#love the action poses and the stark shadow style

Text

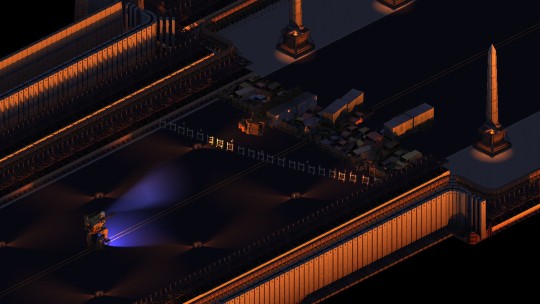

Brigador and the Art of Sky-High Storytelling

“GREAT LEADER IS DEAD.

SOLO NOBRE MUST FALL.”

The first spoken words of Brigador, synthesised through a muffled speaker and emblazoned on-screen in bold, unadorned, searing red letters, are all the exposition it strictly needs: it is a time of great upheaval on the frontier colony of Solo Nobre, and you, with your ten-ton armoured mercenary mech, are here to do some heaving. Narrative and lore are strictly confined to downtime; to dense slabs of text filed neatly away in the codex, to be optionally purchased and read at one’s leisure. There’s no place in the combat for direct storytelling, between the rumbling of diesel engines and the whip-crack of electromagnetic slugs, and even if there was, it’d be little more than poorly embellished justifications for “go here, destroy those buildings, go there, destroy those units, leave.”

But to dismiss Brigador as pure context-free action is to fail to recognise how it speaks. When we think of environmental storytelling, we think small. We think of unconvincing graffiti on crumbling walls, half-finished meals, abandoned chess boards, desks piled high with papers, carefully-placed bookmarks, downed tools and barricaded doors. We think of skeletons in compromising poses, and trails of blood that laugh in the face of a bucket of bleach. Personal stories are made when people leave personal imprints, as taken to extremes by, say, Fullbright’s shtick of giving you a whole night to rummage through your family’s household belongings unfettered. For this very reason, the most popular examples of experiences with environmental storytelling are largely those that enable you to get up close and pick it apart, preferably without being too rushed. There’s a special kind of intimacy in it, almost voyeuristic, as you sift through the documents of a person who would certainly have objected to your intrusion if they weren’t lying slumped against a nearby desk with an alien birthing cavity where their guts used to be.

Brigador is the antithesis of that. Its sky-high isometric viewpoint, panning silently over the streets, gives you little such insight into the fine details. You can’t tell the story of a person from up here—at least, not easily—but you can tell the stories of people. And war is all about people, collectively; people fighting, people fleeing, people dying. Stories of lone figures, unless they hold huge power or significance, are swept away in the tide of shared tales, told through numbers rather than poignant letters to mother. You can pluck lone individuals out, humanise them and piece together their fate, but chances are that they were just one of a hundred, or a thousand, or a million people in the same boat, going through the same motions. Those collective motions, and their collective effects, are the ones that Brigador’s environments make us privy to.

One major target objective recurs through your missions: the orbital guns. Solo Nobre’s surface bristles with these skyward-pointed cannons, designed to obliterate any spacefaring aid that so much as entertains the thought of helping liberate the colony. Naturally, they’ve got to go, but it’s the way they impose on their surroundings, irrespective of context, that fascinates me. Taller than a city block, frequently ringed by sheer defensive walls and expanses of flat asphalt, their incongruousness isn’t just stark; it’s deliberately exaggerated. They invade the space around them, like alien landing craft, making no effort to compromise or integrate no matter where they are. To us, the player, they drive home the extent to which recent rampant militarization has dominated the lives of Solo Nobre’s people. What’s it like to have one of those things in your back yard? On your block? In your cemetery? Looming threateningly, a permanent reminder that the entire colony was, and is, ruled through military force. It’s all too easy to imagine them just springing up one night in a flurry of jackbooted activity, confusing and unnerving locals who understand nothing of the political situation, only that they’re now the unwilling neighbours of the biggest, juiciest, most explosive target in the district.

Most of Solo Nobre looks as if it sprung up overnight, to be honest. Many of the maps have a decidedly frontier air to them, sharply contrasting undeveloped wastelands with industrial and agricultural estates—or outright shanty towns, on occasion—and even developed zones are often distinctly utilitarian, as if the first construction efforts focused solely on establishing the functional basics and nobody’s had a chance to do a second pass. Why is that important? Because it means that whatever worldly influences went into the colony’s initial construction—the decisions, the constraints, the goals—are still relevant. Spaces change meaning over time; they get repurposed, recontextualised, rebuilt, and in the process the original intent of their structure gets muddled. Solo Nobre hasn’t had a chance to get especially muddled yet: everything on the landscape feels as if it has a current, relevant reason to be there. The story of the colony is coded into its infrastructure, fresh as the first coat of gunmetal-grey paint. Roads, buildings, fences, zones.

And wouldn’t you know it? That’s the part that you, with the omnipotent eyes of a SimCity mayor, are perfectly situated to deconstruct—in the analytical sense, I mean. You see the way the streets are laid out and the way blocks are divvied up; the way patterns and biases have formed in the overarching organisation—or lack thereof—of the urban sprawl. What becomes noticeable almost immediately is… lines. Often games with isometric grid presentation will seek to break up the grid; to introduce chaos and noise to obscure the perfect, infinite parallel lines that give their environments such an artificial, manufactured air. Brigador relishes in it. Brigador loves the grid. It goes out of its way to propagate unbroken, arrow-straight walls and roads for miles. They speak of an ultramodern, efficient, painfully austere development process; the kind that rolls out state utilities like a titanic machine, paving anything that stands in its way with no regard for landscape or lives. To be more exact, they make it clear that they’re not the product of democratic civil planning, but of orders from on high, carving up and commodifying the colony like the centrepiece of some debaucherous banquet. In a more striking fashion than any graffiti decal or audio log, these pieces of Brigador’s public infrastructure illustrate the disconnected, totalitarian whims of its administration. A casual flick of a cufflinked wrist and suddenly a neighbourhood is living in the shadow of five storeys’ worth of reinforced concrete. Are you in the way? Time to relocate, Mr Dent.

But apathetic architecture isn’t the same as thoughtless architecture. One of the clearest intents behind much of Solo Nobre’s urban planning is its concerted effort to distance the haves and the have-nots, coddling the former and shutting out the latter. Cramped slums frequently sit side-by-side with idyllic American Dream suburbs, divided by district walls—once again, we return to walls—that have been coated on one side with improbably tall hedges, so their viewers may entertain the fragment of an illusion that all is well in their slice of freshly-mowed Eden. Such proximity between the wealthy and the poor suggests that space is scarce on Solo Nobre, but not so scarce that the former can’t afford to have sweeping lawns and tacky, towering neoclassical McMansions. You could be forgiven for starting to wonder if something’s wrong with the scale, when your titanic walking weapons platform that could put a foot through a tower block suddenly has to crane its neck to shoot over a family home, but no—it’s just another way of illustrating the yawning gulf in privilege to your eye in the sky. One mission takes you out onto the green expanses of a country club, which—along with a sizeable occupying force, obviously—also features imposing gun turrets built into the landscape, poking out the top of more hedge-covered fortifications. Why would a golf course need such entrenched defensive measures, in what we’ve been led to believe was a relatively peaceful time? They can only have been a means of deterrence; of scaring away the riff-raff and making the privileged feel secure, without the excessive use of unsightly district checkpoints and barricades.

Yet even with this sweeping disparity, there’s a common thread in Solo Nobre of humanisation of oppressive spaces. Between hulking pipelines, paved concrete expanses and endless bleak industrial estates, there’s mounting evidence that Great Leader’s priorities were not the well-being of his workers, but here and there are tiny, isolated reminders that people still manage to engage in recreation. A single basketball hoop at the end of a loading dock, lined by rows of identical storage units; a children’s climbing frame in the middle of a muddy plot, ringed by skeletal steel pylons; a lone fifties-style diner, complete with a scattering of those cheap white plastic chairs, bleached by the halogen glow of a communications mast. They’re fragments of lives, not destined to be pieced together into a cohesive narrative, but to simply remind us that even in the city’s coldest, most utilitarian corners, people are not drones. Until now, we’ve focused on tales of communities and collectives, but to view people only in the plural like this is to risk treating them as so many trivial organisms under a microscope, always moving in tides, their individual impulses lost in the swarm. It’s details like these that keep us grounded, so to speak, even while gazing down at the sprawl.

That’s all just history, though, innit? That’s stuff that happened over months, years, decades even. But some of the imprints on Brigador’s landscape are more temporal, left by events far more relevant to your current mission. Solo Nobre’s liberation takes place over a single night—or so it’s implied—and while you may be the first to fire a shot, you’re certainly not the first to make a move.

Traffic. It’s the traffic. You could initially be forgiven for thinking that the streets of Solo Nobre, despite their spaciousness and high standard of upkeep, don’t seem to be getting a lot of use; they’re utterly devoid of active civilian vehicles, trodden only by the assorted war machines of your opponents. Brigador doesn’t feature non-combatant units—other than the tiny raincoat-clad civilians who mill around helplessly until being crushed carelessly underfoot—but nevertheless, you’ll soon find remains of traffic jams around the maps: gridlocked, bumped-to-bumper, clearly long-since abandoned when it became apparent none of it was ever going to budge an inch further. Why would it be so tightly packed, and trail so far back, in a city where the highways are so wide that you could triple-park an interstellar freighter across one without making everyone late for work?

Once again, placement is the key. Brigador’s abandoned traffic isn’t randomly distributed, but concentrated around particular points. Lanes upon lanes of gently cooling automobiles are regularly found clustered in front of district checkpoints, around spaceports, even outside train depots, seemingly stopped in their tracks. A picture forms; a picture of a reeling state power rushing to regain its faculties, crack down on sudden unrest, minimize chaos. Of people hearing the news, sensing the forthcoming conflict, choking the roads with their attempts to flee. Of the two forces colliding in the lengthening shadows of a checkpoint, a cacophony of horns and furious shouts assaulting a grim military police barricade. Evacuation efforts scuppered. Deadlock. Until the Corvids turn up in their scrapyard siege engines and flatten a few city blocks, obviously.

But the exodus of Solo Nobre isn’t a complete failure. As your trail of destruction spirals out towards the edges of the colony, from the urban sprawl to its inevitable, oft-forgotten by-products, signs of relief begin to manifest. Nestled up against neglected pipelines and crumbling walls are clusters of blue tents—the kind of blue they only ever use on tarpaulins and concert port-a-potties—propped up with flimsy poles, dulled by the mud of the wastes. They’re ramshackle, disorganised, and frequently located in spots of dubious tactical importance, all of which suggest that while the materials might come from a Loyalist source, they’ve certainly not been set up under any kind of military coordination. Indeed, their most unifying quality seems to be that they’ve been pitched out of the way of populated zones—presumably by people who have had quite enough near misses with cluster mortar strikes for one night. These are camps set up by refugees, no way around it; people fleeing the power struggle, one way or another, trying to hole up somewhere so backwater that nobody would waste time fighting over it. Alas, as the presence of you and your enemies implies, they’re disastrously wrong. But that can’t be helped now, can it?

I suppose the only thing left to wonder is what, if anything, Brigador hopes to make us feel with all this effort. It leaves features on the landscape to tell us that these things happened, but despite our inarguable involvement, never ties those events back to us; never blames us for displacing innocent people, destroying their homes and gibbing them in the streets with careless cannon fire. In a game that encourages you to look at your environment in terms of little more than the cover it offers, it’s easy to tune out such ghastly side effects, particularly when the only feedback you get from razing civilian buildings to the ground is a miniscule bonus—yes, a bonus, perplexingly—to your end-of-level payout. No guilt, no joy, just a matter-of-fact occurrence. But as a mercenary, fighting first and foremost for a sodding huge cheque, perhaps it’s only appropriate that the only stimulus you get from needless destruction is an insignificant increment on your score counter. What better metaphor could there be for the faint flicker of acknowledgement, cold and distant as the shores of Titan, in a mind focused entirely on the task at hand?

It’s not easy, communicating using only the features that are visible to passing airliners, but Brigador plays to its strengths. It focuses on sweeping trends and dramatic shifts—which are, of course, common during times of unrest—using them to speak of the effects of dictatorial regime and violent power struggles, but scatters around visible one-off details too, as humanising fragments for those who stop and take notice. Nobody could ever describe it as an epic narrative tour-de-force, but I find it to be a fabulous example of working within limitations; of understanding how sociopolitical transformations can embed their effects in the landscape, and how we can read them back again—so long as they aren’t demolished by a Killdozer first, anyway.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Natasha is Young: Costuming Denée Benton in “The Great Comet”

I had a special request in the Ask box for another entry in my The Great Comet series, and I am happy to oblige. This time, I’m turning my attention to something I’m typically more comfortable reviewing, namely women’s costuming. Having covered the male lead last time, I want to take a look at the costumes of Denée Benton this time, because they really show off Paloma Young’s skills as a costumer. I’ve picked a couple of Natasha’s (Ms Benton) outfits from The Great Comet to focus on, but I really do think you should check out all the costumes from this production; it’s definitely one of the most sumptuous musicals currently running on Broadway.

I’ve talked a lot about theming in costuming, and this is a good place to reiterate those points. Costume designers use color to make a statement, and this production is no exception. Costuming the character of Natasha in white for virtually the whole of the musical imbues the character with a kind of purity that none of the other characters possess to the same degree (with the possible exception of Sonya...but then again, “Sonya is good”). I think that’s important in the context of the musical, but there’s another reason that I think the white coloring of Natasha’s costumes is so important, and it goes to the heart of what makes The Great Comet such a unique theatrical experience: the staging and lighting.

Anyone who has seen the staging for The Great Comet knows that it is an interactive performance, one where the audience is very much brought into the heart of the action. As a result, the lighting design is more complicated than in your average production. That means your costumes need to be able to catch the light, and it makes the detail work you put into a costume all the more important. After all, members of the audience will be seeing the actress and character from every angle, as opposed to just a handful. Let’s take a look first at The Coat that is featured prominently in many of the promotional images and in the musical itself:

I want to start off by saying how in love I am with this coat. It’s regal and rich, and it hangs beautifully on Ms Benton (I haven’t had the chance to view anything from the understudies, so I’m focusing on the actress who originated the role). This is a posed shot, but it gives us a view of just how gorgeous this piece is. As I mentioned in my 9 to 5 review, outerwear is not something that is commonly featured on Broadway, and so costumers tend to take their cues more from history or current trends rather than other productions. But Paloma Young has come up with something beautiful and original here.

It’s floor-length, which has the effect of adding to Ms Benton’s height (something costumes can do, as I have noted in other reviews) and giving her more of a stage presence. The white is almost creamy in color in every photo I have seen, which is a good choice, I believe; pure, stark white can look artificial to the eye when it is overused, and a formal coat like this in the era (remember we are dealing with the 1810s) would almost certainly not have been in pure white. But this comes close, and onstage, it has the effect of being almost blindingly brilliant--which has to be intentional. Take a look at this shot where Ms Benton is lit from behind; the coat almost seems to glow as it catches the light, but you can still see the creaminess of the color where there is shadow:

Just take a moment to drink that in. Part of it is the effect of the spotlight, but it is not easy to get this kind of effect in a stage production, and Ms Young deserves a huge amount of credit for her fabric choice and the cuts of the cloth here. There’s an angelic feel here that gives me all the good feelings, and it really forces you to pay attention.

Onto the details of the coat itself! As can be seen in the first still, the coat is relatively simple in design, but that adds to its elegance in my book. Floor-length, it closes through the addition of four silver buttons on the bust and chest, which manage to stand out without being distracting. Ms Young has added a false belt around the high waist, using gold embroidery to add a splash of color to the cream of the coat itself. The embroidery takes the form of gold roping, which I think ties it nicely to Pierre’s waistcoat, which was the subject of my first Great Comet review. It flows nicely while still being a tiny bit abstract, and I think helps to make the coat more impressive.

The collar and cuffs of the coat match (which is important, I think, when one wants a classical look) through the addition of white fur. That’s a nice hat-tip to Russian styling of the Romanov era (1613-1918), which often emphasizes fur elements both for functionality and for design. Earlier on, functionality would have been more important--a Russian winter is brutally cold and fur is naturally warming--before eventually giving way to being a design element; given the setting of The Great Comet, I think it’s fair to say we’re more into the design era.

What I like about the addition of the fur is that it adds another texture to the coat itself; while not apparent in the stills here, under magnification the coat is a rough, almost leathery fabric that would help to keep the wearer warm while still looking elegant and graceful to an outside observer, as it does to the audience in this production, whether in the orchestra or onstage in the special seating. Texture is important, I think, even when it isn’t directly observed, because the eye is capable of picking up tiny, minute details even without us being conscious of it. It’s apparent that this isn’t a completely smooth fabric, but the addition of the fur adds a softness to the coat that it might otherwise lack.

The other amazing costume that is worn by Ms Denton in her role as Natasha is the White Dress. I think when most people hear that there is a ball scene in this musical, they conjure up images of voluminous dresses with yards of silks and chiffons, but I think that’s because most of us have been spoiled by Victorian or 18th century costume dramas rather than those set in the era of The Great Comet. Regency-era attire, both in the West and in Russia, was a little bit more simple. Crinolines (the wooden or wire skeleton of a ball gown) had yet to come into fashion in Russia as they had (to some extent) in France, and instead, a lot of emphasis was given to relatively straight cuts of fabric. The idea was that a woman’s figure could be hinted at, but not excessively revealed, leaving a slight air of mystery that would change over time.

Taking a look at the White Dress, the 1810s fashion leaps right out:

The dress is a patterned white fabric, where the pattern is a series of circular elements that are a part of the dress rather than being adornments added later on. There is a very high waist, which is a classic hallmark of this era of fashion in both the West and in Russia, and the bust and chest are richly adorned with detail work I’ll take a look at in a moment.

But look at the overall effect of the dress first. The fabric flows down to floor-length, is capable of floating when Ms Benton is in motion (as this shot shows), and has a regal look without being too imposing or intimidating. Compare that to, say, some of the dresses that Helene wears in the production, and the effect is even more important. Natasha is evolving slowly throughout this musical, and the dress is a point of transition. She’s allowing herself to be absolutely gorgeous in the context of a grand ball, and the dress is made to show off her ability to revel in the moment.

The overall effect is only enhanced by taking a closer look at some of the detail from the top portion of the dress. Here, we see Natasha being aided in getting ready by the aforementioned Helene (who may very well be the subject of her own review in this series), offering us not only a view of the detail but a chance for a little bit of compare-and-contrast:

First off, wow. I know I have a tendency to gush over design elements that I find attractive, but I can absolutely see why the Anon who asked about reviewing this dress cited it as their favorite-ever piece of costuming. The white, patterned fabric gives way to a saltire (an x-shaped) of fringed beadwork that sticks out from the dress and really gives it an effect that pops. It would have been easy to go over the top here, but in my opinion, Ms Young struck the perfect balance of small, delicate beadwork attached to the dress, and the pattern she chose for it adds a bit of a whimsical look to the dress that I don’t think we would see with a more flat or one-dimensional strand of beads.

But the beadwork, while impressive, is not my favorite feature of this dress--it’s the lacework! Take a look more closely at Ms Denton’s chest and shoulders. There is some really beautiful, delicate, elaborate lacework that has been added to take the dress from amazing to spectacular. Lace is very difficult to work with, and even more difficult to incorporate into a costume because it is by nature delicate. One wrong move, and it will just absolutely shred. Using it in this dress was a little risky, given the intense movement that goes on throughout this production, but in my considered opinion, it’s a risk that absolutely paid off. The addition of the lace really takes this dress to another level, and even without the other costumes in this production, Ms Young’s nomination for a Tony was well-deserved (and, again, there is a very good case for a win there).

I’ve had a chance now to look at a few of Paloma Young’s designs, and I am absolutely in love with them. Being able to look in depth at a few of her designs both in The Great Comet and Bandstand, I am a real admirer of how she uses fabrics and cuts to tell a story. The story I see here, in both the coat and the White Dress, is one of evolution. This young, innocent character is finally starting to come into her own as a result of the events in the musical, and her costuming reflects that. There is an innocence and purity to the dress, yes, but there are also design elements that hint to the audience that change is coming for Natasha. The country girl has gone city, and with that she’s starting to become someone else--someone, perhaps, she was always meant to be. That’s not an easy effect to have through costuming, and it’s one that I think deserves to be appreciated and admired.

Once again, thank you to Paloma Young for these visually stunning and meaningful costumes!

That wraps up today’s review of Natasha’s costumes in The Great Comet. Given the reception the last piece got, I’ll mix a couple more reviews of Paloma Young’s designs into my rota for the blog, with Helene and Anatole both high on my list as deserving some analysis.

As always, dear readers, if you have thoughts, comments, or feedback, please do not hesitate to drop me an Ask or send me a message on here or my main blog. Stay tuned for more from the beautiful world of Broadway costumes!

190 notes

·

View notes