Text

Reflection 10: Fuga Modus

(Task 3.2)

I came across Joyce Camilleri’s pandemic-encouraged series quite by chance; currently they are a body of work exhibited at the relatively little Jo Borg Gallery in Sliema, which I randomly happened across while walking home in the evening along Manuel Dimech. Finding the works to my liking, some research told me that the series has travelled around various exhibitory avenues, including MUZA and Il-Kamra ta' Fuq, and with some luck ended up in my own very area. The series themselves were created with a veritable multitude of media; oils, inks, and graphite on canson, acid-free paper, archival boards, or hot-pressed paper. They were created consecutively after one another during the onslaught of lockdowns and quarantine measures at the beginning of 2020, as a result of the termination of live-drawing classes that Camilleri habitually attended. Normally a figurative-oriented artist, Camilleri regularly practiced figure drawing and portaiture during these lessons. When it was announced that they were to be discontinued, Camilleri set about in a new direction, propelled by a vastly changing charged atmosphere of tension and uncertainty.

Owing to the fact that Camilleri lives in Luqa in close proximity to the national airport, two factors relevant to this were responsible for conceiving the series. First, Camilleri noticed the lack of revving engine noise that she was accustomed to hearing – a change she in part appreciated – and instead was confronted with a newfound silence that just kept on lasting (Camilleri, 2021). Secondly, the clear space and fields around Luqa presented Camilleri with a newfound subject matter to draw inspiration from. The natural shape language of the familiar Maltese landscapes readily available to her began to take precedence as a point of inspiration in her work. Thus, sitting at her drawing table, she “switched [her] mind on flight mode” (Camilleri, 2021) and began to work.

A prolific user of the printing press, Camilleri’s oeuvre is rich in aesthetic derived from and composed of print. Monoprints, especially, form a large part of the artist’s process, often creating the print first as a collection of vague, outlines forms and contours, and setting about filling the spaces with a range of simultaneously wet and dry media. The variety of techniques applied to paper are perhaps not evident from photographs, but very much so in real life. Plentiful amounts of grain and noise inform every inch of the achromatic fields and sections, lending the paintings a pleasant matt texture, which prevents the spaces from acquiring a glossy and plastic-like consistency. I feel this is significant, as it creates a certain feeling of void or absence; an empty negative space full of millions of particles, rather than a smooth and gleaming ruber-iness.

The works take a change of direction over time. Placed on the walls according to size and visual theme, the smaller works begin as vertically-oriented and sectioned into large, sharp value shapes selected from the low-key range. They then exponentially increase in scale, and lines begin to faze out through the rendering and blending of forms; the depictions acquire a more palpable sense of volume and resemble turbulent landscapes, seascapes, and horizon lines. All throughout, they keep their texture, value, tone, and adherence to flowing in a singular direction.

The works can be analysed endlessly. Camilleri exemplifies her talents in composing with value, and mastery over the simple basics in order to evoke an essence of timelessness and absence.

0 notes

Text

Reflection 9: Picasso's Minotaurmachy and the Jungian Approach

This seminal etching by a younger Picasso is a study in personal iconographic appropriation; it is often agreed upon by scholars that this print-series much informed the artist’s later ‘Guernica’, as well as other war-centred works, most notably in terms of symbolic and metaphoric imagery that he is well-known for. In regard to Picasso’s personal and/or biographical influences on this work, there is much speculation. It is generally agreed that the work was created during a turbulent and unstable period of his life (Moma, 2024), which was much informed by concerns relating to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, as well as the recent reveal of his mistress’s pregnancy (Marie-Thérèse Walter), causing even further divide and turmoil in his marriage to Olga Khokhlova. The work is a quintessential exemplar of the artist’s surrealist phase, doing much to break logical consistency and the laws of perspective, regardless of the mythological (and hints of religious) subject matter.

A busy scene acted out by a colourful cast of characters unfolds in a frenzy of sketchy, yet organized hatching. It is through this cast of characters by which the Jungain perspective may aid in analysing the work’s ambivalent meaning. Six or so figures (some blend into a jumble of limbs) of alternating age and gender are composed evenly across the page, presenting varying degrees of reminiscence to the company of archetypes that Jung suggested. It is important to note that the archetypes themselves are described by Jung as inherited, collective and - to some extent - culturally dependent inner psychic models or ideals (Kralingen, 2017). Thus, given the highly subjective nature of both the theory and the proposition (that every archetype is subject to each person’s inner psychology), it is inevitable that a highly interpretive approach is unavoidable.

For instance, what can be interpreted as the archetypal ‘mother’ makes her appearance in something resembling the Virgin with Mary Magdalene, who are typically pictured together in religious iconography, owing to their particular closeness within the holy family. This can be seen through the white dove perched at the fore, the primary figure’s veil, and the secondary figures lack thereof – a common way of representing both holy figures in partnership – and the rather elevated position of both, leaving them at the top of a triangular, hierarchical composition. Though Picasso was an avowed atheist, he made regular use of spiritual and traditional religious imagery, similar to Francis Bacon’s abundant use of the crucifixion. Picasso was especially wont to do this in relation to war-related thematic concerns, positioning the role of religion as an actor in the scenery.

Moreover, a minotaur of Ancient Greek mythology hulks over a large area of the work; this can be interpreted as the father, or the anima; an inner expression of masculinity in both sexes, according to Jung. This also coincides with the common usage of the bull as a symbol for masculinity, fecundity, and authority, especially in regard to Spain and its national associations with the imagery.

Other archetypes can be matched with the figures; the disembowled horse may well be the shadow, representing a turbulent and violent subconscious or repressed desire; the animus within the young girl, the female counterpart of the anima, which holds a beaming candle and seemingly threatens the minotaur; or perhaps the wise old man, observable on the immediate left trying to climb out of the painting may represent the departure of reason – a visual metaphor for taking leave of one’s wits. In any case, the work can be interpreted as an interesting, charged, and tense inner map of the psychological state of the artist, who would possibly also have been encouraged by the wave of popularism psycho-analysis attained in the early to mid-twentieth century.

Adams, L. (2020). Art and Psychoanalysis. [online] obo. Available at: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199920105/obo-9780199920105-0030.xml.

Kralingen, A. van (2017). COMPLEX, ARCHETYPE, SYMBOL in the Psychology of C.G. Jung by Jolande Jacobi. [online] Appliedjung. Available at: https://appliedjung.com/complex-archetype-symbol/.

MoMA (n.d.). Pablo Picasso. Minotauromachy (La Minotauromachie). 1935 | MoMA. [online] The Museum of Modern Art. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/60110.

Museu Picasso (n.d.). Minotauromachy | Picasso museum Barcelona | Official website. [online] museupicassobcn.cat. Available at: https://museupicassobcn.cat/en/collection/artwork/minotauromachy [Accessed 22 Jan. 2024].

Princeton University (n.d.). La Minotauromachie (Minotauromachy) (x1986-104). [online] artmuseum.princeton.edu. Available at: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/16133 [Accessed 16 Jan. 2024].

0 notes

Text

Reflection 8: Thoughts on Biographical Analysis

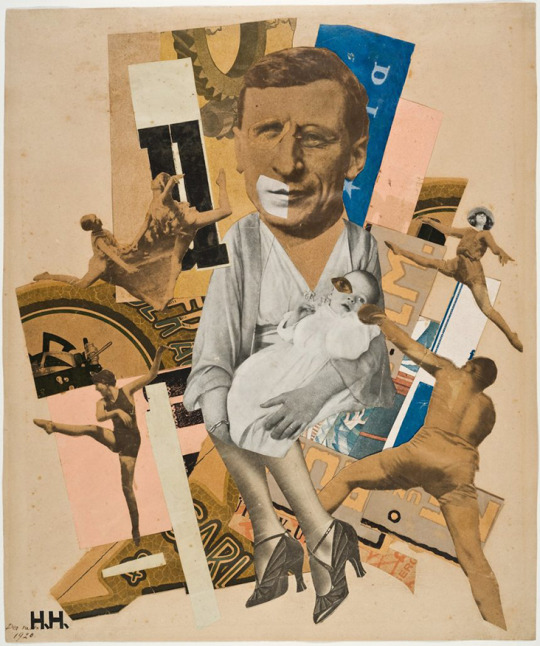

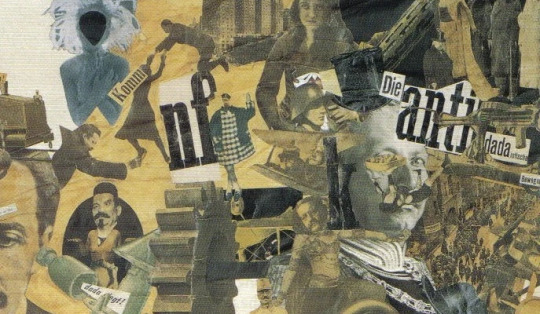

Case Study: Hannah Höch.

At the risk of spouting banal truisms, it is apparent to anyone familiar with the artworld that an artist’s work is almost always inseparable from their personal lives. Socially-oriented anxieties, marital trouble, thanatophobia, personal relationships with class or race, spirituality – a compound of personal tragedies and triumphs can and regularly do inform almost every artist’s works. However, it is with some amount of rarity that one can boast about creating seminal, impactful, and influential work, whose aesthetic and style was unmistakably informed by an arresting personal biography, personality, and individualism; but such is the case for Hannah Höch.

German Dadaist active during the Weimar period – already impressive – Höch was the originator of photomontage, and is largely to thank for the very specific Dada aesthetic taking its place in the art-history timeline. Höch’s work was made to the tune of first-wave feminism that was making its debut around Western Europe and North America in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, addressing the concept of ‘New Woman’, a late 19th century feminist ideal that largely described an independent, energetic and role-resistant woman. Höch famously styled herself androgynously, in part due to a leftover New Woman notion that one must also make changes in one’s apparel to complete a full-bodied resistance to gender role conformism, an act of self-style that was popular in bohemian underground German culture at the time. In tandem, the figures in her works are similarly androgynous, as conscious interpretation of shifting gender roles.

In 1917, having joined the Dadaists, Höch found herself as the only female member of the group; and became known for her independent spirit, self-sufficiency, and sexual emancipation. Her bisexuality informed much of her approach to figurative depiction; along with the other Dadaists, collaborative works between her and other members consistently made campy works permeated with satirical and ironic jabs at the sociopolitical state of Germany, to the backdrop of a gradual descent into a more and more suffocatingly worrisome direction. Notwithstanding, it is significant to note that Höch worked as a Red Cross nurse all through the Great War; owing to the fact that the Dadaists emerged as a response to the devastation of the First World War, it was inevitable that the artist would take a liking to the potent anti-establishment and socialist stances that the Dadaists took, as well as their eagerness to challenge established norms in society and art, which they felt were actively regressing society and explained the devastation and suffering that had come from the recent cataclysmic war. Even to this extent, Höch faced exclusion from her male Dadaist peers:

Most of our male colleagues continued for a long while to look upon us as charming and gifted amateurs, denying us implicitly any real professional status.

Höch’s marginalization as an unconventionally presenting woman led her work to develop into a response to these societal constraints; her collages often feature fragmentary imagery of the female form, challenging traditional notions of femininity and propounding a more multi-faceted and liberated view of women. Her own unconventional experience and presentation of gender are reflected in her own works' unconventional presentation of gender. In true Dada fashion, her bold collisions and collations of popular imagery reflect the critical and rebellious spirit of the interwar years. Indeed, after the takeover of the National Socialists, Höch was one of the artists whose work was labeled degenerate, and removed from public view, as her works and unconventionally gendered figures were considered offensive.

References

National Museum of Women in the Arts (n.d.). Hannah Höch | Artist Profile. [online] NMWA. Available at: https://nmwa.org/art/artists/hannah-hoch/.

MoMa (2014). Hannah Höch. [online] The Museum of Modern Art. Available at: https://www.moma.org/artists/2675.

Blumberg, N. (2018). Hannah Höch | German artist. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hannah-Hoch.

0 notes

Text

Reflection 6: Thoughts on Contextual Analysis

Of all the art theories and criticism methods available to us, contextual analysis seems to be imperishably significant; without it, the history of art is merely a flat continuum of inexplicably variating imagery. In the advancement of thousands of years, biographical details of specific artists may become lost on us; feminist theory, already not employed in every corner of the world as of this moment, may not remain as popular as it in the West this century as opposed to the next; the psychoanalytic approach, already unpopular due to Freud’s long line of dissidents, may be overturned by some new psychological framework that is based on a more advanced understanding of psychology, perhaps achieved via the improvement of the neurological sciences. The assessment, however, of an artwork within the context of its historical and cultural setting, seems to be impossible to ignore if one is to set about accomplishing a holistic analysis of a given artwork, due to the simple reason that the artworks themselves do not occur in vacuum, and are informed - whether the artist likes it or not - by the time they were made in.

To all intents and purposes, contextual analysis itself seems to incorporate by necessity some amount of formal analysis; in fact its goal, it appears, is often to precisely point out the differences in form and quality according to variating time periods. However, there is also the suspicion that, even in the most strictly formal analyses, there is necessarily some amount of context that the assessor is operating under or subject to. Therefore, an interesting interdependency can be observed of the two theories; one cannot formally critique a work without some amount of context, just as it is equally impossible to contextually critique a work without making some amount of reference to the formal qualities. Oxford (Oxford Reference, 2024) states:

Formal analysis can only be a partial analysis, since it backgrounds content, context, and audience factors, and as such it may form part of a larger analytical project. Purely formalist approaches may seek to be objective, but they can also be criticized as privileging the elite interpreter…

For example, if two critics were to be sat in a room, and were presented with an Ancient Greek krater from the Orientalising period (and told only this much), and one is informed he can only strictly use contextual analysis to assess it, and the other is told that he can only use formal analysis — it seems to me the two would inevitably, immediately fail. The former will begin with speaking to the significance of the introduction of the dark-on-pale lily/palmette motif as an influence from increased trade with the Levant, which would undoubtedly mean that, in combination with its still-strongly geometric usage of forms, would place it around the 750 to 580 BCE period — oops, pump the brakes; isn’t that a description of something on the basis of almost purely formal terms? Every inference made came from observable physical properties – one is analysing formally, just as much as contextually. The other, with perhaps a haughty squaring of the shoulders, opens his mouth with: ‘what I see before me is ostensibly some manner of vase –” before he must inevitably close it again, because what is a vase until it is contextually understood by everyone listening? A decorative container typically without handles, but not necessarily, and used as ornament to a home, or as storage for fluid. There is a lot of contextual heavy-lifting a seemingly innocuous noun can imply. Some amount of shared understanding is necessary for the communication between two persons; a formal analysis cannot possibly operate without some level of context known to the people involved.

It is obvious what the two terms mean to indicate, yes; one tries to largely focus on analyzing the union of formal elements without much regard to context, and the other endeavors to assess an artwork in the framework of history without overfocusing on the effectiveness of the formal elements. However, under some Socratic scrutiny, it is reasonable to acknowledge that there is a large amount of interdependency that each one has on the other.

0 notes

Text

Reflection 5: Analysis of Frank Portelli’s ‘Maltese Arts and Crafts’.

Some key words that can describe my first impressions of this painting were solidity, strength, and schedule; even as my eye travelled across the left to the right, trying to take in all at once (whichnot easy), I was struck by the rectangular, stocky forms of the workers’ bodies and limbs, which gave me feelings of reassurance and strength. Unsurprisingly, they remind me of the way the villagers are back in my home country, in the mostly agrarian village in which my grandmother lives. The artist must have been familiar with workers; he gets right their hands most of all, something he doesn’t neglect to emphasise in almost each figure, because he knows – as I know – that their hands ( even the womens) are large, deft, sure of themselves, and rough from endless years of calluses. (In fact, it is when I put my hands in my grandmother’s that I know she’s finished more of a good day’s work within the green hours of one morning than I’ll ever do in a lifetime). The figures seem sculpted rather than painted; in many ways, they are reminiscent of brutalist sculptural works, full of angular planes and harsh edges, and represent the necessary stocky nature of working people, who are hewn into the way they are out of a hard life of wielding yokes, tilling land, and rearing animals.

Onto less subjective terms. It is apparent that the difficulty in reading the painting is intentional; this is a busy piece, aiming to depict a busy and chaotic workday with a feeling of constant forward momentum. The composition is subdivided into a continuum of planes - often competing in even saturation or hue - which disallow the eye to rest, sending it forward from point to point across a composition rich in diagonals and zig-zags, signifying movement, energy, vitality. It is important to note, however, that the composition is in no way ‘broken up’ - nor would it be right to describe the painting as discordant or unharmonious, though cacophonous it most surely is. The lines reach across from one plane to another, passing between and through the figures, signifying the workers’ codependibility on one other across trade or skill, as well as exemplifying a society that requires all of its constituents to play their role in order for the whole to thrive. The light often changes from day to night in the span of one beam of rectangles, possibly alluding to the workers’ ceaseless toil that necessarily must continue into the night. In short, the composition, though visibly sectioned into various components, is a collection of codependent and complimentary planes that reach into, inform, and complement each other, in much the same way the workers’ social cohesion is accomplished by each individual’s relationship to one another. The artist’s choice of dominant colour, a sort of serene emeral green-turned-turquoise - functions to subdue the boisterous energy of the burnt sienna and Indian-reds, while also acting as an intermediary agent between the depressive ultramarine and the more gleeful yellow. It negotiates between these clamourous parties, an intermediary mediator often bridging the hues and rectangular planes together, and diffusing an element of continuity throughout the entire composition.

Portelli’s piece then, presents a successful, endearing, and loving ode to the Maltese crafts and their architects. Though each worker lapses into their own specialized worlds, seen through the crystallized sectioning of planes, they also inter-depend on each other’s skills and work to see them through the day. In effect, though the cubistic approach typically breaks up and divides plain space, an interesting opposite effect occurs as unity and cohesion are felt throughout the painting.

0 notes

Text

Reflection 4: The Influence of Criticism on Interaction with Art

“How might an understanding of art criticism influence your interaction and perception of art in the future?”

I am inclined to suspect that deeper familiarity with critical art theories regarding my consuming of an artwork in the future will lead there to be a rather binary effect; it will either deepen my appreciation for a work of art, or my aversion to it. No in-between. Biographical analyses can enrich my understanding of an artwork by contextualizing the artist’s relationship to their artwork. Even should the interpreting of an artwork through a lens that may cause negative criticism be the case, (say, re-examining the motif of the reclining Venus through a Male Gaze framework), my appreciation for the work’s controversiality and versatility to be consumed differently under conflicting theories will only consolidate. Obviously, as there are exceptions to almost every rule, this will depend on a personal appraisal of the validity of the theory; if a new art criticism movement were to take centre stage that makes the claim that humanity has a moral right to disregard or dissemble any and all historical works of didactic art that contain allusions to morals we would regard as wrong today for example, or some other rot, I would most probably fold it into a paper airplaine and neatly launch it toward an incinerator.

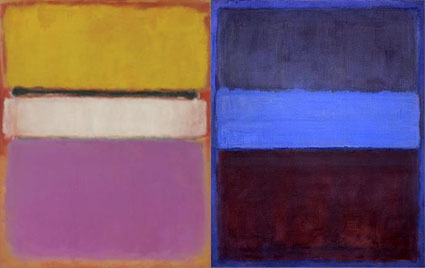

To take an example from Rothko; my appreciation for his works deepened after becoming more familiar with art theory (in the practical, colour-theory sense). Gaining a deeper understanding of colour theory led me to better understand that the man is a more than excellent thinker on the subject, and chooses his hue, tone, and value very deliberately, often expertly pairing two with one another in order to bring out intuitively excellent reactions between the two, and thereby, within the viewer. On the other hand, other forms of art theory, such as biographical analysis, could cause me to personally dislike an artwork; if I found out for example that a seemingly harmless poster of a pig was actually intended by the artist to caricaturize a nationality from a neighbouring country he hated, I regret to admit that my interaction and perception of the artwork would change, given that subjective feeling can often influence an objectively-intended analysis.

0 notes

Text

Reflection 3: Art Criticism and the Double-Edged Blade

“How do you think art criticism contributes to the development of art and artistic practices?”

Art criticism should be done with some amount of tact, imagination and (most importantly) not in excess, where the value of artist’s works are determined to the exclusion of new ideas or styles. A quick perusal of the unkind history of art criticism has shown us that art criticism has, for most of its formalized existence, not done that. However, it is also arguable that the effects of these periods of inflexible conformism to unyielding ideals pushed mankind to reach loftier and loftier heights, and begin to excel in some areas in much the same way a savant makes quick genius out of a few deft words or notes, but are unable to apply this level of skill outside of a very narrow range indeed.

The Ancient Greeks and Romans for example, and their rigid mania for mathematically perfect beauty, led them to create some of the most visually complex, dramatic, and hard-to-pull-off works of sculpture little seen before in history; which could arguably only have happened if they remained strictly devoted to attaining these intractable ideals. Inversely, their rigidity condemned experimentation, divergence, pluralism, the freedom to inquire - some of the most (I consider to be) important endeavours, not just in the field of the arts; but in the humanities, in science, in the pursuit of knowledge, or the engagement in practice or industry. As Neil Gaiman once said (making an analogy of music to writing):

Style is the stuff you get wrong. Because if you took him out - the person - everything would be played beautifully and perfectly — the falling away from perfection is what we recognize, and that makes style.

In a similar way, elements of personalisation, individualism, imperfection, subjectivity - should be principles that art criticism can (and should) defend and uphold, as it has shown itself capable of doing in the last century (relative to the macro timeline it is a small period; nevertheless), to give feminist critiques and its advocacy for pluralism as an example. A large array of 20th-century critics curated the reputations of a number of significant artists, such as with Rosenberg and De Kooning, or Greenberg and Pollock; demonstrating the significance art criticism still can have in modern times. It is therefore doubly important that in recognition and respect for this, the act of art criticism should be done with tact, imagination, and tolerance.

0 notes

Text

Reflection 2: Basis for Judgement

“Can you think of an example where you have informally critiqued an artwork? What were your bases for judgement?”

Personally, it is difficult to separate my experiences of art criticism from a formal setting, as most of the times I have engaged with this exercise has been in the context of formal art education. However, there are a few instances in which I have informally critiqued artworks that exemplify a personal subjective basis for critical judgement: which surprisingly, actually stemmed from criticising literature.

In the studying of poetry analysis, I was taught that - given the highly subjective and amorphous nature of poetry - a medium of writing which resists constraint, and can be highly experimental with almost everything (from meter, to rhyme, to verse structure, to physical form) - one’s primary purpose in the criticism of poetry is setting about determining what the poem ‘is after’. That one should avail oneself to analyze every hint and piece of information available, in order to build a case for what the objective of the work might be, and then to appraise how successful it was in the attempt.

In much the same way, I have come to realize that, before a formal study of art criticism practice, I evaluated most works I came across with largely the same philosophy. When presented with one of the Yves Klein blue monochromes in Rome for example, my impression was that if Klein’s intention can be reasonably inferred to be the sensory appreciation of purity and immaterial space by use of uniform colour, I believe he failed where Rothko succeeded; as I think the latter’s use of monumental scale, clever use of colour theory, and partnership of synthesising colours provoked a much more successful effect, both in the layman and the dabbler. Therefore, despite neither artists’ styles venturing too far into my liking, I did try to approach the criticising of an artwork by adopting the ‘don’t judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree’ mentality, and critiqued artworks (informally, to friends or family) based on my best understanding of the work’s - not necessarily the artist’s* - intention, which, given the nebulous quality of visual art, is admittedly much tougher to determine than in poetry.

*I mention this out of awareness of the ‘death of the author’ discourse’; whether much significance should be attributed to an artist’s or author’s intention if all works must by definition go through the wringer of our individually functioning, interpretive brains anyway. I adopt a more or less cowardly centrism wherein I order off the menu and assert that works themselves - separate from the artist - still have some measure of goal they want to deliver on, and can be criticised based on the measure of success of this. E.g. I cannot know for certain that Yves Klein’s intention is as mentioned above, but I can reasonably infer that the work made is not attempting to be a comedic graphic novelv strip, but some manner of conceptual commentary involving absoluteness of colour.

0 notes

Text

The Role of Art Criticism in Today's World

My understanding of the art critic’s impact in today’s world is frankly confusing and inherently contradictory. From research, it’s apparent that the role of an art critic in today’s world is described as a dead or dying thing, with only around ten contemporary critics in the United States able to get bread on their table from the job (according to Josh Baer in a conversation with Saltz). Others say, with no small derision and regret, that the wheel of the art market is directed by the covert hands of the art critics, who sit like bejeweled gargoyles at the top of the art food chain and live only to propagate a money-obsessed marketplace concerned with artworks insofar as their capacity to be investments. One thinks of Hughes in Nothing if Not Critical (Hughes, 1990 cited in: Gerry, 2012):

“So much of art – not all of it thank god, but a lot of it – has just become a kind of cruddy game for the self-aggrandisement of the rich and the ignorant.”

Then there is the middle-men; who, operating on the premise that the profession is indeed within its death throes, or that it is a rare profession to begin with, abandon the exercise of describing in pursuit of prescribing the appreciating value of the critic in light of this Ozymandian plight. In summary: assertion A is that critics have hold little to no sway nowadays, assertion B is that they have enough such that they generate a sort of monopoly within elite circles, and assertion C is that while art critics may be rare and few between, they are nowadays more important than ever due to their increasing scarcity. (Personally speaking, this fallaciously begs the question that they are inherently beneficial to the art world, fons et origo). Difficult though the exercise may be, I will endeavor to give a personal appraisal of the practice, using the classic pro-con model.

For fear of falling into cliché, I will not quote Anton Ego from Ratatouille, but in true pop fashion I will make reference to the spirit behind the movie’s words: the notion that the ‘new needs friends’. Art critics can give new voices a platform, and allow new styles, approaches, and artistic philosophies to take center stage, where they would otherwise have been drowned out by the dull totalitarianist clamor of consensus and trend.

In the classical sense, the role of the critic is to act as an intellectual mediator between an audience and the artwork; contextualizing, providing perspective, and deepening appreciation, if done well. It follows the hermeneutical tradition: the interpretation and comprehension of human intellectual work, ascribing meaning to the animating principle behind these actions, evaluating the merits and values of the artwork in terms of what it has affirmed or provided for the human race. This is well anthologized in the beginning of Eleni Gentou’s (2010) Subjectivity in Art History and Criticism:

“…the approach of the art historian should have a scientific character, aiming at objectively valid formulations, while the critic should give equal consideration to subjective factors, acknowledging international artistic values, often taking on the additional role of philosopher or theorist of art.”

In effect, this creates a certain incentive among those who practice art criticism to - for lack of a better term - ‘sell you the idea’ (of the artwork). Perceiving the glass as half full, this generates a type of literary criticism that becomes an artwork within itself. As Jonathan Jones (2012) said in praise of good old Robert Hughes to the Guardian, “[...]he made criticism look like literature”. This factor is really what delineates the critic from the historian; as Ackerman (1960) eloquently said: “The typical critic is a specialist in expressionistic prose, the historian in esoteric facts.”

Inversely perceiving the glass as half-empty, this also leads to a cult of a pithy, insipid and lazy appraisal of truly mediocre work, work which only can (and is) prettied up retroactively with pretty words. In this regard, critics can truly be the conman’s wet dream; they’ve thought up excuses for his meritless work before he’s even thought of them himself.

On a further note sympathetic to their craft however, the role of critiquing art is not without risk, despite general perception that the artist is more or less a trembling spring lamb offering its brave work to the reptilian jaws of the wicked critic. Art criticism in the past has endeavored to debase something contemporary to the period, that, in the long run, became treasured and admired by humanity - impressionism being the obvious example here. One age’s pejorative often becomes another age’s badge of honor, and with the convenience of retrospect, the world isn’t kind to critics on the wrong side of history. At the risk of inviting accusations of moral relativism, I will venture to say that we operate under the spirit of their time and that people are a bit too prone to thinking ‘I would have been on the right side of history had I been there’ for my liking. The same way they gnash their teeth and imagine that they would have saved Van Gogh’s work from obscurity and suicide had they just been there in time for his early (initially pretty terrible) work.

In summary, I have tried to paint a balanced portrait of art critics, if a bit magnanimous. They are perceived as parasitical by some, by others they are appreciated for the perceived artistic value of their writings - as such, the latter group is not really concerned about what the art critics do for Art inasmuch as how they do it. There are several traps that critics may fall into, such as the excessive defense of the old; the “[...]settled expectations and unquestioned presuppositions” (Kuspit, 2014), and to the contrary, a spineless adherence to anything and everything whose only virtue is that it's new in some way. One mustn’t think that we’re immunized against the error that the naysayers of the Impressionists fell into; at the same time, don’t let’s shut our prefrontal lobes down because one more artist decantered themselves into the currently already overfull and very sexy ‘questioned the boundaries of what art is’ pool. The illegitimacy of both utter skepticism and utter dogmatism is equally insupportable.

References

Ackerman, J.S. (1960). Art History and the Problems of Criticism. Daedalus, [online] 89(1), pp.253–263. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20026565 [Accessed 19 Oct. 2023].

Cargill, O. (1958). The Role of the Critic. College English, 20(3), p.105. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/371736.

Kuspit, D. B. (2014). Art criticism. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/art-criticism.

Development, P. (2023). Jerry Saltz | The Baer Faxt Podcast. [online] www.thebaerfaxtpodcast.com. Available at: https://www.thebaerfaxtpodcast.com/e/jerry-saltz/.

Gemtou, E. (2010). Subjectivity in Art History and Art Criticism. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 2(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v2n1.02.

Gerry (2012). Robert Hughes. [online] That’s How The Light Gets In. Available at: https://gerryco23.wordpress.com/2012/08/07/robert-hughes-greatest-art-critic-of-our-time/ [Accessed 16 Oct. 2023].

HOWE DOWNES, W. (2023). ART CRITICISM on JSTOR. [online] Jstor.org. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23938988 [Accessed 20 Oct. 2023].

Hughes, R. (2015). The Spectacle of Skill. Vintage.

Jones, J. (2012). Robert Hughes: The Greatest Art Critic of Our Time. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/aug/07/robert-hughes-greatest-art-critic. [Accessed 16 Oct. 2023].

Pepper, S.C. (2013). The Basis of Criticism in the Arts.

1 note

·

View note