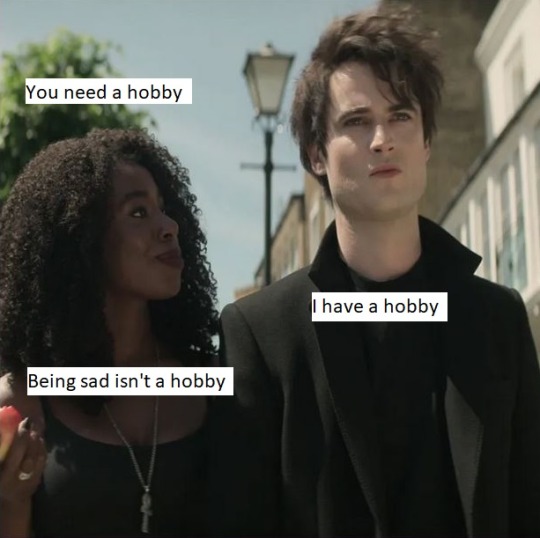

#who clearly stole his look off of 80's robert smith

Text

Everyone needs an older sibling to call them on their shit by lightly bullying them <3

#the sandman#dream of the endless#death of the endless#netflix the sandman#we all remember this meme right??#are we far enough into the tags that I can say#he needs a Hob-by?#I love this terrifyingly powerful god of dreams but also sad emo boy#who clearly stole his look off of 80's robert smith#dream of the endless the missing member of the cure#i made this#to my shame#meme of the endless

562 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was a Who's Who of the East Village scene—the legends of Post Pop Art gathered at the Pyramid Club in New York on September 4, 1986. Among the guests were Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, Marcus Leatherdale, Ann Magnuson, Karen Finley, John Sex, Wendy Wild, Steve Rubell, Andy Warhol and, of course, Madonna. They were gathered to celebrate and support one of their own, the artist, Martin Burgoyne.

Though a central figure in the scene that would become the hallmark of the era, and a contemporary of many of the leading names in art and music of his generation, Burgoyne is little known outside the Madonna fandom. Shortly after arriving in New York to attend the Pratt Institute, Burgoyne met Madonna and the two moved in together after Madonna was robbed by neighborhood kids who stole her music equipment and Burgoyne (who lived in an adjoining apartment) was robbed two days later. Burgoyne was instrumental in the early stages of Madonna's career: According to Edo Bertoglio, whose film, New York Beat, resurfaced years later as the indie hit Downtown81, starring Jean-Michal Basquiat and Debbie Harry, "Martin Burgoyne... always advised [Madonna] on where to go, how to dress, with whom to go out, what were the right places." Burgoyne did the art work for the cover of the single, "Burning Up," which later appeared on Madonna's first album. The first album was originally called, Lucky Star, and Burgoyne designed the original art work (it was abandoned in favor of the famous black and white photo that graced the cover). Later, Burgoyne designed album covers for DJ Jellybean Benitez, the Jamaica Girls and General Public. He worked as Madonna's road manager for a brief tour promoting her first singles and was a dancer for Madonna's first live performance of her single "Everybody," at Haoui Montaug's No Entiendes, a cabaret show Montaug hosted at Danceteria.

Like many artists who went on to become famous, Madonna and Burgoyne worked and played at Danceteria in the early 80's, where among the crowd of then-unknowns was another Who's Who of the era: Madonna worked the coat check, the Beastie Boys were waiters, Keith Haring painted Danceteria's interior and worked as a bus boy as did David Wojnarowicz; while LL Cool J and Debi Mazar worked the elevators and Sade tended bar. By that time, circa 1982, Danceteria eclipsed its predecessors as the hub of the art/club scene of the day, and Madonna and Burgoyne were regular fixtures. "They were like fraternal twins," wrote Jordan Levin in the Miami Herald "Cherubic urban imps with identical curly blond hair and precisely ragged, tight black clothing." Though Madonna's irrepressible energy and unrelenting ambition were off-putting to most, Burgoyne, by all accounts, was universally liked and admired. "He was... much beloved and lusted after," wrote Levin, "an incandescent boy even in the darkest after-hours club."

When Madonna was practicing her pirouettes at Martha Graham, modeling nude at the New School and playing at Max's Kansas City, CBGB's and dives in New Jersey—striking her best Pat Benatar pose while doing her Chrissie Hynde imitation—the punks and art students of the East Village were gathering at Club 57 and the Mudd Club. Sibling clubs with a fair amount of sibling rivalry, each was a Warholian mix of art, theatre, film and music. The clubs held the first showings by soon-to-be-renowned figures like Kenny Scharf (whose first show was at Club 57 in September '79), Keith Haring (his Erotic Art Show premiered in August 1980), and Jean-Michel Basquiat (whose No Wave band, Gray, played at the Mudd Club) amid live music by punk and New Wave bands, screenings of No Wave films by Amos Poe (among others) and a constant rotation of New Wave cabaret acts like John Sex (whose Acts of Live Art premiered in April 1980) Wendy Wild, Karen Finley and Ann Magnuson who was also the manager of Club 57.

Born of the vestiges of the punk scene at CBGB's, Mudd Club was the anti-Studio 54, albeit with its own door policy and just enough star power (Bowie, Warhol, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg frequented the club; Bowie filmed the video for his song "Fashion," there) to give it a celebrity sheen while maintaining its street cred. Mudd Club was the darker twin to the decadent free-for-all and campy shenanigans of Club 57, which, in addition to art and cabaret shows, hosted Ladies Mud Wrestling and a Monster Movie Night. Still, enough competition existed to inspire Steve Mass, owner of the Mudd Club, to lure Ann Magnuson to come to work for him in 1981 and where Magnuson went, others followed. Haring became curator of Mudd Club's fourth floor art gallery, though by that time (after the New York/New Wave show at PS 1 that year, often regarded as the Armory Show of the 80's) Basquiat, among others, was commanding thousands of dollars and selling to wealthy collectors despite considerable debate over whether the work was worthy or mere novelty. At the same time, the music in the clubs was also changing. Many of the East Village artists were graffiti artists themselves or were in with the graffiti artists like Fab Five Freddy and Futura 2000 who in turn were familiar with both the punk/New Wave bands of downtown and the rappers and break dancers of the emerging Hip Hop scene in the South Bronx. That the seemingly disparate groups—artists, musicians, rappers—of seemingly disparate styles would eventually converge was all but inevitable.

Anita Sarko began her stint as DJ at the Mudd Club shortly after arriving in New York in 1979, spinning an eclectic mix of oldies, rarities, punk and New Wave, playing anything that got people moving. Sarko eventually left Mudd Club for Danceteria in 1983 and there she co-hosted No Entiendes with Haoui Montaug, famed door man of Hurrah, the Mudd Club and Danceteria. Like Club 57 and the Mudd Club, Danceteria was a Factory-like mix of art, film and music and was also one of the first clubs to have a video lounge on its third floor, modeled after the video monitors that were installed at the Ritz (arguably the first club, in 1980, to have videos) and Hurrah, the club now credited as the birthplace of the video VJ. It is due in part to the performances that were filmed at the club and then played in Danceteria's video lounge (and earlier at Hurrah) that many of those early performances by Madonna, New Order and the Beastie Boys as well as Wojnarowicz's band, 3 Teens Kill 4, are available on YouTube and social media today, not to mention an installation at MOMA.

In videos and photos of Burgoyne and Madonna taken at the time the two are nearly identical due in no small part to Burgoyne's androgyny and gender-shifting fluidity. The two appear like an inversion of early photos of Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith: Both blond, seraphic and playful where Patti and Robert were shabby, dark and brooding; New Wave chic where Patti and Robert were gothic proto-punk. In one set of pictures Burgoyne and Madonna are dressed identically in ripped denim and white T's, arms covered in black rubber bracelets, a mop of gold hair spilling out of the caps they are both wearing. In another, they both don pink punk wigs (Madonna wore hers on an early appearance on British television). In another set—taken during the filming of Desperately Seeking Susan—Madonna sits on Burgoyne's lap, both dressed in identical jeans, leather boots and leather jackets. What is most striking in the photos, however, is Burgoyne's blatant femininity: Like Madonna, he dons armfuls of rubber bracelets, large hoop earrings and wears nail polish, black eyeliner and lip gloss, his lips pursed—like Madonna's—kissing at the camera. Though he was fond of the leather attire common to the clone and S & M scenes of the gay community at that time, he also cultivated an androgynous look more common among the British New Romantics (who in turn were inspired by the glam rockers of the previous decade), a gender-fluid look that even at the time set him apart from the other downtown denizens of New York’s Lower East Side of the early 80’s. Though certainly, even at that time, artists like Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, and Wojnarowicz and performance artists like Jobriath, Klaus Nomi and Stephen Varble incorporated homo-aesthetics in their work, for Burgoyne it was more than a performance or a pose or even mere fashion; it seems—even in the most casual or private of photos—to have been his way of being in the world. Madonna’s own homo-aesthetic—and her influence on the artists who subsequently followed her—owe a debt to Burgoyne’s early influence on the fledgling diva who, clearly—given the mirroring of Burgoyne evident in the photos—took much of her own homo-aesthetic directly from Burgoyne (among others). According to Christopher Ciccone, in his admittedly trashy biography of his famous sister, it was Burgoyne who introduced Madonna to the seedier side of gay life, an edgy underworld that would become a prominent feature of her later, post-Sean Penn work. “He openly [played] on the dark side and [liked] it,” wrote Ciccone. “Perhaps due to her friendship with Marty, S&M [became] one of the leitmotifs of Madonna’s career.” Further, observed Ciccone:

“Marty [introduced] Madonna to photographer Edo Bertoglio and his girlfriend, French jewelry designer Maripol, who designed those seminal colored rubber bracelets that everyone else in the Village is now wearing as well. However mainstream and oft-imitated her concepts would later become, Maripol’s influence on Madonna’s image can’t be understated, as she is responsible for creating her punk-plus-lace look.”

Neither, then, can Burgoyne’s influence be underestimated. However, like many anonymous gay men who dressed, shaped and helped form a Diva who would go on to, in Madonna’s own words, “rule the world,” Burgoyne has gone virtually unheard of and—like his own work—remained all but obscured.

There are photos of Burgoyne clubbing with Keith Haring and a later photo of Burgoyne riding in the limo with Warhol on the way to Madonna's wedding to Sean Penn (Warhol was Burgoyne's plus-one at the wedding according to Warhol's diary); in all the photos of Burgoyne from that time it is clear that these legends adored him; both Haring and Warhol wrote in their diaries of their devastation at Burgoyne’s death. However, Burgoyne remains elusive in most of the candid pictures taken at Danceteria or the Mudd Club or such celebrity gatherings; he is there but immersed in the crowd or just off to the side. In one photo, for example, Burgoyne peeks out from the edge of the picture, eyes locked with Madonna as she commands the center of a dancefloor. In the video of Madonna's performance at Live Aid, Burgoyne is there just off stage while Madonna sings a medley of her hits. Sean Penn and Keith Haring are just off stage to her left; Burgoyne is opposite, crouched on the floor nearby to Madonna's right, watching from the wings.

Like Warhol and the Warhol superstars, this generation of young artists, writers and performers coveted celebrity and were eager for the riches and success that were the zeitgeist of the greed-is-good 80's. After Basquiat's first showing at Nosei in '81, and Haring's first showing at Tony Shafrazi in '82, the art world took notice. The Whitney Biennial in '83 legitimized the East Village art scene and with legitimization came money and the beginnings of the gentrification that has left New York homogenized and unrecognizable; unlivable for anyone but the wealthy even to this day. When Haring was attacked at his '85 showing at Shafrazi by purist horrified by the gentrification in the Village brought on by the influx of money and notoriety, the East Village Eye declared that the scene was officially over before it started: "We, who were the first to take credit for the birth of East Village art," wrote Carlo McCormick, "now want to take credit for killing it." Then, in February 1987, Michael Musto of the Village Voice issued the final blow when he wrote about what he called, “The Death of Downtown,” following Warhol's passing. Martin Burgoyne died three months earlier of complications from AIDS surrounded by his parents and friends, including Haoui Montaug and Madonna, who held his hand while he died. In 2015, 2017, and again in 2018 to commemorate World AIDS Day, Madonna tweeted photos of herself and Burgoyne from the old days. "If we only knew then," she wrote "all the things that would happen."

According to Keith Haring's journal, he saw Burgoyne on the Fourth of July 1986 and Martin told him that he recently tested negative for the HIV virus. "But when I saw him," wrote Haring, "I saw death." Jordan Levin saw Burgoyne around that time outside the Pyramid Club, complaining of exhaustion and recurring bouts of the flu. “When I got sick," Burgoyne later told Michael Schnayerson from Vanity Fair, "they thought I had measles, so I stayed in for a month.” By August, according to Warhol in his diary, Burgoyne was sick and preparing to return to Florida where his parents lived: "[W]hat they thought was the measles wasn't," Warhol wrote, “And I said that the people we knew who had "it" had had the best care money can buy, and they were the first to go, so I didn't know what to say.”

By late August, when Warhol saw Burgoyne backstage after Madonna's play,Goose and TomTom, Burgoyne's face was covered with sores. He asked Warhol to draw a picture of him for a party to raise money for his medical costs to be held at the Pyramid Club in September. Warhol drew the picture and Keith Haring designed the invitations for the benefit, held on September fourth.

A feature about the party and the group of artists gathered there appeared in the New York Times. Hosted by Burgoyne's friends and caregivers Deb Parker and Jody Kurilla, guests and performers included Madonna, Haring, Warhol, John Sex and Wendy Wild, Haoui Montaug, and Walter Durcatz (DJ at Danceteria and the Pyramid Club who left Danceteria when someone fell down an elevator shaft). Marcus Leatherdale did a slide show. Karen Finley—the poet and performance artist who was later one of the notorious NEA Four—also performed. According to the New York Times, Burgoyne was told three weeks prior that he had ARC (AIDS related complex) and was too weak to dance, but joined in, "kissing and hugging his friends." ''We have all been friends for years and years," Haring told the New York Times, "since the days at Club 57.'' Six thousand dollars was raised that night to help pay Burgoyne's living expenses. Steve Rubell noted, "We know many AIDS patients who have been deserted, treated like lepers by their own families.'' AIDS had, by 1986, become an all-too-common occurrence for most in the once thriving East Village scene. Most at the party knew several friends who had already died. ''It's like a war is going on,'' said designer, Katy K. Reports leaked in The New York Post and the National Enquirer that Madonna's former roommate was dying of AIDS and that her support of her friend had caused strife in the notoriously volatile marriage of the Poison Penns. Sean Penn is often portrayed by Madonna's biographers as homophobic and paranoid about AIDS, but not so, according to Jordan Levin: "Martin was frantic," when the stories came out according to Levin, "[H]e'd been publicly branded a plague outcast who horrified his best friend's husband.” "`Sean isn't angry at me,'” Burgoyne assured Levin, “'I saw them last week and he hugged me. How can they do this?'" It was Sean Penn, in fact, according to Madonna biographer, J. Randy Taraborrelli, who traveled to Mexico at Madonna’s behest to obtained experimental drugs they hoped would prolong Burgoyne's life. By October, however, he was too sick with "cancer," Warhol wrote in his diary, to attend Kenny Scharf's Halloween party with Warhol. On November tenth, Madonna appeared in an auction at Barney's in which denim jackets designed by various artists and modeled by various celebrities were sold to raise money for St. Vincent's AIDS ward. The model, Iman, wore a jacket designed by Keith Haring; Madonna wore a jacket designed by Martin Burgoyne who was, himself, receiving treatment at St. Vincent’s. "I had a dream last night," Burgoyne told Vanity Fair two weeks before his death, "that I went to the art-supply store and there were so many things I wanted. But I couldn’t have any of them. All I want to do is work, work, work," he said, "And I can’t, can’t, can’t."Before 1980, there were fifteen AIDS-related deaths in NYC; by 1981 there were seventy-four AIDS related deaths when The New York Times reported on page twenty that year about a "rare cancer" afflicting gay men. In 1982, there were two hundred and seventy-six AIDS deaths and eight hundred and sixty-four AIDS deaths the following year. "Health Chief Calls AIDS Battle 'No. 1 Priority'," read a headline in the New York Times on May 24, 1983—the first time AIDS made the front page of the paper. By 1984 there were one thousand nine hundred and sixty AIDS deaths in New York City and by 1985 the number of deaths doubled. President Ronald Reagan, in a response to questions at the National Institute of Health that year, mentioned AIDS publicly for the first time, stating that he did not think children with AIDS should be allowed to attend school until it was certain the virus could not be passed by casual contact. He did not mention the epidemic publicly again until 1987. By 1986 there were six thousand four hundred and fifty-eight AIDS deaths in New York City alone. Martin Burgoyne died on November 30th, 1986. He was twenty-three years old.

#Martin Burgoyne#Madonna#Keith Haring#Marcus Leatherdale#New York#1980's#East Village#New Wave#No Wave

18 notes

·

View notes