Photo

Colorful Compositions: Mystical Madonna As Seen in Paintings by El Greco

As an artist mainly working during the Catholic Counter Reformation and (Italian and Spanish) Renaissance, El Greco became an artist deeply involved in artworks which contributed to the Catholic faith. Often greatly criticized for his use of hues sometimes called “garrish”, he fell in love with and explored color in his many works. Originally from Crete, the artist trained in Venice, where a concentration on the artistic use of color, called colore, was believed to be superior to the Floriencian focus on form, or disegno. This is especially seen in his works created in Toledo, four of which I’ve chosen to discuss below:

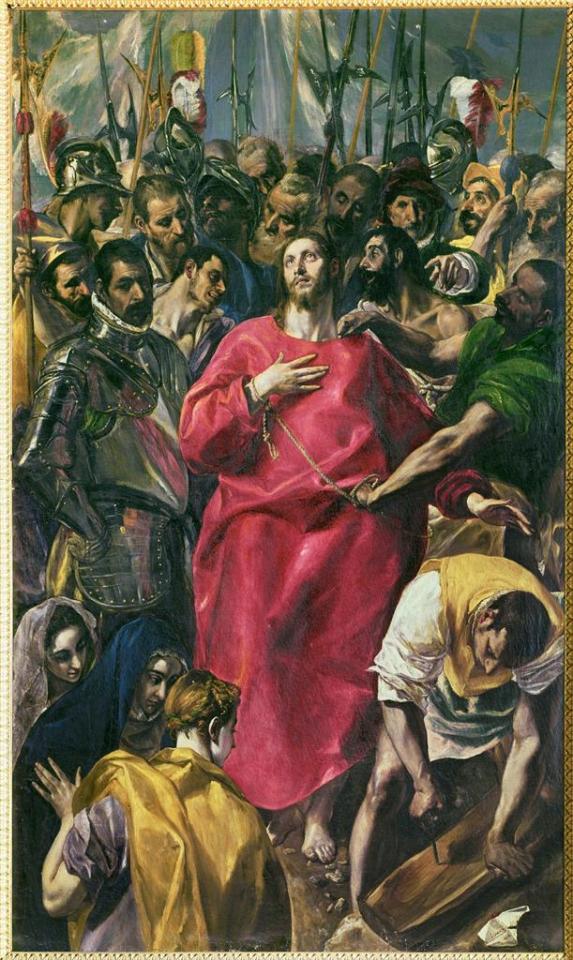

Disrobing of Christ, ca. 1577-79, oil on panel, 55.9 x 31.8 cm.

El Greco produced this work for the sacristy of the cathedral of Toledo, and although it was questioned by art critics of the 16th century, it is today regarded as one of Europe’s greatest masterpieces and one of El Greco’s most significant commissions. The great controversy surrounded the artist’s choice to include the three Mary’s (seen in the lower right-hand corner), as well as the claustrophobic positioning of figures, some placed on a higher level than that of Christ. One may argue that the bold use of red in Christ’s robes sets him apart and distinguishes him from the rest of the figures. Additionally, the Mary’s act as a crucial compositional device in both appealing to the Spanish cult of the Virgin Mary and addressing the clever foreshadowing of Christ’s crucifixion, seen opposite of their concentrated gazes directed towards a figure preparing the cross-shaped wood. However, seeing as how they were not part of the biblical passage attributed to the painting, this artistic choice was highly criticized and led to a legal dispute with the canons, who attempted to devalue and underpay El Greco for his efforts. In the long term, El Greco profited from his artistic choices: copies were constantly being requested from the Cretan old master and his workshop.

Saint Lawrence’s Vision of the Virgin, ca. 1578-1580, oil on canvas, 119 x 102 cm.

This early Toledo painting by El Greco profoundly expresses and embodies both the sense and adoration of color by the artist. With ruddy flesh tones seen in the saint’s hands, the vestment’s gold-and-red brocade, and the vivaciously pastel-like sky blue, Venice’s influence on the Cretan painter is surely evident. Here, St. Lawrence’s figure is clearly cut and contoured, resembling a , statue, a medium El Greco had expertise in just as well. The extensively defined, exquisite robes envelope Saint Lawrence, the patron saint of the Escorial, who had a fairly popular Spanish cult (although nowhere near as many fans and followers as the Virgin.) Here, both of the cults may find solace, as the saint visualizes the divine figures of the Virgin and Child, who are perched on a cloud in the patchy sky. He holds in his right hand (our left) the symbol of his martyrdom, the iron grate upon which he was grilled alive. Both decorative and fantastical, this work was created with the intention of appealing to Phillip II of Spain, for whom he wished to become hired as a court artist. Although these aspirations did not become to be, El Greco’s career reached heights which it may never have grasped under the command of a royal patron.

Madonna and Child with Saint Martina and Saint Agnes, ca. 1597-99, oil on canvas, 193.4 x 102.9 cm.

Here, the Madonna is the center of attention, as she is perched upon a cloud which acts as a heavenly throne, clothed in robes of a rosy violet and cobalt blue. Peering up at them and the surrounding angels are the two female saints, Martina and Agnes. The former is well placed in the painting, seeing as how she is the female counterpart of Saint Martin, the patron saint of the chapel’s founder. Martina places one hand on the head of a lion, which matches the gold of her robes of azure and sunflower-blue, and the other hand faces up to the Virgin as a sign of devotion. The latter is identified by her characteristic symbol of the lamb, which she rests one hand on, laying the other on her heart in compassionate loyalty. She is cloaked in a saturated berry and tangerine, which work in harmony with her animal attribution and the clouds permeating the composition. Saints Martina and Agnes complement the Virgin, as they are the “virgin martyrs” of the Catholic faith.

Pentecost, ca. 1600, oil on canvas, 275 x 127 cm.

There has been much controversy surrounding the intended setting for this painting by El Greco. It is suspected to have been grouped with five other canvases decorating the Church of the College of Dona Maria de Aragon in Madrid. The Pentecost is alternatively referred to as the Descent of the Holy Spirit, and represents a biblical scene from the New Testament. In the scripture, the Feast of the Pentecost, which followed Christ’s Ascension, experienced a divine miracle among a vast gathering of followers, including the Virgin Mary, who is placed centrally in the composition. A bellowing sound of wind erupted among the crowd as they were filled with the Holy Ghost, whose Spirit caused them to speak foreign tongues. This is visualized in the form of figures and apostles cramped into a semicircular formation, with some gazing up towards the Holy Spirit shining brightly above them, and others gazing at the lovely Madonna, again robed in in violet and cobalt. Others contrast her with hues of silver, forest green, and a golden yellow. A couple of figures below them mimic their gestures of faith, seen in their hands either clasped together or raised upward in devotion, but do so more dramatically. Falling to the knees with the utter force of the Holy Spirit, they bring some action to the otherwise seemingly still composition.

Commonalities in the compositions include their inclusion of the Virgin Mary, or the Madonna, textured costume(s), clouds, and religious themes. It is important to note that the Virgin is depicted differently throughout each of these four works, either in dimension, attire, of physiognomy. El Greco earns the title of an “old master” with his ability to communicate texture with highlights, shadows, and color choices. Additionally, Christ is in each of the paintings excluding the Pentecost, which marks a scene following his crucifixion. The overarching rendition of clouds offsets the courageous chroma El Greco paints with. Mary, as the mother of Christ, is crucial to ecclesially themed art, and especially considering El Greco’s audience in Spain, which venerated the Virgin more than any other biblical figure.

1 note

·

View note