#mark ewert

Text

Cineploit-Plattenvorstellung: Morlock und Pan/Scan

Cineploit-Plattenvorstellung: Morlock und Pan/Scan

Hypnotische Klangwelten und retro-futuristische Tonkunst. Willkommen bei einer weiteren Ausgabe des Kessel Buntes. Diesmal darf ich euch zwei Musikprojekte bzw. deren neuste Veröffentlichungen nahe bringen. Die Briten von Morlock legen ihre zweite Langrille “The Outcasts” nach und das Stuttgarter Projekt Pan/Scan liefert mit “A Far Distant Corner Of Nothing Special” die logische Fortsetzung zu…

View On WordPress

#Alasdair C. Mitchell#Andrew Prestidge#Chris Fullard#Christian Rezchak#Christian Rzechak#Christine Marks#Cineploit#Cosmic Soundscape#Lovecraft#Marc Ewert#Markus Steinhäuser#Matt Thompson#Maurice Bendrix#Misha Hering#Mondo Bizarr#Morlock#Musikreview#Pan/Scan#Plattenkritik#Psychedelic Rock#Retro#Roland Scriver#Sospetto#Space Rock#Synth#The Outsider#Zoltan

0 notes

Text

Speak of the Unspeakable: Memoirs of the Past

Germany’s literature legacy is an expansive one. From philosophy to fiction to verse poetry, Germans have made prolific contributions to humanity through their writing, something that has resulted in international recognition and, perhaps more importantly, a better understanding of the human condition. German literature is rich in beautifully crafted stories, especially from the eras of Sturm und Drang, Romanticism, and Realism. Certain German books are excellent introductions not only to German literature but to German culture and the history of Germany too.

In the modern post-war period, the characteristics of German literature were dominated by both subjective and political explorations of Nazism, the Holocaust, war, and political division; these themes were written about in an attempt to help heal the wounds of the 21st century. The most important aspects that have marked the development of German literature, characteristics that distinguish it and were decisive for its evolution over time, have to do with the importance that the avant-garde represents for its authors. In particular, for the modern classics, it is of great relevance in the development of literature and will give access to a series of writers who find in them access to literature.

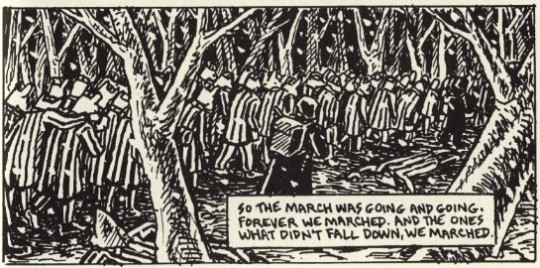

Maus' story depicted by the narrator wanted to work with anthropomorphism in a comic book, and decided to use cats and mice as the center of this particular comic. Logically, the decision that the animals are chosen would work well to illustrate his father's experience in the period just before and during the holocaust. The narrator wants to portray a larger specter of memory than a first-person verbal narrative can achieve. Spiegelman uses the form of the comic medium to visualize the connection of the mind between the present and the past. By including both Artie and Vladek, he has achieved a narration not only depicting one side of the story, but two very different sides. As we know, Artie is not a survivor of the physical Holocaust, but he is a survivor in his own way. Both father and son have had to deal with the psychological consequences and aftermath of the Holocaust.

In Requiem for a Nun, William Faulkner writes that "The past is never dead. It’s not even the past. " (1) It points out that the past never dies because humans have a way of adapting the past to suit their present needs. (2) This happens on a personal level, as well as on a political and collective level. The graphic novel’s characteristic way of demonstrating narrative levels and time makes this story excel as not only a narration of memory but also a narration on memory.

While numerous academic studies have done extensive work on the use of the animal metaphor and the complicated relationship between father and son, few have, according to Jeanne C. Ewe "focused on Maus as a visual narrative: its graphic arrangement of narrative layers and frames, its pictorial treatment of narrative time..." (Ewert 87). The animal metaphor is an act of focalization; it plays on the assumptions of the human race as not one, but divided into several. It makes the reader contemplate the idea of a natural hierarchy between "races". While cats are the natural predators and mice are the natural prey, Germans and Jews are of the same race; the human race. However, by depicting humans as different races, the absurdity of the Nazi doctrine is highlighted. We are not presented with the past and then the future, but rather a stacking, morphing, and collision of temporalities. This is much more suitable to explain human memory.

The graphic novel medium not only allows it to challenge traditional expectations and representations of time, narration, and focalization, but the medium itself has the possibility of reaching a large readership. Most likely, this could include people that otherwise might never have picked up a Holocaust narrative. Chute argues that this is the gift of the graphic novel, its possibility to write a history that combines "formal experimentation with an appeal to mass readership" (Chute, "Comics as Literature" 459).

Irrevocably, Maus is a reflection of challenges. The power struggle in defining the past is thus not unique to Maus, but is a widespread problem in our daily lives. It is an act of prosthetic memory. Maus’ importance to collective memory is not because of Landsberg’s idea of prosthetic memory, but rather that it works to involve the reader in the difficult process of both remembering and creating memory.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today’s disabled character of the day is Moki from the Calamity Adventure series, who has acrophobia

Requested by Anon

[Image Description: Photo of Mark Ewert playing Moki. He has short brown hair and brown eyes. He is wearing a blue button up shirt with yellow stripes and a white collar. To her right is his characters name written in red. He is smiling.]

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Espresso mit Meerblick in Heringsdorf Klaus bringt Kaffeegenuss aus Bella Italia an die Seebrücke nach Heringsdorf. Hier genießt man wunderbar cremigen Cappuccino, rassigen Espresso und allerlei andere Kaffeespezialitäten. Mit Klaus startet man in den Tag mit einer großen Portion “dolce vita” und echtem italienischen Genuss für unterwegs. Wer bist Du und was verbindet Dich mit Usedom? Ich bin Klaus Ewert, man kennt mich aber eigentlich nur unter Kaffeeklaus. Sogar die Kinder sprechen mich nicht mit Klaus, sondern mit Kaffeeklaus an. In der Kindheit und Jugend bin ich nur zum Baden auf die Insel gekommen, mittlerweile wohne und arbeite ich hier. Vor gut acht Jahren habe ich meinen Job gekündigt und mich ganz und gar dem braunen Gold, dem Kaffee verschrieben. Ich habe sozusagen mein Hobby zum Beruf gemacht, wie man so schön sagt. Meine kleine (mobile) Kaffee-Bar steht gegenüber des Eingangs zur Seebrücke in Heringsdorf, zwischen Rehaklinik und Kurhotel. Was genau macht deinen Kaffee so besonders? Man hört und liest in den sozialen Medien, es soll der beste Kaffee der Insel sein? Da gibt es viele Faktoren, die, wenn sie optimal aufeinander abgestimmt sind, einen guten Kaffee in die Tasse zaubern. Neben dem Wasser, der Maschine und der Mühle spielen die Bohnen die absulute Hauptrolle.

Für den Kaffee und die Kaffeespezialitäten habe ich eine eigene, markenrechtlich geschützte Kaffee-Marke, den Kaffeeklaus Espresso, zusammen mit einer Rösterei kreiert. Das ist eine ganz spezielle Mischung aus verschiedenen Rohbohnen. Die genaue Zusammensetzung bleibt natürlich mein Betriebsgeheimnis. Die Bohnen werden erst nach Auftrag von mir im speziellen Aeroröster für mich in einer kleinen Manufaktur geröstet. Die Qualität spielt dabei für mich und die Rösterei die wichtigste Rolle. Auch das ist eines meiner Geheimnisse. Den Rest des Interviews findet ihr auf unserer Website oder einfach den Link in der Bio klicken. (hier: Heringsdorf, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgqxCCgMO63/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

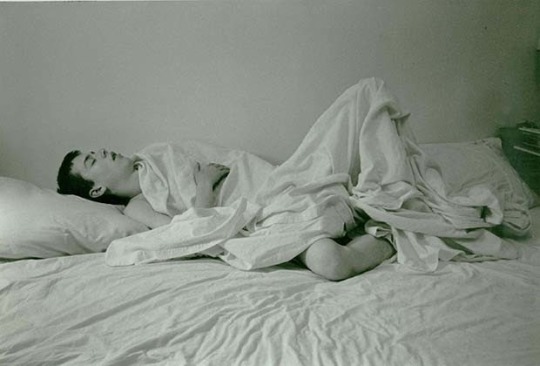

Marcus Ewert

by Allen Ginsberg

1 note

·

View note

Text

HERMENEUTICS-BY STEVE FINNELL

Hermeneutics is the science of interpretation of the Scriptures. Isolating verses of Scripture to prove a point of doctrine is common practice, but is it a valid scientific approach to understanding God's word?

Let us examine this approach when dealing with the question, "WHAT MUST I DO TO BE SAVED?"

John 3:16 For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life.

Is that verse true? Yes, but does it include all the requirements for salvation? No, it does not.

Mark 16:16 He who has believed and been baptized shall be saved; but he who has disbelieved shall be condemned.

Is that verse true? Yes, but does it include all the requirements for salvation?

Romans 10:9 that if you confess with your mouth Jesus as Lord, and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, you will be saved.

Yes, that verse is true; but does include all the requirements for salvation?

John 3:5 Jesus answered, Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit he cannot enter into the kingdom of of God.

Is that verse true? Yes, but it does not explain the process to be born of water and the Spirit.

Ephesians 2:8 For by grace you have been saved through faith; and that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God;

Is that verse true? Yes, we have the opportunity for salvation because of God's grace, however, that verse does not say that we are saved by grace alone nor does it say we are saved by faith only.

Romans 6:4-5 Therefore we have been buried with Him through baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in the newness of life. 5 For if we have become united with Him in the likeness of His death, certainly we shall also be in the likeness of His resurrection,

Is that verse true? Yes, but baptism alone is not the only requirement in order to walk in newness of life.

1 Peter 3:21 Corresponding to that, baptism now saves you---not the removal of dirt from the flesh, but an appeal to God for a good conscience---through the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Is it true that water baptism saves us? Yes, but that verse does not say baptism alone saves us.

Acts 22:16 Now why do you delay? Get up and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on His name!

Is that verse true? Yes, but does it list all the requirements for salvation?

Galatians 3:27 For all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ.

Is that verse true? Yes, but only if faith precedes baptism.

Acts 2:38 Peter said to them, "Repent, and each of you baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Is that verse true? Yes, but it does not mean that you can have your sins forgiven without having faith and confessing Jesus as Lord and Savior.

Acts 16:30-31..."Sirs what must I do to be saved?" 31 They said, "Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved, you and your household."

Is that verse true? Yes, however, it does not state that men are saved by "faith only."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Bible says we saved by grace. It does not state we are saved by grace alone.

The Bible says we we are saved by believing in Jesus. It does not say we are saved by faith only.

The Bible says we are saved by confessing Jesus as Lord and believing that God raised Him from the dead. It does not say that by confessing Him and believing in His resurrection alone that we will be saved.

The Bible does says we must repent in order to have our sins forgiven. The Bible does not say repentance alone saves us.

The Bible teaches us that water baptism is for the forgiveness of sins and that it saves us. It does not say baptism alone saves us.

WE ARE SAVED BY?

We are saved by grace.

We are saved by faith.

We are saved by repentance.

We are saved by confession.

We are saved by water baptism.

WHICH REQUIREMENT OF GOD'S PLAN FOR OUR SALVATION CAN WE ELIMINATE AND STILL BE SAVED?

The jailer and his household believed and were baptized that very hour. (Acts 16:30-33) There was no law keeping nor good deeds required for them to be saved.

SAVED BY WORKS? - BY STEVE FINNELL

Are we saved from the penalty of sin by works. No, we are not saved by works. When the apostle Paul tells us we not saved by works, what does he mean? Does he mean that we do not have to believe in Jesus? No, he does not. Is Paul saying that being immersed in water is a work of the law of Moses? No, he is not. Is Paul saying that confessing Jesus as Lord and Christ is a work of the law of Moses? No, he is not. Is Paul teaching that men do not need to acknowledge that God raised Jesus from the grave because that would be a work of the law of Moses? No, he is not.

Ephesians 2:8-9 For by grace you have been saved through faith, and that not of yourselves, it is a gift of God, 9 not of works, lest anyone should boast. (NKJV)

The apostle Paul is saying men are not saved by works of the law of Moses.

Galatians 2:16 "know that a man is not justified by the works of the law but by faith in Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Christ Jesus, that we might be justified by faith in Christ and not by the works of the law; for by the works of the law no flesh shall be justified. (NKJV)

You cannot be justified by works of the law of Moses.

Acts 13:39 "and by Him everyone who believes is justified from all things from which you could not be justified by the law of Moses. (NKJV)

The works of the law of Moses do not save anyone.

Mark 16:16 "He who believe and is baptized will be saved...(NKJV)

Believing and being immersed in water are not works of the law of Moses.

Acts 22:16 'And now why are you waiting? Arise and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on the name of the Lord.'(NKJV)

Saul did not have his sins wash by keeping the law of Moses. Baptism and calling on the name of the Lord are not part of the law of Moses.

Acts 2:38 Then Peter said to them, "Repent, and let every one of you be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.(NKJV)

Making the commitment to turn from sin and turn toward God and being baptized in water is not part of the law of Moses. Repentance and baptism are not works of the law of Moses.

John 6:29 Jesus answered and said to them, "This is the work of God, that you believe in Him whom He sent." (NKJV)

Believing in Jesus is a work, however, it is not a work of the law of Moses.

Colossians 2:12-13 buried with Him in baptism, in which you were raised with Him through faith in the working of God, who raised Him from the dead. 13 And you being dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, He has made alive together with Him, having forgiven you all trespasses,(NKJV)

Being buried with Christ in baptism is not a law of Moses. Men are not forgiven of trespasses because they keep the law of Moses.

When Jesus said believe and be baptized and you will be saved, He was not quoting the works of law of Moses.

Is Mark 16:9-20 Inspired?by

Dave Miller, Ph.D.

The science of textual criticism is a field of inquiry that has been invaluable to ascertaining the original state of the New Testament text. Textual criticism involves “the ascertainment of the true form of a literary work, as originally composed and written down by its author” (Kenyon, 1951, p. 1). The fact that the original autographs of the New Testament do not exist (Comfort, 1990, p. 4), and that only copies of copies of copies of the original documents have survived, has led some falsely to conclude that the original reading of the New Testament documents cannot be determined. For example, Mormons frequently attempt to establish the superiority of the Book of Mormon over the Bible by insisting that the Bible has been corrupted through the centuries in the process of translation (a contention shared with Islam in its attempt to explain the Bible’s frequent contradiction of the Quran). However, a venture into the fascinating world of textual criticism dispels this premature and uninformed conclusion.The task of textual critics, those who study the extant manuscript evidence that attests to the text of the New Testament, is to examine textual variants (i.e., divergencies among the manuscripts) in an effort to reconstruct the original reading of the text. They work with a large body of manuscript evidence, the amount of which is far greater than that available for any ancient classical author (Ewert, 1983, p. 139; Kenyon, 1951, p. 5; Westcott and Hort, 1964, p. 565). [NOTE: The present number of Greek manuscripts—whole and partial—that attest to the New Testament stands at an unprecedented 5,748 (Welte, 2005)].In one sense, their work has been unnecessary, since the vast majority of textual variants involve minor matters that do not affect doctrine as it relates to one’s salvation. Even those variants that might be deemed doctrinally significant pertain to matters that are treated elsewhere in the Bible where the question of genuineness is unobscured. No feature of Christian doctrine is at stake. Variant readings in existing manuscripts do not alter any basic teaching of the New Testament. Nevertheless, textual critics have been successful in demonstrating that currently circulating New Testaments do not differ substantially from the original. When all of the textual evidence is considered, the vast majority of discordant readings have been resolved (e.g., Metzger, 1978, p. 185). One is brought to the firm conviction that we have in our possession the New Testament as God intended.The world’s foremost textual critics have confirmed this conclusion. Sir Frederic Kenyon, longtime director and principal librarian at the British Museum, whose scholarship and expertise to make pronouncements on textual criticism was second to none, stated: “Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established” (Kenyon, 1940, p. 288). The late F.F. Bruce, longtime Rylands Professor of Biblical Criticism at the University of Manchester, England, remarked: “The variant readings about which any doubt remains among textual critics of the New Testament affect no material question of historic fact or of Christian faith and practice” (1960, pp. 19-20). J.W. McGarvey, declared by the London Times to be “the ripest Bible scholar on earth” (Phillips, 1975, p. 184; Brigance, 1870, p. 4), conjoined: “All the authority and value possessed by these books when they were first written belong to them still” (1956, p. 17). And the eminent textual critics Westcott and Hort put the entire matter into perspective when they said:

Since textual criticism has various readings for its subject, and the discrimination of genuine readings from corruptions for its aim, discussions on textual criticism almost inevitably obscure the simple fact that variations are but secondary incidents of a fundamentally single and identical text. In the New Testament in particular it is difficult to escape an exaggerated impression as to the proportion which the words subject to variation bear to the whole text, and also, in most cases, as to their intrinsic importance. It is not superfluous therefore to state explicitly that the great bulk of the words of the New Testament stand out above all discriminative processes of criticism, because they are free fromvariation, and need only to be transcribed (1964, p. 564, emp. added).

Writing in the late nineteenth century, and noting that the experience of two centuries of investigation and discussion had been achieved, these scholars concluded: “[T]he words in our opinion still subject to doubt can hardly amount to more than a thousandth part of the whole of the New Testament” (p. 565, emp. added).

THE AUTHENTICITY OF MARK 16:9-20

One textual variant that has received considerable attention from the textual critic concerns the last twelve verses of Mark. Much has been written on the subject in the last two centuries or so. Most, if not all, scholars who have examined the subject concede that the truths presented in the verses are historically authentic—even if they reject the genuineness of the verses as being originally part of Mark’s account. The verses contain no teaching of significance that is not taught elsewhere. Christ’s post-resurrection appearance to Mary is verified elsewhere (Luke 8:2; John 20:1-18), as is His appearance to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:35), and His appearance to the eleven apostles (Luke 24:36-43; John 20:19-23). The “Great Commission” is presented by two of the other three gospel writers (Matthew 28:18-20; Luke 24:46-48), and Luke verifies the ascension twice (Luke 24:51; Acts 1:9). The promise of the signs that were to accompany the apostles’ activities is hinted at by Matthew (28:20), noted by the Hebrews writer (2:3-4), explained in greater detail by John (chapters 14-16; cf. 14:12), and demonstrated by the events of the book of Acts (see McGarvey, 1875, pp. 377-378).Those who reject the originality of the passage in Mark, while acknowledging the authenticity of the events reported, generally assign a very early date for the origin of the verses. For example, writing in 1844, Alford, who forthrightly rejected the genuineness of the passage, nevertheless conceded: “The inference therefore seems to me to be, that it is an authentic fragment, placed as a completion of the Gospel in very early times: by whom written, must of course remain wholly uncertain; but coming to us with very weighty sanction, and having strong claims on our reception and reverence” (1:438, italics in orig., emp. added). Attributing the verses to a disciple of Jesus named Aristion, Sir Frederic Kenyon nevertheless believed that “we can accept the passage as true and authentic narrative, though not an original portion of St. Mark’s Gospel” (1951, p. 174, emp. added). More recently, textual scholars of no less stature than Kurt and Barbara Aland, though also rejecting the originality of the block of twelve verses in question, nevertheless admit that the longer ending “was recognized as canonical” and that it “may well be from the beginning of the second century” (Aland and Aland, 1987, pp. 69,227). This admission is remarkable since it lends further weight to the recognized antiquity of the verses—what New Testament textual critic Bruce Metzger, professor Emeritus of New Testament Language and Literature at Princeton Theological Seminary, referred to as “the evident antiquity of the longer ending and its importance in the textual tradition of the Gospel” (1994, p. 105)—placing them in such close proximity to the original writing of Mark so as to make the gap between them virtually indistinguishable.

THE GENUINENESS OF MARK 16:9-20: THE TEXTUAL EVIDENCE

In light of these preliminary observations regarding authenticity, what may be said regarding the genuineness of the last twelve verses of the book of Mark? In arriving at their conclusions, textual critics evaluate the evidence for and against a reading in terms of two broad categories: external evidence and internal evidence (see Metzger, 1978, pp. 209ff.). External evidence consists of the date, geographical distribution, and genealogical interrelationship of manuscript copies that contain or omit the passage in question. Internal evidence involves both transcriptional and intrinsic probabilities. Transcriptional probabilities include such principles as (1) generally the shorter reading is more likely to be the original, (2) the more difficult (to the scribe) reading is to be preferred, and (3) the reading that stands in verbal dissidence with the other is preferable. Intrinsic probabilities pertain to what the original author was more likely to have written, based on his writing style, vocabulary, immediate context, and his usage elsewhere.Four Textual PossibilitiesAccording to Metzger (1994, pp. 102ff.), the extant manuscript evidence contains essentially four different endings for the book of Mark: (1) the omission of 16:9-20; (2) the inclusion of 16:9-20; (3) the inclusion of 16:9-20 with the insertion of an additional statement between verse 8 and verse 9 that reads: “But they reported briefly to Peter and those with him all that they had been told. And after this Jesus himself sent out by means of them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation”; and (4) the inclusion of 16:9-20 with the insertion of an additional statement between verses 14 and 15 which reads:

And they excused themselves, saying, “This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits [or, does not allow what lies under the unclean spirits to understand the truth and power of God]. Therefore reveal thy righteousness now”—thus they spoke to Christ. And Christ replied to them, “The term of years of Satan’s power has been fulfilled, but other terrible things draw near. And for those who have sinned I was delivered over to death, that they may return to the truth and sin no more, in order that they may inherit the spiritual and incorruptible glory of righteousness which is in heaven.”

The fourth reading of the text may be eliminated as spurious. Meager external evidence exists to support it, i.e., only one Greek manuscript—Codex Washingtonianus. As Jack Lewis noted: “The support for the shorter ending is so inferior that no scholar would champion that Mark wrote this ending” (1988, p. 598). It bears what Metzger called “an unmistakable apocryphal flavor” (1994, p. 104). The statement does not match the style and grandeur of the rest of the section, leaving the general impression of having been fabricated. This latter point applies equally to the third ending since it, too, possesses a rhetorical tone that contrasts—even clashes—with Mark’s simple style.The third ending represents a classic case of conflation—incorporating both verses 9-20 as well as the shorter ending—and may also be eliminated from consideration. In addition to internal evidence, the external evidence is insufficient to establish its genuineness. It is supported by four uncials (019, 044, 099, 0112) that date from the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries, one Old Latin manuscript (which omits verses 9-20), a marginal notation in the Harclean Syriac, several Coptic (Sahidic and Bohairic) manuscripts (see Kahle, 1951, pp. 49-57), and several late Ethiopic manuscripts (see Sanday, 1889, p. 195, and Metzger’s response, 1972). Besides being discredited for conflation, the third ending lacks sufficient internal and external evidence to establish its genuineness as having been originally written by Mark.OmissionUltimately, therefore, the question is reduced simply to whether verses 9-20 are to beincluded or excluded as genuine. Over the last century and a half, scholars have come down on both sides of the issue. Those who have questioned the genuineness of the verses have included F.J.A. Hort (Westcott and Hort, 1882, pp. 29-51), B.H. Streeter (1924, pp. 333-360), J.K. Elliott (1971, pp. 255-262), and Bruce Metzger (1994, pp. 102-106). On the other hand, those who have insisted that Mark wrote the verses have included John W. Burgon (1871), F.H.A. Scrivener (1883, pp. 583-590), George Salmon (1889, pp. 156-164), James Morison (1892, pp. 446-449), Samuel Zwemer (1975, pp. 159-174), and R.C.H. Lenski (1945, pp. 748-775).The reading of the text that omits verses 9-20 altogether does, indeed, possess some respectable support (see the UBS Greek text’s critical apparatus—Aland, et al., 1983, p. 189). The weightiest external evidence is the omission of the verses by the formidable Greek uncials, the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, which date from the fourth century. These two manuscripts carry great persuasive weight with most textual scholars, resulting in marginal notations in many English translations. For example, the American Standard Version footnote to the verse reads: “The two oldest Greek manuscripts, and some other authorities, omit from verse 9 to the end. Some other authorities have a different ending to the Gospel.” The New International Version gives the following footnote: “The two most reliable early manuscripts do not have Mark 16:9-20.” Such marginal notations, however, fail to convey to the reader the larger picture that the external evidence provides, including additional Greek manuscript evidence, to say nothing of the ancient versions and patristic citations.Additional evidence for omission includes the absence of the verses from various versions: (1) the Sinaitic Syriac manuscript, (2) about one hundred Armenian manuscripts (see Colwell, 1937, pp. 369-386), and (3) the two oldest Georgian manuscripts that are dated A.D. 897 and 913. [NOTE: Many scholars list the Old Latin codex Bobiensis from the fourth/fifth century as evidence for the omission of the verses. However, as indicated by the critical apparatus of the UBS Greek text (see Aland, et al., 1983, p. 189), Bobiensis (k) contains the “short ending”—deemed by everyone to be spurious. Its scribe could have been manifesting his concern that something (i.e., verses 9-20) was missing and so settled for the “short ending”.]Among the patristic writers (i.e., the so-called “Church Fathers”), neither Clement of Alexandria (A.D. 215) nor Origen (A.D. 254) shows any knowledge of the existence of the verses. [Of course, simply showing no knowledge is no proof for omission. If we were to discount as genuine every New Testament verse that a particular patristic writer failed to reference, we would eventually dismiss the entire New Testament as spurious. Though virtually the entire New Testament is quoted or alluded to by the corpus of patristic writers (Metzger, 1978, p. 86)—no one writer refers to every verse.]Eusebius of Caesarea (A.D. 339), as well as Jerome (A.D. 420), are said to have indicated the absence of the verses from almost all Greek manuscripts known to them. However, it should be noted that the statement made by Eusebius occurs in a context in which he was offering two possible solutions to an alleged contradiction (between Matthew 28:1 and Mark 16:9) posed by a Marinus. One of the solutions would be to dismiss Mark’s words on the grounds that it is not contained in all texts. But Eusebius does not claim to share this solution. The second solution he offers entails retaining Mark 16:9 as genuine. The fact that he couches the first solution in the third person (i.e., “This, then, is what a person will say...”), and then proceeds to offer a second solution, when he could have simply dismissed the alleged contradiction on the grounds that manuscript evidence was decisively against the genuineness of the verses, argues for Eusebius’ own approval. The mere fact that the alleged contradiction was raised in the first place demonstrates recognition of the existence of the verses.Jerome’s alleged opposition to the verses is even more tenuous. He merely translated the same interchange between Eusebius and Marinus from Greek into Latin, recasting it as a response to the same question that he placed in the mouth of a Hedibia from Gaul (see the discussion by Burgon, 1871, p. 134). He most certainly was not giving his own opinion regarding the genuineness of Mark 16:9-20, since that opinion is made apparent by the fact that Jerome included the verses in his landmark revision of the Old Latin translations, the Vulgate, while excluding others that lacked sufficient manuscript verification. Jerome’s own opinion is further evident from the fact that he quoted approvingly from the section (e.g., vs. 14 in Against the Pelagians, II.15 [Schaff and Wace, 1954, 6:468]).Further evidence for omission of the verses is claimed from the Eusebian Canons, produced by Ammonius, which allegedly originally made no provision for numbering sections of the text after verse 8. Yet, again, on closer examination, of 151 Greek Evangelia codices, 114 sectionalize (and thus make allowance for) the last twelve verses (see Burgon, p. 391; cf. Scrivener, 1883).In addition to these items of evidence that support omission of verses 9-20, several manuscripts that actually do contain them, nevertheless have scribal notations questioning their originality. Some of the manuscripts have markings—asterisks or obeli—that ordinarily signal the scribe’s suspicion of the presence of a spurious addition. However, even here, such markings (e.g., tl, tel, or telos) can be misconstrued to mean the end of the book, whereas the copyist merely intended to indicate the end of a liturgical section of the lectionary. Metzger agrees that such ecclesiastical lection signs constitute “a clear implication that the manuscript originally continued with additional material from Mark” (1994, p. 102, note 1).The internal evidence that calls verses 9-20 into question resolves itself into essentially two central contentions: (1) the vocabulary and style of the verses are deemed non-Markan, and (2) the connection between verse 8 and verses 9-20 seems awkward and gives the surface appearance of having been added by someone other than Mark. These two contentions will be treated momentarily.InclusionStanding in contrast with the evidence for omission is the external and internal evidence for the inclusion of verses 9-20. The verses are, in fact, present in the vast number of witnesses (see the UBS Greek text’s critical apparatus—Aland, et al., 1983, p. 189). This point alone is insufficient to demonstrate the genuineness of a passage, since manuscripts may perpetuate an erroneous reading that crept into the text and then happened to survive in greater numbers than those manuscripts that preserved the original reading. Nevertheless, the sheer magnitude of the witnesses that support verses 9-20 cannot be summarily dismissed out of hand. Though rejecting the genuineness of the verses, the Alands offer the following concession that ought to give one pause: “It is true that the longer ending of Mark 16:9-20 is found in 99 percent of the Greek manuscripts as well as the rest of the tradition, enjoying over a period of centuries practically an official ecclesiastical sanction as a genuine part of the gospel of Mark” (1987, p. 287, emp. added). Such longstanding and widespread acceptance cannot be treated lightly nor dismissed easily. It is, at least, possiblethat the prevalence of manuscript support for the verses is due to their genuineness.The Greek manuscript evidence that verifies the verses is distinguished, not just in quantity, but also in complexion and diversity. It includes a host of uncials and minuscules. The uncials include Codex Alexandrinus (02) and Ephraemi Rescriptus (04) from the fifth century. [NOTE: Technically, the Washington manuscript may be combined with these two manuscripts as additional fifth-century evidence for inclusion of the verses, since it simply inserts an additional statement in between verses 14 and 15.] Additional support for the verses comes from Bezae Cantabrigiensis (05) from the sixth century (or, according to the Alands, the fifth century—1987, p. 107), as well as 017, 033, 037, 038, and 041 from the ninth and tenth centuries. The minuscule manuscript evidence consists of the “Family 13” collection, entailing no fewer than ten manuscripts, as well as numerous other minuscules. The passage is likewise found in several lectionaries.The patristic writings that indicate acceptance of the verses as genuine are remarkably extensive. From the second century, Irenaeus, who died c. A.D. 202, alludes to the verses in both Greek and Latin. His precise words in his Against Heresies were: “Also, towards the conclusion of his Gospel, Mark says: ‘So then, after the Lord Jesus had spoken to them, He was received up into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of God” (3.10.5; Roberts and Donaldson, 1973, 1:426). It is very likely that Justin Martyr was aware of the verses in the middle of the second century. At any rate, his disciple, Tatian, included the verses in his Greek Diatessaron (having come down to us in Arabic, Italian, and Old Dutch editions) c. A.D.170.Third century witnesses include Tertullian, who died after A.D. 220, in his On the Resurrection of the Flesh (ch. 51; Roberts and Donaldson, 1973, 3:584), Against Praxeas (ch. 30; Roberts and Donaldson, 3:627), and A Treatise on the Soul (ch. 25; Roberts and Donaldson, 3:206). Cyprian, who died A.D. 258, alluded to verses 17-18 in his The Seventh Council of Carthage(Roberts and Donaldson, 1971, 5:569). Additional third century verification is seen in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. Verses 15-18 in Greek and verses 15-19 in Latin are quoted in Part I: The Acts of Pilate (ch. 14), and verse 16 in its Greek form is quoted in Part II: The Descent of Christ into Hell (ch. 2) (Roberts and Donaldson, 1970, 8:422,436,444-445). De Rebaptismate (A.D. 258) is also a witness to the verses. All seven of these second and third century witnesses precede the earliest existing Greek manuscripts that verify the genuineness of the verses. More to the point, they predate both Vaticanus and Sinaiticus.Fourth century witnesses to the existence of the verses include Aphraates (writing in A.D.337—see Schaff and Wace, 1969, 13:153), with his citation of Mark 16:16-18 in “Of Faith” in his Demonstrations (1.17; Schaff and Wace, 13:351), in addition to the Apostolic Constitutions(5.3.14; 6.3.15; 8.1.1)—written no later than A.D. 380 (Roberts and Donaldson, 1970, 7:445,457,479). Ambrose, who died A.D. 397, quoted from the section in his On the Holy Spirit (2.13.145,151), On the Christian Faith (1.14.86 and 3.4.31), and Concerning Repentance(1.8.35; Schaff and Wace, 10:133,134,216,247,335). Didymus, who died A.D. 398, is also a witness to the genuineness of the verses (Aland, et al., 1983, p. 189), as is perhaps Asterius after 341.Patristic writers from the fifth century that authenticate the verses include Jerome, noted above, who died A.D. 420, Leo (who died A.D. 461) in his Letters (9.2 and 120.2; Schaff and Wace, 1969, 12:8,88), and Chrysostom (who died A.D. 407) in his Homilies on First Corinthians(38.5; Schaff, 1969, 12:229). Additional witnesses include Severian (after 408), Marcus-Eremita (after 430), Nestorius (after 451), and Augustine (after 455). These witnesses to the genuineness of Mark 16:9-20 from patristic writers is exceptional.The evidence for inclusion that comes from the ancient versions is also diverse and weighty—entailing a wide spectrum of versions and geographical locations. Several Old Latin/Itala manuscripts contain it. Though Jerome repeated the view that the verses were absent in some Greek manuscripts—a circumstance used by those who support exclusion—he actually included them in his fourth century Latin Vulgate (and, as noted above, quoted verse 14 in his own writings). The verses are found in the Old Syriac (Curetonian) as well as the Peshitta and later Syriac (Palestinian and Harclean). The Coptic versions that have it are the Sahidic, Bohairic, and Fayyumic, ranging from the third to the sixth centuries. The Gothic version (fourth century) has verses 9-11. The verses are also found in the Armenian, Georgian, and Old Church Slavonic versions.What must the unbiased observer conclude from these details? All told, the cumulativeexternal evidence that documents the genuineness of verses 9-20, from Greek manuscripts, patristic citations, and ancient versions, is expansive, ancient, diversified, and unsurpassed.Reconciling the EvidenceHow may the conflicting evidence for and against inclusion of the verses be reconciled? In the final analysis, according to those who favor omission of the verses, the two strongest, most persuasive pieces of evidence for their position are (1) the external evidence of the exclusion of the verses from the prestigious Vaticanus and Sinaiticus manuscripts, and (2) the internal evidence of the presence of multiple non-Markan words. The fact is that the presumed strength of these two factors has led many scholars to minimize the array of evidence that otherwise would be seen to support the verses—evidence that, as shown above, is vast and diversified in geographical distribution and age. If these two factors are demonstrated by definitive rebuttal to be inadequate, the evidence for inclusion will then be recognized as manifestly superior to that which is believed to support exclusion. What, then, may be said concerning the two strongest pieces of evidence that have led many scholars to exclude Mark 16:9-20 as genuine?Vaticanus and SinaiticusRegarding the first factor, it is surely significant that though Vaticanus and Sinaiticus omit the passage, Alexandrinus includes it. Alexandrinus rivals Vaticanus and Sinaiticus in both accuracy and age—removed probably by no more than fifty years. Why should the reading of two of the “Big Three” uncial manuscripts take precedence over the reading of the third? Are proponents staking their case in this regard on mere numerical superiority, i.e., two against one? Surely not, given the fact that the same scholars would insist that original readings are not to be decided by counting numbers of manuscripts. If sheer numbers of manuscripts decide genuineness, then Mark 16:9-20 must be accepted as genuine. Vaticanus and Sinaiticus should carry no more weight over Alexandrinus than that assigned by critics to the manuscripts that support inclusion on account of their superior numbers.Vaticanus is technically, at best, a half-hearted witness to the omission of the verses. Though he considered the verses as spurious, Alford nevertheless offered an observation that ought to give one pause: “After the subscription in B [Vaticanus—DM] the remaining greater portion of the column and the whole of the next to the end of the page are left vacant. There is no other instance of this in the whole N.T. portion of the MS[manuscript—DM], the next book in every other instance beginning on the next column” (p. 484, emp. added). This unusual divergence from the scribe’s usual practice suggests that he knew that additional verses were missing. The blank space he left provides ample room for the additional twelve verses.Interestingly, some have questioned the judgment of the scribe of Sinaiticus in his omission of Mark 16:9-20 on the grounds that he included the apocryphal books of the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas (Aland and Aland, 1987, p. 107). Likewise, the scribe of Vaticanus included several of the Apocrypha in the Old Testament, as Sir Frederic Kenyon observed, “being inserted among the canonical books in B [Vaticanus—DM] without distinction” (1951, p. 81, emp. added).Those who support exclusion of Mark 16:9-20 have not been forthright in divulging that, as a matter of fact, Vaticanus and Sinaiticus frequently diverge from each other, with one or the other siding with Alexandrinus against the other. For example, the allusions by Luke to an angel strengthening Jesus in the Garden and the “great drops of blood” (Luke 22:43-44) areomitted by Vaticanus and Alexandrinus, but Sinaiticus (the original hand) contains these verses (Metzger, 1975, p. 177). Luke’s report of Jesus’ statement on the cross (“Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do”—Luke 23:34), is included by Alexandrinus and Sinaiticus (the original hand), but omitted by Vaticanus (p. 180). On the other hand, Vaticanus sides with Alexandrinus against Sinaiticus in their inclusion of the blind man’s confession and worship of Jesus (“‘Lord, I believe!’ And he worshipped Him”) in John 9:38 (Metzger, p. 195). It is also the case that both Vaticanus and Sinaiticus are sometimes separately defective in their handling of a reading. For example, in John 2:3, instead of reading “they ran out of wine,” the original hand of Sinaiticus reads, “They had no wine, because the wine of the wedding feast had been used up”—a reading that occurs only in Sinaiticus and in no other Greek manuscript. Many other instances of dissimilarities and dissonance between Vaticanus and Sinaiticus could be cited that weaken the premature assessment of the strength of their combined witness against Mark 16:9-20. [Cf. Luke 10:41-42; 11:14; Acts 2:43,44; Romans 4:1; 5:2,17; 1 Corinthians 12:9; 1 John 4:19.] Further, in some cases the UBS committee rejected as spurious the readings of bothVaticanus and Sinaiticus, and instead accepted the reading of Alexandrinus (e.g., Romans 8:2—“me” vs. “you”; Romans 8:35—“the love of Christ” vs. “the love of God” [Sinaiticus] or “the love of God in Christ Jesus” [Vaticanus]).

SUMMARY OF EXTERNAL EVIDENCE

The following chart provides a visual summary of the external evidence for and against inclusion of Mark 16:9-20 for the first six centuries—since thereafter the manuscript evidence in favor of the verses increases even further (adapted and enhanced from Warren, 1953, p. 104). Observe that when one examines all three sources from which the text of the New Testament may be ascertained, the external evidence for the genuineness of the verses is considerable and convincing.

Non-markan styleThe second most persuasive piece of evidence that prompts some to discount Mark 16:9-20 as genuine is the internal evidence. Though the Alands conceded that the “longer Marcan ending” actually “reads an absolutely convincing text” (1987, p. 287), in fact, the internal evidence weighs more heavily than the external evidence in the minds of many of those who support omission of the verses. Observe carefully the following definitive pronouncement of this viewpoint—a pronouncement that simultaneously concedes the strength of the external evidence in favor of the verses:

On the other hand, the section is no casual or unauthorised [sic] addition to the Gospel. From the second century onwards, in nearly all manuscripts, versions, and other authorities, it forms an integral part of the Gospel, and it can be shown to have existed, if not in the apostolic, at least in the sub-apostolic age. A certain amount of evidence against it there is (though very little can be shown to be independent of Eusebius the Church historian, 265-340A.D.), but certainly not enough to justify its rejection, were it not that internal evidence clearly demonstrates that it cannot have proceeded from the hand of St. Mark (Dummelow, 1927, p. 73, emp. added).

Listen also to an otherwise conservative scholar express the same sentiment: “If these deductions are correct the mass of MSS [manuscripts—DM] containing the longer ending must have been due to the acceptance of this ending as the most preferable. But internal evidence combines with textual evidence to raise suspicions regarding this ending” (Guthrie, 1970, p. 77, emp. added). Alford took the same position: “The internalevidence...will be found to preponderate vastly against the authorship of Mark” (1844, 1:434, emp. added). Even Bruce Metzger admitted: “The long ending, though present in a varietyof witnesses, some of them ancient, must also be judged by internal evidence to be secondary” (1978, p. 227, emp. added). In fact, to Metzger, while the external evidence against the verses is merely “good,” the internal evidence against them is “strong” (1994, p. 105).So, in the minds of not a few scholars, if it were not for the internal evidence, the external evidence would be sufficient to establish the genuineness of the verses. What precisely, pray tell, is this internal evidence that is so powerful and weighs so heavily on the issue as to prod scholars to “jump through hoops” in an effort to discredit the verses? What formidable data exists that could possibly prompt so many to discount all evidence to the contrary? Let us see.Textual scholar Bruce Metzger summarized the internal evidence against the verses in terms of two factors: (1) the vocabulary and style of verses 9-20 are deemed non-Markan, and (2) the connection between verse 8 and verses 9-20 is awkward, appearing to have been “added by someone who knew a form of Mark that ended abruptly with verse 8 and who wished to supply a more appropriate conclusion” (1994, p. 105).

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN

VERSE 8 AND VERSES 9-20

Concerning the latter point, one must admit that the evaluation is highly subjective and actually nothing more than a matter of opinion. How is one to decide that a piece of writing is “awkward” or “likely” to have been added by someone other than Mark? Tangibleobjective criteria must be brought forward to support such a contention if its credibility is to be substantiated. As support for the contention, Metzger notes (1) that the subject of verse 8 is the women, whereas Jesus is the subject in verse 9, (2) that Mary Magdalene is identified in verse 9 even though she has been mentioned only a few lines before in 15:47 and 16:1, (3) the other women mentioned in verses 1-8 are now forgotten, and (4) the use of anastas de and the position of proton in verse 9 are appropriate at the beginning of a comprehensive narrative, but are ill-suited in a continuation of verses 1-8 (1994, p. 105). Let us examine briefly each of these four contentions.Regarding the first point, a simple reading of the verses does not demonstrate a shift in subject from the women to Jesus. In actuality, the subject has been Jesus all along, but more specifically, His resurrection appearances. After pausing to relate specific details of the tomb incident involving three women (vss. 2-8), the writer returns in verse 9 to the subject introduced in verse 1—an enumeration of additional resurrection appearances, reiterating Mary Magdalene’s name for the reason that He appeared to her “first.”Second, much is made of Mary Magdalene being identified in verse 9 though she had been identified already in 15:47 and 16:1. But if her name could be reiterated in 16:1—one verse after 15:47—why could it not be given again eight verses later? Has it escaped the critics’ notice that her name is also mentioned in full in 15:40—a mere seven verses before being mentioned again in 15:47? Yet, not one critic questions the genuineness of 15:47 or 16:1 though they redundantly identify Mary Magdalene again! The fact that there is more than one Mary in the text is sufficient to account for the repetition.Third, it is also true that beginning in verse 9, the other women are not mentioned again. But, again, the reason for this omission is contextually obvious. Mary Magdalene is the one who spread the word about the resurrection to the others—“those who had been with Him” (vs. 10). It makes perfect sense that the focus would be narrowed from the three women to the one who performed this role.Finally, the claim that the positioning of anastas de (“now when He arose”) and proton (“first”) are appropriate at the beginning of a lengthy narrative, but inappropriate in Mark 16 with only eleven verses remaining, is a claim unsubstantiated by Greek usage. It is not as if there is some observable rule of Greek grammar or syntax that verifies such a claim. It is simply the subjective opinion of one observer—albeit an observer who possesses a fair level of scholarly expertise. The term “first” (proton) has already been explained as appropriate since Mary Magdalene was the initiator of getting the word of the resurrection out to the others. Verses 9-14 are, in fact, intimately tied together in their common function of identifying resurrection appearances.The precise construction “now when she arose” (anastasa de) is used by Luke (1:39) to introduce the narrative concerning Mary’s visit to Elizabeth—a section that extends for only eighteen verses (1:39-56). He used the same construction to introduce the narrative reporting Jesus’ visit to Simon (4:38)—lasting four verses (4:38-41)—the broader context actually extending previous to its introduction. Additional uses of the same construction (e.g., Acts 5:17,34; 9:39; 11:28) further verify that its occurrence in the concluding section of Mark is neither unusual nor “ill-suited.” How may one rightly claim that anastas de is inappropriate in Mark 16:9-20 if it is the only time Mark used it? Surely, what Mark would or would not have done cannot be judged on the basis of a single occurrence, nor should Mark’s stylistic usage be judged on the basis of what Luke or other users of the Greek language did or did not do. Is it possible or permissible that Mark could have legitimately used the construction intentionally only one time—without subjecting himself to the charge of not being the author? To ask is to answer.Before leaving this matter of the connection between verse 8 and verses 9-20, one other observation is apropos. It is true that if Mark’s original book ended at verse 8, the book ended abruptly, leaving a general impression of incompleteness. However, the same may be said regarding the endings of both Matthew and Luke. Matthew reports the Jews’ conspiracy to account for the resurrection by bribing the guards to say the disciples stole away the body (28:11-15), and then shifts abruptly to the eleven disciples receiving the commission to preach (28:16-20). Likewise, Luke has two abrupt shifts in his final chapter. He reports the visits to the tomb by the women and Peter (24:1-12) and then suddenly changes to the two disciples traveling on the road to Emmaus (24:13ff.). Another takes place at the end of the Emmaus narrative (24:13-35) when Jesus suddenly appears in the midst of the whole group of disciples (24:36ff.). Yet no one questions the genuineness of the endings of Matthew and Luke. The final chapter of John (21) follows on the heels of John’s grand climax to his carefully reasoned thesis (20:30-31), and gives the general impression of being anti-climactic and unnecessary. Likewise, many of Paul’s epistles end abruptly, followed by detached and unrelated greetings and salutations. No one questions the genuineness of the endings of these New Testament books.While Metzger does not accept verses 9-20 as the original ending of Mark, neither does he believe that the book originally ended at verse 8: “It appears, therefore, that ephobounto gar[“for they were afraid”—DM] of Mark xvi.8 does not represent what Mark intended to stand at the end of his Gospel” (1978, p. 228). But this admission that something is missing after verse 8 could just as easily imply that verses 9-20 constitute that “something.” Metzger concedes this very point when, after noting that “the earliest ascertainable form of the Gospel of Mark ended with 16:8,” he offers only three possibilities to account for the abrupt ending: “(a) the evangelist intended to close his Gospel at this place; or (b) the Gospel was never finished; or, as seems most probable, (c) the Gospel accidentally lost its last leaf before it was multiplied by transcription” (1994, p. 105, note 7, emp. added). If verses 9-20 are, in fact, attributable to Mark, its absence in some manuscript copies is explicable on the very grounds offered by Metzger against their inclusion, i.e., the last leaf of a manuscript was lost—a manuscript from which copies were made that are now being used to discredit the genuineness of the verses in question. If, on the other hand, verses 9-20 are notgenuine, then the original verses that followed verse 8 have been missing for 2,000 years, and we are forced to conclude that the book of Mark lacks information that the Holy Spirit intended the world to have, but which they have been denied—an objectionable conclusion to say the least (yet see McMillan, 1973, p. 190).

THE VOCABULARY AND STYLE OF VERSES 9-20

But what about the style and vocabulary of verses 9-20? Are they “non-Markan”? Textual scholar Bruce Metzger insists that they are. Indeed, for those scholars who deem the verses spurious, the most influential factor—the most decisive piece of evidence—is the alleged “non-Markan vocabulary.” He defends his conclusion by referring to “the presence of seventeen non-Marcan words or words used in a non-Marcan sense” (1978, p. 227). Alford made the same allegation over a century earlier: “No less than seventeen words and phrases occur in it (and some of them several times) which are never elsewhere used by Mark—whose adherence to his own peculiar phrases is remarkable” (1844, p. 438). The reader is urged to observe carefully the implicit assumption of those who reject verses 9-20 on such a basis: If the last twelve verses of a document employ words and expressions (whether one or seventeen?) that are not employed by the writer previously in the same document, then the last twelve verses of the document are not the product of the original writer. Is this line of thinking valid?Over a century ago, in 1869, John A. Broadus provided a masterful evaluation (and decisive defeat) of this very contention (pp. 355-362). Using the Greek text that was available at the time produced by Tregelles, Broadus examined the twelve verses that precede Mark 16:9-20 (i.e., 15:44-16:8)—verses whose genuineness are above reproach—and applied precisely the same test to them. Incredibly, he found in the twelve verses preceding 16:9-20 exactlythe same number of words and phrases (seventeen) that are not used previously byMark! The words and their citation are as follows: tethneiken (15:44), gnous apo, edoreisato,ptoma (15:45), eneileisen, lelatomeimenon, petpas, prosekulisen (15:46), diagenomenou, aromata(16:1), tei mia ton sabbaton (16:2), apokulisei (16:3), anakekulistai, sphodra (16:4), en tois dexiois(16:5), eichen (in a peculiar sense), and tromos (16:8). The reader is surely stunned and appalled that textual critics would wave aside verses of Scripture as counterfeit and fraudulent on such fragile, flimsy grounds.Writing a few years later, J.W. McGarvey applied a similar test to the last twelve verses of Luke, again, verses whose genuineness, like those preceding Mark 16:9-20, are above suspicion (1875, pp. 377-382). He found nine words that are not used by Luke elsewherein his book—four of which are not found anywhere else in the New Testament! Yet, once again, no textual critic or New Testament Greek manuscript scholar has questioned the genuineness of the last twelve verses of Luke. Indeed, the methodology that seeks to determine the genuineness of a text on the basis of new or unusual word use is a concocted, artificial, unscholarly, nonsensical, pretentious—and clearly discredited—criterion.

CONCLUSION

For the unbiased observer, this matter is settled: the strongest piece of internal evidence mustered against the genuineness of Mark 16:9-20 is no evidence at all. The two strongest arguments offered to discredit the inspiration of these verses as the production of Mark are seen to be lacking in substance and legitimacy. The reader of the New Testament may be confidently assured that these verses are original—written by the Holy Spirit through the hand of Mark as part of his original gospel account.

REFERENCES

Aland, Kurt and Barbara Aland (1987), The Text of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans).Aland, Kurt, Matthew Black, Carlo Martini, Bruce Metzger, and Allen Wikgren (1983), The Greek New Testament (Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, fourth revised edition).Alford, Henry (1844), Alford’s Greek Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker), 1980 reprint.Brigance, L.L. (1870), “J.W. McGarvey,” in A Treatise on the Eldership by J.W. McGarvey (Murfreesboro, TN: DeHoff Publications), 1962 reprint.Broadus, John A. (1869), “Exegetical Studies,” The Baptist Quarterly, [3]:355-362, July.Bruce, F.F. (1960), The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, revised edition).Burgon, John (1871), The Last Twelve Verses of the Gospel According to S. Mark (London: James Parker), 1959 reprint.Colwell, Ernest C. (1937), “Mark 16:9-20 in the Armenian Version,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 55:369-386.Comfort, Philip (1990), Early Manuscripts and Modern Translations of the New Testament (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House).Dummelow, J.R., ed. (1927), A Commentary on the Holy Bible (New York, NY: MacMillan).Elliott, J.K. (1971), “The Text and Language of the Endings to Mark’s Gospel,” TheologischeZeitschrift 27, July-August.Ewert, David (1983), From Ancient Tablets to Modern Translations (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan).Guthrie, Donald (1970), New Testament Introduction (Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press, third edition).Kahle, P.E. (1951), “The End of St. Mark’s Gospel: The Witness of the Coptic Versions,” Journal of Theological Studies, [11]:49-57.Kenyon, Sir Frederic (1940), The Bible and Archaeology (New York: Harper).Kenyon, Sir Frederic (1951 reprint), Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, second edition).Lenski, R.C.H. (1945), The Interpretation of St. Mark’s Gospel (Columbus, OH: Wartburg Press).Lewis, Jack (1988), “The Ending of Mark,” in The Lifestyle of Jesus (Searcy, AR: Harding University).McGarvey, J.W. (1875), The New Testament Commentary: Matthew and Mark (Delight, AR: Gospel Light).McGarvey, J.W. (1956 reprint), Evidences of Christianity (Nashville, TN: Gospel Advocate).McMillan, Earle (1973), The Gospel According to Mark (Austin, TX: Sweet).Metzger, Bruce M. (1972), “The Ending of the Gospel according to Mark in Ethiopic Manuscripts,” Understanding the Sacred Text, ed. John Reumann, et al. (Valley Forge, PA).Metzger, Bruce M. (1978 reprint), The Text of the New Testament (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, second edition).Metzger, Bruce M. (1994), A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (New York, NY: United Bible Society, second edition).Morison, James (1892), A Practical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Mark (London: Hodder & Stoughton, seventh edition).Phillips, Dabney (1975), Restoration Principles and Personalities (University, AL: Youth In Action).Roberts, Alexander and James Donaldson, eds. (1970 reprint), The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans); Volumes 7 and 8: Fathers of the Third and Fourth Centuries.Roberts, Alexander and James Donaldson, eds. (1971 reprint), The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans); Volume 5: Fathers of the Third Century.Roberts, Alexander and James Donaldson, eds. (1973 reprint), The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans); Volume 1: The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus; Volume 3: Latin Christianity: It’s Founder, Tertullian.Salmon, George (1889), A Historical Introduction to the Study of the Books of the New Testament(London: John Murray, fourth edition).Sanday, William (1889), Appendices ad Novum Testamentum Stephanicum (Oxford).Schaff, Philip, ed. (1969 reprint), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans); Volume 12: Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on the Epistles of Paul to the Corinthians.Schaff, Philip and Henry Wace, eds. (1969 reprint), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans); Volume 10: St. Ambrose: Select Works and Letters; Volume 12: Leo the Great, Gregory the Great; Volume 13: Gregory the Great, Ephraim Syrus, Aphrahat.Schaff, Philip and Henry Wace, eds. (1954), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), 1968 reprint; Volume 6: Saint Jerome: Letters and Select Works.Scrivener, F.H.A. (1883), A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament (Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, and Co., third edition).Streeter, B.H. (1924), The Four Gospels (London: Macmillan), 1953 reprint.Warren, Thomas B. (1953), The Warren-Ballard Debate (Jonesboro, AR: National Christian Press).Welte, Michael (2005), personal e-mail, Institute for New Testament Textual Research (Munster, Germany), [On-line], URL: http://www.uni-muenster.de/NTTextforschung/.Westcott, B.A. and F.J.A. Hort (1882), The New Testament in the Original Greek (Cambridge: MacMillan).Westcott, B.A. and F.J.A. Hort (1964 reprint), The New Testament in the Original Greek (New York: MacMillan).Zwemer, Samuel (1975), “The Last Twelve Verses of Mark,” in Counterfeit or Genuine, Mark 16? John 8?, ed. David Otis Fuller (Grand Rapids, MI: Grand Rapids International Publications).

Tweet

Copyright © 2005 Apologetics Press, Inc. All rights reserved.

We are happy to grant permission for items in the "Inspiration of the Bible" section to be reproduced in part or in their entirety, as long as the following stipulations are observed: (1) Apologetics Press must be designated as the original publisher; (2) the specific Apologetics Press Web site URL must be noted; (3) the author’s name must remain attached to the materials; (4) textual alterations of any kind are strictly forbidden; (5) Some illustrations (e.g., photographs, charts, graphics, etc.) are not the intellectual property of Apologetics Press and as such cannot be reproduced from our site without consent from the person or organization that maintains those intellectual rights; (6) serialization of written material (e.g., running an article in several parts) is permitted, as long as the whole of the material is made available, without editing, in a reasonable length of time; (7) articles, excepting brief quotations, may not be offered for sale or included in items offered for sale; and (8) articles may be reproduced in electronic form for posting on Web sites pending they are not edited or altered from their original content and that credit is given to Apologetics Press, including the web location from which the articles were taken.

For catalog, samples, or further information, contact:

Apologetics Press

230 Landmark Drive

Montgomery, Alabama 36117

U.S.A.

Phone (334) 272-8558

http://www.apologeticspress.org

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Amazing, Creative, GIRLS!

These girls dance, drum, design dresses, create backyard museums, and leave their mark on the world with poetry! Here are some books to inspire little girls and the people who love them!

Shereen Rahming’s Ahni and Her Dancing Secret Alice Faye Duncan’s A Song for Gwendolyn Brooks Debbi Michiko Florence’s Jasmine Toguchi Series Zetta Elliott’s Milo’s Museum Marcus Ewert’s 10,000 Dresses

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the music-themed asks, 12, 27, and 32!

12. if you could hear any album performed live in its entirety, which would it be?

because i’m so very bad with listening to albums i’m just gonna name just a few artists whose concerts i’d maybe pay money to attend: half alive, ewert and the two dragons (estonian band but you wouldn’t know it, they sing so well in english), khalid, dua lipa, chapel, amber mark

27. name a song that you wish was longer

i was sure i’d have a million answers to this one but nothing comes to mind 😭 i think it’s always just the song i’m fixated on at the moment. sorry i think i’ll go with dua lipa’s good in bed, the bass is SO GOOD i’ve been listening to it ever since han bettytate made the viktor henriksen fancam.

32. name an album you’ve wanted to listen to for a long time, but you haven’t gotten around to it yet

again, no whole albums (eh, maybe i’ll listen to adele’s album at some point) but i always mean to listen to the songs that mutuals have put into those tag game posts. i will listen to them all at some point….

thank you for sending these 💞💞

0 notes

Text

Battlebots Season 5 Episode 5: What the hell was that?

Spoilers follow. If you don’t wanna know what happened, you don’t wanna read this . I mean, you may not want me to read this anyway, but I thought I should let you know about the spoilers just in case.

So, about last week…I wrote a pretty mediocre recap of the action and then my cat jumped on my keyboard. Thanks to Squarespace’s baffling decision not to implement an autosave feature, the whole post was lost and, frankly, wasn’t worth re-writing. Let’s move on.

Fight 1: Black Dragon v. Claw Viper

A couple of 1-0 bots squared off in the opening fight. Claw Viper had the more impressive win, showing tremendous mobility against HiJinx. Black Dragon’s win was a little more controversial, a split decision over Kraken that wasn’t especially convincing.

Claw Viper performed their customary box rush which was rendered ineffective by Black Dragon lining up at a diagonal and immediately moving out of the way. Claw Viper bumped into the wall, but unfortunately for them, Black Dragon’s drive and weapon were actually working this time around and the Brazillian spinner got a couple of good hits.

The hits didn’t do anything flashy, but Claw Viper just sort of stopped working. “Not working” is enough to start a countdown and that’s what happened. Pretty impressive win for Black Dragon, which is good, because it wouldn’t be Battlebots without a bot from Brazil in the tournament.

Winner: Black Dragon (Knockout)

Fight 2: JackPot v. Ghost Raptor

The low-budget rookie JackPot came in on the back of a win over SubZero, while Ghost Raptor was 0-1 after getting knocked out by Shatter. I didn’t really want to see either of this bots lose, what with JackPot having a compelling backstory and Ghost Raptor coming back after a four year layoff looking like Cherno Alpha in Pacific Rim.

The bots went weapon to weapon right off the bat and this didn’t go well for Ghost Raptor. JackPot’s giant spinning disc knocked Ghost Raptor’s spinning bar clean off the top of the bot. Ghost Raptor gamely attempted to do some shoving and lifting, but every time it got int he way of JackPot’s weapon, the floor got littered with bits of Ghost Raptor.

One hit split Ghost Raptor in half, and that, as they say, was that. I don’t know how JackPot will fare against a top-tier bot, but this was a very impressive win.

Winner: JackPot (Knockout)

Fight 3: Grabot v. SubZero

This was the maiden fight for Ben Davidson’s Grabot, a grappler of some sort, featuring a couple of “hands” and some chain thingies. It looked complicated. SubZero was coming off a lost to JackPot and, honestly, years and years of losses.

Grabot sort of limped out of the gate and SubZero, possibly not able to believe it’s luck, dove in and flipped Grabot on its back.

Grabot does not have a self-righting mechanism.

So, SubZero spent the next few minutes tossing Grabot around until the flipper rang out of gas but by then, Grabot was done. The cool looking grapple things never came into play, which was disappointing, but it was nice to see SubZero finally get a win.

Winner: SubZero (Knockout I think, maybe it was a unanimous decision, I can’t remember)

Fight 4: HUGE! v. Hydra

This is the fight everyone is talking about and for all the wrong reasons. This was probably the worst fight I’ve ever seen in Battlebots and I’m a little surprised they aired it. HUGE! came in at 0-1 having lost an epic battle against Mammoth. Hydra was 1-0 after taking a split-decision against Witch Doctor.

If you’ve been around Battlebots for a while, you probably remember the famous Ghost Raptor/Icewave fight where underdog Ghost Raptor mounted a pole with a V on the front in place of their spinning bar. They used it to keep Icewave at bay, eventually flipping the horizontal spinner bot and knocking it out.

Hydra’s Jake Ewert, having seen HUGE! dismantle Bronco last year, decided to take this to an extreme and mounted a giant C-shaped bar to the front of his bot. His strategy was to negate both robots’ weapons, force HUGE! into a corner, and just collect the win.

If that sounds like a boring, chickenshit strategy, you got it exactly right. HUGE! kept trying to get around or through the safety bar but could only make a little minor contact with Hydra. Hydra just patiently corralled HUGE! into the corner and sat there. The referee told him to back off and he refused until he was threatened with…whatever action a referee can take.

That was the whole fight. What total garbage. The judges gave the fight to Hydra. I’m not sure what the thinking was. Neither bot did any damage. Hydra had total control but precisely zero aggression (actually, you could argue negative aggression). How do you judge a fight like that?

To make it worse, Ewert was a complete dick about the whole thing. I’m team whoever-is-fighting-Hydra from here on out. It’s an amazing bot, easily the best flipper I’ve ever seen, but if he’s too scared to fight? Screw him. The folks at Battlebots weren’t amused, either:

Second fight this season where there was willful nonuse of an active weapon. There WILL be a penalty for this next season. #BattleBots

— BattleBots (@BattleBots) January 8, 2021

Winner: Hydra (unanimous decision)

Fight 5: Aegis v. Fusion

This marked the first fight for Chris Sparzo’s Aegis, a Kevlar-armored, shield-shaped flipper. Fusion came in at 0-1 after having failed to do much of anything in it’s first fight. Still, Fusion is a Team Whyachi bot, so you’d have to think it was a heavy favorite, especially as Kevlar seemed an extremely curious choice for armor.

Literally nothing happened for the first 15 seconds of the fight. Both bots came out of their square and…did nothing. Finally, Fusion’s weapons came online and Aegis was left to wonder what might have been had they attacked when their foe was helpless.

As it happened, Aegis actually got a good run at Fusion, but they fired their flipper too early, leaving them utterly helpless. Fusion ripped open the sides of the defenseless bot and kept attacking even as the count was going because they could, I guess.

Winner: Aegis (Knockout)

Fight 6: Big Dill v. Lock-Jaw

Both of these bots came in at 1-0 thanks to victories over hapless opponents. Big Dill actually worked pretty well in their win over Atom #94, but Lock-Jaw sputtered badly in their fight, but since it was against Captain Shredderator, they had the luxury of just waiting for their opponent to knock itself out.

Neither bot really impressed, but it’s always a pleasure to watch Donald Hutson drive Lock-Jaw. He got his bot flipped over early on, but it didn’t make a lot of difference. He bent one of Big Dill’s lifting forks and very nearly knocked ‘em out, but the pickle bot managed to get moving and see out the match.

It was more entertaining than I made it sound, as there were sparks a-plenty, but neither bot packed the punch to really put the other to the sword and that’s not a good sign for Lock-Jaw.

Winner: Lock-Jaw (unanimous decision)

Fight 7: Witch Doctor v. Kraken

Both of these bots came in at 0-1 after suffering split-decision defeats to Hydra (Witch Doctor) and Black Dragon (Kraken). It’s a little strange to see the main event be a battle of winless robots, but in this case, it made sense: Witch Doctor was a finalist last year and Kraken has made unbelievable strides from being a hopeless gimmick bot to a pretty strong control bot.

The two went head to head immediately, and you’d think that that would have favored Witch Doctor. However, just like in the fight against Hydra, the weapon system let them down. One of the two discs broke and the bot was now unbalanced and couldn’t spin the weapon at full speed.

Kraken spent most of the match biting into one or another part of Witch Doctor and running them around the box. From time to time, Witch Doctor would get their weapon going and managed to rip off some of Kraken’s armor. Kraken responded by tearing a belt off of Witch Doctor.

This was a really good fight and it went to the judges, who all agreed on the winner and I think they got the call right: A huge upset for Kraken.

Winner: Kraken (unanimous decision)

Obviously, the HUGE! v. Hydra fight was the big talking point here. People have been saying this was nothing new, that it was essentially the same as the Ghost Raptor/Icewave fight and Beta/Rotator tussle. Neither of those comparisons really hold water though: Ghost Raptor won by knockout after all and Beta charged headlong into their opponent which certainly qualifies as “aggression.” This was just anti-fighting and it was egregious enough that the rules will be changed so we won’t be subjected to this B.S. again next year.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

List of artists who have participated in exhibitions at 356 Mission:

2013

Laura Owens

Math Bass

Mike Bouchet

Sarah Braman

Sara Clendening

Barry Johnston

Kricket Lane

Daniel McDonald

Pentti Monkkonen

Matt Paweski

Jennifer Rochlin

Colin Snapp

Jessica Stockholder

Oscar Tuazon

Daniel Turner

Amy Yao

Eric Palgon

Yshai Yudekovitz

Nicholas Arehart

Bridget Batch + Kevin Cooley

Danielle Bustillo

Joey Cannizzaro

Jamie Hilder

Meghan Gordon

Becca Lieb

Mindy Lu

David Sikander Muenzer

Bryne Rasmussen-Smith + Andrew Smith-Rasmussen

Tatiana Vahan

Sturtevant

Shimon Minamikawa

2014

John Kaufman

Scott Reeder

Oliver Payne

Yuki Kimura

Alex Katz

Michael Dopp, Calvin Marcus, and Isaac Resnikoff

Trevor Shimizu

Becca Albee

Brody Albert and Kaeleen Wescoat-O'Neill

Lilly Aldriedge

Katie Aliprando

Mark Allen

Dewey Ambrosino

Marie Angeletti

Eika Aoshima

Jonathan Apgar

Cory Arcangel

Jacinto Astiazaran

Lisa Anne Auerbach

John Baldessari

Judie Bamber

Ray Anthony Barrett

Peter Barrickman

Darcy Bartoletti

Math Bass

Stephen Berens

Jennifer Berger

Molly Berman

Cindy Bernard

Amy Bessone

Lucas Blalock

Seth Bogart

Jennifer Bolande

Joseph Bolstad

Elba Bondaroff

Marco Braunschweiler

Brian Bress

Brian Briggs and Laura Copelin

Delia Brown

Sally Bruno

Edgar Bryan

Elizabeth Bryant

Jedediah Caesar

Jedediah Caesar and Kate Costello (Extraterrestrial)

Sarah Cain

Kristin Calabrese

Ingrid Calame

Ross Caliendo

Joshua Callaghan

Brian Calvin

Andrew Cannon

Ben Carlson

Jae Choi

Milano Chow

Donna Chung

Jonathan Clarke

Sara Clendening

Justin Cole

Kelly Marie Conder

Matt Connors

Vanessa Conte

Alika Cooper

Liz Craft

Meg Cranston

Cameron Crone

CH Cummings

Lila De Magalheas

Dave Deany

Michael Decker

Gracie DeVito

Michael Dopp

Katie Douglass

Lauren Dudko

Julia Dzwonkoski and Kye Potter

Mari Eastman

Brad Eberhard

Clifford Eberly

Shannon Ebner

Benjamin Echeverria

Ken Ehrlich

Alyse Emdur

Karl Erickson

Ron Ewert

Ann Faison

Cayetano Ferrer

Gabrielle Ferrer

Luke Fischbeck

Katy Fischer

Morgan Fisher

Jesse Fleming

Maya Ford

Simone Forti

Brendan Fowler

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess