#pygostyle

Text

Tributo a Claudia Hotwife

Taboo teenager riding forbidden cock after hj

hard rock casino tampa players club

Sex tape of a real amateur couple watching porn together - Cherry Mobile

Exhibitionists at Bear Creek Park

Melly, une blonde sexy qui aime le sexe

Fresh ebony girl webcam porn

Tight Latina cutie Megan Martinez sucks dick then takes a hard cock in her pussy

Poliana chupando muito no DF

DOCEAN Marica Hase Rimming and Black Bull Breeding

#anti-Plato#consignable#billionaire#bromisms#seafighter#pygostyle#Orma#horsing#tempest-walking#augurer#digynous#Punchinelloes#halophilous#tenoner#misreported#pseudodemocratically#cytogeneticist#first-expressed#closest#tertial

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Famous Massage Parlor

Real amateurs sucking

Aquele boquete gostoso no boy

madre soltera puta mexicana sexo por dinero

Rebolando no pau do parceiro de foda

Straight canadian handsome boys gay sex nude teen sucking cock xxx

KATHY DM

bucetuda linda

Filming black teen slut riding my dick

Naked men gay porn xxx movieture You Broke? Hop On The BaitBus

#amorphy#pygostylous#halazones#anterofixation#outbear#hastens#urbanists#reexposure#majas#paradoxidian#unappoint#concentring#chastisable#day-fever#abirritated#seltzogene#manor-house#subtartarean#Terrier#aero

0 notes

Note

Are frogs birds?

No, birds belong to the group of sarcopterygian fish that have keratinised structures embedded in their skin and have modified their eggs to contain a structure called an amnion, and have some caudal vertebrae modified into a solidified structure called a pygostyle. Frogs belong to the group of sarcopterygian fish that lack keratin in their skin and lay anamniotic eggs, but have enhanced cutaneous respiration, and all their caudal vertebrae modified into a solidified rod called a urostyle.

#I guess there are a couple other differences as well#but these are at least a start#birds#frogs#answers by Mark#anon#anonymous

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danielsraptor vs Heracles

Factfiles:

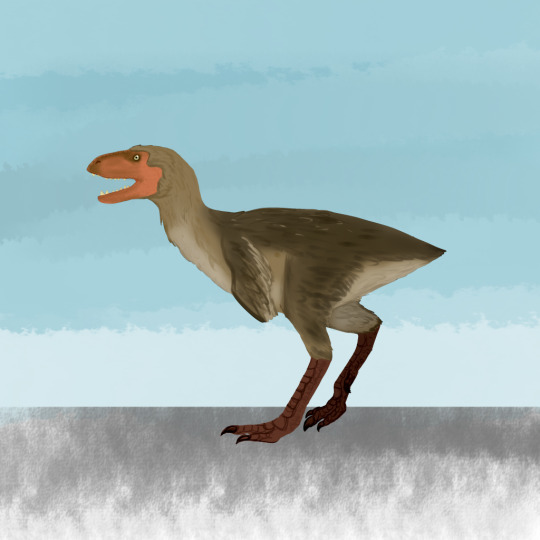

Danielsraptor phorusrhacoides

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Michael Daniels’ Terror Thief Bird

Time: 55 million years ago (Ypresian stage of the Eocene epoch, Paleogene period)

Location: Walton Member, London Clay Formation, England

While the Eocene fossil records of Seriemas, Passerines, and Parrots are fairly well known, the last remaining group of Australavians - the Falcons - remains something of a mystery. Danielsraptor helps to put together this puzzle a little more. Along with Masillaraptor, these birds show an early radiation of falcon-relatives from the Eocene in which they tried out a more terrestrial lifestyle! Danielsraptor had long legs, allowing it to forage and hunt on the ground like modern caracaras. It had a very large pygostyle, giving it long tail feathers - and with strong wing bones, it was able to fly in addition to hunt on the ground. It had a beak very similar to living caracaras and the extinct Terror Birds, further corroborating the idea that it was a bird of prey (and also potentially indicating a more complex evolutionary story for the early-derived Australavians). Living in the London Clay, Danielsraptor would have been one of the top predators, easily hunting the small mammals as well as the birds it shared its environment with - aided by both its terrestrial stalking abilities as well as its flying capability. Living in the London Clay, it shared its environment with the early loon Nasidytes, early owls, trogons, paleognaths, tropicbirds, duck-screamers, other diurnal raptors, the pseudotoothed bird Dasornis, and many parrot-passerine relatives. Crocodilians, snakes, turtles, fish, sharks, and a handful of mammals (including a primate) also lived in this rich post-Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum environment.

Heracles inexpectatus

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Unexpected Herculean Parrot

Time: 16 to 19 million years ago (Burdigalian stage of the Miocene epoch, Neogene period)

Location: St. Bathans Fauna, Bannockburn Formation, Aotearoa

Heracles was a truly alarmingly large parrot, related to modern day Kea, Kaka, and Kakapo, known from the fantastic avifauna of St Bathans. Standing more than two feet tall and weighing about fifteen pounds, this animal was much larger than any expected from the St Bathans fauna, which represented the initial colonization of Aotearoa (Zealandia) after it returned above sea level. Heracles is also the largest known species of parrot, ever. It was presumably flightless, though it is uncertain if it was nocturnal like its living relative the Kakapo. Its exact ecology is still uncertain, given the material known from Heracles is limited and its living relatives have very disparate ecologies, though it is possible it was omnivorous similar to the Kea and Kaka today. The St Bathans fauna lived in a freshwater lake system, in a subtropical emergent rainforest. Separated from land bridges, the fauna was dominated by birds, with early relatives of the Kiwi, New Zealand Wrens, Adzebills, and Wedge-Tailed eagles found in the fauna, as well as somewhat modern looking Moas. Smaller flamingos, large fruit pigeons, and a huge variety of geese and other waterfowl are known. In addition, frogs, tuataras, other lizards, crocodilians, turtles, and many different types of fish are known from this fascinating ecosystem.

DMM Round One Masterpost

#dmm#dinosaur march madness#dmm round one#dmm rising stars#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#paleontology#bracket#march madness#danielsraptor#heracles#polls

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enantiornithean Earth

Yungavolucris and Halimornis by midiaou and xenopleurodon respectively. Both are real life Cretaceous taxa, showing that these birds were already diversifying into aquatic ecologies.

Enantiornithes are a group of extinct flying theropod dinosaurs that you could reasonably call birds, being the sister group of Euornithes (the group that includes modern birds). However, they differ from our birds in a variety of ways (their name literally means “opposite birds” for a reason):

Several skeletal details, including a tarsometatarsus that is either unfused or half-fused (beginning at the top rather than at the bottom, the opposite than in modern birds), an articulation of the scapula and coracoid that is oppositely shaped (hence the name; the coracoid joint is convex and the scapula joint is concave shaped in enantiornitheans, while the opposite happens in modern birds), a shallower sternum keel with bizarre antler-like projections (which, combined with large crests in their humerus, suggests the muscles lifting the wing were attached to the back as in bats and pterosaurs, rather than all flight muscles being attached to the keel as in modern birds), and a large, rod-shaped pygostyle (which will be relevant later).

Usually toothed jaws instead of beaks, though some taxa did become toothless. Even then, these weren’t capable of cranial kinesis like modern birds (i.e. watch a duck or your pet parrot yawn and you can see them moving their upper jaw; enantiornitheanss are many things but they’re not that abominatory).

All known taxa thus far seem to have been superprecocial: ample sites show buried eggs like those of megapodes, and the hatchlings were already fully flight capable soon after birth.

Unlike modern birds, enantiornitheans lacked a tail fan. They either had contour feathers on their butt like in the rest of the body or had long, streamer-like display feathers, also found in other Cretaceous bird groups but not in modern birds. Some species did have retrices, but they were arranged along the rod-like pygostyle and were not a movable fan, so essentially they were a variation of the tail fronds seen in Archaeopteryx and kin. Note that this did not make flight harder; even modern birds can fly reasonably well without a tail.

Why the opposite birds died out at the end of the Mesozoic while ours survived is unclear. Often, a bias towards arboreal niches is cited, as many enantiornitheans were in fact arboreal, but as the examples above show they also occured in marine and terrestrial niches alongside the ancestors of modern birds. Another possibility is their supreprecocial habits, meaning a more complex ecology as the birds matured since they were already functionally independent since birth, and this did hinder reptiles like lizards so the answer might lay there.

Or, most likely, it was just dumb luck.

Anyways:

Senmuruy hvare by Dave García. A four meter wingspan predator vaguely analogous to the golden eagle and cinnereous vulture, soaring across the northern hemisphere for corpses to dig its long snout into or live mammals and birds to sink its talons into.

Many Cretaceous enantiornitheans were already suspected of being raptorial, so it is only natural that, once pterosaurs were gone, they’d increase in size. Some reach wingspans of fiver meters, but most are more moderately sized at 1.5-3 meter adult wingspans. Smaller sizes are handled by the young, which like all enantiornithes can already fly since birth and occupy distinct ecological niches. Most species protect the nest and moderate its temperature like our megapodes, and a few even display mild parental care, allowing the young to remain in the vicinity until they’re large enough to be competition.

Euodontopteryx anatosuchus, a six-meter wingspan pelagic soarer that occurs in tropical and temperate waters, using its massive wings to ride on thermals like frigatebirds while landing to feed like albatrosses. Males sport streamer-like display feathers. By Dave García.

As noted above, some Cretaceous enantiornitheans were already aquatic, so this trend continued. Some species became divers, mostly wing propelled and some even flightless like our penguins, while others inversely invested in supreme gliding abilities, able to either ride thermals like frigatebirds or wave winds like albatrosses.

The most impressive species are reccord beaters. Divers can be as tall as a man when on land, while soarers can reach wingspans of over 7 meters, competing with flying multituberculates for largest living flying animals. Both groups tend to have long, toothy maws, the teeth alloted into a single row rather than individual sockets; this condition is known in both extinct sea birds and reptiles as well as some living cetaceans, and is known as aulacodonty.

Ghaltavis rex, a three meter tall predator that stalks African and Asian savannas. An apex predator of its own right, an echo of the distant unrelated tyrannosaurs in the form of a bird. By Dave García.

At least one real life enantiornithean, Elsornis, appears to have been flightless. It’s descendents were quick to occupy roles previously taken by non-avian theropods, from ratite-like herbivores to formidable predators that look like the fusion of a terror bird and a tyrannosaur, using their powerful jaws to crush bone.

The relatively long enantiornithean pygostyle allowed them to balance their pelvis/femur joints (a known size inhibittor in our birds) and grow to sizes larger than our timeline’s birds, though species above a ton are fairly rare seeing as mammals got their footing as well.

Bennu seti, a filter-feeding bird from Africa, Eurasia and Australia. Like flamingos it metabolizes carotenoids, giving it an orange colouration. By Dave García.

The Cretaceous Lectavis had long legs in some aspects convergent with those of flamingos. Thus, several enantiornitheans developed wading ecologies, ironically more associated with their euornithean competitors. Some became probers, dipping their maws (or toothless beaks) into the subtrate, while others became piscivores like herons or aquatic plant specialists like some cranes and magpie geese.

Most spectacular is a filter-feeding clade, Bennuidae. These birds modified their teeth into thin, delicate strands like some Cretaceous pterosaurs, and feed by swallowing water and expelling it, trapping prey in the teeth and keratinous spikes in the tongue. Having the nostrils still at the end of the snout, these birds usually feed in a different position from flamingos: rather than upside down, the lower jaw is submerged, in a manner similar to avocets.

Like most opposite birds the young are superprecocial, starting as plover-like birds before transitioning into a filter feeding lifestyle months later. Though some taxa form protective creches like flamingos, though unlike them they do not feed the young.

Like many of our shorebirds, these are continuous flappers, displaying remarkable endurance as they fly non-top for days in their migrations.

#enantiornithes#enantiornithean#enatiornithine#bird#birds#dinosaur#dinosaurs#paleoblr#palaeoblr#speculative zoology#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love ur raptor designs!!! How are they compared to birds as we know them? and would it be okay to make a raptor character in ur style? if not, no problem! just wanted to check before trying to design one.

thank you, they are more like modern birds which have teeth and don't have a pygostyle (bone that causes the tail to be shorter). evidence indicates that theropods had hollow bones like birds, and they may have also had respiratory systems more like birds than the mammalian lung system we are more familiar with. they're surprisingly similar, but the raptor-birds in idletry are anthropomorphic, so their biology takes a lot of liberties.

i know that they aren't capable of flight, as the heaviest birds we know of that are capable of it cap out at 50 lbs, but they may have professional sports akin to gymnastics where they try to glide as far as possible with athleticism.

anyway, go ahead and make one in the style if you'd like. i'm annoyed that i haven't done so myself, so it kind of just looks like only this blue jay is like that, when it's supposed to be all birds--

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I haven’t done any anatomy stuff in a long time, so I decided to challenge myself with a creature design project combining eagle and whale anatomy. The result is what I call a wheagle - not the greatest name, but I started calling it that way back at the beginning of this project and it kind of stuck lol.

Since I’m still pretty rusty with anatomy, I gave this animal a fairly conservative and recognizable avian body - for the most part. The head, talons and tail are where the whale anatomy comes into play. The elongated skull displays telescoping (a reduced distance between the maxilla and occipital), resulting in dorsally located, blowhole-like nostrils. There is also a melon organ (pictured in the muscle study), a mass of tissue on the dorsal snout that aids in echolocation. The tusks were inspired by beaked whales, and are only found in the male animal. All in all the skull components are more mammalian than avian, despite the eagle-like beak and eyes.

The long, muscular tail was likewise inspired by cetacean muscle/locomotion, but ends in a pygostyle/tail fan that functions the same as in birds. There are five talons instead of four, but the outer fifth talon is basically vestigial - I only added it as a nod to the five “fingers” within whale flippers.

The wheagle is a fairly large piscivorous animal native to the South Pole. It feeds mainly on deep sea icefish, which it hunts using echolocation. Color scheme is inspired by African fish eagles. I’ll have some more studies of this creature’s anatomy to share later on; I definitely enjoyed getting back into animal anatomy and creature design!

#creature design#bird creature#creature anatomy#bird anatomy#whale anatomy#cetacean anatomy#creature art#concept art#skeleton#musculature#beaked whale#ziphiidae#eagle#african fish eagle#bones#muscles#anatomy#animal anatomy#digital art

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oviraptor is an extinct genus of oviraptorid dinosaur that lived throughout what is now Mongolia during the Campanian and Maastrichtian Stages of the Cretaceous period some 78 to 70 M.Y.A. The first remains of Oviraptor consisting of a mostly complete skeleton with a badly crushed skull which was found lying over a nest of approximately 15 eggs were unearthed from reddish sandstones of the Late Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia in 1923 by a North American paleontology expedition led by Roy Chapman Andrews. This specimen would be formally named and described a year later by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1924. Because the skull of the specimen was separated from the eggs by only 10 cm of sediment Osborn interpreted Oviraptor as a dinosaur with egg-eating habits, naming the animal Oviraptor which is Latin for "egg seizer" or "egg thief”. The specific name, philoceratops, is intended as "fondness for ceratopsian eggs" which is also given as a result of the initial thought of the nest pertaining to Protoceratops or another ceratopsian. However in the 1990s, the discovery of numerous additional specimens including nesting and nestling oviraptor specimens proved that the initial specimen wasn’t an oviraptor stealing the eggs of another dinosaur, but instead it was a mother oviraptor trying to protect her own nest from a sandstorm. Reaching around 5-6ft in length, 2.5 to 3.5ft tall, and 70-90lbs in weight, oviraptor was a bipedal creature which sported a short, curved, toothless beak and prominent head crest. It had a covering of feathers over its entire body and a pygostyle: several fused vertebrae at the base of the tail that in modern birds is used as a support for tail feathers. With the egg stealing idea now debunked it is believed oviraptor had a much more diverse omnivorous diet comprised of leaves, berries, fruit, nuts, seeds, mollusks, worms, small vertebrates, insects, crustaceans, and other arthropods.

Art work links:

https://twitter.com/Cynderen/status/1486132223833260038/photo/1

http://novataxa.blogspot.com/2020/12/oviraptorosaur.html

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/564920347004490660/

https://nathan-e-rogers.tumblr.com/post/648194189622935552/oviraptorid-adult-and-chicks-late-cretaceous

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is the best bone?

I can't pick just one! And are we talking human or animal? I'm partial to a good vertebrae--so many pieces, so intricate, like a puzzle. But you can learn so much from a pelvis, people always think about the skull--and the skull is great--but I believe you can learn so much from the pelvis; the shape and function of the animal. Yes, perhaps you can deduce sex of the creature from the skull, but you really see it in the pelvis.

Oh but not to say the other bones are bad! Oh, but maybe my answer is the vertebrae. I just found the caudal vertebrae of a chicken (complete with the pygostyle) and I'm very excited about that.

No! I couldn't possibly choose. Don't make me choose.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first Early Cretaceous bird outside China, and the earliest example of a 'true' pygostyle. The pygostyle is a bird's 'tailbone'.

Fukuipteryx prima

('Fukui feather/wing, first')

Theropoda Avialae

Kitadani Formation, Fukui Prefecture, Honshu, Japan.

Lower Cretaceous, ~120 Ma.

~

Artwork by Raul Martin.

Daily Dino Fact #44

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

To lose weight so birds could take to the air, the beak replaced heavy teeth and many bones fused together or were completely lost. Some thoracic vertebrae melded, eliminating some individual bones and stiffening the back to support the flight muscles. The lumbar, sacral, and some caudal vertebrae fused with the bones of the pelvis, forming a structure called the synsacrum. This construction stiffens the dorsal skeleton, strengthening the entire body to withstand the stresses of flight and landing. The rest of the caudal vertebrae fused into the pygostyle —it is sometimes called the “pope’s nose”—a short bony structure that is covered by muscle and skin and to which the tail feathers are attached. With a rigid skeleton and wings that are pretty much restricted to locomotion, birds need flexible necks to move their head for essential everyday functions like feeding, eating, and nest construction.

Some bones of the “hand” (outer part of the wing) have been lost or fused, leaving only three digits instead of the typical five found in most land vertebrates. The “thumb” supports the alula or bastard wing, a small but important structure in flight. A number of bones in the toes and legs are fused or have been lost. A bird actually walks on its toes and what appears to be a backward-facing knee is the metatarsus bone, essentially an elongated ankle. The major flight muscles, those providing power, are attached to a ventral extension of the sternum or breastbone, the carina. When we carve a Thanksgiving turkey, we usually start by slicing pieces of the side of the breast, making a pile of white meat out of the two major flight muscles, eventually exposing the carina. The sternum is braced by the wishbone or furcula. As the flight muscles compress the thorax during the downstroke, the furcula bends, absorbing some of the stress to the skeleton; on the upstroke, the furcula expands, helping a bit in moving the wings upward.

Dropping weight is also achieved by the reduction of internal organs and seasonal physiological changes. Most female birds (with exceptions like the kiwi) have only a left ovary and oviduct, which shrink noticeably during the non-breeding season. The male’s testes are tiny during the non-breeding season and may enlarge by as much as 300 times when the nesting season commences—at this point the birds are not migrating so they can afford a bit more weight. Except for the Ostrich, birds do not have a bladder. Carrying water only makes birds heavy, so instead of producing watery urine, their nitrogenous waste is in the form of a white paste of insoluble uric acid, which contains only about 5 percent water. When drinking nectar, hummingbirds take on a lot of water and thus weight. To reduce the amount of water they carry, they transpire some of it from their respiratory system—huffing and puffing 250 times per minute—and remove the rest via their very efficient kidneys. A typical hummingbird, in fact, will eliminate twice its weight in water every day.

The color of some feathers plays a surprisingly important role in flight. The pigment melanin, which produces brown and black colors, increases the resistance of feathers against abrasion from the turbulent air around the wingtips, airborne particles, the wear caused by feathers rubbing against each other, and degradation by feather bacteria. This is why many large birds (Snow Geese, White Pelicans, the European White Stork, and some gulls and terns) have black or dark wingtips, or totally black wings (like frigatebirds and murres).

0 notes

Text

cube

You don’t have to be mortal, enemy or otherwise … being and nothingness is plenty

2

a distorted reflection on water sharper than any physical presence rewards me in spite of my hopelessness.

3

I don't know if it is too late to inherit exactly what I grieve,

4

gone before I scrape out the angelic scion and explore the heartless cache of his boyhood [nursery] gone before I attempt to disambiguate the mess we learned. Picking a pygostyle bone from aleatory air, landing a soft double-six, a souvenir from his mother, on my palm. Another six in number we’d have a magic square.

a three-tiered vanity mirror to sit undesired before and cry to a stranger in this room, on this chair.

unfinished f i r s t draft

0 notes

Photo

Whiskers for deinonychus

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seeleyosaurus guilelmiimperatoris here was a smallish plesiosaur (about 3.5m long / 11'6") found in Germany during the early Jurassic, about 182 million years ago.

And back in the 1890s, a specimen of this species was discovered with soft tissue impressions showing a diamond-shaped tail fin.

But despite us knowing about plesiosaur tail flukes for such a long time, they're surprisingly under-represented in reconstructions, never seeming to have become associated with the popular image of these animals in the same way that early pterosaur's tail vanes did. It doesn't help that no other direct impressions of plesiosaur tail fins have ever been found, or that the Seeleyosaurus specimen's soft tissue got painted over at some point in the mid-1900s, making it incredibly difficult to study without causing further damage.

(Perhaps modern non-invasive scanning techniques could be able to see under the paintjob, but as far as I'm aware nobody's tried that yet.)

These tail fins are usually assumed to have been vertically oriented like those of other aquatic reptiles, moving side-to-side and acting like a rudder. However, there's also a hypothesis that their fins might have actually been horizontal more like those of modern cetaceans and sirenians, based on several anatomical quirks – such as their tail regions being very wide and flat at the base, and the vertebrae at the tip being unusually pygostyle-like, very different from the way the tail bones of vertically-finned reptiles look.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#seeleyosaurus#microcleididae#plesiosaur#sauropterygia#pantestudines#archosauromorpha#reptile#marine reptile#art#chub-blubs#yeah let's just PAINT OVER the only plesiosaur tail fin impression ever found#it's not important or anything#😒

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

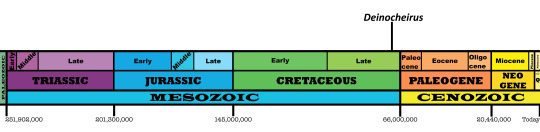

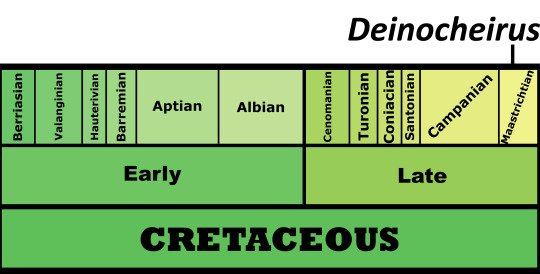

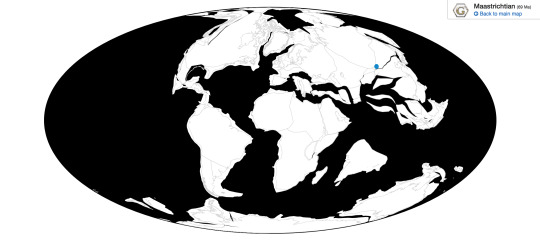

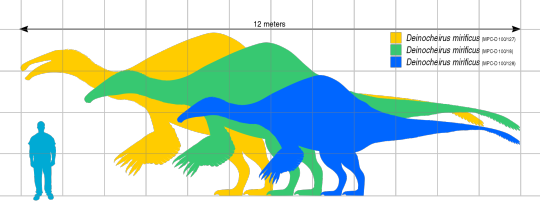

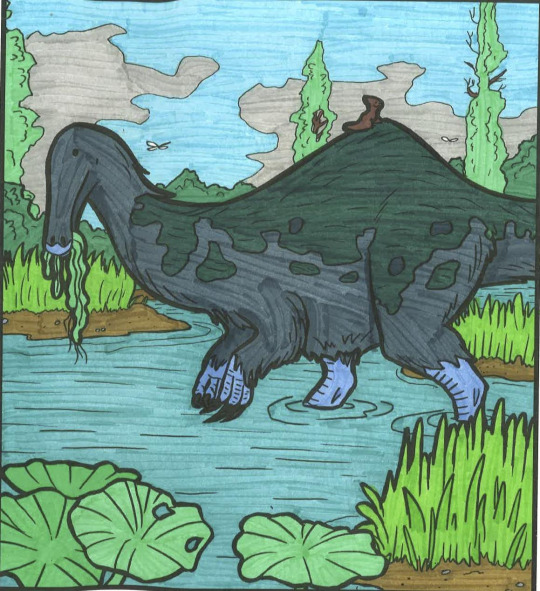

Deinocheirus mirificus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Horrible Hand

First Described By: Osmólska & Roniewicz, 1970

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Ornithomimosauria, Ornithomimoidea, Deinocheiridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 70 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

Deinocheirus is known from the Nemegt Formation of Ömnögovi, Mongolia

Physical Description: Deinocheirus is one of the absolute weirdest, fantastical, most surprising discoveries of the 2010s in paleontology, and the answer to a mystery older than most of the readers of this blog. Deinocheirus was originally known from two very long, distinctive arms - arms so long, that they could very easily engulf a person. In fact, many of the photographs of the fossil are of an individual standing in between the hands, in order to give scale to them. But these arms and hands gave very little in the way of information about what Deinocheirus looked like. Eventually, it was determined that Deinocheirus was an Ornithomimosaur - but the scale of the arms indicated it would be a ridiculously huge Ornithomimosaur.

By Slate Weasel, in the Public Domain

And then, luckily, more fossils were found of it. To be sure, it was a ridiculously large Ornithomimosaur - in fact, given the fact that it was an Ornithomimosaur, a group of distinctively feathered dinosaurs, it is almost certainly one of the largest feathered animals known to date - but it was More than that by a large margin. It was probably around 11 meters long, weighing up to 6.4 tonnes. It had some of the largest forelimbs known of any bipedal dinosaur - only rivaled by Therizinosaurs - and the arms in question are 2.4 meters long. Its skull, only one specimen of it having been found, is honestly weirdly duck-shaped. It was low and narrow, like other Ornithomimosaurs, but with a longer snout than its relatives. This snout was wide and shaped like a spatula - similar to the snouts of duck-billed dinosaurs and ducks alike. There weren’t any teeth in the jaws, which ended in a distinctive beak, and it was turned down, to make it look fairly massive and deep. When you get down to it, Deinocheirus had a ridiculously triangular head.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

As for the rest of the body, Deinocheirus had very long and narrow shoulder blades, connected to very pronounced and triangular shoulders. Weirdly enough, compared to the shoulders, Deinocheirus actually had smaller arms than its close relative Ornithomimus - ie, it had a smaller shoulder to arm ratio than its relatives. It had a U-shaped wishbone, which is fascinating since we don’t have the wishbone of other Ornithomimosaurs. Unlike other Ornithomimosaurs, it didn’t have pinched toe bones, so it wasn’t highly adapted for fast movement; it also had very blunt and broad foot claws like those of large Ornithischian dinosaurs. It may have been a bulky animal, but it was also quite narrow - with very tall, straight ribs. It had an S-curved neck, especially given the shape of the skull, which extended back into the oddly indeed shaped back. The spines on the back of Deinocheirus got progressively and progressively longer, until reaching lengths similar to those found on Spinosaurus - indicating that Deinocheirus had a sail or a hump, much like Spinosaurus did. There were interconnecting ligaments on the spines, strengthening it. That sail then lessened as it went down along the tail, until the tail had a very skinny appearance compared to the rest of the body. It had extremely lightweight air bones, through which the respiratory system ran. This also allowed it to be even more lightly built, which aided it in its large size. Interestingly enough, the tail ended in fused vertebrae, like those in Therizinosaurs, Oviraptors, and Birds - indicating it had a pygostyle!

By Michael B. H., CC BY-SA 3.0

As for feathers, it would have probably been covered in a layer of fluff all over the body. Fancy, pennaceous feathers would have been present on the arms and the end of the tail - in fact, a tail fan would have been attached to that pygostyle and used in display. It may have also had display feathers on the back of the head or even the legs. However, that being said, its large size may indicate a decrease in fluff so that it could stay cool - while it is still most likely that it had distinctive and extensive feathers as in its close relatives, fossil evidence is needed to determine its exact integument situation.

By Charles Nye

Diet: Deinocheirus was, distinctively, a large herbivore - specializing on water plants and other soft greens that could be shoveled up with that spoon beak.

By Meig Dickson & Diane Remic

Behavior: Deinocheirus probably spent a good amount of time foraging at or near the water, gathering up water vegetation with its spatulate bill. It also utilized gastroliths - stones that were swallowed to grind up that wet and mushy vegetation in the stomach. This was important and helpful, since it couldn’t do much grinding without teeth in its mouth. It did have a very long and large tongue, which allowed it to pull up extensive amounts of plant material up from the ground. It would use the blunt and short claws of its hands in order to dig up plants from the water - and to decrease resistance as it sucked them up from the swamps.

By Rebecca Groom

Deinocheirus wasn’t a fast animal - the short and stocky legs meant that it moved slowly through its environment, and used its large size to protect itself against predators instead. It grew extremely rapidly, too, reaching large size before sexual maturity. Sadly, its giant size means that it didn’t have a very large brain compared to its body size - in fact, the ratio in question was more similar to that of sauropods than other theropods. That beings aid, it was similar in shape to birds and troodontids and other birdie theropods, indicating that it still had a decent sense of smell - which is fascinating as it had a good respiratory system as well. As a warm-blooded animal, however, it would have been very active; and as a dinosaur, it probably took care of its young in nests. It is uncertain whether or not it would have lived in social groups, but it certainly wouldn’t have been particularly isolated as an herbivore.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Nemegt Formation was a wetland, filled with a wide variety of dinosaurs right before the end of the time of non-avian dinosaurs. The area was filled with large river channels, which created extensive shallow lakes, mudflats, and floodplains - like the modern Okavango Delta in Botswana. There were also thick coniferous forests surrounding the ecosystem, allowing for drier areas to be retreated to in addition to the swampy mess that was the bulk of the environment. Here, many plant-eaters specialized in feeding on water plants - in fact, I often joke that the Nemegt is the Land of Ducks. In addition to Deinocheirus, there were two other Ornithomimosaurs - Gallimimus and Anserimimus - both featuring duck-like beaks for feeding on water plants. Other ducks of the region include Saurolophus, which, as a duck-billed dinosaur, was especially adapted for feeding on soft plant material; and Teviornis, an early ACTUAL duck relative with the appropriate bill.

By Fraizer

This place also had other dinosaurs that weren’t ducks, of course. There was the large tyrannosaur, Tarbosaurus, which is known to have directly preyed upon Deinocheirus. There were troodontids too, like Tochisaurus, Zanabazar and Borogovia, which would have preyed upon the eggs and young of Gallimimus. There were a million different Oviraptorosaurs, making this also the ecosystem of the Chickenparrots - Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Conchoraptor, Nemegtomaia, Nomingia, and Rinchenia, were all present and feeding on the drier vegetation of the area. There was also the Hesperornithine Brodavis, one of the few freshwater species of Hesperornithines. There were other herbivores too, of course - Pachycephalosaurs like Homalocephale and Prenocephale, ankylosaurs such as Tarchia and Saichania, the titanosaur Nemegtosaurus, and the Therizinosaur Therizinosaurus - which probably all stuck to drier areas of the ecosystem than Deinocheirus. Tarbosaurus wasn’t the only Tyrannosaur, either - there was the smaller Alioramus which would have been more of a nuisance for baby Deinocheirus than the adults. And for other predators, there was the raptor Adasaurus, which may or may not have been a direct descendant of Velociraptor. As for non-dinosaurs, there was at least one Azdarchid, the small mammal Buginbaatar, and a variety of crocodilians that would have been non-negligible threats to young Deinocheirus. There were also plenty of turtles, which would have been a very noticeable part of the wider ecosystem.

By Scott Reid

Other: Deinocheirus is such a weird Ornithomimosaur, it gave its name to an entire group of them - these guys were slower than the Ornithomimids, and larger, but still had that general Ostrich-mimic shape. Instead of being lean and fast, they were large and slow. The discovery of the specimens of Deinocheirus that allowed us to actually learn what it looked like was a big one - since, prior to that point, Deinocheirus had been one of the most fascinating mysteries of dinosaur science, as all we had were two giant hands! Because of its large size, duck-like appearance, and above all, nightmare fodder in terms of past legend and current appearance, Deinocheirus has been fondly dubbed as Duck Satan for a makeshift common name.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Arbour, V. M., Currie, P. J. and Badamgarav, D. (2014), The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 172: 631–652.

Barret, P. M. 2005. The diet of Ostrich dinosaurs (Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria). Palaeontology 48 (2): 347 - 358.

Barsbold, R. (1983). "Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia [in Russian]." Trudy, Sovmestnaâ Sovetsko−Mongol’skaâ paleontologičeskaâ èkspediciâ, 19: 1–120.

Bell, P.R., Currie, P.J., Lee, Y.N. 2012. Tyrannosaur feeding traces on Deinocheirus (Theropoda: ?Ornithomimosauia) remains from the Nemegt Formation (Late Cretaceous), Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 37: 186 - 190.

Chinzorig, T., Kobayashi, Y., Tsogtbaatar, K., Currie, P.J., Takasaki, R., Tanaka, T., Iijima, M., Barsbold, R. 2017. Ornithomimosaurs from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia: manus morphological variation and diversity. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 91 - 100.

Claessens, L. P. A., and M. A. Loewen. 2016. A redescription of Ornithomimus velox Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(1):e1034593:1-15

Fanti, F., Bell, P.R., Tighe, M., Milan, L.A., Dinelli, E. 2017. Geochemical fingerprinting as a tool for repatriating poached dinoaur fossils in Mongolia: A case study for the Nemegt Locality, Gobi Desert. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 51 - 64.

Fowler DW, Woodward HN, Freedman EA, Larson PL, Horner JR (2011) Reanalysis of “Raptorex kriegsteini”: A Juvenile Tyrannosaurid Dinosaur from Mongolia. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21376.

Funston, G. F.; Mendonca, S. E.; Currie, P. J.; Barsbold, R. (2017). "Oviraptorosaur anatomy, diversity and ecology in the Nemegt Basin". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 - 82.

Holtz, T.R. 2014. Paleontology: Mystery of the horrible hands solved. Nature 515 (7526): 203 - 205.

Hurum, J. 2001. Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus. In Tanke, D. H., K. Carpenter, M. W. Skrepnick. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 34 - 41.

Jerzykiewicz, T., Russell, D.A. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Reserch 12 (4): 346 - 377.

Kobayashi, Y., Barsbold, R. 2006. Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea 22 (1): 195 - 207.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. 1969. Fossils from the Gobi desert. Science Journal 5(1):32-38

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 - 136.

Kundrat, M., Lee, Y.N. First insights into the bone microstructure of Deinocheirus mirificus. 13th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists: 25.

Lauters, P., Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Escuille, F.O., Godefroit, P. 2014. The brain of Deinocheirus mirificus, a gigantic ornithomimosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 166.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J. 2013. New specimens of Deinocherus mirificus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Abstracts of Papers: 161.

Lee, Y.N., Barsbold, R., Currie, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Lee, H.J., Godefroit, P., Escuillie, F.O., Chinzorig, T. 2014. Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. Nature 515 (7526): 257 - 260.

Madsen, E. K. 2007. Beak morphology in extant birds with implications on beak morphology in Ornithomimids. Dek Matematisk-Naturvitenskapelige Fakultet - Thesis. 1 - 21.

Makovicky, P.J., Kobayashi, Y., Currie, P.J. 2004. Ornithomimosauria. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H. eds. The Dinosauria. University of California Press.

McFeeters, B., M. J. Ryan, C. Schroder-Adams and T. M. Cullen. 2016. A new ornithomimid theropod from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36:e1221415:1-20

Middleton, K.M., Gatesy, S.M. 2000. Theropod forelimb design and evolution. Zoologicla Journal of the Linnean Society 128 (2): 160 - 172.

Mikhailov, K. E. 1991. Classification of fossil eggshells of amniotic vertebrates. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 36(2):193-238

Molnar, R.E. 2001. Theropod Paleopathology: a Literature Survey. In: Tanke, D.H., Carpenter, K. eds. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press.

Newbrey, M. G., Donald B. Brinkman, Dale A. Winkler, Elizabeth A. Freedman, Andrew G. Neuman, Denver W. Fowler and Holly N. Woodward (2013). "Teleost centrum and jaw elements from the Upper Cretaceous Nemegt Formation (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of Mongolia and a re-identification of the fish centrum found with the theropod Raptorex kreigsteini". In Gloria Arratia; Hans-Peter Schultze; Mark V. H. Wilson (eds.). Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 291–303.

Norell, M. A., P. J. Makovicky, P. J. Currie. 2001. The Beaks of Ostrich Dinosaurs. Nature 412 (6850): 873 - 874.

Norell, M.A.; Makovicky, P.J.; Bever, G.S.; Balanoff, A.M.; Clark, J.M.; Barsbold, R.; Rowe, T. (2009). "A Review of the Mongolian Cretaceous Dinosaur Saurornithoides (Troodontidae: Theropoda)". American Museum Novitates. 3654: 63.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Anchor. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Osmolska, H., Roniewicz, E. 1970. Deinocheiridae, a new family of theropod dinosaurs. Palaeontologica Polonica 21: 5 - 19.

Paul, G.S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster.

Paul, G.S. 2012. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press.

Roy, B., Ryan, M.J., Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B., Tsogtbaatar, K. 2018. Histological analysis of the gastralia of Deinocheirus mirificus from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. 6th Annual Meeting Canadian Society of Vertebate Paleontology.

Rozhdestvensky, A.K. 1970. Giant claws of enigmatic Mesozoic reptiles. Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal 1970 (1): 117 - 125.

Senter, P., Robins, J.H. 2012. Hip heights of the gigantic theropod dinosaurs Deinocheirus mirificus and Therizinosaurus cheloniformis, and implications for museum mounting and paleoeoclogy. Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History 14: 1 - 10.

Shuvalov, V.F. (2000). "The Cretaceous stratigraphy and palaeobiogeography of Mongolia". In Benton, Michael J.; Shishkin, Mikhail A.; Unwin, D.M.; Kurochkin, E.N. (eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–278.

Takanobu Tsuihiji, Brian Andres, Patrick M. O'connor, Mahito Watabe, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar & Buuvei Mainbayar (2017) Gigantic pterosaurian remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 - 18.

Watanabe, A., Eugenia Leone Gold, M., Brusatte, S.L., Benson, R.B.J., Choiniere, J., Davidson, A., Norell, M.A., Claessens, L. 2015. Vertebral pneumaticity in the ornithomimosaur Archaeornithomimus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) revealed by computed tomography imaging and reappraisal of axial pneumaticity in ornithomimosuria. PLoS ONE 10 (12): e0145168.

Zelenitsky, D K., F. Therrien, G. M. Erickson, C. L. DeBuhr, Y. Kobayashi, D. A. Eberth, F. Hadfield. 2012. Feathered non-avian dinosaurs from North America provide insight into wing origins. Science 338 (6106): 510 - 514.

#Deinocheirus mirificus#Deinocheirus#Ornithomimosaur#Dinosaur#Duck Satan#Dinosaurs#Feathered Dinosaurs#Feathered Dinosaur#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Mesozoic Monday#Cretaceous#Herbivore#Eurasia#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some more drawings of my wheagle beastie. Sketches of the head and skull from different angles, and studies of the tail/pygostyle anatomy. Someday I’d like to do a full dorsal reference of the animal (in addition to many other studies and illustrations!) but this tail ref will have to do for right now.

#creature design#bird creature#creature anatomy#creature skull#tail anatomy#bird anatomy#skull#concept art#musculature#tail muscles#beaked whale#ziphiidae#tail feathers#anatomy#muscle anatomy#labeled anatomy#anatomical drawing

12 notes

·

View notes