#language acquisition

Text

“Grandma’s House is not like a drop-off daycare or an immersion school where only the children learn. Through a grant from the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota Foundation, parents get paid to learn alongside and speak with their children in Ojibwe five hours a day, four days a week.

…

‘Learning Ojibwe in college and pursuing learning the language and teaching the language, I hadn't really thought about babies speaking it as their first language,’ Erdrich said.

‘It seemed like this impossible thing because of how much work it would be, how hard it would be to have a whole community and other babies to be speaking Ojibwe, but it's happening! And it's amazing because it's the peer language here so the kids are speaking Ojibwe to each other,’ she said.

…Grandma’s House is not like other college language programs. Learning a Native language in an academic setting is beneficial for language revitalization, but academic learning does not usually include learning the traditions, heritage or spirit within a Native community.

…

Although it’s common to refer to a language no longer commonly spoken as a ‘dead language,’ some people in the language revitalization movement instead refer to them as ‘asleep.’ The idea is that sleeping languages can be awakened through family and community efforts.

Waking up Native languages can also bring intergenerational healing.”

#linguistics#language#sociolinguistics#language and identity#language and culture#language and power#langblr#language learning#language acquisition#language revitalization#ojibwe#anishinaabe#minnesota#indigenous#indigenous languages

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fake-tanuki soup or Fake tanuki-soup?

連濁(れんだく; en: rendaku)is a phonological rule in japanese that makes the first voiceless consonant of a word change into a voiced consonant when used in a compound word. For example, おり + かみ → おりがみ (ori + kami → origami) ("fold" + "paper" → "paperfolding") - the /k/ sound in かみ becomes a /g/ sound (which is the voiced version of a /k/ sound) by adding a voicing mark -> が.

What’s interesting about 連濁 is that native speakers can use it subconsciously as a sort of “order of operations” system for unfamiliar words, like PEMDAS or BIDMAS in maths. A classic example of this is the にせたぬきじる problem[1]. Native speakers can immediately and with confidence tell the difference in meaning between two compound words they have never heard before, despite the only difference being the voicing of a single consonant. Take the three words 偽 (にせ, meaning “fake” or “imitation”), たぬき (tanuki, the Japanese racoon dog), and 汁 (しる, meaning “soup” or “broth”). They can be combined into the following compound words: にせたぬきじる and にせだぬきじる (note the voicing mark, or dakuten, on the latter). Keep in mind, these two words do not exist in ordinary japanese - they’ve been created as part of a linguistics experiment.

You might think the meaning would be ambiguous in those compound words: is it (imitation tanuki)+soup or imitation+(tanuki soup)? Let’s imagine we’re referring to the former. First, we combine にせ+たぬき. There’s a rule that rendaku can’t occur if there’s already a voicing mark in the second component of the compound, but we’re safe here - たぬき has no voicing mark. Therefore, it becomes にせだぬき. Then, we combine にせだぬき+しる. Again, しる has no voicing mark in it, so we’re safe to add it in, and we get にせだぬきじる.

Conversely, let’s say we were referring to fake “tanuki-soup”. First we combine たぬき+しる. This combines safely to たぬきじる. Then we combine にせ+たぬきじる. But wait, the second component does already have a voicing mark, on じ! So we can’t add one to た. Therefore we end up with にせたぬきじる.

That’s a lot of thinking and linguistic hoops to jump through to make up 2 words, but here’s the thing: Japanese native speakers who have never heard these words before can instinctively deduce the difference in meaning with startling accuracy. They correctly determine the meaning of にせだぬきじる as “a broth made from imitation tanuki” and にせたぬきじる as “a fake version of a dish called ‘tanuki soup’”. Even more surprising is the research findings of Shigeto Kawahara, which show that children as young as 9 years old can consistently deduce the difference as well[2]. I think this shows how incredibly powerful the subconscious mind is at learning linguistic rules, and how bad the conscious mind is at learning them!

#langblr#japanese#japanese language#language acquisition#language learning#language#linguistics#learning japanese#日本語#jimmy blogthong

676 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first words were 'These were my first words; what were yours?'

Language Acquisition [Explained]

Transcript Under the Cut

[A child, drawn as a smaller Hairy, stands next to some blocks. Megan and Cueball stand to the right of him.]

Child: Vocabulary update: I learned another word today, bringing my total to twelve.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Few Fun Little Language Learning Tips

Hello, these are a few little tips I've found on my language learning odyssey that you may find fun or helpful

Accents! This can be a great way to 'warm up' before speaking more in depth, or a training exercise, but a fun way I've found to get myself to make French sounds (it works for any language really) is to speak English (or insert native language here) with an exaggerated accent that comes from someone speaking your target language, I find this a fun way to get the sounds of a language you're trying to speak into your head in order to make speaking easier (great for speaking exam practice)

Use addictive social media for profit! So this would be best for intermediate to advanced learners, but a way to learn more slang, grow your vocabulary, and just generally get more language input in an easy way is to create a dedicated social media account in your TL and simply lurk, do you spend hours doom scrolling short form video content? Do it guilt free by doing it in your TL, do you like cat memes? read them in your TL, it's addictive, and low energy, so you can do it even when your brain feels like a fried egg

Need a pen pal? Try Ai! So, speaking to real people in your TL can be a daunting task, for reasons ranging from the fear of saying something wrong to just plain stranger danger, so a safer (and totally free) alternative can be through ai chat bots, you can do this with dedicated language learning bots or with just plain old ChatGPT

Nostalgia Bait! One of the most beautiful things about visual art is the fact that it is a universal language in itself, certain symbols can hold significance wherever you go, so re-watching animated TV shows from your childhood or watching new TV content made for kids in your TL can be a great way to add to your vocabulary, and in call & response shows, generate responses and make them more complex if you like, to add more intrigue

When in doubt, write it out! I personally struggle a lot with conjugation, so if you do to, here's a solution I found, use Quizlet learn to help drill conjugation, and when your free rounds run out, you can manually use the flash cards to use the same effective learning strategy (or pay for Quizlet plus, but I, personally would rather eat a dusty lamp then pay for something that, in my opinion, should be free to all learners)

#language#language learning#tips#grammar#langblr#french language#learning#education#language acquisition#language study#language stuff

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

#langblr#language learning#studyblr#poll#languages#linguistics#language acquisition#polyglot#hyperpolyglot#duolingo#i’m really just curious as to what people think#spanish#english#french#german#portuguese#catalan#polish#yiddish#arabic#swedish#chinese#japanese#korean#swahili#xhosa#quechua#yoruba#persian farsi#hebrew

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! So while giving advice to a fic writer I actually arrived at a question that compels me greatly, one that I don't know if you can answer since it might require worldbuilding, but it's *linguistic* worldbuilding so you might have an answer.

When Valyrian-speaking parents are (were) teaching their babies the first words, like pointing to various nouns or to themselves and calling out their names, do they call out these words in the nominative or the vocative case?

Basically, I'm trying to figure out if it might actually be more appropriate for a child to informally call her mother "Muña" rather than vocative "muñus" because that might mean the difference between the equivalent of "Mom!" versus "Mother!" in english. I suspect it would have to do with whatever form of the word it is that the baby learns first, since the baby will probably call the parent that for some time regardless of corrective efforts.

So picture the scene. Mother is teaching her baby the word for mother. When she points to herself, does she say "Muña" or "muñus"?

I thank you in advance and hope this is not a frustrating question.

To answer questions like this, it might be helpful to think of the rest of the English sentence that's being left out when we say things like this in English. For example, when someone is pointing at an apple and saying, "Apple!", it's typically short for one of two things: (1) "That's an apple!", or (2) "That's called an apple!"

Now, knowing this is pretty trivial for English, but consider a case language. If you're just saying "apple", suddenly it matters what case the apple would be in in the sentence it was drawn from. In High Valyrian, the case of "apple" for (1) would be nominative, and for (2) would be instrumental.

Back to your scenario, it really depends on what was being said. If they're saying "This is the worst for this person", then it's muña. If it's "This is what you call me", that's muñus.

Also, though, overt instruction only does so much. Most of the time children learn by listening, watching, copying, and, later, extrapolating.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making progress in a natural language entails lots of listening, studying, and generally soaking in the words and sounds of the new language until your head is buzzing with them. Over time you realise that you're building up an intuitive understanding of what sounds correct and natural, along with a growing vocabulary.

I haven't gotten deep into constructed languages like Toki Pona or Esperanto, only dabbled a little to satisfy my curiosity, but I've noticed babbling seems to play a much greater role in the learning process for these. I almost involuntarily get the urge to babble short expressions to myself using the new rules (ni li pona, ni li ike, mi wile e ni...), and the new language patterns gradually become intuitive in that way, instead of acquiring them through repeated exposure. It helps make up for the scarcity of resources in most conlangs.

#langblr#language learning#language acquisition#esperanto#toki pona#interlingua#mine#toki pona is an earworm tbh

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 86: Revival, reggaeton, and rejecting unicorns - Basque interview with Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Revival, reggaeton, and rejecting unicorns - Basque interview with Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez'. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch. I’m here with Dr. Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez who’s an Assistant Professor at California State University, Long Beach, USA, and a native speaker of Basque and Spanish. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about new speakers and language revitalisation. But first, some announcements. Thank you to everyone who helped share Lingthusiasm with a friend or on social media for our seventh anniversary. We still have a few days left to fill out our Lingthusiasm listener’s survey for the year, so follow the link in the description to tell us more about what you’d like to see on the show and do some fun linguistics experiments. This month’s bonus episode was a special anniversary advice episode in which we answered some of your pressing linguistics questions including helping friends become less uptight about language, keeping up with interesting linguistics work from outside the structure of academia, and interacting with youth slang when you’re no longer as much of a youth. Go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to this bonus advice episode, many more bonus episodes, and to help keep the show running.

[Music]

Gretchen: Hello, Itxaso, welcome to the show!

Itxaso: Hi! It’s so good to be here. I feel so honoured because we use so many of your episodes in our linguistic courses. For me, being here is exciting.

Gretchen: Hello to Itxaso and also to Itxaso’s students who may be listening to this episode.

Itxaso: I dunno if I want them to find this episode, though. [Laughter]

Gretchen: They’re gonna find it. Let’s start with the question that we ask all of our guests, which is, “How did you get interested in linguistics?”

Itxaso: I feel like, for me, it was a little bit accidental – or at least, that’s how you felt at that time. I grew up in a household that we spoke Basque, but my grandparents didn’t speak Basque. My parents spoke it as non-native speakers. They were new speakers. They learnt it in adulthood, and they made me native. But I was told all my life, “You speak weird. You are different. You’re using this and that.” Later on, I was told that, “Oh, you’re so good at English. You should become an English teacher because you can make a lot of money.” And I thought, “Oh, yeah, well, that doesn’t sound bad.” When I went to undergrad, I started taking linguistic courses, and then I went on undergraduate study abroad thanks to a professor that we had at the university, Jon Franco. That’s where I realised, “Wait a minute. All of these things that I’ve been feeling about inadequate, they have an explanation.”

Gretchen: So, people were telling you that your Basque wasn’t good.

Itxaso: Yeah.

Gretchen: Even though you’re the hope and the fruition of all of this Basque language revitalisation. Your parents went to all this effort to learn Basque and teach you Basque, and yet someone’s telling you your Basque is bad.

Itxaso: Absolutely. You know, people wouldn’t tell you straight to your face, “Your Basque is really bad,” but there was all these very subtle ways of feeling about it, or they would correct you, and you were like, “Hmm, why do they correct it when the person next to me is using the same structure, but they don’t get corrected.” As a kid, I was sensitive to that, and then I realised, “Wow, there’re theories about this.”

Gretchen: That’s so exciting. It’s so nice to have “Other people have experienced this thing, and they’ve come up with a name and a label for what’s going on.”

Itxaso: It’s also interesting that as a kid I did also feel a little bit ashamed of my parents, who’re actually doing what language revitalisation wants to be done. You want to become active participants. But I remember when my parents would speak Basque to me, they had a different accent. They had a Spanish accent. I was like, “Ugh, whatever.” Sometimes it would cringe my ears; I have to admit that. As a kid, I was in these two worlds of, okay, I am proud and ashamed at the same time of what is happening.

Gretchen: And the other kids, when you were growing up, they were speaking Basque, too?

Itxaso: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. I grew up in Gernika, right, and we have our own regional variety. I remember on the playground sometimes they would tell me, “Oh, you sound like the kids in the cartoons.”

Gretchen: So, you’re speaking this formal, standard Basque that your parents had learned as second language learners, and the other kids are still speaking the regional variety of Basque but hadn’t gone through the standardisation process and become the one that’s in the media.

Itxaso: Correct. My first variety was actually this standardised variety that nobody spoke when it was created in the ’60s. My parents learnt this in their 20s, and then that’s the variety that I was exposed to at home. But then you go in the street, and they’re like, “Oh, you sound like Doraemon,” because that’s what we watched.

Gretchen: The character in the cartoon, yeah.

Itxaso: Yeah, in the cartoon. It was like, “Oh, okay, do I? All right.” Then I started picking up the regional variety.

Gretchen: Right. You pick up the regional variety as well from the kids. Then what did your parents think of that if they think they’re speaking the fancy one?

Itxaso: Oh, my goodness. It was absolutely hilarious because my mom, she always thought that the Standard Basque is the correct way because that’s the one that you learnt in the school, so she did have this idea that literacy makes this language important. You know, for Basque revitalisation, that’s important. But I remember we were at home, and she would correct me because, for instance, as any spoken language, you would also shorten certain words. She would always say, “Oh, that’s not how you say it. You’re supposed to say this full word. You have to pronounce the entire word.” Then I said, “But Mom, everybody else uses this other variation,” especially with verbs, which are a little bit complicated, right. Then she would say, “Oh, Itxaso, you know what? I gave you this beautiful Basque, and then you went out to the school, and they ruined it all for you.” Then in order to come back, I would tell her, “Mom, but I am the native speaker here.” So, these tensions of who is right.

Gretchen: Who is the real Basque speaker, who is the best Basque speaker, and in this context where, in theory, your goals should be aligned because you’re all trying to revitalise Basque, and in theory, you all have the same goal, and yet, you’re getting criticism from different sides, and people are criticising different groups in this – but in theory, you have the same goals.

Itxaso: I think growing up in this paradox of I’m also criticising my mother, who actually, thanks to her, I get this language. In the revitalisation process, I think this negotiation is fascinating that you’re constantly being exposed to.

Gretchen: Constantly being exposed to all these different language ideologies around what is good, what is not good. You went to university, and you started encountering linguistic words for these experiences that you had. What were some of those words?

Itxaso: Some of these words I remember was this “standard language ideology,” that the idea or, in a way, that the standards are constructs that don’t exist. And I was thinking, “Wait a minute, in my language, we have a very clear standard.” We actually have a name for it. We call it “Unified Basque,” or “Euskara Batua.”

Gretchen: “Batua.”

Itxaso: “Batua” means “unified.” It’s associated with a kind of speaker. These are speakers that, like my parents, learned Basque through the schooling system, which today is actually the majority of the Basque-speaking population, at least on the Spanish side. “Standard language ideology” – I was thinking, “What is that? Oh, okay, it’s the thought that we have that these standards exist. How do I make sense of that?” I remember when I was in college, the term “heritage speaker” was thrown a lot.

Gretchen: “Heritage speaker” of Basque. Are you a “heritage speaker” of Basque?

Itxaso: I don’t consider myself a heritage speaker of Basque because – so I have Basque heritage, yes, and no. My dad’s side of the family is from Spain as well, but they also grew up in the Basque Country. This comes also with the last name. Do I have Basque heritage? Yes. But I think our connections with language are a little bit more complicated than the ethnicity per se. It’s like, we have this saying that says that it is Basque who speaks Basque. That was this poet, Joxean Artze, that we used to hear a lot during the revitalisation process. The question is, “What kind of Basque?”

Gretchen: Yeah, like, “Who is Basque enough to speak Basque?” And your parents speak Basque, but your grandparents didn’t speak Basque anymore, but if you go far enough back in your ancestry, somebody spoke Basque. But who counts –

Itxaso: But – yeah. My grandparents didn’t speak Basque. Their parents – maybe they had some knowledge. I dunno how far along. What we do know is that the region where my grandparents grew up in, Basque was already in the very advanced stages of language shift. Also, my grandparents were born in the civil war, so speaking Basque was probably not – it could get you killed.

Gretchen: Yeah. Which is a great reason to say, “Hey, you know what.”

Itxaso: Right. Then later on, this paradox is coming into play. As a 5-year-old kid, you’re not aware that your grandpa, you know, could have been killed if they spoke our language, but at the same time, my dad’s side of the family also was going through some kind of shame because he learnt the language as an adult, and he became in love with the language. This idea of heritage – do you need to be a heritage to be part of the language? It was a little more complicated than that. When I asked my mom, “Why do you learn the language?”, for her, she was always, “Because my identity now is complete.” But for my dad, it wasn’t the same reason.

Gretchen: Why did you dad learn Basque?

Itxaso: My dad learned Basque because after the dictator died, the revitalisation was very important, and there were a lot of jobs.

Gretchen: Ah, so just economic reasons.

Itxaso: For him, it was pure economics. Then, you know what, if I learn Basque, I’m gonna have more opportunities to have a government job, and a government job is a good job. Then after that, throughout the time, he actually became even more in love with the language, more invested in the revitalisation. He also did a lot of these – bertsolaritza is this oral poetry that we have. It has a very, very long oral tradition in the Basque Country. He read a lot of literature. He taught Basque in the school system. He was also invested in teaching Basque to immigrants as well because he felt like an immigrant himself as well.

Gretchen: And this question of who has Basque heritage, if you’re an immigrant to Basque Country, you are becoming part of that heritage as well.

Itxaso: Yes.

Gretchen: It’s an interesting example of how economic and social and cultural things can really work together for something, like, being able to get a job doing something can allow you to fall in love with it.

Itxaso: Yes, yes.

Gretchen: Or it can be hard to stay in love with something if there’s no way to support yourself while doing it.

Itxaso: Absolutely. I remember that he was always invested in these processes. I have to admit that – now I’m gonna be a little picky again because these ideologies sometimes don’t always fully go – you know, we still have these biases – my dad’s fluency and also competency became stronger and stronger, and then he started to also speak like locals, little by little.

Gretchen: Okay, you know, this standard, unified Basque – he’s like, “Well, maybe I’ll talk like the other local people.”

Itxaso: I remember that my mom was very clear, especially in the beginning – I dunno if she feels that way anymore – that the standard is the correct one. I don’t think my dad did have so many overt ideas about it. For him, in the beginning, it was instrumental, “It’s gonna give me a good job,” and then he fell in love. And then it’s like, “Now, I have to go to the richness” – sometimes he would say that – “of the dialects of the traditions.” But he didn’t have this heritage Basque. He was born in rural Spain, and his parents moved to the Basque Country for economic reasons.

Gretchen: And he sort of fell in love with it anyway. What’s it like for you – because you live in the US now – doing research with Basque and trying to stay in touch with your Basque identity despite not living in the Basque Country?

Itxaso: For me, I have to admit that, again, I came to the United States thinking that I’m going to be an English teacher when I come back. I said, “I’m gonna do my master’s, and then I’m gonna go back to the Basque Country, and I’m gonna teach English.” Uh-uh, no.

Gretchen: Okay.

Itxaso: I realised that the farther I am from home, the more I wanted to understand the processes or how I felt as a kid because I realised, “Wait a minute, I can find answers to the shame and pride that I had growing up.” I was also ashamed of my grandparents that they didn’t know Basque because when he would take me to the park, right, I knew that people would talk with him. I would just go, instead of him looking at me whether I am falling off from the swing, I was checking on him to see who was gonna talk with him because I was ready to do the translation work for him.

Gretchen: Oh, okay, if he can’t talk to the other parents or grandparents or whatever, then you’re like, “Oh, here, Grandad, let me translate for you.”

Itxaso: Yep. Then I remember that I’d think, “Hey, I’m teaching him Basque. He’s practicing, right?” Every Sunday he would come, you know, to our hometown and, before going to the park, I made him study Basque. He was so bad at it. Like, terrible at it. It was very hard for him, and he would tell me, “But Itxaso, why are you doing this to me? I didn’t even go to school.” I mean, he didn’t have much schooling even in Spanish. I said, “Don’t worry. If you’re Basque, you have to speak Basque.” Those were some of the – and I was 5 or 6. I was so happy, right. At the same time, I had this very strong attachment to him but also internalised shame that in my family intergenerational transmission was stopped. As a 5-year-old kid, you don’t understand civil war – yet. [Laughter]

Gretchen: I hope not.

Itxaso: When I went to graduate school, I realised, “Wait a minute, my teachers were correcting me all the time.” I had this internalised shame that exercised, right. I was told that sometimes I wasn’t Basque enough; sometimes I was being seen as a real Basque. So, what’s happening? This is when I realised that sociolinguistics, which is the field of study that I do, became very therapeutical to me.

Gretchen: You can work through your issues or your family issues and your language issues by giving them names and connecting them with other people who’ve had similar experiences like, “Oh, I’m not alone in having this shame and these feelings.”

Itxaso: Absolutely. And that there were many of us. There were a lot of Spanish speakers in my classroom who, maybe they didn’t have literacy in Spanish, or they had similar encounters of feelings, and I said, “Wait a minute, so we’re not that weird,” and understanding that, in fact, this is quite common. Or there were also speakers of other language revitalisation contexts that I thought, “Oh, wait a minute, I thought we were this isolate case,” and you’re thinking, “No, we have similar feelings of inadequacy, but at the same time, pride.” I used the world of linguistics in general to understand these patterns and also to heal in some way.

Gretchen: No, it’s important.

Itxaso: I almost had a little bit of a rebel attitude in some ways. For me, it was like, “Ha ha! I got you now!”

Gretchen: Like, “You don’t need to make me feel shame anymore because I have linguistics to fight you with!”

Itxaso: There we go! “And now, I’m gonna go back with my dissertation. I’m gonna make sure that you understand that YOU are the one wrong and not me, and that when you correct me, I am also judging you.”

Gretchen: Does it work very well to show people your dissertation and tell them that they’re wrong?

Itxaso: No. [Laughter] Absolutely not.

Gretchen: I was gonna say, if you said this was working, it’s like, “Wow! You’re the first person that I know who wrote a dissertation and everyone admitted that they were wrong.”

Itxaso: Yeah, but then you have this hope.

Gretchen: Yeah.

Itxaso: Then I realised, okay, well, this is my therapeutic portfolio, basically.

Gretchen: At least you know in your heart that you are valid. So, you don’t like the word “heritage speaker,” which I think “heritage speaker” does work for – we don’t wanna say, “No one is a heritage speaker” – but for you in your context, that doesn’t feel like it resonates with you. What is a term that resonates with you for your context?

Itxaso: For me, it resonates more – I consider myself a native speaker of Basque, or my first language is definitely Basque. We have a term for that in the Basque Country, “euskaldun zahar,” and it literally means – “euskal” means “Basque,” “dun” means that you have it, and “zahar” means “old.”

Gretchen: You have the “Old Basque.”

Itxaso: Yeah, you have the Old Basque, which is associated with the dialects or the regional varieties. It has nothing to do with age.

Gretchen: Okay. You’re not an old Basque speaker as in you’re a senior citizen with grey hair, you’re a speaker of Old Basque.”

Itxaso: Mm-hmm.

Gretchen: Compared to a “New Basque” speaker?

Itxaso: There we go. Mm-hmm. A New Basque speaker, right, which we also have a Basque term for that, right, it actually means that you started it in more new times, which for us is associated with the revitalisation.

Gretchen: That’s like your parents.

Itxaso: Exactly. My parents consider themselves “new” speakers of Basque, and the Basque word for that is “euskaldun berri.”

Gretchen: “euskaldun berri.” So, this is “speaker of New Basque” or – and the idea of someone being a new speaker of a revitalised language in general where you learned it in adulthood and maybe you’re trying to pass it onto your kids and give them the opportunities they didn’t have, but you have these challenges that are unique to new speakers.

Itxaso: Absolutely. And oftentimes has to do with the idea of how authentic you are. This is something that is being negotiated, right – these negotiations we’re having in our household. When my mom said, “I know the correct Basque,” and I would basically implicitly tell her, when I was telling her, “But I know the authentic one.” Because of that, those similarly wider ideologies, right, this is how my parents also, little by little, they were able to sprinkle their Standard Basque with some regional “flavour,” as we call it, right. They would change their verbs, and they would start sounding more like the regional dialects.

Gretchen: Are there different contexts in which people tend to use the Standard Basque versus the older Basque varieties, like either formal or informal contexts, writing, speaking, like, official contexts or intimate contexts? Are there some differences, sociolinguistically, in terms of how they get used?

Itxaso: Yeah. For somebody that, for instance, I consider myself also bi-dialectal in Basque in the sense that I speak the regional variety now even if my first variety was actually the standard. I use the Standard Basque to write. But that is only part of the mess or the beauty or the complexification because those people that started learning Standard Basque in the school, sometimes, they might feel that their standard is too rigid to be able to have these informal conversations. One of the things that a lot of new speakers of Basque are doing is, in fact, creating language.

Gretchen: To create an informal version of the standard. Because it’s one thing to speak it in a classroom or something, but if you’re going to go marry someone and raise children in this and you wanna be able to have arguments or tell someone you love them or this sort of stuff maybe this thing that’s very classroom associated is too fancy-feeling for that context.

Itxaso: The same way that they don’t wanna sound like the kids in the cartoons, like Doraemon, for instance. [Laughter]

Gretchen: That’s not how real people sound.

Itxaso: Knowing that a standard was necessary for our survival, for the language to survive, at least during those times, but at the same time, we need to get out of this rigidity that this standard might give us. The new speakers in many ways are the engineers of the language.

Gretchen: The original creation of Standard Basque in the 1980s was taking from all of these different regional varieties and coming up with a version that could be written, and you could have one Basque curriculum that all of the schools could use rather than each region trying to come up with its own curriculum, which is logistically challenging.

Itxaso: Absolutely. The Standard Basque was created, finally, in 1968, and little by little being introduced in the educational purposes. And the education in the ’80s, too, is when [exploding noise] bilingual schools skyrocketed, and the immersion programme became the most common one.

Gretchen: And this is immersion for kids, for adults, for everybody?

Itxaso: For kids. You start with kindergarten or, I dunno the terms here in the US, but 2- or 3-years-old, all throughout university. Of course, that went through different stages. Of course, there’s some degrees in university that might not be fully taught in Basque, but overall, little by little, I mean, in the past four years, a lot of that has been done.

Gretchen: What’s it like for you now going back to the Basque Country being like, “Wow, revitalisation is done. It’s complete. Everything is accomplished. We have nothing to worry about anymore.” Is this the case?

Itxaso: Absolutely not. There’s still debates going on. One of the big debates that have been talked – so we have sociolinguistic surveys that we wanna measure how successful is this standard, and what does that even mean. All the people who learned Basque in the schools, like my parents, are they actually using the language all the time? Or even if you grew up speaking Basque. The reality is that Basque revitalisation has been very successful in creating bilinguals. Most of the population, if you are 40 or younger – especially here I’m talking about the Basque Country in the Spanish side because the French side does not have the same governmental support that we do. The answer is that some surveys show that Basque is not as spoken as it is acquired.

Gretchen: People learn it in the schools in the immersion programmes, but then, the kids are playing on the playground, maybe they’re not using it as much, or you’re going into a store, and you’re buying some milk or something, and you’re not necessarily using Basque for these day-to-day interactions.

Itxaso: Correct. I remember when I was doing my own fieldwork and collecting data for my dissertation, I remember that I would ask people from the city because this is where the revitalisation was most impactful because this is where Basque was least spoken before the standard was implemented. That was a – oh, my goodness. There is this saying that we have that Basque is being used with children and dogs.

Gretchen: Okay. [Laughter]

Itxaso: And then I started to notice – and, you know, my sister, she uses Basque with her friends, but at home, she would use a lot of Basque with the dog that she got a few years ago. I was so surprised because then our interactions back home become more Spanish-dominant with time. I was like, “Oh, my goodness. Is this true?” I started to notice. In fact, some adults that would talk Basque to their children but also to the dogs, but later on, a lot of the adult interactions.

Gretchen: But then when you grow up, you use Spanish. You have this ideology of “Okay, well, it’s important for children to have Basque, but then you grow up and you put it away,” which doesn’t sound that great.

Itxaso: Meaning that the normalisation of Basque, it hasn’t started.

Gretchen: It has succeeded at some level, yeah.

Itxaso: Absolutely. But the work is not completely done yet. I don’t think it’s ever gonna be – I mean, when I say it’s never gonna done meaning that you always have new processes or new challenges. One thing that I did notice – so the last sociolinguistics survey showed two very interesting trends in the opposite direction. The first one was that new speakers, and especially young new speakers from the city, they’re starting to embrace Basque in their daily life interactions. They’re adopting the language and using it and engineering it and making it more informal. In fact, we have different standard Basques that are starting to emerge in one city, in Bilbao. Another one might be emerging in Vitoria-Gasteiz, which is the capital. And the other one – San Sebastián. There’s still a standard but with some flavours. People are documenting that. The other one is that in certain Basque-speaking regions or traditional speaking regions like my hometown, for instance, that the use of Basque among teenagers has actually dropped a little bit – slightly. I have noticed that, too, when I go back. I was thinking, “Why would that be? Why is it that teenagers might see” –

Gretchen: You have to think that Basque is cool as a teenager.

Itxaso: Exactly. I also noticed different kinds of trends. When I grew up in the ’90s, during my rebel times, we loved punk. We loved rock.

Gretchen: Was there Basque music in rock and punk and this sort of stuff?

Itxaso: Oh, my goodness, Berri Txarrak, which translates to “bad news.”

Gretchen: We should link to some Basque music in the shownotes so people can listen to it if they want.

Itxaso: We loved it. Little by little, more soft rock became more popular. This is still popular. But I noticed in the past five years or so that reggaetón is –

Gretchen: The young people are listening to reggaetón. Is there reggaetón in Basque?

Itxaso: That’s what we need, I think.

Gretchen: Okay. If there’re any reggaetón artists who are listening to this, and you speak Basque, this is your project.

Itxaso: I’m like – maybe there is. I’m not a big fan of reggaetón.

Gretchen: But it’s what the young people want. It’s not about you anymore.

Itxaso: Exactly. I do wanna hear some Basque – I know there is feminist reggaetón, but I haven’t heard Basque reggaetón as much.

Gretchen: Maybe someone will tell us about it.

Itxaso: Maybe it’s time to adjust to –

Gretchen: And to keep adapting because it’s not just like, “Oh, we have this one vision of what Basque culture looked like in the past, and you have to be connected to that thing specifically,” it’s that it evolves because it’s a living culture with what else is going on in the world.

Itxaso: Absolutely. This is where the making of what it means to be a speaker of a minority language also comes into play. I know that in many Indigenous language revitalisation processes hip hop music has been extremely important in the process of language revitalisation. Maybe we do need some Basque reggaetón.

Gretchen: All right. Sounds good. I’m sold. Basque is famous among linguists as being a language that’s spoken in Europe but that’s not ancestrally related to any of the other Indo-European languages. This makes it famous, but also, I dunno, how does this make you feel?

Itxaso: Aye yae yae yae yae. It makes me feel good and bad at the same time because it’s like, “Oh, you know about Basque? That’s awesome!”, but then, “Oh, we’re being told that this is what you know about Basque,” which is this “exotic” language, and I’m like, “No, no.” That’s the part that I’m like, “No, we’re normal, too.”

Gretchen: “We’re also just people who’re speaking a language trying to go about our lives.” It also has things that are in common with other language revitalisation contexts – I’m thinking of Gaelic and Irish in Scotland and Ireland and lots of Indigenous language contexts in the Americas, in Australia. There’s so many different places where there’s a language that’s been oppressed, and it’s hard to say what is Indigenous in the Spain-France context, but definitely big governments have said, “Oh, you should all be speaking Spanish,” “You should all be speaking French,” and you have to struggle to make this something that is recognised and funded and important and prestigious and all of this stuff.

Itxaso: Absolutely. And for the first time in the history of the Basque language, now we are considered a “modern” language – another stereotype that oftentimes – “Oh, you are such an old language!” And I’m thinking, “But we speak it today.”

Gretchen: It’s not only ancient speakers. There’s still modern people speaking Basque.

Itxaso: Yes, and we have a future. We can do Twitter. We can do Facebook. We can do social media.

Gretchen: You can do Reggaetón.

Itxaso: Reggaetón in Basque. We can do a lot of things in Basque. People associate us oftentimes with these ancient times from the lands of the Pyrenees and caves. I’m like, “Great.”

Gretchen: But you’re not living in caves now.

Itxaso: Exactly. And when they tell us, “Oh, you are this unique language and so weird,” and I’m like, “We’re not weird. We’re unique like any other language, but we also have similar processes.”

Gretchen: Ultimately, every language is descended from – like, languages are always created in contact with other people, so there’s this ancestral descendant from whatever people were speaking 100,000 years ago that we have no records of. Everything is ultimately connected to all of the other humans, even if we aren’t capable of currently tracing those relationships with what we have access to right now.

Itxaso: Even within among linguists, right, it has been debated – Basque has been compared to possibly every language family out there. Even Basque people, “Oh, we found a connection! Maybe we are connected to the languages of the Caucasus.” All Basque linguists just roll their eyes thinking, “Here we go again.”

Gretchen: “Here’s another one.”

Itxaso: This idea of also looking at the past has been very important to understand our existence, but also it’s important to understand that we have a future, and that one is going to form the other in many ways. When they say, “Oh, where is Basque coming from?”, I’m like, “I dunno if we’re ever gonna find that out.”

Gretchen: I dunno if that’s the most interesting question that we could be asking because it’s hard to have fossils of a language. Writing systems only go back so far, and the languages being spoken and signed much, much earlier than that, we just don’t know because they don’t leave physical traces in the air.

Itxaso: What is fascinating is that, so recently, there has been some evidence – they found some remains that, in fact, Basque was written before the standard or before when we thought. Initially, we know that the first Basque writings were names in tombs, in graveyards. Now, we actually have some evidence – or at least they found some evidence – that Basque might have been used for written purposes also and that the Iberian writing system was used for that. They’re still trying to decode.

Gretchen: Maybe we could link to a little bit of what that looks like if there’s some of that online, too.

Itxaso: It looks like a hand. The text looks like a hand, and there’re five words there. They have only been able to decode one word.

Gretchen: But they think that word is Basque?

Itxaso: Yes.

Gretchen: Cool.

Itxaso: We will see. I mean, stay tuned.

Gretchen: Further adventures in Basque archaeology, yeah.

Itxaso: Even for Basque people that is actually really exciting. That’s where the part of like, “Oh, maybe we know where we come from!” We’re like, “We actually come from maybe there,” or I dunno, does that make my dad less Basque for that?

Gretchen: And does that make the new speakers less valid? But it’s still kind of cool to find out about your history.

Itxaso: Yes, and that this history’s so complex. It’s also entrenched in our real life today. It’s still important to us in some ways.

Gretchen: You also co-wrote a paper that I think has a really great title, and I’d love you to tell me about the contents of the paper as well. It has a very interesting topic. It’s called, “Bilingualism with minority languages: Why searching for unicorn language users does not move us forward.” What do you mean by a “unicorn language user”?

Itxaso: Well, first of all, I have to admit that this title was by the first author, Evelina. I mean, amazing. What we mean by “unicorn language users” is that when we study languages, or when we think of people who speak languages, there is that stereotypical image that comes to our mind, and it oftentimes has to be, “Oh, maybe a fluent speaker or a native speaker.” But what does that even mean in a minority language context where language transmission has been stopped and then back regained in a completely different way? Then you also have these ways of thinking from the past intermingled with the modern reality. Who is a Basque speaker?

Gretchen: Right. Is it true that basically every Basque speaker at this point is bilingual?

Itxaso: Absolutely. When you do research with Basque, and with many minority languages, you have to do it in a multilingual way of thinking because if there is a minority, it’s for a reason.

Gretchen: You can’t find this unicorn Basque speaker who’s a monolingual you can compare to your unicorn Spanish monolingual – well, there are Spanish monolingual speakers – but trying to have this direct comparison is not something that’s gonna be realistic. Your co-authors of this paper are speakers of Galician and Catalan –

Itxaso: Also, Greek.

Gretchen: And also, Greek!

Itxaso: Cypriot Greek.

Gretchen: Cypriot Greek – who have had similar experiences with being – we’re not saying “heritage speakers” – but being speakers that have connected to multiple bilingual experiences.

Itxaso: Minorities, right. It all unites us because all of us had some experience that was within Spain. Either we grew up or we live in the nation state of Spain. What was interesting is that, as we were discussing this paper, all of us had slightly different experiences as users of minority languages. In Catalan or in Galician or Basque and also Cypriot Greek. I said, “How can we understand all of these complex or slightly different ways of experiencing” – and our experiences have also changed throughout our lives. How is it that we use the language – what associations we have, what the language means to us, or the languages mean to us, what kind of multi-lingual practices we actually engage in. At the same time, I remember that in the paper we also reflected a little bit on how we also engaged in our research in these unicorn searches in the beginning and how to unlearn that.

Gretchen: Because when you’re first trying to write a paper about Basque, and you’re saying, “Okay, I’m gonna interview these Basque speakers, and I’ve got to find people who are the closest to monolingual that I can,” or who embody these sort of, “They learned this language before a certain age,” because your professors or the reviewers for the paper or the journals – what you think people want or these studies that you’ve been exposed to already have this very specific idea of what a speaker is or a language user – because we wanna include signers and stuff as well – what exactly someone is to know a language compared to the reality of what’s going on on the ground which is much more complex than that.

Itxaso: Absolutely. I feel like we have to self-reflect onto how is it that we’re representing and doing research – or the issue of representation becomes really, really, really important. What is it that we’re describing, what is it that we’re explaining, how are we doing it. Sometimes, there’re power dynamics within this knowledge in the field. When you wanna publish a paper in a top journal, there’s certain practices.

Gretchen: And they wanna have a monolingual control group. “Oh, you’ve got to compare everything to English speakers or to Spanish speakers because they’re big languages we’ve heard of.” Like, “Can’t I just write about Basque because there’re lots of papers that are only about English or only about Spanish? Why can’t there be papers only about Basque?”

Itxaso: Exactly. And you are thinking, “Wait a minute, I can’t find a Basque monolingual.” Maybe they exist, but they’re not readily, either, available, or it’s not common –

Gretchen: In a cave somewhere.

Itxaso: Right. We’re like, “Okay, well” – exactly. Or maybe they do live monolingually.

Gretchen: Yeah, but they still have some exposure to Spanish even though most of their life they’re in Basque. And going and finding this 1% of speakers who managed to live this monolingual life – how well is that really representing a typical Basque experience or a breadth of experiences with the language, which, most of which have some level of multilingualism?

Itxaso: Correct. We as researchers sometimes have to pick. When we make those decisions, we sometimes do not make those decisions consciously because a lot of those questions might come from the field. But then this paper also allowed us to reflect on also thinking, “Why is it that I have to put up with this? This is not working properly and describing things that matter to us” – and matter to us as a community, not only as researchers. Why is it that my parents’ varieties do not get represented that well? Why is it that other participants do not make it to the experiment because they get excluded on the basis of just, oh, literacy, and things like that, which becomes a sticking point as well. Who is a unicorn? Well, clearly there are no unicorns. There are many unicorns.

Gretchen: Sometimes, I think that there’s an idea that being, say, a bilingual speaker is like being two monolingual speakers in a trench coat. The thing that you’re looking for, this unicorn-balanced bilingual of someone who uses their languages in all contexts and is completely “fluent” – whatever we mean by that – in all contexts when, in reality, many people who live bilingual or multilingual lives have some language they use with their family or some language they use at the workplace or in public or that they’re reading more or that they’re consuming media in more. They have different contexts in which they use different languages.

Itxaso: Compartmentalisation is very important but not full compartmentalisation either. There’s gonna be a lot of different overlaps – and so many different experiences. Another thing is that I think doing research with new speakers is important is because those experiences may change from year to year.

Gretchen: Your parents’ cohort of new speakers compared to new speakers who are teenagers now – they’re gonna have very different experiences.

Itxaso: Or maybe a new speaker when they are teenagers versus when they’re in the labour market versus when –

Gretchen: They’re having kids or they’re grandparents or something are gonna have very different experiences even throughout the course of their lives.

Itxaso: Even myself, me as a Basque speaker, my way of speaking has also changed or the way I adapt. One of the challenges in the Basque Country has been “What are the processes – or how is it that they decide, ‘I’m gonna speak the language’?” It’s a continuation. This adoption of the language, you don’t fully, suddenly adopt it.

Gretchen: You don’t adopt it and then that’s all, you’re only speaking Basque from now on. It’s a decision that you’re making every day, “Am I gonna speak Basque in this context? Am I gonna keep using it?”

Itxaso: You negotiate that because, obviously, when you speak a minority language, you’re gonna be reminded that certain challenges might come on the way. Some new speakers might like to be corrected, but some might not.

Gretchen: So, how do you negotiate “Are you gonna correct this person?” “Are you not gonna correct this person?” “Can you ask for correction?” What do you want out of that situation?

Itxaso: Some new speakers, they might want to also sound like regional dialects or older dialects, but some others might not. They create other ways to authenticate themselves and to invest in the language and to invest in the practices that come with it. Each person is unique at the individual level, but then at the collective level, things happen, too. Understanding those is very, very, very, very important.

Gretchen: The balance between the language in an individual and also a language in the community or in a collective group of people who know a language – both of those things existing. We’ve talked a lot about new speakers of Basque. Are there also heritage speakers in the Basque context?

Itxaso: There are. In fact, they do exist. The question is, “Who would these people be?” These people could actually be people that grew up speaking Basque at home but maybe, during the dictatorship, they didn’t have access to the schooling in Basque, so they might not have literacy skills in Basque – so older generations.

Gretchen: They might have things that are in common with heritage speakers. The way that I’ve heard “heritage speakers” get talked about in the Canadian or North American context is often through immigrants. Your parents immigrate from somewhere, and then the kids grow up speaking the parents’ language but also the broader community language and that parents’ language as a heritage language. That still happens in Basque; it’s just that wasn’t your experience in Basque, so you wanna have a distinction between heritage and new speakers.

Itxaso: It’s also true that sometimes if we focus too much on the new speakers, we actually also forget describing the experiences of these individuals that we might consider from the literature as heritage speakers because they don’t use this term for themselves.

Gretchen: The heritage speakers don’t use it for themselves?

Itxaso: Yeah. Or the Basque people that say, “I am just a Basque speaker” or a “traditional Basque speaker” but in a different way. They usually say, “But I don’t do the standard.”

Gretchen: “I’m not very good.”

Itxaso: Sometimes, they think that their Basque is not good enough because they don’t have that literacy.

Gretchen: Or they might be able to understand more than they can talk, sometimes happens to people.

Itxaso: Yeah, sometimes it can happen. Or they talk very fluently, but then they say, “I don’t understand the news,” because they’re in the Standard.

Gretchen: Finally, if you could leave people knowing one thing about linguistics, whether Basque-specific or not, what would that be?

Itxaso: I think that – oof, that’s a loaded question, I love it. For me, I would say linguistics is rebellion. Linguistics is therapy. Linguistics is healing. A linguist is the future. [Laughs] And minority languages have a lot to show about that. In this case, it’s Basque – or for me it’s Basque because I’m intimately related to Basque – but those are the key aspects that I would say that you can do therapy through linguistics.

Gretchen: Linguistics is therapy. Linguistics is rebellion. I love it. That’s so great.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr. You can get bouba and kiki scarves, posters with our aesthetic redesign of the International Phonetic Alphabet on them, t-shirts that say, “Etymology isn’t Destiny,” and other Lingthusiasm merch at lingthusiasm.com/merch. I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet. Lauren tweets and blogs as Superlinguo. Our guest, Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez, can be found at BasqueUIUC.wordpress.com. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include a behind-the-scenes interview with Lingthusiasm team member, Martha Tsutsui-Billins, a recap about linguistics institutes, a.k.a., linguist summer camps, and a linguistics advice episode. Also, if you like Lingthusiasm but wish it would help put you to sleep better, we also have a very special Lingthusiasmr bonus episode [ASMR voice] where we read some linguistics stimulus sentences to you in a calm, soothing voice. [Regular voice] Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language. Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Itxaso: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#language#linguists#lingthusiasm#podcasts#episode 86#transcripts#interviews#basque#language revitalization#transcript#language acquisition#language ideology#standard language ideology

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

pro tip: you wanna learn a new language (french, Italian, Spanish, English, Portuguese, etc.)? learn latin first, its a dead language however you pick up tiny things that are easy to miss. for example in kréyol happy is kontant which sounds a lot like content in English which stems from the latin word contentus meaning satisfied. i love when languages do the thing

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

good news lads i'm sooo good at making french sound like not-english that zoom now asks me if i want to switch my language when i start talking in french class. i closed the pop-up too fast to actually read it but i don't think it was asking if i wanted to switch my language to french specifically, it was just like hm i do not think that is english. but whatever my ego will take it!!!

#the two important phases of learning to speak french are 1) speak something that non-francophones think is not english#2) speak something that francophones think is french#i've got phase one down! watch out world!!!#it's like woah i do not know what you are saying but i DO know that that is NOT english.#ok great! that's what i was going for!! (kind of lol)#language acquisition

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

i just studied french for 2 hours so of course a korean song from 2010 is what's popped into my head now

why am i like this

#i learned korean from 2010-2015 (self taught primarily and then one year of formal class)#french#foreign language#langblr#language acquisition#always mixing up languages dammit#multilingual#korean#gemplans#studyblr#french studyblr#korean studyblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The difference between あのー and えーっと

As I touched on in my japanese goncharov post, it’s amazing how much novel research, entertainment, and art are locked behind a language barrier. Even though as english speakers, we are privileged to have many things translated into our language, it’s a simple fact that most things will not be translated into most languages.

I am a huge fan of ゆる言語学ラジオ, a japanese podcast about linguistics. The hosts recently released a book, 言語沼, which goes into detail about some of the subconscious rules native japanese speakers follow but aren’t consciously aware of (an english equivalent might be that adjective-ordering rule we follow e.g. big brown cow, not brown big cow). I’m finding it fascinating, and I wanted to discuss some of it here in english, because I think people learning japanese would find some of these things really useful. It’d be a shame if this knowledge stayed stuck behind the japanese language barrier when the people who would find it the most useful can’t speak japanese fluently enough to read it!

The book talks about how most Japanese people will think of 「あのー」 and 「えーっと」 as having the exact same meaning - they’re both “meaningless” filler words. Despite their belief that they’re the same, those same native speakers will subconsciously only use あのー in one particular type of situation and 「えーっと」 in another, and even feel confused or annoyed if they hear another speaker use one in the wrong context.

So what’s the actual difference? 「えーっと」 is used when the speaker is taking time to remember or solve something. For example, the following exchange is very natural:

Person A: 7 x 5は?

Person B: えーっと、35だ

This makes it a pretty versatile filler word! You can use it pretty much anywhere. Another example would be when you’re talking to yourself, trying to remember where you left your keys.

えーっと、鍵どこ置いたっけ?

On the other hand, あのー is much more specific. It can only be used when you’re taking time to figure out the best way to phrase something. For example, when you’re trying to get a stranger’s attention.

あのー、ちょっといいですか?

In contrast, if Person A was addressed with 「えーっと、ちょっといいですか?」by Person B, they’d feel it was rude because instead of considering how to say something, B is considering what to say, which gives the impression that they hadn’t even figured out what they needed to ask before addressing Person A.

This gives 「あのー」 a more ”polite” feeling than 「えーっと」, even though neither is actually more polite than the other. They’re just used in different circumstances.

Let’s quickly look at the example with the lost keys again. If you replace the filler word:

あのー、鍵どこ置いたっけ?

It is very unnatural. The authors of the book jokingly say that it sounds like you’re talking to a ghost, because 「あのー」 is only used when you’re figuring out how to phrase something, and you wouldn’t worry about that if you’re talking to yourself.

Also, did you know even japanese children properly use each filler word in the correct situation? Despite almost all japanese people (even as adults) being unaware of this rule, they’re subconsciously abiding by it even as children - just from listening to their parents follow the same rules!

It really is amazing how good your subconscious mind is at acquiring language, and how terrible your conscious mind is at it. If you’re not already, I highly recommend integrating a lot of simple language content (e.g. youtube, kids shows, etc) into your study routine - listening to people talk is simply the fastest way to become fluent in your target language.

#langblr#japanese#language learning#language acquisition#japanese language#language#linguistics#learning japanese#japanese grammar#jimmy blogthong

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

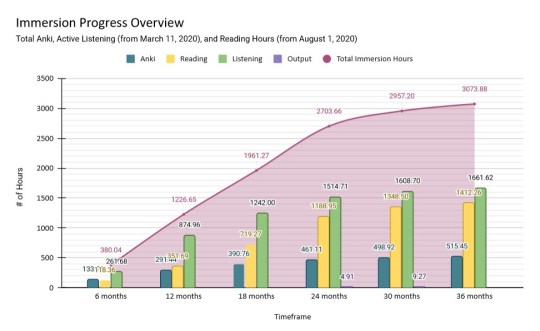

Today is my 3rd year of learning Japanese through immersion!

For the most part, I was just in maintenance mode as I tried to take care of myself and reassess my goals. Basically, I went through a lot of burnout when I realized I couldn't really make a career with my pursuit of fluency in this language. I then tried to pursue baking and started a small business which was fun, but ultimately wasn't very profitable because of how expensive the ingredients are. I made another career change which has been fulfilling so far because of how nice and helpful everyone is around me, the only drawback being that it's on a graveyard shift, which makes it difficult to immerse when I feel sleepy during the afternoons when I finally wake up.

I think a lot of things in my life changed for the better tho, and I'm still grateful for a lot of people in this community who continue to inspire me to pursue great things and to keep going despite everything crazy going on.

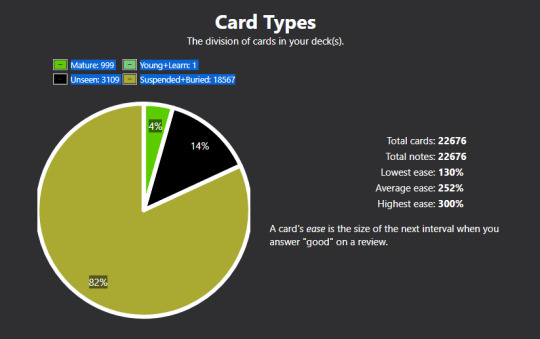

I still am doing daily Anki reviews and currently have 19,567 learned words in my deck now, most of which I've decided to suspend because a lot of them were way past the 1-year interval. I also feel the need to "refresh" and "start from scratch" by basically doing all new cards once I find a schedule that allows me to immerse again. I haven't studied many new cards either and have just been waiting to mature all of my cards so I can suspend them in preparation for the refresh I'm hoping for.

I also thought that because I barely spent time with the language I would just forget all of it, but to my surprise, any time I pick up something to read or watch a drama or an anime episode, I could still understand a lot of what was going on (with some Yomichan cope of course, lol). I'm not sure if that's because I had already put in 3000+ hours in the language before I finally decided to take a huge break from it, but nonetheless, I'm glad I don't have to do much in terms of getting back on track whenever I feel like dedicating time to it again.

That's it for my little update. Hopefully, a fresh start and some really interesting content can get me back into reading and watching. I still love this language and I don't think at this point I can ever unlearn it.

Thanks as always, and I hope to update you soon. ʕ•̀ω•́ʔ✧

#language immersion#japanese language#language learning#language acquisition#japanese#studyblr#langblr#japanese langblr

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reference for anyone writing children - when my daughter was 20 months old (just over a year and a half), here were her words. Kids usually have a language jump around 20 months. I compiled the list over a few days.

She didn’t really make sentences beyond “I want X/I see X” and generally a lot of pointing was involved.

Book

Bead

Bag

Whee

Challah

Hi, hello

Bye

See ya

Ball

Awoooooo (wolf)

Owl

Qua-qua (duck)

Elpha (elephant)

Wa-wa (water)

My-my (milk)

Boob

Mine

Dada

Mama

Owie

Sister

Anna

AHDDA (any Disney princess)

Bella

Hat

Shoes

Boots

Grrr

Sipsy (Itsy Bitsy spider)

Ish (fish)

Up

UP (down)

Uppie (carry me)

Uh-huh, mm-hm (yes)

Uh-uh (no)

Chair

Sit

Me (aka follow me)

Elma (Elmo)

I see X

I want X

Yeah

Shpsh (super girl flying sfx)

Hi-ya (sword fighting sfx)

Baby

Please

Just one year later - at 2.5yo - she was trying to explain what snack she wanted. She described it as "the food I want to put in my mouth that is in that cabinet that is a circle with a strawberry on it.”

It was Strawberry Pocky.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will not type up multiple paragraphs in response to a rhetorical question just because it’s about language acquisition.

I will not type up multiple paragraphs in response to a rhetorical question just because it’s about language acquisition.

I will not type up multiple paragraphs in response to a rhetorical question just because it’s about language acquisition.

I will not type up multiple paragraphs in response to a rhetorical question just because it’s about language acquisition.

19 notes

·

View notes