Text

PC industry suffers as Microsoft severs link between Windows and hardware refreshes

New Post has been published on http://team77.com/pc-industry-suffers-as-microsoft-severs-link-between-windows-and-hardware-refreshes/

PC industry suffers as Microsoft severs link between Windows and hardware refreshes

The global PC market is set to decline by almost 1.9% over the next two years, according to Ranjit Atwal, research director at Gartner. “PC shipments will total 258 million units in 2019, a 0.6% decline from 2018,” he said. “Traditional PCs are set to decline by 3% in 2019 to total 189 million units.”

However, Gartner’s latest forecast suggests that between 2018 and 2012, sales of ultramobiles will increase by almost 20%.

Atwal said it has taken a while for the PC industry to offer compelling features such as instant on and all-day battery life on these types of device, which often have a far higher selling price than standard laptops.

He said the PC market is effectively saturated, but businesses will continue to buy mobile PCs even though the smartphone tends to be users’ primary mobile device. “A laptop is the device you use to create content,” he said.

Given that businesses will continue to provide end-users with laptop PCs, Windows 10 remains the dominant platform on which content creation-type work will run. Gartner predicted that Windows 10 will represent 75% of the professional PC market by 2021.

Windows 7 support is scheduled to end in January 2020, and for businesses, the Windows 10 migration will continue to drive a PC refresh. According to Gartner, while the US is now in the final phase of moving off Windows 7, China is still a few years away.

“By moving the Windows 10 migration to 2020, organisations increase the risk of remaining on an unsupported operating system.,” said Atwal.

“We are seeing businesses across the word migrating to Windows 10. It is a modern operating system and allows organisations to run cloud applications and provide security much more effectively.”

End of support for Windows 7

Support for Windows 7 will end in January 2020, after which organisations will have to buy a custom support contract if they want their Windows 7 systems supported. This situation mirrors the Windows XP end-of-support deadline, which occured in 2014.

“When XP support was pulled, a lot of government organisations were left on XP,” said Atwal. “They had to pay extra for support. Businesses do not want to be in this situation again, where they have to pay for one-off support of Windows 7.”

He pointed out that there is no option for organisations to skip a version because there will not be a Windows 11. “From now on, organisations will get consistent upgrades to the Windows operating system,” he said.

So, the migration from Windows 7 to Windows 10 is the last time IT departments will have to take a forklift approach to upgrading their desktop operating system, said Atwal. Organisations need to move to Windows 10, or they will fall behind, he said. For instance, Microsoft has aligned the upgrades of its cloud productivity suite, Office 365, to Windows 10.

But the main benefit of Windows 10 to IT is its improved back-end management, said Atwal. “You can operate and manage Windows more effectively once you are on Windows 10,” he added.

One example is that Microsoft now manages upgrades, said Atwal. Many organisations do not have a team that is permanently set up to upgrade the Windows operating system, so embarking on a new Windows operating system upgrade is a major IT project.

Such Windows upgrade projects should become a thing of the past if organisations entrust Microsoft to update their PC estates automatically, he said.

PC refresh

From a PC market perspective, Windows 10 disconnects the link between PC hardware and Windows operating system upgrades. Windows 10 is upgraded twice a year, which means business users will receive new operating system features every six months.

Atwal said he expected businesses to continue to upgrade PCs, but with more enterprise applications consumed as software as a service (SaaS), hardware upgrades are likely to be driven by wear and tear rather than the availability of a new PC operating system from Microsoft. “Given that the laptop is an important business tool, it will be upgraded,” he said.

0 notes

Text

JetStream DR cloud replication aims to make backup redundant

New Post has been published on http://team77.com/jetstream-dr-cloud-replication-aims-to-make-backup-redundant/

JetStream DR cloud replication aims to make backup redundant

JetStream software has announced general availability for its JetStream DR product, which allows continuous replication – as opposed to periodic snapshots – of VMware virtual machines (VMs) and data to public cloud locations.

The product, aimed at service providers and enterprises, allows customers to failover to operations from the cloud in the case of an outage with an RPO (recovery point objective) of near zero.

JetStream DR also works with S3-based object storage and can continuously replicate that data from on-premise locations to public clouds.

JetSteam originated as FlashSoft and went through a number of acquisitions, with a formative period being one in which it developed technology used by VMware in its APIs for I/O filtering (VAIO).

At its core, this allows for any I/O stream to be intercepted between the VM and virtual disk in real time, with intelligence then being applicable to that flow of data.

So, for example, JetStream has a product called Accelerate, in which IO Filter can select whether data should be served/stored on cache or underlying storage, with claimed application performance of 3x to 5x.

Meanwhile, JetStream Migrate allows for data to be migrated in near real time from on-premise VMware deployments to the public cloud.

This can be carried out without shutdown during transfer because IO Filter can move the bulk of the VM and disk and then keep track of data written concurrently to build the VM and disk as soon as possible afterwards.

JetStream DR aims to allow for “data protection as a true cloud service”, said company president Rich Petersen.

“Data protection need to be elastic and dynamically consumable. So, for example, if you have Nutanix on-premise, you need to replicate to Nutanix in the cloud. It’s the same for other HCI providers and for [VMware] VSAN.”

Instead, JetStream DR allows users to replicate VMware VMs and data to any cloud service and to failover to it in case of a disaster recovery scenario.

Petersen contrasts his company’s product with backup in general and in particular with offerings from Veeam and Druva. Unlike those products, JetStream is continuous and not dependent on periodic snapshots or backups.

A similar service can be applied to on-premise S3 object storage data, although re-hydration of stored data will take longer than for VMs.

There are no plans to expand the product to support Hyper-V and KVM. That will be “years away”, said Petersen.

0 notes

Text

Boeing 737 MAX Crash Sends Market Cap Lower

New Post has been published on http://ritzywordpressthemes.com/boeing-737-max-crash-sends-market-cap-lower/

Boeing 737 MAX Crash Sends Market Cap Lower

Every month, AeroAnalysis International covers the orders and deliveries for Boeing (BA) and Airbus (OTCPK:EADSY, OTCPK:EADSF). Now, there’s a lot more than just orders and deliveries. Some subjects are worthy of more detailed analysis, and some are not. The subjects that are not are not necessarily unimportant. Therefore, AeroAnalysis has been running a monthly series that bundles some of the most interesting news items that do not justify a separate article or deserve to be mentioned again. You can read the February report here. In this report, some news items from March will be highlighted.

Source: Axios

Share Price Development in March

In March 2019, Boeing’s shares lost 13.4% compared to a 13.6% gain a month earlier. Boeing’s shares significantly underperformed the Dow Jones, which was flat for the month.

The reach for the downward pressure on Boeing shares during the month is clear: The crash with the Boeing 737 MAX 8 from Ethiopian Airlines marking the second fatal crash.

A look at some price target announcements in March:

Argus initially gave Boeing shares a $460 with a buy rating but reverted to a Hold rating after the Ethiopian Airlines crash with a $371.30 price target.

Edward Jones downgraded Boeing shares from a Buy to Hold with a $300 price target.

DZ Bank downgraded Boeing shares from a Buy to Hold with a $300 price target.

Norddeutsche Landesbank set a $300 on Boeing shares with a Sell rating.

Tigres Financial reiterated its Buy rating.

Citi Group resumed with a Buy rating.

What we did see in the aftermath of the second fatal crash with the Boeing 737 MAX is that analyst sentiment deteriorated, which shouldn’t come as a surprise. This stepdown in sentiment was expected, but it remains to be seen whether going forward, with fixes implemented and a return to service for the MAX, this negative sentiment will endure.

Commercial Airplanes News

Source: Boeing

During the month of March, the crash with the Boeing 737 MAX captured most attention. Boeing shares declined in value after the crash on fears that there is a design flaw on the Boeing 737 MAX. In the aftermath of the first crash, I already pointed out that the MCAS design might not have been robust and that it was unclear as to how this part of the speed trim system was certified by the FAA and aviation administrations around the globe. While I consider this a shortcoming on Boeing’s side, even with a preliminary report out, it is not clear why the pilots flew the aircraft at a very high speed which might have made regaining control over the aircraft nearly impossible. Currently, Boeing is working on a fix, which will likely be closely eyeballed by administrations around the globe because confidence in Boeing as well as the FAA has been severely dented. Until the fix is approved, the fleet of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft will remain on the ground and no deliveries will occur. The crash is likely going to impact Boeing’s earnings for the simple reason that the grounding is costing money, possibly beyond the amount Boeing is covered for by insurers, and revenue is being delayed due to the production stop resulting in working capital increases.

I’ve written a few reports on the subject, which you can read here:

In the aftermath of the two crashes, Indonesian carriers are looking for cancellations of their direct orders for the MAX with Boeing and agreements with lessors while Boeing is being probed.

The only other noteworthy news item regarding commercial aircraft was the order for 20 Boeing 787-9s from Lufthansa (OTCQX:DLAKF). Boeing had been battling Airbus for an order for months, and Lufthansa eventually ended up splitting the order between both jet makers.

Investment News

Source: The Boeing Company

Fitting its after-sales and digital solutions strategy, Boeing acquired ForeFlight, a leading provider of innovative mobile and web-based aviation applications.

ForeFlight has partnered with Boeing for the past two years to bring aviators Jeppesen’s aeronautical data and charts through ForeFlight’s popular mobile platforms. Now, the teams will integrate talent and offerings to bring innovative, expanded digital solutions to all segments of the aviation industry.

As part of the joint venture between Boeing and Embraer (ERJ), Boeing announced three leadership moves aimed at further strengthening the company’s global presence and partnerships:

Marc Allen has been named senior vice president of Boeing and president of Embraer Partnership and Group Operations;

Sir Michael Arthur has been named president of Boeing International;

John Slattery announced as president and chief executive officer of the commercial aviation and services joint venture between Boeing and Embraer.

Global Services

Source: Aviation Jobs and Aviation Employment – AviationCV.com

In March, there was no notable news for Boeing’s Global Services division.

Defense News

Source: The Boeing Company

For Boeing Defense, there were a couple of news events. A program capturing some negative attention was the KC-46A. In February, the USAF stopped accepting tankers from Boeing as foreign object debris was found inside the tankers. Deliveries resumed in March, which should have been a good thing were it not that the USAF halted deliveries again in early April. While the second delivery stop is an April news event, I think it is important to highlight it in this report, which covers the March news events as well.

More positive news came from Boeing’s F-18 fighter jet program. Boeing was awarded a three-year contract award for 78 F/A-18 Block III Super Hornets. The contract is valued $4B and is expected to save US taxpayer $395 million.

A major milestone was also achieved by the Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 DEFIANT; The Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 DEFIANT™ helicopter achieved first flight. The helicopter is participating in the Army’s Joint Multi-Role-Medium Technology Demonstrator program. Data from DEFIANT will help the Army develop requirements for new utility helicopters expected to enter service in the early 2030s. This flight marks a key milestone for the Sikorsky-Boeing team and is the culmination of significant design, simulation, and test activity to further demonstrate the capability of the X2 Technology.

X2 Technology is scalable to a variety of military missions such as attack and assault, long-range transportation, infiltration and resupply. DEFIANT is the third X2®aircraft in less than 10 years.

During the month, there also was a milestone for the Ground-based Midcourse Defense [GMD] system as the US Missile Defense Agency and Boeing for the first time launched two GMD system interceptors to destroy a threat-representative target, validating the fielded system protects the United States from intercontinental ballistic missiles.

In the test, one interceptor struck the target in space. The second interceptor observed that intercept before destroying additional debris to ensure missile destruction. The test is known as a “two-shot salvo” engagement. The target launched from Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific Ocean while the interceptors launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

Conclusion

Without doubt, March was a bad month for Boeing. For a company’s share to perform well, you ultimately need a good product, coupled with good execution or you need good execution to make a good product. With the second crash of a Boeing 737 MAX, it does seem like Boeing has failed miserably on the execution part, which I expect will affect their current year performance.

Boeing had some highlights as well with a milestone order from Lufthansa and a production contract for its Super Hornet fighter, but not nearly enough to mitigate the pressure the Boeing 737 MAX cash cow is currently putting on Boeing. During the month of March, Boeing’s market cap declined by $33.4B. This decline cannot be fully explained by closing math (there is no calculation to support the cap decline), but such a big decline in market cap is perfectly understandable, given the importance of the Boeing 737 program to Boeing and the uncertainty regarding the aircraft. I expect that the Boeing 737 MAX will eventually be approved for flight again, and as investors and stakeholders around the world regain confidence, Boeing should see recovery in its market cap. In fact, in the first days of March, nearly $9B in market cap was recovered. At the end of the day, Boeing should be learning lessons from this.

If you enjoyed reading this article, don’t forget to hit the “Follow” button at the top of this page (below the article title) to receive updates for my upcoming articles.

If you like our regular coverage, please consider joining The Aerospace Forum which gives you more indepth tools to understand the industry, access to over 750+ previously published reports and ways (Live chat with the group and one-on-one conversations) to discuss the aerospace industry. *Start your free trial today*

Disclosure: I am/we are long BA, EADSF. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

0 notes

Text

Boeing 737 MAX Crash Sends Market Cap Lower

New Post has been published on http://croopdiseno.com/boeing-737-max-crash-sends-market-cap-lower/

Boeing 737 MAX Crash Sends Market Cap Lower

Every month, AeroAnalysis International covers the orders and deliveries for Boeing (BA) and Airbus (OTCPK:EADSY, OTCPK:EADSF). Now, there’s a lot more than just orders and deliveries. Some subjects are worthy of more detailed analysis, and some are not. The subjects that are not are not necessarily unimportant. Therefore, AeroAnalysis has been running a monthly series that bundles some of the most interesting news items that do not justify a separate article or deserve to be mentioned again. You can read the February report here. In this report, some news items from March will be highlighted.

Source: Axios

Share Price Development in March

In March 2019, Boeing’s shares lost 13.4% compared to a 13.6% gain a month earlier. Boeing’s shares significantly underperformed the Dow Jones, which was flat for the month.

The reach for the downward pressure on Boeing shares during the month is clear: The crash with the Boeing 737 MAX 8 from Ethiopian Airlines marking the second fatal crash.

A look at some price target announcements in March:

Argus initially gave Boeing shares a $460 with a buy rating but reverted to a Hold rating after the Ethiopian Airlines crash with a $371.30 price target.

Edward Jones downgraded Boeing shares from a Buy to Hold with a $300 price target.

DZ Bank downgraded Boeing shares from a Buy to Hold with a $300 price target.

Norddeutsche Landesbank set a $300 on Boeing shares with a Sell rating.

Tigres Financial reiterated its Buy rating.

Citi Group resumed with a Buy rating.

What we did see in the aftermath of the second fatal crash with the Boeing 737 MAX is that analyst sentiment deteriorated, which shouldn’t come as a surprise. This stepdown in sentiment was expected, but it remains to be seen whether going forward, with fixes implemented and a return to service for the MAX, this negative sentiment will endure.

Commercial Airplanes News

Source: Boeing

During the month of March, the crash with the Boeing 737 MAX captured most attention. Boeing shares declined in value after the crash on fears that there is a design flaw on the Boeing 737 MAX. In the aftermath of the first crash, I already pointed out that the MCAS design might not have been robust and that it was unclear as to how this part of the speed trim system was certified by the FAA and aviation administrations around the globe. While I consider this a shortcoming on Boeing’s side, even with a preliminary report out, it is not clear why the pilots flew the aircraft at a very high speed which might have made regaining control over the aircraft nearly impossible. Currently, Boeing is working on a fix, which will likely be closely eyeballed by administrations around the globe because confidence in Boeing as well as the FAA has been severely dented. Until the fix is approved, the fleet of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft will remain on the ground and no deliveries will occur. The crash is likely going to impact Boeing’s earnings for the simple reason that the grounding is costing money, possibly beyond the amount Boeing is covered for by insurers, and revenue is being delayed due to the production stop resulting in working capital increases.

I’ve written a few reports on the subject, which you can read here:

In the aftermath of the two crashes, Indonesian carriers are looking for cancellations of their direct orders for the MAX with Boeing and agreements with lessors while Boeing is being probed.

The only other noteworthy news item regarding commercial aircraft was the order for 20 Boeing 787-9s from Lufthansa (OTCQX:DLAKF). Boeing had been battling Airbus for an order for months, and Lufthansa eventually ended up splitting the order between both jet makers.

Investment News

Source: The Boeing Company

Fitting its after-sales and digital solutions strategy, Boeing acquired ForeFlight, a leading provider of innovative mobile and web-based aviation applications.

ForeFlight has partnered with Boeing for the past two years to bring aviators Jeppesen’s aeronautical data and charts through ForeFlight’s popular mobile platforms. Now, the teams will integrate talent and offerings to bring innovative, expanded digital solutions to all segments of the aviation industry.

As part of the joint venture between Boeing and Embraer (ERJ), Boeing announced three leadership moves aimed at further strengthening the company’s global presence and partnerships:

Marc Allen has been named senior vice president of Boeing and president of Embraer Partnership and Group Operations;

Sir Michael Arthur has been named president of Boeing International;

John Slattery announced as president and chief executive officer of the commercial aviation and services joint venture between Boeing and Embraer.

Global Services

Source: Aviation Jobs and Aviation Employment – AviationCV.com

In March, there was no notable news for Boeing’s Global Services division.

Defense News

Source: The Boeing Company

For Boeing Defense, there were a couple of news events. A program capturing some negative attention was the KC-46A. In February, the USAF stopped accepting tankers from Boeing as foreign object debris was found inside the tankers. Deliveries resumed in March, which should have been a good thing were it not that the USAF halted deliveries again in early April. While the second delivery stop is an April news event, I think it is important to highlight it in this report, which covers the March news events as well.

More positive news came from Boeing’s F-18 fighter jet program. Boeing was awarded a three-year contract award for 78 F/A-18 Block III Super Hornets. The contract is valued $4B and is expected to save US taxpayer $395 million.

A major milestone was also achieved by the Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 DEFIANT; The Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 DEFIANT™ helicopter achieved first flight. The helicopter is participating in the Army’s Joint Multi-Role-Medium Technology Demonstrator program. Data from DEFIANT will help the Army develop requirements for new utility helicopters expected to enter service in the early 2030s. This flight marks a key milestone for the Sikorsky-Boeing team and is the culmination of significant design, simulation, and test activity to further demonstrate the capability of the X2 Technology.

X2 Technology is scalable to a variety of military missions such as attack and assault, long-range transportation, infiltration and resupply. DEFIANT is the third X2®aircraft in less than 10 years.

During the month, there also was a milestone for the Ground-based Midcourse Defense [GMD] system as the US Missile Defense Agency and Boeing for the first time launched two GMD system interceptors to destroy a threat-representative target, validating the fielded system protects the United States from intercontinental ballistic missiles.

In the test, one interceptor struck the target in space. The second interceptor observed that intercept before destroying additional debris to ensure missile destruction. The test is known as a “two-shot salvo” engagement. The target launched from Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific Ocean while the interceptors launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

Conclusion

Without doubt, March was a bad month for Boeing. For a company’s share to perform well, you ultimately need a good product, coupled with good execution or you need good execution to make a good product. With the second crash of a Boeing 737 MAX, it does seem like Boeing has failed miserably on the execution part, which I expect will affect their current year performance.

Boeing had some highlights as well with a milestone order from Lufthansa and a production contract for its Super Hornet fighter, but not nearly enough to mitigate the pressure the Boeing 737 MAX cash cow is currently putting on Boeing. During the month of March, Boeing’s market cap declined by $33.4B. This decline cannot be fully explained by closing math (there is no calculation to support the cap decline), but such a big decline in market cap is perfectly understandable, given the importance of the Boeing 737 program to Boeing and the uncertainty regarding the aircraft. I expect that the Boeing 737 MAX will eventually be approved for flight again, and as investors and stakeholders around the world regain confidence, Boeing should see recovery in its market cap. In fact, in the first days of March, nearly $9B in market cap was recovered. At the end of the day, Boeing should be learning lessons from this.

If you enjoyed reading this article, don’t forget to hit the “Follow” button at the top of this page (below the article title) to receive updates for my upcoming articles.

If you like our regular coverage, please consider joining The Aerospace Forum which gives you more indepth tools to understand the industry, access to over 750+ previously published reports and ways (Live chat with the group and one-on-one conversations) to discuss the aerospace industry. *Start your free trial today*

Disclosure: I am/we are long BA, EADSF. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

0 notes

Text

Monthly Review Of DivGro: March 2019

New Post has been published on http://unchainedmusic.com/monthly-review-of-divgro-march-2019/

Monthly Review Of DivGro: March 2019

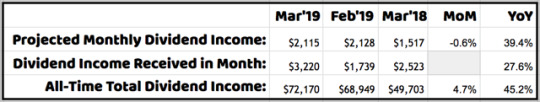

Welcome to the March review of DivGro, my portfolio of dividend growth stocks. Quarter-ending months are exciting, as many of the stocks I own pay dividends in these months and I usually set a new record for monthly dividend income in quarter-ending months.

March did not disappoint. I received dividends totaling $3,220 from 43 stocks in my portfolio, a new record for monthly dividend income! Year over year, DivGro’s dividend income increased by 28%. So far in 2019, I’ve collected $6,724 in dividends or about 27% of my 2019 goal of $25,200.

Looking at how the month’s activities impacted DivGro’s projected annual dividend income (PADI), I note that five DivGro stocks announced dividend increases in March. Additionally, I opened one new position and added shares to five existing positions. On the other hand, I closed out one high-yielding position. Unfortunately, the net result of these changes is that projected annual dividend income (PADI) decreased by about 0.6% in March. Year over year, PADI increased by 39%.

DivGro’s PADI now stands at $25,376, which means I can expect to receive $2,115 in dividend income per month, on average, in perpetuity, assuming the status quo is maintained. Of course, I expect the companies I’ve invested in not only to continue to pay dividends but to also increase them over time. Also, until I retire, I hope to continue reinvesting all dividends, so DivGro’s PADI should continue to grow through dividend growth and through compounding.

Dividend Income

In March, I received a total of $3,220 in dividend income from 43 different stocks:

Following is a list of the dividends I collected in March:

Aflac (AFL) — income of $27.00

Amgen (AMGN) — income of $36.25

Broadcom (AVGO) — income of $53.00

Boeing (BA) — income of $41.10

BlackRock (BLK) — income of $115.50

Cummins (CMI) — income of $57.00

Chevron (CVX) — income of $28.56

Dominion Energy (D) — income of $91.75

Digital Realty Trust (DLR) — income of $48.60

EPR Properties (EPR) — income of $18.75

Eversource Energy (ES) — income of $53.50

Extra Space Storage (EXR) — income of $47.30

Ford Motor (F) — income of $300.00

Gilead Sciences (GILD) — income of $126.00

Home Depot (HD) — income of $81.60

Honeywell International (HON) — income of $41.00

International Business Machines (IBM) — income of $47.10

Intel (INTC) — income of $163.81

International Paper (IP) — income of $50.00

Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) — income of $111.60

Lockheed Martin (LMT) — income of $30.80

Main Street Capital (MAIN) — income of $146.26

McDonald’s (MCD) — income of $31.32

3M (MMM) — income of $36.00

Microsoft (MSFT) — income of $46.00

NextEra Energy (NEE) — income of $31.25

AllianzGI Equity & Convertible Income Fund (NIE) — income of $380.00

Realty Income (O) — income of $56.38

PepsiCo (PEP) — income of $18.55

Pfizer (PFE) — income of $72.00

Public Storage (PSA) — income of $60.00

Ross Stores (ROST) — income of $25.50

Stanley Black & Decker (SWK) — income of $33.00

TJX (TJX) — income of $39.00

T. Rowe Price (TROW) — income of $152.00

Travelers (TRV) — income of $77.00

UnitedHealth (UNH) — income of $36.00

Union Pacific (UNP) — income of $35.20

United Parcel Service (UPS) — income of $33.60

Visa (V) — income of $4.25

Valero Energy (VLO) — income of $166.50

Walgreens Boots Alliance (WBA) — income of $88.00

Exxon Mobil (XOM) — income of $82.00

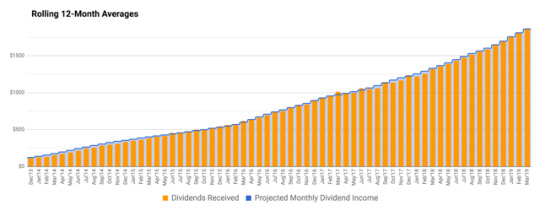

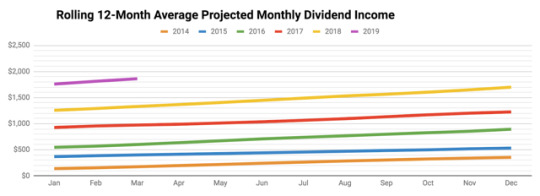

The following chart shows DivGro’s monthly dividends plotted against PMDI. Quarter-ending months are huge outliers:

This is one reason that I now create a rolling 12-month average of dividends received (the orange bars) plotted against a rolling 12-month average of PMDI (the blue, staggered line):

While it would be nicer if dividends were distributed more evenly, it is not something that would drive my investment decisions.

Dividend Changes

In March, the following stocks announced dividend increases:

General Dynamics (GD) — an increase of 9.68%

Realty Income — an increase of 0.22%

Ross Stores — an increase of 13.33%

Raytheon (RTN) — an increase of 8.65%

W.P. Carey (WPC) — an increase of 0.19%

These changes will increase DivGro’s PADI by about $39.

I like seeing dividend increases above 7% and three of the five increases top my expectations. As for the REITs O and WPC, they announce dividend increases multiple times per year. O’s year-over-year increase is 2.96%, whereas WPC’s year-over-year increase is 1.67%.

Transactions

Here is a summary of my transactions in March:

Merck (MRK) — new position of 30 shares

After opening a small position in Chevron (CVX) in December 2018, MRK was the highest ranked stock in the top 50 holdings of dividend ETFs not in my DivGro portfolio. MRK ranked higher on an aggregate score than several of my Health Care sector holdings and, according to Simply Safe Dividends, MRK has a Very Safe dividend safety score of 98.

I opened a relatively small position of 30 shares at $80.52 per share, as MRK is not trading at my preferred discount to fair value of at least 10%. With this opening position, I’ll be able to track MRK more closely and look for opportunities to add shares at a better valuation.

Omega Healthcare Investors (OHI) — sold 250 shares and closed position

I decided to close my position in OHI on concerns about the declining fundamentals of OHI’s skilled nursing tenants. OHI has a Borderline Safe dividend safety score of 47, yet the REIT’s yield of 7%+ provides some compensation for the increased risk. Unfortunately, OHI broke a streak of 21 consecutive quarters of dividend increases when it froze its dividend last April, and unless OHI declares another dividend increase in 2019, it will be removed from the CCC list of dividend growth stocks.

It turns out my closing trade was about two weeks premature, as OHI closed at a 30-day high of $38.31 on 28 March. Nevertheless, my closing price of $35.90 secured a net gain of 29% or about 18% annualized.

To (somewhat) make up for the $660 in annual dividends I gave up by closing my OHI position, I added shares to several existing positions trading at favorable comparative yields.

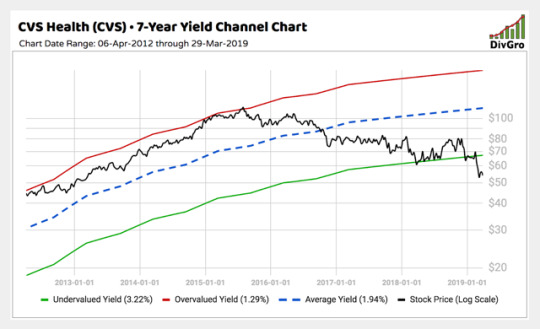

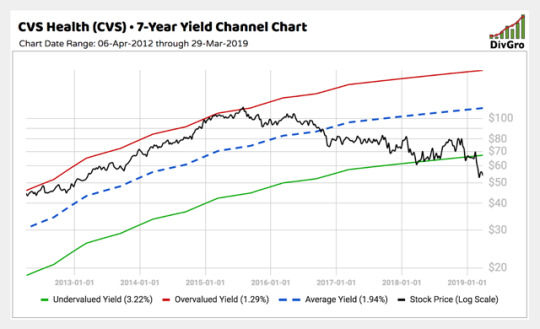

CVS Health (CVS) — added 50 shares and increased position to 200 shares

CVS continues to struggle and now is trading about 34% below its 52-week high. I paid $53.49 per share and lowered my average cost basis to $65.16. CVS froze its dividend after buying Aetna, though Simply Safe Dividends still considers the dividend Safe with a dividend safety score of 75.

I believe CVS will be fine in the long term, so the current yield is just too compelling to pass up, as illustrated in this 7-year yield channel chart:

Home Depot — added 10 shares and increased position to 60 shares

Honeywell International — added 10 shares and increased position to 60 shares

Iron Mountain (NYSE:IRM) — added 50 shares and increased position to 200 shares

3M — added 15 shares and increased position to 40 shares

HD‘s dividend safety score is 90 (Very Safe) while the stock’s current dividend yield of 2.71% is 29% above its 5-year average of 2.11%, according to Simply Safe Dividends. I paid $182.11 per share, slightly lowering my average cost basis in the process. The stock’s dividend growth is stellar, with 5-year and 20-year dividend growth rates of 22%.

I also added 10 shares to my HON position, which is deemed a Very Safe dividend growth stock with a dividend safety score of 98. HON is trading at about fair value. Honeywell reported solid Q4’18 results and the management team increased their guidance for fiscal 2019. I think the stock is a great long term hold, though it is vulnerable to market cyclicality.

IRM‘s dividend yield of 6.8% is about 11% above its 5-year average dividend yield of 6.13%. While the REIT’s dividend safety score is on the low end at 52 (Borderline Safe), I think the 6.8% yield compensates me sufficiently for the somewhat higher risk. I paid $34.86 per share and I notice the stock is now trading above $36 per share, so my timing seemed to be good.

Finally, it is not often that one can buy MMM at a discount to fair value. I missed an even better opportunity in December 2018, but I’m happy that I grabbed 15 shares at $206.08 in March. The stock now trades at $216 per share. MMM has a Very Safe dividend safety score of 86 and boasts a 5-year dividend growth rate of 16%.

The net effect of my March transactions is that DivGro’s PADI decreased by about $198. However, I believe my portfolio’s risk profile has improved in the process and I’m happy that I replaced the somewhat riskier OHI with safer alternatives.

Markets

Here is a summary of various market indicators, showing the changes over the last month:

In March, the DOW 30 increased slightly, the S&P 500 increased by 1.79%, and the NASDAQ increased by 2.61%. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note fell to 2.414%, while CBOE’s measure of market volatility, the VIX, decreased to 13.71.

Portfolio Statistics

Based on the total capital invested and the portfolio’s current market value, DivGro has delivered a simple return of about 47% since inception. In comparison, DivGro’s IRR (internal rate of return) is 14.5%. (IRR takes into account the timing and size of deposits since inception, so it is a better measure of portfolio performance).

I track the yield on cost (YoC) for individual stocks, as well as an average YoC for my portfolio. DivGro’s average YoC decreased from 3.98% last month to 3.92% this month.

On the other hand, DivGro’s projected annual yield is 4.73%. This is down from last month’s value of 4.84%. I calculate the projected annual yield by dividing PADI ($25,376) by the total amount invested.

Percentage payback relates dividend income to the amount of capital invested. DivGro’s average percentage payback is 13.5%, up from last month’s 13.1%.

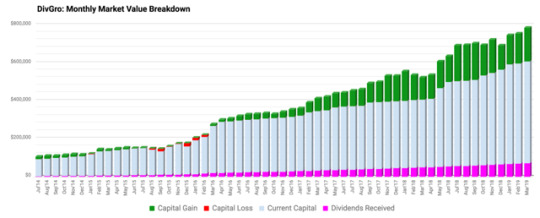

Here’s a chart showing DivGro’s market value breakdown. Dividends are plotted at the base of the chart so we can see them grow over time:

Looking Ahead

I’ve been working on creating a database of weekly dividend yields covering a period of 12 years. For now, the database covers dividend-paying stocks in my portfolio. In time, I’d like to add high-quality dividend growth stocks I don’t yet own.

Maintaining the database will allow me to create yield channel charts at any time to help guide investment decisions. Furthermore, I’ll be able to do a quick fair value estimate for stocks in the database by comparing the current dividend yield with the historical average dividend yield over a period of, say, five years.

I’m hoping to get back to writing monthly DivGro Pulse articles and share yield channel charts of stocks trading at or near extreme historical yields.

Please see my Performance page for various visuals summarizing DivGro’s performance.

Thanks for reading and take care, everybody!

Disclosure: I am/we are long AAPL, ABBV, ADM, AFL, AMGN, APD, AVGO, BA, BLK, CB, CMCSA, CMI, CSCO, CVS, CVX, D, DGX, DIS, DLR, EPR, ES, EXR, FDX, FRT, GD, HD, HON, HRL, IBM, INTC, IP, IRM, ITW, JNJ, JPM, KO, LMT, LOW, MAIN, MCD, MDT, MMM, MO, MRK, MSFT, NEE, NNN, O, PEP, PFE, PG, PM, ROST, RTN, SBUX, SKT, SPG, SWK, T, TJX, TROW, TRV, TXN, UNH, UNP, UPS, V, VLO, VZ, WBA, WEC, WPC, XOM. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

0 notes

Text

The Math of How Crickets, Starlings and Neurons Sync Up

New Post has been published on http://unchainedmusic.com/the-math-of-how-crickets-starlings-and-neurons-sync-up/

The Math of How Crickets, Starlings and Neurons Sync Up

When the incoherent claps of a crowd suddenly become a pulse, as everyone starts clapping in unison, who decided? Not you; not anyone. Crickets sing in synchrony; metronomes placed side by side sway into lockstep; some fireflies blink together in the dark. All across the United States, the power grid operates at 60 hertz, its innumerable tributaries of alternating current synchronizing of their own accord. Indeed, we live because of synchronization. Neurons in our brains fire in synchronous patterns to operate our bodies and minds, and pacemaker cells in our hearts sync up to generate the beat.

Quanta Magazine

About

Original story reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent publication of the Simons Foundation, whose mission is to enhance public understanding of science by covering research developments and trends in mathematics and the physical and life sciences.

Objects with rhythms naturally synchronize. Yet the phenomenon went entirely undocumented until 1665, when the Dutch physicist and inventor Christiaan Huygens spent a few days sick in bed. A pair of new pendulum clocks—a kind of timekeeping device that Huygens invented—hung side by side on the wall. Huygens noticed that the pendulums swung exactly in unison, always lurching toward each other and then away. Perhaps pressure from the air was synchronizing their swings? He conducted various experiments. Standing a table upright between the clocks had no effect on their synchronization, for instance. But when he rehung the clocks far apart or at right angles to each other, they soon fell out of phase. Huygens eventually inferred that the clocks’ “sympathy,” as he called it, resulted from the kicks that their swings gave each other through the wall.

When the left pendulum swings left, it kicks the wall and the other pendulum rightward, and vice versa. The clocks kick each other around until they and the wall attain their most stable, relaxed state. For the pendulums, the most stable behavior is to move in opposite directions, so that each pushes the other in the direction it’s already going, the way you push a child on a swing. And this is also easiest for the wall; it no longer moves at all, because the pendulums are giving it equal and opposite kicks. Once in this self-reinforcing, synchronous state, there’s no reason for the system to deviate. Many systems synchronize for similar reasons, with kicks replaced by other forms of influence.

Christiaan Huygens’ sketch of an experiment with a pair of pendulum clocks (top), and his attempt to understand why they synchronize (bottom). “B has gone again through the position BD when A is at AG, whereby the suspension A is drawn to the right, and therefore the vibration of pendulum A is being accelerated,” he wrote. “B is again in BK when A has been returned to position AF, whereby the suspension of B is drawn to the left, and therefore the vibration of pendulum B slows down. And so, when the vibration of pendulum B is steadily slowing down, and A is being accelerated, it is necessary that … they should move together in opposite beats….”

Reproduced from Oeuvres complètes de Christiaan Huygens (1888); Huygens’ passage from Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences (2002)

Another Dutchman, Engelbert Kaempfer, traveled to Thailand in 1690 and observed the local fireflies flashing simultaneously “with the utmost regularity and exactness.” Two centuries later, the English physicist John William Strutt (better known as Lord Rayleigh) noticed that standing two organ pipes side by side can “cause the pipes to speak in absolute unison, in spite of inevitable small differences.” Radio engineers in the 1920s discovered that wiring together electrical generators with different frequencies forced them to vibrate with a common frequency—the principle behind radio communication systems.

It wasn’t until 1967 that the pulsating chirps of crickets inspired the American theoretical biologist Art Winfree to propose a mathematical model of synchronization. Winfree’s equation was too difficult to solve, but in 1974, a Japanese physicist named Yoshiki Kuramoto saw how to simplify the math. Kuramoto’s model described a population of oscillators (things with rhythms, like metronomes and heartbeats) and showed why coupled oscillators spontaneously synchronize.

Kuramoto, then 34, had little prior experience in nonlinear dynamics, the study of the feedback loops that tangle together variables in the world. When he showed his model to experts in the discipline, they failed to grasp its significance. Discouraged, he set the work aside.

Five years later, Winfree came across a précis of a talk Kuramoto had given about his model and realized that it offered a revolutionary new understanding of a subtle phenomenon that pervades the world. Kuramoto’s math has proved versatile and extendable enough to account for synchronization in clusters of neurons, fireflies, pacemaker cells, starlings in flight, reacting chemicals, alternating currents and myriad other real-world populations of coupled “oscillators.”

“I didn’t imagine at all that my model would have a wide applicability,” said Kuramoto, now 78, by email.

But, as ubiquitous as Kuramoto’s model became, any illusions physicists had of understanding synchronization shattered in 2001. Once again, Kuramoto was at the center of the action.

Different Strokes

In Kuramoto’s original model, an oscillator can be pictured as an arrow that rotates in a circle at some natural frequency. (If it’s a firefly, it might flash every time the arrow points up.) When a pair of arrows are coupled, the strength of their mutual influence depends on the sine of the angle between their pointing directions. The bigger this angle, the bigger the sine, and therefore the stronger their mutual influence. Only when the arrows point in parallel directions, and rotate together, do they stop pulling on each other. Thus, the arrows will drift until they find this state of synchrony. Even oscillators that have different natural frequencies, when coupled, reach a compromise and oscillate in tandem.

But that basic picture only explains the onset of global synchronization, where a population of oscillators all do the same thing. As well as being the simplest kind of sync, “there are plenty of examples of global synchronization; that’s why people paid so much attention to that,” said Adilson Motter, a physicist at Northwestern University in Chicago, and a leading sync scientist. “But in 2001, Kuramoto discovered something very different. And that’s where the story of different states starts.”

Yoshiki Kuramoto, a professor of physics at Kyoto University, developed the famous Kuramoto model of synchronization in the 1970s and co-discovered the chimera state in 2001, again revolutionizing the understanding of sync.

Tomoaki Sukezane

It was Kuramoto’s Mongolian post-doc, Dorjsuren Battogtokh, who first noticed a new kind of synchronous behavior in a computer-simulated population of coupled oscillators. The identical oscillators, which were all identically coupled to their neighbors, had somehow split into two factions: Some oscillated in sync, while the rest drifted incoherently.

Kuramoto presented his and Battogtokh’s discovery at a 2001 meeting in Bristol, but the result didn’t register in the community until Steven Strogatz, a mathematician at Cornell University, came across it in the conference proceedings two years later. “When I came to understand what I was seeing in the graphics, I didn’t really believe it,” Strogatz said.

“What was so weird,” he explained, “was that the universe looks the same from every place” in the system. And yet the oscillators responded differently to identical conditions, some ganging together while the rest went their own way, as if not coupled to anything at all. The symmetry of the system “was broken,” Strogatz said, in a way that “had never been seen before.”

Strogatz and his graduate student Daniel Abrams, who now studies synchronization as a professor at Northwestern, reproduced the peculiar mix of synchrony and asynchrony in computer simulations of their own and explored the conditions under which it arises. Strogatz dubbed it the “chimera” state after a mythological fire-breathing monster made of incongruous parts. (Months earlier, Strogatz had written a popular book called Sync, about the pervasiveness of global synchronization.)

Two independent teams realized this chimera state in the lab in 2012, working in different physical systems, and more experiments have seen it since. Many researchers suspect chimeras arise naturally. The brain itself seems to be a complicated kind of chimera, in that it simultaneously sustains both synchronous and asynchronous firing of neurons. Last year, researchers found qualitative similarities between the destabilization of chimera states and epileptic seizures. “We believe that further detailed studies may open new therapeutic methods for promoting seizure prediction and termination,” said co-author Iryna Omelchenko of the University of Berlin.

But the chimera state is still not fully understood. Kuramoto worked out the math verifying that the state is self-consistent, and therefore possible, but that doesn’t explain why it arises. Strogatz and Abrams further developed the math, but other researchers want “a more seat-of-the-pants, physical explanation,” Strogatz said, adding, “I think it’s fair to say that we haven’t really hit the nail on the head yet” about why the chimera state occurs.

Good Vibrations

The discovery of chimeras ushered in a new era in sync science, revealing the conceivably countless exotic forms that synchronization can take. Now, theorists are working to pin down the rules for when and why the different patterns occur. These researchers have bold hopes of learning how to predict and control synchronization in many real-world contexts.

Motter and his team are finding rules about how to stabilize the synchronization of power grids and more stably integrate the U.S. grid with intermittent energy sources like solar and wind. Other researchers are looking for ways of nudging systems between different synchronous states, which could be useful for correcting irregular heartbeats. Novel forms of sync could have applications in encryption. Scientists speculate that brain function and even consciousness can be understood as a complicated and delicate balance of synchrony and asynchrony.

“There’s a lot of new vibrancy to thinking about sync,” said Raissa D’Souza, a professor of computer science and mechanical engineering at University of California, Davis. “We’re gaining the tools to look at these exotic, intricate patterns beyond just simple, full synchronization or regions of synchronization and regions of randomness.”

Many of the new synchronization patterns arise in networks of oscillators, which have specific sets of connections, rather than all being coupled to one another, as assumed in the original Kuramoto model. Networks are better models of many real-world systems, like brains and the internet.

In a seminal paper in 2014, Louis Pecora of the United States Naval Research Laboratory and his co-authors put the pieces together about how to understand synchronization in networks. Building on previous work, they showed that networks break up into “clusters” of oscillators that synchronize. A special case of cluster sync is “remote synchronization,” in which oscillators that are not directly linked nonetheless sync up, forming a cluster, while the oscillators in between them behave differently, typically syncing up with another cluster. Remote synchronization jibes with findings about real-world networks, such as social networks. “Anecdotally it’s not your friend who influences your behavior so much as your friend’s friend,” D’Souza said.

In 2017, Motter’s group discovered that oscillators can remotely synchronize even when the oscillators between them are drifting incoherently. This scenario “breeds remote synchronization with chimera states,” he said. He and his colleagues hypothesize that this state could be relevant to neuronal information processing, since synchronous firing sometimes spans large distances in the brain. The state might also suggest new forms of secure communication and encryption.

Then there’s chaotic synchronization, where oscillators that are individually unpredictable nonetheless sync up and evolve together.

As theorists explore the math underpinning these exotic states, experimentalists have been devising new and better platforms for studying them. “Everyone prefers their own system,” said Matthew Matheny of the California Institute of Technology. In a paper in Science last month, Matheny, D’Souza, Michael Roukes and 12 co-authors reported a menagerie of new synchronous states in a network of “nanoelectromechanical oscillators,” or NEMs — essentially miniature electric drumheads, in this case. The researchers studied a ring of eight NEMs, where each one’s vibrations send electrical impulses to its nearest neighbors in the ring. Despite the simplicity of this eight-oscillator system, “we started seeing a lot of crazy things,” Matheny said.

The researchers documented 16 synchronous states that the system fell into under different initial settings, though many more, rare states might be possible. In many cases, NEMs decoupled from their nearest neighbors and remotely synchronized, vibrating in phase with tiny drumheads elsewhere in the ring. For example, in one pattern, two nearest neighbors oscillated together, but the next pair adopted a different phase; the third pair synced up with the first and the fourth pair with the second. They also found chimeralike states (though it’s hard to prove that such a small system is a true chimera).

NEMs are more complicated than simple Kuramoto oscillators in that the frequency at which they oscillate affects their amplitude (roughly, their loudness). This inherent, self-referential “nonlinearity” of each NEM gives rise to complex mathematical relationships between them. For instance, the phase of one can affect the amplitude of its neighbor, which affects the phase of its next-nearest neighbor. The ring of NEMs serves as “a proxy for other things that are out in the wild,” said Strogatz. When you include a second variable, like amplitude variations, “that opens up a new zoo of phenomena.”

Roukes, who is a professor of physics, applied physics and biological engineering at Caltech, is most interested in what the ring of NEMs suggests about huge networks like the brain. “This is very, very primordial compared to the complexity of the brain,” he said. “If we already see this explosion in complexity, then it seems feasible to me that a network of 200 billion nodes and 2,000 trillion [connections] would have enough complexity to sustain consciousness.”

Broken Symmetries

In the quest to understand and control the way things sync up, scientists are searching for the mathematical rules dictating when different synchronization patterns occur. That major research effort is unfinished, but it’s already clear that synchronization is a direct manifestation of symmetry — and the way it breaks.

The link between synchronization and symmetry was first solidified by Pecora and co-authors in their 2014 paper on cluster synchronization. The scientists mapped the different synchronized clusters that can form in a network of oscillators to that network’s symmetries. In this context, symmetries refer to the ways a network’s oscillators can be swapped without changing the network, just as a square can be rotated 90 degrees or reflected horizontally, vertically or diagonally without changing its appearance.

D’Souza, Matheny and their colleagues applied the same potent formalism in their recent studies with NEMs. Roughly speaking, the ring of eight NEMs has the symmetries of an octagon. But as the eight tiny drums vibrate and the system evolves, some of these symmetries spontaneously break; the NEMs divide into synchronous clusters that correspond to subgroups of the “symmetry group” called D8, which specifies all the ways you can rotate and reflect an octagon that leave it unchanged. When the NEMs sync up with their next-nearest neighbors, for example, alternating their pattern around the ring, D8 reduces to the subgroup D4. This means the network of NEMs can be rotated by two positions or reflected across two axes without changing the pattern.

Even chimeras can be described in the language of clusters and symmetry subgroups. “The synchronized part is one big synchronized cluster, and the desynchronized part is a bunch of single clusters,” said Joe Hart, an experimentalist at the Naval Research Lab who collaborates with Pecora and Motter.

Synchronization seems to spring from symmetry, and yet scientists have also discovered that asymmetry helps stabilize synchronous states. “It is a little bit paradoxical,” Hart admitted. In February, Motter, Hart, Raj Roy of the University of Maryland and Yuanzhao Zhang of Northwestern reported in Physical Review Letters that introducing an asymmetry into a cluster actually strengthens its synchrony. For example, making the coupling between two oscillators in the cluster unidirectional instead of mutual not only doesn’t disturb the cluster’s synchrony, it actually makes its state more robust to noise and perturbations from elsewhere in the network.

These findings about asymmetry hold in experiments with artificial power grids. At the American Physical Society meeting in Boston last month, Motter presented unpublished results suggesting that “generators can more easily oscillate at the exact same frequency, as desired, if their parameters are suitably different,” as he put it. He thinks nature’s penchant for asymmetry will make it easier to stably sync up diverse energy supplies.

“A variety of tasks can be achieved by a suitable combination of synchrony and asynchrony,” Kuramoto observed in an email. “Without a doubt, the processes of biological evolution must have developed this highly useful mechanism. I expect man-made systems will also become much more functionally flexible by introducing similar mechanisms.”

Original story reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent publication of the Simons Foundation, whose mission is to enhance public understanding of science by covering research developments and trends in mathematics and the physical and life sciences.

More Great WIRED Stories

0 notes

Text

The Math of How Crickets, Starlings and Neurons Sync Up

New Post has been published on http://croopdiseno.com/the-math-of-how-crickets-starlings-and-neurons-sync-up/

The Math of How Crickets, Starlings and Neurons Sync Up

When the incoherent claps of a crowd suddenly become a pulse, as everyone starts clapping in unison, who decided? Not you; not anyone. Crickets sing in synchrony; metronomes placed side by side sway into lockstep; some fireflies blink together in the dark. All across the United States, the power grid operates at 60 hertz, its innumerable tributaries of alternating current synchronizing of their own accord. Indeed, we live because of synchronization. Neurons in our brains fire in synchronous patterns to operate our bodies and minds, and pacemaker cells in our hearts sync up to generate the beat.

Quanta Magazine

About

Original story reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent publication of the Simons Foundation, whose mission is to enhance public understanding of science by covering research developments and trends in mathematics and the physical and life sciences.

Objects with rhythms naturally synchronize. Yet the phenomenon went entirely undocumented until 1665, when the Dutch physicist and inventor Christiaan Huygens spent a few days sick in bed. A pair of new pendulum clocks—a kind of timekeeping device that Huygens invented—hung side by side on the wall. Huygens noticed that the pendulums swung exactly in unison, always lurching toward each other and then away. Perhaps pressure from the air was synchronizing their swings? He conducted various experiments. Standing a table upright between the clocks had no effect on their synchronization, for instance. But when he rehung the clocks far apart or at right angles to each other, they soon fell out of phase. Huygens eventually inferred that the clocks’ “sympathy,” as he called it, resulted from the kicks that their swings gave each other through the wall.

When the left pendulum swings left, it kicks the wall and the other pendulum rightward, and vice versa. The clocks kick each other around until they and the wall attain their most stable, relaxed state. For the pendulums, the most stable behavior is to move in opposite directions, so that each pushes the other in the direction it’s already going, the way you push a child on a swing. And this is also easiest for the wall; it no longer moves at all, because the pendulums are giving it equal and opposite kicks. Once in this self-reinforcing, synchronous state, there’s no reason for the system to deviate. Many systems synchronize for similar reasons, with kicks replaced by other forms of influence.

Christiaan Huygens’ sketch of an experiment with a pair of pendulum clocks (top), and his attempt to understand why they synchronize (bottom). “B has gone again through the position BD when A is at AG, whereby the suspension A is drawn to the right, and therefore the vibration of pendulum A is being accelerated,” he wrote. “B is again in BK when A has been returned to position AF, whereby the suspension of B is drawn to the left, and therefore the vibration of pendulum B slows down. And so, when the vibration of pendulum B is steadily slowing down, and A is being accelerated, it is necessary that … they should move together in opposite beats….”

Reproduced from Oeuvres complètes de Christiaan Huygens (1888); Huygens’ passage from Synchronization: A Universal Concept in Nonlinear Sciences (2002)

Another Dutchman, Engelbert Kaempfer, traveled to Thailand in 1690 and observed the local fireflies flashing simultaneously “with the utmost regularity and exactness.” Two centuries later, the English physicist John William Strutt (better known as Lord Rayleigh) noticed that standing two organ pipes side by side can “cause the pipes to speak in absolute unison, in spite of inevitable small differences.” Radio engineers in the 1920s discovered that wiring together electrical generators with different frequencies forced them to vibrate with a common frequency—the principle behind radio communication systems.

It wasn’t until 1967 that the pulsating chirps of crickets inspired the American theoretical biologist Art Winfree to propose a mathematical model of synchronization. Winfree’s equation was too difficult to solve, but in 1974, a Japanese physicist named Yoshiki Kuramoto saw how to simplify the math. Kuramoto’s model described a population of oscillators (things with rhythms, like metronomes and heartbeats) and showed why coupled oscillators spontaneously synchronize.

Kuramoto, then 34, had little prior experience in nonlinear dynamics, the study of the feedback loops that tangle together variables in the world. When he showed his model to experts in the discipline, they failed to grasp its significance. Discouraged, he set the work aside.

Five years later, Winfree came across a précis of a talk Kuramoto had given about his model and realized that it offered a revolutionary new understanding of a subtle phenomenon that pervades the world. Kuramoto’s math has proved versatile and extendable enough to account for synchronization in clusters of neurons, fireflies, pacemaker cells, starlings in flight, reacting chemicals, alternating currents and myriad other real-world populations of coupled “oscillators.”

“I didn’t imagine at all that my model would have a wide applicability,” said Kuramoto, now 78, by email.

But, as ubiquitous as Kuramoto’s model became, any illusions physicists had of understanding synchronization shattered in 2001. Once again, Kuramoto was at the center of the action.

Different Strokes

In Kuramoto’s original model, an oscillator can be pictured as an arrow that rotates in a circle at some natural frequency. (If it’s a firefly, it might flash every time the arrow points up.) When a pair of arrows are coupled, the strength of their mutual influence depends on the sine of the angle between their pointing directions. The bigger this angle, the bigger the sine, and therefore the stronger their mutual influence. Only when the arrows point in parallel directions, and rotate together, do they stop pulling on each other. Thus, the arrows will drift until they find this state of synchrony. Even oscillators that have different natural frequencies, when coupled, reach a compromise and oscillate in tandem.

But that basic picture only explains the onset of global synchronization, where a population of oscillators all do the same thing. As well as being the simplest kind of sync, “there are plenty of examples of global synchronization; that’s why people paid so much attention to that,” said Adilson Motter, a physicist at Northwestern University in Chicago, and a leading sync scientist. “But in 2001, Kuramoto discovered something very different. And that’s where the story of different states starts.”

Yoshiki Kuramoto, a professor of physics at Kyoto University, developed the famous Kuramoto model of synchronization in the 1970s and co-discovered the chimera state in 2001, again revolutionizing the understanding of sync.

Tomoaki Sukezane

It was Kuramoto’s Mongolian post-doc, Dorjsuren Battogtokh, who first noticed a new kind of synchronous behavior in a computer-simulated population of coupled oscillators. The identical oscillators, which were all identically coupled to their neighbors, had somehow split into two factions: Some oscillated in sync, while the rest drifted incoherently.

Kuramoto presented his and Battogtokh’s discovery at a 2001 meeting in Bristol, but the result didn’t register in the community until Steven Strogatz, a mathematician at Cornell University, came across it in the conference proceedings two years later. “When I came to understand what I was seeing in the graphics, I didn’t really believe it,” Strogatz said.

“What was so weird,” he explained, “was that the universe looks the same from every place” in the system. And yet the oscillators responded differently to identical conditions, some ganging together while the rest went their own way, as if not coupled to anything at all. The symmetry of the system “was broken,” Strogatz said, in a way that “had never been seen before.”

Strogatz and his graduate student Daniel Abrams, who now studies synchronization as a professor at Northwestern, reproduced the peculiar mix of synchrony and asynchrony in computer simulations of their own and explored the conditions under which it arises. Strogatz dubbed it the “chimera” state after a mythological fire-breathing monster made of incongruous parts. (Months earlier, Strogatz had written a popular book called Sync, about the pervasiveness of global synchronization.)

Two independent teams realized this chimera state in the lab in 2012, working in different physical systems, and more experiments have seen it since. Many researchers suspect chimeras arise naturally. The brain itself seems to be a complicated kind of chimera, in that it simultaneously sustains both synchronous and asynchronous firing of neurons. Last year, researchers found qualitative similarities between the destabilization of chimera states and epileptic seizures. “We believe that further detailed studies may open new therapeutic methods for promoting seizure prediction and termination,” said co-author Iryna Omelchenko of the University of Berlin.

But the chimera state is still not fully understood. Kuramoto worked out the math verifying that the state is self-consistent, and therefore possible, but that doesn’t explain why it arises. Strogatz and Abrams further developed the math, but other researchers want “a more seat-of-the-pants, physical explanation,” Strogatz said, adding, “I think it’s fair to say that we haven’t really hit the nail on the head yet” about why the chimera state occurs.

Good Vibrations

The discovery of chimeras ushered in a new era in sync science, revealing the conceivably countless exotic forms that synchronization can take. Now, theorists are working to pin down the rules for when and why the different patterns occur. These researchers have bold hopes of learning how to predict and control synchronization in many real-world contexts.

Motter and his team are finding rules about how to stabilize the synchronization of power grids and more stably integrate the U.S. grid with intermittent energy sources like solar and wind. Other researchers are looking for ways of nudging systems between different synchronous states, which could be useful for correcting irregular heartbeats. Novel forms of sync could have applications in encryption. Scientists speculate that brain function and even consciousness can be understood as a complicated and delicate balance of synchrony and asynchrony.

“There’s a lot of new vibrancy to thinking about sync,” said Raissa D’Souza, a professor of computer science and mechanical engineering at University of California, Davis. “We’re gaining the tools to look at these exotic, intricate patterns beyond just simple, full synchronization or regions of synchronization and regions of randomness.”

Many of the new synchronization patterns arise in networks of oscillators, which have specific sets of connections, rather than all being coupled to one another, as assumed in the original Kuramoto model. Networks are better models of many real-world systems, like brains and the internet.

In a seminal paper in 2014, Louis Pecora of the United States Naval Research Laboratory and his co-authors put the pieces together about how to understand synchronization in networks. Building on previous work, they showed that networks break up into “clusters” of oscillators that synchronize. A special case of cluster sync is “remote synchronization,” in which oscillators that are not directly linked nonetheless sync up, forming a cluster, while the oscillators in between them behave differently, typically syncing up with another cluster. Remote synchronization jibes with findings about real-world networks, such as social networks. “Anecdotally it’s not your friend who influences your behavior so much as your friend’s friend,” D’Souza said.

In 2017, Motter’s group discovered that oscillators can remotely synchronize even when the oscillators between them are drifting incoherently. This scenario “breeds remote synchronization with chimera states,” he said. He and his colleagues hypothesize that this state could be relevant to neuronal information processing, since synchronous firing sometimes spans large distances in the brain. The state might also suggest new forms of secure communication and encryption.

Then there’s chaotic synchronization, where oscillators that are individually unpredictable nonetheless sync up and evolve together.

As theorists explore the math underpinning these exotic states, experimentalists have been devising new and better platforms for studying them. “Everyone prefers their own system,” said Matthew Matheny of the California Institute of Technology. In a paper in Science last month, Matheny, D’Souza, Michael Roukes and 12 co-authors reported a menagerie of new synchronous states in a network of “nanoelectromechanical oscillators,” or NEMs — essentially miniature electric drumheads, in this case. The researchers studied a ring of eight NEMs, where each one’s vibrations send electrical impulses to its nearest neighbors in the ring. Despite the simplicity of this eight-oscillator system, “we started seeing a lot of crazy things,” Matheny said.

The researchers documented 16 synchronous states that the system fell into under different initial settings, though many more, rare states might be possible. In many cases, NEMs decoupled from their nearest neighbors and remotely synchronized, vibrating in phase with tiny drumheads elsewhere in the ring. For example, in one pattern, two nearest neighbors oscillated together, but the next pair adopted a different phase; the third pair synced up with the first and the fourth pair with the second. They also found chimeralike states (though it’s hard to prove that such a small system is a true chimera).

NEMs are more complicated than simple Kuramoto oscillators in that the frequency at which they oscillate affects their amplitude (roughly, their loudness). This inherent, self-referential “nonlinearity” of each NEM gives rise to complex mathematical relationships between them. For instance, the phase of one can affect the amplitude of its neighbor, which affects the phase of its next-nearest neighbor. The ring of NEMs serves as “a proxy for other things that are out in the wild,” said Strogatz. When you include a second variable, like amplitude variations, “that opens up a new zoo of phenomena.”

Roukes, who is a professor of physics, applied physics and biological engineering at Caltech, is most interested in what the ring of NEMs suggests about huge networks like the brain. “This is very, very primordial compared to the complexity of the brain,” he said. “If we already see this explosion in complexity, then it seems feasible to me that a network of 200 billion nodes and 2,000 trillion [connections] would have enough complexity to sustain consciousness.”

Broken Symmetries

In the quest to understand and control the way things sync up, scientists are searching for the mathematical rules dictating when different synchronization patterns occur. That major research effort is unfinished, but it’s already clear that synchronization is a direct manifestation of symmetry — and the way it breaks.

The link between synchronization and symmetry was first solidified by Pecora and co-authors in their 2014 paper on cluster synchronization. The scientists mapped the different synchronized clusters that can form in a network of oscillators to that network’s symmetries. In this context, symmetries refer to the ways a network’s oscillators can be swapped without changing the network, just as a square can be rotated 90 degrees or reflected horizontally, vertically or diagonally without changing its appearance.

D’Souza, Matheny and their colleagues applied the same potent formalism in their recent studies with NEMs. Roughly speaking, the ring of eight NEMs has the symmetries of an octagon. But as the eight tiny drums vibrate and the system evolves, some of these symmetries spontaneously break; the NEMs divide into synchronous clusters that correspond to subgroups of the “symmetry group” called D8, which specifies all the ways you can rotate and reflect an octagon that leave it unchanged. When the NEMs sync up with their next-nearest neighbors, for example, alternating their pattern around the ring, D8 reduces to the subgroup D4. This means the network of NEMs can be rotated by two positions or reflected across two axes without changing the pattern.

Even chimeras can be described in the language of clusters and symmetry subgroups. “The synchronized part is one big synchronized cluster, and the desynchronized part is a bunch of single clusters,” said Joe Hart, an experimentalist at the Naval Research Lab who collaborates with Pecora and Motter.

Synchronization seems to spring from symmetry, and yet scientists have also discovered that asymmetry helps stabilize synchronous states. “It is a little bit paradoxical,” Hart admitted. In February, Motter, Hart, Raj Roy of the University of Maryland and Yuanzhao Zhang of Northwestern reported in Physical Review Letters that introducing an asymmetry into a cluster actually strengthens its synchrony. For example, making the coupling between two oscillators in the cluster unidirectional instead of mutual not only doesn’t disturb the cluster’s synchrony, it actually makes its state more robust to noise and perturbations from elsewhere in the network.

These findings about asymmetry hold in experiments with artificial power grids. At the American Physical Society meeting in Boston last month, Motter presented unpublished results suggesting that “generators can more easily oscillate at the exact same frequency, as desired, if their parameters are suitably different,” as he put it. He thinks nature’s penchant for asymmetry will make it easier to stably sync up diverse energy supplies.

“A variety of tasks can be achieved by a suitable combination of synchrony and asynchrony,” Kuramoto observed in an email. “Without a doubt, the processes of biological evolution must have developed this highly useful mechanism. I expect man-made systems will also become much more functionally flexible by introducing similar mechanisms.”

Original story reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent publication of the Simons Foundation, whose mission is to enhance public understanding of science by covering research developments and trends in mathematics and the physical and life sciences.

More Great WIRED Stories

0 notes

Text

The Math of How Crickets, Starlings and Neurons Sync Up

New Post has been published on http://team77.com/the-math-of-how-crickets-starlings-and-neurons-sync-up/

The Math of How Crickets, Starlings and Neurons Sync Up

When the incoherent claps of a crowd suddenly become a pulse, as everyone starts clapping in unison, who decided? Not you; not anyone. Crickets sing in synchrony; metronomes placed side by side sway into lockstep; some fireflies blink together in the dark. All across the United States, the power grid operates at 60 hertz, its innumerable tributaries of alternating current synchronizing of their own accord. Indeed, we live because of synchronization. Neurons in our brains fire in synchronous patterns to operate our bodies and minds, and pacemaker cells in our hearts sync up to generate the beat.

Quanta Magazine

About

Original story reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent publication of the Simons Foundation, whose mission is to enhance public understanding of science by covering research developments and trends in mathematics and the physical and life sciences.

Objects with rhythms naturally synchronize. Yet the phenomenon went entirely undocumented until 1665, when the Dutch physicist and inventor Christiaan Huygens spent a few days sick in bed. A pair of new pendulum clocks—a kind of timekeeping device that Huygens invented—hung side by side on the wall. Huygens noticed that the pendulums swung exactly in unison, always lurching toward each other and then away. Perhaps pressure from the air was synchronizing their swings? He conducted various experiments. Standing a table upright between the clocks had no effect on their synchronization, for instance. But when he rehung the clocks far apart or at right angles to each other, they soon fell out of phase. Huygens eventually inferred that the clocks’ “sympathy,” as he called it, resulted from the kicks that their swings gave each other through the wall.

When the left pendulum swings left, it kicks the wall and the other pendulum rightward, and vice versa. The clocks kick each other around until they and the wall attain their most stable, relaxed state. For the pendulums, the most stable behavior is to move in opposite directions, so that each pushes the other in the direction it’s already going, the way you push a child on a swing. And this is also easiest for the wall; it no longer moves at all, because the pendulums are giving it equal and opposite kicks. Once in this self-reinforcing, synchronous state, there’s no reason for the system to deviate. Many systems synchronize for similar reasons, with kicks replaced by other forms of influence.