Text

Blog No. 13

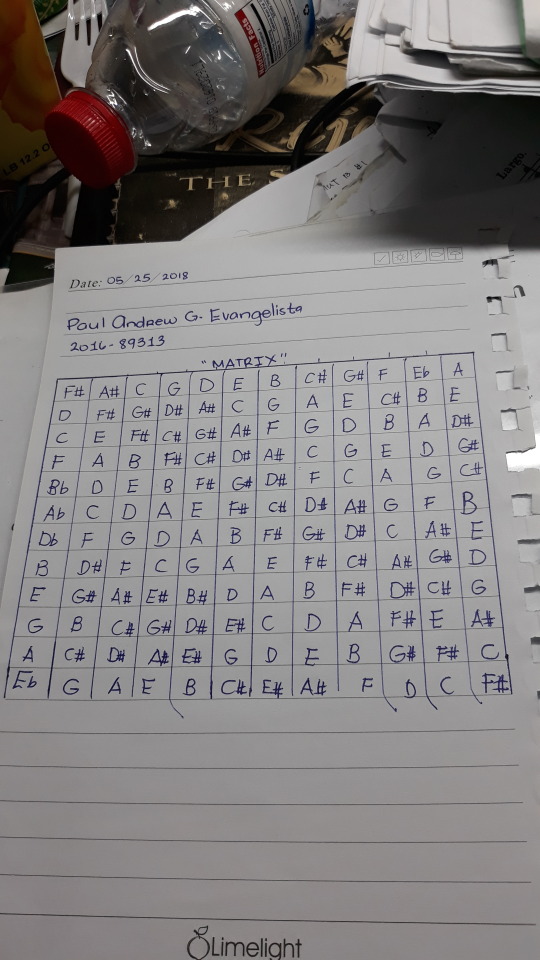

My Matrix Preparation!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No. 12

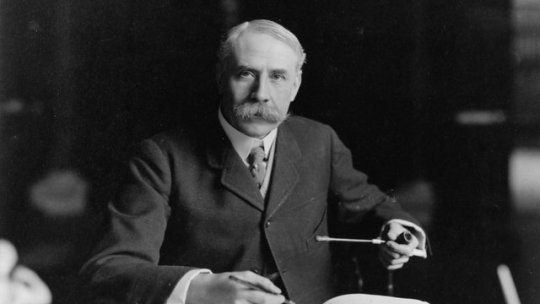

“Salut D'Amour.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Apr. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salut_d'Amour. This time, I had a chance to team up with my classmate Mareal Tumanda, who, like me, also plays the violin. We kind of had a lecture performance on Elgar’s Serenade for Strings, (Large/Ensemble Work) and then, I played “Salut d’Amour” for solo violin, which is still Elgar’s work.

Serenade for Strings (String Orchestra) in E Minor, Op. 20

Performers: (Violin 1) Paul Andrew Evangelista, (Violin 2) Mareal Tumanda, (Viola) Paul Anthony Evangelista- backup performer, (Cello) ‘None’

*Unfortunately, we were not able to find a cello player for the piece. :(

Elgar’s “Serenade for Strings” is a very sublime piece for strings, as the composer described it; “real stringy”.The central Larghetto, (2nd Mvt.) generally accepted as containing the work’s finest and most mature writing. The leap of a seventh followed by a descending figuration in his melody makes it so moving and lovely. <3

youtube

Description by Rovi Staff

Nothing disturbs the graceful amiability of this early work, begun a year before Elgar's marriage in 1889. These "little tunes," as the composer called them, are about as far as one can get from the patriotic fervor of the Pomp and Circumstance marches and the emotional intensity of the larger orchestral works.

All three movements, Allegro piacevole, Larghetto and Allegretto, are enchanting: the first liltingly rhythmic, the second a meditation of serene beauty on a melody similar to that of the Lento movement in the Symphony No. 1, the third a genial reworking of first-movement themes.

The opening movement, in 6/8 time, is based around an opening theme which is suffused with the feel of English ballad; perhaps some snatch of West-Country melody caught the young composer's ear and worked its way into his creative process. It weaves in and out of minor and major before yielding to the no less serene second theme, bearing Elgar's trademark interval of a seventh leap. This same thumbprint figure can be found in the sensitive following movement, in which there is a constant unfolding of melody rather than contrasting themes. A Tristan-like turn, as well as a phrase which seems to be a quotation from that opera (Elgar was an unashamed admirer of Wagner's music), are worked up to a crest which subsides; overall, though, the music is purged of excessive chromaticism, and any Wagnerisms used in a very different and sensitive context. The closing movement uses a sunny and winsome theme also in 6/8 and returns to the seventh leap of the opening movement, the theme in its final resolution bearing a curious resemblance to the trio of the last Pomp and Circumstance nearly 40 years later. Coincidental? Perhaps, but also indicative that nothing is incongruous within one's own frame of reference.

Elgar, himself a violinist, was sensitive to the coloration of the string orchestra, and his touch does not falter throughout a work which he described as being "real stringy." There is no straining after effect and no obvious personal or pictorial associations -- all is pure music as well as pure poetry. Yet anyone who knows the English countryside around Hereford where Elgar lived can hardly fail, especially in the second movement, to be reminded of that peaceful, solitary landscape.

The composer made an arrangement of the Serenade for piano duet, though it is now difficult to think of it other than in its original form.

Salut d’Amour “Liebesgruss”, Op. 12

A musical work for violin and piano composed by Edward Elgar in 1888. Elgar finished this piece when he was romantically in loved with Caroline Alice Roberts. On their engagement she had already presented him with a poem "The Wind at Dawn" which he set to music and, when he returned home to London on 22 September from a holiday at the house of his friend Dr. Charles Buck in Settle, he gave her Salut d'Amour as an engagement present. The dedication was in French: "à Carice". "Carice" was a combination of his wife's names Caroline Alice, and was the name to be given to their daughter born two years later. It was not published by Schott & Co., a German publisher, with offices in Mainz, London, Paris and Brussels, until a year later, and the first editions were for violin and piano, piano solo, cello and piano, and for small orchestra. Few copies were sold until Schott changed the title to "Salut d'Amour" with Liebesgruss as a sub-title, and the composer's name as 'Ed. Elgar'. The French title, Elgar realised, would help the work to be sold not only in France but in other European countries. The first public performance was of the orchestral version, at a Crystal Palace concert on 11 November 1889, conducted by August Manns. The first recording of that version was made in 1915 for The Gramophone Company with an orchestra conducted by the composer. As a violin-and-piano piece Salut d'Amour had been recorded for The Gramophone & Typewriter Ltd (predecessor to The Gramophone Company) as early as 1901 by Jacques Jacobs, leader/director of the Trocadero Restaurant orchestra. Auguste van Biene recorded a cello transcription in 1907.

A Thrilling, Lovely Experience!!! <3

I was really excited to perform these two works by Elgar, yet at the same time nervous. Especially, because I thought that Mareal would not be able to come on class that day. Thank God! Finally, she came in, then I took a deep breath and stopped being worried.

While discussing Elgar’s “Serenade for Strings” I felt a bit nervous because we really didn’t discussed what measures we’ll be playing in the music but rather just practiced it on our own so I just told them to look at my cues/cut-offs so we would end together, but they didn’t. Oh well, we’re just humans... sometimes we forget. At one point, I felt that everything that I thought in my mind doesn’t really come out on my mouth, so some of the details that I want to say and elaborate just passed through my mind.

In playing Elgar’s Salut d’Amour, I was moved with passion by the music. I felt love and joy after the performance. I was fortunate, at the same time happy performing the piece in front of my MuL15 classmates, with Ma’am Krina as our professor.

Disclaimer: Pardon me for my performance here... It has a lot of tempo and intonation problems... huhuhuhu Thank you. <3

youtube

Sources:

“Serenade, for Strings in E Minor,... | Details.” AllMusic, www.allmusic.com/composition/serenade-for-strings-in-e-minor-op-20-mc0002399377.

“Salut D'Amour.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Apr. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salut_d'Amour.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No. 11

Claude Debussy’s Claire De Lune Description:

Claire De Lune is one of the most well-known pieces of Claude Debussy’s piano works. Claire De Lune means “moonlight” and it’s not even a standalone piece. This small piece is one part of a bigger piece called Suite bergamasque.

youtube

Analysis: Written in ABA form, otherwise known as ternary form or three-part form. The first section cannot be distinguished by its rhythm but rather its sound and spaciousness. The second section is more punctuated in terms of impulse, and the piece rolls into spacious lyricism until the return of the not exactly identical first section where an actual perfect cadence will finally end the mystique of this piece.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No. 10

Wagnerian Music Drama

youtube

Musical Analysis

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No. 9

Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini’s Aria (Analysis)

Gioachino Antonio Rossini

(February 29, 1792—November 13, 1868)

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) was an Italian composer who wrote 39 operas as well as sacred music, chamber music, songs, and some instrumental and piano pieces.

Life and Music

Having produced a whirlwind series of 38 operas, following the premiere of William Tell in August 1829, and with close on 40 years of life still remaining, he laid down his operatic pen for ever. Perhaps Rossini had finally had enough, as he was once reputed to have remarked: "How wonderful opera would be if there were no singers!"

Rossini was born in Pesaro in 1793, the son of a town trumpeter-cum-inspector of slaughterhouses, ‘Guiseppe Rossini’ whose questionable political sympathies once resulted in a short jail sentence. The family was otherwise constantly on the move, Rossini's mother appearing as a principal singer in a series of comic opera productions, while the budding young composer learned his craft, based in Bologna.

He composed his first opera, Demetrio e Polibio, while still a student at the Liceo Musicale in Bologna, where his love of Mozart led to his being nicknamed, "the German". Such was its success that it led to a series of operatic ventures which initially culminated in the Barber of Seville. When Donizetti heard that Rossini had composed it in a matter of just three weeks, he remarked sardonically: "Rossini always was a lazy fellow."

Rossini's stage output culminated in the premiere of William Tell in Paris in 1829, after which he virtually stopped composing, save for a few songs, piano pieces and two famous large-scale choral works - the Stabat Mater and the Petite Messe Solennelle .

Rossini died at his villa in Passy on 13 November 1868 following a short illness. Having initially been buried in Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, his remains were subsequently moved to Santa Croce in Florence in 1887.

Did you know?

For Rossini's 70th birthday celebrations in 1862, a number of his friends clubbed together in order to have a statue built in his honour. His reaction was typically boisterous: "Why not give the money to me and I'll stand on the pedestal myself!"

Figaro's “Largo Al Factotum,” From 'The Barber of Seville'

youtube

"The Barber of Seville" (Italian: Il barbiere di Siviglia) is a comedic opera by Giachino Rossini. It's based on the first play of of "Le Barbier de Seville," the three-part story of Figaro written by French playwright Pierre Beaumarchais.

"Largo al Factorum," Figaro's opening aria in the opera's first act, is considered one of the most challenging operas for a baritone to perform, due to its brisk time signature and convoluted rhyme structure.

Modern audiences may recognize "Largo al factotum" as a staple of the "Looney Tunes" cartoons.

History of 'The Barber of Seville'

The opera premiered at the Teatro Argentina in Rome in 1816. Now considered a masterpiece of musical comedy, "The Barber of Seville" had a difficult first performance, but quickly grew in popularity.

Figaro's Opening Aria 'Largo al Factorum'

In the first act, the audience meets the flamboyant Figaro who introduces himself as the city's top quality factotum, or handyman. Figaro is quite assured of his abilities and describes his popularity and his many talents. He's a jack of all trades. He loves his life, saying that and a more noble life cannot be found.

Italian Lyrics

Largo al factotum della citta.

Presto a bottega che l'alba e gia.

Ah, che bel vivere, che bel piacere

per un barbiere di qualita!

Ah, bravo Figaro!

Bravo, bravissimo!

Fortunatissimo per verita!

Pronto a far tutto,

la notte e il giorno

sempre d'intorno in giro sta.

Miglior cuccagna per un barbiere,

vita piu nobile, no, non si da.

Rasori e pettini

lancette e forbici,

al mio comando

tutto qui sta.

V'e la risorsa,

poi, de mestiere

colla donnetta... col cavaliere...

Tutti mi chiedono, tutti mi vogliono,

donne, ragazzi, vecchi, fanciulle:

Qua la parruca... Presto la barba...

Qua la sanguigna...

Presto il biglietto...

Qua la parruca, presto la barba,

Presto il biglietto, ehi!

Figaro! Figaro! Figaro!, ecc.

Ahime, che furia!

Ahime, che folla!

Uno alla volta, per carita!

Figaro! Son qua.

Ehi, Figaro! Son qua.

Figaro qua, Figaro la,

Figaro su, Figaro giu,

Pronto prontissimo son come il fumine:

sono il factotum della citta.

Ah, bravo Figaro! Bravo, bravissimo;

a te fortuna non manchera.

English Translation

Handyman of the city.

Early in the workshop I arrive at dawn.

Ah, what a life, what a pleasure

For a barber of quality!

Ah, bravo Figaro!

Bravo, very good!

I am the luckiest, it's the truth!

Ready for anything,

night and day

I'm always on the move.

Cushier fate for a barber,

A more noble life cannot be found.

Razors and combs

Lancets and scissors,

at my command

everything is here.

Here are the extra tools

then, for business

With the ladies... with the gentlemen...

Everyone asks me, everyone wants me,

women, children, old people, young ones:

Here are the wigs... A quick shave of the beard...

Here are the leeches for bleeding...

The note...

Here are the wigs, a quick shave soon,

The note, hey!

Figaro! Figaro! Figaro!, Etc..

Alas, what frenzy!

Alas, what a crowd!

One at a time, for goodness sake!

Figaro! I'm here.

Hey, Figaro! I'm here.

Figaro here, Figaro there,

Figaro up, Figaro down,

Swifter and swifter I'm like a spark:

I'm the handyman of the city.

Ah, bravo Figaro! Bravo, very good;

Fortunately for you I will not fail.

Musical Analysis:

Written in ABA form, also know as a ternary form or a song form. The flamboyant opening of the orchestra gave preparation to the robust melody of the baritone solo. The bass section opens the music with a masculine one-note pluck, suggesting a dominant chord then suddenly, the orchestra comes in, full blast, with a lot scalar passages, leaps of an octave, and grace notes. The 1st section revolves in its home key, C major, sometimes sitting to its dominant key, (G) then transitions to Eb major in the 2nd section by using ascending half step patterns from the note G up to Eb in a syllable ‘Na’. (G-F#-G, Ab-G-Ab-, A-G#-A, Bb-A-Bb, B-A#-B, CBC, D-C#-D---Eb) It goes to its relative minor, (C) then eventually went back to tonic.

Artist Biography

Gaetano Donizetti was among the most important composers of bel canto opera in both Italian and French in the first half of the nineteenth Century. Many of Donizetti's more than 60 operas are still part of the modern repertoire and continue to challenge singers for their musical and technical demands. Donizetti stands stylistically between Rossini and Verdi; his scenes are usually more expanded in structure than those of Rossini, but he never blurred the lines between set pieces and recitative as Verdidid in his middle-period and late works. Often compared to his contemporary, Bellini, Donizetti produced a wider variety of operas and showed a greater stylistic flexibility, even if he never quite achieved the sheer beauty of Bellini's greatest works.

Donizetti was educated in Bergamo, the town of his birth, studying with the opera composer Simon Mayr from 1806 to 1814. His youthful works include chamber operas, religious works, and some chamber music. Donizetti's first opera of note was La Zingara, which was premiered in Naples in 1822. He continued to work in Naples throughout the 1820's and 1830's, where he was active as both a conductor and composer.

In 1830, Donizetti finally achieved international fame with his opera Anna Bolena; notable for its expressive music and more extended scenes, it established Donizetti as one of the leading contemporary opera composers. The comic opera L'elisir d'amore (1832) and the tragic Lucrezia Borgia (1833) came shortly after. Donizetti's next work was Maria Stuarda, followed the same year by Lucia di Lammermoor (1835), which became an internationally recognized masterpiece. The Elizabethan tragedy Roberto Devereux (1837) completed his trilogy of operas that chronicle the English court from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I.

Donizetti's operas from the late 1830s were unable to match the success of Lucia, and when Donizetti was passed over for the directorship of the Naples Conservatory in 1840, he moved to Paris. There he composed the opera comique La fille du Régiment (1840), which was celebrated immediately for its charm and virtuosity. Later that year he completed La favorite (1840), another major contribution to the French repertoire. In 1842 Donizetti was appointed Kapellmeister of the Austrian court in Vienna, but retained his association with Paris.

Among Donizetti's last operas are Maria di Rohan (1843), an important historic opera, and his French tragedy Dom Sébastian (1843). Caterina Cornaro (1843) is also one of his finest works for its strong dramatic content. These late operas, although rarely performed, are serious works that set the standard for Verdi.

- Steven Coburn

“Una Furtiva Lagrima” From Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore

youtube

Italian Text of 'Una Furtiva Lagrima'

Una furtiva lagrima

negli occhi suoi spuntò:

Quelle festose giovani

invidiar sembrò.

Che più cercando io vo?

Che più cercando io vo?

M'ama! Sì, m'ama, lo vedo. Lo vedo.

Un solo instante i palpiti

del suo bel cor sentir!

I miei sospir, confondere

per poco a' suoi sospir!

I palpiti, i palpiti sentir,

confondere i miei coi suoi sospir...

Cielo! Si può morir!

Di più non chiedo, non chiedo.

Ah, cielo! Si può! Si, può morir!

Di più non chiedo, non chiedo.

Si può morire! Si può morir d'amor.

English Translation of 'Una Furtiva Lagrima'

A single secret tear

from her eye did spring:

as if she envied all the youths

that laughingly passed her by.

What more searching need I do?

What more searching need I do?

She loves me! Yes, she loves me, I see it. I see it.

For just an instant the beating

of her beautiful heart I could feel!

As if my sighs were hers,

and her sighs were mine!

The beating, the beating of her heart I could feel,

to merge my sighs with hers...

Heavens! Yes, I could die!

I could ask for nothing more, nothing more.

Oh, heavens! Yes, I could, I could die!

I could ask for nothing more, nothing more.

Yes, I could die! Yes, I could die of love.

L’elisir d’amore, (Italian: “The Elixir of Love” or “The Love Potion”) comic opera in two acts by the Italian composer Gaetano Donizetti (Italian libretto by Felice Romani, after a French libretto by Eugène Scribe for Daniel-François-Esprit Auber’s Le Philtre, 1831) that premiered in Milanon May 12, 1832.

Main Characters

Nemorino — a good-hearted but penniless waiter

Adina — a wealthy and beautiful bar owner

Belcore — experienced charmer and Nemorino’s rival

Dulcamara — a travelling ‘quack’ (medicine man), who touts a dubious cure-all elixir

Giannetta — Adina’s friend and town gossip

Music

What separates L’Elisir d’Amore from dozens of charming comedies composed around the same time is not only the superiority of its hit numbers, but the overall consistency of its music. It represents the best of the bel canto tradition that reigned in Italian opera in the early 19th century—from funny patter songs to rich ensembles to wrenching melody in the solos, most notably the tenor’s showstopping aria “Una furtiva lagrima” in Act II. Its variations between major and minor keys in the climaxes are one of opera’s savviest depictions of a character’s dawning consciousness.

Setting And Story Summary

The opera is set in a small village in the early 19th century, rural Italy. Some early editions indicate a location in Basque country. The important fact is that it’s a place where everyone knows everyone and where traveling salesmen provide a major form of public entertainment.

Act I

Adina’s farm. Adina is sitting beneath a tree on her farm, reading a book. Her friend Giannetta and other peasants are resting nearby. Nemorino watches Adina from a distance, lamenting that he has nothing but love to offer her (“Quànto è bella, quànto è cara”). The peasants ask Adina to read to them, and she reads them the story of how Tristan won Isolde by drinking a magic love potion.

Sergeant Belcore swaggers in with his troop. Adina laughs at his braggadocio, but when he presses her to marry him, she promises to think it over. She invites the whole troop to her house for some wine, and the peasants return to their work. Nemorino intercepts Adina on her way to the house and awkwardly declares his love for her. She tells him that he is a nice fellow but that she is not inclined to fall in love with anyone.

In the village square, the populace eagerly greets the traveling “Doctor” Dulcamara, who proclaims the virtues of his patent cure-all (“Udite, udite, o rustici”). Nemorino asks Dulcamara if he has the Elixir of Love described in Adina’s book. Dulcamara gives Nemorino a bottle of wine, telling him that it is the magical elixir. Nemorino gulps it down and becomes tipsy. When Adina enters, Nemorino, certain that the potion will work, pretends to ignore her. To punish him, Adina flirts with Belcore, who tells her that he must return to his garrison and so must marry her at once. Nemorino, dismayed by this turn of events, urges Adina to wait just one more day, but she spitefully ignores him and invites the entire village to the wedding.

Act II

Adina’s house. Everyone is celebrating at the pre-wedding feast at Adinas house. Adina secretly wishes Nemorino had come so she could enjoy her revenge. Dulcamara sings a flirtatious duet with Adina (“Io son ricco e tu sei bella”), to great applause. Adina, still miffed at Nemorino’s absence, goes off with Belcore and a notary to sign the marriage contract.

Nemorino arrives, fearing that he is too late to prevent the wedding. Seeing Dulcamara, he begs for another bottle of the magic elixir, but Dulcamara will not give it to him until he can pay for it. Nemorino throws himself on a bench in despair. Belcore now returns, annoyed that Adina has postponed the wedding until that evening. Seeing Nemorino, Belcore asks why he is so sad. Nemorino tells him that he is despondent because he has no money. Belcore advises him to join the army, where he can instantly earn 20 scudi. Nemorino is reluctant, but Belcore persuades him with a vision of the glories (and opportunities for winning the ladies) of being a military man. Nemorino enlists and takes the money, thrilled at the prospect of winning Adina. Belcore secretly plumes himself on having recruited his rival and getting him out of the way.

In the village, Giannetta tells her friends the exciting news that Nemorino’s uncle has died and left him a fortune. Nemorino staggers in, having drunk the second bottle of “elixir.” He suddenly finds himself the centre of female attention, and, not knowing that he has become an eligible bachelor, believes that the elixir is finally working. Adina and Dulcamara arrive and are both astonished to see Nemorino surrounded by the village maidens and fully enjoying his newfound popularity. Adina angrily confronts him about joining the army, but Nemorino, enjoying her jealousy, goes off with a gaggle of girls. Dulcamara tells Adina that the magic elixir has made Nemorino popular, and that he joined the army in order to get the money to pay for it. Adina realizes that Nemorino’s love is true. Dulcamara, seeing an opportunity to sell more elixir, tries to rouse her jealousy, but she vows to win him back her own way.

Alone, Nemorino recalls the tear on Adina’s cheek and is convinced that she loves him (“Una furtiva lagrima”). But when she arrives, he pretends to be uninterested, in order to get her to declare her true feelings. She asks him not to leave and tells him that she has bought back his commission (“Prendi, per me sei libero”). But she still will not confess her love, so Nemorino vows to die a soldier. At last, Adina tells him that she loves him and begs his forgiveness. Belcore arrives to find the lovers embracing. But he is confident that there are plenty of fish in the sea—and that Dulcamara and his love potion can help.

-Linda Cantoni

What style is it in?

L’elisir d’amore is written in the bel canto style, which literally means ‘beautiful song’. Bel canto is all about exhibiting the beauty of the human voice. The orchestra functions to support the singer rather than to compete, and the orchestration is often quite sparse, leaving the voice exposed. This means that the singer’s intonation and vocal technique must be absolutely perfect, making bel canto a challenging style to master.

Donizetti, Bellini, and Rossini were the three leading composers of the bel canto style during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Musical Analyis:

This aria, written in strophic form has a very lovely and moving melody, in bel canto style. Donizetti tried to capture Nemorino’s feelings for Adina through arching melodic lines, opening the aria in an interval of a perfect fifth downward, descending in a minor second, and then going to a minor third upward with a leisurely rhythm.

Sources:

“'Torna a Surriento'.” Classic FM, www.classicfm.com/composers/rossini/.

Green, Aaron. “Translation of ‘Largo Al Factotum’ From ‘The Barber of Seville.’” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/largo-al-factotum-lyrics-and-text-translation-724018.

Schwarm, Betsy, and Linda Cantoni. “L'elisir D'amore.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 4 Apr. 2014, www.britannica.com/topic/Lelisir-damore.

Green, Aaron. “What Does the Famous Aria 'Una Furtiva Lagrima' Mean in English?” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/una-furtiva-lagrima-lyrics-and-translation-724077.

“L'elisir D'amore in a Nutshell.” Opera North, www.operanorth.co.uk/blogs/l-elisir-d-amore-in-a-nutshell.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog No. 8

(1) Chamber or Choral by (1) of the following: Mendelssohn, Schubert, Schumann, or Berlioz.

Mendelssohn Piano Trio No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 66 Description:

This trio was composed during Felix Mendelssohn’s later years, so it is regarded as a late work. Written six years after the first trio in D Minor, this trio was the last chamber work he wrote before his untimely death aged at 38. This work was written for piano, violin and cello.

youtube

Analysis: I. Allegro energico e con fuoco Like the first trio, this was written in sonata form. Two themes occupy this movement with the piano taking a massive portion of the harmonica and rhythmic configurations. This movement is has a stormy character, but it has its lyrical moments. Like the first trio, the piano barely has breathing time in the development sections. This restless movement was written in C Minor II. Andante espressivo This movement resembles the quality of Mendelssohn’s Lied Ohne Worte. It serves as a mere extension of such quality by featuring lyrical lines that are are reminiscent of live singing. III. Scherzo: Molto allegro quasi presto This movement is exhilarating. This is the most technically demanding portion of the trio where the three instruments take equally massive roles in this fairytale movement. Unexpectedly, it rather ends quietly. IV. Finale: Allegro appassionato This movement is rather lyrical than rhythmic as opposed to other third/final movements or Finale movements. Inserted in the movement is Mendelssohn’s quotation of a chorale melody (“Gelobet seist Du, Jesu Christ”, or “Praise to You, Jesus Christ”). Even the development sections are marked by lyrical moments yet very technically demanding. This movement started in C Minor but ended in C Major.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No. 7

(2) German Lieder:

Erlkönig (The Earl King) by Franz Schubert Short Description:

This German Leider is based on the poem that speaks of the journey of a father and child hurrying through the night in a dark, misty forest. Not within the father’s sight was the Earl King wanting to take the child for his own just so that his daughter could have a playmate in his own kingdom. The poem details the struggle of the child and the Earl King until the tragic end comes at the end of the journey. In the father’s arms was his child... Dead!

youtube

Analysis: The song revolves around three themes. It is not necessarily strophic, but these are themes that recur in different modulations in the development before returning to the home key. From G Minor, to C Minor, to B-Flat Major, to C Major, to D Minor and finally back to G Minor.

(2) Widmung (Liebeslied) by Robert Schumann Short Description:

Schumann dedicated his life’s work to his beloved wife, Clara Schumann. This music is a profession of the love from the whole self to his beloved. It is a confession and a celebration of victory in love. The lyrics are aided by one of the most beautiful melodies written for German Lieder.

“Text and Pronounciation Video”

youtube

Performance of Widmung by a German Baritone, Hermann Prey

youtube

Analysis: Explicitly ABA, the song is situated in A-Flat Major whose B section makes a silent and lifted transition to E Major. The B section is characterized by transcendence of love and perfection which lead to a “holy” transition to a series of E Flat seventh chords, the dominant of the home key. The return to A ends with the borrowing of the melody of Ave Maria to signify the bonding of eternal love to one another.

(1) Miniature Piano Piece

Chopin Etude No. 10 in A-Flat Major, Op. 10 Short Description:

Frederic Chopin published his 12 Etudes, Op. 10 when he was just 18 years old. Included in the set is the nicknamed “Revolutionary Etude” (Etude No. 12 in C Minor, Op. 10). This particular etude tackles the double-note piano technique, and in this etude, the double-sixths are the tackled technique.

youtube

Analysis: The same theme is used over two modulations before returning with the same theme in home key. Written in A-Flat Major, to E Major, to A Major to a small development in the dominant (E-Flat Major) and back to A-Flat Major.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog No. 6

Group Performance of the Kings of Classical Music (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven)

Group Mates: Eva Cuenza, Mareal tumanda, joshua Gramaje, Ruzzel Santos, and Trixie Dayrit

Franz Joseph Haydn, (Born March 31, 1732, Rohrau, Austria—died May 31, 1809, Vienna); Austrian Composer

Over the course of his 106 symphonies, Austrian composer Franz Joseph Haydn became the principal architect of the classical style of music.

Synopsis

Franz Joseph Haydn was among the creators of the fundamental genres of classical music, and his influence upon later composers is immense. Haydn’s most celebrated pupil was Ludwig van Beethoven, and his musical form casts a huge shadow over the music of subsequent composers such as Schubert, Mendelssohn and Brahms.

Early Life

Franz Joseph Haydn was recruited at age 8 to the sing in the choir at St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, where he went on to learn to play violin and keyboard. After he left the choir, he supported himself by teaching and playing violin, while studying counterpoint and harmony.

Haydn soon became an assistant to composer Nicola Porpora in exchange for lessons, and in 1761 he was named Kapellmeister, or "court musician," at the palace of the influential Esterházy family, a position that would financially support him for nearly 30 years. Isolated at the palace from other composers and musical trends, he was, as he put it, "forced to become original."

The Mature Artist

While Haydn rose in the Esterházy family's esteem, his popularity outside the palace walls also increased, and he eventually wrote as much music for publication as for the family. Several important works of this period were commissions from abroad, such as the Paris symphonies (1785-1786) and the original orchestral version of "The Seven Last Words of Christ" (1786). Haydn came to feel sequestered and lonely, however, missing friends back in Vienna, such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, so in 1791, when a new Esterházy prince let Haydn go, he quickly accepted an invitation to go to England to conduct new symphonies with German violinist and impresario Johan Peter Salomon. He would return to London again in 1794 for another successful and lucrative season.

Already well known and appreciated in England, Haydn's concerts drew huge crowds, and during his time in England the composer created some of his most popular works, including the "Rider" quartet and the Surprise, Military, Drumroll and London symphonies.

Later Years

Haydn returned to Vienna in 1795 and took up his former position with the Esterházys, although only part-time. At this point, he was a public figure in Vienna, and when he wasn't at home composing, he was making frequent public appearances. With his health failing, his creative spirit outlasted his ability to harness it, and he died at age 77.

Haydn is remembered as the first great symphonist and the composer who essentially invented the string quartet. The principal engineer of the classical style, Haydn exerted influence on the likes of Mozart, his student Ludwig van Beethoven and scores of others.

Works

Haydn is credited as the 'father' of the classical symphony and string quartet, and also wrote many piano sonatas, piano trios, divertmenti and masses, which became the foundation for the Classical style in these compositional types. He also wrote other types of chamber music, as well as operas and concerti, although such compositions are now less known. Although other composers were prominent in the earlier Classical period, notably C.P.E. Bach in the field of the keyboard sonata (the harpsichord and clavichord were equally popular with the piano in this era) and J.C. Bach and Leopold Mozart in the symphony, Haydn was undoubtedly the strongest overall influence on musical style in this era.

The development of sonata form into a subtle and flexible mode of musical expression, which became the dominant force in Classical musical thought, was based foremost on Haydn and those who followed his ideas. His sense of formal inventiveness also lead him to integrate the fugue into the classical style, and to enrich the rondo form with more cohesive tonal logic, (see sonata rondo form). Another example of Haydn's inventiveness was his creation of the double variation form, that is variations on two alternating themes.

Structure and character of the music

A central characteristic of Haydn's music is the development of larger structures out of very short, simple musical motifs, usually devised from standard accompanying figures. The music is often quite formally concentrated, and the important musical events of a movement can unfold rather quickly. Haydn's musical practice formed the basis of much of what was to follow in the development of tonality and musical form. He took genres such as the symphony, which were, at that time, shorter and subsidiary to more important vocal music, and slowly expanded their length, weight and complexity.

Haydn's compositional practice was rooted in a study of the modal counterpoint of Fux, and the tonal homophonic styles which had become more and more popular, particularly the work of Gluck and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, of the later Haydn wrote 'without him, we know nothing'. He believed that the search for an appropriate melody was essential to the creation of good music, and carefully constructed his around countrapunctal devices, so that it could be overlayed with itself in a variety of ways, and the fragments could be worked with individually, and still retain some degree of unique character.

Haydn's work became central to what was later described as the sonata form, and his work was central to taking the binary schematic of what was then called a 'melodie'. It was a form divided into sections, joined by important moments in the harmony which signalled the change. One of Haydn's important innovations, one which was adopted by Mozart and Beethoven, was to make the moment of transition the focus of tremendous creativity, instead of using stock devices to make the transition, Haydn would often find inventive ways to make the move between two expected keys.

Later musical theorists would codify the formal organization in the following way:

Introduction: If present in an extended form, a slower section in the dominant, often with material not directly related to the main themes, which would then rapidly transition to the

Exposition: Presentation of thematic material, including a progression of tonality away from the home key. Unlike Mozart and Beethoven, Haydn often wrote expositions where the music that establishes the new key is similar or identical to the opening theme: this is called monothematic sonata form.

Development: The thematic material is led through a rapidly-shifting sequence of keys, transformed, fragmented, or combined with new material. If not present, the work is termed a 'sonatina'. Haydn's developments tend to be longer and more elaborate than those of Mozart, for example.

Recapitulation: Return to the home key, where the material of the exposition is re-presented. Haydn, unlike Mozart and Beethoven, often rearranges the order of themes compared to the exposition: he also frequently omits passages that appeared in the exposition (particularly in the monothematic case) and adds codas.

Coda: After the close of the recapitulation on the tonic, there may be an additional section which works through more of the possibilities of the thematic material.

During this period the written music was structured by tonality, and the sections of a work of the Classical era were marked by tonal cadences. The most important transitions between sections were from the exposition to the development, and from the development to the recapitulation. Haydn focused on creating witty and often dramatic ways to make these transitions, by delaying them, or by having the occur so subtly that it takes some time before it is established that the transition has, in fact happened. Perhaps paradoxically one of the ways in which Haydn did this was by reducing the number of different devices for harmonic transitions between, so that he could explore and develop the possibilities he found in the ones he regarded as most interesting. This is perhaps why more than any other composer, Haydn is known for the jokes that he put into his music. The most famous example is the sudden loud chord in his 'Surprise symphony|Surprise' symphony, No. 94, but others are perhaps funnier: the fake endings in the quartets Op. 33 No. 2 and Op. 50 No. 3, or the remarkable rhythmic illusion placed in the trio section of Op. 50 No. 1.

Haydn's compositional practice influenced both Mozart and Beethoven. Beethoven began his career writing rather discursive, loosely organized sonata expositions; but with the onset of his 'Middle period', he revived and intensified Haydn's practice, joining the musical structure to tight small motifs, often by gradually reshaping both the work and the motifs so that they fit quite carefully.

The emotional content of Haydn's music cannot accurately be summarized in words, but one may attempt an approximate description. Much of the music was written to please and delight a prince, and its emotional tone is correspondingly upbeat; this tone also reflects, perhaps, Haydn's fundamentally healthy and well-balanced personality. Occasional minor-key works, often deadly serious in character, form striking exceptions to the general rule. Haydn's fast movements tend to be rhythmically propulsive, and often impart a great sense of energy, especially so in the finales. Some characteristic examples of Haydn's 'rollicking' finale type are found in the 'London' symphony No. 104, the string quartet Op. 50 No. 1, and the piano trio Hob XV: 27. Haydn's slow movements, early in his career, are usually not too slow in tempo, relaxed, and reflective. Later on, the emotional range of the slow movements increases, notably in the deeply felt slow movements of the quartets Op. 76 Nos. 3 and 5, the Symphony No. 102, and the piano trio Hob XV: 23. The minuets tend to have a strong downbeat (and upbeat!) and a clearly popular character. Late in his career, perhaps inspired by the young Beethoven (who was briefly his student), Haydn began to write scherzi instead of minuets, with a much faster tempo, felt as one beat to the measure.

Symphony No. 94 in G Major, 2nd Movement (”Surprise”)

youtube

Symphony No. 94

The story of the Surprise Symphony starts with the death of Haydn's great patron, the Austrian prince Nikolaus Esterházy, in 1790. While Haydn's music had been spread across Europe (and even to the Americas in the hands of music aficionado Thomas Jefferson), Haydn himself hadn't left Austria in decades. His music was already popular in England, so a new patron appeared after the death of Esterházy and asked Haydn to come to London for two seasons. An agreement was stuck where Haydn would live in London and compose a total of six symphonies to be performed there.

Symphony No. 94 in G Major was one of these symphonies, which debuted in London on March 23rd of 1791. As the crowd quickly found out, it was full of surprises, showcasing Haydn's wit and ability to play with audiences' expectations.

Haydn knew how to play with audience expectations during a concert

The total work is broken into four movements, a symphonic structure of Haydn's that was still relatively new at the time. The first movement was written in the wrong key, according to the traditions associated with the 4-movement symphony, thus setting up one surprise from the beginning. The first and third movements have a lively feel that was more associated with outdoor concerts than with concert halls. This was especially true of the third movement, a minuet, which was basically the predecessor of the waltz. The second movement contrasts these with a gentler and softer tone, while the fourth escalates it, racing toward its conclusion with a march-like beat.

Overall, Symphony No. 94 in G Major is about 23 minutes of expectation subversion, interplay between tempos and sections of the orchestra, and some very demanding technical sections that reveal Haydn's confidence in the London orchestra. It was one of the works that helped Haydn's 4-movement symphony become the standard that would define orchestral music for generations.

The Surprise

Symphony No. 94 is lively, fun, and full of quirks, but not much more so than any other of Haydn's works. So, why was this one nicknamed the Surprise Symphony? That name actually refers to a single moment in the second movement. In this movement, the pace is gradual, peaceful, and tranquil. The melodies are passive and unencumbered, listing lazily along when out of nowhere BAM! The audience is hit with a jarring and loud chord that crescendos without warning. Surprise!

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756–5 December 1791)

Mozart was one of the most influential, popular and prolific composers of the classical period. He composed over 600 works, including some of the most famous and loved pieces of symphonic, chamber, operatic, and choral music.

“Music is my life and my life is music. Anyone who does not understand this is not worthy of God.”

– Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Short Biography of Mozart

Mozart was born in Salzburg to a musical family. From an early age, the young Mozart showed all the signs of a prodigious musical talent. By the age of five he could read and write music, and he would entertain people with his talents on the keyboard. By the age of six he was writing his first compositions. Mozart was generally considered to be a rare musical genius, although he was also diligent in studying other great composers such as Haydn and Bach.

During his childhood, he would frequently tour various palaces around Europe playing for distinguished guests. Aged 17, he accepted a post as a court musician in Salzburg; although this did not suit him very well, the next few years were a time of prolific composition. In 1781, he moved permanently to Vienna where he stayed for the remainder of his life. In Vienna, he became well known and was often in demand as a composer and performer.

“I pay no attention whatever to anybody’s praise or blame. I simply follow my own feelings.”

– Mozart

However, despite his relative fame he struggled to manage his finances and moved between periods of poverty and prosperity. This difficulty was enhanced when, in 1786, Austria was involved in a war which led to lower demand for musicians. In 1782, he married against the wishes of his family; he had six children but only two survived infancy.

The work of Mozart is epic in scope and proportion. There were few branches of music Mozart did not touch. He composed operas, symphonies, concertos, and solo pieces for the piano. His work spanned from joyful light-hearted pieces to powerful, challenging compositions which touched the emotions. In the beginning of his career, Mozart had a powerful ability to learn and remember from the music he heard from others. He was able to incorporate the style and music of people such as Haydn and J.S. Bach. As he matured he developed his very own style and interpretations. In turn, the music of Mozart very much influenced the early Beethoven.

Mozart was brought up a Roman Catholic and remained a member of the church throughout his life.

“I know myself, and I have such a sense of religion that I shall never do anything which I would not do before the whole world.”

Some of his greatest works are religious in nature such as Ave Verum Corpus and the final Requiem.

Mozart was very productive until his untimely death in 1791, aged 35.

“I never lie down at night without reflecting that young as I am I may not live to see another day.”

In the last year of his life, he composed the opera The Magic Flute, the final piano concerto (K. 595 in B-flat), the Clarinet Concerto K. 622, a string quintet (K. 614 in E-flat), the famous motet Ave verum corpus K. 618, and the unfinished Requiem K. 626.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan. “Biography of Mozart”, Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net, 28th May 2008 Updated 3rd October 2017

Piano Sonata No. 11 in A major ("Alla Turca") K. 331 (K. 300i)

youtube

Musical Analysis

Apart from its foreign influences, the last movement has two other interesting features. The first of these concerns its structure; the movement is a rondo but, unusually, the first theme occurs only twice (traditionally, in rondo form the first theme is presented most frequently in the piece). Therefore, the A major idea from bar 25 becomes the more important as the movement progresses, occurring three times and forming the basis of the coda. Also, Mozart extensively repeats melodic ideas within sections. For example, in bars 8-16 the same melodic idea occurs four times (the second two times transposed down a minor third), and the A major passage at bars 25-32 consists of a repeated motif, with the ending modified on the repeat to allow a perfect cadence to close the phrase. This is a recurrent feature, especially in the coda.

The form of the rondo is A-B-C-D-E-C-A-B-C-coda, with each section (except the coda) being repeated twice.

A: This section, in A minor, consists of a rising sixteenth note melody followed by a falling eighth note melody over a staccato eighth note accompaniment. It is nine measures long.

B: This section introduces new material in a melody in thirds and eighth notes before varying the A section with a cresendo before falling back to piano.

C: A forte march in octaves over an arpeggiated chord accompaniment. The key changes to A major.

D: A piano continuous sixteenth note melody over a broken chord accompaniment.

E: A forte scale-like theme followed by a modification of section D.

Coda: A forte theme consisting mostly of chords (arpeggiated and not) and octaves. There is a brief piano restatement of the theme in the middle of the coda. The movement ends with alternating A and C-sharp octaves followed by two A major chords.

It is worth noting that each movement of the sonata is based around the tonality of A. This is unusual as there is typically a change of key for the second movement to provide a necessary tonal contrast. One can only presume that Mozart considered the huge diversity of material presented in the piece to be sufficient to dispense with this need.

Bar 1-24 The opening theme consists of rising turn-figures which outline an a minor arpeggio. The use of ornamentation continues in bar 5 with grace notes helping to accent the first beat of the bar. A brief diversion to C major in bars 9-12 is short-lived, since it is followed by a return to the tonic. The repeat of the opening idea in bars 17-20 leads to a tonic cadence in a minor, following the reharmonisation of the top C in bar 20 with an Italian 6th chord. This opening section (A) is in itself a miniature ternary form. A surprising number of keys are used at this early stage; a minor, e minor (bar 5) and C major (bar 9) before a return to a minor (bar13). Bars 1-8 have a natural rhythmic accent on the first beat of the bar.

Bar 25-32 A sudden change to the tonic major starts a brash, loud passage which provides an immediate contrast to the preceding passage. The LH uses arpeggiated grace notes for percussive effect. See the background notes for the influence of Turkish music evident here.

Bar 32-56 Once again, a sudden contrast is created through a change of key (f-sharp minor), sudden reduction in dynamics, thinning of texture and bubbling semiquaver passages in the RH. The LH reverts to the texture found at the movement’s opening. In bar 38 the key changes to c-sharp minor to bring the phrase to a close; however, the music then leaps into A major for some scalic RH features that carry on the stream of semiquavers. The f-sharp minor passage returns in bars 48-56, although the second half of this is modified to keep the music in that key and closes with a perfect cadence. This is the ‘C’ section of the structure. The RH melodic cells that open this section contrast well with the a minor theme at the beginning of the movement, since their general shape is an inversion of the turns in the a minor theme. They also start in a descending series, whereas the a minor theme consists of ascending motivic cells.

Bar 56-64 Repeat of bars 24.2-32.1 (the ‘B’ section)

Bar 64-88 Repeat of bars 1-24 (the ‘A’ section)

Bar 88-96 Repeat of the ‘B’ section again, but with the RH octaves broken into pairs of octave-leaping semiquavers. This RH change adds to the percussive, brash nature of the original.

Bar 96.2-127 The coda consists of four presentations of the same A major phrase (bars 96.2-102), with subtle changes, variations in ornamentation and, in bars 109-115, a different texture in the LH accompaniment (an Alberti bass). Other than this , the LH utilises the percussive figure from the previous A major theme. The chord progression in this repeated figure is a very strong I – IV – I – V (resolving onto the tonic to start the next version of the phrase). The last six bars of the piece consist of an affirmation of the tonic A major harmony, bringing the work to a rousing and boisterous close.

"Queen of the Night" aria from "The Magic Flute" by Mozart

The Queen of the Night sings this aria to express her fury and longing for revenge (‘rache’). Mozart chose the key of D minor for this aria. It is a key often associated with tragedy, and prevalent in the Requiem that Mozart was writing, that would dominate his thoughts in the weeks following the premiere of Die Zauberflöte.

youtube

The aria contains marked dynamic contrasts, accents land on and off the beat and the vocal line is often highly chromatic. Rather unexpectedly, after the opening bars the music suddenly moves to F major, the relative key of D minor. Gaining in confidence, the Queen scales the vocal heights. The Queen tells Pamina that if she does not kill Sarastro as the mother has asked then she will no longer be her daughter, and sings a series of repeated notes on a high C before climbing even further to several dizzying top Fs. Nothing, it seems, can stop her.

After Sarastro’s thoughtful hymnic aria ‘O Isis und Osiris’, the Queen’s virtuosity is all the more staggering. And however hollow her threats will prove – she clearly does not know her daughter’s moral strength – the aria could not make its point any clearer. The recurrent gestures, manic twists and turns and final ferocious D minor cadence place a thrillingly thunderous cloud of wrath over the proceedings.

Sources:

“Franz Joseph Haydn.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 5 Jan. 2017, www.biography.com/people/franz-joseph-haydn-9332156.

“Franz Josef Haydn.” Prince Biography, www.8notes.com/biographies/haydn.asp.

Study.com, Study.com, study.com/academy/lesson/haydns-surprise-symphony-analysis.html.

https://www.biographyonline.net/music/mozart.html

https://sensq.com/blog/story-of-rondo-alla-turca-turkish-march

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog No. 5 (Ch. 22 Assignments)

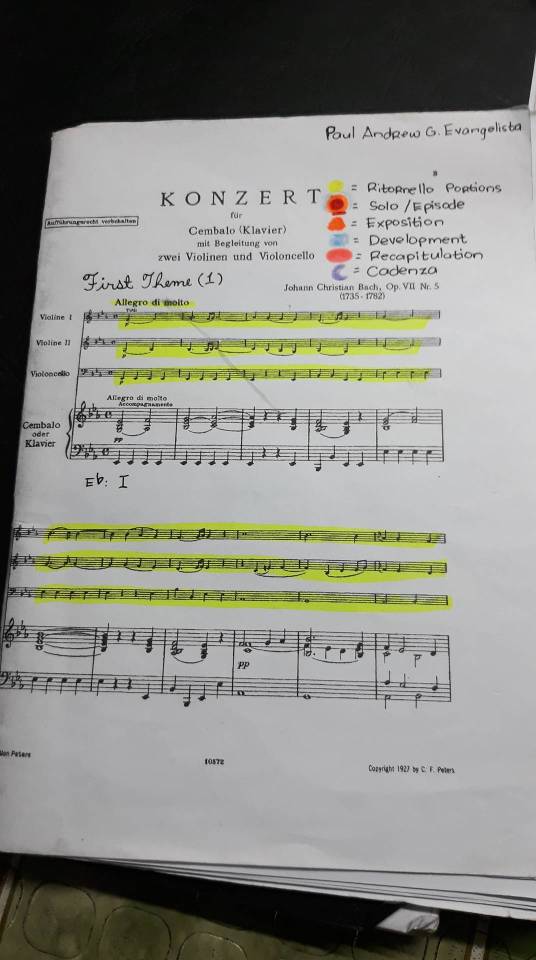

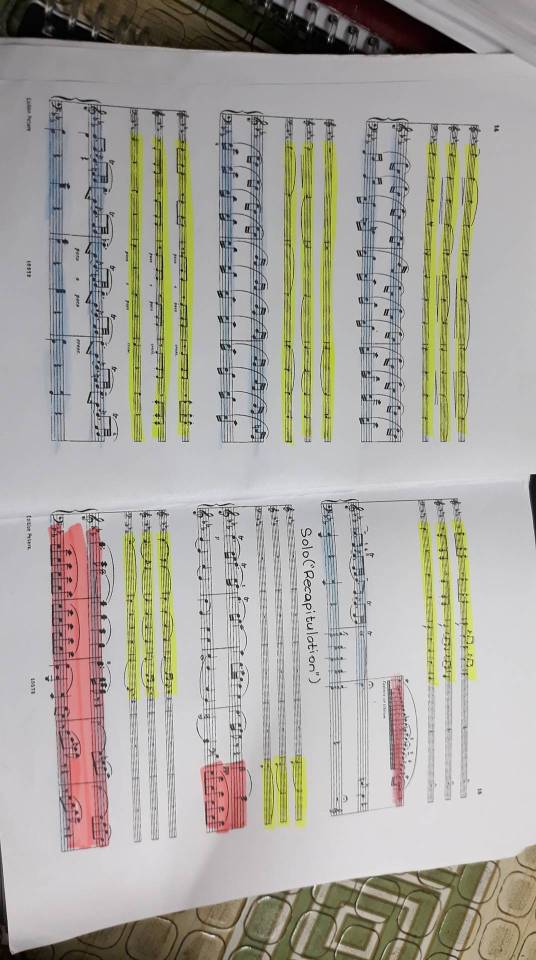

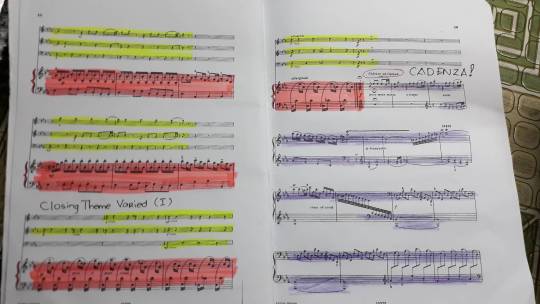

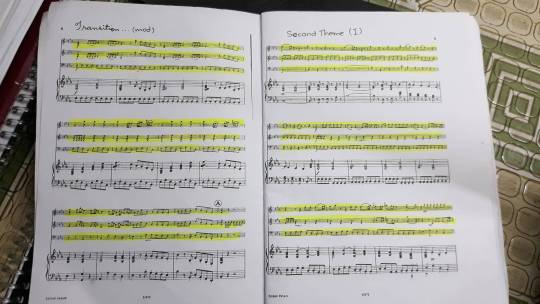

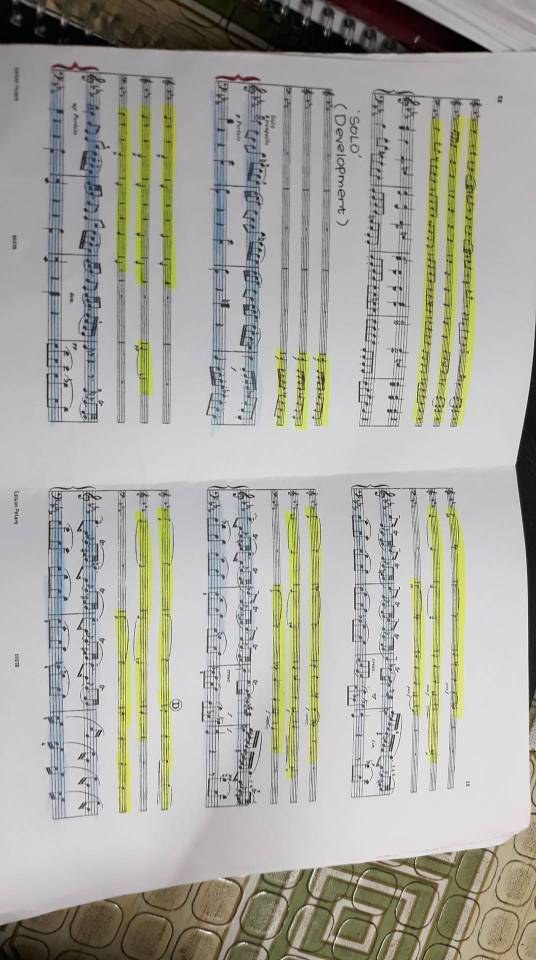

Musical Analysis of J.C. Bach’s Concerto for Keyboard and Strings in Eb Major:

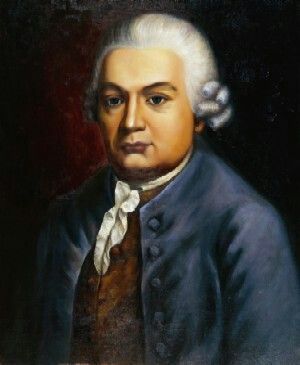

J. C. Bach's keyboard works include several sets of accompanied sonatas, a genre that enjoyed a wide popularity during the Classical era, but never found its way into the concert repertoire. The accompanied sonata was a genre meant for domestic performance; the solo keyboard sonata, on the other hand, was adopted in due course by concert audiences. J. C. Bach composed works within both genres during most of his productive years, and his output constitutes a corpus of remarkable consistency. J. C. Bach's removal to London in 1762 coincided with his clear adoption of a galant style, marked by the Italianate influence, and the abandonment of most Baroque traits. The British milieu provided additional factors: the rise of the pianoforte, a thriving music-publishing market, and a great interest in domestic music making among the affluent classes. These factors marked J. C. Bach's output at various levels. Keyboard works had to conform to the proficiency of the amateur performer, a fact reflected in the accompanied output mostly. The number of movements, their length, and the inclusion of particular technical devices are readily observable differences between the two genres. The most remarkable distinction lies perhaps in the preference for binary sonata format in the accompanied. sonatas from the mid 1760s to the 1770s, in spite of a later tendency for tripartite designs in both genres. J. C. Bach's lifelong preference for motivic phrase structure conditioned his keyboard production and partly explains the gap in quality between some of his works and sonatas composed around the same time by Haydn and Mozart, who developed more effective means to connect the melodic material to higher structural units. J. C. Bach's influence, however, endured in Mozart's handling of melody, and his keyboard production constitutes, in spite of some flaws, a noteworthy example of elegance and craftsmanship.

Source: Carvalho, Marinho Silva, and Helen Paula. “J.C. Bach's London Keyboard Sonatas : Style and Context.” White Rose ETheses Online, University of Sheffield, 1 Jan. 1970, etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/3070/.

A. Carl ‘Karl’ Philipp Emanuel Bach: (Born March 8, 1714, Weimar, Saxe-Weimar [Germany]—died Dec. 14, 1788, Hamburg); German Composer

A precocious musician who remained successful, C.P.E. Bach was his father’s true successor and an important figure in his own right.

Successful in assimilating the powerful influence of their father and in making the transition into the new style then evolving.

Became a leader of that movement but retained the advantage of a solid craftsmanship and assurance for which he always gave full credit to his father’s teaching and example.

His symphonies, concerti, and keyboard sonatas were influential in the evolution of classical sonata-allegro form.

His influence on Joseph Haydn, W.A. Mozart, and even Ludwig van Beethoven was freely acknowledged.

As a performer, Bach was famous for the precision of his playing, for the beauty of his touch, and for the intensity of his emotion.

The influence of C.P.E. Bach’s Essay on Keyboard Instruments was unsurpassed for two generations. Haydn called it “the school of schools.” Mozart said, “He is the father, we are the children.” Beethoven, when teaching the young Karl Czerny, wrote, “be sure of procuring Emanuel Bach’s treatise.” It is, indeed, one of the essential source books for understanding the style and interpretation of 18th-century music. It is comprehensive on thorough bass, on ornaments and fingering, and is an authentic guide to many other refinements of 18th-century performance.

B. Giovanni Battista Sammartini: (Born 1700/01, Milan [Italy]—died Jan. 15, 1775, Milan); Italian Composer

An important formative influence on the pre-Classical symphony and thus on the Classical style later developed by Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

He was one of the first to compose symphonies for concert performance; their ancestry was in the Italian opera overtures. As his orchestral and chamber music became known outside Italy, it attracted pupils to Milan, among them Christoph Gluck, who probably studied with him in 1737–41.

Widely regarded as "the father of the symphony." While he may not have invented the form, he was the first composer to master it and helped establish it as a separate entity from its direct ancestor, the opera overture.

Sammartini was a prolific composer; by some estimates, he produced 2,000 works.

C. Johann Christian Bach: (Born Sept. 5, 1735, Leipzig [Germany]—died Jan. 1, 1782, London, Eng.); German Composer

J.C. Bach’s music reflects the pleasant melodiousness of the galant, or Rococo, style. Its Italianate grace influenced composers of the Classical period, particularly Mozart, who learned from and greatly respected Bach.

His symphonies, contemporary with those of Haydn, were among the formative influences on the early Classical symphony; his sonatas and keyboard concerti performed a similar role.

Although he never grew to be a profound composer, his music was always sensitive and imaginative.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog No.4

Opera Reform: Dissatisfaction arose in some quarters with the excesses of Italian opera seria—especially its predictable use of recitative and aria and its catering to solo coloratura (an elaborately embellished vocal melody) and other ornamental features that impeded the action. Consequently, some Italian composers began to move the genre in the direction of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s powerful and more integrated tragédies lyriques. Tommaso Traetta and Niccolò Jommelli, who worked at courts where French taste prevailed, often used orchestrally accompanied recitative (a technique known as recitativo accompagnato) to smooth the transitions between secco (“dry”) recitative and da capo aria. They also gave greater importance to ensembles and choruses, which had long been absent in opera seria.

That dedication—a manifesto, really—is the central document of “operatic reform.” It stated that the “true office” of music is “serving poetry,” a goal hindered by the “useless and superfluous ornaments” with which the florid da capo arias were encumbered. Rather, a “beautiful simplicity” and naturalness of expression combined with emotional truth were to hold sway. In short, Gluck and his collaborators were responding to Enlightenment ideals and restoring opera, albeittemporarily, to its function as drama set to music. The most significant manifestations of these principles were the Calzabigi-Gluck Italian operas first staged in Vienna: Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), Alceste (1767), and Paride ed Elena (1770; “Paris and Helen”). The two earliest of these became even more stately and Rameau-like when Gluck reconstituted them to French librettos for Parisian audiences.

Source: Weinstock, Herbert, and Barbara Russano Hanning. “Opera.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 3 May 2018, www.britannica.com/art/opera-music/From-the-reform-to-grand-opera.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No. 3

La Serva Padrona: One of the most successful comic stage works of the entire eighteenth century, Pergolesi's intermezzo La serva padrona was first produced in Naples at the San Bartolomeo theater on September 5, 1733. The function of such works was to serve as an entr'acte piece between the acts of a substantial opera seria -- in this instance Pergolesi's own Il prigioniero superbo, a work subsequently eclipsed by the fame of the intermezzo.In keeping with the characteristics of the genre, the plot and design of La serva padrona are extremely straightforward; there are only two short acts, and only three characters, one of whom is a mute male servant. The two singing parts are for a middle-aged man, Umberto, and his pert servant Serpina, both drawn from the traditions of commedia dell'arte. The plot concerns Serpina's tricking Umberto into marriage. Pergolesi's music clothes this inconsequential but naturalistic domestic drama in a rich vein of characterization and vitality; the simplicity of means employed would prove enormously influential in the development of comic opera. It is this feature that has led to the mistaken idea that Pergolesi was the founder of opera buffa -- a distinction that more properly belongs to one of his teachers, Leonardo Vinci. This opera is a full-length work with six (6) or more singing characters and was sung throughout. The plot is centered on ordinary people in the present day in contrast to the stories of myth or history in serious opera. The themes of Opera Buffa were mostly foibles of aristocrats and commoners, vain ladies, misery of old men, deceitful husbands/wives, and prostitutes. The plots of Opera Seria were somehow intense,serious, and grave but on the other hand, Opera Buffa plots were light.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Link

Blog No. 2: Bach’s life and Cantata Cycles

Group mates: Michelle Mariposa and Paul Anthony G. Evangelista

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog No.1

Summary of Vivaldi’s Ritornello Style as applied in his Concerti: Vivaldi’s concertos have a freshness of melody, rhythmic verve, skillful treatment of solo and orchestral color, and clarity of form that have made them perennial favorites. Ritornellos for the full orchestra alternate with episodes for the soloist or soloists. The opening ritornello is composed of several small units, typically 2-4 measures in length, some of which may be repeated or varied. These segments can be separated from each other or combined in new ways without losing their identity as the ritornello. Later statements of the ritornello are usually partial, comprising only one or some of the units, sometimes varied. The ritornellos are guideposts to the tonal structure of the music, confirming the keys to which the music modulates. The first and last statements are in the tonic; at least one (usually the first to be in a new key) is in the dominant; and others may be in closely related keys. The solo episodes are characterized by virtuosic, idiomatic playing, sometimes repeating or varying elements from the ritornello, but often presenting scales, arpeggiations, or other figuration. Many episodes modulate to a new key, which is then confirmed by the following ritornello. Sometimes the soloist interrupts or plays some part of the closing ritornello.

Vivaldi Concerto in A Minor: Form and Structure

Ritornello: (ascending and descending passages) --> Episode: 8 measures (Arpeggiated) ---> Ritornello --> Episode (Scales and Arpeggios) --> Ritornello (Change of Tonal Center) --> Episode (Back to A Minor) --> Ritornello

youtube

Summary of Rameau’s major points in Traite del Harmonie: Each chord has a fundamental tone, equivalent in most cases to what is today is called its root (the lowest note when the chord is arranged as a series of thirds). In a series of chords, the succession of these fundamental tones is the fundamental bass. He considered the triad and seventh chord the primal elements of music, and derived both from the natural consonances of the perfect fifth, major third, and minor third. Seventh chords provided dissonance, triads of consonance. He coined the terms tonic (the main note and chord in a key), dominant (the note and chord a perfect fifth above the tonic), and subdominant (the note and chord a fifth below the tonic); established those three chords as the pillars of tonality; and related other chords to them, formulating the hierarchies of functional tonality. He recognized that a piece could change key, a process called modulation, but considered that each piece had one principal tonic to which the other keys were secondary.

1 note

·

View note