#podlachia

Text

Podlachia, Poland by agsobczak

#podlasie#poland#europe#podlachia#travel#wanderlust#storks#stork#nature#nature photography#naturecore#travelblr#travelblogpost#travelgram#cottagecore#countrycore#rural landscape#slavic#meadowcore#birds

644 notes

·

View notes

Text

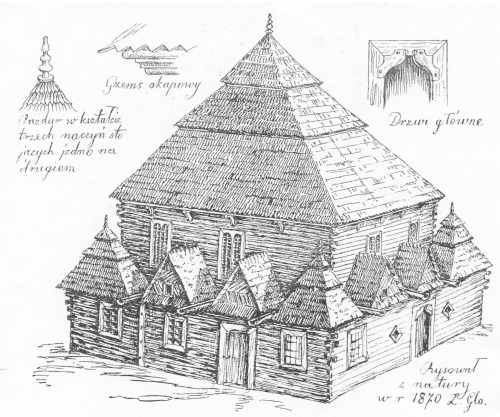

Wooden synagogue of Wysokie Mazowieckie, eastern Poland, drawing from 1870

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish "Purimshpiler" musicians in military uniform, Knyszyn, Poland, 1897

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Branicki family guest palace in Białystok – Pałacyk gościnny Branickich w Białymstoku

The building is situated in the city centre, near the palace and garden complex of the Branicki family, north of the grand courtyard; today, the edifice forms the eastern terminating vista of the representational avenue known as Kilińskiego street. The palace was designed in the Baroque style, its interiors exhibiting a strong Rococo influence.

#Branicki family guest palace#Pałacyk gościnny Branickich#Pałac Branickich#Branicki Palace#Palais Branicki#Branicki-Palast#Дворец Браницких#Białystok#Podlasie#Podlachia#Balstogė#Беласток#Білосток#ביאַליסטאָק#Белосток#Bjelostock#Bialystok#castle#palace#château#Schloss#замок#Jan Klemens Branicki#Versailles de la Pologne#Versailles de la Podlachie#Versailles of Podlasie#Versailles of Poland#Polska#Polen#Podlachien

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DZIADY

(literally "grandfathers, eldfathers" // sometimes translated as Forefathers' Eve)

• Belarusian — Dzyady

• Russian — Dedy

• Ukrainian — Didy

• Polish — Dziady

👻 A term in Slavic folklore for the spirits of the ancestors and a collection of pre-Christian rites, rituals and customs that were dedicated to them. The essence of these rituals was the "communion of the living with the dead", namely, the establishment of relationships with the souls of the ancestors, periodically returning to their headquarters from the times of their lives. The aim of the ritual activities was to win the favor of the deceased, who were considered to be caretakers in the sphere of fertility. The name "dziady" was used in particular dialects mainly in Poland, Belarus, Polesie, Russia and Ukraine (sometimes also in border areas, e.g. Podlachia, Smoleńsk Oblast, Aukštaitija), but under different other names (pomynky, przewody, radonitsa, zaduszki) there were very similar ritual practices, common among Slavs and Balts, and also in many European and even non-European cultures.

👻 Within the framework of grandfather's rituals, the souls coming to "this world" had to be hosted in order to secure their favour and at the same time help them to achieve peace in the hereafter. The basic ritual form was feeding and watering of souls (e.g. honey, groats, eggs, forge and vodka) during special feasts prepared in houses or cemeteries (directly on graves). A characteristic feature of these feasts was that the people who ate them dropped or poured some of their food and drinks on the table, floor or grave for the souls of the deceased. In some areas, however, the ancestors also had to be given the opportunity to bathe (a sauna was prepared for this) and warm up.This last condition was fulfilled by lighting fires, whose function is sometimes explained differently. They were supposed to light the way for wandering souls so that they would not get lost and could spend the night with their loved ones.

👻 In the Slavic tradition, depending on the region, the feast of the deceased was celebrated at least twice a year. The main dziady were the so-called spring dziady and autumn dziady:

• Spring dziady were celebrated around 1 and 2 May (depending on lunar phase).

• Autumn dziady were celebrated on the night from October 31 to November 1, also known as All Souls' Day, which was a preparation for the autumn day of the dead, celebrated around November 2.(depending on lunar phase).

👻 To this day, in some regions of eastern Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and part of Russia, it is cultivated to carry on the graves of the dead a symbolic meal in clay pots. The majority of Slavic neo-pagan and rodnover movements also cultivate the dziady.

👻 Christianity, on the one hand, fought against pagan rituals, successively banning them, and on the other hand, it tried to adapt some of them in an attempt to christianize them. In the case of the dziady, both the Catholic and the Orthodox Church tried to marginalize and then eliminate pagan festivals by introducing into their squares (at the same or similar moments of the annual cycle) Christian festivals and practices). In Poland it's All Saint's Day at November 1, which is celebrated by most Polish people instead of dziady.

#some ppl were interested in *slavic halloweeen*#Dziady#Halloween#slavic culture#slavic#slavs#pagan#slavic folklore#polish folklore#russian folklore#ukrainian folklore#poland#russia#belarus#ukraine#posted by me#🔮

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kartacze - Polish Meat-filled Potato Dumplings (Podlachia Region) (recipe in Polish)

#kartacze#cepeliny#poland#dinner#polish food#meat-filled potato dumplings#traditional food#traditional dumplings#dumplings#dinner inspiration#dinner ideas#potato dumplings#foodblr#polish cuisine#meat#food#regional food#podlasie#suwałki#comfort food

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unfinished stuff i was drawing while visiting grandparents in Podlachia (east region of Poland)

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#traveling#poland#cottage#explore#vintage#rustical#boho#home#house#nature#forest#podlachia#supraśl#hippie#nomand

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podlachia, Poland by jordan.plis

#podlasie#podlachia#poland#central europe#nature#slavic#countryside#rural landscape#rustic#rustic aesthetic#travel#europe#countrycore#cottage#cottagelife#cottagecore#slow living#polishcore#the witcher#farmcore

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

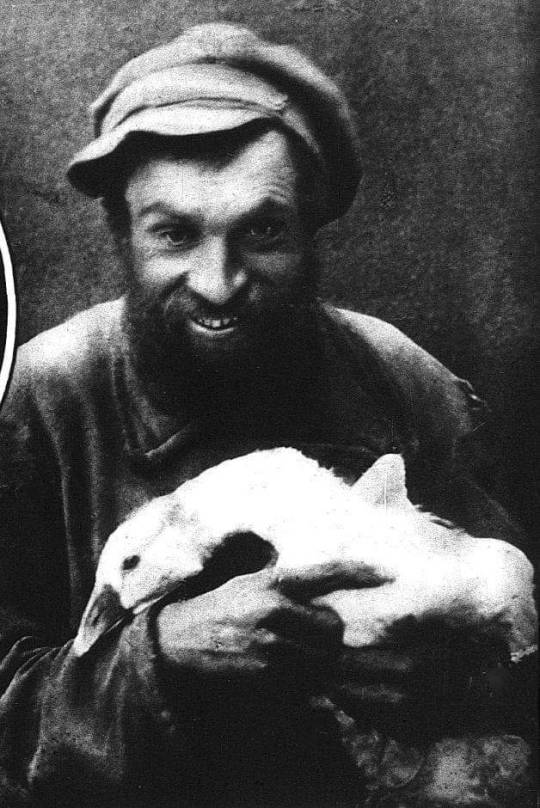

Jew with a goose in Sokółka County, northeastern Poland

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Branicki Palace (Polish: Pałac Branickich) is a historical edifice in Białystok, Poland. It was developed on the site of an earlier building in the first half of the 18th century by Jan Klemens Branicki, a wealthy Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth hetman, into a residence suitable for a man whose ambition was to become king of Poland. The palace complex with gardens, pavilions, sculptures, outbuildings and other structures and the city with churches, city hall and monastery, all built almost at the same time according to French models was the reason why the city was known in the 18th century as Versailles de la Pologne (Versailles of Poland) and subsequently Versailles de la Podlachie (Versailles of Podlasie).

#Pałac Branickich#Branicki Palace#Palais Branicki#Branicki-Palast#Дворец Браницких#Białystok#Podlasie#Podlachia#Balstogė#Беласток#Білосток#ביאַליסטאָק#Белосток#Bjelostock#Bialystok#castle#palace#château#Schloss#замок#Jan Klemens Branicki#Versailles de la Pologne#Versailles de la Podlachie#Versailles of Podlasie#Versailles of Poland#Polska#Polen#Podlachien#Wersal Podlasia#Wersal Północy

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fuori media e ong, ma c’è una Polonia di confine che aiuta Chi in Polonia vuole raccontare la crisi migratoria al confine non si può sentire al sicuro neanche fuori dalla zona d’emergenza. Nel pomeriggio di martedì l’esercito polacco ha aggredito tre fotogiornalisti nei dintorni del villaggio di Michalowo, una località vicina ma non all’interno della cosiddetta no entry zone di 3 chilometri, alla frontiera con la Bielorussia. La notizia è stata data dalla Press Club Polska (Pcp), un’associazione polacca della stampa. In un comunicato rilasciato qualche ora dopo, il ministero della Difesa della Polonia ha negato che sia stata usata violenza nei loro confronti ma i lividi sui polsi di due dei fotoreporter, nelle immagini pubblicate da Pcp, non lasciano adito a dubbi. IN QUESTO MOMENTO a poter raccontare meglio il conflitto non sono le ong o la stampa, tenuti lontani dall’epicentro della crisi, ma i cittadini che vivono nella zone al confine. Lo hanno fatto ieri con una lettera-appello alle istituzioni polacche gli «abitanti dell’area della Foresta di Bialowieza», residenti nella regione della Podlachia, nel profondo nordest del paese. (...) «Comprendiamo le numerose restrizioni e limitazioni con le quali, vivendo nella zona di stato di emergenza, dobbiamo confrontarci», si legge nella missiva firmata da oltre un centinaio di persone che vivono intorno a una delle ultime foreste primarie in Europa. (...) Ecco cosa scrivono nell’appello indirizzato al presidente Andrzej Duda e al premier Mateusz Morawiecki, ricco di testimonianza dirette: «Non lontano dalle nostre case, tra i canneti lungo il fiume, un padre di tre figli sta cercando di proteggerli dalle gelate notturne. Uno dei bambini, un maschietto di tre anni, è malato, ha problemi di stomaco, presumibilmente per aver bevuto acqua sporca, non ha pannolini né vestiti di ricambio. Tutti e quattro trascorrono la notte in vestiti sporchi e bagnati». GLI AUTORI DELLA LETTERA non dimenticano le responsabilità del regime di Lukashenko in merito alla crisi. «Questo è un atto disumano: dal momento che non ci sono dubbi che il regime bielorusso è crudele con i rifugiati, perché allora le forze dell’ordine polacche – per usare una metafora che ogni polacco dovrebbe intendere – scortano questi profughi fin sotto ai cancelli del “lager”?». Infine, i firmatari della lettera invocano con urgenza un cambiamento di rotta da parte del governo: «Lo spirito umanitario di noi abitanti della zona di emergenza è messo alla prova con durezza perché, a causa dell’impossibilità di accedere ai servizi preposti all’assistenza e alla sicurezza, dobbiamo agire di nostra iniziativa. Con l’inverno imminente, prevediamo che la situazione diventerà drammatica». INTANTO IL VALICO di Kuznica è chiuso da una settimana e anche il commercio si è fermato. I bielorussi non possono più andare oltreconfine a rivendere benzina a prezzi ribassati ai polacchi e nemmeno comprare generi alimentari di qualità migliore dai propri vicini. A essere colpiti anche il segmento turistico e quello della ristorazione. Lunedì sono arrivati i primi risarcimenti per gli imprenditori delle zone del voivodato di Lublino in cui vige lo stato di emergenza. Ma la situazione resta difficile per molti. Si tratta di una piccola crisi, in quella ben più grande e drammatica, che stanno vivendo le persone finite nel limbo infernale tra Polonia e Bielorussia. Giuseppe Sedia

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

#rogowo #poland #europe #weekend #family #podlachia #podlasie #dji #spark #saab #saab95ng (at Rogowo, Bialystok, Poland)

0 notes

Text

Denunce da Bialystok: "Da gennaio sempre più rischi e arresti"

Denunce da Bialystok: “Da gennaio sempre più rischi e arresti”

“Chi aiuta le persone al confine ucraino è trattato come un eroe. In tv vediamo militari e guardie di frontiera dare una mano, prendere in braccio i bambini ucraini, ma la situazione cambia drasticamente quando si tratta di aiutare i migranti al confine con la Bielorussia. L’intera regione di Podlachia sta subendo enormi pressioni: i militari sono ovunque, fermano la gente e controllano le auto,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Open main menu

Search

Third Partition of Poland

Language

Download PDF

Watch

Edit

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg Monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Polish–Lithuanian national sovereignty until 1918. The partition was the result of the Kościuszko Uprising and was followed by a number of Polish uprisings during the period.[1]

Third Partition of Poland

Aftermath of the Third Partition of the Commonwealth, with the disappearance of sovereign Poland and Lithuania.

Population losses in the 3rd PartitionTo Austria1.2 millionTo Prussia1 millionTo Russia1.2 millionFinal territorial lossesTo PrussiaNorthern and Western Poland (Podlachia)To the Habsburg MonarchySouthern Poland (Western Galicia and Southern Masovia)To RussiaLithuania

BackgroundEdit

Further information: Partitions of Poland, Polish–Russian War of 1792, and Kościuszko Uprising

Learn more

This section does not cite any sources.

Following the First Partition of Poland in 1772, in an attempt to strengthen the significantly weakened Commonwealth, King Stanisław August Poniatowski put into effect a series of reforms to enhance Poland's military, political system, economy, and society. These reforms reached their climax with the enactment of the May Constitution in 1791, which established a constitutional monarchy with separation into three branches of government, strengthened the bourgeoisie and abolished many of the nobility's privileges as well as many of the old laws of serfdom. In addition, to strengthen Poland's international standings, King Stanislaus signed the Polish-Prussian Pact of 1790, ceding further territories to Prussia in exchange for a military alliance. Angered by what was seen as dangerous, Jacobin-style reforms, Russia invaded Poland in 1792, beginning the War in Defense of the Constitution. Abandoned by her Prussian allies and betrayed by Polish nobles who desired to restore the privileges they had lost under the May Constitution, Poland was forced to sign the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, which ceded Dobrzyn, Kujavia, and a large portion of Greater Poland to Prussia and all of Poland's eastern provinces from Moldavia to Livonia to Russia, reducing Poland to one-third of her original size before the First Partition.[citation needed]

Outraged with the further humiliation of Poland by her neighbors and the betrayal by the Polish nobility, and emboldened by the French Revolution unfolding in France, the Polish masses quickly turned against the occupying forces of Prussia and Russia. Following a series of nationwide riots, on 24 March 1794, Polish patriot Tadeusz Kościuszko took command of the Polish armed forces and declared a nationwide uprising against Poland's foreign occupiers, marking the beginning of the Kościuszko Uprising. Catherine II and Frederick William II were quick to respond and, despite initial successes by Kosciuszko's forces, the uprising was crushed by November 1794. According to legend, when Kosciuszko fell off of his horse at the Battle of Maciejowice, shortly before he was captured, he said "Finis Poloniae", meaning in Latin "[This is] the end of Poland."[citation needed]

TermsEditLearn more

This section does not cite any sources.

Austrian, Prussian, and Russian representatives met on 24 October 1795 to dissolve the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, with the three conquering powers signing a treaty to divide the region on 26 January 1797. This gave the Habsburg Monarchy control of the Western Galicia and Southern Masovia territories, with approximately 1.2 million people; Prussia received Podlachia, the remainder of Masovia, and Warsaw, with 1 million people; and Russia received the remaining land, including Vilnius and 1.2 million people. Unlike previous partitions, no Polish representative was party to the treaty. The Habsburgs, Russia, and Prussia forced King Stanislaus to abdicate and retire to St. Petersburg, where he died as Catherine II's trophy prisoner in 1798. The victors also agreed to erase the country's name:

"In view of the necessity to abolish everything which could revive the memory of the existence of the Kingdom of Poland, now that the annulment of this body politic has been effected ... the high contracting parties are agreed and undertake never to include in their titles ... the name or designation of the Kingdom of Poland, which shall remain suppressed as from the present and forever ..."[2][page needed]

Aftermath

See also

References

External links

Last edited 2 months ago by Tom.Reding

RELATED ARTICLES

Partitions of Poland

Three late-18th-century forced partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

West Galicia

Polish–Prussian alliance

Content is available under CC BY-SA 3.0 unless otherwise noted.

Privacy policy

Terms of Use

Desktop

thanks for sending things about (fictional) poland

0 notes