#the groove had ceased to avail me

Text

Sorry it's been awhile since I effusively gushed over Jonathan Harker's emotional intelligence. Like really take a moment to think about this passage.

"I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself."

Now, it's a beautiful passage, but it's also the kind of thing people pay a therapist to tell them about themselves. The fact that Jonathan simply understands himself and his own emotions and furthermore is able to express himself so clearly to a stranger... Like that is a skill. Not everyone is capable of that.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself." - Jonathan Harker

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself.”

Dracula by Bram Stoker

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

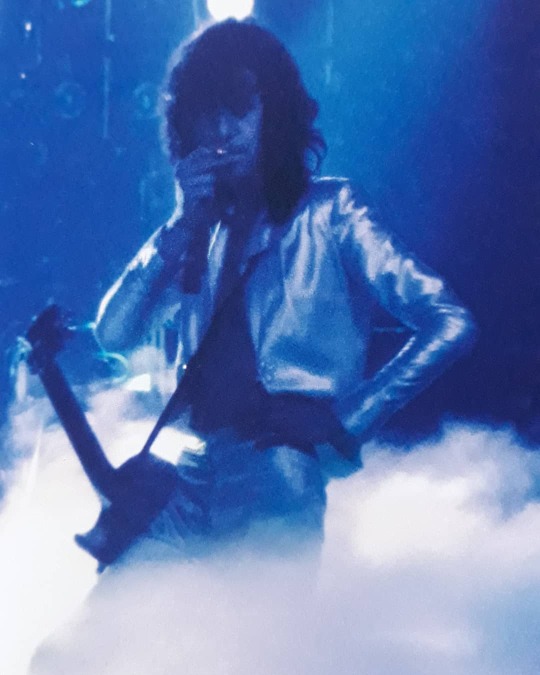

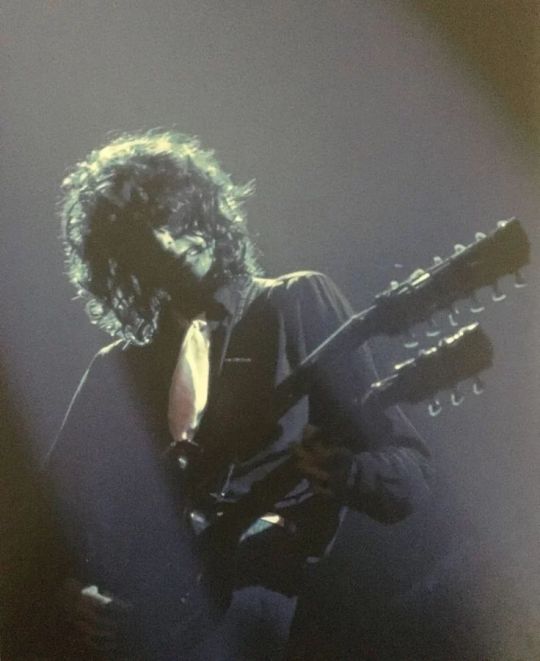

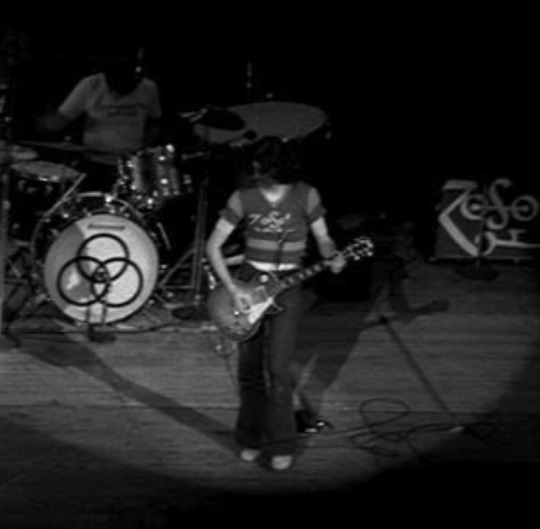

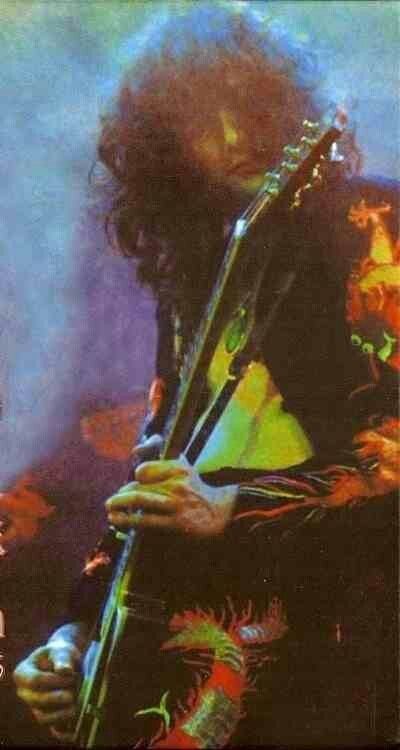

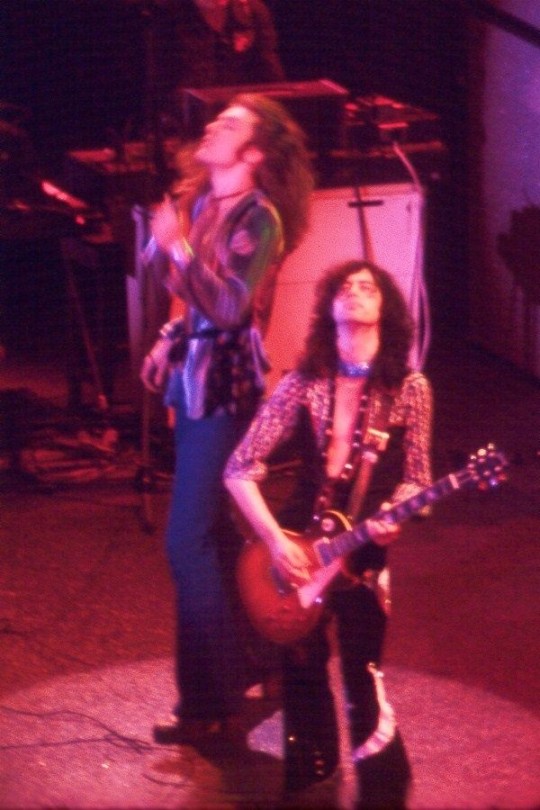

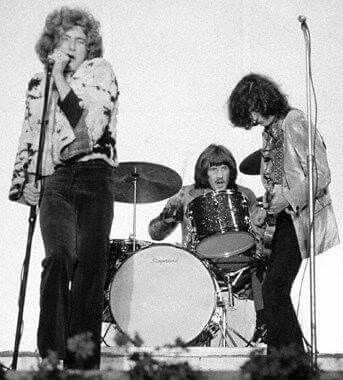

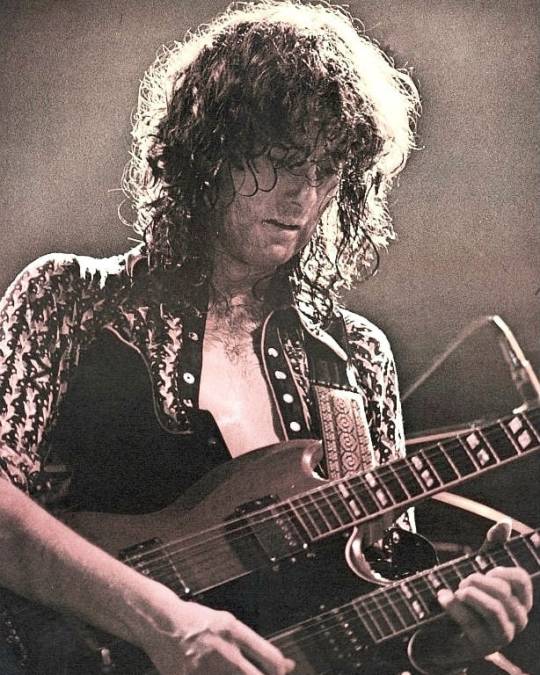

Discover Jimmy Page pt. 3

The Mighty Zeppelin

from pageysartgallery

How to start writing about something that was bigger than anyone involved, even bigger than its own creator?

In the Zeppelin realm, myth and real happenings merge together to form a bittersweet reality, that first made its leader a man of godlike status and then slowly killed its own divinity.

From its creation to the very end, Led Zeppelin has been a colossal, thunderous force that changed the world of rock and roll forever, architect of a sound considered underground at first, that proceeded to take over the world with its infectious groove.

All thanks to the ambitious mind of one gifted 24 year old.

After plans of an alleged band featuring himself, his longtime friend Jeff Beck, Keith Moon and John Entwistle got cancelled, Jimmy Page, then 22, decided to continue the path he was on with his current band, the Yardbirds, which quickly enriched him with brand new experiences around the world, for the first time as a member of a well-known rock and roll band.

He started being praised for his unique playing style, as well as the countless revolutionary ideas he was applying to live performances and slowly collecting for an upcoming album.

While in Los Angeles with the Yardbirds in May 1968, Jimmy visited a palm-reader and brought tour manager Richard Cole along with him.

“It was on Sunset Boulevard, not far from the hotel. Richard was with me so I’ve got a witness. The key phrase was, ‘You're going to make a decision in a very short period of time that's going to change your life.’ Within 48 hours the other Yardbirds said they didn't want to continue. I was disappointed – what we had going I was willing to do with them, whatever it was. I can understand how disillusioned they were, but I could see the trajectory. FM radio was happening. I knew what that meant to underground bands. I wanted an underground band, but one that would come through and make a difference.”

— Jimmy Page, Rolling Stone

What would follow is a long, almost obsessive search for musicians available around his area, but after two weeks nothing had changed yet. Page then reached out to Terry Reid, a vocalist and guitarist whose work he had become interested in. Reid turned down the offer, explaining that he had already committed to go on the road for two tours with the Rolling Stones and another with Cream. He suggested to Page that if he were compensated for the gig fees he would lose and if Page would call Keith Richards to explain why Reid had to pull out of the US tours, Reid would try some things out with Page. It never happened and Reid told Page to consider a young Birmingham-based singer, Robert Plant, instead, having previously seen Plant's Band of Joy as a support act at one of his concerts. Reid also suggested Page check out their drummer John Bonham.

The New Yardbirds - soon to be Led Zeppelin* following a cease and desist letter issued by Chris Dreja - became one of the best-selling acts of all time, with strong musical morals and an eagerness to expand and explore their individual and collective abilities as much as they could.

*Why the name Led Zeppelin? Because it brought “the perfect combination of heavy and light, combustibility and grace” to Page's mind.

They broke records and earned a reputation for excess, but most importantly, they gained a steady place in the hearts of countless musicians and/or fans, a place that would endure the passage of time and still be here, today, after more than half a century.

What's curious about this 12 year period is that Jimmy continued his career as a session musician, too. Collaborators around this time include Joe Cocker, Chris Farlowe, P.J. Proby, Screaming Lord Sutch and Roy Harper.

My favourite tracks from this time period are the ones he recorded with Maggie Bell! She has a voice easily comparable to Janis Joplin's, and Jimmy's solos on these two songs are absolutely flawless and full of page-isms:

(Released March 31, 1975)

Another song I'm fond of is "Male Chauvinist Pig Blues", where Jimmy's electric guitar can be heard throughout the entire track:

(Released February 14, 1974)

And of course the live version of the song (part of Roy's Flashes from the Archives of Oblivion live album), in which a stunning slide guitar performance is delivered by Page:

youtube

(Released 1974)

As for Led Zeppelin, a remarkable piece of their early history is the first studio track all four members ever recorded together on August 25, 1968. Part of the P.J. Proby album Three Week Hero, the name of the track is "Jim's Blues" (featuring Robert Plant on harmonica):

youtube

Also worthy of notice is the first Zeppelin bootleg ever recorded, from their December 30, 1968 show in Spokane, Washington.

youtube

I really recommend checking out the bootlegs because a big part of what separated Led Zeppelin from other bands were their outstanding live performances and on-stage improvisations! If you may need a guide to the best bootlegs in order to get started, here's a really helpful one.

One song from the earlier years that was to be recorded as part of their first album - but probably got discarded to make place for other tracks - is my beloved As Long As I Have You:

(This version was performed at the Fillmore West on April 27, 1969)

Personally I will never forgive them for not including it as it's one of my favourite Zep songs ever.

As we all know, after many years and quotes of Robert Plant swearing that the band may as well “go on forever”, the tragic death of John Bonham on September 25, 1980 at Jimmy Page's then recently acquired Old Mill House, after a long day of alcohol binges, is what finally put an end to the giant that was, and forever will be, Led Zeppelin.

“Led Zeppelin wasn't a corporate entity. Led Zeppelin was an affair of the heart. Each of the members was important to the sum total of what we were. I like to think that if it had been me that wasn't there, the others would have made the same decision. What were we going to do? Create a role for somebody? Say, ‘You have to do this, this way?’ That wouldn't be honest.”

— Jimmy Page, 2014

Live performance:

There are quite a few professionally filmed concerts included as part of the 2003 Led Zeppelin DVD that you can watch on YouTube:

1970.01.09 London, Royal Albert Hall

1973.07.27, 28, 29, New York City, Madison Square Garden

1975.05.24 London, Earl's Court

1975.05.25 London, Earl's Court Arena

1979.08.04 Stevenage, Knebworth Festival

1979.08.11 Stevenage, Knebworth Festival

However, there is one more fully filmed concert that was not included in the DVD. It's the July 17, 1977 concert in Seattle:

youtube

Interview:

There is only one available filmed Jimmy interview on YouTube from the Zeppelin years that everyone and their mum has seen lol (the Sept. 18th 1970 one), so instead I want to include this other one, only recorded - not filmed, but a very precious piece of musical history nonetheless:

youtube

He addresses many topics and is quite talkative for 1977, a time when he would just stand up from his chair and say “I'm really not sorry to say the interview has ended” when the interviewer seemed to get on his nerves.

Gallery:

#discover jp#pageysartgallery#jimmy page#led zeppelin#robert plant#john bonham#john paul jones#classic rock#classic rock fandom#rock and roll#hard rock#blues rock#60s#70s#by dee dee 🌺🕯️#my writing#SoundCloud

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

(very vague minor spoiler for September 26th Dracula ahead)

"I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don't know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself. No, you don't; you couldn't with eyebrows like yours."

i understand why Stoker thought this made sense at the time, but the eyebrows line just cracked me up today. that whole paragraph of heartfelt and determined courage and then that

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jonathan Harker running into Dracula in England.

“Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself.” - Dracula Daily, September 26

#dracula daily#you threw off my groove#september 26#I know a lot of stuff happened in todays email#but this is all that was going through my head

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dracula: September 26 - Jonathan and Mina have a nice quiet dinner, while the boys go sneaking into cemeteries

Jonathan Harker's Journal.

26 September.—I thought never to write in this diary again, but the time has come. When I got home last night Mina had supper ready, and when we had supped she told me of Van Helsing's visit, and of her having given him the two diaries copied out, and of how anxious she has been about me. She showed me in the doctor's letter that all I wrote down was true. It seems to have made a new man of me. It was the doubt as to the reality of the whole thing that knocked me over. I felt impotent, and in the dark, and distrustful. But, now that I know, I am not afraid, even of the Count. He has succeeded after all, then, in his design in getting to London, and it was he I saw. He has got younger, and how? Van Helsing is the man to unmask him and hunt him out, if he is anything like what Mina says. We sat late, and talked it all over. Mina is dressing, and I shall call at the hotel in a few minutes and bring him over....

He was, I think, surprised to see me. When I came into the room where he was, and introduced myself, he took me by the shoulder, and turned my face round to the light, and said, after a sharp scrutiny:—

"But Madam Mina told me you were ill, that you had had a shock." It was so funny to hear my wife called "Madam Mina" by this kindly, strong-faced old man. I smiled, and said:—

"I was ill, I have had a shock; but you have cured me already."

"And how?"

"By your letter to Mina last night. I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don't know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself. No, you don't; you couldn't with eyebrows like yours." He seemed pleased, and laughed as he said:—

"So! You are physiognomist. I learn more here with each hour. I am with so much pleasure coming to you to breakfast; and, oh, sir, you will pardon praise from an old man, but you are blessed in your wife." I would listen to him go on praising Mina for a day, so I simply nodded and stood silent.

"She is one of God's women, fashioned by His own hand to show us men and other women that there is a heaven where we can enter, and that its light can be here on earth. So true, so sweet, so noble, so little an egoist—and that, let me tell you, is much in this age, so sceptical and selfish. And you, sir—I have read all the letters to poor Miss Lucy, and some of them speak of you, so I know you since some days from the knowing of others; but I have seen your true self since last night. You will give me your hand, will you not? And let us be friends for all our lives."

We shook hands, and he was so earnest and so kind that it made me quite choky.

"And now," he said, "may I ask you for some more help? I have a great task to do, and at the beginning it is to know. You can help me here. Can you tell me what went before your going to Transylvania? Later on I may ask more help, and of a different kind; but at first this will do."

"Look here, sir," I said, "does what you have to do concern the Count?"

"It does," he said solemnly.

"Then I am with you heart and soul. As you go by the 10:30 train, you will not have time to read them; but I shall get the bundle of papers. You can take them with you and read them in the train."

After breakfast I saw him to the station. When we were parting he said:—

"Perhaps you will come to town if I send to you, and take Madam Mina too."

"We shall both come when you will," I said.

I had got him the morning papers and the London papers of the previous night, and while we were talking at the carriage window, waiting for the train to start, he was turning them over. His eyes suddenly seemed to catch something in one of them, "The Westminster Gazette"—I knew it by the colour—and he grew quite white. He read something intently, groaning to himself: "Mein Gott! Mein Gott! So soon! so soon!" I do not think he remembered me at the moment. Just then the whistle blew, and the train moved off. This recalled him to himself, and he leaned out of the window and waved his hand, calling out: "Love to Madam Mina; I shall write so soon as ever I can."

Dr. Seward's Diary.

26 September.—Truly there is no such thing as finality. Not a week since I said "Finis," and yet here I am starting fresh again, or rather going on with the same record. Until this afternoon I had no cause to think of what is done. Renfield had become, to all intents, as sane as he ever was. He was already well ahead with his fly business; and he had just started in the spider line also; so he had not been of any trouble to me. I had a letter from Arthur, written on Sunday, and from it I gather that he is bearing up wonderfully well. Quincey Morris is with him, and that is much of a help, for he himself is a bubbling well of good spirits. Quincey wrote me a line too, and from him I hear that Arthur is beginning to recover something of his old buoyancy; so as to them all my mind is at rest. As for myself, I was settling down to my work with the enthusiasm which I used to have for it, so that I might fairly have said that the wound which poor Lucy left on me was becoming cicatrised. Everything is, however, now reopened; and what is to be the end God only knows. I have an idea that Van Helsing thinks he knows, too, but he will only let out enough at a time to whet curiosity. He went to Exeter yesterday, and stayed there all night. To-day he came back, and almost bounded into the room at about half-past five o'clock, and thrust last night's "Westminster Gazette" into my hand.

"What do you think of that?" he asked as he stood back and folded his arms.

I looked over the paper, for I really did not know what he meant; but he took it from me and pointed out a paragraph about children being decoyed away at Hampstead. It did not convey much to me, until I reached a passage where it described small punctured wounds on their throats. An idea struck me, and I looked up. "Well?" he said.

"It is like poor Lucy's."

"And what do you make of it?"

"Simply that there is some cause in common. Whatever it was that injured her has injured them." I did not quite understand his answer:—

"That is true indirectly, but not directly."

"How do you mean, Professor?" I asked. I was a little inclined to take his seriousness lightly—for, after all, four days of rest and freedom from burning, harrowing anxiety does help to restore one's spirits—but when I saw his face, it sobered me. Never, even in the midst of our despair about poor Lucy, had he looked more stern.

"Tell me!" I said. "I can hazard no opinion. I do not know what to think, and I have no data on which to found a conjecture."

"Do you mean to tell me, friend John, that you have no suspicion as to what poor Lucy died of; not after all the hints given, not only by events, but by me?"

"Of nervous prostration following on great loss or waste of blood."

"And how the blood lost or waste?" I shook my head. He stepped over and sat down beside me, and went on:—

"You are clever man, friend John; you reason well, and your wit is bold; but you are too prejudiced. You do not let your eyes see nor your ears hear, and that which is outside your daily life is not of account to you. Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot? But there are things old and new which must not be contemplate by men's eyes, because they know—or think they know—some things which other men have told them. Ah, it is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain. But yet we see around us every day the growth of new beliefs, which think themselves new; and which are yet but the old, which pretend to be young—like the fine ladies at the opera. I suppose now you do not believe in corporeal transference. No? Nor in materialisation. No? Nor in astral bodies. No? Nor in the reading of thought. No? Nor in hypnotism——"

"Yes," I said. "Charcot has proved that pretty well." He smiled as he went on: "Then you are satisfied as to it. Yes? And of course then you understand how it act, and can follow the mind of the great Charcot—alas that he is no more!—into the very soul of the patient that he influence. No? Then, friend John, am I to take it that you simply accept fact, and are satisfied to let from premise to conclusion be a blank? No? Then tell me—for I am student of the brain—how you accept the hypnotism and reject the thought reading. Let me tell you, my friend, that there are things done to-day in electrical science which would have been deemed unholy by the very men who discovered electricity—who would themselves not so long before have been burned as wizards. There are always mysteries in life. Why was it that Methuselah lived nine hundred years, and 'Old Parr' one hundred and sixty-nine, and yet that poor Lucy, with four men's blood in her poor veins, could not live even one day? For, had she live one more day, we could have save her. Do you know all the mystery of life and death? Do you know the altogether of comparative anatomy and can say wherefore the qualities of brutes are in some men, and not in others? Can you tell me why, when other spiders die small and soon, that one great spider lived for centuries in the tower of the old Spanish church and grew and grew, till, on descending, he could drink the oil of all the church lamps? Can you tell me why in the Pampas, ay and elsewhere, there are bats that come at night and open the veins of cattle and horses and suck dry their veins; how in some islands of the Western seas there are bats which hang on the trees all day, and those who have seen describe as like giant nuts or pods, and that when the sailors sleep on the deck, because that it is hot, flit down on them, and then—and then in the morning are found dead men, white as even Miss Lucy was?"

"Good God, Professor!" I said, starting up. "Do you mean to tell me that Lucy was bitten by such a bat; and that such a thing is here in London in the nineteenth century?" He waved his hand for silence, and went on:—

"Can you tell me why the tortoise lives more long than generations of men; why the elephant goes on and on till he have seen dynasties; and why the parrot never die only of bite of cat or dog or other complaint? Can you tell me why men believe in all ages and places that there are some few who live on always if they be permit; that there are men and women who cannot die? We all know—because science has vouched for the fact—that there have been toads shut up in rocks for thousands of years, shut in one so small hole that only hold him since the youth of the world. Can you tell me how the Indian fakir can make himself to die and have been buried, and his grave sealed and corn sowed on it, and the corn reaped and be cut and sown and reaped and cut again, and then men come and take away the unbroken seal and that there lie the Indian fakir, not dead, but that rise up and walk amongst them as before?" Here I interrupted him. I was getting bewildered; he so crowded on my mind his list of nature's eccentricities and possible impossibilities that my imagination was getting fired. I had a dim idea that he was teaching me some lesson, as long ago he used to do in his study at Amsterdam; but he used then to tell me the thing, so that I could have the object of thought in mind all the time. But now I was without this help, yet I wanted to follow him, so I said:—

"Professor, let me be your pet student again. Tell me the thesis, so that I may apply your knowledge as you go on. At present I am going in my mind from point to point as a mad man, and not a sane one, follows an idea. I feel like a novice lumbering through a bog in a mist, jumping from one tussock to another in the mere blind effort to move on without knowing where I am going."

"That is good image," he said. "Well, I shall tell you. My thesis is this: I want you to believe."

"To believe what?"

"To believe in things that you cannot. Let me illustrate. I heard once of an American who so defined faith: 'that faculty which enables us to believe things which we know to be untrue.' For one, I follow that man. He meant that we shall have an open mind, and not let a little bit of truth check the rush of a big truth, like a small rock does a railway truck. We get the small truth first. Good! We keep him, and we value him; but all the same we must not let him think himself all the truth in the universe."

"Then you want me not to let some previous conviction injure the receptivity of my mind with regard to some strange matter. Do I read your lesson aright?"

"Ah, you are my favourite pupil still. It is worth to teach you. Now that you are willing to understand, you have taken the first step to understand. You think then that those so small holes in the children's throats were made by the same that made the hole in Miss Lucy?"

"I suppose so." He stood up and said solemnly:—

"Then you are wrong. Oh, would it were so! but alas! no. It is worse, far, far worse."

"In God's name, Professor Van Helsing, what do you mean?" I cried.

He threw himself with a despairing gesture into a chair, and placed his elbows on the table, covering his face with his hands as he spoke:—

"They were made by Miss Lucy!"

DR. SEWARD'S DIARY—continued.

For a while sheer anger mastered me; it was as if he had during her life struck Lucy on the face. I smote the table hard and rose up as I said to him:—

"Dr. Van Helsing, are you mad?" He raised his head and looked at me, and somehow the tenderness of his face calmed me at once. "Would I were!" he said. "Madness were easy to bear compared with truth like this. Oh, my friend, why, think you, did I go so far round, why take so long to tell you so simple a thing? Was it because I hate you and have hated you all my life? Was it because I wished to give you pain? Was it that I wanted, now so late, revenge for that time when you saved my life, and from a fearful death? Ah no!"

"Forgive me," said I. He went on:—

"My friend, it was because I wished to be gentle in the breaking to you, for I know you have loved that so sweet lady. But even yet I do not expect you to believe. It is so hard to accept at once any abstract truth, that we may doubt such to be possible when we have always believed the 'no' of it; it is more hard still to accept so sad a concrete truth, and of such a one as Miss Lucy. To-night I go to prove it. Dare you come with me?"

This staggered me. A man does not like to prove such a truth; Byron excepted from the category, jealousy.

"And prove the very truth he most abhorred."

He saw my hesitation, and spoke:—

"The logic is simple, no madman's logic this time, jumping from tussock to tussock in a misty bog. If it be not true, then proof will be relief; at worst it will not harm. If it be true! Ah, there is the dread; yet very dread should help my cause, for in it is some need of belief. Come, I tell you what I propose: first, that we go off now and see that child in the hospital. Dr. Vincent, of the North Hospital, where the papers say the child is, is friend of mine, and I think of yours since you were in class at Amsterdam. He will let two scientists see his case, if he will not let two friends. We shall tell him nothing, but only that we wish to learn. And then——"

"And then?" He took a key from his pocket and held it up. "And then we spend the night, you and I, in the churchyard where Lucy lies. This is the key that lock the tomb. I had it from the coffin-man to give to Arthur." My heart sank within me, for I felt that there was some fearful ordeal before us. I could do nothing, however, so I plucked up what heart I could and said that we had better hasten, as the afternoon was passing....

We found the child awake. It had had a sleep and taken some food, and altogether was going on well. Dr. Vincent took the bandage from its throat, and showed us the punctures. There was no mistaking the similarity to those which had been on Lucy's throat. They were smaller, and the edges looked fresher; that was all. We asked Vincent to what he attributed them, and he replied that it must have been a bite of some animal, perhaps a rat; but, for his own part, he was inclined to think that it was one of the bats which are so numerous on the northern heights of London. "Out of so many harmless ones," he said, "there may be some wild specimen from the South of a more malignant species. Some sailor may have brought one home, and it managed to escape; or even from the Zoölogical Gardens a young one may have got loose, or one be bred there from a vampire. These things do occur, you know. Only ten days ago a wolf got out, and was, I believe, traced up in this direction. For a week after, the children were playing nothing but Red Riding Hood on the Heath and in every alley in the place until this 'bloofer lady' scare came along, since when it has been quite a gala-time with them. Even this poor little mite, when he woke up to-day, asked the nurse if he might go away. When she asked him why he wanted to go, he said he wanted to play with the 'bloofer lady.'"

"I hope," said Van Helsing, "that when you are sending the child home you will caution its parents to keep strict watch over it. These fancies to stray are most dangerous; and if the child were to remain out another night, it would probably be fatal. But in any case I suppose you will not let it away for some days?"

"Certainly not, not for a week at least; longer if the wound is not healed."

Our visit to the hospital took more time than we had reckoned on, and the sun had dipped before we came out. When Van Helsing saw how dark it was, he said:—

"There is no hurry. It is more late than I thought. Come, let us seek somewhere that we may eat, and then we shall go on our way."

We dined at "Jack Straw's Castle" along with a little crowd of bicyclists and others who were genially noisy. About ten o'clock we started from the inn. It was then very dark, and the scattered lamps made the darkness greater when we were once outside their individual radius. The Professor had evidently noted the road we were to go, for he went on unhesitatingly; but, as for me, I was in quite a mixup as to locality. As we went further, we met fewer and fewer people, till at last we were somewhat surprised when we met even the patrol of horse police going their usual suburban round. At last we reached the wall of the churchyard, which we climbed over. With some little difficulty—for it was very dark, and the whole place seemed so strange to us—we found the Westenra tomb. The Professor took the key, opened the creaky door, and standing back, politely, but quite unconsciously, motioned me to precede him. There was a delicious irony in the offer, in the courtliness of giving preference on such a ghastly occasion. My companion followed me quickly, and cautiously drew the door to, after carefully ascertaining that the lock was a falling, and not a spring, one. In the latter case we should have been in a bad plight. Then he fumbled in his bag, and taking out a matchbox and a piece of candle, proceeded to make a light. The tomb in the day-time, and when wreathed with fresh flowers, had looked grim and gruesome enough; but now, some days afterwards, when the flowers hung lank and dead, their whites turning to rust and their greens to browns; when the spider and the beetle had resumed their accustomed dominance; when time-discoloured stone, and dust-encrusted mortar, and rusty, dank iron, and tarnished brass, and clouded silver-plating gave back the feeble glimmer of a candle, the effect was more miserable and sordid than could have been imagined. It conveyed irresistibly the idea that life—animal life—was not the only thing which could pass away.

Van Helsing went about his work systematically. Holding his candle so that he could read the coffin plates, and so holding it that the sperm dropped in white patches which congealed as they touched the metal, he made assurance of Lucy's coffin. Another search in his bag, and he took out a turnscrew.

"What are you going to do?" I asked.

"To open the coffin. You shall yet be convinced." Straightway he began taking out the screws, and finally lifted off the lid, showing the casing of lead beneath. The sight was almost too much for me. It seemed to be as much an affront to the dead as it would have been to have stripped off her clothing in her sleep whilst living; I actually took hold of his hand to stop him. He only said: "You shall see," and again fumbling in his bag, took out a tiny fret-saw. Striking the turnscrew through the lead with a swift downward stab, which made me wince, he made a small hole, which was, however, big enough to admit the point of the saw. I had expected a rush of gas from the week-old corpse. We doctors, who have had to study our dangers, have to become accustomed to such things, and I drew back towards the door. But the Professor never stopped for a moment; he sawed down a couple of feet along one side of the lead coffin, and then across, and down the other side. Taking the edge of the loose flange, he bent it back towards the foot of the coffin, and holding up the candle into the aperture, motioned to me to look.

I drew near and looked. The coffin was empty.

It was certainly a surprise to me, and gave me a considerable shock, but Van Helsing was unmoved. He was now more sure than ever of his ground, and so emboldened to proceed in his task. "Are you satisfied now, friend John?" he asked.

I felt all the dogged argumentativeness of my nature awake within me as I answered him:—

"I am satisfied that Lucy's body is not in that coffin; but that only proves one thing."

"And what is that, friend John?"

"That it is not there."

"That is good logic," he said, "so far as it goes. But how do you—how can you—account for it not being there?"

"Perhaps a body-snatcher," I suggested. "Some of the undertaker's people may have stolen it." I felt that I was speaking folly, and yet it was the only real cause which I could suggest. The Professor sighed. "Ah well!" he said, "we must have more proof. Come with me."

He put on the coffin-lid again, gathered up all his things and placed them in the bag, blew out the light, and placed the candle also in the bag. We opened the door, and went out. Behind us he closed the door and locked it. He handed me the key, saying: "Will you keep it? You had better be assured." I laughed—it was not a very cheerful laugh, I am bound to say—as I motioned him to keep it. "A key is nothing," I said; "there may be duplicates; and anyhow it is not difficult to pick a lock of that kind." He said nothing, but put the key in his pocket. Then he told me to watch at one side of the churchyard whilst he would watch at the other. I took up my place behind a yew-tree, and I saw his dark figure move until the intervening headstones and trees hid it from my sight.

It was a lonely vigil. Just after I had taken my place I heard a distant clock strike twelve, and in time came one and two. I was chilled and unnerved, and angry with the Professor for taking me on such an errand and with myself for coming. I was too cold and too sleepy to be keenly observant, and not sleepy enough to betray my trust so altogether I had a dreary, miserable time.

Suddenly, as I turned round, I thought I saw something like a white streak, moving between two dark yew-trees at the side of the churchyard farthest from the tomb; at the same time a dark mass moved from the Professor's side of the ground, and hurriedly went towards it. Then I too moved; but I had to go round headstones and railed-off tombs, and I stumbled over graves. The sky was overcast, and somewhere far off an early cock crew. A little way off, beyond a line of scattered juniper-trees, which marked the pathway to the church, a white, dim figure flitted in the direction of the tomb. The tomb itself was hidden by trees, and I could not see where the figure disappeared. I heard the rustle of actual movement where I had first seen the white figure, and coming over, found the Professor holding in his arms a tiny child. When he saw me he held it out to me, and said:—

"Are you satisfied now?"

"No," I said, in a way that I felt was aggressive.

"Do you not see the child?"

"Yes, it is a child, but who brought it here? And is it wounded?" I asked.

"We shall see," said the Professor, and with one impulse we took our way out of the churchyard, he carrying the sleeping child.

When we had got some little distance away, we went into a clump of trees, and struck a match, and looked at the child's throat. It was without a scratch or scar of any kind.

"Was I right?" I asked triumphantly.

"We were just in time," said the Professor thankfully.

We had now to decide what we were to do with the child, and so consulted about it. If we were to take it to a police-station we should have to give some account of our movements during the night; at least, we should have had to make some statement as to how we had come to find the child. So finally we decided that we would take it to the Heath, and when we heard a policeman coming, would leave it where he could not fail to find it; we would then seek our way home as quickly as we could. All fell out well. At the edge of Hampstead Heath we heard a policeman's heavy tramp, and laying the child on the pathway, we waited and watched until he saw it as he flashed his lantern to and fro. We heard his exclamation of astonishment, and then we went away silently. By good chance we got a cab near the "Spaniards," and drove to town.

I cannot sleep, so I make this entry. But I must try to get a few hours' sleep, as Van Helsing is to call for me at noon. He insists that I shall go with him on another expedition.

----

Original Substack Post

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“By your letter to Mina last night. I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don’t know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself. No, you don’t; you couldn’t with eyebrows like yours.”

This quote is like…the perfect summation of everything I love and hate about Dracula. It’s a bunch of lines of this beautiful prose showing Stoker’s real understanding of his character’s psychology and trauma in a way that modern writers often have trouble with…and then it’s juxtaposed with absolutely BATSHIT* pseudoscience (and, since this is physiognomy** very racist pseudoscience at that!)

*by modern standards at least; I’m aware it was considered science at the time

**and because of who Stoker was as a person racist even for his time

#Dracula#Dracula daily#my good friend#Jonathan Harker#quotes#d rambles#Stoker contained multitudes#Unfortunately a lot of those multitudes were occupied and/or overshadowed by Being Extremely Racist#(And sexist ableist etc etc) (two etc necessary because BOY DID HE HAVE A LOT OF BIGOTRY)#Makes it hard to talk about it with people#“This book is really amazing in parts but he DOES use a lot of racial slurs” “and a mentally ill guy gets repeatedly put in a straitjacket”#“And everyone constantly talks about how different men and women are—”#“Hey come back I’m not done with my pitch yet”#“I promise it’s good”

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh no it is a chapter reference since he has. lost the groove now. he had said something similar in the book but I cannot remember how. the groove had forsaken me? ignore me.

Oh, okay, see, I didn't understand because you said it to me as if I were Jonathan.

Indeed, in his first conversation with Van Helsing, he does say that the groove ceased to avail him.

The groove certainly has fucked off once again. He is so so tired.

#update#people ask me things#orice#jonathan harker#as far as I know this isn't an rp blog no matter how much I stan these characters

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don’t know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself."

- Jonathan (Dracula, BS)

0 notes

Text

Sorry, sorry but, Jonathan this is so eloquent like

"I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don't know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself."

I have never experienced trauma or dealt with PTSD, vampire related or otherwise, but the way he puts it down here is so simple and easy to understand

86 notes

·

View notes

Quote

‘… I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don’t know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself. …'

Bram Stoker, Dracula

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

God’s Judgement

Important if you’re going to read this story! Any text with a ⛧ right next to it has a clickable link for translation! There is German text in this story. Please keep this in mind while reading.

Warnings for: Gore, Violence, Death, Religious Themes (Catholicism)

If you are a native German speaker and wish to help me with corrections, please do not be shy to approach me! I will highly appreciate it!

"Bewegung! Geh weiter!" ⛧

Angela cries as she’s kicked forward by guards. Her wrists burned from the rope that bound her arms behind her back. She had finally been captured by these men who have been tracking her down for months, and now she was their prisoner. Being treated like a dog as she trudged her way down the muddy path. "Bitte..." ⛧

"Halt die Klappe, Göre! Du bekommst endlich, was du verdienst. Gott wird derjenige sein, der dich richtet!" ⛧ The same guard kicks her again and she falls forward, face-first into the mud. She starts crying louder as mud had gotten into her eyes. "Steh sofort auf!" ⛧ Angela is grabbed by her hair and shoulder by the guard until she was back on her feet.

Angela cries softly to herself, not wanting to anger him again. She stares up at the pouring rain as she walks, blinking her eyes and trying to get the mud off her face.

The group continues to walk until they reach a courtyard. There, several more men and a priest are waiting for them. Being able to see clearly again, she looks at the horrific display before her. The men were all wearing robes and holding lanterns. The dim light illuminating only a portion of their faces.

Then there was the priest in the middle. He wore a black hat, and black robes. He had a large cross around his neck and a bible in his hands. She looks at his face to see glasses, and crooked teeth. She can’t make out the rest of his face due to the dim lighting, which makes this scene all the more terrifying for the child.

Looking to the men at the left and right of him, she sees that one of them is holding a sword and the other an umbrella. In front of them, is a stone block with a groove on the top of it. At this point it becomes apparent, that this is Angela’s execution day.

One of the guards holds Angela’s shoulders as a signal to stop. One of them steps towards the priest. "Father. We have brought the child for judgement. She was a nuisance to get a hold of."

"Nein! Nein! Bitte lasst mich gehen! Bitte! Jemand muss mir helfen!" ⛧ She screams and desperately struggles in an attempt to free herself. Two of the guards then hold her down onto the muddy earth.

The priest holds out his hand. "Gentlemen, there's no reason to be so hard on this child. Please, let us try to make her last moments as pleasant as possible."

The guards hold Angela back up, firmly but not too harshly. She is still struggling to escape to no avail. They push her towards the priest, and she looks up at her executioner with wide eyes.

Angela flinches as the priest extends his hand to caress her cheek. "My child. I want you to know that I'm very, very sorry. The devil caught you in his claws before God could embrace you with his love. You may not understand it now, but we cannot allow the seed that Lucifer planted to continue to grow. The Lord will understand, I only hope that in your final hour you will as well."

Angela tries to bite the priest’s hand, but he is able to pull away. Her English is rather limited, so she is only able to make out part of what he says. Angry and desperate, Angela speaks whatever comes to her mind to try and save herself.

“Please! You all are crazy! All of you have always been crazy to me and my parents! I am not a devil! Please! Listen to me! I don’t want to die!” She thrashes around trying to undo her binds.

“Dear Lord, it is much worse than what the descriptions said about her. Lucifer has taken over her soul...” The priest looks sorrowful as he holds the crucifix he wore around his neck up to his lips and places a kiss. “The only way to save her soul is to remove the head. Only then will God be able to pass judgement onto her. I’m terribly sorry, but this is the only way to free you from Lucifer’s grasp.”

Angela understood the words of the priest and her heart sank into the pit of her stomach. Completely in shock, she fell limp.

“Du hast Vater gehört! Bringt sie auf den Richtblock ” ⛧ One of the robed men shouted towards the guards holding Angela prisoner. Two guards pick up Angela by the arms and drag her towards the stone block. Angela’s head was placed onto the block with her head turned to the side. Tears ran down her face as she was facing the reality that she was about to die.

The priest opened up his bible and started saying her last rights. “Oh Lord, look upon this child with your grace. The Devil has taken her from the light and now uses her as a pawn for his own blasphemous desires. I humbly ask of you that you show her mercy, by saving her from Lucifer’s hands and taking her into your warm embrace. This young child is too young to understand the grave situation at hand, the fact that she is being used as a root of evil. Lacking a mother and a father, we wish for you to give her a family in the Virgin Mary and our Lord, God. In the name of the Father, The Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

His words fall on deaf ears as the only thing on Angela’s mind is the cold feeling of death that will soon embrace her. She is seeing the reaper right in front of her, extending his hand to take her. Her community failed her. They failed to love her, to take care of her, and to save her. The only thing they have ever brought her is destruction and loss. The loss of her parents, the loss of her innocence, and now the loss of her own life.

One of the robed men hands the priest the sword he was holding. Silently, he raises it up into the air. A sorrowful expression on his face, with hesitation filling his mind as his arm started to tremble. Knowing that he would be the one to deliver this young, horrified child to God filled him with dread. Even so, he knew that the deed had to be done. After all, God has his reasons for everything. No matter how questionable they may seem.

Angela’s mind starts racing with memories. Playing with her father, going to mass and being given hateful looks, being rejected to play with other children, her mother’s warm smile as Angela eats her cooking, her parents yelling in pain from being beaten, the horrific scene of her house on fire, the final moments she last saw her parents, her life on the streets, the warm smile of Mr. Zeigler as she sat next to him by the fire, fighting off creepy people, and finally, her running away as she heard the pained sounds of Mr. Zeigler saving her life.

Angela closes her eyes waiting for what is to come. In her life she has only known pain and loss. Everyone that she loved was forcefully taken away from her. This was her fate, wasn’t it? Decided by God himself, that her life would end this way. She only has one question on her mind...why? Why couldn’t it have been different?

No...No! Her life could not end now! Truly this could not be Angela’s true fate! She was not destined to die like an animal! She would not accept it! She could not accept it! The sword swung down then suddenly...slowed. Angela opens her eyes and shifts her eyes skyward. The sword was still approaching her, but at a snail’s pace. In fact, the rain has slowed down as well. Once her head started pounding it became all to clear to her that this was her power, having come out in her time of need.

She has to make the most of this moment. Her body filled with enough adrenaline to ignore most of the pain coursing through her body. She tries to push herself backwards to no avail as the guard has a grip on her back. But, she notices that the block her head was resting on was rather loose. With all her might, she pushes forward and a small portion of her shirt rips off on her back as she successfully frees herself.

She holds her chest for a moment as the force of landing on top of the block hurt, but then she immediately turns her attention to one of the guards who’s facial expression seemed to change slightly. More importantly than that, he had a knife strapped to his belt.

Angela gets on her feet and darts towards the guard. She uses her teeth to pull out the knife and spat it on the ground. She then sits down to reach it with her hands bound by the rope. With some effort, she is able to cut herself free.

She would not run, though. She was angry. Angry at everyone who’s ever wanted to harm her or her family. Angry that they’ve taken everything from her. It became quite clear to Angela that these people needed to be destroyed.

Angela takes the knife at hand and lunges at the guard she stole it from. She jumps on top of his back and stabs him in the throat, pulling it out and doing the same to the others. One by one the guards and the robed men had blood slowly bleeding out of fatal wounds. The priest is now looking on with a shocked expression on his face; and time stars flowing normally once again.

All the men aside from the priest drop down onto the ground, desperately grabbing at their necks in an futile attempt to save themselves. Angela turns toward the priest as he stares in horror and starts slowly approaching him.

“Y-Young ch-child! W-What have y-you, done!”

“Halt die Klappe!“ ⛧ The priest terrified, ceases talking once she yelled at him. He falls to the ground and Angela stands over him with pure hatred in her eyes.

“P-Please, child. Don’t do this. There is another way! We can go to ask the Lord for forgiveness together! Please!”

Angela gets on top of him and raises her knife. “Then why didn’t you save me?!” She plunges the knife into his chest, swiftly bringing it out and striking him again and again as he screams out in pain.

“Stirb! Stirb! Stirb! Stirb! Stirb! Stirb! Stirb!” ⛧ She screams at the top of her lungs as she does to him what he intended to do to her. Even after he has stopped moving, she brutally keeps mutilating his body out of pure rage for at least a minute longer.

Breathing heavily, she realizes what she has done. She feels no fear over what she’s done though, no remorse, no regret. In fact, she feels triumphant. Being able to deliver the pain she’s experienced tenfold to the people who have treated her so horrible, it strangely makes her feel good inside.

She soon snaps out of it and realizes that she shouldn’t linger around any longer. She takes the knife out of the priest’s corpse and runs off into the opposite direction of the city where she was captured by the guards. She had to hide, then find somewhere else to live out her days.

Angela finds a cave and decides to hide out there for the night. Once she settles down, her adrenaline high leaves her she yells as pain courses through her body. The after effects of her powers that saved her life. This was her cruel fate. She lay down on the cold wet floor, crying. She knew she would not be able to sleep that night. She simply lays and waits for the pain to become bearable enough for her to get back on her feet again and continue her life as a fugitive.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dracula: September 26 - Jonathan and Mina have a nice quiet dinner, while the boys go sneaking into cemeteries

Jonathan Harker's Journal.

26 September.—I thought never to write in this diary again, but the time has come. When I got home last night Mina had supper ready, and when we had supped she told me of Van Helsing's visit, and of her having given him the two diaries copied out, and of how anxious she has been about me. She showed me in the doctor's letter that all I wrote down was true. It seems to have made a new man of me. It was the doubt as to the reality of the whole thing that knocked me over. I felt impotent, and in the dark, and distrustful. But, now that I know, I am not afraid, even of the Count. He has succeeded after all, then, in his design in getting to London, and it was he I saw. He has got younger, and how? Van Helsing is the man to unmask him and hunt him out, if he is anything like what Mina says. We sat late, and talked it all over. Mina is dressing, and I shall call at the hotel in a few minutes and bring him over....

He was, I think, surprised to see me. When I came into the room where he was, and introduced myself, he took me by the shoulder, and turned my face round to the light, and said, after a sharp scrutiny:—

"But Madam Mina told me you were ill, that you had had a shock." It was so funny to hear my wife called "Madam Mina" by this kindly, strong-faced old man. I smiled, and said:—

"I was ill, I have had a shock; but you have cured me already."

"And how?"

"By your letter to Mina last night. I was in doubt, and then everything took a hue of unreality, and I did not know what to trust, even the evidence of my own senses. Not knowing what to trust, I did not know what to do; and so had only to keep on working in what had hitherto been the groove of my life. The groove ceased to avail me, and I mistrusted myself. Doctor, you don't know what it is to doubt everything, even yourself. No, you don't; you couldn't with eyebrows like yours." He seemed pleased, and laughed as he said:—

"So! You are physiognomist. I learn more here with each hour. I am with so much pleasure coming to you to breakfast; and, oh, sir, you will pardon praise from an old man, but you are blessed in your wife." I would listen to him go on praising Mina for a day, so I simply nodded and stood silent.

"She is one of God's women, fashioned by His own hand to show us men and other women that there is a heaven where we can enter, and that its light can be here on earth. So true, so sweet, so noble, so little an egoist—and that, let me tell you, is much in this age, so sceptical and selfish. And you, sir—I have read all the letters to poor Miss Lucy, and some of them speak of you, so I know you since some days from the knowing of others; but I have seen your true self since last night. You will give me your hand, will you not? And let us be friends for all our lives."

We shook hands, and he was so earnest and so kind that it made me quite choky.

"And now," he said, "may I ask you for some more help? I have a great task to do, and at the beginning it is to know. You can help me here. Can you tell me what went before your going to Transylvania? Later on I may ask more help, and of a different kind; but at first this will do."

"Look here, sir," I said, "does what you have to do concern the Count?"

"It does," he said solemnly.

"Then I am with you heart and soul. As you go by the 10:30 train, you will not have time to read them; but I shall get the bundle of papers. You can take them with you and read them in the train."

After breakfast I saw him to the station. When we were parting he said:—

"Perhaps you will come to town if I send to you, and take Madam Mina too."

"We shall both come when you will," I said.

I had got him the morning papers and the London papers of the previous night, and while we were talking at the carriage window, waiting for the train to start, he was turning them over. His eyes suddenly seemed to catch something in one of them, "The Westminster Gazette"—I knew it by the colour—and he grew quite white. He read something intently, groaning to himself: "Mein Gott! Mein Gott! So soon! so soon!" I do not think he remembered me at the moment. Just then the whistle blew, and the train moved off. This recalled him to himself, and he leaned out of the window and waved his hand, calling out: "Love to Madam Mina; I shall write so soon as ever I can."

Dr. Seward's Diary.

26 September.—Truly there is no such thing as finality. Not a week since I said "Finis," and yet here I am starting fresh again, or rather going on with the same record. Until this afternoon I had no cause to think of what is done. Renfield had become, to all intents, as sane as he ever was. He was already well ahead with his fly business; and he had just started in the spider line also; so he had not been of any trouble to me. I had a letter from Arthur, written on Sunday, and from it I gather that he is bearing up wonderfully well. Quincey Morris is with him, and that is much of a help, for he himself is a bubbling well of good spirits. Quincey wrote me a line too, and from him I hear that Arthur is beginning to recover something of his old buoyancy; so as to them all my mind is at rest. As for myself, I was settling down to my work with the enthusiasm which I used to have for it, so that I might fairly have said that the wound which poor Lucy left on me was becoming cicatrised. Everything is, however, now reopened; and what is to be the end God only knows. I have an idea that Van Helsing thinks he knows, too, but he will only let out enough at a time to whet curiosity. He went to Exeter yesterday, and stayed there all night. To-day he came back, and almost bounded into the room at about half-past five o'clock, and thrust last night's "Westminster Gazette" into my hand.

"What do you think of that?" he asked as he stood back and folded his arms.

I looked over the paper, for I really did not know what he meant; but he took it from me and pointed out a paragraph about children being decoyed away at Hampstead. It did not convey much to me, until I reached a passage where it described small punctured wounds on their throats. An idea struck me, and I looked up. "Well?" he said.

"It is like poor Lucy's."

"And what do you make of it?"

"Simply that there is some cause in common. Whatever it was that injured her has injured them." I did not quite understand his answer:—

"That is true indirectly, but not directly."

"How do you mean, Professor?" I asked. I was a little inclined to take his seriousness lightly—for, after all, four days of rest and freedom from burning, harrowing anxiety does help to restore one's spirits—but when I saw his face, it sobered me. Never, even in the midst of our despair about poor Lucy, had he looked more stern.

"Tell me!" I said. "I can hazard no opinion. I do not know what to think, and I have no data on which to found a conjecture."

"Do you mean to tell me, friend John, that you have no suspicion as to what poor Lucy died of; not after all the hints given, not only by events, but by me?"

"Of nervous prostration following on great loss or waste of blood."

"And how the blood lost or waste?" I shook my head. He stepped over and sat down beside me, and went on:—

"You are clever man, friend John; you reason well, and your wit is bold; but you are too prejudiced. You do not let your eyes see nor your ears hear, and that which is outside your daily life is not of account to you. Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are; that some people see things that others cannot? But there are things old and new which must not be contemplate by men's eyes, because they know—or think they know—some things which other men have told them. Ah, it is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all; and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain. But yet we see around us every day the growth of new beliefs, which think themselves new; and which are yet but the old, which pretend to be young—like the fine ladies at the opera. I suppose now you do not believe in corporeal transference. No? Nor in materialisation. No? Nor in astral bodies. No? Nor in the reading of thought. No? Nor in hypnotism——"

"Yes," I said. "Charcot has proved that pretty well." He smiled as he went on: "Then you are satisfied as to it. Yes? And of course then you understand how it act, and can follow the mind of the great Charcot—alas that he is no more!—into the very soul of the patient that he influence. No? Then, friend John, am I to take it that you simply accept fact, and are satisfied to let from premise to conclusion be a blank? No? Then tell me—for I am student of the brain—how you accept the hypnotism and reject the thought reading. Let me tell you, my friend, that there are things done to-day in electrical science which would have been deemed unholy by the very men who discovered electricity—who would themselves not so long before have been burned as wizards. There are always mysteries in life. Why was it that Methuselah lived nine hundred years, and 'Old Parr' one hundred and sixty-nine, and yet that poor Lucy, with four men's blood in her poor veins, could not live even one day? For, had she live one more day, we could have save her. Do you know all the mystery of life and death? Do you know the altogether of comparative anatomy and can say wherefore the qualities of brutes are in some men, and not in others? Can you tell me why, when other spiders die small and soon, that one great spider lived for centuries in the tower of the old Spanish church and grew and grew, till, on descending, he could drink the oil of all the church lamps? Can you tell me why in the Pampas, ay and elsewhere, there are bats that come at night and open the veins of cattle and horses and suck dry their veins; how in some islands of the Western seas there are bats which hang on the trees all day, and those who have seen describe as like giant nuts or pods, and that when the sailors sleep on the deck, because that it is hot, flit down on them, and then—and then in the morning are found dead men, white as even Miss Lucy was?"

"Good God, Professor!" I said, starting up. "Do you mean to tell me that Lucy was bitten by such a bat; and that such a thing is here in London in the nineteenth century?" He waved his hand for silence, and went on:—

"Can you tell me why the tortoise lives more long than generations of men; why the elephant goes on and on till he have seen dynasties; and why the parrot never die only of bite of cat or dog or other complaint? Can you tell me why men believe in all ages and places that there are some few who live on always if they be permit; that there are men and women who cannot die? We all know—because science has vouched for the fact—that there have been toads shut up in rocks for thousands of years, shut in one so small hole that only hold him since the youth of the world. Can you tell me how the Indian fakir can make himself to die and have been buried, and his grave sealed and corn sowed on it, and the corn reaped and be cut and sown and reaped and cut again, and then men come and take away the unbroken seal and that there lie the Indian fakir, not dead, but that rise up and walk amongst them as before?" Here I interrupted him. I was getting bewildered; he so crowded on my mind his list of nature's eccentricities and possible impossibilities that my imagination was getting fired. I had a dim idea that he was teaching me some lesson, as long ago he used to do in his study at Amsterdam; but he used then to tell me the thing, so that I could have the object of thought in mind all the time. But now I was without this help, yet I wanted to follow him, so I said:—

"Professor, let me be your pet student again. Tell me the thesis, so that I may apply your knowledge as you go on. At present I am going in my mind from point to point as a mad man, and not a sane one, follows an idea. I feel like a novice lumbering through a bog in a mist, jumping from one tussock to another in the mere blind effort to move on without knowing where I am going."

"That is good image," he said. "Well, I shall tell you. My thesis is this: I want you to believe."

"To believe what?"

"To believe in things that you cannot. Let me illustrate. I heard once of an American who so defined faith: 'that faculty which enables us to believe things which we know to be untrue.' For one, I follow that man. He meant that we shall have an open mind, and not let a little bit of truth check the rush of a big truth, like a small rock does a railway truck. We get the small truth first. Good! We keep him, and we value him; but all the same we must not let him think himself all the truth in the universe."

"Then you want me not to let some previous conviction injure the receptivity of my mind with regard to some strange matter. Do I read your lesson aright?"

"Ah, you are my favourite pupil still. It is worth to teach you. Now that you are willing to understand, you have taken the first step to understand. You think then that those so small holes in the children's throats were made by the same that made the hole in Miss Lucy?"

"I suppose so." He stood up and said solemnly:—

"Then you are wrong. Oh, would it were so! but alas! no. It is worse, far, far worse."

"In God's name, Professor Van Helsing, what do you mean?" I cried.

He threw himself with a despairing gesture into a chair, and placed his elbows on the table, covering his face with his hands as he spoke:—

"They were made by Miss Lucy!"

DR. SEWARD'S DIARY—continued.

For a while sheer anger mastered me; it was as if he had during her life struck Lucy on the face. I smote the table hard and rose up as I said to him:—

"Dr. Van Helsing, are you mad?" He raised his head and looked at me, and somehow the tenderness of his face calmed me at once. "Would I were!" he said. "Madness were easy to bear compared with truth like this. Oh, my friend, why, think you, did I go so far round, why take so long to tell you so simple a thing? Was it because I hate you and have hated you all my life? Was it because I wished to give you pain? Was it that I wanted, now so late, revenge for that time when you saved my life, and from a fearful death? Ah no!"

"Forgive me," said I. He went on:—

"My friend, it was because I wished to be gentle in the breaking to you, for I know you have loved that so sweet lady. But even yet I do not expect you to believe. It is so hard to accept at once any abstract truth, that we may doubt such to be possible when we have always believed the 'no' of it; it is more hard still to accept so sad a concrete truth, and of such a one as Miss Lucy. To-night I go to prove it. Dare you come with me?"

This staggered me. A man does not like to prove such a truth; Byron excepted from the category, jealousy.

"And prove the very truth he most abhorred."

He saw my hesitation, and spoke:—

"The logic is simple, no madman's logic this time, jumping from tussock to tussock in a misty bog. If it be not true, then proof will be relief; at worst it will not harm. If it be true! Ah, there is the dread; yet very dread should help my cause, for in it is some need of belief. Come, I tell you what I propose: first, that we go off now and see that child in the hospital. Dr. Vincent, of the North Hospital, where the papers say the child is, is friend of mine, and I think of yours since you were in class at Amsterdam. He will let two scientists see his case, if he will not let two friends. We shall tell him nothing, but only that we wish to learn. And then——"

"And then?" He took a key from his pocket and held it up. "And then we spend the night, you and I, in the churchyard where Lucy lies. This is the key that lock the tomb. I had it from the coffin-man to give to Arthur." My heart sank within me, for I felt that there was some fearful ordeal before us. I could do nothing, however, so I plucked up what heart I could and said that we had better hasten, as the afternoon was passing....

We found the child awake. It had had a sleep and taken some food, and altogether was going on well. Dr. Vincent took the bandage from its throat, and showed us the punctures. There was no mistaking the similarity to those which had been on Lucy's throat. They were smaller, and the edges looked fresher; that was all. We asked Vincent to what he attributed them, and he replied that it must have been a bite of some animal, perhaps a rat; but, for his own part, he was inclined to think that it was one of the bats which are so numerous on the northern heights of London. "Out of so many harmless ones," he said, "there may be some wild specimen from the South of a more malignant species. Some sailor may have brought one home, and it managed to escape; or even from the Zoölogical Gardens a young one may have got loose, or one be bred there from a vampire. These things do occur, you know. Only ten days ago a wolf got out, and was, I believe, traced up in this direction. For a week after, the children were playing nothing but Red Riding Hood on the Heath and in every alley in the place until this 'bloofer lady' scare came along, since when it has been quite a gala-time with them. Even this poor little mite, when he woke up to-day, asked the nurse if he might go away. When she asked him why he wanted to go, he said he wanted to play with the 'bloofer lady.'"

"I hope," said Van Helsing, "that when you are sending the child home you will caution its parents to keep strict watch over it. These fancies to stray are most dangerous; and if the child were to remain out another night, it would probably be fatal. But in any case I suppose you will not let it away for some days?"

"Certainly not, not for a week at least; longer if the wound is not healed."

Our visit to the hospital took more time than we had reckoned on, and the sun had dipped before we came out. When Van Helsing saw how dark it was, he said:—

"There is no hurry. It is more late than I thought. Come, let us seek somewhere that we may eat, and then we shall go on our way."

We dined at "Jack Straw's Castle" along with a little crowd of bicyclists and others who were genially noisy. About ten o'clock we started from the inn. It was then very dark, and the scattered lamps made the darkness greater when we were once outside their individual radius. The Professor had evidently noted the road we were to go, for he went on unhesitatingly; but, as for me, I was in quite a mixup as to locality. As we went further, we met fewer and fewer people, till at last we were somewhat surprised when we met even the patrol of horse police going their usual suburban round. At last we reached the wall of the churchyard, which we climbed over. With some little difficulty—for it was very dark, and the whole place seemed so strange to us—we found the Westenra tomb. The Professor took the key, opened the creaky door, and standing back, politely, but quite unconsciously, motioned me to precede him. There was a delicious irony in the offer, in the courtliness of giving preference on such a ghastly occasion. My companion followed me quickly, and cautiously drew the door to, after carefully ascertaining that the lock was a falling, and not a spring, one. In the latter case we should have been in a bad plight. Then he fumbled in his bag, and taking out a matchbox and a piece of candle, proceeded to make a light. The tomb in the day-time, and when wreathed with fresh flowers, had looked grim and gruesome enough; but now, some days afterwards, when the flowers hung lank and dead, their whites turning to rust and their greens to browns; when the spider and the beetle had resumed their accustomed dominance; when time-discoloured stone, and dust-encrusted mortar, and rusty, dank iron, and tarnished brass, and clouded silver-plating gave back the feeble glimmer of a candle, the effect was more miserable and sordid than could have been imagined. It conveyed irresistibly the idea that life—animal life—was not the only thing which could pass away.

Van Helsing went about his work systematically. Holding his candle so that he could read the coffin plates, and so holding it that the sperm dropped in white patches which congealed as they touched the metal, he made assurance of Lucy's coffin. Another search in his bag, and he took out a turnscrew.

"What are you going to do?" I asked.

"To open the coffin. You shall yet be convinced." Straightway he began taking out the screws, and finally lifted off the lid, showing the casing of lead beneath. The sight was almost too much for me. It seemed to be as much an affront to the dead as it would have been to have stripped off her clothing in her sleep whilst living; I actually took hold of his hand to stop him. He only said: "You shall see," and again fumbling in his bag, took out a tiny fret-saw. Striking the turnscrew through the lead with a swift downward stab, which made me wince, he made a small hole, which was, however, big enough to admit the point of the saw. I had expected a rush of gas from the week-old corpse. We doctors, who have had to study our dangers, have to become accustomed to such things, and I drew back towards the door. But the Professor never stopped for a moment; he sawed down a couple of feet along one side of the lead coffin, and then across, and down the other side. Taking the edge of the loose flange, he bent it back towards the foot of the coffin, and holding up the candle into the aperture, motioned to me to look.

I drew near and looked. The coffin was empty.

It was certainly a surprise to me, and gave me a considerable shock, but Van Helsing was unmoved. He was now more sure than ever of his ground, and so emboldened to proceed in his task. "Are you satisfied now, friend John?" he asked.

I felt all the dogged argumentativeness of my nature awake within me as I answered him:—

"I am satisfied that Lucy's body is not in that coffin; but that only proves one thing."

"And what is that, friend John?"

"That it is not there."

"That is good logic," he said, "so far as it goes. But how do you—how can you—account for it not being there?"

"Perhaps a body-snatcher," I suggested. "Some of the undertaker's people may have stolen it." I felt that I was speaking folly, and yet it was the only real cause which I could suggest. The Professor sighed. "Ah well!" he said, "we must have more proof. Come with me."

He put on the coffin-lid again, gathered up all his things and placed them in the bag, blew out the light, and placed the candle also in the bag. We opened the door, and went out. Behind us he closed the door and locked it. He handed me the key, saying: "Will you keep it? You had better be assured." I laughed—it was not a very cheerful laugh, I am bound to say—as I motioned him to keep it. "A key is nothing," I said; "there may be duplicates; and anyhow it is not difficult to pick a lock of that kind." He said nothing, but put the key in his pocket. Then he told me to watch at one side of the churchyard whilst he would watch at the other. I took up my place behind a yew-tree, and I saw his dark figure move until the intervening headstones and trees hid it from my sight.

It was a lonely vigil. Just after I had taken my place I heard a distant clock strike twelve, and in time came one and two. I was chilled and unnerved, and angry with the Professor for taking me on such an errand and with myself for coming. I was too cold and too sleepy to be keenly observant, and not sleepy enough to betray my trust so altogether I had a dreary, miserable time.

Suddenly, as I turned round, I thought I saw something like a white streak, moving between two dark yew-trees at the side of the churchyard farthest from the tomb; at the same time a dark mass moved from the Professor's side of the ground, and hurriedly went towards it. Then I too moved; but I had to go round headstones and railed-off tombs, and I stumbled over graves. The sky was overcast, and somewhere far off an early cock crew. A little way off, beyond a line of scattered juniper-trees, which marked the pathway to the church, a white, dim figure flitted in the direction of the tomb. The tomb itself was hidden by trees, and I could not see where the figure disappeared. I heard the rustle of actual movement where I had first seen the white figure, and coming over, found the Professor holding in his arms a tiny child. When he saw me he held it out to me, and said:—

"Are you satisfied now?"

"No," I said, in a way that I felt was aggressive.

"Do you not see the child?"

"Yes, it is a child, but who brought it here? And is it wounded?" I asked.

"We shall see," said the Professor, and with one impulse we took our way out of the churchyard, he carrying the sleeping child.

When we had got some little distance away, we went into a clump of trees, and struck a match, and looked at the child's throat. It was without a scratch or scar of any kind.

"Was I right?" I asked triumphantly.

"We were just in time," said the Professor thankfully.

We had now to decide what we were to do with the child, and so consulted about it. If we were to take it to a police-station we should have to give some account of our movements during the night; at least, we should have had to make some statement as to how we had come to find the child. So finally we decided that we would take it to the Heath, and when we heard a policeman coming, would leave it where he could not fail to find it; we would then seek our way home as quickly as we could. All fell out well. At the edge of Hampstead Heath we heard a policeman's heavy tramp, and laying the child on the pathway, we waited and watched until he saw it as he flashed his lantern to and fro. We heard his exclamation of astonishment, and then we went away silently. By good chance we got a cab near the "Spaniards," and drove to town.

I cannot sleep, so I make this entry. But I must try to get a few hours' sleep, as Van Helsing is to call for me at noon. He insists that I shall go with him on another expedition.

----

Original Substack Post

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jonathan Harker's Journal---continued

He was, I think, surprised to see me. When I came into the room where he was, and introduced myself, he took me by the shoulder, and turned my face round to the light, and said, after a sharp scrutiny:---

"But Madam Mina told me you were ill, that you had had a shock." It was so funny to hear my wife called "Madam Mina" by this kindly, strong-faced old man. I smiled, and said:---

"I was ill, I have had a shock; but you have cured me already."

"And how?"