#picture play magazine

Text

Picture Play Magazine (1937)

#katharine hepburn#picture play#picture play magazine#old magazines#vintage#vintage magazine#old hollywood#old movies#old films#screwball comedy#1930s#1937

497 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture Play Magazine, January 1932.

#anna may wong#1930s#picture play magazine#old hollywood#old movies#old magazines#old movie stars#classic hollywood#old hollywood glamour#old hollywood actress#vintage style#vintage fashion#old hollywood actors#1930s movies#30s#1930s style#classic movie stars#30s movies

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

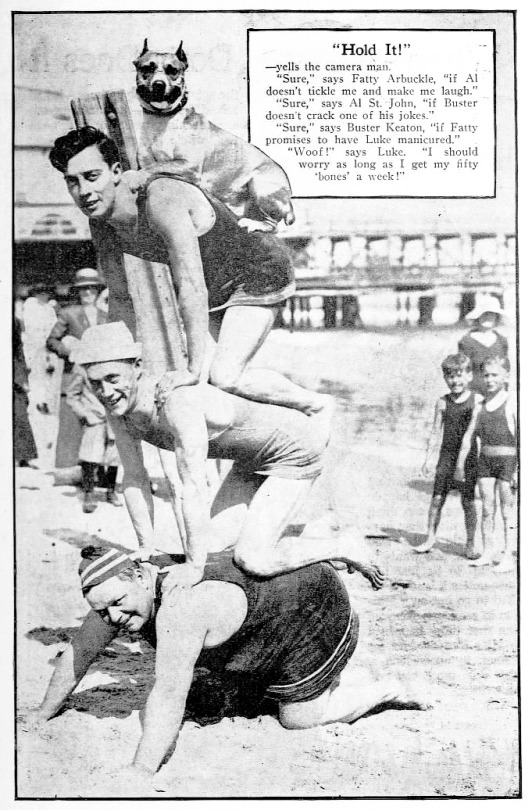

Luke, Buster Keaton, Al St. John & Roscoe Arbuckle in Picture Play Magazine - 1918

#buster keaton#luke the dog#al st john#roscoe arbuckle#1918#1910s#picture play magazine#silent film#silent comedy#silent cinema#silent era#film#comedy#cinema#movies#pre code#pre code hollywood#pre code film#pre code era#damfino#damfinos#black and white#1920s#vintage hollywood#buster edit#old hollywood#slapstick

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

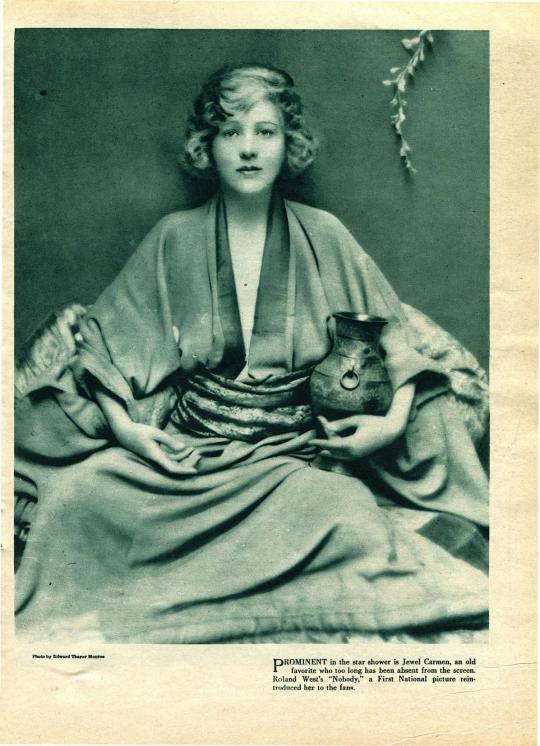

Mary Thurman by Hoover Art Co.

"Mary Thurman can be temperamental and indulge in Oriental garb if she likes─ emerging from the realm of bathing beauties to featured roles in Dawn productions is sufficient excuse." (caption)

Picture Play magazine, June 1920 | src internat archive

#hoover art co.#hoover#hoover art co#portrait#1920s#round view#mary thurman#head wrap#pictorial portrait#Bildnis#Aufnahme#oriental costume#Picture Play#Picture Play magazine#old magazines#old hollywood

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lillian Gish photographed by Abbe as seen in the October 1923 issue of Picture Play Magazine

Caption: This glimpse of one of the early scenes in "The White Sister," Lillian Gish's first picture for the Inspiration company, holds rare promise of beauty, for it seems to have caught in its very backgrounds her ephemeral charm.

#lillian gish#1920s#1923#Picture Play Magazine#movie magazine#film magazine#The White Sister#silent era#silent movies#silent film#classic movies#classic film

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

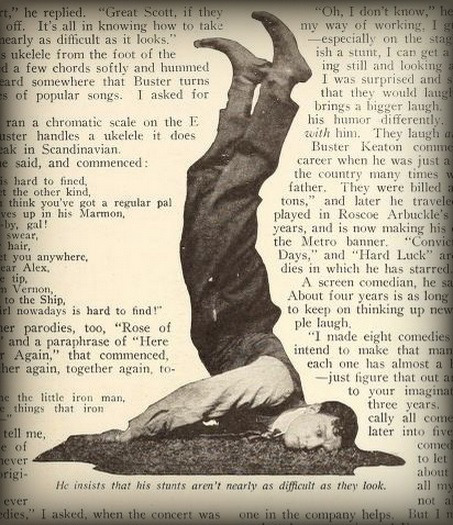

Picture-Play Magazine, July 1921. By Emma-Lindsay Squier

HE REALLY CAN SMILE

And strangely enough it was in the hospital that “Buster” Keaton first proved it. There’s a good reason for his smiling, and her name is Natalie Talmadge, soon to be Natalie Keaton.

“Well, Mr. Keaton,” I said kindly, “I’m sorry to have to interview you here.”

“Well, Miss Squier,” said Mr. Keaton just as kindly, “I’m sorry to have you.”

That made it unanimous. I, the interviewer, was standing at the foot of a bed. Buster Keaton, the interviewee, was in the bed. The bed was in a hospital. So was Buster.

All around the white walls of the perfectly antiseptic room various sign cards were posted, all typically Keatonesque. Having one’s ligaments wrenched out of place doesn’t deaden one’s sense of humor–if one happens to be a screen comedian.

“Standing Room Only.” One of them read. Other masterpieces were: “We Close Saturdays at One O’Clock.” “No Shooting Allowed on These Premises. “Not Responsible For lost Valuables.” “Furnished Room For Rent.”

One effusion was hand printed, and was the result of Buster’s bump of poetry–which, however, is not the bump that put him in the hospital.

“Hi diddle diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon.

If an old cow can do it

I thought I’d improve it–

I’ll be out of the hospital soon!”

Strangely enough, Buster Keaton was smiling. And that’s more than you’ve seen Buster do, even if you’ve watched him through his sixteen years on the stage, and his subsequent three or four years on the screen. They call him the “melancholy comedian” in pictures, because his sadness never lifts. Kicked or kissed, it is all the same to him. His expression of gentle gloom doesn’t change. They tell me that when he was in the army no one ever saw him smile–but then, the army is no laughing matter at best.

As I said before, he was smiling, though his leg was in a cast, and his face was a trifle wan. His sense of humor seems to be always on the alert. His mother sat besides the bed. She was smiling, too. The joke was a page from a Muskegon, Michigan, paper. It contained an ad for one of Buster’s comedies, and it read “Muskegon’s Own! Buster Keaton! His latest picture to-night, straight from the Capitol Theater, New York!”

“‘Muskegon’s Own!'” repeated Buster. “Sounds like a bottle of catsup.”

“Where you born there?” I asked.

Buster and his mother grinned at each other. She looks young enough to be his sister, and you can see that they are great pals.

“No, but I lived there between seasons on the road and went to school–oh it’s the old home town, all right–I get an awful kick out of that ad. When I come back from the East after getting married, I’m going to stop off and see all the gang. Maybe get up a little impromptu act for one of the theaters.

“The reason I smiled when you asked about my birthplace,” he went on, “was because the place where I was born isn’t there any more. It was in Kansas, and shortly after I arrived, there was a cyclone that demolished the place. They never did build it up.”

We talked some more about the prospect of returning to Muskegon.

“I will probably have the same experience that Will Rogers did,” he said. “He went back to his home town–somewhere in Wyoming I think it was–and met one of his old cow-puncher friends on the street.

“‘Is that you, Will Rogers?’ the old friend said. Will owned up that it was.

“‘Well,’ said the other wonderingly, ‘where have you been all these years?'”

I asked Buster when he and Natalie Talmadge were going to be married.

“I don’t just exactly know,” he smiled, showing a long dimple in his cheek that you’d never guess was there. “That’s up to my better nine-tenths–meaning Natalie–and, of course, the condition of my leg has something to do with it. I’ve been in bed now for five weeks, and the doctors think that I’m in for three more. Then I’ll have to dash around on crutches for a while–and after that–New York!”

He sighed ecstatically. What he really meant, was, “Natalie!”

I was curious to know the details of his accident–the first one he has ever had–but he was reticent. On a revolving stairway the mechanism had gone wrong, he leg was caught–that was all. His mother regarded him with pride.

“He has never hurt himself in a fall–and he has been doing acrobatic tumbling ever since he was a small child.”

I wanted to know if the falls he takes weren’t rather painful.

“They don’t hurt,” he replied. “Great Scott, if they did, they’d kill me off. It’s all in knowing how to take the fall. It isn’t nearly as difficult as it looks.”

He picked up his ukelele from the foot of the bed. He strummed a few chords softly and hummed a tune. I had heard somewhere that Buster turns out clever parodies of popular songs. I asked for one.

He smiled, a ran a chromatic scale on the E string. When Buster handles a ukelele it does everything but speak in Scandinavian.

“Here’s one,” he said, and commenced:

“A good girl is hard to fined,

You always get the other kind,

Just when you think you’ve got a regular pal

Lew Cody drives up in his Marmon,

And it’s good-by, gal!

And then you swear,

You tear your hair,

But it don’t get you anywhere,

So don’t go near Alex,

Take this little tip,

Stay away from Vernon,

Don’t take her to the Ship,

For a good girl nowadays is hard to find!”

There were other parodies, too, “Rose of Universal Square,” and a paraphrase of “Here We Are Together Again,” that commenced, “Here I am, together again, together again, together again,

They have called me the little iron man,

But there are some things that iron won’t stand–“

On the set, they tell me, Buster is the “life of the party.” He is never at a loss for an original song.

“Why don’t you ever smile in your comedies,” I asked, when the concert was over.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he answered, “it’s just my way of working, I guess. I have found–especially on the stage–that when I finish a stunt, I can get a laugh just by standing still and looking at the audience as if I was surprised and slightly hurt to think that they would laugh at me. It always brings a bigger laugh. Fatty Arbuckle gets his humor differently. The people laugh with him. They laugh at me.”

Buster Keaton commenced his theatrical career when he was just a toddler. He toured the county many times with his mother and father. They were billed as “The Three Keatons,” and later he travelled by himself. He played in Roscoe Arbuckle’s company for three years, and is now making his own comedies under the Metro banner. “Convict No. 13,” “Seven Days,” and “Hard Luck” are some of the comedies in which he has starred.

A screen comedian, he says, has little future. About four years is as long as any one can hope to keep on thinking up new ideas to make people laugh.

“I made eight comedies in the last year. I intend to make that many next year. And each one has almost a hundred ‘gags’ in it–just figure that out and see what happens to your imagination at the end of three years. That’s why practically all comedians go sooner or later into five-reel stories with a comedy angle. It’s easier to let some one else worry about the laughs. I string all my stuff together–no, not alone, because every one in the company helps. But I mean that I’ve never yet bought a scenario, and I’ve had thousands of them offered me. I can’t find funny scenarios. If I could, I’d play a wonderful price for them.”

The nurse “ahemed!” politely. I took it that the visiting hour was over.

“Come and see me at the studio in New York,” he invited. “Or, better still, stop off in Muskegon, Michigan, on your way East. The folks there are mighty nice to strangers and–”

But I don’t think I will. If Buster was there, what chance would I have? None, with “Muskegon’s Own” taking up all the attention.

Picture-Play Magazine, July 1921.

#buster keaton#picture play magazine#silent movies#comedy#1920s#silent film#silent comedy#1920s cinema

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

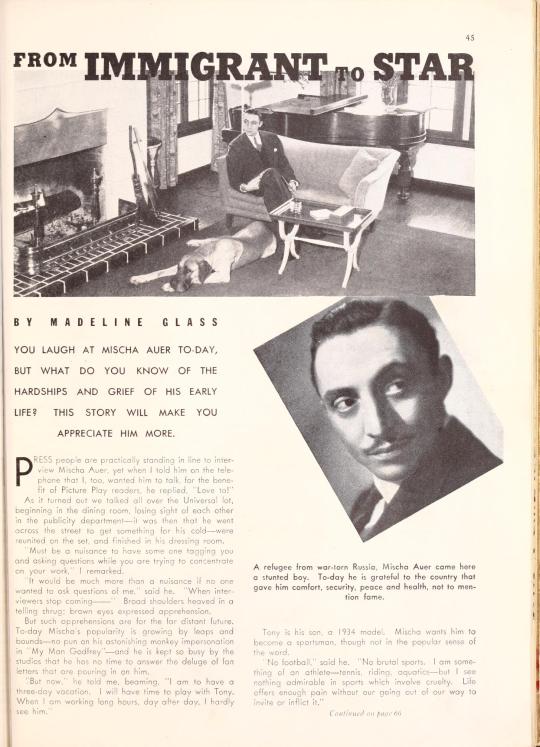

Picture Play, July 1937

From Immigrant to Star

by Madeline Glass

You laugh at Mischa Auer to-day, but what do you know of the hardships and grief of his early life? This story will make you appreciate him more.

Transcript of article:

Press people are practically standing in line to interview Mischa Auer, yet when I told him on the telephone that I, too, wanted him to talk, for the benefit of Picture Play readers, he replied, “Love to!”

As it turned out we talked all over the Universal lot, beginning in the dining room, losing sight of each other in the publicity department- it was then that he went across the street to get something for his cold- were reunited on the set, and finished in his dressing room.

“Must be a nuisance to have some one tagging you and asking questions while you are trying to concentrate on your work,” I remarked.

“It would be much more than a nuisance if no one wanted to ask questions of me,” said he. “When interviewers stop coming-” Broad shoulders heaved in a telling shrug; brown eyes expressed apprehension.

But such apprehensions are for the far distant future. To-day Mischa’s popularity is growing by leaps and bounds- no pun on his astonishing monkey impersonation in “My Man Godfrey”- and he is kept so busy by the studios that he has no time to answer the deluge of fan letters that are pouring in on him.

“But now,” he told me, beaming, “I am to have a three-day vacation. I will have time to play with Tony. When I am working long hours, day after day, I hardly see him.”

Tony is his son, a 1934 model. Mischa wants him to become a sportsman, though not in the popular sense of the word.

“No football,” said he. “No brutal sports. I am something of an athlete- tennis, riding, aquatics- but I see nothing admirable in sports which involve cruelty. Life offers enough pain without our going out of our way to invite or inflict it.”

Mischa is well qualified to speak on this subject, as on many others. He has seen life at its rawest and most elemental. Every sort of disaster has followed and overtaken him; some have thrown him, but not for long. He not only survived tragedy and misadventure, but profited from them.

While Mischa was in his infancy his father died on the battlefield in the Russo-Japanese conflict. When but nine years of age his native Russia entered the World War. At twelve, revolution swept his country.

In the chaos he became separated from his mother, and for six months he drifted about the land with other homeless children. When finally restored to his mother, they decided to leave so turbulent a country, and eventually made their way to southern Russia where Mischa, despite his youth, enlisted in the British Expeditionary Forces. There his mother founded a refugee hospital which she managed until death from typhus ended her humanitarian work.

Very much alone now, Mischa prepared to go to Florence, Italy, where a friend of his mother was living. The sale of a few remaining jewels paid his train fare, but left nothing with which to buy clothing. Years of undernourishment had left his fifteen-year-old body undeveloped, and his British uniform hung baggily upon him.

“My clothes had to be disinfected before I was allowed to get on the train. They came out of the disinfecting process appallingly wrinkled- deep, crepey crinkles that ordinary water doesn’t produce. A kindly woman undertook to press them, but she had finished only one trouser leg when I had to put them on and hurry off. I got out of the train at Florence, all my worldly possessions tied in a steamer rug, and found an unpretentious cab to take me to an unpretentious hotel.

“The hotel manager had never seen anything like me. He walked around and around, inspecting me from every angle. My British uniform was a novelty, the War having ended eighteen months previously, and the unpressed trouser leg was several inches shorter than the other. Some one had given me a cane, and I stood there leaning on it, trying to look as dignified and nonchalant as possible.

“At length he let me register, and after putting my bundle in my room I set out to find mother’s friend. She had married, and I didn’t know her husband’s name, and I couldn’t think how I was to locate her. When I walked down the street people- Italians are naturally excitable- gathered and followed me, talking, and trying to solve the mystery of my appearance.

“An attendant at the city hall looked through the records which they keep on foreigners, and the friend’s name was listed there, also the name and address of her husband. She must have been astonished to find so strange-looking an object at her door, but she appeared not to notice. ‘Where is your mother?’ she asked. Only then did it seem fully to dawn on me that mother was dead. I dropped over in a faint.”

In New York lived one of Mischa’s grandparents, Leopold Auer, a music master of renown. He cabled passage money, and Mischa set out on a long journey. Through an error, no one met his boat, and he was sent to Ellis Island for three days.

Thereafter the sun of good fortune began to shine on the big-eyed immigrant. His grandfather adopted him, sent him to high school, introduced him to prominent people of the artistic world. He learned our language, among other things, and to dislodge a lingering accent studied pronunciation with a teacher of the deaf and dumb. Hour after hour he drilled himself in the correct pronunciation of English words. To-day his speech is free from accent, yet he frequently finds himself cast in roles where it is necessary for him to assume one. This minor irony amuses him, as do life’s other inconsistencies. Unembittered by his experiences, he is notably cheerful and optimistic.

For America, where he grew from stunted boyhood to strapping and distinguished maturity, he has the greatest affection. He laughed in recounting how, when he went to vote at the last presidential election, he found only one other voter at the poles- a fellow Russian.

The day’s work was finished and, getting into Mischa’s car, he drove us over to his dressing quarters. As befits his honestly earned success, Universal, where he is under contract, has provided him with a cheerful modern apartment. Sitting in a streamlined chair, still wearing his ochre make-up, he commented on the local Greek-Catholic church, where the atmosphere reminds him of his childhood in St. Petersburg; of conditions in Europe; of his work and family.

“My wife is American, born in Canada. When her parents heard that she was going to marry me they asked why she couldn’t find an American or Canadian instead. They had never met me, and such photographs as they saw were not reassuring. When I left the stage and got work in such pictures as ‘Lives of a Bengal Lancer’ and ‘Clive of India’ I was continually cast as assistant to the villain. When they saw stills from such productions, with me bundled up in whiskers or wearing the sly, oily expressions of polished cut-throats, they thought their daughter had lost her mind.

“I am very glad that I have got into comedy work. It gives me a feeling of satisfaction to see my pictures and realize that the character I am playing is affording amusement. I think the world needs all the humor it can get.” The fans, too, are glad that Mischa is no longer cast as “assistant to the villain,” and they are expressing their appreciation in an avalanche of mail.

“They do not send mere requests for my photograph, but write sizable, interesting letters,” said he gratefully. It was men like Frank Tuttle and Gregory La Cava who helped Mr. Auer get into picture work, and it is a pleased and admiring public that will keep him there.

#mischa auer#old hollywood#1930s hollywood#1930s#30s movies#picture play magazine#1930s film#classic film

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

c. 1922

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

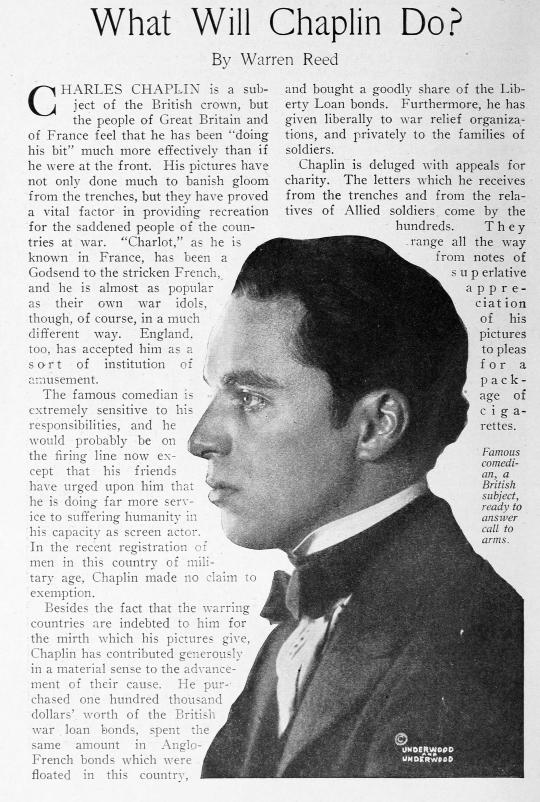

Picture-Play Magazine 1916

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tallulah Bankhead on the cover of the January 1933 issue of Picture Play Magazine.

#tallulah bankhead#1930s#picture play magazine#magazine cover#old hollywood#old magazines#old movies#old hollywood glamour#old movie stars#classic hollywood#classic film stars#old hollywood actress

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roscoe Arbuckle and Luke

Knitting Shocks for Slackers - Picture Play magazine

#1930s#1910s#1920s#1920s hollywood#silent film#silent comedy#silent cinema#silent era#silent movies#pre code#pre code hollywood#pre code film#pre code era#pre code movies#vintage hollywood#black and white#old hollywood#slapstick#roscoe arbuckle#luke the dog#picture play magazine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture Play, October 1935

#old hollywood#1930s#30s#1935#ruby keeler#mae west#kay francis#ginger rogers#norma shearer#clark gable#dick powell#fred astaire#ronald colman#robert montgomery#leslie howard#old movies#black and white#vintage#picture play#old magazines#magazines

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

from Picture Play Magazine, August 1925

original caption:

EVEN though it started with such a flare, Clara Bow's career has had its merely smoldering moments. But she bursts into new prominence in Lubitsch's "Kiss Me Again."

Photographer: Harold Dean Carsey

#clara bow#film magazine#fan magazine#classic hollywood#my edit#vintage style#portraits#classic movies#picture play#1920s#1925#old hollywod glamour#old hollywood#silent cinema#silent era#silent film#silent movie#classic cinema#classic film stars#classic film

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hit post limit yesterday which was kind of hilarious because 1) I didn't even know you could still do that 2) I have a time limit set for tumblr app on my phone, which means I reblogged 250 posts in less than three hours, and 3) I hit post limit at 2pm, and I had to stew in tumblr jail all freakin day

#chit chat#is the post limit still 250? i couldn’t find anything newer than 2017 on google#i was going wild about The Character and tumblr said nope! go touch grass!#so then i knitted a hat and i drew some pictures and i listened to half an audiobook#and i played some video games and i journaled and i read a magazine on my bed like a teen girl from the 90s#but i did not touch grass because it was like 12 degrees outside

11 notes

·

View notes