#melissa febos

Text

When it comes to sex scenes, the rules say things like: Don't write them at all, and if you do, don't use these words. Don't write them silly, porny, dramatic, tragic, pathological, grim, or ridiculous.

My whole practical thesis around the craft of writing a sex scene is this: it is exactly the same as any other scene. Our isolation of sex from other kinds of scenes is not indicative of sex’s difference, but the difference in our relationship to sex. It is our reluctance to name things, the shame we've been taught, our fraught compulsion to an act a theatre of types. It is indicative of the lack of imagination that centuries of patriarchy and white supremacy has wrought on us.

To teach sex scenes is to talk about plot, dialogue, pacing, description and characterisation: all those elements that make a captivating scene. A sex scene should advance the story and occur in a chain of causality that springs from your characters’ choices. It should employ sensory detail that concretises and also speaks symbolically to the deeper content of the story. Or if not, it should service your work of art in whatever ways you want from your scenes.

“Mind Fuck: Writing Better Sex” in Body Work by Melissa Febos

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

[“The problem is that we have exiled sex in our minds. We have isolated it from the larger inclusive narrative and we have limited its definition to that which serves the most privileged class of protagonists.

I think that this is a symptom of that other habit of treating whole classes of human beings as though their stories do not have the stakes, narrative depth, and complexity typically assigned to dominant protagonists. It is a craft quandary indeed to write yet another sex scene in which a white male protagonist exercises his archetypal masculinity on a secondary, two-dimensional character functioning as a prop in his hero’s journey without any narrative awareness of this exhausted trope.

But to write a sex scene in which that marginalized character is treated with some reverence and depth? To write it from their perspective? Or to write a scene in which a white male character experiences, even in an inchoate way, the deep discomfort that occurs when we act out our erotic story on another body without recognizing its humanity? I’ll repeat the unrule: you can use any words you want.

Here is Eileen Myles, from Inferno, in case you thought comparing a pussy to soup, or using the word crotch, was out of bounds or unsexy:

But after kissing her mouth a little chapped which seemed familiar then feeling her breasts not so large, but nice round and beautiful, familiar breasts, ones I already knew in some way I tugged down her pants. She said Oh. Like a soft amount of light, a small gust of wind. And luckily she had some sweatpants on or something, a stretchy waist. Easy getting them down and there were her lemony legs. Not big not strong, but smooth soft hair like peaches everything that way. Pink rose warm. I just dived down. It couldn’t have been too fast. Time was being so slow and warm. And there it was. A pussy, the singular place on a girl, it’s where I’m going. Wiggly thing, like soup, like a bowl. Another mouth. Like lips between her legs and the taste of it. Piss and fruit. I pressed my face against its bone and it moved. She was letting me. All this was happening. I smelled the future right there, a present and a past. All that went through her, known through the soft sweet flesh of her lips and clit. It was like my face felt loved temporarily […] I felt plunged into a tropical movie in which light was bathing my head and her pussy, her cunt, her crotch was a warm smile and for a moment I lived in her sun.

The revelation here is not that these words can be used in a sex scene, but that a pussy, a cunt, a crotch can be transformed by a sex scene. “Language is never innocent,” Roland Barthes once wrote, and I agree. Here, in the sense that the words pussy, cunt, and crotch all carry the connotative luggage of all their previous contexts—the violence, disgust, and pornographic theater of all the scenes and mouths I’ve heard them in and from. Experience, however, is innocent. This narrator’s sexual reality is so powerful a phenomenon that it washes these words of their previous connotations. Now they mean not a wimp or a bitch or the place on a woman that belongs to a man, but something magnificent and weird, pure and exotic, deeply familiar and erotic—a warm smile, a cosmic body. Just as sweatpants become perfect attire for such a scene, smooth soft hair like peaches, and the actual smell of sex a good one. When they enter this revelatory scene, these degraded words are suddenly imbued with the same reverence as their speaker. To use them is an incontrovertible act of (re)creation.”]

melissa febos, from body work: the radical power of personal narrative, 2022

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

I lost myself so long ago I don't even know how to start looking

on theater, hélène cixous // abandon me, melissa febos // i'm not angry anymore, paramore // @ojibwa // also @/ojibwa // the chronology of water, lydia yuknavitch // from the last motel before a decade's long purgatory, silas denver melvin ( @sweatermuppet ) // on theater, hélène cixous

#on grief#grief#love#anger#parallel#poetry#art#userojibwa#usersweatermuppet#silas denver melvin#paramore#im not angry anymore#helene cixous#melissa febos#lydia yuknavitch#web weaving#text weaving#parallels#500+#1000+#2000+

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

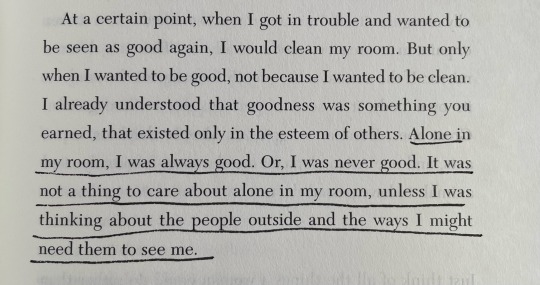

from the mirror test by melissa febos

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

When I first came to the city, it took all my fantasies and set them on fire, turned them into flickering constellations of light.

-- Melissa Febos

(Roma)

#lights#traffic lights#fire#fantasy#travel photography#melissa febos#Italy#Roma#Rome#quote#evening photography#dusk#fantasies

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

“i was a girl gulping a woman’s grief.”

— Call My Name, Melissa Febos

#call my name#melissa febos#bookblr#books & libraries#books and literature#books and reading#books#dark acadamia quotes#beautiful quote#academia#classic lit quotes#classic literature#heart wrenching#heartbreak#this is depressing#depressing shit#kinda depressing#tw depressing stuff#sorry for being depressing#depressing quotes#depressiv#sad qutoes#woman#tumblr girls

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

I became a writer because I loved writing and I still do. I became a writer because the process helped me survive and it still does.

— Melissa Febos, Body Work

#body work#melissa febos#quotes#literary quotes#literature#memoir#writing#books#spilled ink#thoughts#lit#pretty quotes#quote of the day#reverie#reverie quotes#quote#book quote#book quotes#inspiring quote#inspiring quotes#beautiful quote#beautiful quotes

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

"My ability to predict the ends of my relationships always had less to do with a single flaw that would break us and more with our failure to change before it did. That is the principal difference between my relationship with Donika and my relationship with past loves. Donika and I both know how to change, and we do. Sure, we’ve had about 30 years of therapy between us and a long track record of learning from our mistakes in love, but mostly we enjoy growing—the work and reward of it, the surprise at who we become when we try to become more ourselves. My inability to see our demise isn’t evidence that our relationship has no flaws, only that our ability to change is predictable, which means that the future never is. For the first time, I trust that whatever hardships we encounter, we will be able to grow around them."

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

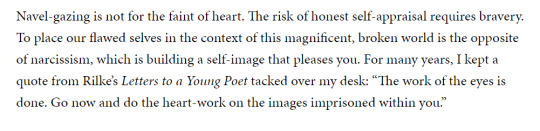

Melissa Febos, author of Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative (Catapult, 2022), in “The Heart-Work: Writing About Trauma as a Subversive Act.”

#Melissa Febos#Body Work#Heart Work#Trauma#Subversive#Writing#Quote#Inspiration#Writer's Block#Nonfiction#Memoir#Catapult

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

...While I sometimes resist the work of writing I resist my own psychic suffering more, and writing has become for me a primary means of digesting and integrating my experiences and thereby reducing the pains of living. Or if not, at least making them useful to myself and to others. There is no pain in my life that has not been given value by the alchemy of creative attention.

— Melissa Febos, Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative (Catapult, March 15, 2022)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hätte Foucault doch nur den erstaunlichen Einfluss von Social Media erleben können, ein wahrer Coup einer panoptischen Technik. Wir leben unser Leben in Dauerpose, posten am laufenden Band Beweise dafür, wie gut wir unseren Körper diszipliniert haben.

Melissa Febos: "Girlhood", S.234

#melissa febos#febos#girlhood#foucault#disziplinargesellschaft#kontrollgesellschaft#social media#körper#posten#kontrolle#panoptikum

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“In the 1980s, social psychologist James W. Pennebaker conducted some now-famous studies on his theory of expressive writing. Pennebaker instructed participants in his experimental group to write about a past trauma, expressing their very deepest thoughts and feelings surrounding it. In contrast, control participants were asked to write as objectively and factually as possible about neutral topics without revealing their emotions or opinions. For both groups, the schedule was fifteen minutes of continuous writing repeated over four consecutive days. Some of the participants in the experimental group found the exercise upsetting. All of them found it valuable and meaningful. Monitoring over the subsequent year revealed that those participants made significantly fewer visits to physicians. Pennebaker’s research has since been replicated numerous times and his results supported: Expressive writing about trauma strengthens the immune system, decreases obsessive thinking, and contributes to the overall health of the writers. And this is after only four days of fifteen-minute sessions.

Pennebaker has since written extensively about how this effect can also be consistent on a much larger scale, in communities who have suffered the atrocities of war and other political events. The articulation of painful memories, including the literature and art that arises out of political upheaval, is integral to the formation, preservation, and integration of collective memory. Let’s face it: if you write about your wounds, it is likely to be therapeutic. Of course, the writing done in those fifteen minutes was surely terrible by artistic standards. But it is a logical fallacy to conclude that any writing with therapeutic effect is terrible. You don’t have to be into therapy to be healed by writing. Being healed does not have to be your goal. But to oppose the very idea of it is nonsensical, unless you consider what such a bias reveals about our values as a culture. Knee-jerk bias backed by flimsy logic and pseudoscience has always been a preferred disguise of our national prejudices. That these topics of the body, the emotional interior, the domestic, the sexual, and the relational are all undervalued in intellectual literary terms, and are all associated with the female spheres of being, is not a coincidence. This bias against personal writing is often a sexist mechanism, founded on the false binary between the emotional (female) and the intellectual (male), and intended to subordinate the former.”]

melissa febos, from body work: the radical power of personal narrative, 2022

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thesmophoria, Melissa Febos

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just finished. It was the exact book I needed to read at this exact moment of writing my current project. Love when that happens. (It’s beautifully written, too.)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The problem is not that vagina is an unsexy word… The problem is that we have exiled sex in our minds. We have isolated it from the larger inclusive narrative and we have limited its definition to that which serves the most privileged class of protagonists.

If sex words have been overused, so have grief words. But you don't see folks so readily nixing the use of sad or tears or melancholy, or scenes of staring into the middle distance as you contemplate the terrifying sublimity of your own mortality. Not the way you see folks banning the words pussy, hump, thrust, or, most terrifyingly and supposedly unsexy, vagina.

-Melissa Febos, “Mind Fuck: Writing Better Sex” in Body Work

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The articulation of painful memories, including the literature and art that arises out of political upheaval, is integral to the formation, preservation, and integration of collective memory.

— Melissa Febos, Body Work

#body work#melissa febos#quotes#literary quotes#literature#memoir#writing#books#spilled ink#thoughts#lit#pretty quotes#quote of the day#reverie#reverie quotes#quote#book quote#book quotes#inspiring quote#inspiring quotes#beautiful quote#beautiful quotes

27 notes

·

View notes