#pay gap

Photo

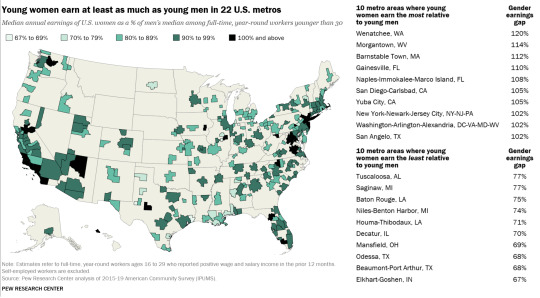

Young women now make more money than their male counterparts in several US metro areas including NYC and Washington DC.

254 notes

·

View notes

Photo

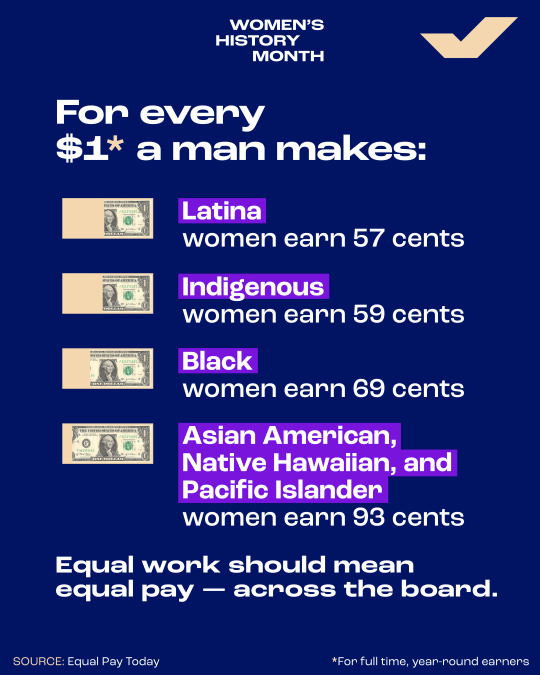

Today is Equal Pay Day. On average, a woman in the U.S. has to work until today — March 12th — to earn what a man was paid in the year prior. 🪙🙅🏽♀️💵

This #EqualPayDay, join us in bringing awareness to the gender wage gap, which is even wider for women of color.

The politicians WE elect can implement reforms that address pay inequality across industries. Make sure you’re registered to vote NOW at weall.vote/register.

#equal pay day#equal pay#equal pay today#pay gap#wage gap#pay inequality#register to vote#vote#voting#gender wage gap#equal work#equal work equal pay

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

It would take Diane Joyce nearly ten years of battles to become the first female skilled crafts worker ever in Santa Clara County history. It would take another seven years of court litigation, pursued all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, before she could actually start work. And then, the real fight would begin.

For blue-collar women, there was no honeymoon period on the job; the backlash began the first day they reported to work—and only intensified as the Reagan economy put more than a million blue-collar men out of work, reduced wages, and spread mounting fear. While the white-collar world seemed capable of absorbing countless lawyers and bankers in the 80s, the trades and crafts had no room for expansion. "Women are far more economically threatening in blue-collar work, because there are a finite number of jobs from which to choose," Mary Ellen Boyd, executive director of Non-Traditional Employment for Women, observes. "An MBA can do anything. But a plumber is only a plumber." While women never represented more than a few percentage points of the blue-collar work force, in this powder-keg situation it only took a few female faces to trigger a violent explosion.

Diane Joyce arrived in California in 1970, a thirty-three-year-old widow with four children, born and raised in Chicago. Her father was a tool-and-die maker, her mother a returned-goods clerk at a Walgreen's warehouse. At eighteen, she married Donald Joyce, a tool-and-die maker's apprentice at her father's plant. Fifteen years later, after working knee-deep in PCBs for years, he died suddenly of a rare form of liver cancer.

After her husband's death, Joyce taught herself to drive, packed her children in a 1966 Chrysler station wagon and headed west to San Jose, California, where a lone relative lived. Joyce was an experienced bookkeeper and she soon found work as a clerk in the county Office of Education, at $506 a month. A year later, she heard that the county's transportation department had a senior account clerk job vacant that paid $50 more a month. She applied in March 1972.

"You know, we wanted a man," the interviewer told her as soon as she walked through the door. But the account clerk jobs had all taken a pay cut recently, and sixteen women and no men had applied for the job. So he sent her on to the second interview. "This guy was a little politer," Joyce recalls. "First, he said, 'Nice day, isn't it?' before he tells me, 'You know, we wanted a man.' I wanted to say, 'Yeah, and where's my man? I am the man in my house.' But I'm sitting there with four kids to feed and all I can see is dollar signs, so I kept my mouth shut."

She got the job. Three months later, Joyce saw a posting for a "road maintenance man." An eighth-grade education and one year's work experience was all that was required, and the pay was $723 a month. Her current job required a high-school education, bookkeeping skills, and four years' experience— and paid $150 less a month. "I saw that flier and I said, ‘Oh wow, I can do that.’ Everyone in the office laughed. They thought it was a riot. . . . I let it drop."

But later that same year, every county worker got a 2 to 5 percent raise except for the 70 female account clerks. "Oh now, what do you girls need a raise for?" the director of personnel told Joyce and some other women who went before the board of supervisors to object. "All you'd do is spend the money on trips to Europe." Joyce was shocked. "Every account clerk I knew was supporting a family through death or divorce. I'd never seen Mexico, let alone Europe." Joyce decided to apply for the next better-paying "male" job that opened. In the meantime, she became active in the union; a skillful writer and one of the best-educated representatives there, Joyce wound up composing the safety language in the master contract and negotiating what became the most powerful county agreement protecting seniority rights.

In 1974, a road dispatcher retired, and both Joyce and a man named Paul Johnson, a former oil-fields roustabout, applied for the post. The supervisors told Joyce she needed to work on the road crew first and handed back her application. Johnson didn't have any road crew experience either, but his application was accepted. In the end, the job went to another man.

Joyce set out to get road crew experience. As she was filling out her application for the next road crew job that opened, in 1975, her supervisor walked in, asked what she was doing, and turned red. "You're taking a man's job away!" he shouted. Joyce sat silently for a minute, thinking. Then she said, "No, I'm not. Because a man can sit right here where I'm sitting."

In the evenings, she took courses in road maintenance and truck and light equipment operation. She came in third out of 87 applicants on the job test; there were ten openings on the road crew, and she got one of them.

For the next four years, Joyce carried tar pots on her shoulder, pulled trash from the median strip, and maneuvered trucks up the mountains to clear mud slides. "Working outdoors was great," she says. "You know, women pay fifty dollars a month to join a health club, and here I was getting paid to get in shape." The road men didn't exactly welcome her arrival. When they trained her to drive the bobtail trucks, she says, they kept changing instructions; one gave her driving tips that nearly blew up the engine. Her supervisor wouldn't issue her a pair of coveralls; she had to file a formal grievance to get them. In the yard, the men kept the ladies' room locked, and on the road they wouldn't stop to let her use the bathroom. "You wanted a man's job, you learn to pee like a man," her supervisor told her.

Obscene graffiti about Joyce appeared on the sides of trucks. Men threw darts at union notices she posted on the bulletin board. One day, the stockroom storekeeper, Tony Laramie, who says later he liked to call her "the piglet," called a general meeting in the depot's Ready Room. "I hate the day you came here," Laramie started screaming at Joyce as the other men looked on, many nodding. "We don't want you here. You don't belong here. Why don't you go the hell away?"

Joyce's experience was typical of the forthright and often violent backlash within the blue-collar work force, an assault undisguised by decorous homages to women's "difference." At a construction site in New York, for example, where only a few female hard-hats had found work, the men took a woman's work boots and hacked them into bits. Another woman was injured by a male co-worker; he hit her on the head with a two-by-four. In Santa Clara County, where Joyce worked, the county's equal opportunity office files were stuffed with reports of ostracism, hazing, sexual harassment, threats, verbal and physical abuse. "It's pervasive in some of the shops," says John Longabaugh, the county's equal employment officer at the time. "They mess up their tools, leave pornography on their desks. Safety equipment is made difficult to get, or unavailable." A maintenance worker greeted the first woman in his department with these words: "I know someone who would break your arm or leg for a price." Another new woman was ordered to clean a transit bus by her supervisor—only to find when she climbed aboard that the men had left a little gift for her: feces smeared across the seats.

In 1980, another dispatcher job opened up. Joyce and Johnson both applied. They both got similarly high scores on the written exam. Joyce now had four years' experience on the road crew; Paul Johnson only had a year and a half. The three interviewers, one of whom later referred to Joyce in court as "rabble-rousing" and "not a lady," gave the job to Johnson. Joyce decided to complain to the county athrmative action office.

The decision fell to James Graebner, the new director of the transportation department, an engineer who believed that it was about time the county hired its first woman for its 238 skilled-crafts jobs. Graebner confronted the roads director, Ron Shields. "What's wrong with the woman?" Graebner asked. “I hate her," Shields said, according to other people in the room. "I just said I thought Johnson was more qualified," is how Shields remembers it. "She didn't have the proficiency with heavy equipment." Neither, of course, did Johnson. Not that it was relevant anyway: dispatch is an office job that doesn't require lifting anything heavier than a microphone.

Graebner told Shields he was being overruled; Joyce had the job. Later that day, Joyce recalls, her supervisor called her into the conference room. "Well, you got the job," he told her. "But you're not qualified." Johnson, meanwhile, sat by the phone, dialing up the chain of command. "I felt like tearing something up," he recalls later. He demanded a meeting with the affirmative action office. "The affirmative action man walks in," Johnson says, "and he's this big black guy. He can't tell me anything. He brings in this minority who can barely speak English . . . I told them, 'You haven't heard the last of me.'" Within days, he had hired a lawyer and set his reverse discrimination suit in motion, contending that the county had given the job to a "less qualified" woman.

In 1987, the Supreme Court ruled against Johnson. The decision was hailed by women's and civil rights groups. But victory in Washington was not the same as triumph in the transportation yard. For Joyce and the road men, the backlash was just warming up. "Something like this is going to hurt me one day," Gerald Pourroy, a foreman in Joyce's office, says of the court's ruling, his voice low and bitter. He stares at the concrete wall above his desk. "I look down the tracks and I see the train coming toward me."

The day after the Supreme Court decision, a woman in the county office sent Joyce a congratulatory bouquet, two dozen carnations. Joyce arranged the flowers in a vase on her desk. The next day they were gone. She found them finally, crushed in a garbage bin. A road foreman told her, "I drop-kicked them across the yard."

-Susan Faludi, Backlash: the Undeclared War Against American Women

#susan faludi#female oppression#male entitlement#male violence#blue collar#women’s work#pay gap#sexism#misogyny#womens history#us history#amerika

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Within the transgender sample, those who were assigned female at birth have significantly lower incomes and are more likely to work part-time than those assigned male at birth"

But remember guys, "transwomen with male privilege are not a thing"

#transgender#trans#pay gap#gender pay gap#feminism#gender inequality#genderqueer#nonbinary#transfem#transmasc#transandrophobia#transmisogyny#anti transmasculinity#afab#amab#Lgbt#trans pride#queer#queer community#male privilege

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pay gap/female choices debate

I was watching this Youtube video the other day, and it pissed me off, but the main point of it was that there were these two men discussing how the pay gap isn't real because it all comes down to women's choices, citing really crappy examples as evidence. They clearly thought they were "owning the libs" too. They did this with 0 contextual analysis on why women make the decisions they do.

The first example they used was the Uber driver 7% pay gap, and how it's completely explained by three factors: (a) that women tend to be less experienced, (b) that men tend to drive faster, and (c) men drive in more lucrative locations. (This paper is Cook et al 20 by the way if you want to fact check me).

And yes, when you put it that way and remove all context for women's decisions, it certainly looks like that sort of moment. But think critically for like two seconds here:

Those more lucrative locations? The paper directly states that it's due to men's willingness to "drive in areas with higher crime and more drinking establishments". Of course men are more willing to do this! Your average woman is significantly more scared of being sexually assaulted, murdered, etc than your average man. She's going to avoid high crime areas because she's already in a vulnerable position (letting strangers into her car).

The fact that women have less experience? The attrition rate for female Uber drivers is substantially higher- 76.5% of women leave after six months, as opposed to 65% of male Uber drivers. I did found an article explaining why women self-select out of being in Uber or Lyft in the first place from Forbes. Quote, "...the job still involves driving alone and picking up strangers, often at night- situations that many women feel are dangerous. In interviews with eight female on-demand drivers, FORBES found that they usually feel safe but sometimes have doubts after troubling experiences and holes in safety policies." The article goes on to describe the experience of a female Uber driver in Atlanta, whose male customer tried to assault her. The company didn't handle the incident appropriately, and she never drove for Uber again. I'm willing to bet that this is the case for other female drivers too. The other women they interviewed (even those who are presumably still driving) described multiple similar experiences.

So, if you were a female Uber driver, you would probably leave around the six-month mark too. And as a result of this high attrition rate, the average female Uber driver will have less experience as compared to men.

And you know what? These other "gotcha" responses about the pay gap can probably be explained by outside factors too. Even in totally automated systems like Uber, where it does come down to female choices, those choices aren't being made in a freaking vacuum. It isn't just "haha pink lady brain can't drive as well", it's women don't feel safe and therefore make less money.

There's other scenarios where this is true as well. Women aren't climbing the corporate ladder as quickly as men? What else is going on? The Harvard Business Review found that more than half of men expect their careers to take precedence in a marriage- so if his is being prioritized always, what's happening to hers? When children get sick, women are ten times more likely to stay home from work to care for them (Kaiser Family Foundation). What does she miss in that lost time? When female scientists write papers, they are less likely than men to describe their accomplishments as *outstanding* or *unprecedented*, with the end result that their papers are cited less often. But it's because when women are socialized to be caretakers and to perform without complaint, this is the end result (Professional Development at Harvard). Worse, women who don't do this, and ask for raises/bonuses/etc, are more likely to be penalized than men (same source).

Yes, women sometimes make "decisions" which negatively impact their careers, but take it altogether. What makes men expect precedence of their wives? Misogyny. What makes men expect that their wives, regardless of their careers, will always nurse their sick kid? Misogyny. What makes women and their employers view female accomplishments as less valuable? You know the answer.

PS: two last things. The first is that I'm not trying to reduce the value of traditional "women's work". It isn't bad that women are taking care of their sick children, it's bad that men aren't doing it in equal numbers.

Secondly, if you're curious, there's this amazing professor named Claudia Goldin who I stumbled across while googling for this. She basically believes that the issue isn't direct discrimination from employers, but that the labor market encourages women to work differently. (And she's like 1000% more nuanced and career-specific than anything I just wrote). I put a link to an article about her below:

#feminism#Uber#pay gap#decisions aren't made in a vacuum lol#I had fun writing this#so it's worth it even if nobody reads#Feminist#womens rights

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

#september 2023#2023#articles#politico#Zachary Warmbrodt#strikes#auto workers strike#economics#pay gap

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

==

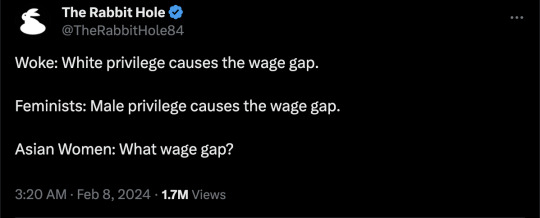

When a company actually underpays workers, it makes the news.

But if you're going to go, "see...?" you need to know that you're making the same argument as the Xian who says historical record of a local flood is proof of the extinction-level world-wide Genesis flood.

Meanwhile...

#The Rabbit Hole#pay gap#wage gap#pay gap myth#myth of the pay gap#earnings gap#myths and legends#religion is a mental illness

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The gender pay gap has barely closed in the United States in the past two decades. In 2022, American women typically earned 82 cents for every dollar earned by men. That was about the same as in 2002, when they earned 80 cents to the dollar. The slow pace at which the gender pay gap has narrowed this century contrasts sharply with the progress in the preceding two decades: In 1982, women earned just 65 cents to each dollar earned by men.

There is no single explanation for why progress toward narrowing the pay gap has all but stalled in the 21st century. Women generally begin their careers closer to wage parity with men, but they lose ground as they age and progress through their work lives, a pattern that has remained consistent over time. The pay gap persists even though women today are more likely than men to have graduated from college. In fact, the pay gap between college-educated women and men is not any narrower than the one between women and men who do not have a college degree. This points to the dominant role of other factors that still set women back or give men an advantage.

Read more: The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female is hard mode bc you get random debuffs and get less gold per quest

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

from this AP News article, printed Sept. 17, 2023...

"...However you slice the numbers, the gap between CEO pay and rank-and-file workers at all three companies is gigantic.

At GM, the median worker pay was $80,034 in 2022. It would take that worker 362 years to make Barra’s annual compensation.

At Ford, where the media pay $74, 691, it would take 281 years.

At Stellantis, with a median pay of 64,328 euros, it would take 365 years, although the company noted its its annual report that the disparity includes expenses related to Tavares’ one-time grant. Excluding that, the pay ratio is 298-1.

How extreme that disparity? It depends on the comparison.

It’s far above the typical pay gap at S&P 500 companies, which was 186-1 according to AP’s annual CEO pay survey, which uses data analyzed by Equilar.

And it’s astronomical by historical standards. According to a study of the 350 largest publicly traded U.S. firms by the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, the CEO-to-Worker pay ratio was just 15-1 in 1965...

...for that worker to make Musk’s “realized compensation” that year, it would take more than 18,000 years."

tl/dr...

'gigantic' and 'far above' and 'astronomical' differences between CEO compensation and workers salaries says it all

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#iceland#strike#women’s rights#gender equality#non binary#prime minister#equal pay#pay gap#ny times#article#sbrown82

13 notes

·

View notes

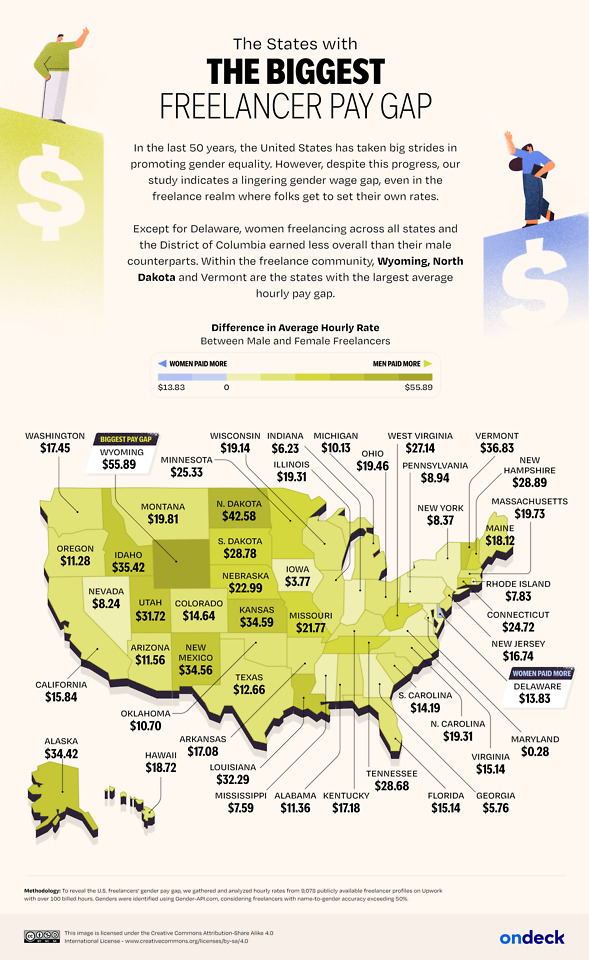

Photo

The Freelancer Pay Gap by State

Despite efforts to achieve pay equity, the gender pay gap remains a complex and ongoing challenge across America — even with freelancers who can set their own rates.

Data analysts at OnDeck analyzed the hourly rate charged by 9,078 U.S.-based freelancers on Upwork with over 100 billed hours to reveal the gender pay gap in America’s freelancing industry: https://www.ondeck.com/resources/pay-gap-gig-economy

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gender Pay Gap Is Largely Because of Motherhood

When men and women finish school and start working, they’re paid pretty much equally. But a gender pay gap soon appears, and it grows significantly over the next two decades.

So what changes? The answer can be found by looking at when the pay gap widens most sharply. It’s the late 20s to mid-30s, according to two new studies — in other words, when many women have children. Unmarried women without children continue to earn closer to what men do.

But even married women without children earn less, research shows, because women are more likely to give up job opportunities to either move or stay put for their husband’s job. Married women might also take less intensive jobs in preparation for children, or employers might not give them more responsibility because they assume they’ll have babies and take time off.

It is logical for couples to decide that the person who earns less, usually a woman, does more of the household chores and child care, Ms. Kerr said. But it’s also a reason women earn less in the first place. “That reinforces the pay gap in the labor market, and we’re trapped in this self-reinforcing cycle,” she said.

Some women work less once they have children, but many don’t, and employers pay them less, too, seemingly because they assume they will be less committed, research shows.

Even when mothers cut back at work, they are not paid proportionately less. When their pay is calculated on an hourly basis, they are still paid less than men for the hours they work, Ms. Goldin has shown in previous work. Employers, especially for jobs that require a college degree, pay people disproportionately more for working long hours and disproportionately less for working flexibly.

To achieve greater pay equality, social scientists say — other than women avoiding marriage and children — changes would have to take place in workplaces and public policy that applied to both men and women. Examples could be companies putting less priority on long hours and face time, and the government providing subsidized child care and moderate-length parental leave.

According to the data, Ms. Kerr said, college-educated women make about 90 percent as much as men at age 25 and about 55 percent as much at age 45.

The new working paper, which covered the broadest group of people over time, found that between ages 25 and 45, the gender pay gap for college graduates, which starts close to zero, widens by 55 percentage points. For those without college degrees, it widens by 28 percentage points.

The pay gap is larger for college graduates because their earnings are higher, and men dominate the highest-paying jobs. These jobs also place more value on long, inflexible hours.

People without college degrees start out with a slightly larger pay gap, but it is smaller throughout their careers. Part of the reason is that less educated men have fewer high-paying job options than they used to. “The pay gap is not because non-college-educated women do so well, but because non-college-educated men are not doing well,” Ms. Kerr said.

Twenty-seven percent of the overall pay gap is from men being more likely to jump to higher-paying firms, the economists found. When married women leave jobs, they are less likely to get a big pay bump as a result. Previous research has found they are more likely to leave without another job lined up; they may move for their husband’s job or take time off with children.

But the bulk of the pay gap — 73 percent, they found — is from women not getting raises and promotions at the rate of men within companies. Seniority and experience seem to pay off much more for men than for women.

“On every possible front, women are getting the short end of the stick,” Ms. Kerr said. “Whether they’re changing jobs or trying to stick with the current employer, the returns are always smaller.”

The average college-educated man, for instance, improves his earnings by 77 percent from age 25 to 45, while similar women improve their earnings by only 31 percent. Men without college degrees increase their earnings much faster than similar women in the first decade of their careers, but by age 45, women catch up.

Even women who catch up, however, pay a long-term price. They’ve lost a significant amount of pay — in wages, raises and retirement savings — along the way.

This is depressing enough as it is, and that's assuming the data is only on cis white women. Like why even try in this world

#i know this is kind of an older article (2017) i came across it while researching for a report#misogyny#pay gap#america

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drive, executive ability, and a single-mindedness of purpose became enduring characteristics of Susan Anthony. She was impatient with whatever did not contribute directly to the battles she waged in her various campaigns for reform. She began as a teacher at the age of seventeen, and for many years she was a critical observer and then vigorous participant at teachers'-association conventions.

An early example of her courage and ability to press to the main point of an argument can be seen in her role at the 1853 state convention of schoolteachers. At this time women teachers could attend but could not speak at the convention meetings. Susan listened to a long discussion on why the profession of teaching was not as respected as those of law, medicine, and the ministry. When she could stand it no longer, she rose from her seat and called out, "Mr. President!" After much consternation about recognizing her, she was asked what she wished. When informed that she wished to speak to the question under discussion, a half-hour's debate and a close vote resulted in permission. Then she said:

“It seems to me, gentlemen, that none of you quite comprehend the cause of the disrespect of which you complain. Do you not see that so long as society says a woman is incompetent to be a lawyer, minister or doctor, but has ample ability to be a teacher, that every man of you who chooses this profession tacitly acknowledges that he has no more brains than a woman? And this, too, is the reason that teaching is a less lucrative profession, as here men must compete with the cheap labor of woman. Would you exalt your profession, exalt those who labor with you. Would you make it more lucrative, increase the salaries of the women engaged in the noble work of educating our future Presidents, Senators and Congressmen.”

Susan's point on the wage scale of occupations in which many women are employed is as pertinent in the 1970s as it was in the 1850s. Equal pay for equal work continues to be seen as applying to equal pay for men and women in the same occupation, while the larger point of continuing relevance in our day is that some occupations have depressed wages because women are the chief employees. The former is a pattern of sex discrimination, the latter of institutionalized sexism.

-Alice S. Rossi, The Feminist Papers: From Adams to de Beauvoir

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

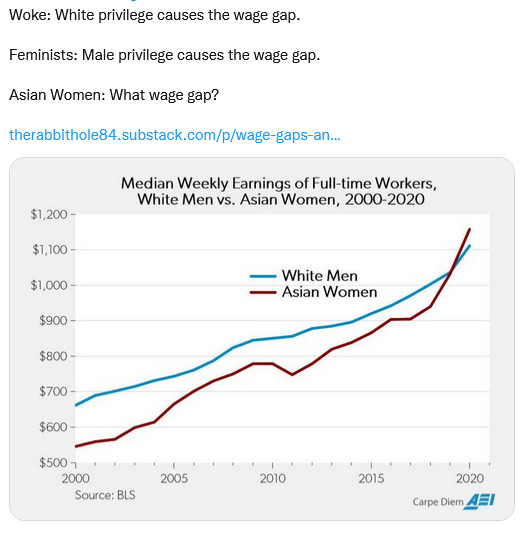

https://therabbithole84.substack.com/p/wage-gaps-and-the-discrimination

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy women's history month. Remember women's rights don't stop at legality. Female dominant jobs are undervalued and underpaid. The "pay gap" is actually a wage gap and it is directly caused by the devaluement of women's work, social barriers put in place that prevent women from achieving higher and social conditioning that teaches women to be afraid to do things like ask for a raise!

You can acknowledge this and simultaneously acknowledge the lack of working rights that affect certain male dominant jobs. The two are not mutually exclusive.

6 notes

·

View notes