#oniisama e

Text

The original first italian edition of Oniisama, 1995

#submission#courtesy of my dad's partner's collection she passed onto me#just found it today while reorganising#i thought you might appreciate it💕💕#oniisama e

33 notes

·

View notes

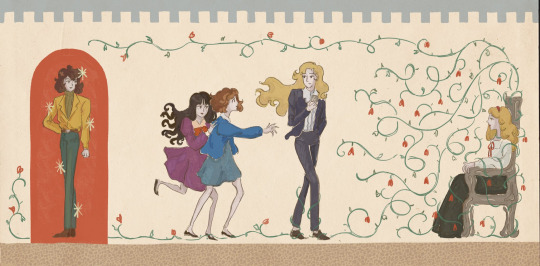

Text

ma chère poupée

commissions / ig

#this is like my third post in a row with a french caption i promise i'll stop lol#oniisama e#dear brother#rei asaka#nanako misonoo#me art

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

🕷️Oniisama E (1991)🕷️

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

おにいさま…おにいさま…涙が止まりません!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#90s anime#anime retro#retrowave#lofi aesthetic#90s#oniisama e#synthwave#anime#vaporwave#retro aesthetic#aesthetic#lofi vibes#landscape#city pop#anime gif

818 notes

·

View notes

Text

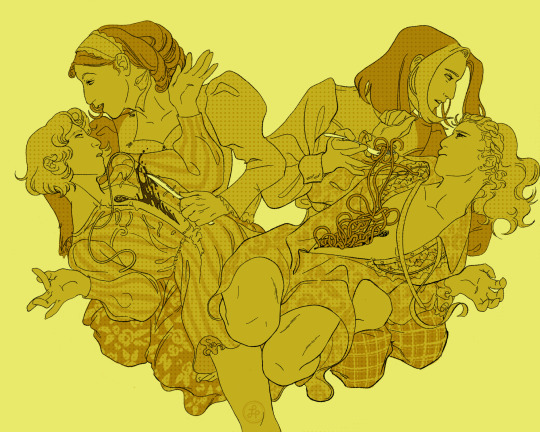

table knife.

#myart#on my piss yellow siblings saga.#mostly a simplification of one of those oniisamae pc drawings im never finishing post lol.#oniisama e#dear brother#rgu#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#sku#fukiko ichinomiya#rei asaka#nanami kiryuu#touga kiryuu

562 notes

·

View notes

Text

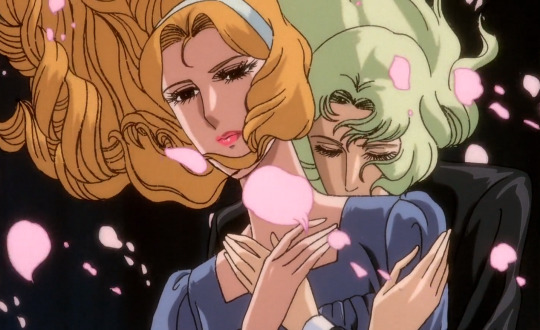

Fleeting love

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

#I put more focus and effort into this than my college assignment#oniisama e#dear brother#rei asaka#nanako misonoo

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

oniisama e, dir. osamu dezaki (1991) + persona, dir. ingmar bergman (1966)

429 notes

·

View notes

Text

684 notes

·

View notes

Text

🕷️Oniisama E, 1994🕷️

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

#anime retro#90s anime#90s#lofi aesthetic#retrowave#vaporwave#synthwave#80s anime#anime#80's#oniisama e#lofi

376 notes

·

View notes

Text

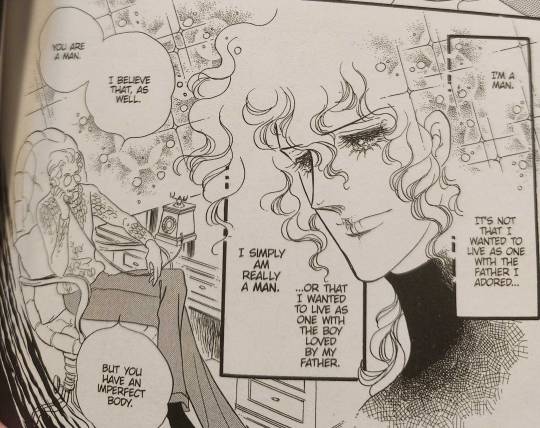

Transmasculinity and queer sexuality in the works of Ikeda Riyoko

Content Warning: Discussion of transphobia and suicide

Spoilers for Dear Brother, The Rose of Versailles, and Claudine

Ikeda Riyoko—perhaps the most famous member of the “year 24 group” that played a large part in creating the foundations of the shoujo manga genre—is often credited with laying the groundwork for depictions of queer characters in shoujo, and in particular with creating the archetype of the gender-bending heartthrob heroine, or “girl prince.” Building on earlier representations of butch or transmasculine characters in early shoujo manga such as Princess Knight, and the Takarazuka theater tradition of the otokoyaku male role actor, Ikeda’s enormously popular gender non-conforming heroes—Lady Oscar from The Rose of Versailles, Rei from Dear Brother, Julius from the Window of Orpheus, and the titular character of Claudine—helped to establish that there was a major mainstream audience excited to cheer for a hotheaded, androgynous tomboy with a heart of gold. Lady Oscar in particular has fingerprints all over the history of anime and manga, from a gender-bending cameo in Pokémon to serving as the inspiration for iconic characters like Tenjou Utena.

When I first read The Rose of Versailles last year, I expected its depictions of queer and transmasculine characters to be somewhat limited—after all, the comic was written for mainstream audiences and a mainstream publisher in the 1970s. But across Ikeda’s work, I was deeply surprised with the level of care and nuance with which Ikeda approaches transmasculine love stories. While there is obviously a lot about Ikeda’s portrayal of transmasculine characters that feels dated to modern audiences (for example, her comics often do fall back on “biological” ideas of women’s weakness and emotionality, and sometimes psychologize her character’s genders in uncomfortable ways), I was surprised by how much of these comics still hit for me today. What makes them work for me is both the extreme pathos with which Ikeda writes transmasculine character’s experiences of rejection—and, at rare moments, gender euphoria —but also the fact that her trans characters are not simply given a one-size fits all born-in-the-wrong-body narrative. Instead, they are each portrayed as unique individuals with varied personal relationships to their gender, their sexuality, and the historical context of the society they live in.

Read it at Anime Feminist!

#riyoko ikeda#ryoko ikeda#rose of versailles#berubara#versailles no bara#lady oscar#dear brother#oniisama e#claudine#classic shoujo#shoujo#articles#asuka rei

317 notes

·

View notes