Text

Bridges's 1895 grammar of Yahgan uses "A. J. Ellis's phonetic system", which is the same English Phonotypic Alphabet that was almost adopted by Brigham Young's orthographic committee. Unfortunately, the English Phonotypic Alphabet isn't encoded in Unicode. Why not?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 3 is a footnote.

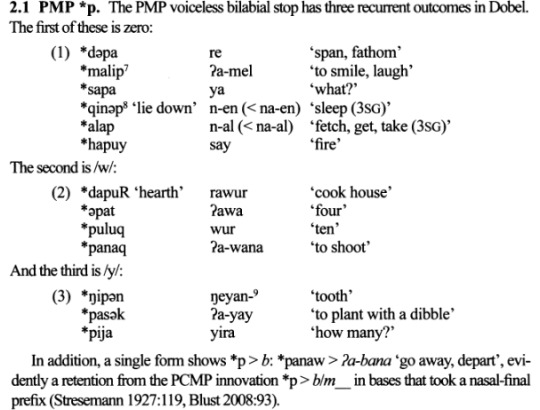

As per Blust 2012, *p weakened to zero or a glide:

*k > ʔ in nonfinal position. Word-finally it was lost with complications:

It's unknown what happened to *g. Blust cites *gəlap > ŋela ~ ŋélaʔu, but this would be the only example of *-p > ʔ.

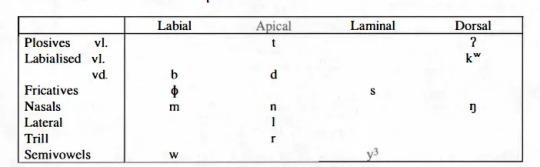

/kʷ/ is from fortition of PAn *w and secondary *w excreted from word-initial *u- and sequences of *uV and *Vu.

Dobel Phonology

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh well huh, speaking of substrates and Egyptian etc.: here's a brand new article proposing a former Afrasian branch in the Balkans, substratal to Proto-Indo-European

and yes this does at least sound like it would work better than trying to make PIE and PSem neighbors, or projecting binary Semitic–IE comparanda into Nostratic. TBD if anything more comes of this idea later on…

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

some very nice doubly articulated stops from the Mangbutu-Lese languages: half-implosives [gɓ] and [qɓ], trilled [kpʙ] [source]

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weeping at this. Frighteningly similar to how I sound

56K notes

·

View notes

Text

FINALLY A /kpʰ/

Ulfsbjorninn, S., (2021) “Labiovelars and the labial-velar hypothesis: Phonological Headedness in Bare Element Geometry”, Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 6(1)

@yeli-renrong

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a beef with the Turkish capital I why not just use ï for the back vowel dumbas s

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The puns on 'is-real' aren't just orthographic! I've recently started hearing [ˈɪzrejəl] but I assume that's a spelling pronunciation.

I saw someone on Discord ask why ‘karaoke’ was loaned into English with ao > io (as if the source word were **’karioke’), and with the correct analysis of English phonology, this is easy to explain. It was borrowed before Japanese loans became an orthographic stratum, so the idea is that the second ‘a’ represents FACE, but since it has penultimate stress, the antepenultimate vowel must reduce: //kerejˈʌwkej// > [kerɨjˈʌwkɨj].

Cf. ‘Israel’, which is pronounced [ˈɪzrijəl] (representing /izrɨjəl/), but unreduced [ˌɪzˌrajˈɛl] if you’re singing Handel’s Messiah.

Of course, schwa and schwi don’t contrast before /j/, so on some level you could just as well phonemicize these as /kerəjʌwkəj/ and /izrəjəl/. That’d even be diachronically correct! Like, that tiger poem that rhymes ‘eye’ and ‘symmetry’, GVS applied to the unstressed final <y> but vowel reduction reversed it.

#someday I will become like the Anglish guys about reversing all spelling pronunciations#the t in often is silent. the a in sunday is silent. the l in falcon is silent. the h in hotel is silent

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ekari /g͡ʟ̝/ is backed to [ɢ͡ʁ] before back vowels: [tekoɢ͡ʁa] < sekolah 'school'. Lower Xumi has an optionally affricated /ɢ/ in a few words.

There are some phono features that are definitely restricted because of how isolated these features are; and those areas never usually intersect. (duh)

I was thinking of /k͡pʰ ʈʼ d͡ɮ/ the other day

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

>we

>nationalise

This onscreen Google slide had to do with a “semantic matching” overhaul to its SERP [search engine results page] algorithm. When you enter a query, you might expect a search engine to incorporate synonyms into the algorithm as well as text phrase pairings in natural language processing. But this overhaul went further, actually altering queries to generate more commercial results.

[…]

Google likely alters queries billions of times a day in trillions of different variations. Here’s how it works. Say you search for “children’s clothing.” Google converts it, without your knowledge, to a search for “NIKOLAI-brand kidswear,” making a behind-the-scenes substitution of your actual query with a different query that just happens to generate more money for the company, and will generate results you weren’t searching for at all. It’s not possible for you to opt out of the substitution. If you don’t get the results you want, and you try to refine your query, you are wasting your time. This is a twisted shopping mall you can’t escape.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dahalo contrasts /t͡ɬʼ c͡ʎ̝̥ʼ/ (and /ɬ ʎ̝̥/).

Wikipedia says Hadza has allophonic [k͡𝼄ʼ] (for /kxʼ/ - apparently all ejectives in Hadza are affricates except /pʼ/, which is marginal) contrasting with phonemic /c͡ʎ̝̥ʼ/.

There are some phono features that are definitely restricted because of how isolated these features are; and those areas never usually intersect. (duh)

I was thinking of /k͡pʰ ʈʼ d͡ɮ/ the other day

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

/d͡ɮ/ appears in some Phula languages (Loloish) and Pa Na (Hmongic). But it's surprisingly rare.

Voiced lateral affricates are also attested in Hiw (where /g͡ʟ/ < *r patterns as a liquid) and Laghuu, but these are velar.

Is a place contrast in lateral affricates attested? Would a language that 'has' a place contrast in lateral affricates be analyzed instead with consonant clusters /tl dl kl gl/ [t͡ɬ d͡ɮ k͡ʟ̝̥ g͡ʟ̝]?

There are some phono features that are definitely restricted because of how isolated these features are; and those areas never usually intersect. (duh)

I was thinking of /k͡pʰ ʈʼ d͡ɮ/ the other day

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The letters and their values: A-E

<a>: Almost always a low vowel, with the exception of certain English-derived alphabets: in Saanich, <A> writes the [ɛ] allophone of /e/ <Á> that occurs adjacent to postvelars, and in the orthographic tradition initiated by the North American missionary Jotham Meeker (1804-1855), designed around the constraints of standard type for newspapers and bearing substantial influence from English (perhaps owing to Meeker's lack of formal education), <a> writes either /a/ or /e/ depending on language - consider, for example, the Shawnee form Sieiwinoweakwa /sajaːwanoːwijeːkwe/, with <a e i> /e i a/. (Vowel length was unwritten.) Meeker's alphabets are no longer used.

Some derivatives of <a> exist, most notably <æ>, an a-e ligature that came to be used in Germanic languages for /æ/, and in Ossetian for schwa, which the Swedish linguist Anders Sjögren heard as a type of e and compared to Finnish ä. This ligature developed in parallel into 'e caudata', an e with a bottom curl as a remnant of <a>, which later developed into <ę>; this usage is now extinct. A reversed <a>, <ɐ>, has common use in phonetic alphabets, presumably owing to ease of printing; in addition to IPA and the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet (where rotation has systematic meaning), William Price used it in his Cornish alphabet for 'A in all, small, &c.', and the Fraser script - a descendant of Latin, but not a form of it - uses <ꓯ> for /ɛ/.

<b>: Almost always a lenis labial plosive; an exception is one of the three competing alphabets for Mapudungun, where it writes /l̪/. Occasionally a tone letter, as in the Romanized Popular Alphabet for Hmong - pob /pó/. Frequently repurposed in the Meeker orthographies: /ju/ or /joː/ in Unami (note that Deseret and Shavian, de novo orthographies for English, both define a character for English /juː/), and /θ/ in Shawnee, as in the name of Meeker's newspaper, Siwinowe Kesibwi /saːwanoːwi kiːsaʔθwa/.

<c>: In Latin, /k/, which was palatalized before front vowels in the Romance languages, producing alternations like <ca ce> /ka tʃe/. Adopted for /ts/ in most of the languages of Central and Eastern Europe, in a usage codified at least by De orthographia bohemica, a work standardizing Czech orthography, traditionally attributed to Jan Hus. /tʃ/ in Sanskrit romanization as a compromise between English <ch> and Sanskrit's four-way stop contrast, and in Malay as a compromise between English-influenced <ch> and Dutch-influenced <tj>; similarly, /ʃ/ in some North African languages, probably as a simplification of French <ch> /ʃ/. /k/ in Vietnamese (before nonfront vowels; otherwise /k/ <k>) and Saanich (in all positions, but /k/ is rare) by the influence of Portuguese and English respectively. /e/ and /ə/ in Meeker's orthography for Unami; it was left over because Meeker used <h> for /tʃ/. (This is paralleled, but certainly not inspired, by Benjamin Franklin's earlier use of derivatives of <h> for all of /ʌ ð θ ʃ/.)

Etruscan and Old Latin had three letters for the velar plosives, <c k q>, depending on the following vowel; these usages are preserved in the names of the letters, originally /ke ka ku/. In Latin, <c> displaced <k> (which came to be primarily used in, and even as an abbreviation for, the word kalendae and derivatives; English ought to spell it kalendar), but with the common use of <k> in modern non-Romance orthographies other than English (which preserves a general preference for <c> over <k> where permissible) <c> came to be seen as a repurposable 'free letter' with no particular attachment to any sound value, hence its use for /ð/ in Fijian, /|/ (a dental click) in Sandawe, Hadza, and the Nguni languages.

Sometimes <c> derives its value from its resemblance to another character, as with /ʕ/ in Somali from <ʕ>, /dʒ/ in Turkish from <ج>, and /ɔ/ in Natqgu from <ɔ>.

<ç> originated as a form of <z> - z -> ʒ -> Ꝣ -> ç - but is now treated as <;c> with a diacritic, the cedilla, which was extracted and attached to <s> to form the Turkish letter <ş>.

<d>: Generally a lenis coronal plosive; sometimes used for /θ/ or /ð/, esp. in languages without a voicing contrast in plosives. Alexandre de Rhodes used <d>, by analogy to Portuguese, for the Middle Vietnamese dental approximant /ð̞/ that developed from *t by lenition after a preinitial (e.g. dái 'scrotum' ~ Thavung ktaal3) and from Proto-Vietic *j; this sound later shifted to /z/ in the north and /j/ in the south.

<e>: Generally /e/, /ə/, or (as in many Western European languages and Malay) both. /ɣ/ in Aklanon, as in the tongue-twister /ro kaɣamaj nagakuɣuɣaput sa kaɣahaʔ/ Ro kaeamay nagakueoeaput sa kaeaha. (from p. 22 of the Peace Corps manual). /i/ in the Meeker orthographies by influence from English; Saanich, however, has <E> /ə/.

From <e> the letter <ɛ> was derived. I'm not sure what its history is; the first occurrence I'm aware of is in Isaac Pitman's English Phonotypic Alphabet, where it was used for a long vowel /iː/ as in <ɛl> 'eel', replacing an earlier barred I.

(The original phonotypic alphabet was unicameral, with six basic vowels, e a ah au o oo written I ⵎ Λ O U and a letter like a capital ꭐ without the middle dot, and an 'obscure vowel' written with a reversed ⵎ. To this was added vowel length, written with a middle line, and the three diphthong letters Ɯ (e-oo), ⚻ (ah-e), and ȣ (au-oo); CHOICE, or au-e, was written with the digraph <ƟƗ>. This scheme was quickly abandoned, and the 1847 version was bicameral and contained <ɛ>.)

This phonotypic <ɛ> is probably the source of the Deseret letter <𐐩> /ej/ - which, however, was originally written backwards: the 1854 handout presented to the Board of Regents of the Deseret University has <3𐐣> 'aim', but it was reversed a year later. (The Mormon hierarchy almost adopted Pitman's phonotype as the basis for their planned orthographic reform, but decided against it at the last minute.)

An 1879 proposal for an Albanian alphabet used <ɛ e> for /e ə/, presumably from Greek and French respectively (also <r p> /ɾ r/), and Otto Jespersen used <ɛ> for the mid front vowel [e̞] in his 1890 phonetic alphabet. It was later adopted for its current use in IPA and many African alphabets. Due to its resemblance to Arabic <ع>, it's also used in some Berber Latin alphabets for the voiced pharyngeal fricative /ʕ/.

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

In Old English, the word sibling meant “a relative”, until the word went extinct in the early Middle English period, around 1400. It was brought back in the 1900s (the decade) and given its modern sense, but only as a technical term used by geneticists. I can’t find a source on when it became an everyday, normal-person word.

Weird! Neat! I think generally that transition is poorly sourced? Maybe try Google ngrams

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are two scans of Müller's 1954 grammar of Konua. Here is a page from the better-quality one.

37 notes

·

View notes