Text

20% There

Yes! I have completed my first year of vet and am now officially 20% of the way there. I enjoyed this semester even though it was quite light on animal handling. I found our dissection labs to be very interesting and absolutely loved learning basic suture techniques (can’t wait to learn more surgery skills).

During this break I am undertaking 4 industry placements (7 weeks). I’ve already completed 2 of them. I spent the week following exams at a barramundi farm learning all about the aquaculture industry. It was hard work (we spent one whole day vaccinating 25,000 fish) but very interesting. The week after that I did 2 weeks at a nearby wildlife sanctuary where I spent my days interacting with, and learning how to care for, a range of Australian animals such as dingoes, squirrel gliders, macropods, wombats, koalas, echidnas, crocs, and a variety of reptiles and birds (including cassowaries!). I was working pretty hard the whole time but I did manage to get a few photos on my last day.

King the dingo:

Oreo the squirrel glider:

Ash the red-tailed black cockatoo (we became best friends after I saved him from the rain):

After Christmas I will be doing 2 more placements. One will be at a dairy for 2 weeks. I’m looking forward to this as the owner of the property seems really keen to have me, even though he’s never taken a vet student before, and happy to let me get in and try my hand at a few different things like preg testing and calf pulling if the opportunity arises.

The other placement is one that I am incredibly excited about. I am going to be working with one of my favourite species, these guys:

In 2 weeks I am flying off to Africa to work with African Wild Dogs for a month! I managed to snag this opportunity by talking to one of my lecturers about his research and simply asking if he’d be willing to take me on for a few weeks as a placement. I could hardly believe it when he said yes. I have never been good at networking before so this is huge for me. Moral of the story: Don’t be afraid to put yourself out there and ask for these kinds of opportunities. The worst they can do is say no. I’ll let you know how it goes!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vet school: A place where you will feel inadequate and behind 90% of the time, and where the other 10% of the time you’re probably in denial.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gastric Dilation-Volvulus Syndrome (GDVs) in Dogs

GDVs is a gastrointestinal syndrome wherein the stomach is seen to flip (usually 180-360° clockwise) on its axis, causing internal damage through ischaemia, inflammation and possibly infection. It comprises three parts:

acute gastric dilation,

acute gastric dilation-volvulus (GDV) and

chronic gastric volvulus.

GDVs is most commonly seen in large or giant dogs with deep chests (Great Danes, GSDs, Irish setters and standard poodles are over represented in GDV studies). A high thoracic depth to width ratio is commonly noted in affected dogs. Other risk factors include:

diet,

gastric volume and position - yep, stomachs vary between dogs,

gastric ligament laxity - what’s holding the stomach in place?

control of eructation (burping) and pyloric canal function - or anything else that will result in gas build-up.

The onset of symptoms is usually acute and can occur after a large meal or a bout of exercise (swallowing air is thought to contribute to the flip). Symptoms aren’t the most specific but the dog’s signalment should certainly ensure that GDV is on your DDx (differential diagnoses list). Symptoms can include:

agitation, restlessness, lethargy;

progressive abdominal distention (tympany) - this will lead to increasing pain as the internal pressure builds/ischaemia begins;

retching, unproductive vomiting;

cardiovascular (CV) compromise - hypovolaemic shock, etc.

Local effects of GDV mainly affect the stomach and spleen - this is due to a compromise in blood supply to both organs. As the stomach and spleen are connected by the gastrosplenic ligament, when the stomach moves it tends to bring the spleen with it. This movement of the spleen can result in avulsion of small gastric branches of the splenic artery and therefore, may lead to ischaemia or necrosis of the stomach (especially the fundic region). Similarly, as tension increases within the stomach, compression of intramural vessels may occur.

Systemic effects of GCV are mainly due to CV compromise (i.e. the mechanical obstruction of blood flow through the caudal vena cava and hepatic portal vein). Any vascular obstruction will result in decreased venous return to the heart, a subsequent decrease in cardiac output and hence hypovolaemia. For this reason, the GDV dog must be managed with fluid therapy in order to return the circulating levels to normal.

Fluids are the main immediate management of the GDV dog but analgesia should ideally be offered as soon as the dog is stable(ish). Pure opioids (morphine or methadone) are good to relieve pain but also calm an animal for exam. Short-term analgesia (e.g. fentanyl) is useful in some cases. If the resources are available, and echocardiogram (ECG) should be performed in order to monitor CV system. Many dogs with GDV will develop arrhythmias - treatment for this should be withheld until all other CV symptoms are stabilised as sometimes GDV-related arrhythmias will resolve themselves. Unfortunately however, approximately 40-50% of dogs who present with GDV will develop a permanent arrhythmia. These are usually ventricular and are caused by myocardial injury.

Once the dog is stable, actually resolving the GDV becomes priority. The first stage in this process is to try and decompress the stomach. Using an orogastric tube is the preferred way to do this but if a tube cannot be passed, percutaneous gastrocentesis can be performed using a large gauge needle. It’s important to measure an orogastric tube prior to beginning the procedure: the tube should extend from the nostril to the last rib. This is necessary to ensure that iatrogenic damage isn’t caused by a too-long tube. The aim of decompression is to release some of the pressure in an effort to prevent further ischaemia.

Regardless of the success of compression, surgery is indicated for every GDV patient. If a GDV dog isn’t operated on, they will almost certainly die (either due to complications or further GDV episodes). The aims of surgery are to fully decompress and reposition the stomach, assess the viability of any affected organs, remove any devitalised tissue and perform a gastropexy (fixing the stomach to the abdominal wall or diaphragm to prevent another GDV in the future). Some things to note regarding GDV surgery:

A distended stomach will be noticeable from size and can be further seen to be a GDV if it is covered by an omental leaf (this is due to the stomach entering the omental bursa during flipping).

Additional decompression can be accomplished by an intraoperative gastrocentesis or with a guided orogastric tube.

Gastric necrosis is reported in ~10-40% of GDV dogs. The stomach should be checked thoroughly for ischaemia and necrosis and if any is present, a gastrectomy should be performed to remove those foci.

It’s advised to wait ~10 mins after repositioning the stomach as bruising caused by the torsion can often be incorrectly identified as necrosis.

The most common site for necrosis is along the greater curvature at the junction between the fundus and the gastric body.

A gastric resection is always a possibility in the case that the stomach isn’t completely viable. If there is too much necrosis then euthanasia may be advised.

The spleen should also be thoroughly checked for damage, especially the splenic vessels.

A gastropexy should always be performed. A gastropexy aims to fix the most mobile part of the stomach (pylorus) to the right abdominal wall.

Post-operative care is important after all surgery. The temperature, respiration and cardiac capacities are very important indicators of any problems. Fluid therapy should be continued and post-operative analgesia is essential (NSAIDs should be avoided). If there were no major complications, the dog can be offered food and water the day after surgery. It’s advised that the patient is admitted for a further 3-5 days for monitoring. In addition to the persistent cardiac arrhythmias mentioned earlier, other complications include aspiration pneumonia, abnormal gastric motility, necrosis or perforation. When treated successfully, there is a good to excellent prognosis for GDV dogs.

If you have any questions, additions or corrections, please let me know! This is my first real vetty post so all feedback is appreciated. :)

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common Ailments in Guinea Pigs

I attended a BSAVA Clinical Club Pub talk on guinea pigs by Jill Pearson, a veterinary surgeon with lots of exotics knowledge.

So what are the common diseases of guinea pigs?

Hypovitaminosis C (Scurvy)

Consequences: parasitic infestation, respiratory disease, pododermatitis, malocclusion, immunosuppression, swollen and painful joints, poor wound healing

Treatment: 100 mg/day vitamin C supplement

In young animals, musculoskeletal damage can’t be reversed – euthanasia

Prevention: use a guinea pig diet with 800 mg/kg vitamin C

Respiratory disease

Bordatella bronchiseptica

Clinical signs: snuffles, severe depression, respiratory disease

Treatment: antibiotics, fluids, nutritional support, NSAIDs

Streptococcal pneumonia

Syringe feeding

Prevention: use a thick mixture and don’t do if guinea pig won’t swallow

Cervical lymphadenitis (abscesses in lymph nodes)

Cause: Streptococcus zooepidemicus

Treatment: systemic antibiotics, possibly excision of node/lancing and drainage of abscesses

Urinary problems

Cystic ovaries

Clinical signs: bilateral flank alopecia, vulval bleeding, palpable lumps in abdomen

Treatment: spaying

Cystitis or cystic/urethral calculi

Usually calcium oxalate calculi

Clinical signs: squeaking while peeing, blood in urine, urine scald

Treatment: use pre-boiled water to drink, add Ribena to water to increase fluids, antibiotics, diazepam (if male)

Weight loss

Dental malocclusion – linked to Hypovitaminosis C

Treatment: dentistry, adjust diet

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis – rare

Clinical signs: weight loss, diarrhoea

Diagnosis: euthanasia and post-mortem

Coccidiosis (Eimeria caviae) – rare

Causes: poor husbandry and overcrowding

Treatment: sulphamezathine/sulphadimidine in water with Ribena (because bad-tasting)

Tumours (lymphomas), pododermatitis, painful temporomandibular joint

Pruritus

Trixacarus caviae – most common

Clinical signs: crusting, hair loss, pruritus, pain, seizures, bronchospasm

Treatment: topical or parenteral ivermectin, NSAIDs vs pain, diazepam vs seizures, bathing to clean skin

Trichophyton mentagrophytes – less common

Clinical signs: starts at head

Diagnosis: microscopic examination, culture

Treatment: topical enilconazole

Pediculosis (Gyropus ovalis, Gliricola porcelli)

Treatment: ivermectin 3x every 7-10 days

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sitting here practising suture technique for my exam and I finally feel like an actual vet student. Thanks brain, only took you a year.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Identify the reptile prolapse

Oh, the kinds of games vet students play :)

Can anyone tell me which body part has prolapsed in each of these pictures?

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I think I’m approaching this studying thing well

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hug Your Cat

As a veterinarian, the medical knowledge I posses can be a great thing. It can also make me a hypochondriac when it comes to my pets, and some conditions I outright dread. One such condition is aortic thromboemboli of the cat, and I had the horror of dealing with another such case this weekend.

For those less medically inclined, an aortic thromboembolism is a blood clot in the aorta. It originates in the heart and shoots off down the aorta to lodge wherever it’s going to go. It could go to the brain, sometimes it goes to a front leg, but most of the time it lodges in the caudal aorta where the massive artery splits into a ‘Y’ intersection to travel down each hind leg. This sudden narrowing of the vessel is where most clots lodge, and is often called a saddle thrombus.

This is hugely catastrophic for the cat. One moment they are ‘normal’ and the next they suddenly lose all blood supply to both their legs. They are unable to move their hind legs and obviously distressed by this. They are painful and paralysed. They often have no rectal tone and frequently defecate on themselves, unaware and unable to drag themselves away. They also have low rectal temperatures, no femoral pulses and if you cut a nail on a hind leg, they usually have no blood flow at all. Basically, the back half of the cat looks clinically dead.

While the front half is aware, and otherwise looks fine.

It’s a cruel condition, and I had to deal with such a patient this week.

(Contains medical descriptions)

Keep reading

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yesterday I had a shift at my university’s pet emergency department. It was incredibly motivating and just what I needed right before exams!

Pictured above are my essentials for what I keep on me whilst doing shifts at the vet school as well as seeing practice:

- Stethoscope for doing the obvious

- Thermometer for doing the even more obvious

- A calculator for those moments where you can’t do basic mental math when a clinician is standing right in front of you

- Reflex hammer for wacking those patella tendons

- Haemostats for getting off super jammed on injection ports off catheters, etc you’ll be surprised as to how useful they are.

- Scissors for cutting the things.

- Pens, as in multiple, because you will lose/have them stolen by clinicians, students, nurses.

- Pen light for doing your neuro exam thang (and when you need a handy light source)

- Note pad for making notes about cases, writing patient weights, drug dosages, vitals etc so you can regurg them back to the clinicians upon request

- Gerado Poli’s - The Mini Vet Guide in Companion Animal Medicine because IT IS A LIFE SAVER.

P.S. it is also my last week of lectures EVER this week. Next year involves being a baby vet on final year rotations!

230 notes

·

View notes

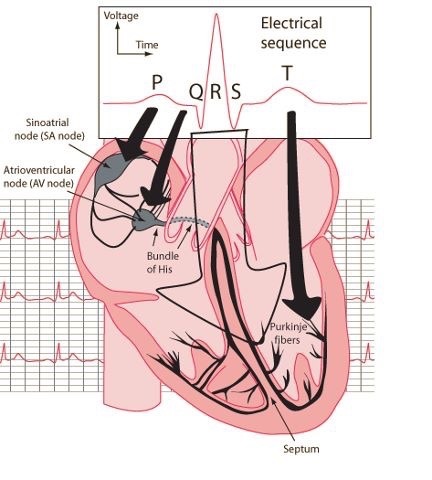

Photo

Electrical sequence of the heart for the visual learner

636 notes

·

View notes

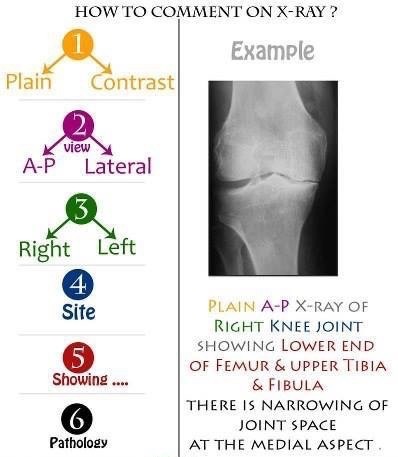

Photo

Confused about reading and commenting on X-rays

Relax and follow the steps

2K notes

·

View notes

Video

Locating the thyroid gland medial and dorsal to the sternothyroideus muscle and getting it to “drop down.” Slide your hand ventral to the sternothyroideus muscle and push your fingers dorsally until they slide over a rounded structure; wrap your fingers over the top and pull it gently towards you. In the horse, the thyroid gland is shaped like a barbell, with two lobes, each lateral to the first few tracheal rings and connected by an isthmus along the ventral aspect of the esophagus.

306 notes

·

View notes

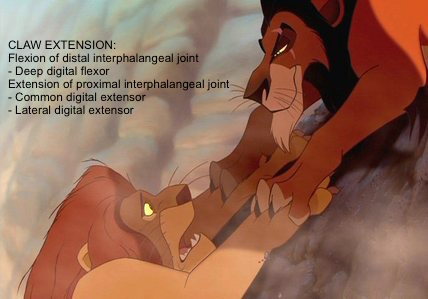

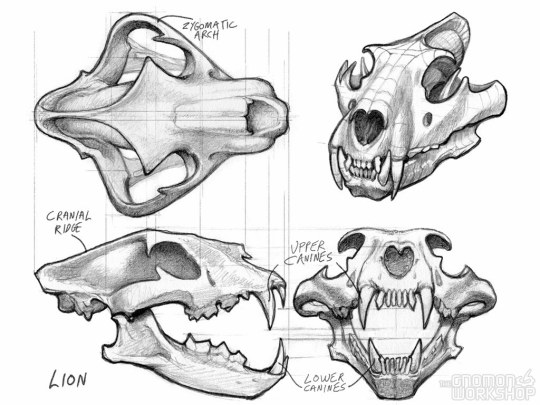

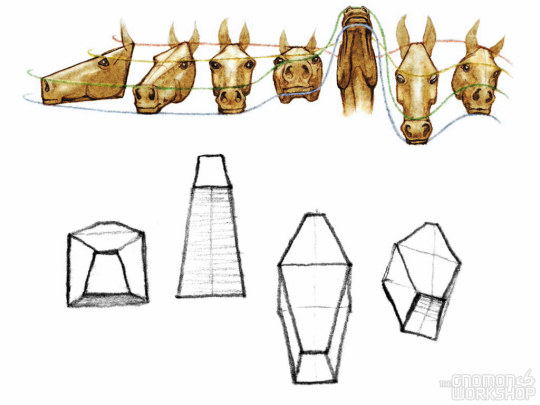

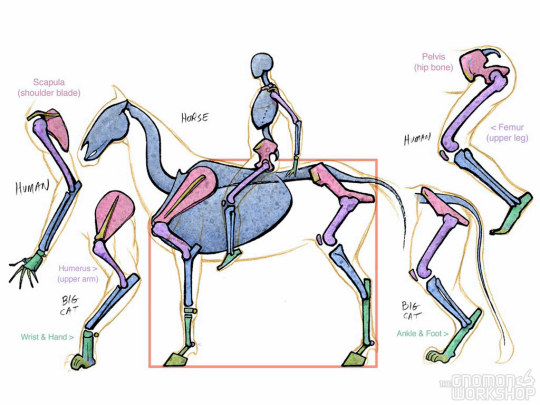

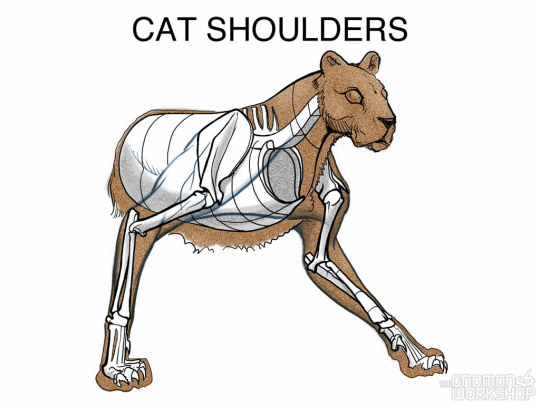

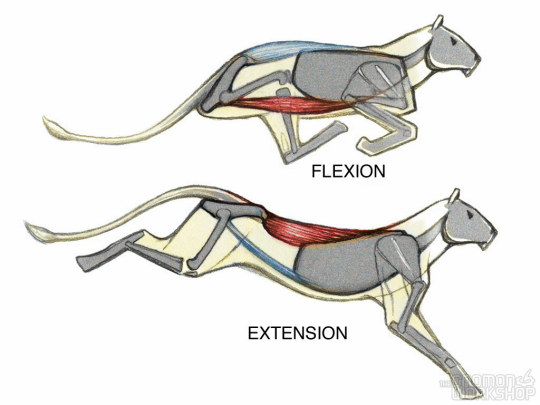

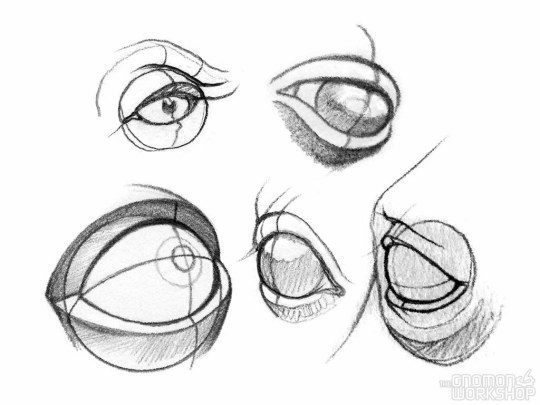

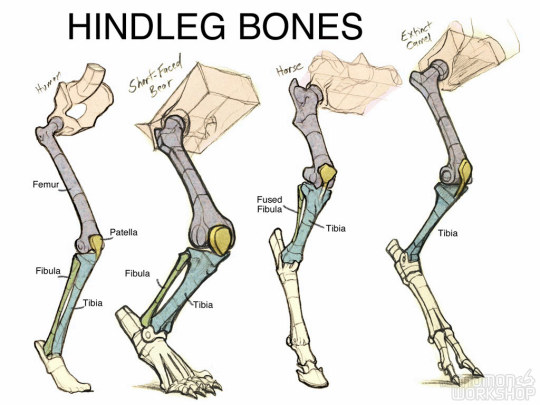

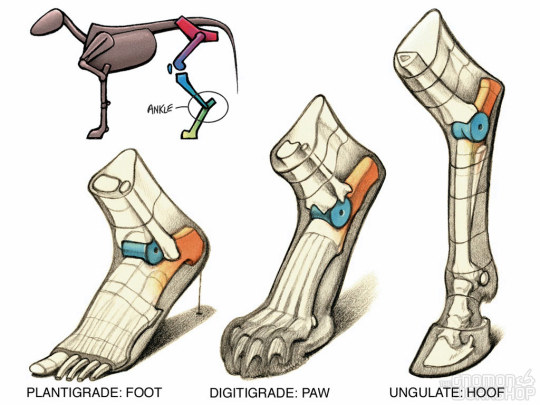

Photo

Intro to Animal Anatomy by Marshall Vandruff

1K notes

·

View notes