I was good at what I was doing and that I was a valuable part of the team. These things gave my life meaning.

But for some time now I’ve been adrift. I thought for sure that the work I’d done in the past would open up doors to me in the future where I would continue to be able to do work I believed in, but it hasn’t worked out that way. I sometimes feel like a useless, discarded thing, now obsolete, of use in the old world but too awkward and ungainly for the new, doomed to fall through the cracks in the level geometry and plummet through the gray void below forever. Sometimes I’m afraid now even to write, afraid that anything I write will betray my brokenness, screaming MALFUNCTION! MALFUNCTION! to anyone who reads it.

But is it me that’s broken, or is it a world that can’t find a place for me? And what happens when a whole town doesn’t know what it’s for anymore?

The new game Boreal Tenebrae (previously called Boreal Tales before being changed due to a prior claim on the title) is about a broken town, a town whose sense of purpose is turning to rot. It’s a lumber town in Saskatchewan, or at least it always has been. Now the Toads (yes, literal toads) who run the mill are talking of plummeting profits and moving operations overseas. And for some reason, mysterious blocks of static are appearing all over town.

You primarily play as Bree, a young Black woman whose sister Sarah has vanished. Sarah had a fascination with TV static. When she was younger, she’d done some “static scrying”--trying to find meaning in the snow between stations--and when the blocks of static started appearing in town, she’d returned to scrying as “a way to get to the source of our town’s sickness.” As you undertake Bree’s quest to find her sister (and possibly to save the town), you traverse the world beyond the static blocks on a surreal journey that finds you inhabiting a number of characters in a number of places, most of whom feel, in one way or another, crushed by the town’s economic collapse.

For a young man named Jessie, the terrifying uncertainty of the future looms large, and he reacts with rage to the suffocating squeeze of capitalism, taking a baseball bat to the mailboxes on his suburban street.

For Sam, forming a union seems like the only hope she and her fellow workers have, but how do you convince them to join you when they’re paid so little that they can’t risk losing the jobs that exploit them? Sam’s coworker Nicole needs to keep her job at the mill to support her uncle, whose body is broken by his years on the job and who now relies on an oxygen tank.

The Toads’ exploitation of the workers is so complete that for some of them, even being able to entertain the idea of unionizing reeks of privilege. The mill doesn’t just grind up wood. It grinds up lives. Generations of lives. The game is insightful about how keeping us in economic precarity is just another tactic the powerful employ to get working people to turn on each other as we fight over scraps, rather than letting us come together to find our collective power.

The look of the game, with its hazy polygons, is immediately reminiscent of certain PS1 games, and it’s the perfect graphical style for Boreal Tenebrae’s tone and themes. I’ve long felt that the reason psychological horror games like Silent Hill linger so effectively in our psyches is that the graphical limits of the technology of the time actually enhanced their ability to create worlds that felt ethereal and prone to collapse. The town of Boreal Tenebrae similarly feels like something caught halfway between reality and dreams. Take one step and you might fall right through it.

And indeed, like the town where it takes place, Boreal Tenebrae itself is kinda busted. It’s got lots of little grammar and spelling errors. Some cutscenes didn’t play properly for me. I once walked right off the edge of the world and had to reload an earlier save. It’s not always easy to tell where the game’s deliberately cultivated feeling of brokenness--a fractured reality, a dying town--ends, and where it just being kind of a broken game begins, and if I’m honest, I don’t really care. It all felt of a piece to me, or as if the brokenness of my life was finding its mirror in the brokenness of the game. I’m sure that falling off the edge of an environment wasn’t something the game wanted me to be able to do, and yet when it happened I just thought to myself, yep. That’s how it feels these days. Like I could just fall off the edge of the world.

I won’t pretend to fully understand Boreal Tenebrae. I’m not interested in “getting it,” and I reject approaches to art that treat stories like this as puzzles to be solved. I don’t need to make sense of how all of its vignettes fit together to know that the experience was meaningful and affecting for me, that it said something to me about my own life and my own economic and existential fears, and about how I experience the world sometimes, too: as a fragmented reality where things don’t quite click into place.

Boreal Tenebrae is, to me, a small, sharp little miracle of a game. It feels like a dream at times and then you come across a truth that cuts like jagged glass. It's unflinching and sometimes bleak but only because it wants to wake us up and make us hope for something more. In its depiction of brokenness, I found both anger at the systems that keep so many of us feeling broken, and forgiveness for myself and all of us who can’t quite figure out where we belong in a world that’s designed to grind us up.

Perhaps I should also tell you that Boreal Tenebrae doesn’t currently have an ending. It’s still being patched and developed, and right now, at a certain point, you get a TO BE CONTINUED screen. But like all the game’s rough edges, this, too, feels appropriate to me. Now is not a time for endings. We’re in a state of flux. We’re at one of those rare moments in history where we can glimpse the possibility of building something new, something better. I don’t know what the future holds for us here in reality or for the people in the town of Boreal Tenebrae, but I do know that if we’re going to create something better, where more people have purpose and dignity and live free of wage slavery and the constant fear of economic ruin, we’re going to build it together.

At least, that’s what the static seems to be telling me.

---

Boreal Tenebrae is available on Steam and itch.io, and as of this writing, is available in the Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality.

If you’re able, consider kicking me a few bucks to support my work. I could really use the help right now. Thanks.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent Medium Posts on Gone Home and The Matrix, and Being on the Bitch 50

Hi folks. A few quick updates for ya.

Recently I’ve published a few longer reads on Medium.

In October, I published The Pain of Waking: The Matrix at 20, The Stories We Tell Ourselves, and My Journey of the Self. It isn’t focused on video games, but it does make reference to Link’s Awakening, and hey, isn’t The Matrix sort of about being involuntarily trapped in a very detailed, elaborate video game?

And late last month I published House of Mirrors: How Gone Home Showed Me Myself, which Medium emailed me about to tell me that their curators “selected it to be recommended to readers interested in Gaming and LGBTQIA across our homepage, app, topic pages, and emails.” Yay!

Finally, I was chosen to be on this year’s Bitch 50, a list recognizing “the most impactful creators, artists, and activists in pop culture whose imaginations extend beyond normalizing and affirming the same mainstream messages.” Really a tremendous honor. I never thought I’d be on a list alongside the likes of Renee Bracey Sherman, Ady Barkan, Ilhan Omar, and Lizzo, but here we are. Read my interview with Marina Watanabe here.

Oh and uh, just one more thing folks. I’m currently looking for work. If you happen to know of any opportunities you think I might be a good fit for, my Twitter DMs are open.

Thanks very much, and thank you for reading!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fortnite’s Bots Turn It into a Horror Game in the Worst Sense

youtube

Fortnite’s second chapter made a powerful first impression on me. The cold open, in which I was watching what I thought was a standard welcome trailer, only to find it shifted seamlessly to gameplay when Jonesy jumped from the battle bus, was exhilarating. Sure, it may not have been the most original moment in gaming history--I was powerfully reminded of the mission in Saints Row: The Third in which you skydive from a helicopter to a penthouse below as “Power” by Kanye West plays--but the way it masked the required matchmaking to toss you unawares into the game was impressive. Pair that with my first experience of Fortnite’s new island, its vastness spread out below me, all asking to be discovered, and yeah, you’ve got something pretty memorable. That first footfall on the new island found me marveling at its picturesque beauty, loving the way the purple light of dusk can stream into a room through the window, adoring the wooden bridges I happened upon in the forest and the little cabins I saw along a lake. It felt open and inviting, more rugged and authentic than Fortnite’s previous island, yet still tinged with cartoonish magic. I was thrilled.

One day later, though, and I now feel like I’m in an episode of The Twilight Zone, the kind where the main character thinks a new place is one thing but then discovers it’s actually something else. It feels like a place askance. I’ll tell you why in a moment, but first I want to tell you about why I play Fortnite.

I don’t play Fortnite to win. Sure, I like winning, but I’m not good enough for that to be my motivating factor. Last time I checked my career stats, I think I’d won roughly one out of every 75 matches I played, and I didn’t have a very good Season X, so it’s probably worse than that now. I play in part for the world of the game. Fortnite’s first island was varied, but more than that, it was prone to changing in big and small ways without warning. Sometimes I’d just go back to a place I thought I knew and find it changed. It felt alive in this way. In flux. But what made this liveliness in the landscape matter were the encounters I had with other people all over that landscape. It’s all the infinite contingencies that can occur when you happen upon someone else that make Fortnite so exciting. In the split-second interaction of your actions and theirs, there’s a kind of heat that comes from knowing that what you’re putting out into the world in that instant is colliding with what another living human being is putting out into the world.

Now, Fortnite has introduced bots. What percentage they are in each game, I don’t know. From a distance, they look just like you and me. But their behavior is...strange. I’m not scared of zombies that stumble around muttering “brains,” but a zombie that remembers being human just enough to go through the motions of life in the most rudimentary way? Fucking terrifying.

(see an encounter I had with two bots in this tweet)

Fortnite now feels like a horror story about an idyllic island where some strange phenomenon is changing large swaths of the population, turning them into husks that only vaguely recall what it is to be human. I feel like some kind of paranormal investigator, cataloging the eerie behavior of this insidious new life form. I cross the island now and I see single walls tossed up here and there, something the bots routinely do but that’s unusual for human players. Often a single wall in a structure will be destroyed, leaving a gaping hole, where most players would have just used the door. Sometimes you’re in a place where treasure chests have been looted, and you can just tell based on what’s been picked up and what hasn’t that whoever--or whatever--opened that chest wasn’t human. This haunted feeling follows me everywhere in the game now.

Usually I know a bot when I see one. When I defeat them, I see that they have names like BushCamper or LootTrooper. But even if they are often easily identifiable, their presence saps the game of the heat I mentioned earlier which is so essential to why I play the game. Now, I score an elimination and I experience a feeling of deflation. I don’t understand what the bots are meant to accomplish. Their behavior is too rudimentary to help me be better at the game in my encounters with human players. Is Fortnite just trying to stack the odds more in my favor, to serve me a victory on a silver platter? I won’t lie; even with bots, there’s some kind of chemical satisfaction some part of my brain gets from scoring four or five eliminations in a single match, something that was almost unheard of for me when all my opponents were human. But I don’t want the game to give me these hollow ego boosts and empty victories. Yes, I’m terrible at the game. I’d love to get better, but I don’t want you letting me win just so that I can feel better. Fuck you. Give me your cold indifference. Let me flounder. Let me get crushed over and over again. It’s preferable to this.

Typically, playing Fortnite comes with some built-in paranoia. Is my hiding place really so hidden? Where is the sniper shot going to come from that eliminates me before I even have a chance to react? How badly am I going to get outplayed this time? Now I find myself contending with a different kind of paranoia. What if other players think I’m a bot? My gamertag (at least when I’m playing on Xbox), Lightrunner, perhaps seems like something that whatever algorithm that’s generating the names of Fortnite’s bots might come up with. I’m sometimes an awkward, hesitant player, short-circuiting between building and attacking, getting eliminated as I stand there with my blueprints in my hand, unable to make a decision and act. How do I show other players that I’m real? How do they show me that they’re real? How do we keep the paranoia from taking over and making us mistake each other for empty husks? How do we find our fellow human beings in the swarm so that we can feel the heat that’s only found in the communion of our competition?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Control

Toward the end of Control, there’s an exhilarating sequence called the Ashtray Maze, in which the shifting nature of The Oldest House takes center stage, becoming part of what feels like a choreographed dance, all of it adding up to a dazzling, whirling, almost staggering multimedia extravaganza. It’s a real knock-your-socks-off moment, easily the most impressive video game set piece I’ve seen since at least Super Mario Odyssey’s New Donk City Festival. Yes, I loved the Ashtray Maze, but in the hours and days since I’ve finished the game, the maze has come to feel less like an audiovisual expression of some sort of meaning hidden at the game’s heart, and more like a distraction from the fact that, in the end, there is no there, there.

Jesse Faden arrives at The Oldest House, the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Control, with a past full of mystery and a head full of questions. When she was a child, agents from the bureau came to her hometown of Ordinary to investigate an Altered World Event, a paranatural disruption of our dimension, just the sort of thing the bureau works to, well, control, its work a secret from all of us who go through our lives unaware of the strange power that certain objects and people possess. The shifting hallways of the House waste no time in ushering Jesse to the director’s office, where a man, Director Trench, lies dead. She picks up his service weapon, and with that, instantly becomes the new director, soon setting off into the depths of the House in search of answers to the questions of her past.

Or is it you, the player, who picks up Trench’s service weapon? Of course, almost all games allow us to question the relationship between the player’s actions and the actions of the character they play, but Control actively raises these questions. An entity or body known as The Board, that dwells on the Astral Plane, holds some authority over the bureau and its director, and when it speaks, words and their meanings splinter, sometimes breaking the fourth wall and making you aware that the game is addressing not just Jesse but you. Given Control’s concerns with other planes of existence and with objects that can be multiple things, initially the ways in which it also peels back the layers of its own internal reality and asks you to consider how they are constructed by game designers add a delicious added layer of seeming meaning to the proceedings. Who is in control? Me, or Jesse? The Board, or the folks at Remedy who made this game? Is there even a meaningful distinction here between the Board and Remedy?

youtube

There are pleasures aplenty to be found in The Oldest House. Scattered everywhere are memos and reports on events, objects, and phenomena that the bureau has cataloged and investigated, and in truth, I’ve never before found in-game text quite so fun to read. I mean, I may appreciate in the abstract that someone had to write all those in-universe books cluttering up every bookshelf in Skyrim, but I’m sure as hell not gonna take the time to read them. In Control, though, I stopped to read every memo I found, always game to read about some other strange object or bizarre happening. And then there are the charmingly off-kilter, official bureau short films hosted by Dr. Casper Darling (Matthew Porretta), whose sparkly-eyed enthusiasm for the phenomena he studies is infectious. Darling’s one of the few sources of any real warmth or humanity in the game, and while it’s certainly welcome whenever you come across it, the chilliness of most of Control ends up being to its detriment.

As you make your way through the labyrinthine halls of the bureau, you’re routinely besieged by groups of agents corrupted by something called the hiss. With your service weapon and the abilities you acquire from some of the strange “objects of power” the bureau has acquired, you dash around environments (and later levitate), popping off shots and hurling objects, a superhero with a gun. The combat is speedy, chaotic and kinetic as all hell, and definitely wants you to feel like an unmitigated badass. It works, too. I just wish that among all the questions Control was interested in exploring, one of them was about whether or not it’s such a good thing that games so often want to make us feel like the only one capable of fixing things, the only one who really matters. Or how about this: Why is a game whose narrative is so concerned with the strange and unconventional mechanically interested in providing us with only the most conventional, ordinary types of enjoyment that games so often aim to provide?

But in the end, it turns out Control isn’t really interested in exploring questions much at all, despite pretending to be in the beginning. I hoped the final few hours might contain, if not answers exactly, then at least some sort of meaningful suggestions toward possible answers. But they don’t. It all falls apart in a mess of rapid-fire events and revelations that don’t actually reveal anything. Haven’t we realized yet that “mystery box” storytelling isn’t any good if the box is ultimately revealed to be completely empty? Control could have been well-served by a commitment to saying things, even too many things, so that the truth or meaning was like one of the game’s objects of power, looking different from each angle or shifting so rapidly that the human eye couldn’t perceive it. But no, there’s nothing there, just smoke on which is projected the illusion of something, which might be enough for YouTubers to create speculative fan theory videos about “what it all really means,” and they’ll all be right and they’ll all be wrong, because Control can’t commit to actually meaning anything. That’s not enough to undo Control, because when you have as much style as this game has, it turns out that style is enough, but only just.

(6/10) (Recommended)

16 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The great new game 198X is all about the deeply personal relationships the main character, Kid, has with the games that they play. My new video is about 198X, how this game and many other games have meant something to me, and how so many of us who play games sometimes find deeper meaning in the experience.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reason to Play, a Journal--Entry One: Fortnite, MGSV, and Finding Ourselves in the Act of Play

Hi.

This is the first entry in what I hope will be an ongoing journal of play. I wanted to start by explaining my thinking behind this project.

Right now, I’m looking for a reason to play. I’m always wary of games that seem to offer nothing beyond a mildly pleasant occupation of my time, and right now, I find such games downright inadequate. Unworthy. These are horrifying times, and yet, like so many of us, I find myself exhausted by it all. Unable to maintain the levels of rage and resistance that the actions of the current administration demand. I see it all becoming normalized and I feel powerless to stop it. And as the days and weeks and months go by, I feel as if this numbness accrues. I become increasingly detached, not just from the horrors of the moment but from myself. I start to wonder where the person I believed myself to be has gone.

I believe that art is most vital in times like this. I love this quote from Kafka:

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we're reading doesn't wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for?...We need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.”

If a game isn’t going to be the axe for the frozen sea inside me, if it isn’t going to cut through the numbness, shake me up, break my heart, fuck me up, do something to rehumanize me, it is not worthy of this moment.

But I might find what I’m looking for anywhere. I’m not talking just about games that explicitly comment on fascism or racial injustice or economic inequality. Yes, I think it’s essential that we have art, including games, that confronts these things directly, but it’s also true that a game can have the noblest aims and leave me cold, while a throwaway moment in a big-budget mainstream game of the sort that certain gamers like to call “apolitical” can crack my heart wide open.

Like most of my writing about games, this journal will be a place where I fully embrace the subjectivity of my own experience with the games that I play.

Okay. Here we go.

Testin’ My Mind, Shakin’ My Body in Fortnite

Yeah, okay, Fortnite’s a Battle Royale. That’s just a fact. If you’re playing solo, which I almost always am--I’m uncomfortable teaming up with random players, though on occasion I’ll play duos with a friend, which makes for a completely different, really exciting dynamic--you drop onto the island with close to a hundred other players, and the way you win is by being the last player standing. Now, I encourage conversations about the violence inherent to the format, as well as about all the other aspects of Fortnite that people rightly raise concerns about--the way in which it’s monetized, Epic’s pattern of repeatedly profiting off of dances associated with artists and communities of color without compensating the artists or communities that created them. All of it. But if we’re gonna go to the mat with Fortnite on these aspects (and we should), let’s also at least have a full, multifaceted conversation about why we play Fortnite, how it feels, and the moments that can emerge from a fully invested experience of the game.

Did you know that earlier this year, a massive beast that had been frozen in ice under Polar Peak broke free, that huge footprints showed it had made its way to the sea, where it’s occasionally been spotted, roaming the waters around the island? Did you know that right now, a towering robot is being built in the remnants of the volcano? It seems inevitable that soon, a massive Pacific Rim-style fight between them will take place, almost certainly resulting in a new wave of major changes to the island. Indeed, the island is always a place in flux, changing in big and small ways. It’s alive in ways that I’ve always wanted my game worlds to be alive. Landing near Loot Lake a few weeks ago, I was excited to see that the massive power cable that runs through the area was shredded and sparking, as if perhaps the monster had taken a bite.

But the life of the environment wouldn’t mean much if it weren’t for my encounters with the lives of other players. The other day, I was trying to complete a challenge that required me to get a certain score on a balloon board at one of the numerous little beach party setups that currently dot the map. Jumping from the bus, I swooped down to a spot in the desert, opened a chest, grabbed the weapon, and made my way over to the nearby board. Another player got there just before me, and I stood still, hoping to indicate that I didn’t want to stop them from completing the challenge. They froze for a moment, but then proceeded, and when they hit the necessary score, a little celebratory explosion of confetti occurred, and I got credit for the challenge, too.

Basking in the glow of our shared little moment, I wanted to walk away then, wishing them nothing but the best in the match ahead. But then they took a shot at me. In that instant, a sinking feeling ran through my whole body, a physical expression of “Aw, why’d you have to go and do that?” and in an instant, I obliterated them. It wasn’t a victory. It was more like putting someone down. I didn’t feel good about it, but it sure was a real feeling. Something surprising and immediate that emerged from my encounter with another living person. And that’s what I’m here for.

Yes, Fortnite is a Battle Royale, but so much of the experience of Fortnite is about unexpected occurrences like this, and about the things we do in the stolen moments between the shootouts and build battles. The other day, I got so caught up in playing a silly memory game I stumbled upon that I wound up getting caught in the storm. Not long before that, I danced with John Wick to raise a disco ball in an abandoned lair so we could snag a fortbyte, one of this season’s collectibles. These are the things I really remember, not my win-loss ratio or all the times I’m eliminated by players much better than I am before I quickly hit play and hop on the battle bus all over again.

I’m eager to return to the island because the island itself feels vibrant and alive, emanating a kind of Spielbergian Americana and optimism, but also because of the vigorous bodies and exuberant identities I get to inhabit while I’m there. The mix-and-match nature of Fortnite’s customization means that one round I might be a sprightly female wizard with a sleek laptop on her back, and the next a nerdy, purple-haired gamer girl with a satchel full of potions and spellbooks. “Fun” may be overemphasized in some of our conversations around games, but it certainly has its place, and playing as these colorful characters, well, it’s just fun.

Every character in Fortnite plays exactly the same, but they don’t all feel the same to me. I just unlocked a black variant of the character Sentinel, a robot or power suit that looks like it might have appeared on Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers, and I think it looks kinda cool, but I sure don’t want to be it. On the other hand, playing as Elmira (pictured above) feels good. And oh, do I love the way that some emotes make me feel. Tweeting recently about an emote called the Laid Back Shuffle, I wrote:

I’m almost always pretty uncomfortable in my body, for a number of reasons related to my appearance and my transness and things. The easygoing physical exuberance of this emote, the way that the avatar performing it, whatever avatar that might be at any given moment, appears to feel so loose and free in their own body, makes it really appealing to me, like a virtual experience/expression of a sensation that I’ve never known IRL. I think emotes have some kind of power beyond whatever power we often think of them having, perhaps particularly for those of us who never really feel comfortable in our own skin.

And all the kids playing Fortnite that we’re so worried about, let’s remember that their experience of this game isn’t as simple as just trying to slaughter everyone else on the island. Setting aside whatever value there may be in the particular type of complex thinking and skill-building that it requires to try to simultaneously outbuild and outgun your opponent, there’s also the fact that they, too, are experiencing the life of Fortnite’s island, having encounters with other players that play out in unexpected ways, and experimenting with self-expression. Yes, their opportunities for that exploration and expression are gated by money, and that’s a real issue, but that doesn’t change the fact that a young person finding that they feel particularly cool when playing as a woman in red with a bionic arm is valid, and maybe even valuable.

II. MGSV and What I Know Is True

I set The Phantom Pain aside for a few years after hitting a mission that I found maddeningly difficult, but something called me back to it. Now I’ve powered through the mission that gave me so much trouble, and I’m making progress again. I enjoy the geographical roughness of its environments, and the way you really have to deal with that roughness, often lying flat and crawling along the ground. The truth is that I spend far too much time alone in my apartment, and though it’s no substitute at all for the real, natural world, when I take my time being rooted in one spot to scout out locations and tag enemies before making any dangerous moves, I feel the shape of the space around me in a way that I rarely do in games.

The other day I fought a grueling boss battle and then, finally, when it was over, hopped onto the helicopter to return to base, exhausted by the ordeal. Just as we were about to lift off, Quiet hopped on, hanging off of the side of the chopper as the rotors above her head spun faster until we lurched up and away from the ground. She held my gaze the whole time. I think a lot of games look at the player too much. They want you to feel like the center of the universe, the only person who really matters. But that wasn’t the feeling I got from this moment. I’d just fought for my life, and the way she looked at me, without malice or sympathy for what I’d just been through or anything, made me feel like I was being sized up. Looked at in a real way. Seen.

Do you know that feeling--Does this happen to everyone or just me?--that feeling where, for a moment, your awareness kind of spreads beyond yourself and you’re suddenly very aware that what you’re experiencing is something real that is happening in physical, three-dimensional space at this exact moment in time? It’s a feeling I get sometimes when I’m in a moment that I wish I could make last, or that I really want to remember. Sharing a last drink with a friend before they move away, that sort of thing. This feeling of momentarily being very much rooted in myself but also outside of myself and acknowledging, This is real. This is something that happened. That moment where Quiet was looking at me in the wake of the momentous battle I’d just fought felt something like that.

It didn’t happen in real, physical space, but virtual space is a valid space, too, a space where real things happen. Sometimes when I’m playing Fortnite I’ll see the hillside where a friend and I once sped away from attackers on a Quadcrasher, bullets whizzing past our heads, and I’ll think, We were there. That happened. These moments become part of my relationship with the ever-changing island, just as my memories of San Francisco become part of my relationship with the city.

On another recent mission, I was sneaking my way through an enemy outpost when, from a nearby building, I heard the familiar sounds of Spandau Ballet’s “True.” To be honest, I never liked “True” much. The Phantom Pain takes place in 1984, and as a kid in the suburbs of Chicago in that year who sometimes saw the video on MTV, the song felt too airy and ethereal to move me. But recontextualized in The Phantom Pain, I heard it differently. That precise ethereal quality made it such an effective contrast to the grim military seriousness and the tactile terrain that my heart began to ache.

The presence of 80s pop songs in the isolated military outposts of the game is politically fascinating to me. It says something about how American and British cultural exports are absorbed by the entire world, but it’s largely a one-way street. A Pakistani friend of mine in high school had grown up with Sting, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis, but I’d never heard Pakistani music in my life. I don’t understand why so many players are so intent on not considering all the political dimensions of a game like this. They only make the experience infinitely more fascinating, even if and when they reveal the game’s failures.

The songs also allow for the creation of some great moments. I snuck into the building where the song was playing just so I could snag the tape, and the next time I was in the helicopter, I played it, and as the opening notes of “True” played, I panned the camera slowly around Big Boss, creating a very short music video that I honestly found exciting.

I tweeted the clip, jokingly commenting that I’d “won Metal Gear Solid V by creating this beautiful moment,” but it had really felt this way to me. Creating this moment had been as fun and rewarding to me as anything else the game offered. Playing MGSV isn’t just sneaking and shooting, or at least for me it isn’t. This, too, is play. So obviously, I get frustrated with the “Git Gud” players, those who feel that games are at their best when they’re perfectly calibrated tests of raw skill, that the only thing that matters is having an awesome KDR, or earning the highest possible rating on missions, or whatever.

But the truth is that it’s not just hardcore gamers who set limits on our notions of play by talking about games like this. A lot of us do it, even a lot of us who consider ourselves emphatically opposed to the “Git Gud’ brigade. We do it when we look at a game like Fortnite and see it only as one simple thing, a struggle to be the last remaining survivor, without at least acknowledging all the other things a player might go to the game for. We do it when we deny the possibility for moments of strange beauty to emerge from even a grim, ugly, grossly misogynistic game like MGSV. We do it whenever we, ourselves, adopt a limited, conventional understanding of what it means to really play a game, rather than fully engaging with all the different ways that we can find ourselves and each other in the spaces that games create.

-----

I’m currently looking for work. If you enjoy my writing and are in a position to do so, please consider supporting me on ko-fi.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

198X and Being Players in a Dangerous Time

NOTE: This piece describes 198X in detail. I encourage you to play the game yourself. It’s currently available on Steam and PS4, costs $10, and takes about 90 minutes to play.

-----

There’s a song I love by the Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn called “Lovers in a Dangerous Time.” To me, the song is about how the things we might take for granted as a normal part of our lives most of the time can feel frivolous or wasteful in times of great crisis, yet it’s also in those difficult times that we may need those things the most. I mean, how can you go on a romantic getaway when immigrants are being held in nightmarish conditions in concentration camps here in the United States? But on the other hand, isn’t it in these times that we most need to be reminded of our own humanity, the humanity of others, and why a better world is worth fighting for?

When you're lovers in a dangerous time

Sometimes you're made to feel as if your love's a crime

Nothing worth having comes without some kind of fight

Got to kick at the darkness 'til it bleeds daylight

Personally, I often find that many video games, movies, television shows and other types of art that I normally enjoy begin to feel hollow and indulgent when I can’t escape the awareness that moral atrocities are being committed by my own government. However, it’s also true that such times are precisely when art that cuts through the crap and makes me feel something deep and genuine is more vital and necessary than ever.

Twin Peaks: The Return was essential to me during the first year under Trump, not for being the most “woke” thing on TV (it wasn’t) but for being such a strange and uncompromising show that watching it felt like being blasted with a high-pressure water cannon that washed away the cynicism I’d cloaked myself in as a way of enduring the horrors of the week. On one episode, David Lynch’s own character, FBI agent Gordon Cole, tells chief of staff Denise Bryson, a transgender woman, that he told the agency men who didn’t accept her to “fix their hearts or die,” and there was the show itself, each week, working its own magic to fix my heart, to keep me human in dehumanizing times.

youtube

For me, the new video game 198X enters this same category; it’s one of those rare and urgent works that does what we most need art to do when we most need art to do it. In 198X’s launch trailer, we see footage of games from an assortment of genres as the protagonist, Kid, says, “This is not just a beat ‘em up. This is not just a shoot ‘em up. This is not just a racing game. This is not just a ninja game. This is not just an RPG.” This trailer got me fired up for the game because I felt as if I knew exactly what Kid meant. When I was a kid myself, back in the years of 198X, games were much more to me than what they may have appeared to be on the surface. In my desperation to escape from anguish both internal and external--the pain of gender dysphoria, a home racked by alcoholism and instability--I could turn even a simple, tedious game like Capcom’s run-and-gun Commando, one of the few NES cartridges we owned, into a valiant struggle to triumph over the forces that threatened to swallow me whole.

Like me, Kid is an expert at finding deeper meaning in the space between themselves and the game. And it only makes sense, since like me, Kid has a need for escape, and a need for meaning. 198X avoids the use of any gendered pronouns for Kid--the only voice we hear throughout the game is Kid’s own, as they narrate their own story--but I believe Kid might be trans or genderqueer. At least, in the absence of the game asserting otherwise, this is my headcanon. I have to admit, seeing a character like Kid in a game still feels like coming across an oasis in a desert. Such representation is so rare, and so precious to me, that it feels life-giving. Brilliantly delivered by Maya Tuttle, Kid’s narration offers us tremendous insight into who they are, even as they remain a fiercely guarded individual. During one of the game’s many gorgeous pixel art interludes, Kid reminisces about how they used to frequent a nearby video store with their father. “But then, we didn’t go there anymore,” Kid says, hinting at some undefined strife that has driven their family apart. “It was no big deal,” Kid says, revealing just what a huge deal it was.

198X’s narrative offers little in the way of specifics, and to me, this only makes it stronger. It asks us to identify with Kid as a player, to feel the games the way that they do and to understand how those games might take on a meaning that reaches beyond the basement arcade that becomes Kid’s refuge. When you start 198X, you’re immediately thrown into Kid’s experience as a player. The first thing you see is an intro sequence and title screen for Beating Heart, a beat ‘em up released in the year 198X. You hear the sound of a quarter sliding into the machine, and then it begins, you’re playing, controlling a brawler in a red hoodie--Kid’s signature color--clobbering an assortment of punks who are out to stop you for reasons that are never explained. They don’t need to be. Kid feels antagonized by the world. Fighting just to survive. That’s why the act of defeating the people who stand in Kid’s way is meaningful.

198X is a game about how games can mean more to us. If it didn’t let the games that Kid plays within it make their own kind of meaning, unfettered by story specifics, it would undercut its own effectiveness. Unlike so many pixel art games that play as homages to the past and simply want to replicate and capitalize on our memories, 198X is interested in commenting on them, in exploring just what our experiences with the games of the past may have meant to us. Stories in games back then were routinely disposable but that doesn’t mean that the games didn’t mean anything. They did. Through their imagery and music and the way they made us feel, they took on all kinds of meaning, offering places where those of us who felt like losers could be heroes, where those of us who never felt like we fit in here in the real world could belong, could be wanted, could be needed.

Thankfully, 198X prioritizes emotional truth over historical accuracy, allowing the games that you play as Kid to do things that real arcade games of the 1980s never did. After playing Beating Heart for several minutes, making your way out of a subway station and onto a city street, something surprising happens: the camera pans up and away from our hoodied hero to take in an unreachable skyline in the distance. Beating Heart fades out, and it’s only then that we first see Kid, alone in their room in their suburban home, a city in the distance representing all the freedom and possibility that Kid dreams of, but it may as well be a million miles away, for all the good it does them.

Unable to achieve that kind of escape, Kid finds a different kind at the local arcade, telling us, “In front of these machines stood some of the coolest uncool people I had ever seen. They were the freaks, the geeks, the misfits, the outcasts, the real rebels, part of something the outside world could not understand, or even knew existed.” Is that the kind of narration some people might find cheesy? You’re damn right it is, and thank goodness for it. I have no patience right now for irony. Give me something earnest, sincere and openhearted. Kid may be emotionally guarded but 198X wears its heart on its sleeve and I am here for it.

My favorite moment in 198X comes a bit later, after Kid reveals their crush on a girl at their high school. “Oh, man, that girl was born a rebel, free to go wherever she wanted to,” Kid says as we see their crush peel out of the high school parking lot in a black sports car, leaving Kid quite literally in the dust. “Free in a way I could still only dream of,” Kid says, and instantly we’re presented with the title screen of 198X’s driving game, The Runaway, which begins with a black sports car speeding off into the distance, leaving Kid’s car, your car, a red sports car in the foreground, pursuing the driver of the black car and the freedom that she represents.

The Runaway’s most direct reference point is probably Sega’s 1986 racer OutRun (one of the best games of all time, as I talk about in this video), but OutRun offers an escape. In The Runaway, Kid can’t quite get away from reality. You make your way from a barren desert to the outskirts of a city, and Kid begins to speak, completely blurring the already thin lines between their real life and their experiences with the games at the arcade. “Nothing could beat the rush of the highway,” Kid says. “The speeding cars reminding me that there was a way out, a road to somewhere, the city on the horizon. I’d drive all night to get to that place,” Kid says with their characteristic guarded longing, and just then, a soaring, yearning guitar screams above the ambient synth soundscape, sending chills down my spine. So often in the games of the 1980s, music was where emotional complexity could flourish, even when the narrative was just a flimsy excuse for you to run through deathtrap-laden levels and blast killer robots, and 198X’s score is consistently up to the task of capturing the heightened emotion of the period’s best video game music, but what it does here is special, even by those lofty standards.

It’s a piercing, perfectly calibrated moment, but it’s not the last of The Runaway’s surprises. You make it to a bridge, speeding past highway signs that indicate you’re getting closer and closer to the city as Kid talks about how the games at the arcade have changed their life. “Down here, I was free. I was in control. No one told me where to go or what to do. The only bad part about it was having to come back up to the real world.” Just then, you run out of time. Your car slows to a stop. All the other cars speed on, bound for the city, but for you, it remains out of reach. And isn’t that just how it feels sometimes, like there are freedoms that others enjoy, that elude you, no matter what? It is for me, anyway.

The final game you play as Kid in 198X is called Kill Screen. A rudimentary first-person sci-fi RPG of sorts, it has no analog in the actual arcade games of the 1980s, so far as I’m aware, but that doesn’t matter. 198X is an emotional journey, not a historical one. In Kill Screen, you must slay three dragons, all the while taunted by an artificial intelligence known as Motherboard, clearly a stand-in for Kid’s own mother, or at least for the ways in which Kid has come to see their mother as a symbol for all the ways in which they’re trapped. It’s here in Kill Screen that 198X takes its only real missteps. Among Motherboard’s taunts are some statements that feel too plain and standard to evoke the intensity of Kid’s struggle. Sure, when a parent fails to connect with you as a person, even comments like “DO YOUR HOMEWORK” and “DON’T STAY UP” can be painful reminders of the yawning distance between you and them, but in the context of 198X’s economical storytelling, these generic phrases fall flat. Other phrases hit harder, though. When Motherboard’s cold robotic voice intones the words “YOU ARE ERROR,” a Zelda II reference that also pointedly encapsulates how I often felt in the world and how I imagine Kid does as well, I laughed, but it stung a little, too. As I triumphed over the challenges of the dungeon, Motherboard resorted to merely repeating “HELP HELP HELP,” and I felt that Kid’s mom was almost certainly hurting in her own way, unsure of how to connect with her child, the two of them talking past each other, neither sure how to close the gap.

What does Kid’s defeat of Motherboard actually mean? Where does Kid go from here? I don’t know, and I’m glad the game doesn’t try to spell it out. All I know is that there are still possibilities in Kid’s life, just as there are still possibilities in mine, and that games can mean something valuable and real, even when the world feels like it’s falling apart.

I don’t expect 198X to work on everybody the way it worked on me. After all, it’s a game about how deeply personal our experiences with games can be, how games can take on larger meanings in the context of what’s happening in our own lives. We take our life experiences into the games with us--Kid’s ambiguous gender identity, for instance, is hugely meaningful to me, in ways it may not be to others--and we take the meaning we find in the space between ourselves and the games we play back into our lives. 198X doesn’t just understand that; it captures what it is to find the kind of meaning you so desperately need in a game right when when you so desperately need it, and god, do I need it now. This is one of the best games of the year.

-----

Thank you for reading. Please consider supporting me on ko-fi. I could really use the help right now.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fear and the Flow of Stories Untold

The terror of Stories Untold lies in the inexorable. I often respond to contingency in games, chance and difference and the divergent manifestations of player action. It’s part of why I love Fortnite so much, the way so many factors collide to shape my experience in each match, the way player structures all over the map tell the stories of encounters that played out in specific ways.

Stories Untold has none of that. It isn’t just a game without real choice. It’s a game that makes your own participation in the march through the inevitable horrors laid out before you feel like an act of reluctant but necessary confrontation. Its first chapter, The House Abandon, takes the form of a text adventure running on a low-power computer from the 1980s, and as the narrative twisted inward on itself, I wanted to do just about anything but type phrases like “Go upstairs” and “Enter bedroom,” though I knew that there was no other way forward. Sitting there alone in my apartment in the dark of night, it took real psychological effort for me to punch the keys and hit Enter. I had to steel myself.

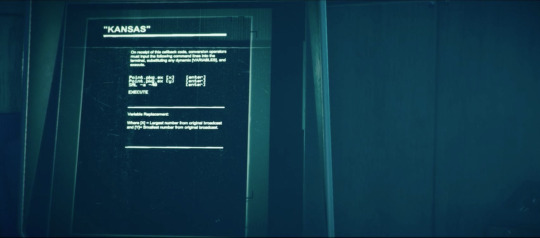

So I was surprised when, after the first episode unnerved me so deeply, I found a strange kind of comfort in the game later on. In the game’s third episode, the aptly named The Station Process, you receive radio signals, and must enter strings of data into a computer terminal by cross-referencing aspects of the signals with a document kept on an old microfilm machine. The data’s there. It’s not hard to find. You just need to go through a process, a very clear and straightforward process of a few steps to find it, and then type it into the computer. And I love it. I love the flow of it.

As a writer, I don’t enter a state of flow very often. I don’t know how it is for other writers, but for me, it’s routinely an agonizing process. The conscious, critical assessment of every word, every sentence, every paragraph I produce. The impostor syndrome. The feeling of failure always nipping at my heels. The agonizing need to settle for imperfection, to accept, to move on, to let go, to let the world see what I’ve produced.

In writing, there is real fear. Fear of never producing anything worthwhile again. Fear of not being able to continue making any kind of living. Fear of what the future holds, or doesn’t. And while I don’t miss the time I spent working in video stores and coffee shops, writing rarely offers me anything like the state I entered when reorganizing movie rentals on the shelves, or washing dishes, or letting my muscle memory carry me through the process of making lattes and mochas and cappuccinos. In that place, I felt safe. Capable.

Perhaps it is strange that one of the pleasures of a horror game would come from the moments in which it made me feel safe and capable, but it’s nevertheless true. I’ve never used a microfilm machine in my life, but it’s really straightforward, once you get a handle on it. I knew, playing that section of Stories Untold, that there was no way I could lose, or get it wrong. I just had to find the information I needed and type it in. Very much like looking up the answers in a hint book, but without any sense of cheating, because this is exactly what the game wanted me to do. Flip to the right page, magnify the pertinent details, type them in. It felt like work and I loved it, because it was work that I knew I could do, almost without thinking about it, and yet so much more involving than investigative processes in games often are.

I hate investigations in games that consist of me doing little more than holding a button to scan some piece of evidence while my character, or my character’s gadgets, come to all the conclusions. Give me something more to do, let me feel more involved. Give me a process in which to partake, even if it’s not challenging, because a simple multi-step process can often be a pleasure unto itself. If a character has a job to do, let me do the job. If it’s work, let me do the work. My life is so scary right now. Give me the pleasure of flow. In the narrow restrictions of a straightforward process, there can paradoxically be a kind of freedom. A freedom from fear. Flow is a good place to be.

---

Watch my playthrough of Stories Untold:

Episode One

Episodes Two and Three

Episode Four

---

Support me on Ko-fi as I look for paying work.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

lonely warriors across space and time

Keleyna of Azeroth

Keleyna awoke in a small tent. Or was this something other than waking? Somehow she knew that it had not been hours or even days since she had stepped into the tent, but ten months. It was as if she had nearly phased out of existence, as if she were part of someone else’s dream and had been all but forgotten. She thought the sudden sensation of reawakening—re-existing—after so long was not unlike plummeting into a pool of icy water.

Dazed and unsteady on her feet, she emerged from the tent to a familiar sight. Yes, this Alliance fort in the Barrens was the last place she remembered, and seemingly nothing had changed. She stumbled over to a smiling, stationary gnome, Mizzy Pistonhammer, who it seemed was still patiently waiting for the eight pieces of siege engine scrap she’d asked Keleyna to collect for her ten months ago. The distant sound of explosions told her that goblin suicide bombers were still steadily charging the battlements. Gods, this world seemed so resistant to change, the constant conflict as pointless as it was endless.

Still, as she left Fort Triumph to go do something, anything, she remembered that she loved the Barrens. A phrase formed in her mind: “Lonely as I am, together we cry.” She didn’t know where it came from—a fragment of a mostly-forgotten song, perhaps—but whatever the source, it seemed fitting. In a world where her actions so often seemed insignificant, there was something oddly comforting about the forthright way in which the Barrens seemed to say to her, Yes, you ARE small, just one little, tiny part of this vast world, this mysterious universe. There was a spiritual comfort in the sparseness of it all, the heat of the dry, cracking earth a balm for her loneliness.

A balm, but not a cure. When she’d last gone to sleep all those months ago she felt a troubling void inside of herself, a persistent lack of purpose or meaning to all of her questing. She couldn’t recall any dreams from the deep sleep into which she’d fallen, but if she’d had any, they clearly hadn’t offered any answers.

Keleyna decided to see if she could be of service to the dwarves at Bael Modan, and when Marley Twinbraid asked her to retrieve his tools from the nearby digsite, she immediately set herself to the task, as much to distract herself from the troubling thoughts and feelings she couldn’t shake as anything else. It wasn’t long until she returned with the tools in hand, which Twinbraid promptly used to repair his flying machine. He entreated Keleyna to join him for a quick flight to his father’s nearby camp, but shortly after liftoff, a massive explosion shook the air around the contraption, and they went plummeting toward the earth.

Walking away from the wreckage unscathed, Keleyna wondered if she shouldn’t be a bit shaken up about what had just happened, but somehow she knew she hadn’t been in any real danger, nothing had been at stake. This was just a bit of fun, an adventure, a chapter in a story that couldn’t really hurt her, no matter what happened. But, then, what was the point? People didn’t usually go to Disneyland alone and ride the rides by themselves, she thought. The magic wasn’t in Pirates of the Caribbean itself; it was in making memories together. It was in holding hands on the ride. It was in going to the Blue Bayou Restaurant with people you loved right afterwards, your spirits buoyed by your shared experience. Wait, what’s Disneyland?

She’d heard rumors that soon, through some sort of arcane magicks, adventurers who so desired would be able to return to the way things had been long ago, before the great cataclysm remade the world. Some said that what had made things better then was that people were friendlier, that they adventured together more, they cooperated more, they talked more. Keleyna definitely felt the absence of these things in her adventures. She’d recently had the eerie experience of venturing through a dungeon with others, nobody saying a word to each other the entire time, and when it was over, they all parted silently, as immaterial to each other as phantoms.

She couldn’t say if things had been better back then. She hadn’t even existed. But she seemed to carry with her the vague memories of a night elf druid who had existed back then, someone who was somehow both her and not her. When she examined the place in herself where those memories resided, she saw some warm recollections of fellowship, but also some frustration and bitterness, as the druid quickly fell behind those she’d called friends, lacked the experience needed to journey alongside them any longer, and found herself feeling lonely and left out.

Keleyna imagined a goblin zeppelin drifting across the sky, blaring a repeating announcement: “A new life awaits you in World of Warcraft Classic! The chance to begin again in a golden age of opportunity and adventure.” She’d heard some big proponents of Classic, as the land through the portals was called, use the slogan “Make Azeroth Great Again,” a phrase she found repellant, though she couldn’t articulate exactly why. Maybe it was just that people who held romanticized notions of the past tended to be hostile to people different from themselves in the present.

She hated the war. She desperately wished that the Alliance and Horde could put aside their differences once and for all, and learn to coexist. She even sometimes felt that the Alliance might well be the more unjust and oppressive of the two, though she couldn’t say that out loud, of course. In her mind, the only real hope was to create a new future that looked like nothing the peoples of Azeroth had ever seen before, not to go back to the earlier years of this relentless conflict. But she was also willing to try just about anything at this point. If there was even a chance that the togetherness she longed for would be waiting on the other side of those portals to the past, then why not make the leap?

The portals hadn’t been opened just yet, though, and while the warm empty vastness of the Barrens had been a welcome comfort, it couldn’t stave off the feelings that sapped her will from within for long. Craving a change of scenery, she hopped a gryphon to Theramore Isle, the sturdy trees and salty sea air a welcome change from the dry heat of the Barrens. She entered the inn and felt a pang in her heart at the sight of its emptiness. Weren’t inns like this supposed to be places where adventurers connected, sharing tales of their latest quests over flagons of mead? With a heavy sigh, she sat down, wondering when she might reawaken, or if this time, she might slip out of the world’s dreams forever.

-----

Many miles away, something flies from the surface of a blue marbled sphere…

-----

The Guardian, Milky Way Galaxy, sometime in the future

She had a name, of course, though nobody knew it but herself. People just called her The Guardian. There were other guardians, of course--tons of them--but if you just said “The Guardian,” everybody knew you were talking about her. After all, she was the one who had done that one big thing, and then, later, she’d done that other big thing, too. She couldn’t actually tell you what those things were that she had done or why exactly they’d mattered so much, but the Vanguard clearly relied on her to take care of the biggest problems that came along. Oh, and she’d avenged Cayde’s death. That, at least, had been an adventure she’d more or less understood, and she’d liked Cayde a lot, but she didn’t feel great about revenge as a motivator. Still, her options had been to do that or to not do anything, so she’d done that, too.

Everyone knew of her, but nobody knew her. When she walked past the ramen shop in the Tower, the people at the counter would talk in hushed whispers, wondering what the Guardian really fought for, and if this woman who had done so much for so many others had anything, anyone, in her own life. Or at least, the Guardian liked to think that this was true. It was her own personal headcanon. The world hadn’t given her what felt like a meaningful story, so she created one herself. She was a legend in her own mind. Sure, she’d fought alongside other guardians a handful of times, guardians she’d known and felt safe with, and those times had been, by far, the most enjoyable and meaningful of her adventures. But those guardians had disappeared without a trace, long, long ago. Now, she knew she could team up with other guardians at random, but she would never do that. She had strong defenses up, and with good reason. Too many bad experiences, too many painful memories.

So she worked alone. It was something to do, but it felt empty. She’d go on missions and get some gear that raised her light level a bit. It was tangible progress, but to what end? So that she could go on more missions and get more gear that raised her light level a bit? Was this all there was?

She looked up at the Traveler, that mysterious being, a fusion of magic and technology that hinted at possibilities beyond this life of guns and blood, and wondered if anything stirred inside of it. She wondered if there actually was more than this, or if this was all there was. She wondered what it was all for, and figured that people had been looking to the sky and wondering this for as long as there had been people, so at least in this, at least in feeling alone and lost and uncertain, she was connected to everyone who had come before. But that was cold comfort as she climbed into her little single-seater starship and set out for The Tangled Shore in hopes of finding a better pair of gauntlets.

-----

“I wake up scared, I wake up strange, and everything around me stays the same.”

--BNL, “What a Good Boy”

-----

Carolyn, Berkeley

Here I am, the link between these two characters, projecting all my own doubt and dissatisfaction onto them.

Things are up in the air right now, Unstructured. Scary. The one constant is that I’m steadfastly working on a long-term project that’s quite unlike anything I’ve done before. It requires a lot more planning. I know where it’s going. I mean, I don’t know exactly what turn it’s going to take at every crossroads, but I have a map to the final destination. There’s comfort in this, but it also means that this writing comes from a different place than so much of the writing I’ve done. I believe in it. I feel good about it. I like doing it and knowing that I’m capable of doing it. But also, it’s safer, less emotionally urgent. (Whether or not it will ever see the light of day, now that is a question of some urgency, as it’s not exactly pulling in any money just yet, but that’s a different matter.) That project aside, lately I’ve felt like I’m looking for a reason to write. The pinprick, the provocation, the punch in the face. The things I usually find in life and in art, and in the space between myself and the games I play.

Destiny 2 and World of Warcraft don’t give me those reasons. So why do I keep returning to them, when whatever comforts they offer are fleeting, when they leave me feeling as empty as when I started? Why, when I’m so desperate for connection, do I keep playing alone these games that are designed to be played together? Why don’t I take the hours that these games swallow up and use them to read a book? Is it because I think that at any moment, something may change? Is it because I know that, while a book may be far more worthwhile, I won’t find the connection I crave in its pages, either?

I want games that fuck me up. The first episode of Stories Untold, man, that fucked me up. My brain buzzed for a few hours afterwards with the excitement and stimulation of having played something truly surprising. Destiny, WoW, these games might be fun if I had people to play them with, but the one thing they will never be, especially not as long as I play them on my own, is surprising. I know exactly what I’m in for each time I fire them up. And yet I do it again and again and again.

Here’s why I think I keep coming back: Because in this moment, when my life feels so uncertain and terrifying, I know for certain that in those worlds I can succeed, that after an hour or two, the numbers that define my character will be a little bit higher than they were when I started. Things feel so out of my control right now. Here’s a place where I can have a kind of control, however small, however empty.

But games can’t be the answer. Life has to be. A few shallow, friendly connections won’t cut it, whether it’s people I hang out with but don’t really know in the real world, or people I run dungeons with in WoW but never really talk to or touch. As Olivia Laing so perceptively writes in The Lonely City, “[L]oneliness is hallmarked by an intense desire to bring the experience to a close; something which cannot be achieved by sheer willpower or by simply getting out more, but only by developing intimate connections.”

Or, as Bruce Springsteen sang,

I'm dying for some action

I'm sick of sitting 'round here trying to write this book

I need a love reaction

Come on now baby gimme just one look

Because that’s where life is. That’s where the reason to write is. That’s where the reason to play is. You take what life gives you and you bring it to those things. But if life isn’t giving you the stuff of life, what, then, do you do?

I don’t want to be a warrior anymore, or at least not a lonely one. I don’t want the Boba Fett mystique. When I was younger I thought maybe I did, but now I know I don’t. Keleyna and the Guardian don’t come from anywhere, they sprang into the world fully formed as adults with no past, no family, no history, but I want someone to know where I come from. They quest alone, or when they do team up with others, it’s a fully superficial affair, no words exchanged, no lasting connection. I want to go on adventures with someone who takes on my complexity and lets me into theirs, someone I can have a real conversation with at the end of a long week, someone to walk around a real city with, someone I want to be there for and who wants to be there for me.

It’s not that I want to stop playing. Not at all. I just want the flame to be reignited. I want something to hold onto, something I can bring back to my time with the controller to make it all mean something. I’m sick of sitting ‘round here trying to write this book.

-----

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, please consider sharing it, or, if you’re in a position to do so, supporting me on Ko-fi. All donations are greatly appreciated as I continue looking for work.

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

In my new video, The Lost Magic, Menace, and Melancholy of Diablo, I consider what made Diablo such a memorable experience for so many players. It’s about a great deal more than just the hack-and-slash lootfest mechanics, though those were undeniably captivating at the time. It’s about how the game uses music and visuals to create a palpable atmosphere of gloom and dread, and also about how the game actually makes you feel vulnerable and fallible, in sharp contrast to, say, Diablo III, which is an unmitigated power fantasy through and through. Thanks so much for watching!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

California Dreamin’

youtube

Here’s my new video, about the incredible style of OutRun, and the power and the limits of the fantasy it offers. OutRun is one of the greatest games of all time, and it’s now available on Switch.

Please subscribe to my channel, and look out later in February for a short video on the tone of Diablo. Thanks for watching!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tower in the Distance

youtube

I think the original Castlevania was a masterpiece of early environmental design. In this video, I discuss some of the reasons why. I have plans to create a video about the classic driving game OutRun next month, too, so if you like this video, consider subscribing to my YouTube channel. Thanks!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tokusatsu, Video Games, and L.E. Hall’s Katamari Damacy Book

I had the pleasure of reading my friend L.E. Hall’s forthcoming book Katamari Damacy, an exploration of the wonderfully original and joyous game of the same name: the circumstances that led to its creation, the distinctive creative philosophies at its core, and, ultimately, what it all means. The book as a whole is a perfect pairing of author with subject matter. Who better to write about the celebration of play for play’s sake that is Katamari Damacy than someone whose work as a designer of puzzles and escape rooms also represents a championing of the need for play in all of our lives?

There’s one particular statement in the book that stuck with me. It comes from an interview with voice actor and Japanese pop culture writer Mike Dent. Dent sheds some light on the significance of Jumboman, a character who appears briefly on the TV being watched by the children of the Hoshino family, the focus of the game’s cutscenes.

The glimpse we get of Jumboman is a nod to the specific assortment of Japanese superhero TV shows collectively referred to as tokusatsu. If you grew up watching Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers, which used footage from the tokusatsu show Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, you probably have an instinctive ability to identify tokusatsu when you see it: the overblown physical expressions of emotion by masked and costumed actors, the charmingly cheap production values. Of the genre, Dent remarks:

...There are tons of these shows where maybe it’s some quick editing and an exploding dummy of a monster to show someone getting killed, but you’re visually provided with enough information to understand what’s happening. And when you’re a kid watching, that’s the kind of stuff that sets your imagination on fire with excitement to fill in the blanks. The fact that it’s today and we still have men in giant robot costumes fighting monsters in miniature cities speaks volumes about how intact this idea is.

Hall then makes the connection between tokusatsu and Katamari Damacy, writing:

In addition to the literal reference to this era of Japanese culture, Katamari Damacy also embraces this philosophy of keeping things simple and exciting as a method of stimulating the imagination. By referencing nostalgia, it allows the player to revisit happy childhood memories as they engage in a childlike form of play.

I didn’t grow up with tokusatsu myself--I’m just a smidge too old to have been in the target audience for Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers, and the only Japanese media I was exposed to as a youth was anime. I did, however, grow up with the Atari 2600, and this observation about tokusatsu stimulating the imagination rings true for my experience with those games as well. In my mind, the yellow square of Adventure...

became myself, a brave hero in a fantasy world who ventured into ominous, towering castles, slaying dragons and recovering the Magic Chalice.

In Asteroids, I felt dwarfed by the vastness and darkness of space, alone, fighting for survival with everything I had.

These adventures and many more continued in my imagination long after I stopped playing, my mind visualizing the interior of my doomed little ship, or the treasure-filled chamber where the Magic Chalice was kept. That was a huge part of the fun; it was, in fact, part of the whole experience of play the games offered. Now, games so often want to offer up every detail, creating a kind of immediate immersion at the expense of asking anything of your imagination. Something gained, I suppose, but also something lost.

Given the sheer number of objects in Katamari Damacy’s levels, and the limits of the PlayStation 2, of course the game had to rely on a simplified visual style. But a game of such whimsy and silliness is at odds with realism anyway. How great is it that Katamari Damacy, a game that served as a kind of rebuke to the grim shooters and crime epics dominating the market at the time, enthusiastically asked your imagination to meet it halfway, while so many other games were striving to fill in all the blanks for you?

(L.E. Hall’s book Katamari Damacy comes out on October 16th. You can preorder it here.)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Favorite Non-Places I: Where I Once Played Hacky Sack in Sight of the Golden Gate

California Games hit the Commodore 64 in ‘87, but it was probably a few years before it made its way to me, and it would be many years more before I looked on the Golden Gate Bridge with my own eyes. Epyx’s smash hit included an assortment of summery California pastimes, like surfing, roller-skating along the beach, and doing stunts on a half-pipe with the HOLLYWOOD sign in the background. But it was the zen tranquility of hacky sack that made the game a refuge to me. (The game calls the sport “footbag,” but it’s always been hacky sack to me.)

At first, I fumbled and failed every time, and the experience was anything but tranquil. In time, though, and with practice, I learned to keep the hacky sack in the air, seamlessly transitioning from one trick to another to another, racking up scores that topped the charts. It was a kind of flow that made me feel so much more present on that mythic stretch of green than I ever did in my actual day-to-day life.

I guess the closest thing to this place is Crissy Field, but I don’t think a spot like this actually exists, a spot from which you can see both Alcatraz and the Gate like that. And even if such a spot does exist, it’s still not this place. Not really. Because every time I go here, it’s always exactly the same. There’s that little sailboat out on the water, a tiny detail that makes my heart ache as I wonder who’s out there, what cares they’re forgetting in each other’s company, and don’t they wish it could last forever? It can, but only here, in this place that isn’t real to begin with.

California Games was ported to every conceivable platform at the time but most of them got it wrong. Here it is on the NES, the iconic Golden Gate nonsensically replaced with a bridge of featureless gray, the hills of Marin looking more like the Rocky Mountains, the whole scene feeling cold.

The Genesis version went too far in the other direction, approaching photorealism in its desire to be faithful to the game’s California setting and losing the original’s potential to become the California of our dreams.

Speaking of California dreams, the other day I heard “Boys of Summer” by Don Henley playing at a restaurant and it took me back, as it always does. I remembered walking along the beach in Santa Monica with the first woman I ever loved. I remembered her playfully yelling “SHOCK!” and jumping over the water as it rolled in, mimicking a moment from a live performance of “Shock the Monkey” by Peter Gabriel, then and still one of my favorite singers. She was a brilliant and extraordinary young Muslim woman from Pakistan, and I was her blue-eyed, blonde-haired all-American “boyfriend.” We hid our relationship from her disapproving parents and I hid the truth of myself from her. There was so much shame inside me then. In some ways, there still is. For all that’s changed, I still remain awkward, out of sorts, a misfit, unable to inhabit my body or the present moment the way so many people around me seem to do so effortlessly all the time. All of that can fall away though, sometimes, when it’s just me, and the controller, and this instant, the need to be there, the need to react, and nothing more.

I realized, hearing that song at that restaurant the other day, that there’s no going back to that beach. That beach now simultaneously does and does not exist. I can return to Santa Monica and remember being there with her, but the beach I visited with her was the beach it was then because it was then, because I was with her. The song knows this. “Those days are gone forever, I should just let ‘em go but...”

But from my Southern California home back then, I could travel to a Bay Area that doesn’t really exist, but that, unlike that beach at Santa Monica, will always semi-exist, exactly the same as it was all those years ago. The same sailboat is still there making its leisurely turns out in the bay, the same seagull is still flying overhead. And still when I look at that place, I can remember standing there, listening to the waves, feeling the wind in my hair, and being so completely in the moment, so responsive and alive, so damn good at something, that for a little while, there was no shame.

(My Favorite Non-Places is a series of indeterminate length and frequency on some of my favorite spaces and locations in games.)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

new game plus

You know how stand-up comics often have to tour in smaller clubs for months, trying new material, sometimes failing, maybe even bombing, as they figure out what works and what doesn’t, what to sharpen and what to toss out, before having a strong enough set of material for the big live shows and the Netflix specials? And then, after they’ve done the big shows, after they’ve recorded the Netflix specials, they have to start the whole process over again, playing clubs in Poughkeepsie, experimenting and taking risks and facing the possibility of failure as they try once again to build up a whole new set of material?

What with my job and everything, it’s been a while since I’ve consistently made the time to do my own writing about games--the kind of idiosyncratic, personal responses to games that I’d post here in the past. I miss it. I also feel deeply insecure about trying to get back to it. Do I even still have anything of value to say about games? The truth is, I don’t know, man. But I have to find out.