Text

Adalwolf is staring into an empty, gray sky. He hears no sound but the call of the marsh hawk in the distance. His lungs burn on the smell of blood, but nothing else hurts anymore except the cold stabbing his bare knuckles through the bailey’s cobble. He tries to sit up but can’t. He tries to turn his head but can’t. Everything feels like lead. He tries not to sink into the ground which seems more like the River Cairns now. He does anyway, and blackness takes him.

*

You never forget your first brush with death because it becomes the index by which you measure all other experiences of its class and magnitude. Adalwolf remembers that when he was seven, maybe eight, his father had taken him hunting along the banks of the River Cairns. Its dark, deceptive waters looked placid then as they do now and always, but any man over the age of fourteen will tell you that a calm river is like an honest Vygantine; they do not exist. At the time, though, Adalwolf was unbearded and unblooded and had yet to make bed with the violence of the natural world, his father having done the disservice of sheltering him from its bite.

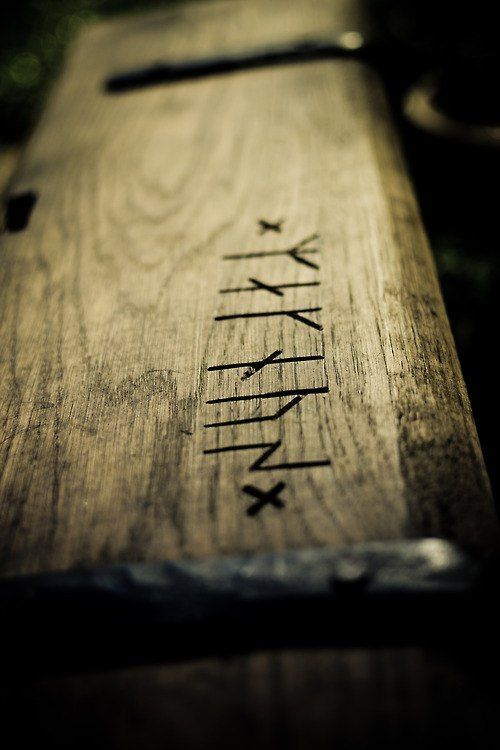

The Bärvolk hunt on horseback as much as any southerner, but their forefathers were river people and today they hound their game by way of a skiff that he and his father had crafted of their own two hands the previous summer. It slices through the water with ease, very little need to tend her except to keep her nose forward. The morning is just at the crest of noon and there is a cool breeze drawing through the warm swale. His father watches the walls of switchgrass encircling them. Adalwolf inspects his bow. The craftsmanship is fine, its surface engraved with wolves, babes, babes carried off by wolves, the great bear at its center, and strange geometric figures he has not yet learned. Ada had whittled and strung the bow before gifting it to him, but he knew by Yana’s knowing smile that it had been she who etched it. He finds it hard to look away from the icons, his eyes wide with wonder.

As Björnard maneuvers the skiff through a riverbend, the nearby switchgrass twitches. A hare, previously supping water, now stands still on the shore. Adalwolf thinks it's strange how one creature can recognize the fear in another creature’s eyes. The switchgrass erupts and issues forth a lank flash of red from its great green curtain to maul the hare where it stands. The fox is the victor. Björnard gestures to Adalwolf, low and wild. Adalwolf stares.

The bow, you daft boy, bring the bow, he says. Adalwolf brings the bow, the bow and arrow, the flensing knife, the oar, the father trades him the bow for the oar and stands by. This is your kill, he says. It don’t need to suffer, boy, aim for the heart.

Adalwolf, even at his age, is no stranger to a bow. He has done this a few times before and knows the proper posture. He kneels near the skiff’s edge and takes aim. He stares grimly against the whipping wind, the way he imagines his father would look. He hopes his father is proud. His heart thrums like the wild hare and the tension in the bowstring is good: made for the young, but no less deadly. He is a pose of severity, but just a pose. He is not severe – not enough, not at heart – or he would have minded his shifting weight and the skiff’s cocking. He would have respected the deep and endless dark below, but he hadn’t, and now, with the boat beginning to tip, the water lurches up towards him.

The cold, thousand-strong arms of the Cairns, as jealous as fae, seize the boy and drag him down into their deepest shames. The river is cold year-round, and it cuts immediately to the bones; it strangles him. If there is a bottom to this beast, he never touches it as she sucks him through her hungering gullet. He holds his breath even as the chill makes him want to scream, makes his eyes burn and his skin feel like they’ve been set on fire. Light explodes around him through a watery film, just for a moment. He desperately draws breath. The Cairns drags him under again and he is tumbling through her void. And then, somewhere in that great, dark womb, he slips into something darker yet, and he is no longer afraid.

We are the sons of no country, his father says, somber, as he holds him by the fire, in a place out of time. He runs his fingers through his son’s hair and hums a low and resonant gwerz. A deluge of water pours from the hearth and drowns them.

*

Eyes open. A silhouette rises grim against a gray backdrop. Although he cannot hear him, he knows the silhouette is his uncle by the vibrations of his powerful voice. Don’t move, maybe if you don’t move, he’ll leave. Stare. Just keep staring. Don’t blink. Adalwolf blinks. Sound sucks back into the world as if through a funnel. An incoherent whistle at first. The marsh hawk calls again, accompanied by the noise of small things ferreting through the grass. The hollow, staccato of splitting wood echoes through the vacant air.

“How poor, we, to be cast with such a noose. Get on up, you boy,” his uncle says. Adalwolf opens his mouth but there’s only a wheeze. “You make truck with the devil? Then let us temper him with iron. Get on up, I said. Take the iron: show me what form of man you are.”

Adalwolf thinks he’s in the bailey, still, but Cyneard might have kicked him out of the gate by now. He feels embarrassed. He must look incompetent to the villagers or his family or to god. He wonders if his Völva is watching as he rolls over and coughs. There is an awful pain in his shoulder, and he thinks it might be broken. Adalwolf knows his uncle loves him, but something changed in him when Björnard died. He is thinking about his father and the pain in his shoulder when he begins to wail. The waters of the Cairns rise up around him again.

*

He doesn’t know when he got back to his feet, but Adalwolf is looking into deep, dark eyes. A formless phrase floats around inside his head, but he doesn’t know what it means, and Cyneard’s hand is covering his mouth, so it doesn’t matter. He is trying to quiet the boy’s wailing while hazarding looks over his shoulder. Do you want your mother to hear, hush now boy, hush. He tries to stop but doesn’t know where his mouth is – or his hands or head, even. He’s crawling up from somewhere far at the back of the deep tunnel that must be his eyes when sensation hurtles back into being. It takes every ounce of willpower in him to not only stop wailing, but also to manage a suppressed shriek. Too late, though: Kriemhild’s great voice vaults across the bailey:

“Unhand him, you miserable cur, or I will break your legs and send you crawling through the muskeg naked. Do you hear me? I said: unhand him, or gods help me, I will end you, brother.”

Adalwolf sees now that he had never been standing. He’s on his back while Cyneard is straddling his hips and looking at Kriemhild across the cobble. His hand leaves Adalwolf’s mouth and in that moment, thoughtless, Adalwolf sounds out that phrase in his head he’s heard only once before. It feels thick and clumsy and wrong on his tongue, but everything beneath his skin feels alive when it leaves him. Cyneard’s head snaps back to look down at him as if struck, his face a mask of bloodless horror as the boy grabs his uncle’s arm and carves coarse, uneven fingernails into the skin. Blood wells to the surface just as he strikes Adalwolf’s face. The young boy, weak with fatigue, succumbs to the darkness.

*

That evening, someone from the village with a steady eye and a small voice visits the family and tells them that there are wolves out in the marsh and to stay inside. As the evening gray sinks into night, Adalwolf is at the fire, nursing his shoulder-sling. The soreness is beginning to set in, but he knows the worst is yet to come. By way of horse or carrier pigeon, there is somewhere a courier carrying dark parcels. The morning sun will shine a new kind of pain across his body and he will be immobile for two, maybe three days. But this is only an afterthought. A fever dream has taken his uncle by the hand and now leads him down into a delirium that fills their great hall with yammering and cries. He has seen him in the back room, drenched in sweat, the bedding one acid-yellow wash of colour. There is an awful droning of flies. He hears the baying of the wolves, their blackened figures lit by starlight on distant hills. To keep him from hurting himself, Kriemhild eventually restrains Cyneard’s wrists and ankles by winding up old cloths and sheets into cords and tying them off to the bedposts. He says he sees eyes in the windows, in the dark corners of the room. He says a man is sitting at the foot of his bed and that his stare hurts. There is something wrong in the air. Adalwolf bundles up in furs to shut out the noise. Kriemhild is sobbing, holding her brother close as the nightmares deepen. The flies are screaming. Sometime, just beyond midnight, he falls still at last and all is quiet save him, and he is murmuring. He says: “The Shoemaker King comes with many crowns to this, His house.”

And then he sleeps – a deep, black, dreamless sleep that endures for three days. And when he wakes, he will never look at Adalwolf again.

0 notes

Text

i had slept

I was asleep. I had slept. I am kneeling before a small bowl filled with viscera. My hands are bloody and I can see their prints along the inside of the bowl. I have lost time. Seven deep breaths to settle the nerves and two wobbling knee-knobs later I am back on my feet. My body feels alien after a blackout: unfamiliar, incongruent. The strangeness will pass eventually.

I am in a hide-strung yurt, hung with charms made of coloured glass and mirrors. There is a dead fire here. Outside is a pale forest, the snow-covered ground and the trees a subtle glow stretching out beyond knowing. A trail of blood leads away into the woods. I want to run, to be safe. I want to find mother or father. I know I should, they would know what to do, but mother is very busy this time of year and my father lays with his father. I should be cold, naked in the snow, but I’m not. I should be running: a thousand eyes watching me, ringing the black. Seven deep breaths to settle the nerves. I’m walking now. Yana is there and she’s not there. I can see her walking next to me out of the corner of my eyes sometimes, but she doesn’t talk, and I don’t want to look at her. I know she is smiling. She wants to show me something. Something that I don’t want to see. My jaw hurts, or it hurts more than everything else. There is an ache in my stomach or in my loins, I can’t tell where. My feet are moving faster, now.

There is a voice and it’s not Yana’s, but it is familiar. He or she says: “you don’t have to hold on so hard, you know,” and then I am running, and then I remember: this is a dream. A dream where you are in a great, white wood and you are always running, and you never run fast enough because it catches you in the end, every time. A dream with a wolf, but not any kind you’ve ever seen, antlered like elk or caribou. Too many eyes and too many tongues. Bipedal or six-legged, it decides. A dream where you know it is a dream, but you run anyways, because if you don’t you somehow know it gets worse. Somehow the wolf takes more. A dream where, maybe you wake up, and if you do, you tell yourself every time:

The wolf is not me.

0 notes