#hornsea

Photo

A girl from Wakefield Seaside School practicing cartwheels on the beach at Hornsea

Haywood Magee, “Wakefield Goes to Sea,” Picture Post, Aug 7, 1948

#1940s#1940s fashion#vintage fashion#england#vintage#haywood magee#cartwheels#picture post#wakefield seaside school#hornsea seaside school#wakefield#hornsea#yorkshire#uk#united kingdom#black and white#photography#photo restoration

77 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

The Hull To Hornsea (1996) - Kevin Walton

A stop-motion journey along the abandoned Hull to Hornsea railway.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Train beaker

Mug

1969 (designed), William John Clappison

from the V&A collection;

We'd call it a mug now, but back in the day it was still a beaker.

0 notes

Text

February Coming…

Storm up storm up

Wind flying flailing mad

Angry at the sky ground sea

Waves crashing o’er me

Rattling bones of stones

The ocean’s carcass

Dragging on the coast again

A car floats

Slowly down

South Promenade

While we huddle

Against the rage.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

GrahamArt represented at the Gallery, Hornsea

I am very happy to have been invited to become a part of The Gallery in Hornsea where visitors can view the work of some of the many gifted artists in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Interior of the Gallery, Hornsea

A range of work is on view from lively abstract paintings to landscapes, seascapes and nature. Many works feature the form, buildings, boats and creatures of the sea.

The Gallery,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Excited to share the latest addition to my #etsy shop: Pair of #1960s #Vintage #Hornsea egg cups #breakfast #eggholders #vintageeggcups #eggs #tableware https://etsy.me/3Nkacj6 (at Bognor Regis) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cdoi4yltbLD/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

The 1.32 GW Hornsea Two will dethrone the 1.2 GW Hornsea One as the largest operating offshore wind farms in the world. It’s 462 square kilometers (178 square miles) in size, and it will power more than 1.3 million homes.

Hornsea Two is off the east coast of England and was developed and is owned by Danish wind giant Ørsted. It features 165 Siemens Gamesa 8 megawatt (MW) turbines; most of the wind turbines’ blades were manufactured at Siemens Gamesa’s factory in Hull.

All of Hornsea Two’s wind turbines are now commercially operational. The entire project will be fully commissioned after the final reliability runs are completed, and that’s expected later this month.

#UK#Hornsea Two#wind power#offshore wind#renewable energy#fossil fuel phase-out#energy safety#energy independence#cheap electricity#Europe#very good news

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

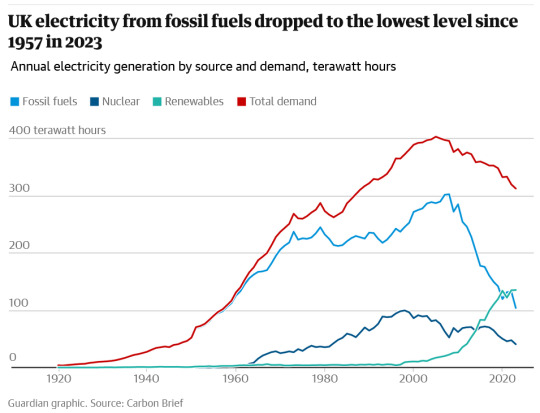

"The amount of electricity generated by the UK’s gas and coal power plants fell by 20% last year, with consumption of fossil fuels at its lowest level since 1957.

Not since Harold Macmillan was the UK prime minister and the Beatles’ John Lennon and Paul McCartney met for the first time has the UK used less coal and gas.

The UK’s gas power plants last year generated 31% of the UK’s electricity, or 98 terawatt hours (TWh), according to a report by the industry journal Carbon Brief, while the UK’s last remaining coal plant produced enough electricity to meet just 1% of the UK’s power demand or 4TWh.

Fossil fuels were squeezed out of the electricity system by a surge in renewable energy generation combined with higher electricity imports from France and Norway and a long-term trend of falling demand.

Higher power imports last year were driven by an increase in nuclear power from France and hydropower from Norway in 2023. This marked a reversal from 2022 when a string of nuclear outages in France helped make the UK a net exporter of electricity for the first time.

Carbon Brief found that gas and coal power plants made up just over a third of the UK’s electricity supplies in 2023, while renewable energy provided the single largest source of power to the grid at a record 42%.

It was the third year this decade that renewable energy sources, including wind, solar, hydro and biomass power, outperformed fossil fuels [in the UK], according to the analysis. Renewables and Britain’s nuclear reactors, which generated 13% of electricity supplies last year, helped low-carbon electricity make up 55% of the UK’s electricity in 2023.

[Note: "Third year this decade" refers to the UK specifically, not global; there are several countries that already run on 100% renewable energy, and more above 90% renewable. Also, though, there have only been four years this decade so far! So three out of four is pretty good!]

Dan McGrail, the chief executive of RenewableUK, said the data shows “the central role that wind, solar and other clean power sources are consistently playing in Britain’s energy transition”.

“We’re working closely with the government to accelerate the pace at which we build new projects and new supply chains in the face of intense global competition, as everyone is trying to replicate our success,” McGrail said.

Electricity from fossil fuels was two-thirds lower in 2023 compared with its peak in 2008, according to Carbon Brief. It found that coal has dropped by 97% and gas by 43% in the last 15 years.

Coal power is expected to fall further in 2024 after the planned shutdown of Britain’s last remaining coal plant in September. The Ratcliffe on Soar coal plant, owned by the German utility Uniper, is scheduled to shut before next winter after generating power for over 55 years.

Renewable energy has increased sixfold since 2008 as the UK has constructed more wind and solar farms, and the large Drax coal plant has converted some of its generating units to burn biomass pellets.

Electricity demand has tumbled by 22% since its peak in 2005, according to the data, as part of a long-term trend driven by more energy efficient homes and appliances as well as a decline in the UK’s manufacturing sector.

Demand for electricity is expected to double as the UK aims to cut emissions to net zero by 2050 because the plan relies heavily on replacing fossil fuel transport and heating with electric alternatives.

In recent weeks [aka at the end of 2023], offshore wind developers have given the green light to another four large windfarms in UK waters, including the world’s largest offshore windfarm at Hornsea 3, which will be built off the North Yorkshire coast by Denmark’s Ørsted."

-via The Guardian, January 2, 2024

#uk#united kingdom#england#scotland#wales#northern ireland#electricity#renewables#renewable energy#climate change#sustainability#hope posting#green energy#fossil fuels#oil#coal#solar power#wind power#environment#climate action#global warming#air pollution#climate crisis#good news#hope

384 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A girl kneeling by her bed saying good night prayers in the dormitory of Wakefield holiday school at Hornsea

Haywood Magee, “Wakefield Goes to Sea,” Picture Post, Aug 7, 1948

#prayer#1940s#1940s fashion#england#vintage fashion#vintage#haywood magee#picture post#wakefield#hornsea#wakefield seaside school#hornsea seaside school#yorkshire#uk#black and white#photography#photo restoration#united kingdom

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tracklist:

Intro • Hello My Love; How is You? • Deans On a Train • Playing Poet To Pass The Time • Pierre Are You There? • Masochism Tango (Interlude) • Tokyo • Poppin' Candy Daydreams • Rosemary Court • Ezekiel (Interlude) • καλών (Kalowne) • Adolescent Existence • Hornsea • Batter My Head In (With A Fax Machine) • Parlance • Kismet Kissings • I've Been Dreaming • Skinny Bookish Debutante • Knee Bruises • Outro

Spotify ♪ Youtube

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Russia ramps up its second offensive, a debate has erupted over whether Moscow or Kyiv will have the upper hand in 2023. While important, such discourse also misses a larger point related to the conflict’s longer-term consequences. In the long run, the true loser of the war is already clear; Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will be remembered as a historic folly that left Russia economically, demographically, and geopolitically worse off.

Start with the lynchpin of Russia’s economy: energy. In contrast to Europe’s (very real) dependence on Russia for fossil fuels, Russia’s economic dependence on Europe has largely gone unremarked upon. As late as 2021, for example, Russia exported 32 percent of its coal, 49 percent of its oil, and a staggering 74 percent of its gas to OECD Europe alone. Add in Japan, South Korea, and non-OECD European countries that have joined Western sanctions against Russia, and the figure is even higher. A trickle of Russian energy continues to flow into Europe, but as the European Union makes good on its commitment to phase out Russian oil and gas, Moscow may soon find itself shut out of its most lucrative export market.

In a petrostate like Russia that derives 45 percent of its federal budget from fossil fuels, the impact of this market isolation is hard to overstate. Oil and coal exports are fungible, and Moscow has indeed been able to redirect them to countries such as India and China (albeit at discounted rates, higher costs, and lower profits). Gas, however, is much harder to reroute because of the infrastructure needed to transport it. With its $400 billion gas pipeline to China, Russia has managed some progress on this front, but it will take years to match current capacity to the EU. In any case, China’s leverage as a single buyer makes it a poor substitute for Europe, where Russia can bid countries against one another.

This market isolation, however, would be survivable were it not for the gravest unintended consequence of Russia’s war—an accelerated transition toward decarbonization. It took a gross violation of international law, but Putin managed to convince Western leaders to finally treat independence from fossil fuels as a national security issue and not just an environmental one.

This is best seen in Europe’s turbocharged transition toward renewable energy, where permitting processes that used to take years are being pushed up. A few months after the invasion, for example, Germany jump-started construction on what will soon be Europe’s largest solar plant. Around the same time, Britain accelerated progress on Hornsea 3, slated to become the world’s largest offshore wind farm upon completion. The results already speak for themselves; for the first time ever last year, wind and solar combined for a higher share of electrical generation in Europe than oil and gas. And this says nothing of other decarbonization efforts such as subsidies for heat pumps in the EU, incentives for clean energy in the United States, and higher electric vehicle uptake everywhere.

The cumulative effect for Russia could not be worse. Sooner or later, lower demand for fossil fuels will dramatically and permanently lower the price for oil and gas—an existential threat to Russia’s economy. When increased U.S. shale production depressed oil prices in 2014, for example, Russia experienced a financial crisis. Lower global demand for fossil fuels will play out over a longer timeline, but the result for Russia will be much graver. With its invasion, Russia hastened the arrival of an energy transition that promises to unravel its economy.

Beyond a smaller and less efficient economy, Putin’s war in Ukraine will also leave Russia with a smaller and less dynamic population. Russia’s demographic problems are well-documented, and Putin had intended to start reversing the country’s long-running population decline in 2022. In a morbid twist, the year is likelier to mark the start of its irrevocable fall. The confluence of COVID and an inverted demographic pyramid already made Russia’s demographic outlook dire. The addition of war has made it catastrophic.

To understand why, it’s important to understand the demographic scar left by the 1990s. In the chaos that followed the Soviet Union’s dissolution, Russia’s birthrate plunged to 1.2 children per woman, far below the 2.1 needed for a population to remain stable. The effects can still be seen today; while there are 12 million Russians aged 30-34 (born just before the breakup of the Soviet Union), there are just 7 million aged 20-24 (born during the chaos that followed it). That deficit meant Russia’s population was already poised to fall, simply because a smaller number of people would be able to have children in the first place.

Russia’s invasion has made this bad demographic hand cataclysmic. At least 120,000 Russian soldiers have died so far—many in their 20s and from the same small generation Russia can scarcely afford to lose. Many more have emigrated, if they can, or simply fled to other countries to try to wait out the war; exact numbers are hard to calculate, but the 32,000 Russians who have immigrated to Israel alone suggest the total number approaches a million.

Disastrously, the planning horizons of Russian families have been upended; it is projected that fewer than 1.2 million Russian babies may be born next year, , which would leave Russia with its lowest birthrate since 2000. A spike in violent crime, a rise in alcohol consumption, and other factors that collude against a family’s decision to have children may depress the birthrate further still. Ironically, over the last decade Putin managed to slow (if not reverse) Russia’s population decline through lavish payoffs for new mothers. Increased military spending and the debt needed to finance it will make such generous natalist policies harder.

The invasion has left Russia even worse off geopolitically. Unlike hard numbers and demographic data, such lost influence is hard to measure. But it can be seen everywhere, from public opinion polls across the West to United Nations votes that the Kremlin has lost by margins as high as 141 to 5. It can also be seen in Russia’s own backyard; while an emboldened NATO could soon include Sweden and Finland, Russia’s own Collective Security Treaty Organization is tearing at the seams as traditional allies such as Kazakhstan and Armenia realize the Kremlin’s impotence and look to China for security.

Perhaps most important of all, Russia has reinvigorated the cause of liberal democracy. In the year after its invasion, French President Emmanuel Macron won a rare second term in France, the far-right AfD lost ground in three successive elections in Germany, and “Make America Great Again” Republicans paid an electoral penalty in the U.S. midterms. (The far right did sweep into power in both Sweden and Italy, but such wins have so far failed to dent Western unity and appear more motivated by immigration.) And this says nothing of the wave of democratic consolidation playing out across Eastern Europe, where voters have thrown out illiberal populists in Slovenia and Czechia in the last year alone. It is impossible to attribute any of these outcomes to just one factor (U.S. Democrats also got a boost from the overturn of Roe v. Wade and election denialism, for example), but Russia’s invasion—and the clear choice between liberalism and autocracy it presented—no doubt helped.

Nowhere, however, has Russia’s invasion backfired more than in Ukraine. Contrary to Putin’s historical revisionism, Ukraine has long had a national identity distinct from Russia’s. But it’s also long been fractured along linguistic lines, with many of its elites intent on maintaining close relations with the Kremlin and even the public unsure about greater alignment with the West.

No longer. Ninety-one percent of Ukrainians now favor joining NATO, a figure unthinkable just a decade ago. Eighty-five percent of Ukrainians consider themselves Ukrainian above all else, a marker of civic identity that has grown by double digits since Russia’s invasion. Far from protecting the Russian language in Ukraine, Putin appears to have hastened its demise as native Russian speakers (Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky included) switch to Ukrainian en masse. Putin launched his invasion to bring Ukraine back into Moscow’s orbit. He has instead anchored its future in the West.

Of course, one can argue that, however much the war has cost Russia, it has cost Ukraine exponentially more. This is true. Ukraine’s economy shrank by more than 30 percent last year, while Russia’s economy contracted by just about 3 percent. And this says nothing of the human toll Ukraine has suffered. But, like Brexit, Western sanctions on Russia will play out as a slow burn, not an immediate collapse. And while Russia enters a protracted period of economic and demographic decline, once peace comes, Ukraine will have the combined industrial capacity of the EU, United States, and United Kingdom to support it as the West’s newest institutional member—precisely the outcome Putin hoped to avoid. Russia may yet make new territorial gains in the Donbas. But in the long run, such gains are immaterial—Russia has already lost.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

NaPoWriMo Day One: Hornsea Mist

[Image ID: A gloomy cloudy sky over choppy, greyish brown waves topped with white foam.] Hornsea beach.

The mist over the sea comes in hard

White fuzz, silencing the horizon

While the shoreline cracks and hammers

Wave after wave of angry

Turning tide.

The town gathers anyway

Braving the blustery spittle

High-vis high octane madness:

Carts and coats and concerts

Singing gutsy enough

To…

View On WordPress

#GloPoWriMo#hornsea#Hornsea Carnival#napowrimo#NaPoWriMo 2023#poem#poems#Poet#poetry#poets#yorkshire

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hornsea Art Society Annual Exhibition 2023

I have a painting in the notable local East Riding art exhibition, the Hornsea Art Society Annual Exhibition 2023. The painting is called ‘Meditating Woman’.

Woman meditating in the summer

This year’s exhibition is held in the Hornsea Bowling Club, where you will receive a friendly welcome from the staff, members and artists.

The exhibition features art of all kinds and is organised into…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

visit hornsea we have: liver. tree root. trapped ancient plant jamboree.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Excited to share the latest addition to my #etsy shop: 8cm Hornsea Vintage 1977 Queen Elizabeth silver jubilee mug #Hornsea #jubilee #silverjubilee #mothersday #platignumjubilee #royalmemorabilia #vintagecoronation https://etsy.me/3kbI9Wt (at Bognor Regis) https://www.instagram.com/p/CcwBSwoNUBu/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes