#it's sketches from araki edited together

Text

K O I C H I

#JJBA#it's sketches from araki edited together#he made koichi a creature first#jojo's bizarre adventure#diamond is unbreakable#it's new stuff for once#josuke higashikata#okuyasu nijimura#koichi hirose#lolo edits#jojo meme#duwang gang

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

LGBTQI & BIPOC Representation In Media

With creative editing and filming, I believe that any type of style can be achieved visually. But the interpretation of a particular style of cinematography really depends on the person filming or editing. More importantly is the viewers perception. Outstanding filmmakers and editors find ways to create a film where viewers get the message or feeling they set out to deliver. I’ll compare achieving a visual style to my world of art. When an artist does a sketch or paints a picture, they do their best to depict their message through their art. But each person translates that message of artwork differently. Just walk around an art museum such as MoMA with a group of people and I guarantee each person will have a different view of each piece of art. This goes the same for films. Films have a different impact on each viewer, but the ultimate goal is for the filmmaker to get their message through. I’ll admit, “queer cinema,” is something I never thought about or analyzed. I did some research online to get a better understanding of this style of cinematography. According to Todd Haynes, “New Queer Cinema produced complex work that didn't simply create new gay heroes as subjects. It dealt with the politics of representation, it ventured into transgressive themes [and] challenged simple ideas about victimhood and subjugation” (Green, 2016).

In order to understand how I came up with answers to the questions for this blog, I think it’s important that I list the films we were assigned to watch. There were five films in all: Mysterious Skin by Gregg Araki, Boy’s Don’t Cry by Kimberly Peirce, Moonlight by Barry Jenkins, Call Me By Your Name by Luca Guadagnino, and Brokeback Mountain by Ang Lee.

(Jenkins, Moonlight)

I think “queer cinema” is a visual style that is secretive, as in most of the films we watched for this blog. A secretive style can be dark or isolated. In Moonlight at 51m:20s-55m:50s when Chiron and Kevin are sitting on the beach in the moonlight is a safe place for them to be together. The darkness is the only time of day that Chiron can be himself. Oliver and Elio secretly persued their gay relationship in the secluded countryside of Italy in Call Me By Your Name. There are many examples throughout this film, but one is at 1h:45m:50s when Oliver and Elio go on a hike. Another way to show a “queer cinema” style in film is through the editing. Scenes can be cut in a way where only enough information is shown, giving it a secretive style. And by secretive, I’m referring to the hidden lifestyle like we see between Ennis and Jack as they go drive out to the mountains to hide their affair (1h:09m:30s). Their relationships are hidden because depending on each person’s race or living environment, it conflicts with what is considered ‘normal’.

As we saw in most of these films, race, gender, and sexual identities visually intersected. In Moonlight, we saw a young black boy struggling with his gay sexuality in a high crime neighboorhood in Miami. Then in Call Me By Your Name, we saw a young, wealthy white man exploring his gay sexuality in the natural countryside of Italy. These are completely opposite films in terms of race and status, but both protagonists are gay men who struggle with being open about their sexuality.

While films can educate or empower people, and even make us change our perceptions, films can’t change someone’s sexuality. That’s like saying a film showing heterosexual relationships can make a gay person straight. Cinematography doesn’t sway or change one’s sexuality. But the message of these films might empower someone struggling with their sexuality to no longer hide it. Just as films can change an anti-LGBTQ’s perception about LGBTQ. Boys Don’t Cry was based on a true story about Brandon Teena. When movies are based on someone’s life, they have more of an affect on the audience. I found an article about Brandon Teena’s court case and the end of the article summed up the message of the film. The writer of the article reached out to the Sheriff’s Office that investigated Brandon’s case to ask if they would be willing to attend a LGBT-sensitivity training program. The current Sheriff asked what was the definition of a transgender person. “I struggled to define it, but I basically came to the conclusion that a transgender person is whatever they say they are. It's a simple concept—honoring however people want to define themselves—but it requires a leap of imagination Lotter, Nissen and [ex-Sheriff] Laux couldn't make—and it would have made all the difference” (Fairyington, 2018).

Speaking about messages from films, I was disgusted by how mistreated and abused by society LGBTQ people were. I was hoping society changed a lot since the time of these films but that’s not the case. According to a 2020 FBI Hate Crimes Report, “Today’s report shows that hate crimes based on sexual orientation represent 16.7% of hate crimes, the third largest category after race and religion” (Ronan, 2020). There’s still a lot of ignorance about LGBTQ. Boys Don’t Cry is a great example of a film that opened my eyes to how life was for a transgender female back in the 1990s in a small town in Nebraska. The minute Brandon’s secret was out that he was really a female (1h:13m:07s-1:13m:55s), two men who didn’t agree with his sexuality came up with a plan to beat and rape Brandon, then eventually kill him. In Moonlight, Chiron got the crap beat out of him (1h:01m:05s-1h:02m:00s) simply because he was gay. Mysterious Skin showed the horrifying world of a young boy who was sexually abused by his baseball coach. I’m still not sure if Neil was gay or if he knew no other form of sexuality because of being sexually abused at such a young age. Brokeback Mountain showed how forbidden being gay was for two cowboys out in Wyoming. And Call Me By Your Name was the only film out of the five that didn’t result in violence once others found out that Elio and Oliver had a relationship. In fact after Oliver left and broke Elio’s heart, his father told him, “You’re too smart not to know how special what you two had was…just remember I’m here” (1h:57m:30s- 2h:12m:00s). Even though Elio’s family was open to their son’s gay relationship, it was forbidden in Oliver’s world.

(Magan, 2019)

These films showed me how difficult it was (and still is) for someone who is LGBTQ to live a life without fear. These films are educational and eye-opening. If that was each filmmaker’s goal, then they all succeeded with me. I just hope each film’s message has a bigger impact on people with no compassion for LGBTQ’s.

My entry for a 5th grade diversity art contest, 2013. I purposely sketched this in black & white as a symbolism of equality.

0 notes

Photo

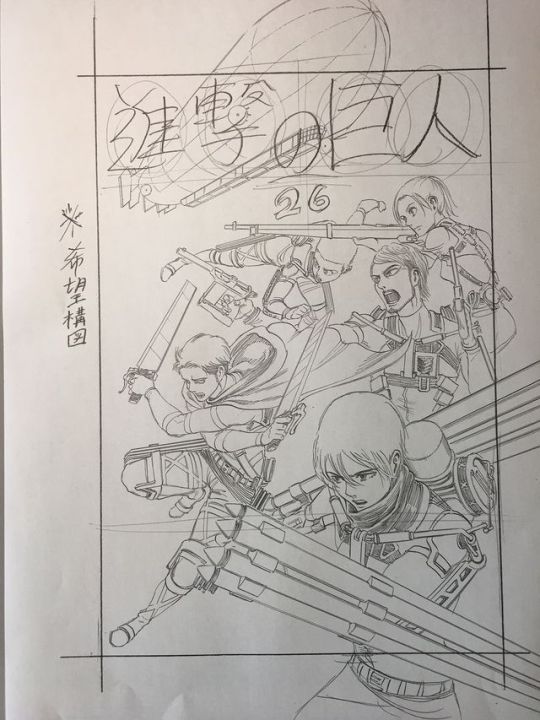

Isayama Hajime Shares New Blog Post with Original Sketch of Tankobon Vol. 26 Cover Illustration

After a nearly two-month hiatus, Isayama Hajime has finally shared a new blog post, where he included the original sketch of the cover of tankobon vol. 26 (Release date August 9th, 2018)!

His blog discusses his thoughts on season 3 of the anime. Please check back here for a translated summary!

Update (July 24th, 2018): Isayama wrote some very honest and emotional words for Season 3 that you can now read below!

Translation: @suniuz; Editing: @fuku-shuu

(Please credit/link back to this post if referenced or used!)

[T/N: Isayama first apologized for the lack of updates, as he hadn’t written in his blog in about two months]

“However! SnK Season 3!!! It was indeed wonderful!!

The moments around Volume 13-16 in the manga might be a result of my personal fallout after I finished drawing Volume 12. It felt like I was in a state when my energy/fuel was totally exhausted due to nothing but my own incompetence. Back then, I managed to somehow keep turning in the manuscripts, which I reluctantly extended and made duller each month.

At least, in my self-reflection I was weak-minded. Thus, when Season 3’s anime production first started, I discussed with the staff members and expressed that I hope they could appropriately rearrange the sections and functions of storylines in Volume 13-16 from the get-go.

As a result, they delivered an idealized script for me, and this time the story has a structure that I had no way of accomplishing with my own skills!

It was already in a good shape even during the first round of proofreading. Thanks to the talents of screenwriter Kobayashi Yasuko-san, she constructed a clear and succinct backbone for my messed up manga. Then, with his specialized expression of roughness and astringency, Seko Hiroshi-san turned some poorly-written plots in the original manga into more compelling forms.

In addition, thanks to Director Araki who brought together guidelines for the overall production, seiyuus who give life to the characters, as well as all members who participated in the production. This time, I can ascend to heaven right after I die!”

[T/N: Isayama then said he is going to watch the film One Cut of the Dead (Kameru o Tomeru na!), which his sister highly recommended.]

Related News: Isayama Hajime || Photos: Isayama Sketches || Season 3 || Translations: Other

Archival News: Isayama Hajime || Season 3

#snk news#isayama hajime#mikasa ackerman#levi ackerman#jean kirschtein#connie springer#sasha braus#snk merchandise#snk season 3#photos: isayama sketches#translations: other#snk staff#seko hiroshi#kobayashi yasuko

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (29): (1587) Third Month, the Last Day, Midday.

29) Third Month, Last Day; Midday¹.

◦ Two-mat room².

◦ [Guests:] Bungo Yoshimune [豊後義統]³, Tawara Yotsuo [田原四郎]⁴, Rōju [良壽]⁵.

Sho [初]⁶.

◦ Tōyo [東與]⁷.

◦ On an ō-ita [大板]⁸:

◦ yuen-buro [油煙風爐]⁹ ・ kama unryū [釜雲龍]¹⁰ ・ kan [クハン]¹¹ ・ habōki [羽帚]¹².

◦ On the tana:

◦ in a na-kago [菜籠], the charcoal¹³.

▵ Shiru hoshi-na sakura-gai [汁 干菜 ・ 櫻貝]¹⁴.

▵ Namasu [ナマス]¹⁵.

▵ Kamaboko ・ unagi [カマホコ ・ ウナキ]¹⁶.

▵ Ae-mono [アヘモノ]¹⁷.

▵ Senbei ・ iri-kaya ・ shiitake [センヘイ ・ イリカヤ ・ 椎茸]¹⁸.

Go [後]¹⁹.

◦ The [scroll in the] toko was rolled up²⁰; [in a] naga-fukube [長フクベ], flowers of the wisteria²¹.

◦ Ō-ita as before, hishaku [ヒシヤク] ・ futaoki hikkiri [蓋置 引切]²².

◦ Mizusashi imo-gashira [水指 芋カシラ]²³.

◦ Chaire Enza [茶入 圓座]²⁴.

◦ Chawan kuro [茶碗 黒]²⁵.

_________________________

¹San-gatsu misoka, hiru [三月晦日、晝].

Misoka [晦日] means the last day of the month (which, in this case, was the 30th day of the Third Month*). The date was May 7 in the Gregorian calendar.

While this chakai is included in both Shibayama Fugen’s and Tanaka Senshō’s commentaries, it is missing from the modern Japanese version edited by Kumakura Isao. As in the past when chakai were passed over, this appears to have been done without any reason given for the omission.

___________

*Some months in the Lunar Calendar have 30 days, and some have 29 days.

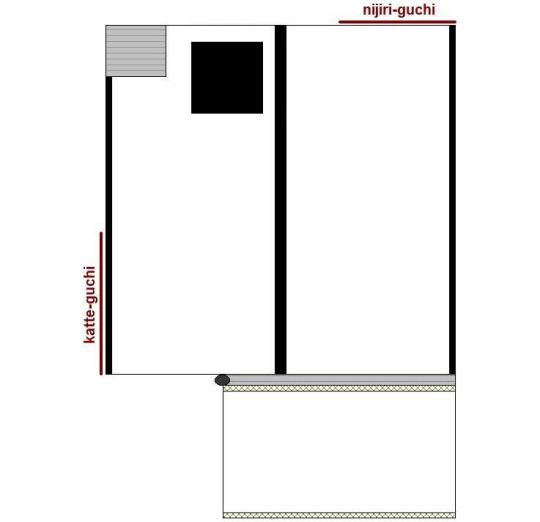

²Nijō shiki [二疊敷].

This was the 2-mat room in Rikyū's residence, which featured a tsuri-dana*.

The katte-guchi [勝手口]† opened onto the lower left side of the mat; and the room featured a geza-toko [下座床]‡ -- a toko that is located on the guests' left side, at the foot of the room -- all as shown in the above sketch.

__________

*This is an important point, because it immediately means that the furo had to be placed on the right side of the utensil mat -- since the furo cannot be located under the tsuri-dana.

†In modern-day chanoyu, this entrance is usually referred to as the sadō-guchi [茶道口].

‡The word can also be pronounced shita-za toko [下座床].

³Bungo Yoshimune [豊後義統].

This was Ōtomo Yoshimune [大友義統; 1558 ~ 1610]*, a daimyō-nobleman, Lord of Bungo, who was the eldest son and heir of Ōtomo Sōrin [大友宗麟]. He served as Captain of the Left Guards (sahyōe-no-kami [左兵衛督]), holding the junior grade of the Fifth Rank; and as an Imperial Chamberlain (jijū [侍従]) and Councillor of State (sangi [參議]), for which he received the junior grade of the Fourth Rank.

He also participated in the invasion of the continent; but apparently he exhibited cowardess when his forces encountered the Chinese and Korean armies, and for this Hideyoshi demanded that he forfeit the province of Bungo upon his return to Japan.

Nevertheless, Yoshimune sided with Ishida Mitsunari and the Western Army against Tokugawa Ieyasu at Sekigahara, for which he was exiled to Shishido in Hitachi, where he died in 1610.

Yoshimune had been baptized a Christian on the orders of his father†, but he seems to have been indifferent to the faith (unlike Ōtomo Sōrin himself). Some allege that he returned to the faith during his years in exile, but this is not substantiated by most of the documents that survive from that period.

__________

*In his other records, Rikyū usually writes this man's name either as Yoshimune [よしむね], written in kana; while his contemporaries generally wrote the name (in kanji) as Yoshimune [義宗]. That the correct form is found in this entry suggests that Jitsuzan probably corrected the material.

†His mother, though Sōrin's wife, was vehemently anti-Christian, and it seems that it was from her that Yoshimune inherited his religious apathy. His mother's name has been lost, and she is known to history only by the Jesuits' derogatory epithet of Jezebel.

⁴Tawara Yotsuo [田原四郎].

This refers to Ōtomo Chikamori [大友親盛; 1567 ~ 1643]*, third son of Ōtomo Sōrin, and a younger brother of Ōtomo Yoshimune. He remained a retainer of the daimyō of Bungo until Yoshimune was deposed in the aftermath of Hideyoshi’s first invasion of Korea. After that Chikamori gave his allegiance to Hosokawa Tadaoki (Hosokawa Sansai).

According to the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki [利休百會記], Chikamori also participated in a chakai that Rikyū gave for Ōtomo Yoshimune on the 22nd day of the Ninth Month of Tenshō 18 (1590).

__________

*Tawara was his mother's family, into which he was adopted in 1580.

⁵Rōju [良壽].

This refers to Akane-ya Rōju [茜屋良壽; the dates of his birth and death are unknown], a townsman of Sakai. His name is also given as Akane-ya Dōju [茜屋道壽] (which would seem to make him a fellow disciple of Araki [Kitamuki] Dōchin [荒木(北向き)道陳; 1504 ~ 1562] together with the young Rikyū: perhaps he and Rikyū were of a similar age). His name is occasionally mentioned in other documents associated with Rikyū, including the Hyakkai Ki.

⁶Sho [初].

The shoza.

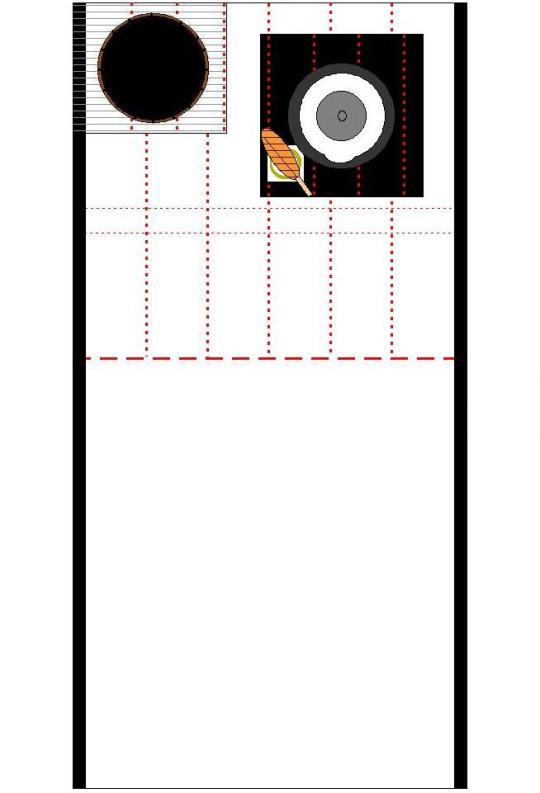

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the toko contained the scroll, and so was han [半];

- the furo, habōki, and kan were arranged on an ō-ita [大板]: and since the furo does not overlap the kane with which the other things were associated*, the room is assessed as being chō [調]†;

- and the sumi-tori, resting on the tana, made the tana han [半].

Han + chō + han is chō, which is appropriate for a chakai that is given during the daytime.

__________

*According to Book Three of the Nampō Roku, the kan and habōki should be placed on the left corner of the ō-ita, with a shiki-kami [敷き紙] (a piece of kaishi folded into a square 1- or 1-sun 2-bu larger than the diameter of the kan) placed down on the ō-ita underneath the kan; the feathers of the habōki then rest on top of the kan (as shown in the sketch). While ostensibly this was to protect the ita from being scratched, in fact it seems intended to insure that the kan-habōki arrangement touches the appropriate kane (just as when a shiki-kami was placed underneath the shin-nakatsugi).

It is important that the handle of the go-sun-hane not contact the kane that is associated with the furo (since, in that case, the kan and habōki would be counted together with the furo, throwing off the kane-wari count).

†The furo used on an ō-ita must always be a small furo (whether a bronze kimen-buro or one made of lacquered or glazed pottery), generally measuring between 8- and 9-sun in diameter. The little furo known as “bin-kake” [瓶掛] today (on which a tetsu-bin [鐵瓶] is heated) are representative of the size of this kind of furo.

Note that the arranging of a small furo on this large board is not an example of “contrast” (a small object placed on a large base) as some chajin held since the Edo period. Rather, the dimensions of the ō-ita were derived from those of the ji-ita of the small daisu, and the small kimen-buro was the furo that was made to be used on this kind of daisu.

⁷Tōyo [東與].

This refers to the bokuseki written by the Yuan period monk Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú [東陵永璵; 1285 ~ 1365]* (whose name was pronounced Tōryō Eiyo in Japanese). Rikyū used the first and last kanji of this monk’s name as his nickname for this scroll.

Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú was a follower of the Sōtō sect [曹洞宗]†, and came to Japan in Shōhei 6 [正平六年] (1351) to spread the teachings of this version of Chán among the Japanese.

___________

*When writing this abbreviated version of his name, Rikyū seems to have mistaken the second kanji -- writing yo [與] (the kanji that formed the first syllable of his own childhood name, Yoshirō [與四郎]), rather than yo [璵].

†One of the two main branches or schools of Zen. The other, of course, is the Rinzai School.

Though it is an over-simplification, the Sōtō approach tends to favor a more gradual attainment of realization through the cultivation of ones samadhi -- in contrast to the desire for a “sudden enlightenment” experience that is the goal of the followers of the Rinzai tradition.

⁸Ō-ita ni [大板ニ].

The ō-ita [大板], which measures 1-shaku 3-sun square*, was one of two shiki-ita† created by Jōō -- originally, so that the sumi-temae could be performed apart from the daisu‡, in order to reduce the wear-and-tear on the daisu as much as possible.

Because the ō-ita (and shi-hō-ita) was significantly larger than the furo**, the extra space was, from the start, used as a sort of tana -- that is, some of the things that would be needed for the sumi-temae (like the habōki, kan, kōgō, hibashi††) were displayed on the board (since the daisu, or naga-ita was set up elsewhere in the room). After the daisu was retired from general use, the hishaku and futaoki also came to be arranged on the ita, too.

By Rikyū's day, years after chanoyu had evolved away from the de rigeur use of the daisu, the employment of these various shiki-ita as a base for the furo throughout the entire gathering was already a long-established convention, and this is the practice that Rikyū follows in this chakai. Nothing out of the ordinary was being attempted by him here.

Traditionally the various shiki-ita were made from the ten-ita of old daisu (whose ji-ita was so damaged that they could no longer be used), because this wood is very old (and so stable -- it will not warp the way fresher wood will), and so are finished with shin-nuri [眞塗]. Because the ten-ita of the daisu was always 6-bu thick, this accounts for the thickness of the naga-ita and the various sizes of shiki-ita.

◎ When serving tea, the chakin, chashaku, and the lid of the chaire should be placed on the ō-ita: in particular, it is important to understand that the chashaku should not be rested on the chaire when an ō-ita is present in the room (the same is also true of the naga-ita: and this convention dates from the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who may have established the precedent).

__________

*The 1-shaku 4-sun ō-ita was created in the modern period, and it or its use have nothing to do with the classical object.

Jōō’s ō-ita also has nothing to do with the so-called naka-oki [中置き] style of arranging the utensil mat (where the furo is placed in the center of the mat).

†The ō-ita, which measures 1-shaku 3-sun square, was made for use with the small (bronze) kimen-buro that was used on the small daisu -- originally in a room covered with inakama tatami (which measure 5-shaku 9-sun by 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu).

The medium-sized kimen-buro was placed on a shi-hō-ita [四方板], which measured 1-shaku 2-sun from side to side, by 1-shaku. The medium furo was used on the large daisu, which could only be used in a room covered with kyōma tatami (measuring 6-shaku 3-sun by 3-shaku 1-sun 5-bu).

The large (usually iron) kimen-buro, which was used on the naga-ita (originally it was made for use on the o-chanoyu-dana, in the preparation room), was placed on a ko-ita [小板] measuring 9-sun 5-bu square -- again, originally only during the shoza (to protect the naga-ita from damage).

‡At the time when the ō-ita was made by Jōō, the daisu was used all of the time, hence the danger of scratching the lacquer by charcoal dust was a real issue.

During the Shino family’s kō-kai [香會] (and, of course, before), the charcoal was set alight and the kama was boiled in the preparation room or mizuya, and these things were brought out onto the utensil mat during the naka-dachi (which is why the guests had to leave the room and sit somewhere else while the furnishings were being changed). Jōō imitated the Shino’s way of handling things by placing the daisu (and kaigu, as well as the dai-temmoku and chaire) in the tokonoma during the shoza, while arranging the furo on a shiki-ita.

**The ō-ita is at least 2-sun larger than the furo on all four sides, and frequently it is even larger.

††Only bronze or sawari [四分一] hibashi could be arranged on the ō-ita -- the kind of hibashi that can be placed in the shaku-tate on the daisu or naga-ita. Iron hibashi were not supposed to be displayed in either of these ways.

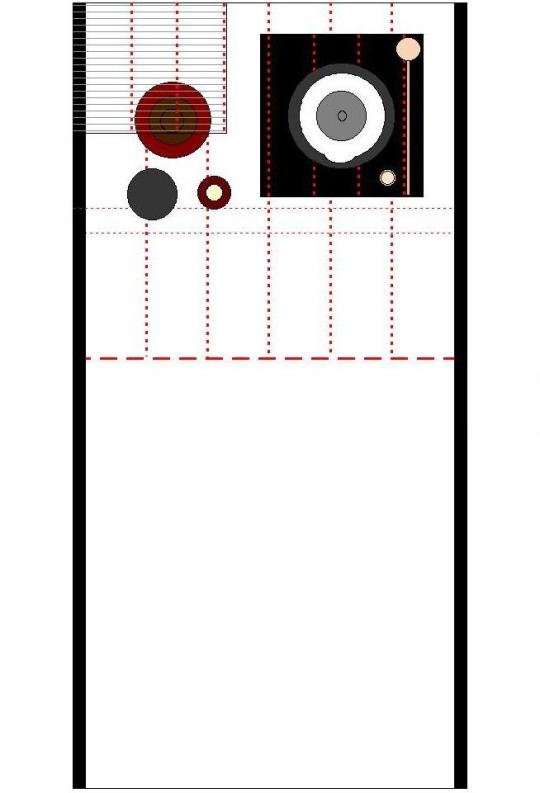

⁹Yuen-buro [油煙風爐].

Yuen [油煙] means soot, specifically that which comes from burning oil (hence, oily soot). Here, the expression yuen-buro means a do-buro [土風爐] (clay furo). Other early names for this type of furo were Nara-buro [奈良風爐]* and abura-buro [油風爐]† -- the latter being of a similar derivation to Rikyū's term.

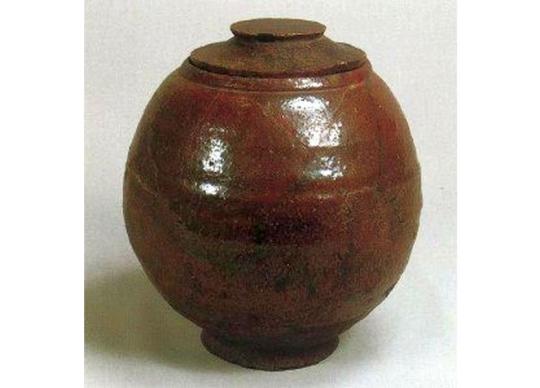

The specific furo in question is the one known today as the unryū-buro -- because it was made to be used with Rikyū's small unryū-gama‡. This furo is shown above.

The way to arrange the ō-ita and the furo on the utensil mat, together with the associated rules of kane-wari, will be discussed in a brief appendix that will follow this post.

__________

*Because they were originally made by the potters who produced low-fired earthenware vessels for one-time ritual use at the Kasuka Shrine [春日社] and Shōfuku-ji [興福寺] in Nara. Because of the single intended use, the earthenware was fired so low that, after soaking the piece in water for any length of time, it will fall apart (thus solving the problem of getting rid of hundreds or thousands of these pieces every day during the seasonal festivals).

†Since the original intention was to waterproof the clay, rather than color it, lacquer was applied with a cloth, which was used to rub the lacquer into the low-fired clay. Depending on the kind and quality of lacquer used, the result often looked as if the clay piece had simply been coated with oil -- or (to analyze Rikyū's term), rubbed with oily lamp-black.

By Rikyū's day, these furo were being fired at a higher temperature, and properly lacquered -- often (according to contemporary reports) with kagami-nuri [鏡塗], the highly polished black lacquer that is as reflective as a mirror.

‡The incurving rim and root-like legs of this furo recall the rounded shoulder and legs of the original old Temmyō kimen-buro for which Rikyū had designed the kama.

¹⁰Kama unryū [釜雲龍].

This was the second small unryū-gama, with matsukasa kan-tsuki and an iron lid that Rikyū had asked Yoshirō to make after he presented the original kama (along with the old Temmyō kimen-buro) to Hideyoshi, for use in his Yamazato-maru tearoom on the moat within the Ōsaka castle complex.

This kama is shown above, while the kama arranged on the yuen-buro is shown below.

¹¹Kan [クハン].

These were probably the same bronze kan that Rikyū used when hanging this kama over the ro.

The kan were placed on top of a shiki-kami [敷き紙], a piece of kaishi folded into a square that was 5- or 6-bu larger than the kan on all four sides. After arranging the kan on top of the shiki-kami, the habōki was rested on top of them.

¹²Habōki [羽帚].

This go-sun-hane [五寸羽] would have been made from right-feathers -- that is, feathers that are widest on the right side of the rachis.

The kind of feathers from which this go-sun-hane was made are unknown, since, in Rikyū's period, habōki were commonly used only once, so there was no real need to record such details. All that can be said with certainty is that, in the small room, a habōki with feathers 5-sun long was the rule.

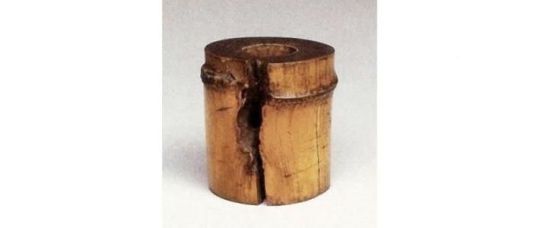

¹³Tana ni, na-kago ni sumi [棚ニ、菜籠ニ スミ].

This was Rikyū's abura-dake na-kago [油竹菜籠], shown below.

The kōgō (possibly Rikyū’s ruri-suzume kōgō [瑠璃雀香合], since this was his “ordinary kōgō”) was brought out from the katte at the beginning of the sumi-temae.

¹⁴Shiru hoshi-na sakura-gai [汁 干菜 ・ 櫻貝].

Hoshi-na [干菜] refers to the dried leaves (usually with the crown of the root still attached -- they are hung upside-down to dry, draped over a line) of the daikon. Since the crown of the root was usually chopped off in the market, the poor people would collect the discarded tops after the market closed, dry them, and then use them as a vegetable during the winter months when fresh vegetables were expensive. At this chakai, hoshi-na was used as a sort of delicacy, since they would prove to be a novel taste for the high-class guests at this chakai.

The sakura-gai is a kind of tellin -- a sand-burrowing clam (Nitidotellina nitidula), whose paired shells exhibit a clean, pink-colored nacre (the coating on the inner side of the shell) that is similar to the color of cherry blossoms (hence the Japanese name). The muscle would have been cut into small pieces and cooked by boiling in broth.

The soup was probably miso-shiru.

¹⁵Namasu [ナマス].

This is a sort of raw salad made from julienned daikon and carrot, dressed with rice vinegar that has been flavored (and diluted) with sake, mirin, and a little soy sauce.

¹⁶Kamaboko ・ unagi [カマホコ ・ ウナキ].

Kamaboko [蒲鉾] is a sort of steamed fish-paste made from white-fleshed fish. It was likely formed into small patties or tubes. Before serving, the kamaboko was deep fried in oil, in Rikyū's period.

Unagi [鰻] is the freshwater eel. It was probably lightly salted while it was roasting over a charcoal fire on skewers (this style of preparation is known as shira-yaki [白焼], and contrasts with the kaba-yaki [蒲焼] that is prepared by professional eel restaurants).

¹⁷Ae-mono [アヘモノ].

Ae-mono is another salad-like course that consists of various vegetables, and sometimes seafood, dressed with a soy- or iri-zake-based sauce.

¹⁸Senbei ・ iri-kaya ・ shiitake [センヘイ ・ イリカヤ ・ 椎茸].

These were the kashi [菓子]:

- senbei [煎餅] are rice crackers. Originally little more than the scorched rice from the bottom of a rice-pot, they were usually procured from a shop that specialized in senbei by Rikyū's day;

- iri-kaya [煎り榧] are the roasted nuts of the Japanese allspice tree (also known, in English, as the Japanese nutmeg-yew, Torreya nucifera);

- and the shiitake [椎茸], when prepared as kashi, would have been grilled over charcoal, and lightly salted.

¹⁹Go [後].

The goza.

As for the kane-wari:

- the tokonoma contained the chabana, suspended on the minor pillar on the wall-side of the toko, and so was chō [調];

- the room had the furo, together with the hishaku and futaoki, on the ō-ita; together with the mizusashi, with the chaire* and chawan arranged in front of it, as shown below, and so was han [半];

- and the tana was empty, and so chō [調].

Chō + han + chō is han, which is correct for the goza of a gathering held during the daytime.

__________

*This argument -- that the chaire was displayed without its tray -- is specifically made by both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō, and so reflects an interpretation that had been voiced in the earliest days of Nampō Roku scholarship.

Apparently, then, either Rikyū had decided to use the Nade-kata enza chaire without its tray on this occasion -- or, possibly, he decided to bring the tray out afterward, at the beginning of the koicha temae.

²⁰Toko makite [床巻テ].

That is, the kakemono was rolled up and taken away. “Toko makite” was Rikyū's shorthand way of stating this, for his records.

²¹Naga-fukube ni fuji-no-hana [長フクベニ 藤ノ花].

A naga-fukube [長瓢] is a fully-grown cucumber that has been dried and made into a kake-hanaire. One such, made by Rikyū, is shown below.

The hanaire was suspended from a hook that was attached to the minor pillar on the outer-wall-side of the tokonoma, near the bokuseki-mado (which, in Rikyū’s tearooms, was always located just outside of the toko).

²²Ō-ita, moto no mama ni hishaku ・ futaoki hikkiri [大板、元ノマヽニ ヒシヤク ・ 蓋置 引切].

The ō-ita and furo remained as they were during the shoza. However, when preparing for the goza, the hishaku and futaoki took the places previously occupied by the habōki and kan (and are counted in the kane-wari in the same way).

The futaoki would have been one of Rikyū's take-wa [竹輪], such as that shown above.

²³Mizusashi imo-gashira [水指 芋カシラ].

While Japanese scholars have long debated over the various possibilities for the place of origin of this mizusashi*, it is, in fact, a very typical example of early Joseon period ongi [온기 = 溫器] ware -- the typical brown-glazed pottery intended for day to day use, that was fired higher than unglazed earthenware (the purpose of the glaze was to make it waterproof). This jar was likely made to store agricultural seeds over the winter (the notch immediately below the mouth allowed a piece of cloth dipped in wax to be tied over the mouth, to keep the seeds fresh, so they could be planted in the spring).

The lid was not made for this vessel (and may well have been the product of a completely different pottery culture), and was likely added after the jar came to Japan.

___________

*This “imo-gashira” mizusashi should not be confused with Jōō’s imo-gashira mizusashi, shown below.

They are very different pieces, and the place of origin of Jōō’s mizusashi is questionable (though somewhere in the area of South-east Asia referred to as “Namban” [南蠻] does seem most likely). A large part of the “scholarly debate” appears to be the result of confusing one of these mizusashi with the other.

²⁴Chaire Enza [茶入 圓座].

This was the meibutsu Nade-kata enza chaire [撫肩圓座茶入] that had once belonged to Jōō.

Rikyū had received this chaire, from Hideyoshi, the year before -- probably so that Rikyū would have a “good” chaire to use when serving tea to Hideyoshi and his important guests (Ōtomo Yoshimune was just such a person)*.

While nothing is mentioned, it seems most likely that the chaire was placed on the square tray that Rikyū had made for it after receiving the chaire from Hideyoshi†; and he would have used an ori-tame [折撓] that he made to match as the chashaku. (The chashaku shown above, now known by the name of “Namida” [泪], which was given to it by Furuta Sōshitsu at the time of Rikyū’s seppuku, is one that Rikyū made to be used with this bon-chaire.)

__________

*Rikyū’s own treasured chaire that was paired with a tray -- which he referred to by the name of Shiri-bukura [尻フクラ = 尻膨] -- is asymmetrical. This imperfection lessened it in the eyes of his contemporaries (including Hideyoshi).

†The chaire had not been paired with a Chinese tray. However, due to its quality, Jōō felt that it was not appropriate to stand it directly on the mat, and so he had a tray made in the style of the Haneda-bon [羽田盆], albeit with a red edge (which was one of Jōō’s favorite touches, and would serve to indicate that this tray was not from an earlier period in the eyes of posterity).

Because Rikyū preferred to use trays that were only 2-sun larger than the chaire on all four sides (so that the chawan could be stood next to the bon-chaire just as if a tray were not present), he had a new tray made -- also in the Haneda-bon style (though without the red). This is the tray that is shown in the photo, and the one he probably used during this chakai.

²⁵Chawan kuro [茶碗 黒].

This would have been one of Furuta Sōshitsu's creations*, probably the one that Rikyū has mentioned using on several earlier occasions in this kaiki.

The chawan shown above, which bears Rikyū's kaō, and so may be the bowl that was used during this gathering.

And, though not mentioned, the koboshi was most likely a mentsū [面桶] -- which (in addition to its being the appropriate koboshi for use in the small room setting) would account for Rikyū's failure to note it down in his kaiki.

___________

*The black bowls made for Rikyū by Chōjirō did not begin to appear until the late summer or autumn of the present year (1587); thus, any reference to a “kuro-chawan” [黒茶碗] prior to that time must refer to one of the bowls made by Furuta Sōshitsu at the Seto kilns. Oribe, of course, seems to have been the inventor of the hiki-dashi [引き出し] technique. (The potters do something of the sort as a way to test the degree of firing, but they always discard the pieces so sacrificed. Oribe’s achievement was in recognizing the possibilities that plucking a piece of pottery out of the kiln while it was still red-hot, and then rapidly cooling it, made for enhancing the texture of the Seto black glaze. It was this technique that Chōjirō subsequently imitated in the creation of his own black bowls.)

1 note

·

View note