#illustrated-ghibli-esque-variations

Photo

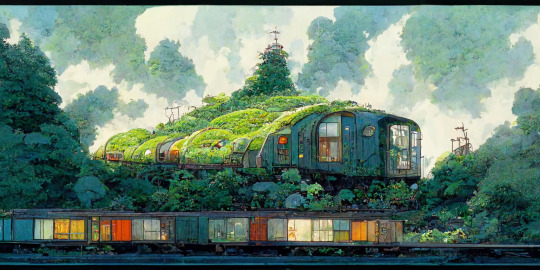

Post Tomorrow Hyper Stained Glass Train Abodes

further variations on these in a more stylized view

by ghost owl attic

#ai#midjourney#stainedglasstrains#stained glass trains#stained glass#abodes#natural living#dream house#ghibli#moretrains#more of an illustrated variation#illustrated-ghibli-esque-variations#green homes#alternative homes#living#reuserevolution#reuse#reusable#tomorrow#futuristic#solar punk#nature#trains#train#traincar#car#trees

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Is it possible to go home again? Are your favorite books of childhood actually as good as you remember? Or should they simply remain just that, memories, never to be revisited? I went back to my childhood touchstones to see. The results were varied and interesting.

Chronicles of Narnia

by CS Lewis

One of the earliest of my childhood loves to be taken off a pedestal. I was near obsessed with these novels as a child. I found the amount of world-building to be enthralling. It felt grounded and fantastic, and there always seemed to be more out there to be discovered. However, my memory failed me a bit regarding the specifics of the later books (or earlier depending on your preferred reading order).

Revisiting this was crushing. I suddenly remembered being put off by the nonsensical rules that seemed to govern Narnia… sometimes. And Aslan never. There were holes in the storytelling that eclipsed the actual story. And the Christianity. It’s not fair to call it symbolism or imagery. The reason I kept petering out toward the end of the series is that it goes from Christian allegory to a blatant Christian bible retelling. Which, both as a child and adult, is incredibly unfulfilling. But to my younger self, the Rapture ending was unforgivable. There was enough magic in Narnia and the other realms to save everything. Either the people could have rallied, or the citizens of Narnia, or Aslan. In order to stick with the canonical bible ending, Lewis was forced to write an ending where everyone essentially either forgets their power or forgoes their power, giving up and running away. It’s dull, derivative, and didn’t really hold up when I was a kid.

Still, there are aspects of the world-building that appealed to me as an adult. The parts that aren’t Christian, that is. There’s a mundanity to the magic that seems both sincere and slightly ironic. That sensibility is what I’ve kept with me. The fact that after magic is discovered then it simply is. The act of discovery can’t go on forever, and at some point the magic will either be gone or become part of every-day life. And the latter is what Narnia showed me.

Jeremy Thatcher, Dragon Hatcher

by Bruce Coville

I was the most nervous about picking this one back up. I’ve written at length about this book meant and means to me. My adult self is delighted to tell you that this book still works. Not necessarily on a prose level. The story is very simple, many details that I recall likely came from my imagination. It moved along as was over before I expected. It was, dare I say, breezy. The book was a perfect cocktail for my younger self because it was made of two ingredients.

The first was Jeremy Thatcher and his dragon. He was simplistic enough that my imagination could put me in his shoes, and his emotional bond with the dragon Tiamat. Style aside, the fact that I had a book with an emotional core to latch on to, rather than the story-driven books I was used to (a la Louis Sachar and the like). That just clicked with me. It stood out from the rest of my books at the time. This variation was showing me a difference between drama and emotional resonance. Did I understand that at the time? Hell no. But I had a book I could get emotional over that featured a dragon.

The other is the framing device of S.H. Elives’ Magic Shop. The shop shows up across a number of titles by Bruce Coville, creating a loose series. The fact that it was a place that revealed itself to each protagonist gave me just a bit of day-dream fuel that the next time I was walking home from school on a foggy day or just biking around town I had a small chance of finding an old shopfront I had never noticed before. And whereas with the wardrobe you get Narnia, or with an owl letter you get Hogwarts, the shop was so mysteriously stocked that I would often wonder what item should call to me from the shelves.

So yeah, this book still has some magic in it. It didn’t blow me away now, but I can clearly see all the parts that cemented it into my imagination as a child.

A Wrinkle in Time

by Madeleine L’Engle

This one is probably the most disappointing revisit. I absolutely adored these books as a child. And unlike the Narnia books, I whole-heatedly loved the entire quintet. But upon revisiting these they were the biggest fall from grace, so to speak. Unlike the Narnia books they aren’t blatantly Christian, but they are blatantly pro-religion. There’s a pervasive, albeit holistic, focus on selfless devotion, grace, and faith. To some that may not sound terrible, but I remembered these as being about children who found personal strength. The focus on faith takes away some of their agency and replaces it with a weak version of destiny.

Faith in and of itself is not a good thing. It is made through the pairing of belief and an absence of evidence, which is a terrible combination. Faith, both in definition and in practice within these books, requires a certain degree of ignorance. Faith without ignorance becomes confidence and loyalty. These books made me appreciate mysteries as a part of life, but I hadn’t realized how much they also eschewed the act of solving said mysteries.The takeaway I had with this series as that as a child I believed they were about strength and perseverance, but as an adult they have a strange reliance on faith and fatalism.

Tom Swift Jr. (Tom Swift IV)

Jesus, what was I thinking? The takeaway from these? Shame. Actually, that was what they taught me back then, as well. I stopped reading them after I had chosen it for a “what did you read over the summer” book report in elementary school and then was too embarrassed to talk about it for my presentation. I got a zero.

Okay, in all honesty I could see an anthology TV show being made of these today. They would be over-the-top faux 90s nostalgia and based solely on the covers, rather than any of the actual novels. They’d be produced by (and first episode directed by) Chris Miller & Phil Lord or John Carpenter, depending on how much they wanted to lean into the humor. And lord help me, I’d probably watch it.

The House with a Clock in its Walls

by John Bellairs

This was an odd one. If you’ve ever revisited grade school as an adult you know how everything seems so much smaller. Well, the prose felt smaller. I remembered these books as dripping with a wry darkness. Not sinister, but macabre and mysterious. They don’t read that way to me now. Granted, they’re not bundles of sunshine. There’s death, children in peril, and well-meaning adults keeping kids in danger because they don’t believe they need all the facts. This isn’t the dark favorite I remember.

But it’s the foundation of it. There are elements that, when properly fermented and aged, will grow into my love of dark literature and sinister storytelling. There’s danger without cruelty. There’s darkness and the threat of violence, but it’s the mystery that fuels it all, not the threat of death. Death is just the seasoning, and that’s still pretty satisfying.

And then there are the illustrations. These books, or at least the editions I read and re-read, are illustrated by the illustrious Edward Gorey. Whether or not you know the name, there is little doubt you know his art. His creepy Victorian/Edwardian-esque art probably has at least as much to do with what I took away from these books as the text. I don’t really feel the need to contextualize that aspect of these books. It’s Edward Gorey. I loved his art then and I love it now.

Hexwood

by Diana Wynne Jones

This one is probably the strangest and most complicated as far as lasting influence and how well it holds up over time. This book may be the only one that could be considered more solid now than when I read it as a child.

The plot is bizarre and convoluted and purposefully opaque. The book is dense. I had a bit of a touch go with it this time around, though don’t remember it being a particularly hard read as a child. Now it comes across as a mix between Jeff Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation and the Canadian horror film Cube. But for kids.

Looking outside just the plot, the author, Diana Wynne Jones, dedicated this novel to Neil Gaiman, who had previously dedicated his mini-series The Books of Magic to four witches, one of which was her. There’s also the fact that the Studio Ghibli film Howl’s Moving Castle is based on one of her novels, something I did not know when I first saw it. Coming back to this book, with all these pop-culture threads that have woven back into my life, was like finding out that someone you befriended recently was in the background of some of your childhood vacation photos. It’s strange and unsettling but also a little comforting in a cosmic way. Like a little validation from the universe about who I am and what I like today.

There are countless books I did not go back to, including The Tripods trilogy by John Christopher, The Time Warp Trio by Jon Scieszka and Catwings by Ursula K. Le Guin. These weren’t out of fear so much as I realized that once I finished the titles that came immediately to mind there really wasn’t a point on delving deeper. These books all made my childhood to one extent or another. Some were emotionally fulfilling, others helped build my literary taste and personal aesthetics. The point isn’t whether they’re still fulfilling to me now, but that they served their purpose at the time. A Wrinkle in Time’s awkward religion felt like a huge blow to discover, but it’s not that bad. I tore through those books as a kid, often identifying with Meg and sometimes oddly put off by Charles Wallace. But that series left a desire for mystery in my genre stories. I liked that there was always more somewhere else in their world. The Narnia chronicles gave me a taste for concrete world-building, for an underlying mechanic and logic in the substructure of a book. This eventually led me to delight in the construction of Eric Nylund’s fantasy and is probably why the Feed and Wayward Children books by Seanan McGuire are utterly compelling and fulfilling to me as an adult. The John Bellairs books gave me a taste of the macabre with prose, and a second helping of darkness from the Edward Gorey illustrations.

That might seem like an obvious lesson, but it’s still worth learning on your own. There’s a security in knowing that while a loved story from youth may lose its appeal, that doesn’t make it any less meaningful. None of my subsequent loves and discoveries came tumbling down. I think there’s a strength in knowing that first-hand. It lets me be less precious with what I loved in the past. And when some of those old stories turn out to hold up, it makes them all the more magnificent.

Nostalgia calls! But do these classics from my childhood hold up? Can You Go Home Again? Revisiting Favorite Childhood Books Is it possible to go home again? Are your favorite books of childhood actually as good as you remember?

#A Wrinkle in Time#Bruce Coville#Catwings#Chronicles of Narnia#CS Lewis#Diana Wynne Jones#Hexwood#Jeremy Thatcher Dragon Hatcher#John Bellairs#John Christopher#Jon Scieszka#Madeleine L&039;Engle#The House with a Clock in its Walls#The Time Warp Trio#The Tripods#Tom Swift Junior#Ursula K. Le Guin

0 notes