#northern spicebush

Text

A few photos above from an early morning hike at the Friendship Hill National Historic Site near Pt. Marion, Pennsylvania. If you want to learn more about the history of this sprawling estate, you can go to this link or search for prior posts from the main search page of my Tumblr blog. In addition to the historic homestead of Albert Gallatin, the park features ten miles of hiking trails through verdant oak-hickory and riparian forests. This time of year, the Central Appalachian forest is rich with fungi, legumes, berries, and the loveliest orb-weavers imaginable.

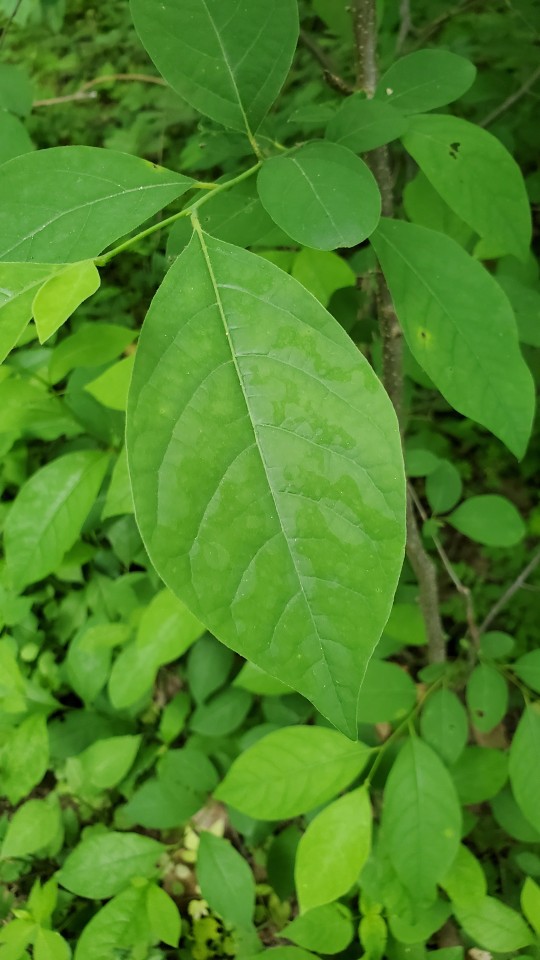

From top: wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia), also known as yellow ironweed, a late summer aster so named because the petioles of its leaves run down the plant's stem; northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin), a gorgeous native shrub whose bright red berries in late summer are followed by the most extraordinary gold foliage in the fall; orange mycena (Mycena leaiana), a lovely, gregarious fungi of deciduous logs whose pigment has shown antibacterial and anti-cancer properties; the ripened but dangerously toxic berries of pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), whose young leaves are used by mountain folk to make poke sallet (but only after repeated cleansings to remove the toxins); American hog-peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata), a lovely twining vine whose roots and ground nut are edible; cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata), also known as green-headed coneflower and wild goldenglow, a close relative of black-eyed Susan with gorgeous, pinnately-dissected leaves (the leaf photo also shows the characteristic tri-foliate leaf pattern of hog-peanut); zig-zag goldenrod (Solidago flexicaulis), one of two adorable woodland goldenrods that grow in this area (the other being blue-stemmed goldenrod), both of which produce clusters of brilliant yellow flowers in both their leaf axils and at the ends of their stems; steeplebush (Spiraea tomentosa), also known as hardhack, which produces delicate plumes of pink flowers in late summer; a spined micrathena (Micrathena gracilis), which has ensnared a fly in her web; and an arrowhead orb weaver (Verrucosa arenata), also known as a triangle orb-weaver, a sparkling gem of an arachnid that reels in its prey like a fisherman dragging in a net.

#appalachia#vandalia#wildflowers#flora#summer#arachnid#pennsylvania#friendship hill national historic site#fungi#orange mycena#wingstem#yellow ironweed#northern spicebush#pokeweed#american hog-peanut#cutleaf coneflower#green-headed coneflower#wild goldenglow#zig-zag goldenrod#steeplebush#hardhack#orb-weaver#spider#spined micrathena#arrowhead orb-weaver#triangle orb-weaver

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern Spice Bush - Lindera benzoin

This small understory shrub/tree is a lovely aromatic spring bloomer. Around April, the understory of less disturbed-mesic eastern forests are typically blanketed by a yellow hue, the flowering habit of this species is bountiful so it makes a great garden species. Additionally the leaves and bark make a wonderful tea, the leaves historically served as an alternate for allspice seasoning for early settlers.

As far as ecology, this species serves as host for several butterfly and moth species. Most notably the spicebush swallowtail, a lovely black winged species with light blue tints around the lower wing. Their caterpillar stage typically hides between folded leaves and has the appearance of large eyes (look them up they're very interesting). The leaves are used as fodder for deer and the berries serve many bird species, I often have trouble finding berries because it's such a popular food source.

#native plant profiles#northern spicebush#lindera benzoin#north eastern american native plants#new jersey#forest#understory shrubs#nature#spring

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

work finds from this day in 2019: bloodroot, spring beauties, star chickweed, northern spicebush, dekay’s brownsnake, red-backed salamander, dimpled trout lily, oconee bells

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@liberhoe Possible fadingflea kits?

HarlequinKit (left)

yellow harlequin/corydalis

Molly

AmaranthKit’s favourite flower

Bees like this flower, and their oldest sister is TawnyKit who is named after the Tawny Mining Bee

WeepingKit (mid)

weeping milk cap mushrooms

Tom

the first thing FleaThistle grew in the dark forest was this kind of mushroom and it was the first conversation he had with FadingStar.

WeepingKit also sounds good with FadingStar.

SpiceBushKit (right)

northern spicebush

Molly

plant FleaThistle used to poison his abusive adoptive mother, to him it symbolized change

Spicebush symbolizes doing things early, swiftly, and ahead of time

I imagine FoxgloveKit would be the runt in this litter

Obviously it’s up to you if they do have another full litter, I’m just throwing ideas out there :) I mostly just made these for fun

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The February 2023 issue of Washington Gardener Magazine is out. Inside this issue: · 17 Award-winning Garden Photos · Native Northern Spicebush Plant Profile · Great Gardening Books Reviewed · Six Tips for Long-Lasting Cut Tulips · Seed Potatoes vs. Potato Seeds · “Almost” Native Common Dandelions · Cherry Laurel Substitutes · Two New Tomatoes from Burpee · Butterfly Gardening in the Shade · Meet Martha Pindale, Horticulturist and Instructor · Philly Flower Show Trip Details · DC-MD-VA Gardening Events Calendar · and much more… Note that any submissions, event listings, and advertisements for the March 2023 issue are due by March 5. >> Subscribe to Washington Gardener Magazine today to have the monthly publication sent to your inbox as a PDF several days before it is available online. You can use the PayPal (credit card) online order form here: http://www.washingtongardener.com/index_files/subscribe.htm (at Washington D.C.) https://www.instagram.com/p/Co50VjFOQAA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Spicebush - Lindera benzion - turning from flowers to leaves

#spring#plant id#lindera#lindera benzoin#spicebush#northern spicebush#flowers#shrubs#leaves#new leaves

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warmer Springs and Earlier Birds

by Bonnie McGill

Male Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) by Jonathan Eckerson via Macaulay Library.

Male Red-winged Blackbirds! For me, their calls and bright red shoulders are one of the signs that spring is really here. Mind you, this is no subtle sign of spring that takes an expert naturalist to notice. No, this is a sign of spring that slaps you across the face, as if spring is calling, “I’m here! CONK-A-REE! Look at me!” Next time you drive past a wetland area with cattails, there is a good chance you’ll see one or more showing off their red shoulders (the brown females are beautiful too). Red-winged Blackbirds have been back in western PA and announcing their territorial claims since March. Whether you live in the country or the city, bird watching is a great way to observe the change in seasons and connect with the nature around you (and in you).

As a member of the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership (CRSP) team I’ve been gathering evidence-based stories of how climate change is impacting natural processes in western PA. Since this week is the City Nature Challenge, folks might be paying closer attention to birds, creating an opportunity for museum scientists to explain what migratory songbirds in our region can teach us about climate change.

Since 1961 scientists at the museum’s Powdermill Avian Research Center (PARC) in Pennsylvania’s Laurel Highlands have been monitoring birds. In that time they have captured, studied, marked, and released almost 800,000 birds! This week, for example, PARC’s mist nets are temporarily capturing birds like the Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, House Wren, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, American Redstart, and Wood Thrush.

Migratory birds that are part of the PARC long term dataset (clockwise from left): Wood Thrush, Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, and Ruby-throated Hummingbird. All of these species are breeding earlier in the year in response to climate change that has already occured. Photos courtesy of Powdermill Avian Research Center.

All of these species are migratory--spending the winter in the southern US, the Caribbean, Central America, and/or South America. Many fly across the Gulf of Mexico (!) on their way north in the spring. All of these birds share another trait--they are nesting earlier in the year than they once did. We will follow the Wood Thrush as an example of how many birds are responding to the warming climate.

The artwork in this blog post is by the author and part of an infographic depicting the information written here.

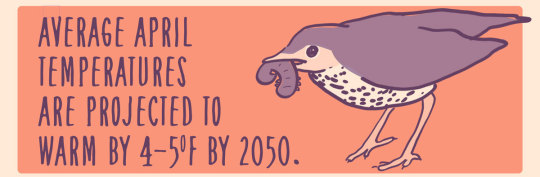

PARC’s unique 50 year dataset allows scientists to study how birds respond to long term changes, including the warming climate. Average April temperatures in the Laurel Highlands have already increased by two degrees Fahrenheit since the 1960s, and are projected to warm by another four to five degrees Fahrenheit by 2050. Warmer springs trigger earlier plant budburst. Insects, especially caterpillars, feast on buds and young leaves, which have less toxins than mature leaves. Caterpillars are the breakfast of champions (among birds). So, migratory songbirds, including the Wood Thrush, need to synchronize their northward movement with the budburst. This means an earlier arrival, according to the calendar, at points all along their migration route.

Wood Thrushes arrive from Central America five days earlier than they did in the 1960s. Research suggests that migratory birds respond to temperature cues along their migration route and speed up (warmer temperatures) or slow down (cooler temperatures). Birds may be responding to temperature directly or indirectly via other temperature-dependent cues such as wind speed and direction and spring leaf out.

Early arrival is not the only adjustment Wood Thrushes are making, however. The birds are also making their nests and hatching young earlier. Wood Thrushes are nesting 22 days earlier than they did in the 1960s. All four of the bird species in the photo above are breeding earlier. Within the web of organisms that supplies food for birds, May 19 of the present feels like June 11 of the 1960s. The earlier nesting in response to a warming climate means birds that normally hatch and rear multiple broods per breeding season, such as House Wrens and Northern Cardinals, may have greater reproductive capacity. PARC research shows that Gray Catbirds and Northern Cardinals are having more young in warmer springs, but other multi-brood species such as House Wrens and Common Yellowthroats are not.

While birds seem to be keeping pace with climate change now, they may not be able to in the future. Their capacity to adjust migratory and reproductive behavioral traits in response to climate change is finite. Also, we’ve already lost an estimated 3 billion North American birds since 1970 due to factors including habitat loss, insect declines, pesticide use, and predation by domestic cats. Now climate change is making bird survival even more difficult. The capacity of bird populations to evolve in response to climate change is also limited -- climate change in the Anthropocene is happening much more rapidly than climate change in past epochs, many times faster than evolution can keep up. The good news is we can help birds, ecosystems, and ourselves by taking action to reduce the severity of climate change.

Here are three ways individuals and communities can help birds by mitigating climate change:

1) Conserve habitat: Habitats like forests, wetlands, and prairies provide food and shelter for birds while the plants and soils remove and store carbon away from the atmosphere. These habitats are needed throughout birds’ migratory ranges. Create habitat by reducing lawns and planting native plants. For example, many birds enjoy eating the fruits of spicebush, elderberry, and black cherry, which are native to western Pennsylvania. You can find more bird-friendly plants native to your area at https://www.audubon.org/plantsforbirds.

2) Renewable energy: A just transition to renewable energy sources like properly-sited wind* and solar will reduce greenhouse gas emissions, provide local jobs, improve air quality, and help protect birds and people from climate change. *The National Audubon Society supports properly-sited wind energy.

3) Eat your vegetables: A more plant-based diet is an impactful way to reduce greenhouse gas footprints. Also, choosing food that is grown with less pesticides, and using less pesticides in the stewardship of your garden, helps support the survival of insects that are food for birds. Reductions in demand for pesticides also reduces their manufacture, which further reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Learn more from Project Drawdown.

So get out there, find the signs of spring that are gentle (Trout Lilies) and not-so-gentle (Red-winged Blackbirds), log them in iNaturalist for the City Nature Challenge, and talk with your family and your community about how you can implement one or two (or three!) of the actions suggested above!

You can also read this as an infographic here.

Thank you to the many folks who helped with the development of this blog post and infographic: Luke DeGroote, Mary Shidell, and Annie Lindsay at PARC; the Laurel Highlands network of the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership; Nicole Heller; Taiji Nelson; and Sarah Crawford.

Bonnie McGill, Ph.D. is a science communication fellow for the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership and based in the Anthropocene Studies Section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smoothie Ideas

Who asked? No one. But if I had access to all of these and a good amount space to work with as well as room in a freezer, and a good blender/food processor, this is what I would do. All plant parts in equal amounts. Plus plain yogurt and silky tofu for texture. And maple syrup, honey, and cane sugar for added sweetness.

Red smoothie

honey: fall

apples:

Cortland

empire

Fuji

honeycrisp

Ida red

jazz

red delicious

McIntosh

starkrimson

pacific rose

pinata

pink lady

red crapbapple fruits and blossoms

red prince

bearberry

blood orange

buffalo berry

cherries:

Bing

black

choke

pin

sand

sour

cherry tomatoes:

black cherry

cherry

grape

Chinese bayberry

coffee cherry

cranberries:

small

large

lingonberry

dogwood fruits:

bunchberry

cornel cherry

Kousa

false Solomon’s seal fruit:

Canada mayflower

false Solomon’s seal

starry false Solomon’s seal

ginseng berries:

American

Chinese

goji

haws:

Chinese

cockspur

common

downy

dotted

fireberry

mayhaw

Jack-in-the-pulpit berry

Japanese barberry

mace

partridge berry

peppers:

habanero

red bell

plumcot

pomegranate

purple mombin

raspberries and blackberries:

Allegheny blackberry

American red raspberry

Arctic raspberry

black raspberry

Canadian blackberry

common dewberry

dwarf red blackberry

European blackberry

European red raspberry

glandstem blackberry

loganberry

Pennsylvania blackberry

purple-flowered raspberry

setose blackberry

swamp dewberry

thimbleberry

trailing raspberry

red bean

red elderberry

red grape

red jujube

red mulberry

red plum

redcurrants:

European

northern

skunk

reishi

rosehips and rose petals

spicebush berry

strawberries:

garden

Virginia

woodland

sumacs:

fragrant

shining

smooth

staghorn

tamarillo

tulip petal

viburnum berries:

highbush cranberry

snowball tree berry

squashberry

wintergreen berry

yew aril

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Made my first concerted effort to start native plants from seed last year- collected a variety, potted them, and buried the pots over the winter so they could naturally stratify. Tragically, the squirrels got my sprouted kingnut hickory and burr oak (they must have thought they’d died and gone to heaven lol), but the smaller sprouts are doing well!

First pic is brown dragon (aka Jack-in-the-Pulpit, Arisaema triphyllum) and green dragon (Arisaema dracontium), but I don’t remember which pots are which. Other pics in order are northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin), wooly pipevine (aka Dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochia tomentosa, the only seed I bought bc I couldn’t find any wild ones), something I don’t remember what it is (was busy with work and didn’t label anything rip me), and some volunteer stout blue eyed grass (itty bitty native irises, so cute omg) in the bed next to the pots.

I’m pumped for these! Especially the pipevine! Hopefully they’ll all do well, I can give some to neighbors, and maybe we’ll get pipevine swallowtails! I’m a little puzzled more species didn’t come up though- basswood, beech, wahoo, american bittersweet, zigzag spiderwort, ground cherry, and blatternut are all unaccounted for. Blatternut is pickier, but the others shouldn’t be too hard to start? My pawpaw seeds will hopefully sprout in June or July, so maybe there’ll be some other late bloomers yet!

And I’ll def make a cage for next year’s sprouted tree nuts, damn!

#plants#plantblr#baby plants#seedlings#plant starts#native plants#permaculture#habitat restoration#backyard habitat#biodiversity#indiana#midwest#rewilding#homesteading#sorta#Great Lakes region#native landscaping#kill your lawn#department of unauthorized forestry#gorilla gardening#thrush laughs#thrush snaps#photoset

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photos from a late summer bike ride on the Mon River Trail. With autumn just around the corner, the climatic, life-sustaining ceremonies of the season have taken on a frantic, bittersweet urgency, from the proliferation of late summer blooms to the frantic chirrups of insects in search of mates before they succumb to the first frost of October. As the deep greens of summer fade and begin to sacrifice themselves to a fiery self-immolation, I salute Nature’s relentless push to plant the seeds of next year’s renewal.

From top: broadleaf arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia), also known as duck-potato and wapato, an attractive aquatic plant whose edible tuber was an important source of starch for Native Americans; great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica); a showy relative of cardinal flower with blue, split-lip flowers; blue mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum), also known as wild ageratum and blue boneset, an unusual late summer aster with disc flowers only; tall coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris), also known as tall tickseed, a grand, stately perennial up to 8 feet tall with distinctive tripartite leaves; a goldenrod soldier beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus) navigating a wingstem flower (Verbesina alternifolia); northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin), a colonizing shrub whose luminous yellow leaves in fall contrast with its brilliant-red, aromatic berries; and pale-leaved sunflower ( Helianthus strumosus), a perennial sunflower whose leaves are mostly opposite in arrangement with long petioles and pale undersides.

#appalachia#vandalia#west virginia#mon river trail#late summer#life#renewal#flora#wildflowers#insects#sagittaria latifolia#broadleaf arrowhead#duck-potato#wapato#lobelia siphilitica#great blue lobelia#conoclinium coelestinum#blue mistflower#wild ageratum#blue boneset#coreopsis tripteris#tall coreopsis#tall tickseed#chauliognathus pensylvanicus#goldenrod soldier beetle#verbesina alternifolia#wingstem#Lindera benzoin#northern spicebush#helianthus strumosus

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spicebush in Spring - April 8th 2023

#nature#forest#northern spicebush#new jersey#original phography#photographers on tumblr#njlocal#spring flowers#north eastern american native plants#the green is japanese barberry im afraid to go in there because the coyotes dump bones there#there is also bamboo we cant get rid of on the right

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

9/6/21

0 notes

Text

Invasive shrubs in Northeast US forests grow leaves earlier and keep them longer

https://sciencespies.com/nature/invasive-shrubs-in-northeast-us-forests-grow-leaves-earlier-and-keep-them-longer/

Invasive shrubs in Northeast US forests grow leaves earlier and keep them longer

The rapid pace that invasive shrubs infiltrate forests in the northeastern United States makes scientists suspect they have a consistent advantage over native shrubs, and the first region-wide study of leaf timing, conducted by Penn State researchers, supports those suspicions.

With the help of citizen scientists spread over more than 150 sites in more than 20 states, researchers collected thousands of observations over four years of exactly when both invasive and native shrubs leaf out in the spring and lose their leaves in the fall. The study area was expansive, stretching from southern Maine to central Minnesota south to southern Missouri, to North Carolina.

“Eastern North America is the recipient of more invasive shrub species into natural areas than any other geographic region of the world,” said lead researcher Erynn Maynard-Bean, postdoctoral researcher in the College of Agricultural Sciences, working under the guidance of Margot Kaye, associate professor of forest ecology. “Invasive shrubs are growing in both abundance and in the number of species established at the expense of many types of native species.”

The researchers reported in Biological Invasions that invasive shrubs can maintain leaves 77 days longer than native shrubs within a growing season at the southern end of the area studied. The difference decreases to about 30 days at the northern end of the study area. At the southern end of the study area, the time when invasive shrubs have leaves and native shrubs do not is equally distributed between spring and fall; in the northern reaches of the study area, two-thirds of the difference between native and invasive growing seasons occur in fall.

The longer period with leaves gives invasive plants an advantage in acquiring more energy from sunlight and their leaves create shade in early spring and late fall that may limit growth of native species, such as forest ephemeral wildflowers, Maynard-Bean explained. “This helps explain their negative impact on native tree regeneration, plant diversity and abundance,” she said. “But invasive shrubs also have a negative impact on communities of animal species sensitive to light and temperature, such as bees, butterflies and amphibians.”

Small, local studies in Northeast forests have shown that invasive shrubs have leaves longer than native shrubs. However, because the phenomenon — known as extended leaf phenology — varies geographically, the degree to which it benefits invasive shrubs across the region had previously been unknown.

The difference between native plants and invasive plants having leaves is not consistent, Maynard-Bean noted. It varies, depending on latitude, species studied and weather for the study period.

“But with the help of citizen scientists with USA National Phenology Network watching plants with us from around the eastern U.S., we found a pattern of greater extended leaf phenology as you move south,” she said. “This provides a unified framework for connecting local-scale research results from different parts of the eastern U.S. that had previously not agreed with one another.”

With the goal of understanding on-the-ground implications for eastern deciduous forest ecosystems, the researchers chose common, widespread species that co-occur in forest understories. Native shrubs followed in the study included alternate-leaf dogwood, flowering dogwood, gray dogwood, spicebush, mapleleaf viburnum, southern arrowwood, hobble-bush and black haw. Invasive shrubs native to Europe or Asia followed in the study included Japanese barberry, burning bush, multiflora rose and several species of honeysuckles and privet.

About 800 citizen scientists collected more than 8,000 observations of leaf timing for 804 shrubs at 384 sites, from 2015 through 2018. In addition, Maynard-Bean made observations at three sites in Pennsylvania.

The patterns of extended leaf phenology for invasive shrubs compared to native shrubs found in this study have important implications for policy and management, according to Kaye, whose research group has been evaluating invasive shrubs in Northeast forests for more than a decade. She pointed out that invasives included in this study are still commonly used for horticultural purposes in some states but are banned in others.

“The presence of this phenomenon may serve as a predictive trait for the invasion potential of new horticultural specimens,” Maynard-Bean said. “From a management perspective, extended leaf phenology makes invasive shrubs an easier ‘green target’ in the spring and fall for detection, removal and treatment, which can protect dormant, non-target native species.”

Story Source:

Materials provided by Penn State. Original written by Jeff Mulhollem. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

#Nature

#08-2020 Science News#2020 Science News#Earth Environment#earth science#Environment and Nature#Nature Science#News Science Spies#Our Nature#outrageous acts of science#planetary science#Science#Science Channel#science documentary#Science News#Science Spies#Science Spies News#Space Physics & Nature#Space Science#Nature

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Idk if emoji asks are still open, but.. 💐bouquet for FleaThistle and AmaranthKit?

Thank you for asking! I’m 99% sure this is an ask from my in person friend because of me talking about AmaranthKit a ton.

💐 BOUQUET - create a bouqet for them! what do those flowers mean? are any of the flowers their particular favourite?

FleaThistle

Queen Anne’s lace - safety, sanctuary

chicory - perseverance and endless waiting

goldenrod - hope and joy

northern spicebush - the plant he used to poison someone

blue marguerite daisy - long lasting trust, honesty, loyalty

Sensitive Fern - delicacy. The plant he killed HornetLeg over and the plant he sought comfort in. His favourite.

AmaranthKit

Clematis - the beauty of ingenuity or the trait of artifice.

Yellow harlequin/corydalis - short lived

Dianthus “green ball” - Renewal, youth, good fortune, optimism. Her favourite because she likes batting the flowers around like moss balls.

Amaranth - rebirth, immortality, purity, unfading. I think it would be cute if she was slightly allergic to them so she just sneezes whenever near them but still loves them

(@liberhoe @residents-of-the-darkforest)

#warrior cats#warrior cats oc#fleathistle#warrior cats original character#dark forest member#amaranthkit#fadingflea babies#anon#ask#i asked my friend and yes this is in fact them lol

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

An article about how yellow jackets aid certain plants in getting seeds dispersed. (Via an interesting thread on Twitter with mentions of several other kinds of insects involved in seed dispersal and what does this imply about how widespread it is.) What I think is particularly interesting in this abstract is the remark that no other animals than the wasps were seen visiting the seeds.

Carnivorous wasps of the family Vespidae are known to seek out and disperse the diaspores of at least two North American and two Asian plant species. Attraction of the wasps to the diaspores is likely due to the release of volatile compounds that signal availability of an eliaiosome rich in protein and fat, which the wasps remove before releasing the diaspore. It is thought that this interaction between carnivorous wasps and plants is rare, occurring in just a few plant species. Here, we present our findings on dispersal of spicebush (Calycanthus occidentalis Hook. & Arn.) achenes by carnivorous wasps of the genus Vespula. Observations and experiments were performed with the goals of discovering: how geographically widespread this interaction is; what the reward system is, if any; and, how wasps detect the achenes. Eight populations of C. occidentalis in northern California were used to observe wasps and plants, and to perform experiments on wasp attraction to the achenes. In all examined populations, workers of western yellowjacket (Vespula pensylvanica [de Saussure, 1857]) were observed entering mature Calycanthus receptacles, removing achenes, taking flight with them, and successfully transporting achenes through the air. Receptacles were found to open upward at an average angle of 45° (SD = 29°), preventing the achenes from falling to the ground when mature. No animals other than wasps were observed visiting the receptacles during the observations. Experiments suggest that wasps are attracted to an elaiosome-like organ of the achene. Nutritional analysis shows that this organ is high in fat and protein. Further experiments using solvent extracts of the achenes suggest that the attraction is likely mediated by volatile compounds.

15 notes

·

View notes