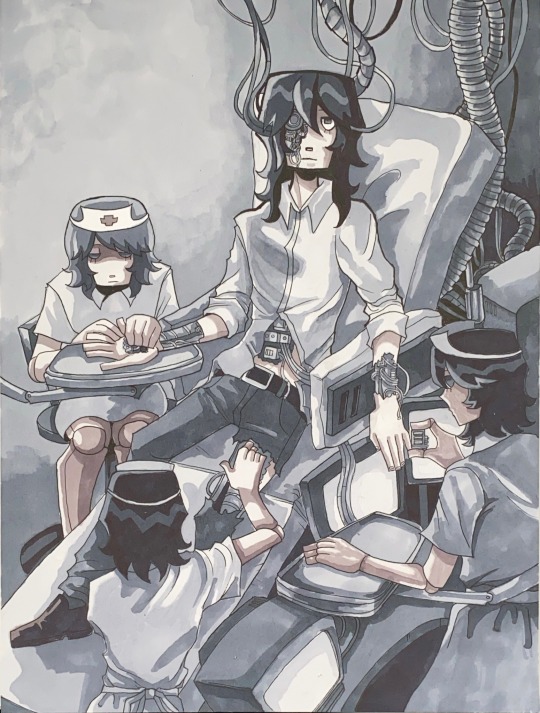

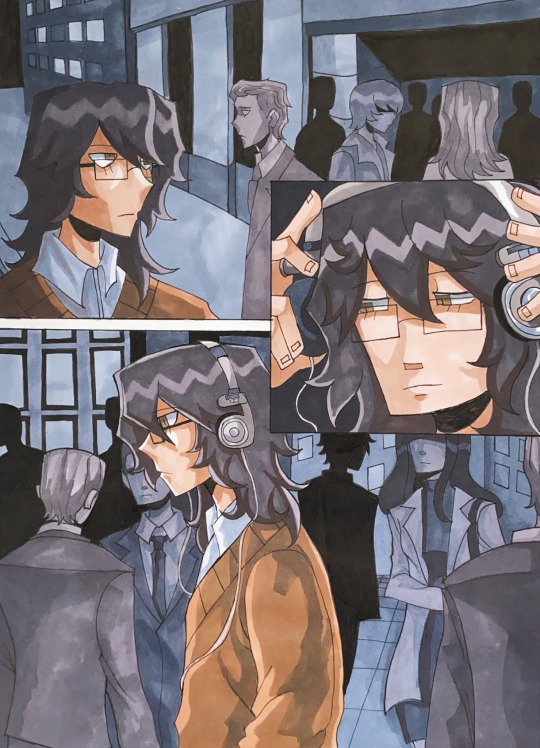

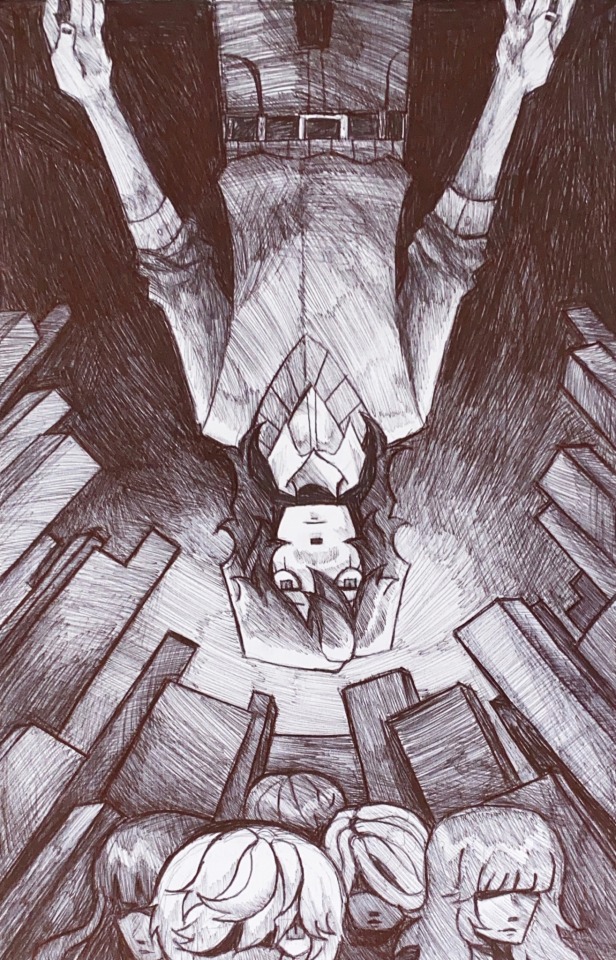

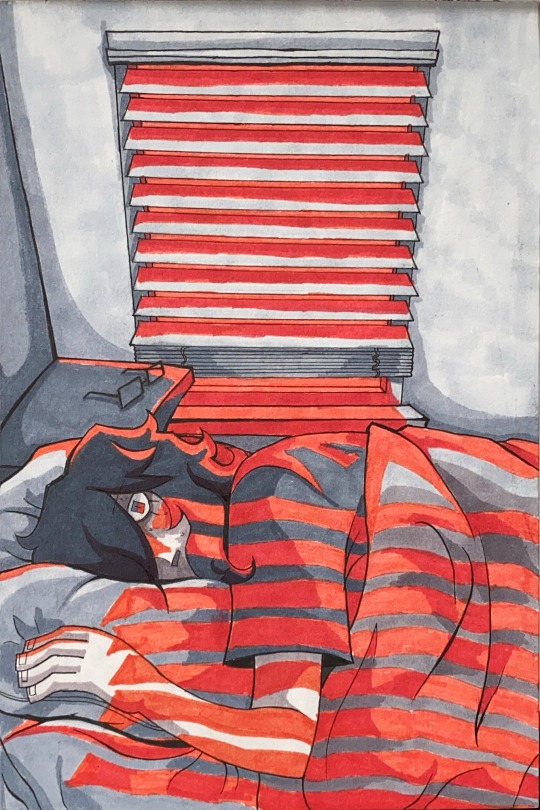

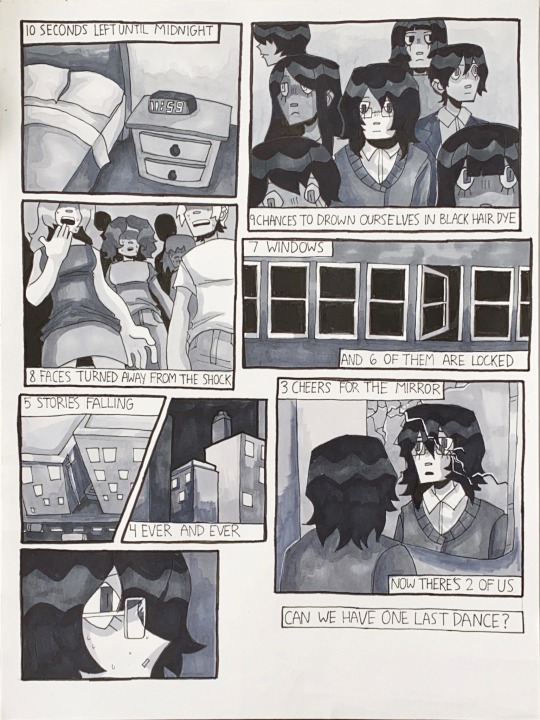

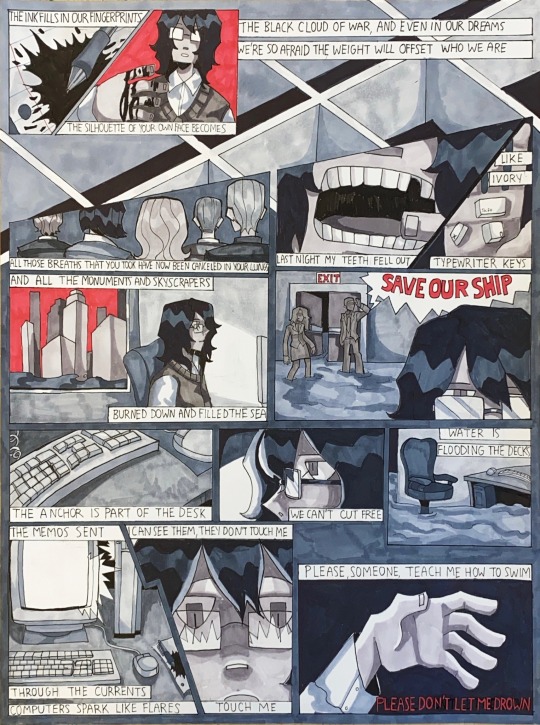

#poured my entire balls and soul into this ! manifest a 5

Text

ap portfolio

#my theme was the album war all the time by thursday#art#artist#artists on tumblr#drawing#portfolio#ap portfolio#ap drawing#ap art#ap art portfolio#poured my entire balls and soul into this ! manifest a 5

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death, Disbelief and Doctorates

That secular modernity has not come to South Asia has been a source of embarrassment for Western academics and our local intelligentsia, influenced by the former. This should not have come as a surprise if we consider the literature of the region in modern times, especially in its treatment of death. Death is not a problem in South Asia, as it became a problem in Western society. Consider Shakespeare’s reassuring view of death:

Men must endure

Their going hence, even as their coming hither;

Ripeness is all.

And Edmund Spenser happily urged:

Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song.

The poetry produced had a cheerful aspect, which is not to say that dark themes were not discussed. Thus, Hamlet reflects on death, and its afterwards:

To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause

Here, we see every man and woman’s anxiety regarding the posthumous life, if any.

With the Romantics, things appear darker: Death is now a problem. “It is at these extremes of human nature which they know so well how to explore, where horror and delight, love and hate, cruelty and tenderness are indistinguishable, that the Romantics sought a heightened, transformed, superhuman existence which might abolish life as it is actually lived; nationalism is the political expression of this quest....Nationalism looks inwardly, away from and beyond the imperfect world. And this contempt of things as they are, of the world as it is, ultimately becomes a rejection of life, and a love of death (Elie Kedourie, Nationalism (London: Hutchinson & Co Ltd, 1969), p 87).”

But I would add that the loss of religious faith beginning to be felt led to a meaninglessness regarding death, and nationalism as a new secular religion would eventually command men’s allegiance as religion had done.

As Benedict Andersen observes: “...in Western Europe the eighteenth century marks not only the dawn of the age of nationalism but the dusk of religious modes of thought. The century of the Enlightenment, of rationalist secularism, brought with it its own modern darkness. With an ebbing of religious belief, the suffering which belief in part composed did not disappear. Disintegration of paradise: nothing makes fatality more arbitrary. Absurdity of salvation: nothing makes another style of continuity necessary. What then was required was a secular transformation of fatality into continuity, contingency into meaning. As we shall see, few things were (are) better suited to this end than an idea of nation (Imagined Communities, Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006) pp 10-11.)” The great religions provide the existential answers to immemorial questions: “Why was I born blind? Why is my best friend paralysed? Why is my daughter retarded?”

In addition, language confers a sort of vicarious immortality - the syllables survive as soul. As Andersen quotes: “Yes, it is quite accidental that I am born French; but after all, France is eternal (p 12).”

Peter Berger put his finger on it when he wrote that religion - the “sacred canopy” - protects the believer, and his or her community, from the possibility that life has neither meaning nor purpose (Grace Davie, The Sociology of Religion (New Delhi, SAGE: 2008), p 53). “What happens to us when we die?”, according to Davie (p 19), has become a pivotal social and sociological question today.

How wonderful is Death,

Death and his brother Sleep!

Thus begins Shelley’s utopian poem, Queen Mab. But he went on to be more personal than that: in Stanzas Written in Dejection near Naples, he contemplates his death as a release from despair. Like a tired child, he would lie down and weep away a life of care

Till death like sleep might steal on me,

And I might feel in the warm air

My cheek grow cold, and hear the sea

Breathe o'er my dying brain its last monotony.

The atheist, evicted from Oxford for his polemic The Necessity of Atheism, still yearned for immortality which he found in scenes of desolation:

I love all waste

And solitary places; where we taste

The pleasure of believing what we see

Is boundless, as we wish our souls to be

Byron’s perfervid regret at being alive echoes even today with lyrical pathos:

Count o’er the joys thine hours have seen,

Count o’er thy days from anguish free,

And know, whatever thou hast been,

’Tis something better not to be.

And every schoolchild knows Keats’s famous death-wish:

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a musèd rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

These dark themes fructify, if that’s the word, into “the beginning of the coming universal wish not to live”, as the advanced doctor informs Jude in the novel by Thomas Hardy, inspired, again, if that’s the word, by the dour philosophy of Schopenhauer.

Modern Bengali literature dates, somewhat inauspiciously, from the founding of Fort William College in 1800. Education was soon to be Anglicised - and occidentalised. Lord William Bentinck put an end to the employment of the vernacular. From 1830, public instruction was to be in English.

The era of Rabindranath Tagore (1890-1930) witnessed the poet’s prolific output. Translations can ill convey the lyrical beauty of his poetry. He was heavily influenced by the Romantics, not only in the form of his poetry, but also in his love of nature. However, he - and his successors - showed little preoccupation with life’s absurdity and hardly shared the former’s obsession with death. Death is not a problem in South Asia. Indeed, it seems difficult for the South Asian mind to think beyond religion. The other function of religion - to promote social bonding, as Davie observes (p 19) - seems eminently fulfilled in these parts: the group encapsulates one throughout one’s entire lifetime. A poet may die so young, as Auden put it, but here he or she will scarcely ever live for years alone. Although the Hofstede individualism index must be treated with caution, a low score for Bangladesh rather adequately describes the “embeddedness” of the individual in society. “Bangladesh, with a score of 20 is considered a collectivistic society. This is manifest in a close long-term commitment to the member ‘group’, be that a family, extended family, or extended relationships. Loyalty in a collectivist culture is paramount, and over-rides most other societal rules and regulations. The society fosters strong relationships where everyone takes responsibility for fellow members of their group.”

The expectation that religion will, or should disappear, is a Western expectation. And when it doesn’t, the outcome is considered illegitimate. That would not have mattered had the disappointment been restricted to Western scholars and academics. Our academics, heavily influenced, share the expectation, turning the universities into citadels of alienation (as Hugh Tinker observed with regard to communism). The international “faculty club” observed by Peter Berger, the globalisation of academia, shares a subculture of animosity towards religion, just as it shared animosity towards capitalism at one time during the Cold War. Scholars bring back more than PhDs from the London School of Economics.

“If Europe is not the global prototype,” intones Grace Davie in defence of her book, “both Europe and European scholars have everything to learn from cases other than their own. Not least among such lessons is the importance of taking the religious factor seriously, and in public as well as private life. Taking religion seriously, moreover, is greatly facilitated by the assumption that you expect it to be there, as an integral, normal part of modern as well as modernising societies. That is the assumption embedded in the argument of this book (p 109).”

The 2001 British Census threw up a surprise. Those with “no religion” did not happen to be clustered in the large conurbations of the industrial North of Britain, but in “a markedly different group of cities in the South, very often those where a university and its employees form a sizeable section of the population (p 92).”

Analytic thinking predisposes people to religious scepticism, argues Ara Norenzayan. As an example, he picks a puzzle from Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

The intuitive answer - 10 cents - is wrong. The correct answer is 5 cents. “Participants who were more likely to overrule the intuitive answer were also less likely to believe in God (Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), p 182).” Slow thinking, rather than fast thinking yields greater caution in belief.

“What about entire subcultures where analytic thinking is the gold standard, inculcated every day? These subcultures are called universities. And indeed, this link between analytic thought and disbelief might explain the overrepresentation of disbelievers among the more educated classes (p 185).”

He ought to have added, “In WEIRD societies.” [= White, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic] For this doesn’t appear to happen here. For evidence that socialisation rather than analytic thinking makes us cautious in belief-claims, look no further than the hatriots churned out of universities in Bangladesh. These people are in a cultural fix: with their Western drinking-buddies, they must don an analytic hat; with their local confreres, they must doff the cap. For our university graduates have more in common with high school dropouts in Paris than with the Sorbonne graduates: they are as nationalist as the National Rally voters and not at all likely, in private, to receive with approbation Emmanuel Macron’s elitist barb: the leprosy of nationalism.

He echoes and amplifies the words of Norman Davies regarding Europe before the Great War: “The educated, multilingual cosmopolitan elite of Europe grew weaker, the half-educated national masses, who thought of themselves only as Frenchmen, Germans, English or Russians, grew stronger.”

Collective life will always trump individual rationality in Bangladesh, and, indeed, South Asia.

1 note

·

View note