Text

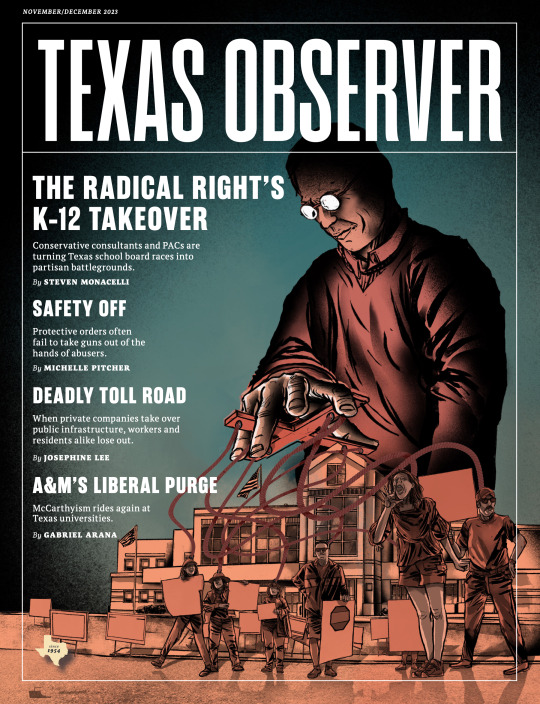

Texas Observer magazine comes out six times per year, and almost all of it ends up on our website, absolutely free. The Texas Observer has no paywalls, and depends on the support of our members!

Catch up on the March/April 2024 issue of Texas Observer magazine!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

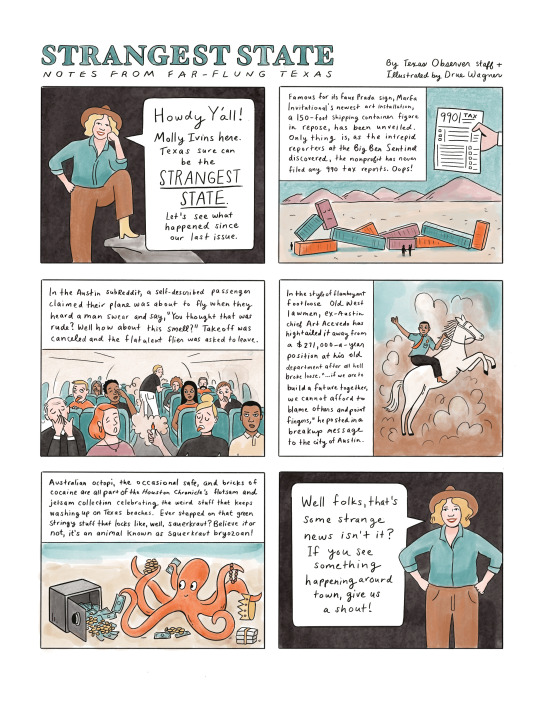

“Strangest State” from the March/April 2024 issue of our magazine.

By Texas Observer staff. Illustrated by Drue Wagner.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

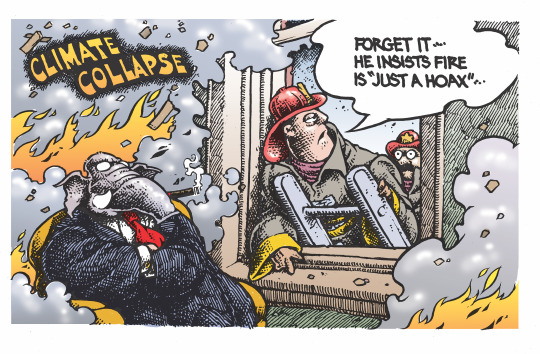

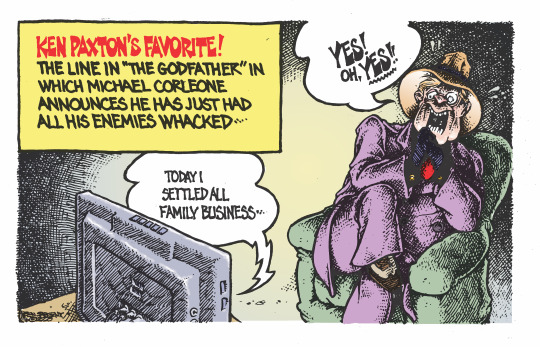

Loon Star State: Cult of the All-Powerful Orange Czar

From our magazine: The latest from Texas Observer political cartoonist Ben Sargent.

Read more from the March/April 2024 issue.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Hoax” by cartoonist Ben Sargent, in the January/February 2024 issue of Texas Observer magazine.

To see more political cartoons from Ben Sargent, visit our Loon Star State section, or find Observer political reporting here.

Read more from the Observer:

Drifting Toward Disaster—Our multipart series on the changing face of Texas waterways, under threat from pollution to overuse of aquifiers to the climate crisis.

Hella Hail Coming Down in Texas—Climate change is creating more extreme weather, in winter as well as in summer, according to Fall 2023 Reporting Fellow Paula Levihn-Coon.

Texas Workers, Congressman Launch ‘Thirst Strike’ for Heat Protections—On the other side of the aisle, Democrats are raising the alarm about the threat of heat on the workers who toil in it.

#political cartoon#comics#climate crisis#climate change#environment#republicans#waterways#weather#Texas

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

”Insects All Around Us” by Digital Edital Editor Kit O'Connell, originally published in the January/February 2024 issue of Texas Observer magazine:

Photography and additional reporting by Fall 2023 Reporting Fellow Paula Levihn-Coon.

The prey is already dying when the hunters arrive.

The sky is dark gray, the air thick with the threat of rain. But that hasn’t stopped over a dozen from gathering. They’re mostly, but not exclusively, older folks—frequently retirees with the ability to take a weekday morning off—and they’re armed with Digital SLR cameras and macro lenses.

Valerie Bugh crouches down over the squirming spots on the stone of the shady courtyard entrance to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, prodding at the poisoned insects. Bugh, a gray-haired local naturalist, isn’t responsible for the state of these southern yellowjackets (Vespula squamosa), but she’ll take advantage of it for a photo opportunity. Someone on staff at the center discovered their nest and sprayed them just before the bug hunters arrived, and the entire hive is trickling out from their hidden home in a low rock wall. Bugh warns me to keep my distance from the females, who have fatter-looking bodies with stingers compared to the longer, thinner males, which normally only leave the nest for mating purposes. As I take a step back, she fearlessly kneels by their wriggling bodies, picking the males up and focusing her camera on each in turn.

“I’m trying to find one that doesn’t look dead,” she said. Soon, she’d even manage to document the hive’s queen as it haplessly tried to flee the toxins—a rare catch, though a grim beginning for a weekly ritual that largely focuses on the living.

Katherine Daniels and David Cook, volunteers, take insect photos.

Bugh is the author of 10 short fold-out pamphlets with color photos, with titles like Spiders of Texas: A Guide to Common and Notable Species and Unusual Insects of Texas: Caddisflies, Mantides, Lacewings, Walking Sticks, & More. That’s just one of her jobs: She’s also second clarinet in the Austin Opera. She’s modest about these accomplishments when asked—Bugh is too busy searching for bugs to brag about herself.

Every Thursday morning from February through mid-December, Bugh and her team of volunteers in the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Fauna Project explore a winding path, gradually aiming to cover the entire grounds over the course of a year, in order to inspect more than 650 species of native plants in the gardens and the 50-plus species of oaks in the Texas Arboretum for their occupants.

With this diversity of native plants comes a diversity in insect population too. Allowing for a few pandemic-imposed breaks and schedule changes, Bugh has otherwise been doing this consistently since 2010, during which time she’s identified almost 3,000 species of insect including over 50 bees, 345 flies, and over 500 different beetles. It’s not unusual to find a new species to add to the garden’s known tiny inhabitant list every week.

As Bugh gets moving, other bug hunters follow her in a pack. One by one and in pairs they break off from documenting spiders and beetles found clinging to the brick walls around the entrance and offices of the center. A few volunteer birders are also on-site, but for the most part, they work independently and seem invisible compared to the cheerful, chattering bug hunters. The group also documents signs of larger animals, from mammals to amphibians, but their main focus is on these tiny crawling creatures, since bugs are the most plentiful fauna present both in this garden and worldwide.

Every Thursday from 2010 to the present, Valerie Bugh leads the Fauna Project at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, Texas.

The bug hunters move in a little cluster, calling out when they find something new for Bugh to examine. The salt marsh moth (Estigmene acrea) caterpillars are everywhere.

“If it’s a salt marsh, I don’t want to know about it,” declares Bugh dismissively, though with good humor. Their hairy bodies remind me of an asp, the caterpillar with a nasty sting. But they’re actually harmless to the touch. Bugh is just frustrated because there are too many of them. Unlike other caterpillars, the salt marsh moths will eat almost any plant, building its hairy cocoons all over.

“Every single plant is their host,” Bugh said.

By contrast, the Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae), another caterpillar present in the day’s fauna count, subsists almost entirely on passion flower vines.

Bugh’s disdain for the salt marsh moth doesn’t stop her from plucking one from the greenery and posing for a photo with it. She’s happy to show off and talk about her fauna friends, even the overly common ones. As she moves around, her tone becomes more of a graduate lecture in entomology, no doubt similar to the insect walks she sometimes leads around Austin. Her volunteers are here to hone their skills at macro photography, to learn from a preeminent local expert, and to expand their naturalist knowledge. Many are members of the Texas Master Naturalist program.

Valerie Bugh holds a salt marsh moth caterpillar (Estigmene acrea) in her hand.

But it’s a social occasion as much as anything, and the bug hunters talk among themselves around me, catching up on their lives. Two have just returned from African vacations and are excited to dish about all the great wildlife photos they got there, documenting large predatory wild beasts. But they seem just as eager to capture the living world’s small inhabitants in their lenses, too.

“It’s an insect safari,” said volunteer Katherine Baker, who told me she relished the challenge of macro photography after over a decade of experience in more general nature photography. She’s been helping count the fauna for about four years now, and always feels among kindred spirits here. But they all orbit around Valerie, returning to her for advice or an ID after wandering off.

Every Thursday for 13 years, naturalist and author Valerie Bugh, far left, has led volunteers in counting and photographing animals at the

wildflower center.

“Her knowledge surpasses everyone … she’s just amazing,” Baker said of Bugh.

The gray morning clouds are starting to burn off. As it warms up, the butterflies and others will begin to emerge from the foliage where they’re resting during the rainy, humid part of the day.

“Aha, here’s where the bumblebees are,” Bugh declares with delight as some are pointed out to her. “These are workers and look how docile they are, they’re barely moving.”

Even before the sun appears, I become aware of how the plants around us are full of life, more than first appears to the untuned eye. As I start looking at one insect, like the predatory leafhopper assassin bug (Zelus renardii), a leggy, long-bodied, hungry thing with a venomous proboscis, I spot another, smaller bug crawling along the same bit of wild grass. We allow ourselves to forget in our day-to-day lives, but insects are all over, constantly surrounding and outnumbering us.

Valerie Bugh shines a small LED light on an insect.

On the day we visited, the team spotted seven different kinds of grasshoppers, two types of katydids and one cricket. Hunters often spot the American bumblebee, Bombus pensylvanicus, which is thriving in Central Texas even as its numbers dwindle elsewhere. But lately, its Sonoran cousin (Bombus sonorus) has been showing up more and more in the bug counts.

“That doesn’t bode well for desertification,” Bugh told me. “We’ve had a lot of Western species moving in, birds too, which means the habitat is great for them and a little drier than we’re used to for everyone else.”

The naturalist bug hunters are strongly aware of the harm climate change has brought on our region, and there’s a bittersweet feeling to parts of the morning, a subtle sense that someday soon could be the last day one of these fauna appear in a count.

“The ecosystems are moving east, including tornado alley. It’s not great for the people in the way, and not great for us on the edge of deserts. Think of Austin without any trees. I really like trees,” Bugh says wistfully.

But most insects still spark joy when she spots them. As sure as falling leaves, the appearance of the scorpion flies (which are neither scorpions nor flies) represents the start of true Texas autumn, and they were just putting in their first appearances that Thursday in November.

Bugh can identify a great number of creatures on sight, but sometimes enlists help from collaborative internet forums and apps, or even, in one case, a book of Central American insects published in 1900.

Later, when I come home from the center, I pore over her very detailed homepage, which features a searchable spreadsheet of every creature identified by her team since 2010. I email Bugh to ask what changes she’s noticed over time.

“It is very hard to compare the past to the present since it is short term in geological time but very long term for humans,” she writes back. “Who can say what they’ve learned in over a decade? I bet it is a lot.”

#Austin#Texas#wildflowers#native plants#lady bird johnson#bugs#insects#photography#macro photography#wildlife#wildlife photography#fauna#science#entymology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Texas is the Strangest State.

From the January/February 2024 issue of our magazine.

0 notes

Text

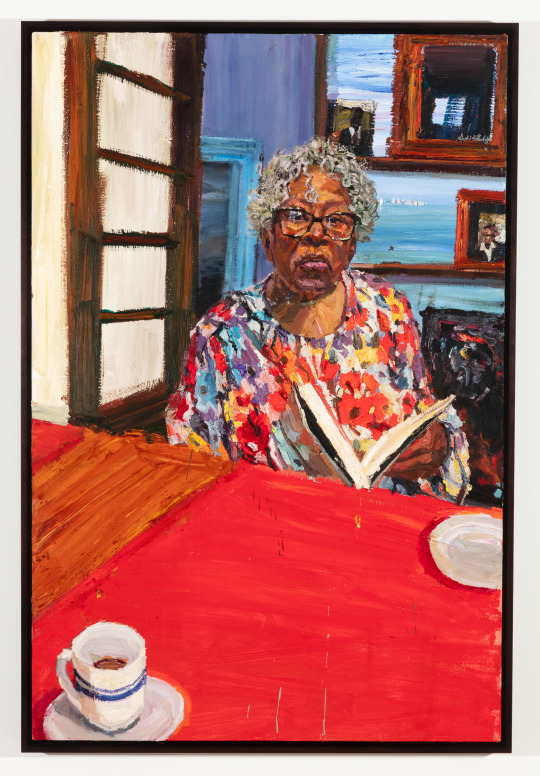

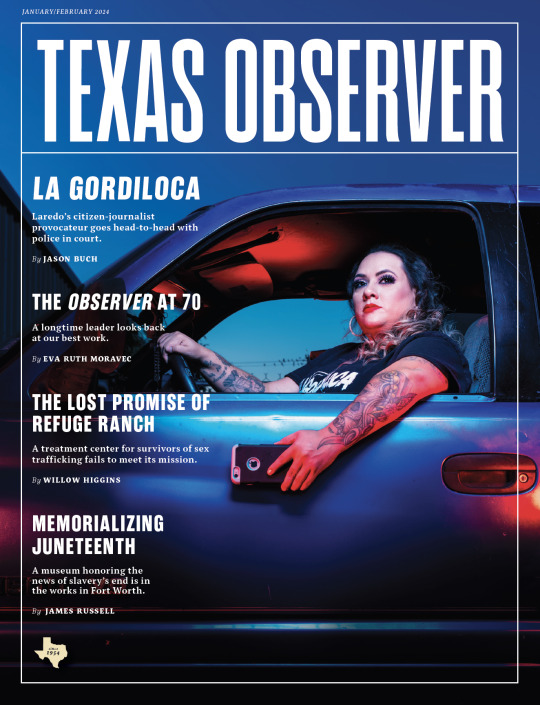

“The Long Road to a Juneteenth Museum” by James Rusell, from the January/February 2024 issue of Texas Observer Magazine:

(Museum renderings courtesy BIG)

When Fort Worth activist Opal Lee was invited in 2021 to stand alongside President Joe Biden as he signed the bill making Juneteenth a federal holiday, “I could’ve done a holy dance,” the 97-year-old told the Texas Observer recently. “But the kids said they didn’t want me twerking.”

Dancing—and twerking—aside, Lee is clearly used to ambitious projects. She’s often referred to as the grandmother of Juneteenth, mostly because of her 1,400-mile walk, Fort Worth to Washington, D.C., September 2016 to January 2017, seeking recognition for the day that has come to represent freedom for American Blacks. Although the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in 1863, slaves couldn’t be freed where the countryside was still under Confederate control. That ended in Texas on June 19, 1865, when Union troops arrived in Galveston and brought the news.

The latest project of Lee and her allies, to create a museum in Fort Worth honoring Juneteenth, is turning out to be equally ambitious. What began as a modest collection in a small house in the neighborhood where Lee grew up has become a key part of an effort to revitalize Fort Worth’s Historic Southside neighborhood. The most recent and much grander incarnation of the museum is due to open in 2025.

Along the way, the honors paid to Lee—a Nobel Peace Prize nomination, a painting of Lee for the National Portrait Gallery, and the Emmy Award-winning documentary Opal’s Walk for Freedom (2022)—have helped bring attention to that neighborhood, just as they did to the Juneteenth campaign. But tragedy and poverty have held hands there for a long time, and revitalization efforts sometimes find tough sledding.

Lee’s roots run deep into the soil of the Southside and into personal memories of another June 19. On that day in 1939, a mob of racists—about 500 people, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram—raided the house there that Lee, her parents, and two brothers, had recently moved into. The family promptly moved out.

A portrait of Opal Lee from the National Portrait Gallery (Courtesy of Talley Dunn Gallery)

The raid was traumatic. Lee told the Star-Telegram in 2003 that afterward her family was “homeless and then living in houses so ramshackle they were impossible to keep clean.” The experience led her to become first an advocate for affordable housing and later an activist regarding homelessness, hunger, and Juneteenth.

Eighty years after the raid, another violent incident a few blocks away would inspire a new generation of Southside activists.

Lee, a retired elementary school teacher and counselor in the Fort Worth school district, also spearheaded the rebuilding of the Metroplex Food Bank (now the Community Food Bank), founded the urban Opal’s Farm, and served on numerous local boards, including the Tarrant Black Historical and Genealogical Society.

Through all that time, she worked to draw attention to Juneteenth. “She was always teaching about Juneteenth” in middle school, said Sedrick Huckaby, the Fort Worth artist who painted Lee for the National Portrait Gallery. “She was always teaching about our heritage and about taking pride in who you are.” Allies like the late Rev. Dr. Ron Myers, a Mississippi doctor and minister, lobbied legislatures across the country and in 1997 helped pass a congressional joint resolution recognizing the holiday. Lee worked on building local support.

In 2014, on the 150th anniversary of Juneteenth, she asked friends and family to donate to a celebration of that, in lieu of buying presents on her birthday. A story in Fort Worth Weekly called her “part grandma, part General Patton” in leading the effort. Two years later, she was putting on her walking shoes for her own personal march on Washington. “If a lady in tennis shoes walked to Washington, D.C, maybe people would pay attention,” she said in her deep, raspy voice, recalling her motivations for the trek. It took another four years after her walk, but the national holiday happened.

Juneteenth has been celebrated by Black Americans for more than 100 years, including in Fort Worth. Texas was the first to designate it a state holiday, in 1980. Since 2020, 26 states, propelled by the murders of Black citizens George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police, have followed Texas’ lead, according to the Pew Research Center.

In Fort Worth, Lee and volunteer Don Williams had been working for years to gather artifacts related to local Black history and Juneteenth, including paintings by local Black artist Manet Harrison Fowler, scrapbooks chronicling local Juneteenth celebrations, and memorabilia from the locally filmed movie Miss Juneteenth. Lee inherited a house from her late husband Dale, a retired school district principal, and turned it into the first version of the Juneteenth museum. It housed the growing collection and hosted multiple Juneteenth events and, at one point, computer classes.

While the collection grew, the building, run by volunteers, was deteriorating. Like most public places, it closed in 2020 as COVID-19 spread. After the pandemic, it did not reopen, and the collection was moved out. Then early on the morning of January 11, 2023, it caught on fire. The remains were demolished to make way for the new museum.

Around 2019, Lee, granddaughter Dione Sims, and former Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce executive Jarred Howard had started talking about the possibility of a new Juneteenth Museum. They began buying land around the site of the old house. Howard long had a vision to help his old stomping grounds and wanted to both commemorate the holiday and spur economic development. Well acquainted with developers and architects from his Chamber days, he solicited requests for proposals for a building that could meet those goals. First, local architect Paul Dennehy designed a five-story building with a gallery, event space, and residences. In early 2020 it was pitched to neighborhood association leaders. Too tall, they said, and out of step with the neighborhood. In 2021, local architects Bennett Partners produced a plan for a playful mixed-use campus, estimated to cost about $30 million to build.

In 2022, a new plan, bigger in scope than Lee could have imagined two decades ago, was unveiled. The current proposal is for a 5-acre complex housing a National Juneteenth Museum, with a theater, restaurant, art galleries, and a “business incubator” space to spur Southside entrepreneurship, designed by the internationally renowned architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG). The price tag is an estimated $70 million. So far, the nonprofit National Juneteenth Museum, formed in 2020, has raised about $30 million of that, mostly from major donors and foundations, Lee said.

Douglass Alligood, a partner at BIG and the chief architect of the currently planned museum, got an earful during his field work on the project, including from Lee’s friends and supporters. In multiple visits, he met with Lee as well as neighborhood leaders. The conclusion: The museum had to represent the community and not be divorced from it.

“We were inspired by the neighborhood typology—the homes that feature historic gabled silhouettes and protruding porches, also known in context as a ‘shotgun’ house,” he said. “Neighborhood groups and community members found that, together, the BIG and KAI Enterprises [the local architecture firm] design teams demonstrate a deep understanding of the Juneteenth story and commitment to work with the local community to celebrate the holiday’s history and local culture of the Historic Southside.”

Eleven rectangular glass-clad building segments, with peaks and valleys of varying heights, will create a star-shaped courtyard in the middle. “The ‘new star,’ the nova star represents a new chapter for the African-Americans looking ahead towards a more just future,” Alligood said.

Fine, locals said, but what people there really need is a grocery store.

It was a cold morning in early October, and Patrice Jones needed help unloading herbs. She was in the courtyard of Connex, a new three-story business and retail complex about two blocks from the planned site of the museum. Jones and a group of volunteers, mostly in their 20s and 30s, from Southside Community Gardens, are planting their 79th and 80th backyard vegetable gardens in the neighborhood, she said proudly. It’s pick-up day for those who’ve already established gardens.

The initiative is part of the larger By Any Means 104 effort, named for the 76104 zip code, and co-founded by Jones in 2020. The group’s focus on local issues includes addressing the lack of fresh food in the area instead of waiting for a grocery store. Jones, a feisty advocate and former claims adjuster, has run it full time since 2021. If the city can’t get them a grocery store, she said, they’ll teach residents to grow their own food.

The Juneteenth Museum is important, Jones said, between handing out herbs and greeting volunteers. But in her circles, she said, people also ask, “Can we get a health clinic? Can we get a pharmacy?” And of course, “Can we get a grocery store?”

According to a 2018 University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center report, the 76104 zip code has the lowest life expectancy rate in Texas and a high maternal mortality rate. It’s also a victim of what Jones calls “food apartheid,” a term she prefers to “food desert,” an indicator of an area with little access to fresh foods. Desert implies it’s natural; apartheid, she said, is an intentional act. She blames city government and its white-dominated culture.

But hunger is not a sufficient reason for a grocery chain to decide where to open a store, even if it could be part of a historical complex.

Grocery store owners “use different metrics,” including population density, said Stacy Marshall, president of Southeast Fort Worth, Inc., an economic development group. “We can’t yet make a compelling case.” The area needs more housing, he said. “Build density—rooftops—and grocery stores come.”

Marshall is a force in bringing new development to the southeast part of the city, a large historically and ethnically diverse area that includes the Historic Southside.

Since he took the job a decade ago, “development has gone gangbusters,” he said. But development has also brought gentrification: “It’s so expensive to purchase dirt here and get a single-family home,” he said. One Dallas real estate firm put together a $70 million deal for a mixed-use development in the area, but it has stalled.

The Juneteenth museum site is within the Evans-Rosedale urban village, a city designation focused on bringing investment to the area. It’s seeing an uptick in interest from developers, but nowhere near what’s been promised by local officials.

“There have been attempts in the past. There’s the Evans Avenue Plaza, but most people don’t know about it,” said Bob Ray Sanders, communications director for the Fort Worth Black Chamber of Commerce. The plaza, also part of the Evans-Rosedale village, is meant to be a community gathering space and includes a new library. About a mile away is the Hazel Harvey Peace Center for Neighborhoods, which houses numerous city offices.

Many of the neighborhood’s nagging problems date to the mid-20th century, when integration meant, ironically, the loss of many black-owned businesses, while highway construction—as it did in many American cities—cut off Fort Worth’s Black community from downtown and wealthier neighborhoods. “By doing that, people on the Westside [turned] a blind eye to people on the Eastside,” Sanders said.

Housing construction seems to be picking up, mostly on an infill basis. But while developers are buying homes, Marshall said, they are mostly sitting on them and waiting until they can get higher prices.

Longtime assistant city manager Fernando Costa said development work in historic urban districts presents more challenges than creating new neighborhoods from pastureland. Beyond the physical complications of older infrastructure, historic preservation concerns and, often, environmental problems left over from earlier development, Costa said, such projects “require getting existing neighborhood involvement.”

There’s also the issue of crime. According to the Fort Worth Police Department, nearly 560 crimes were reported in the 76104 zip code between mid-May and late November 2023. Assault, larceny, drug and alcohol violations, and vehicle break-ins made up more than three-quarters of the reports. That’s compared to 165 in the same time period in the mostly-white, wealthy 76109 zip code in West Fort Worth.

In the early morning of October 12, 2019, white police officer Aaron Dean, responding to a welfare check at the house, killed 28-year Black woman Atatiana Jefferson, who was playing video games with her nephew. Dean was later found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Jefferson’s murder lit a fire under a younger generation of activists who aren’t waiting for change, such as Jones, who also worked to get police accountability in response to the murder, and Angela Mack, whose doctoral thesis is about Jefferson and the neighborhood.

“I’m a good, ol’ fashioned Funkytown Black nerd,” said Mack, an instructor in the comparative race and ethnic studies department at Texas Christian University, where she received her doctorate in English rhetoric.

After Jefferson’s murder, Mack changed her thesis topic to address that tragedy. She saw that, between her mother and the national media, two different stories were being told.

“When we’re thinking about the Southside, we think about Fairmount and the Medical District in terms of revitalization. But when you cross the highway, you’re in an area with crime and poverty,” she said, drinking a latte at Black Coffee, one of the few coffee shops in the area. “When people [look] at the community, people are looking at what’s not here. It’s a deficit model of communication instead of seeing the good that’s here.

“I’m not anti-development,” she said, but economic development shouldn’t be the museum’s purpose.

“When you’re building something, it should not be [a question of] how many people we employ, but how does it help define the Southside? The development will come. I’m concerned about who controls the narrative,” she said. “The main focus should be how does this speak about our history and heritage.”

Jones also worries that history will be lost. She’s afraid that rising property values will push out poor people.

Sims has heard those concerns before. Property taxes go up with any new development, she said. And everyone’s going to complain, even if they want change.

When the museum opens in 2025, Lee just wants to make sure she’s there to see it.

“I’m looking forward to it,” she said. She’d be 99. “I hope I’m still here.”

#black history#Black History Month#Texas#texas history#fort worth#north texas#juneteenth#museum#museums

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Above: A lightning strike crackles at the edge of a storm cloud above State Route 80 in Arizona.

Sergio Chapa’s photos and a portion of this text also appear in Frontera: A Journey Across the US-Mexico Border and are reprinted with permission from TCU Press. This excerpt originally appeared in the January/February 2024 issue of Texas Observer magazine.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera and I met when she was a political science professor at the University of Texas at Brownsville. She was studying drug cartel violence in the war-torn Mexican border state of Tamaulipas, and I was covering the same topic as a journalist for KGBT-TV in the Rio Grande Valley. We bonded over our work—and our mutual desire to “see the entire border.”

We made our first border-to-border journey together in June 2013, stopping at each crossing between Brownsville and El Paso with jaunts into Mexico. And we kept on traveling together for much of the next decade pursuing a dream that became our book, Frontera: A Journey Across the US-Mexico Border (TCU Press, January 2024).

In our first days on the road in June 2013, we’d seen closed businesses and other bleak effects of cartel violence on Mexican border towns, before rolling into Big Bend National Park. We had heard about the park’s beauty but marveled over its mountains, colorful canyons, and unique micro-ecosystems.

While driving along a rocky and mountainous stretch of the park, the Bible verse of Luke 19:40 sprang to mind, “I tell you, if they were to keep silent, the stones would cry out.” The original verse had a distinct meaning, but for us, it meant that if we failed to acknowledge the beauty before our eyes, the rocks themselves might literally protest. After a few minutes, we shrugged it off as maybe stupor over the 90-degree-Fahrenheit day or exhaustion from the eight-hour drive.

But after settling into our hotel in Terlingua, we joined other guests for dinner and live music on a rooftop patio where monsoon rains and lightning strikes could be seen in the distance. A couple of beers later, a solo guitarist sang these lyrics: “And the rocks will cry out.” We looked at each other wide-eyed in that moment of serendipity. After his set ended, we spoke to the musician, who told a story similar to our own.

That night, we sat outside until millions of stars appeared, tracing the Milky Way above us. It was one of what we called momentos mágicos along the frontera.

Despite the negative political rhetoric, the U.S.-Mexico border is a beautiful place, home to welcoming and warm people. It is also a land of contrast—austere landscapes and lush oases; thunderstorms and rainbows; robust industries and ghost towns; great wealth and aching poverty. The residents, known as borderlanders or fronterizos, are among the poorest in the United States. Those in Mexico inhabit cities that can be very unsafe. Nonetheless, these citizens often open their homes and pocketbooks to help stranded tourists as well as asylum seekers from Central America, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia.

The Fiestas Mexicanas Parade in Matamoros, Tamaulipas draws participants from both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Over the last decade, we have traveled different segments and made three different trips along the whole frontier, from Brownsville, Texas/Matamoros, Tamaulipas, to San Diego, California/Tijuana, Baja California. When we started, we were fronterizos, living and working in the Rio Grande Valley region. We still understand border dynamics, though we’ve both moved; I’m now a freelance writer and energy industry analyst in Houston and Correa-Cabrera teaches at a university in Fairfax, Virginia.

The border region is home to billions of dollars in trade and beautiful landscapes, including beaches, dense subtropical forests, deserts, and mountains. Its sprawling cities offer disparities of their own, with industrial parks and fashionable shopping malls, as well as immaculate country clubs and neglected colonias, where some earn a meager living scavenging recyclable items from landfills.

Its international boundaries were established by wars but people with family, friends, and businesses on both sides have often ignored dividing lines. Far from the capitals of Washington, D.C. and Mexico City, they created their own culture, which is distinct from their parent cultures. The result is a mixture where “Spanglish” has become its own language and where the music, food, binational economy, and resilience of the people reflect this bicultural blend.

Many books have been written about the U.S.-Mexico border, but none is like ours. Frontera offers a glimpse into every crossing community in all U.S.-Mexico border states. It includes notes and reflections by experts, academics and others about the border and about how the pandemic has changed places we visited—and thought we knew so well.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the partial closure of the U.S.-Mexico border transformed the region’s face and socioeconomic configuration. Although we do not know what the borderlands will look like in the future, we do know the border and fronterizos will quickly adapt.

Our last trip to complete this book took place in July 2021.

There was no cloud in the sky on that 100-degree day as we drove Mexico’s Federal Highway 3 between the resort town of Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, and the border city of San Luis Río Colorado.

Neither of us had ever before visited this desolate desert highway along the Gulf of California, but we’d been warned: There is no cell phone service on the remote road, where numerous robberies had taken place and suspects had left victims stranded.

We were traveling in a pack of cars, so things seemed safe at first. I dodged dozens of potholes and drove around dunes slowly creeping over the highway.

We were amazed by views that few Americans ever see: Dunes, crystal blue water, and rugged canyons stretched out beside the highway. The finish line that day was supposed to be dinner with friends in Tijuana.

But then, I couldn’t avoid a deep pothole in time. The impact sent my front passenger side tire flying into sand. Luckily, I was able to stop the car without any other damage. I saw that the side of the tire had split in half. It was unbearably hot and, as predicted, we had no signal.

That’s when an old, beat-up car pulled up behind us. We couldn’t see the driver inside, and suddenly, those warnings flooded back. Panic briefly overcame us until we saw a man get out of the car with his wife and 6-year-old son.

He didn’t waste any time. He had a spare tire, which wasn’t really the right size, but we somehow made it fit. He waited until we were sure the tire would work and refused any money. We made it to Yuma, Arizona where we got a proper-sized tire. We didn’t get that man’s name or number, but he saved our lives. He was our “border angel.”

We are forever grateful to that anonymous and humbleTGood Samaritan, who helped us tell the true story of the border. I still keep the spare tire he gave us in my trunk, ready for the next person who needs it.

Don’t miss another issue, become a member today.

#travel#us mexico border#border#Mexico#Texas#border town#photography#documentary photography#brownsvilletx#matamoros#San Diego#books#tijuana

0 notes

Text

“Will Texas Cities Stay Silent on Gaza?” by Gus Bova, from the Texas Observer:

Last Thursday, a stream of Austinites poured into their city hall and packed the council meeting chamber—some carrying signs, some with hands painted red, and many sporting black-and-white keffiyehs, headscarves that serve as international symbols of solidarity with the Palestinian struggle.

The activists were there to push the city council to pass a resolution calling for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip. But since no such item was on the agenda that day, they’d simply booked all the slots in an open public comment period to make their case.

“I am a Jewish mother; I am also the descendant of survivors of the Holocaust in Germany and the pogroms in Russia. I have been devastated every day watching this genocide unfold,” said Abigail Mallick, one of a series of Jewish speakers who addressed the council that day to oppose Israel’s recent military actions. “We must pass a ceasefire resolution. … We must join the growing chorus of voices saying ‘never again’—‘never again’ for anyone.”

The testimony was part of a monthslong effort in Austin and other cities across Texas and the country to get local governments to weigh in on the tragedy unfolding across the world in Gaza, the 140-square-mile slice of Palestinian territory that abuts the Egyptian border and the Mediterranean Sea. Since October 7, when Hamas, the Palestinian militant group that governs Gaza, executed a horrific attack in southern Israel that left 1,200 dead and more than 200 kidnapped, Israel has retaliated by unleashing Hell on Earth for 2.2 million Gazans. As of late January, about 25,000 Palestinians have been killed with the majority being women and children, per the Gaza Health Ministry. A quarter of Gazans are starving, and nearly the entire population is displaced.

South Africa has brought claims of genocide against Israel at the International Court of Justice; Israel denies the charges. Many scholars have warned for months of a possible genocide unfolding, though Israel’s defenders including the U.S. State Department dispute the claim.

Both Arab and Palestinian Americans are undercounted by the U.S. Census, according to the Arab American Institute, but Texas ranks among the top five states for both communities. The state’s biggest urban areas, especially Harris County and the Metroplex, all boast significant populations.

The Texas Democratic Party was the first among all states to officially call for a ceasefire in Gaza; five of 13 Lone Star Dems in the U.S. House have also done so, in addition to the AFL-CIO central labor councils in San Antonio and Austin. Massive protests have been held across Texas cities, including one in November that was likely the largest demonstration at the state Capitol since the 2017 Women’s March. Nationwide, at least a couple dozen cities have passed ceasefire resolutions, including San Francisco, Atlanta, and Detroit. But, so far, Texas activists are running into brick walls with their municipal representatives as council members either stay silent or argue that endorsing a ceasefire would inflame divisions in their cities or that the issue is simply not a local matter.

At the Austin meeting last week, Council member Chito Vela told the pro-Palestine crowd that he personally supported a ceasefire and had signed an open letter to that effect. “However, I do not want this council to become embroiled in foreign policy matters,” he clarified. “These are far beyond our purview as a local government, and we have too many critical local issues that demand our attention.”

In November, Austin’s Human Rights Commission urged the city council to call for a ceasefire. Three council members issued a joint statement in December expressing their support, and activists believe these three would back a formal resolution. With a fourth member, they could force a vote, but—even in Texas’ most left-wing city—sufficient support remains elusive.

“Our city always was known for standing for human rights and for progressive values,” said Hatem Natsheh, a member of the recently formed Austin for Palestine Coalition and longtime local activist who was born in Palestine’s West Bank. “We need our leaders to stand with us and [against] these horrific crimes that happen to our community.”

Natsheh noted that the council has weighed in on foreign policy before with resolutions condemning ex-President Donald Trump’s Muslim ban and the 2003 Iraq invasion. He also observed that Mayor Kirk Watson, whose office did not respond to a request for comment, spoke at a pro-Israel event shortly after the October 7 attack. “We know that the City of Austin has no power over international issues, but we are not asking because of that,” Natsheh said. “We’re asking them to take a moral stand for humanity.”

Just down I-35, in San Antonio, pro-Palestine activists nearly secured a ceasefire vote earlier this month before a council member reversed course.

With three members supporting, which is enough to convene a special meeting in San Antonio, the Alamo City council was set to vote on a ceasefire resolution in either January or February. But earlier this month, Council Member Manny Pelaez withdrew his support, saying, “It became evident that this was causing more pain and anxiety than was originally intended.” Another council member, Jalen McKee-Rodriguez, called Pelaez’s decision “one of the weakest moves I’ve ever seen from any councilmember ever.”

In late December, a group of Jewish leaders in San Antonio had written city council arguing that the resolution, “while well-intentioned, is morally wrong and will further endanger members of the local Jewish community.” Following Pelaez’s reversal, Mayor Ron Nirenberg penned a memo stating the special meeting was scrapped. In it, Nirenberg suggested the vote would have “exacerbate[d] trauma,” adding that “Wading into a complex and volatile international environment with an incomplete understanding could prove to be reckless.”

The ceasefire push has been led in part by San Antonio for Justice in Palestine (SAJP), a Palestinian-led group that existed prior to October 7 but has been revitalized in the last few months. The group works alongside others including the local chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, which has coalesced pro-Palestine Jews across the country. “The call is coming straight from Gaza, straight from Palestine … that we need to do everything within our power to make calls for a ceasefire,” said Sara Masoud, a Palestinian SAJP core member and health science professor with family in the West Bank. She noted that the council in 2022 passed a resolution calling for a ceasefire in Ukraine and also contradicted Nirenberg, saying a “call for a ceasefire actually reduces trauma because it speaks on behalf of peace.”

Masoud said her group and allies will keep working to find a third supporter to replace Pelaez.

In Dallas, council members approved a resolution on October 11 stating that the city “stands with Israel in its fight against Hamas.” Since then, as the death toll in Gaza has soared, Dallasites have repeatedly turned out to push the body to consider a ceasefire resolution. “It’s a city issue in that countless Palestinians here in Dallas have been affected by it, have lost family members,” said Sumayyah El-Heet, a Palestinian organizer with the Dallas chapter of the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM). El-Heet said she knew of Dallasites who are mourning dozens of family members killed in Gaza.

Dallas Council member Adam Bazaldua has authored a ceasefire resolution. Depending on the procedure used, Bazaldua told the Texas Observer, he needs either two or four additional supporters to trigger a vote. He said he has little patience for the argument that the matter is not a local issue or that it would distract from municipal business.

“I personally cannot stand that pushback on any particular item,” Bazaldua said, “because if we were elected and not expected to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time, then I don’t know why the hell we were elected.”

Down I-45, Houston has seen months of large pro-Palestine demonstrations and other events. The Bayou City has one of the largest Arab-American populations in the nation. While some council members have voiced support for a ceasefire, ex-Mayor Sylvester Turner—who left office at the beginning of this month—has said Houston City Council simply does not do resolutions of this sort. In an email, spokesperson Mary Benton told the Observer that Houston “does not have a history of issuing resolutions regarding global conflicts” or other issues beyond city administrative business, though she said she hadn’t yet discussed the matter with now-Mayor John Whitmire.

“Houston holds one of the largest Palestinian and Arab communities in the country right now; we have Houstonians who were trapped in Gaza for months,” said Fouad Salah, an organizer with the Houston chapter of PYM, which has been pushing city council unsuccessfully to take a stand on the issue. “We have Houstonians—I mean, myself, I have family, God rest their souls—who have been murdered in Gaza. … To be clear, a lack of calling for a ceasefire is an endorsement of the genocide of our people.”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before I Was a Gazan by Naomi Shihab Nye

I was a boy

and my homework was missing,

paper with numbers on it,

stacked and lined,

I was looking for my piece of paper,

proud of this plus that, then multiplied,

not remembering if I had left it

on the table after showing to my uncle

or the shelf after combing my hair

but it was still somewhere

and I was going to find it and turn it in,

make my teacher happy,

make her say my name to the whole class,

before everything got subtracted

in a minute

even my uncle

even my teacher

even the best math student and his baby sister

who couldn’t talk yet.

And now I would do anything

for a problem I could solve.

“Life As a Palestinian Poet,” an interview with Naomi Shihab Nye, former poetry editor for the Texas Observer, with Roy W. Howard investigative reporting fellow Francesca D'Annunzio:

Naomi Shihab Nye is the Texas Observer’s poetry editor emeritus. She is Palestinian-American and grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and San Antonio. She frequently visited family in Palestine throughout her lifetime, including as a child. Amid Israel’s ongoing bombardment of Gaza, the Observer asked her about how growing up Palestinian influenced her writing.

What attracted you to poetry?

That was a lifetime, instinctive connection.

I loved the ways poetry worked on the page and in our brains. I loved the spaciousness about poetry—the space around the lines and room for your own thinking. I love the variety of voices.

By the time I was in second grade, I already felt like poetry was my land. I was writing my own poems from the age of six, and when I was seven, I started sending them to children’s magazines. It was a world that I entered into out of pleasure. It helped me think, and it gave me space to be in that felt meaningful.

There’s a rich history and legacy of Palestinian poets like the late Mahmoud Darwish and Mosab Abu Taha from Gaza. Are there any Palestinian poets who inspire your work?

My father would read [the works of poet Mahmoud] Darwish to me when I was a child and translate it because, in those days, there were not many translations of him. My father would read other poetry and translate it for me, and I just loved it. I loved everything about it: the metaphors, the passion, the care, the tenderness, the flowing quality of the lines. I eventually met Darwish, and he would ask me to read his poems in English; he didn’t like to read his poems in English at all. He read in Arabic, and just getting to be with him was such a landmark in my lifetime’s experience.

I had a chance to be with [Palestinian poets] Fadwa Tuqan or Samih al-Qasim, Taha Muhammad Ali, whom I adored—or just so many people who are now not available to us in the flesh, only through their words.

I felt them as a wellspring of the spirit of Palestine, and the love and the care for Palestine—that is something that the media often finds easy to overlook. It’s just so insulting—versus the poetry which is so respectful, passionate, loving, and nostalgic.

One of your 2014 poems, “Before I Was A Gazan,” reads like it was written this year. What’s the backstory?

It’s not a new poem. It’s 10 years old. At that time, there were some literacy programs out of Gaza that were inviting me and some other writers I know to be with the children, be with the students, and talk about writing and story, and why we need story, and why we need to believe in our own voices. Shortly after one of my sessions with these beautiful, beautiful kids who never ever complained about anything, there was a horrible, genocidal bombing of Gaza. … I just kept picturing these kids and thinking about their names, and what had happened to them, how many were still living, were any still living, were any of them killed, and I kept trying to get through to their teacher and find out if they were. That poem was from a horrible sleepless night.

They were just human beings. They were kids; they were proud—just like the boy in the poem is proud of his math homework. I was just thinking how horrific it is that children have to suffer these disasters, and I felt like I needed to write something in their honor. That’s how that poem came to be—but the weird part about that poem is, it’s not obsolete; it’s continued to be relevant all these years.

As poets, our minds reel and give us images. I just kept thinking, What would it be like to be a child who goes off to school or loses your homework, or something so pedestrian? And then your whole house disappears before you can even get home.

Earlier, you called going to Palestine a “deep experience,” and I noticed in some of your poems, there are these classical symbols and themes about Palestine, like olive trees and figs. How does being Palestinian-American influence your writing?

Oh, that’s so beautiful. It’s just everywhere—it’s my texture; it’s my material; it’s my body of knowledge; it’s my dream field.

I think we all pull from the world right around us. Palestine, for me, was like the soul place. My father never wanted to stay gone from it long. He always dreamed of going back. He wanted to be on his own land. He wanted to treasure and be in that community that he loved so much. He wanted to die there.

For me, as a writer, just to have this fabric, this gorgeous fabric like the Palestinian tatreez [traditional Palestinian embroidery], the stitchery, the tiny threads of color traveling through my whole life has been the most important thing to me.

Palestine has been for so many people an unresolved dream of gravity and beauty. It’s people from Brooklyn who currently have my father’s old home in Jerusalem or did the last time I was there. There’s that sense of unresolvedness when people are haunted by something that’s not right.

Palestinians are all haunted. We’re haunted by what used to be, what could have been, what we dream could be, what we would prefer for all the people who are living there right in the heart of it—and have everything at stake. Everything.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

January/February 2024 issue out now!

Check your email: Our members just received the digital edition of our January/February 2024 issue. Print editions are arriving in mailboxes and at select newsstands soon!

Don't miss another issue, become a member today.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

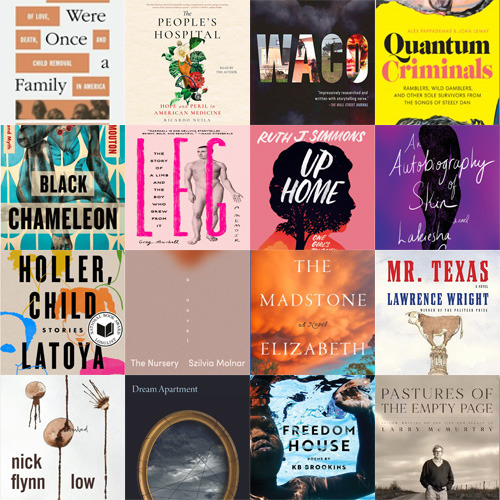

“The Texas Observer’s 2023 Must-Read Lone Star Books” by Senior Editor Lise Olsen, with help from Susan Post of Austin's Bookwoman:

Despite a disturbing rise in book bans, Texas is, against all odds, becoming more and more of a literary hub with authors winning accolades, indie bookstores popping up from Galveston Island to El Paso, and ban-busting librarians and other book-lovers throwing festivals. So as you ponder gifts this holiday season or consider what to read by the fire or by the pool (who can say in December?), pick some Lone Star lit.

Here’s a list of #MustRead 2023 books by Texans or about Texas compiled by the Observer staff with help from Susan Post of Austin’s independent Bookwoman. (Several talented Texans also made best book lists in Slate magazine, The New Yorker, and NPR’s Books We Love.)

NONFICTION

We Were Once a Family: A Story of Love, Death, and Child Removal in America by Dallas journalist Roxanna Asgarian (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) is a dramatic takedown of the Texas foster care and family court system. It’s both a compelling narrative and an investigative tour de force.

The People’s Hospital: Hope and Peril in American Medicine (Simon & Schuster) by Ricardo Nuila, a Houston physician and author, is an eye-opening and surprisingly optimistic read. Nuila delves deeply into what’s wrong with modern medicine by painting rich portraits of the patients he’s treated (and befriended) while working at Harris County’s Ben Taub Hospital, which offers free or low-cost—yet high-quality—care against all odds. Each of them had been forced into impossible positions and suffered additional trauma from obstacles and gaps in insurance, corporate medicine, and Big Pharma.

Waco: David Koresh, the Branch Davidians and a Legacy of Rage (Simon & Schuster) by Fort Worth journalist Jeff Guinn is one of two books that mark the 30th anniversary of the standoff between the Branch Davidians and federal agents that ended with 86 deaths. (The other is Waco Rising by Kevin Cook.) Both authors recount how the 1993 tragedy shaped other extremist leaders in America—and still influences separatist movements today.

Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan (University of Texas Press) by Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay has been described as the quintessential Steely Dan book. As part of the project, LeMay, a native Houstonian, created 109 whimsical portraits of characters that sprang from the musicians’ lyrics and legends. In a review, fellow artist Melissa Messer wrote: “Looking at Joan’s oeuvre makes me feel tipsy, or like I’ve drunk Wonka’s Fizzy Lifting Drink and I’m swimming through the air after her, searching for the same vision.”

Memoir

Black Cameleon: Memory, Womanhood and Myth(Macmillan) by Debra D.E.E.P. Mouton, the former Houston poet Laureate, shares lyrical memories of her own life mixed with ample asides on Black culture and family lore. Her storylines sink deeply into a dream world, and yet readers emerge without forgetting her deeper messages.

Leg: The Story of a Limb and a Boy Who Grew from It (Abrams Books) by Greg Marshall of Austin has been described as “a hilarious and poignant memoir grappling with family, disability, and coming of age in two closets—as a gay man and as a man living with cerebral palsy.” NPR’s Scott Simon, who interviewed Marshall, described the memoir as “intimate, and I mean that in all ways—insightful and often laugh-out-loud funny.”

Up Home: One Girl’s Journey (Penguin Random House) by Ruth J. Simmonsis a powerful memoir from the Grapeland native who became the president of Brown University and thus, the first Black president of an Ivy League institution. Simmons begins by sharing stories about her parents, who were sharecroppers, and about her life as one of 12 children growing up in a tiny Texas town during the Jim Crow era. For her, the classroom became “a place of brilliant light unlike any our homes afforded.” (Simmons’s other academic credentials include being the former president of Smith College; president of Prairie View A&M University, Texas’s oldest HBCU; and the former vice provost of Princeton.)

Novels and Short Stories

An Autobiography of Skin(Penguin Random House) by Lakiesha Carr weaves together three powerful narratives all featuring Black women from Texas. Carr, a journalist originally from East Texas, plumbs the depths of each character’s struggles, sharing tales of gambling, lost love, abuse, and the power of women to overcome.

Holler, Child (Penguin Random House), a new short story collection from Latoya Watkins, was long-listed for the National Book Award. Her eleven tales press “at the bruises of guilt, love, and circumstance,” as the cover description promises, and introduce West Texas-inspired characters irrevocably shaped by place.

The Nursery (Pantheon Books) by Szilvia Molnar—a surprisingly honest, anatomically accurate (and unsettling) novel about new motherhood—begins: “I used to be a translator and now I am a milk bar.” It’s a riveting and original debut by Molnar, who is originally from Budapest, was raised in Sweden, and now lives in Austin.

Two legendary Austin writers weighed in with new novels on our tall stack of Texas goodreads: The Madstone (Little, Brown and Company) by Elizabeth Crook, the 2023 Texas Writer Award winner, and Mr. Texas, a fictional send-up of Texas politics by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Lawrence Wright.

Poetry

Bookwoman’s Susan Post, who contributed titles to our list, also recommends filling your holiday shelves with poetry by and about Texans:

Dream Apartment (Copper Canyon Press) by Lisa Olstein;

Low (Gray Wolf Press) by Nick Flynn;

Freedom House by KB Brookins (published by Dallas’ Deep Vellum Bookstore & Publishing Co.)

Essays

Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry (University of Texas Press) edited by George Getchow, contains essays from a who’s who list of Texas writers about Larry McMurtry’s influence on Texas culture and their lives. It includes an array of reflections on history and the writing process as well as anecdotes about McMurtry’s off-beat and innovative life.

To Name the Bigger Lie (Simon & Schuster) by Sarah Viren, an ex-Texan who now teaches creative writing at Arizona State University, (excerpted in Lithub) includes reflections on Viren’s experiences (and misadventures) as an “out” academic and writer in states like Florida, Texas, and Arizona. As she dryly notes, “Critiques of the personal essay, and by extension memoir, are often gendered—not to mention classist and racist and homophobic.”

Can you help us survive, and thrive into our 70th year during this challenging time for the journalism industry?

Right now, all donations to the Texas Observer will be matched. Donate now!

#books#feminism#feminist books#Texas#fiction#nonfiction#poetry#essay#southern fiction#LGBTQIA#gay fiction

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

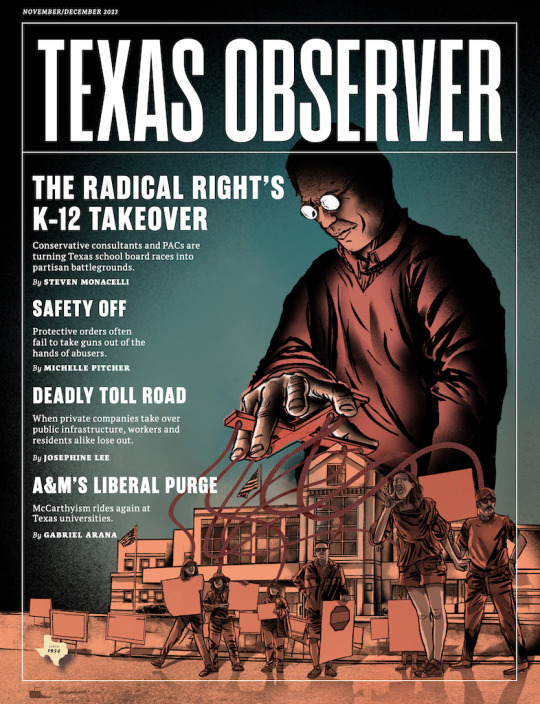

“From There to Here” by Ann Graham, published in the November/December 2023 issue of Texas Observer magazine:

A silhouette, stationed at his Dallas valet stand

awaiting the healthy, the wealthy, the privileged, the

favored. Hugo fled the warfare, mourning the wife

he couldn’t save. Inhales ashes to ashes, exhales.

Breeze beckons dusty grasses and limbs. Inhales

burnt engine oil, exhales. Leather wingtips and

cashmere emerge from a polished Tesla. Inhales

VegaFina cigar, peated Scotch, starched linen,

exhales. Woman steering silver Mercedes presents

herself. Inhales lemon peony, exhales. A limousine

slides to a somber stop. Stilettos, softly knobbed

knees, and a coiled braid materialize. Inhales

Shalimar, merlot, raw perspiration, exhales. Rattling

his reveries as if Bianca’s alive, her nasopharyngeal

carcinoma dead instead. Hugo, the silhouette,

replants his stance.

Ann Graham’s writings have been published in various journals. A retired visual resources curator, she lives in Denton.

To submit a poem, please send an email, with the poem as an attachment, to [email protected]. We are looking for previously unpublished works of no more than 30 lines, by Texas poets who have not been published by the Observer in the last two years. Pay is $100 on publication. Poems will be chosen by our guest editors.

Get our magazine, six times a year, starting at just about $3 per month. Become a member today!

1 note

·

View note

Text

“A Paris to Marfa March for Reproductive Rights” by Gayle Reaves, from the November/December issue of Texas Observer magazine:

Above: Louise Culbertson, 15, organized protests and rallies all over Texas on behalf of reproductive rights.

Louise Culbertson’s passion for political activism started when she heard about the murders of 17 students at a Parkland, Florida, school in 2018. With her mother’s help, she organized a demonstration in support of stronger gun laws in her hometown of Marfa. About 200 people showed up.

Culbertson was 10 years old at the time. She was proud to put Marfa on the map of places that had marched against gun violence, a list kept by March for Our Lives, the national organization of young people formed in the wake of Parkland to push back against the epidemic of shootings.

It was something Marfa needed, Culbertson said. The fear of a mass shooting at her own school was real. The shooting at a Santa Fe, Texas, school had happened the same year as Parkland. Four years later, Uvalde’s tragedy would reinforce the bitter, tragic lesson. What happened at Parkland and the other schools “really, really scared me,” she said.

Fast-forward to summer of this year, and Culbertson, now 15, was organizing protests and rallies all over Texas, this time in support of reproductive rights. And doing it from Paris, France. Anger at the reversal of Roe v. Wade had turned up her activism by a couple of notches. Thanks to her mother’s French background, Culbertson and her brother had been able to enroll in school in Paris two years earlier. But Culbertson was coming home to Texas for the summer with a mission.

She started planning in April, and in May got in touch with a nonprofit called Deeds Not Words (founded by former state senator and gubernatorial candidate Wendy Davis) that helps young women build a stronger voice in politics. With their mentoring, Culbertson put together protest events in five cities. Amid Texas’ mind-numbing summer heat, she and her mom, Valerie Breuvart, drove from Austin to Houston, then to Dallas, El Paso, and home to Marfa. In Austin, only a handful of young people showed. In Houston, Dallas, and El Paso, Culbertson said, the turnout was about 20 to 30, from young teenagers to adults. Back home in Marfa, her event drew about 50 fellow protesters. In the other cities, Culbertson said, the events were in one place and featured speakers and people chanting and holding up signs. But in Marfa, she said, “We actually marched.”

“I loved it,” Culbertson said. “I definitely learned a lot. … We had great speakers.” And of course, she got to meet people all over the state and immerse herself in politics.

Where does her determination and interest in politics come from? Her father, Don Culbertson, is a physician’s assistant and her mother a teacher of art history. For more than a decade, they have owned and run a medical clinic in Marfa, with Breuvart working on the business side. “I was raised with my parents talking a lot about politics,” Culbertson said. She described them as “strong Democrats” who took her to polling places to show her how elections worked. “All my passion for politics comes from my parents cheering me along.”

The couple shared their daughter’s fears about gun violence and her concerns about the quality of the schooling that she and her brother would get in Texas. In 2021, they took a year’s sabbatical and went to France.

“We live here [in Marfa]; we have a business, our home. Louise was born on the living room floor here,” Don Culbertson said. But his wife’s background gave them the “opportunity to get a kick-ass education” in Paris for their kids. “And so we’re doing that. We’re so excited,” he said. For now, he and his wife return to Texas for a few weeks several times a year. While in France, Don Culbertson participates in the clinic via telemedicine. The whole family comes home in the summer.

Louise Culbertson said that the language instruction she’s getting in Paris is the best part. The schools she would be going to in Texas offer little in the way of foreign language programs, she said, whereas in Paris, “half of my courses are in English, half in French, and you have to take a third language.” A small city in Texas—even if it’s Marfa—can’t offer the social life that is available in Paris, and then there are, of course, the opportunities for activism.

In Paris, Culbertson is active in a group called Democrats Abroad France doing things like helping register Americans to vote back home. Her brother Victor, 18, is “even more happy than I was to move to Paris.” She called him a “classic teenager … having fun.”

Her activism probably wouldn’t go over as well in other parts of conservative rural Texas. But Marfa and Presidio County tend to be a world of their own—very oriented toward the arts and politically, as she said, “one blue county in a whole pool of red.”

Culbertson “grew up in this town. Everybody looks out for each other here,” said Lisa Kettyle, a founding member of the Big Bend Reproductive Coalition. Culbertson said the coalition has helped her plan her local protest events.

Natasha Acevedo, an outreach manager with Deeds Not Words, said Culbertson contacted the nonprofit last spring via Instagram. She shared her idea of a series of events around the state supporting reproductive freedom. The Roe v. Wade decision had “really made her feel heartbroken,” Acevedo said. Culbertson was one of the youngest activists they’d ever worked with, she’d reached out to them only about six weeks before the first event, and “she lived in a whole other country,” Acevedo said. But Culbertson “wanted some mentorship, and that’s what we do.” So the nonprofit agreed to help.

Deeds Not Words, which has been around about five years, has chapters on a handful of college campuses and is looking to add more. Acevedo said the group’s goal is to empower young people to deal with problems of gender inequality and to think about what a society built on equity would look like. “A lot of young people are very passionate about wanting things to change” but don’t know how to get started, Acevedo said. The nonprofit teaches them about building a community of like-minded people and starting with smaller concepts.

Acevedo helped Culbertson find the people she needed in each city, showed her how to create a pitch for her ideas, and met with her weekly to check on her progress. The 15-year-old was tenacious, passionate, and intelligent in how she dealt with people.

“She ended up having all the events she wanted,” Acevedo said, even though turnout was small for some. It shows that “no matter how young you are, you can make a difference.”

Culbertson said her aim is to “continue to grow awareness” about the repercussions of Texas’ severe abortion laws. A year after Roe v. Wade was overturned, she told the Big Bend Sentinel, “It’s still important to keep on marching … because this hasn’t gone away yet. And I’m not going to stop until it does go away.”

Texas needs an Observer! Become a member to get our magazine, six times per year!

#students#activism#roe v. wade#abortion rights#reproductive rights#reproductive health#marfa texas#marfa#paris texas#Texas#teenagers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

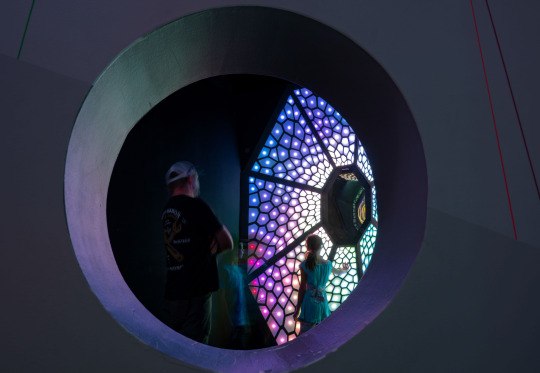

“Beyond the Refrigerator Door” by Kit O'Connell, from the November/December 2023 issue of Texas Observer magazine, with photography by Erika Nina Suárez:

Above: The Neon Kingdom stage at Meow Wolf Grapevine, which the artist collective plans to use for community events and local musicians.

One moment, I’m standing in a drab hallway in the Grapevine Mills shopping mall, listening to the sound of blankness. When I enter “The Real Unreal”—the fourth permanent installation from artist collective Meow Wolf, and the first in Texas—I hear a gentle, whooshing static. It’s a palate cleanser, like a drink of water before tasting something new. Then, I step through a heavy office door into another world.

I’m in a lush suburban backyard in Bolingbrook, Illinois. Crickets chirp, mingling with the sound of traffic, far enough away that it adds to the sense of coziness and peace. The air even smells like earth and tomato plants from the vegetable garden, lit by gentle fairy lights.

The Delany House is the entrance point into The Real Unreal and is the home to ficitional jazz musician Gordon Delany and his family set in Bolingbrook, Illinois.

Up ahead past the yard, purple light oozes from a two-story home’s circular dormer window. Below, the white streaks on the eggplants seem a little too drippy, the gourds a little too bulbous and tentacled. It only gets stranger when I step inside, where the walls bulge, the doors of the washer and dryer open into playground slides, and the fireplace and closet serve as portals to other dimensions—“Lightning Room,” a research base where scientists are trying to stop time, and a trippy neon forest replete with weird sculptures and fantastical creatures. The refrigerator door leads to “Brrrmuda,” a chilly hub where numerous pathways meet. Each of the hub spaces in the looping, maze-like exhibition leads to more rooms brimming with imaginative creations.

Opened in July in a former anchor store in this Texas-sized mall, the installation takes up over 24,000 square feet across two stories. “The Real Unreal” is the work of more than 150 artists—40 of them from Texas—that is both an avant-garde art gallery and an experiment in storytelling. When you attend a Meow Wolf exhibition, the goal is to make you feel like part of the art rather than a spectator. The result is a powerful experience that immerses visitors in uninhibited human creativity. Once you’re admitted, you can take as long as you want inside. Connor Gray, the PR manager, told me the average visit is about two hours, but some people stay all day.

“This used to be a Bed, Bath, & Beyond,” Gray told me. “Now, we’re just beyond.”

According to Kaitlyn Armendáriz, the impact manager for Meow Wolf Grapevine and an adjunct art history professor at Collin College, the installation shatters the illusion that contemporary artwork is stuffy, dull, or exclusionary.

“The thing that excited me most [about Meow Wolf] was this idea of the breakdown between the viewer and the art,” Armendáriz said. “I really like that it’s truly art for everybody, and art for all.”

Meow Wolf rewards the curious mind with layer after layer to be peeled back. You can interact with almost everything—touch, read, and press. This is art you can hear and smell, too. The space is densely packed, with many rooms brimming with sculptures and crafted delights. In others, a single, massive artwork stands alone in its own gallery.

Because visiting Meow Wolf can be disorienting, the creators went to some length to make it as accessible as possible. Though you can crawl, slide, or take the stairs between levels, elevators are available. A kit with earplugs and other tools, to help autistic visitors and those who need a bit less sensory input, is available free from the gift shop.

Opening a refrigerator door in the kitchen of The Delany House takes guests into a dome shaped, portal like space called the BRRRMUDA, with multiple refrigerator doors on all sides. Each door on the ground floor can be opened and all lead to a different location.

While the attraction is child friendly, in September the team launched Adultiverse, special 21-and-up nights with bands playing in a colorful onsite event space with a bar. Although tickets for grownups start at $35—climbing to $50 on weekends and other peak days—organizers have given away more than 5,000 free tickets since they opened, many to students at schools the government deems to be the most impoverished. According to Armendáriz, they also offer significant discounts to all schools and community groups, even frequently to groups that aren’t formal nonprofit organizations.

“All of our sites donate tickets because cost and transportation, regardless of where you’re at, are the two biggest barriers to getting people into the arts,” she said, “so if we can eliminate the barrier of cost we’ll do that.”

Armendáriz told me that traditional museums have historically excluded marginalized groups, though she acknowledged many of them are working to become more diverse.

“It takes decades and decades to undo decades and decades of harm,” she said.

The power of Meow Wolf is that it started fresh, without all the baggage of traditional art galleries.

“Meow Wolf [came] in as this disruptor … because it was new and it was created by enthusiastic and idealistic individuals and was started with this mission to do good and to make art accessible,” Armendáriz added.

Meow Wolf began in Santa Fe in 2008, founded by a group of independent artists looking for unconventional ways to showcase their creations. Much like the Grapevine location, the Santa Fe installation is built around a suburban home that leads to galleries representing other worlds. From there, they took their installations to more cities, creating a unique theme for each. At each location, Denver (a planet where four alternate dimensions meet), Las Vegas (a superstore called Omegamart), and now Grapevine, core members of the Meow Wolf team recruited local artists and talent, from guides and gift shop employees to sound and lighting designers.

Refractive glasses give travelers in The Real Unreal a new perspective on the Neon Kingdom.

From the start, the artists’ unique and captivating vision attracted backers like the Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin, who helped purchase their first location at a defunct bowling alley. Then, more than 800 people contributed to Meow Wolf’s Kickstarter campaign, which funded the alley’s conversion into an art space. Their popularity rapidly snowballed from there. For superfans of the Meow Wolf universe, “The Real Unreal” contains subtle references to previous installations, which encourages the community that’s grown around their art. Another location is slated to open next year in Houston.

“With Meow Wolf, it’s important that we take guests on that emotional journey,” Kelly Schwartz, the Grapevine general manager said.

If visitors aren’t immediately enraptured by the art, the mystery at the heart of “The Real Unreal” can hook them instead. Parts of the exhibition—like the home of the Delaneys and Fuquas—function both as installation art pieces and as a visual narrative told in letters, text messages, souvenirs, and scrapbooks.

In this home, a family of five has gathered to care for their ailing patriarch, the jazz musician Gordon Delaney. They include Gordon’s daughter Carmen, who just moved back in to help; Carmen’s childhood friend Laverne Fuqua; and Laverne’s two children, Jerrica and Jerid, who recently went missing.

A “missing” poster in the living room reads, “Jared, we are not mad. We just want you to come home.”

A small opening reveals a hidden section of neon lights and a brightly lit hallway.

Other travelers crawl in and out of the warped fireplace with impossibly curving brick edges and stumble, dazed, out of the closet, a faraway look in their eyes. But I’m drawn to the color printout on the table. Have I seen this boy?

According to his sketchbook, one day Jared fell asleep in the weird closet under the stairs. When he woke up, the glass of water next to him contained a strange sea creature. It looks a bit like an axolotl, but is a unique species. It chirps and warbles, doesn’t seem to eat much food, and—strangest of all—only Jared seems to be able to see him. However, grandfather Gordon, who has gone blind, can hear it and likes the music it makes.

Jared’s clearly a sweet kid with a big heart and a special interest in sea creatures. Stickers, drawings, and pictures of aquatic life cover the wall and canopy over his bed. He’s nerdy (or fixated) enough that when he discovers the creature, he gives it a Latin name—Hapulusgarrulus Lapnoaquaflo, from the words meaning “soft” “talkative or chattering,” “tufted or crested,” “water,” and “flowering.” But for short, he calls it Happy Garry.

Gordon’s cough is getting worse, leading to a short-term hospitalization. When the family comes home, there’s no sign of Jared, who has followed his new pet Garry back into “The Real Unreal.” And no one has seen him since. Though the visitor never directly meets any of them, the story of Jared’s disappearance into other dimensions, written by Wisconsin science fiction author LaShawn Wanak, is laced throughout the museum.

“I like having those sorts of peaks and valleys in an experience, and having intentional design in that way so you might be in a room that’s super stimulating, but then you transition into a room where you can sit and reflect on that,” Schwartz said.

When I take a moment to rest on the comfy benches inside Baba Yaga’s hut, somewhere past “Brrrmuda,” I see Happy Garry staring back at me, floating in a jar with air holes punched in the lid, nestled among other sculpted oddities in a small glass cabinet. Baba Yaga’s hut, as is traditional in Russian mythology, stands on two giant chicken legs. Its feet cling to a massive tree in the psychedelic forest. Glowing mushrooms dot the tree trunk, pulsing and chiming as you touch them. A smiling guide in full drag makeup urged visitors to interact with the makeshift instrument or sent them off in search of a hidden, animated image of a hamster in a wheel. The guides help people into and—if necessary, when you get lost or overwhelmed—out of the attraction.

Nearly all objects within Meow Wolf's The Real Unreal universe are intended to be interacted with. Here in The Forest a guest interacts with objects mimicking mushrooms growing on a tree trunk. When tapped, each mushroom plays a different musical note.

You can ask the guides for a “side quest” such as hunting “brain beans,” small doodles of plants hidden throughout the attraction. Each one contains a hashtag that you text to a phone number, also provided. In response, Dug, the head gardener sends a small cartoon image as a sort of trophy for finding the bean, with another optional activity: “To plant this bean, make a pair of binoculars w/ your hands and focus on 1 detail in the environment. Sow this image in your head garden.”

The exhibit is full of almost overstimulating highs, like the cracking electricity and flashing lights of the time scientists or the dance party you can start with a push of a button inside “Brrrmuda,” complete with a disco ball made from frozen food. One doorway in the fridge-dimension features cartoon paletas with wild faces made by local artist Carlos Donjuan. But there are also quieter moments that left me with a lingering, peaceful feeling.

One artwork that I returned to multiple times during my visit, was “Crystal Cloud Cave” by Lance McGoldrick. As quiet ambient music plays in a narrow room, one wall shows a constantly evolving, AI-generated sky, always unique, that slowly transitions from day to night, with sunsets and sunrises and, if you’re lucky, a glimpse of the aurora borealis. Along the opposite wall, reflective cubes, haphazardly stacked, mirror the skyscape—and the travelers passing through the corridor between—at unusual angles. I felt calm there in a way that’s hard to put into words. If there’d been a bed there, I’d have drifted off into inner space until closing time.

A traveler inside Meow Wolf Grapevine pauses on a balcony to look down at Lamp Shop Alley.

One of Dug’s clues sent me back to one of my favorite parts of the attraction, called “Lamp Shop Alley.” Like “Brrrmuda,” the Alley is one of the hub spaces that leads to other art. It looks like an alien marketplace full of strange offerings behind closed shop windows; glowing signs for other imaginary vendors written in unearthly languages cover the walls. There are toys too, like an ATM that challenges you to unlock its secret code. Through yet another doorway a deliciously seedy arcade full of custom cabinets that you can play. The whole vibe reminds me of all the “bizarre bazaars” found in fantasy and science fiction, strange shopping districts on faraway worlds. I imagine myself as a tourist stepping out of the “Hidden Capsule Motel” in search of breakfast on an early morning on some other planet. The air hums with the subtle sounds of a city waking up.

Scwartz said that the Alley is one of her favorite parts of “The Real Unreal.”

“I love the level of detail, not only in the art that you see with your eyes, but in what you hear in the soundscape,” she told me. “It’s just incredible … the way it echoes and bounces off the different walls, what the artists have been able to do.”