#ghost movies

Text

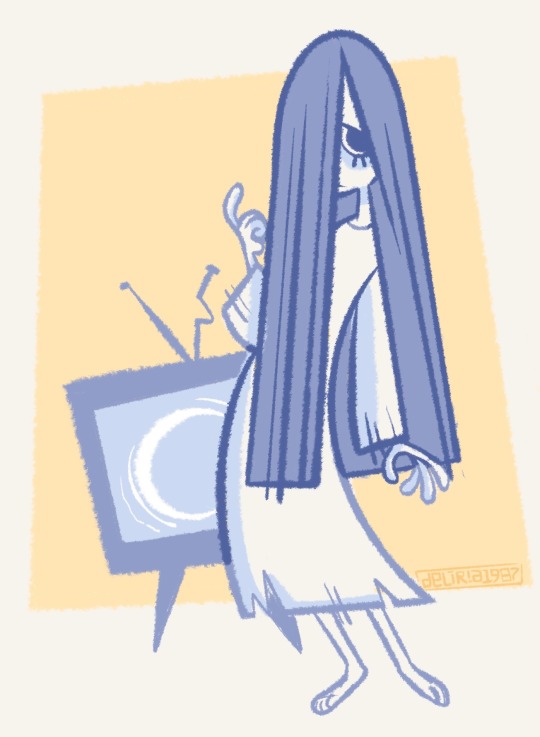

Sadako (ring-ing in the new year) 📼

#my art#sadako#sadako yamamura#the ring#ringu 1998#the ring 2002#samara morgan#j horror#ghosts#horror fanart#horror#ghost movies#horror art#horror movies#digital art#digital illustration#illustration#character design

533 notes

·

View notes

Text

Secrets in the Hot Spring is a modern Chinese Scooby Doo episode and everything that implies. A sweet story about family and friendship and shirtless guys. There’s a sight gag early on that made me laugh my full ass off.

#halloween hundred#halloween hundreds#halloween#horror movies#halloween movie#horror film#horror#ghost movies#foreign horror#Chinese horror#international horror#secrets in the hot spring#horror comedy

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 Ghosts (1960). Having some fun with some ye olde classic campy William Castle ghost movies.

#horror#movies#cinema#horror film#film#william castle#13 ghosts#classic horror#old horror#classic horror movies#classic movies#old movies#ghost movies#spirits#evil#black and white movies#classic cinema#cinematic#films#film aesthetic#horror films#spooky#spooky movies

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

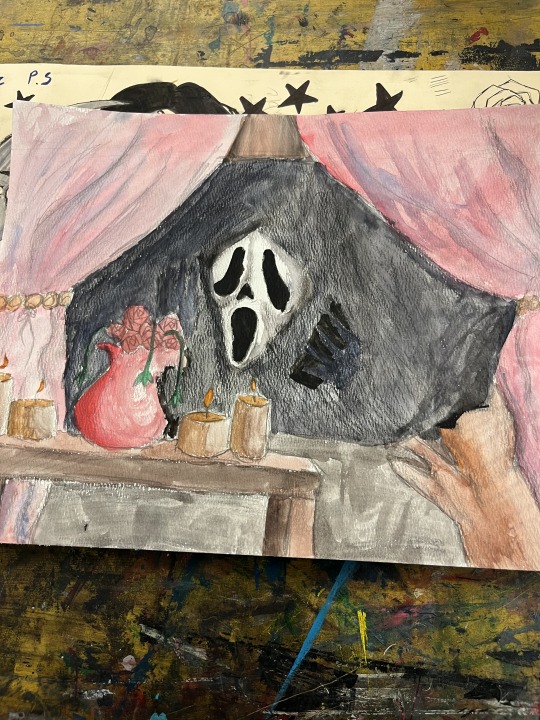

Cute?

#Ghost face#ghost movies#ghostface#ghost#horror#movies#scream movie#slashers#scream franchise#scream#scream movies#scream vi#scream 1996#Fanart#art#teen artist

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

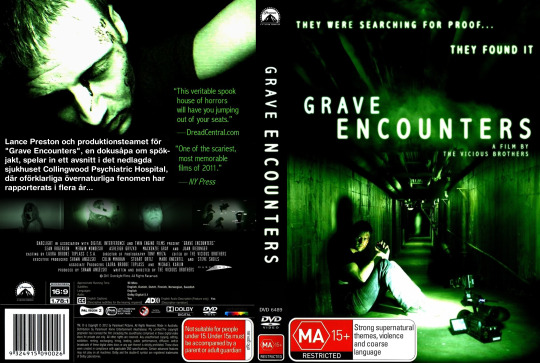

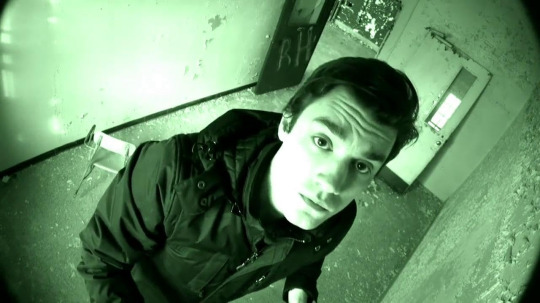

Grave Encounters (2011)

Widely regarded as one of the best paranormal found footage films, and one that actually does live up to the hype. The characters are believable—and tolerable—the location is proper creepy and most of the film maintains a very spooky atmosphere while also providing a healthy does of what would later come to be known as liminal horror.

However, like a lot of other films in this particular niche, they do at times push what they show to a level that can negatively impact the feeling of believability that the rest of the movie works to provide... especially with the cheaply-manipulated jump scare faces on the ghosts.

7/10

#hauntings#7/10#2010s#horror#horror movies#2010s horror#ghost movies#found footage#hospital#grave encounters

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

31 Days of Horror

Day 3 - Favorite Ghost Movie

Thirteen Ghosts (2001)

Starring:

Matthew Lillard

Tony Shalhoub

Shannon Elizabeth

Rah Digga

JR Bourne

Synopsis: Arthur and his two children, Kathy and Bobby, inherit his Uncle Cyrus's estate: a glass house that serves as a prison to 12 ghosts. When the family, accompanied by Bobby's Nanny and an attorney, enter the house they find themselves trapped inside an evil machine "designed by the devil and powered by the dead" to open the Eye of Hell. Aided by Dennis, a ghost hunter, and his rival Kalina, a ghost rights activist out to set the ghosts free, the group must do what they can to get out of the house alive.

13 Ghosts Kill Count: 12 according to Dead Meat.

Favorite Kill Scene: Matthew Lillard's character getting his back broken by The Juggernaut.

Favorite Ghost: The Jackal. A mental case murderer who died in an asylum. As soon as he’s let out he runs out of the gate attacking. And the entire movie all the ghosts are slow paced and just chill. Not Jackal. Nope. He wants to play. He’s going to play. Thirteen Ghosts is his movie.

What was your favorite ghost movie?

#31 days of horror#thirteen ghosts#podcaster#horror movies#podcastblr#ghost movies#podcast#from under the apron

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Ghost Story

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

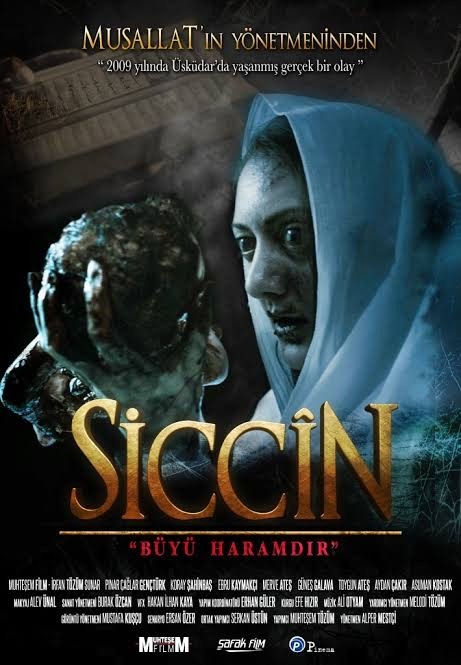

horror movies with really unexpected plot twists (in my opinion)

1. High Tension/Haute Tension(2003)

2. Incident In A Ghostland(2018)

3. Siccîn(2014)

#horror#horror movies#scary movies#horror genre#ghost movies#thriller#thriller movies#plot twist#movie recommendation#movies recommendations

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

High Spirits (1988)

When a hotelier attempts to fill the chronic vacancies at his castle by launching an advertising campaign that falsely portrays the property as haunted, two actual ghosts show up and end up falling for two guests.

#movie#jennifer tilly#peter o'toole#daryl hannah#beverly d'angelo#80s movies#80s nostalgia#comedy horror#cinéma#1980s movies#ghost movies#haunted#high spirits

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would any of you guys be good at identifying some black n white ghost movie i watched ages ago, but can't remember the name? I don't even know anymore, it's been driving me nuts hhkglfl

For anyone interested, here's what i remember:

This woman ends up as the caretaker for an old couple. They love her and basically adopt her (it's very sweet)

The caretaker starts getting possessed by who i wanna say was the old couple's daughter. If not daughter, than maybe original owner of the house?

The caretaker starts knowing how to play songs the ghost knew, and falls in love with a doctor i think? (Like the ghost's love interest was a doctor)

The caretaker gets sick or something, and iirc, the ghost's love interest shows up, also as a ghost, to help her move on. The fact he's a ghost kind of supposed to be a heavily implied twist.

Not too descriptive unfortunately. Some extra details tho: i wanna say the caretaker starts the movie in a train station. She's new to town. There's also a point where sge rides in a car and says how fast it is (it's going like 15mph)

#movies#old movies#ghosts#ghost movies#please I'm dying trying to remember it#it wasn't even my fav#it just bugs me since i can't for the life of me remember

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favourite Haunted Mansion character?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Folklore & Gothic Horror Short Films - Interview with Lucy Rose

Lucy Rose is an award-winning writer/director for screen and prose/nonfiction writer with an interest in gothic, girlhood, horror, and literary fiction. Her fiction and nonfiction have been published in Dread Central, Mslexia, and more.

Lucy is represented by Cathryn Summerhayes at Curtis Brown (Books)

Other enquiries to hello [@] lucyrosecreative [.] co [.] uk

Listen to the interview here/on your preferred podcast provider (search + follow Eldritch Girl: Weird Stuff and Nonsense)

Read the transcript off tumblr here or here

vimeo

Tip me if you can and you like this interview, it helps keep the podcast going!

Interview Transcript

CMR: Hello! Welcome back to Eldritch Girl! This is really exciting because we’ve got Lucy Rose who is a filmmaker, and we’re going to discuss the indie horror short, She Lives Alone. Lucy, would you like to introduce yourself?

LR: Hello, I am Lucy, I’m a filmmaker based in the northeast and I am the writer-director of She Lives Alone. She Lives Alone was such an amazing fun project to be able to work on. The development process was really fun. I worked really closely with my producer to explore the rural landscape of the place I grew up, which is a place in Cumbria. And I really just kind of wanted to bring a small facet of our Celtic regions and that tiny little culture to the screen and combine that with my love of Gothic horror and ghost stories and all the stories basically that I heard in Cumbria growing up that used to keep me up at night forever.

She Lives Alone has gone to some really cool festivals and it’s gone to some BAFTA and Oscar qualifying festivals, which is really intimidating but very cool. And then it ended its journey by winning best runner under 100 K at the Northeast Arts awards and getting picked up by Alter, which was the most amazing surprize in the whole world, because now it kind of finally gets to see its audience after a virtual festival runs so that’s lovely.

CMR: that’s so exciting I’m really happy, the whole film is about 15 minutes long and it is available on YouTube and so I’m gonna play a little bit of it I’m really excited about, which is kind of at the end, so I mean spoilers, but it is a ghost story, so you can kind of – I mean you can’t see it, you can just hear the audio. But we want to talk a little bit about the folklore behind it and a little bit of what’s going on, so we’re going to start from 11:41 so you get a sense of the music and the dialogue – it’s very much a monologue, isn’t it? A lot of it is a monologue because well… she lives alone.

[Laughter]

LR: Yeah.

CMR: it’s really dark and atmospheric and I think there’s maybe like two other characters in the whole film, which is like you know really cool. Okay, so. Let’s see how this let’s see how this works.

[clip plays from 11mins 46secs in: an adult woman with a low voice and Cumbrian accent is speaking. The line is “Bury you in earth, bury you in mud as thick as bark” over and over in hushed, desperate tones, with the tense score, whistling wind, and metallic clinking. There is a sharp scream and gasps at the end as the music swells ominously.]

youtube

CMR: Actually going to pause it there because that’s like a really good bit. I think the coolest image of that is the iron nail through the Bible through her hand which I was seeing as an exorcism ritual or part of an exorcism ritual, and can you tell us a little bit about that element and the little bit of dialogue that she’s got as a kind of mantra that is “Bury you in earth, bury you in mud as thick as bark”?

LR: And so I grew up in like the tiniest, tiniest village like. It may be had like six or seven houses. And it was so remote so if you wanted to go anywhere to like a shop you’re looking at least 25 minutes’ drive, and so the sense of isolation and because of that, like the Community, and what the Community felt like, and how we as people kind of used storytelling as a method within our like our tiny, tiny little culture that again – seven houses – I basically took things that I’d heard in my childhood and sort of morphed them and manifested them into this film.

I used to live by this woman who I will literally remember for the rest of my life, who was very superstitious, an extremely superstitious woman, and she was just the most incredible person and so like unashamedly weird. She was just so in touch with herself, which I think is so difficult in a small community, to be able to just like live your weirdness and like not care what people think of you, because everybody has opinions in those tiny little tight knit groups.

And she used to mess around with all sorts, but she you know she taught me like what ouija boards were and what voodoo dolls were, and she was really, really like spiritual and she often talked about like how connected to the earth and to the planet she felt was like a human, and I’d sometimes visit her after school. And I’d sit in a kitchen, while she was cooking dinner, for I was burned, and she just seeing these like really weird songs that she just made up herself like these little folk tunes. I just pulled phrases and lines and words that she was saying, because she did – she – I think she was just sort of… in hindsight, as a grown woman, I think I see her loneliness now, and how that connection to the earth and to nature was something that really, really kept her from going insane.

And it was a sort of gravity to her and that’s kind of what I wanted to give to Maud was this sense of like you might be without a person or people but you’re not on your own, and you can always rely on different spiritual things to sort of find your centre and in terms of the Bible, the nail going through her hand, I think it’s really metaphorical but I really just wanted to talk about the power that was kind of harnessing her, and the struggle between how her mum was treating her. So, for context, people [listening] if you haven’t seen it, Maud lives alone that’s the “she” in She Lives Alone. Her mum’s just passed away and she’s basically like in this normal grieving period and she begins to realize that she’s haunted by the spirit of her mother and her mother left her one thing which was the Bible, and it was because the mother always thought she was a wicked girl.

Basically, at the end film she casts out the spirit of her mum by bonding herself to this Bible, like physically binding herself to it, and I think it’s in part a metaphor about… I think in terms of discussing themes like trauma, like that trauma is always going to be a part of you. You can’t separate them, like, they’re together, and that’s horrible, but I don’t think that that’s a bad thing. I think it’s like an acceptance that like it’s just one of the bags you’re carrying with you in your life, and one of the items that you keep with you, and it doesn’t make you an awful person, it’s just something you’ve got in you.

And in a more sort of physical sense like, for me, like one of the staples of rural life is cast iron. You see it everywhere, you see it made making the gates, making the beds, making the keys, the locks, everything.

So I think it’s just bringing that industry and that sense of objects having a space in our community, and it sounds ridiculous, but one of the other things is the red stone and you constantly see some stone in in Cumbria, it’s everywhere you go and all the houses are made out of it.

And everything is red and orange and rust and copper coloured so it’s just one of those things about like bringing the identity of the land and the place and the people, whether that’s the minerals, the materials and the industry and embedding it in the world of the film, so that it feels real and also acknowledging the spirituality of the place so like, the folk song that is in the film…

Acknowledging that however small the culture is, it doesn’t mean it’s not important, and like that folklore, I think is a hugely, hugely important staple of that place and I just really wanted to like bring that to life in this in this film.

I think it works really well like and I also like the detail when she draws, um, so she has the Bible in the palm of your hand and then she draws a diamond on the front of the Bible around the Cross. Is that from something or is that a detail that organically came about, or is that based in folklore?

LR: And so, one of the things that came from, that sort of like rhombus square shape, is the woman who used to live next to me – again this incredibly spiritual woman who I, like, everything I learned about our tiny culture I learned from this person.

And, and she used to make these like… they were like twigs that you’d like put into squares and then you put different twines around them.

You know one day it’d be like fishing twine that she … her husband used to fish a lot, so she’d take some of his fishing twine, and she’d make these little rhombus shapes, I can’t do it like that. [shows me with her fingers in a rhombus shape]

And, and she put little flowers in them and she used to just leave them around house, I was never quite sure what they were, but she always used to call them wishing hexes.

She’d just leave them around and they were to bring good fortune and it was really beautiful, it’s really beautiful.

CMR: Oh that’s really interesting I like that melding of that kind of folk tradition and then Christianity and then like, different spiritualities is that you get kind of melded in a place like that.

LR: And I find that that’s a truth though, isn’t it, I think a lot of people find spirituality and no one person’s version of any faith is the same, and that’s something that’s actually quite beautiful and that’s born of our experiences.

CMR: Yes, and I think it’s a flavour of folk Christianity as well because, like I think it’s become… from outside perspectives I think it’s a very homogenous religion or a very homogenous spirituality and I think a lot of that is due to, you know, perceptions of modern evangelicalism and that kind of thing. But I think you’re right, in different enclaves people still do have their own traditions.

And it’s really – it’s really cool to see that because it’s a period drama as well, this film, so it’s linking back to a kind of earlier age and an earlier kind of expression of Christianity and folk Christianity, but also, I mean, did you have a year that it was set in, or was it just general?

LR: So I imagine it’s set in mid 1850s but, like the year is quite vague.

But I think like one of… actually, speaking of time, one of the really fun aspects of the film is that where it’s based has such an interesting relationship with time. Cumbria, when you look into its background, it’s wild. It’s been constantly fought over, so its identity is like a complete mishmash of different cultures from like Norway to Roman to old Old English, to everything. There’s Germanic in there, and it’s absolutely insane.

And so I think that sense of time, and even though it’s a period drama, one of the things we tried to create was the sense of timelessness to it so it almost exists in its own pocket?

CMR: Yeah.

LR: And that was like really crucial for us because we just wanted… What we kind of imagined when we sat and we thought of as a creative team, we were like maybe this is what it felt like because it was so disconnected and its culture was so constantly changing and evolving and adapting new ideas from like people who came and left or people who conquered and then were defeated and… yeah.

CMR: I think that works really well in the film because you’ve got it centred only on two locations which is her cottage which is miles from anywhere so a friend from the village actually comes to visit her, but you never see the village and you don’t see it through her eyes, you don’t see it through her friends eyes, you don’t see any other people at all. you’re in, and you have a sense that the village is quite a walk away so she has to travel to get in there, however long that takes and it’s just this idea of… there’s no civilization that kind of thing, and even the civilization, that there is it’s obviously not urbanized and it’s obviously like quite far from any kind of urban centre so you’ve already got that kind of thing going on, and the cottage itself is this is where the horror is. That’s the locus of the domestic horror, because the spirit of the mother is haunting her in the house.

And so the other place you see her is just on the moors or you know that ring of standing stones isn’t it that she’s in.

LR: In yeah. The standing stones were actually based on a real place. We really, really wanted to shoot in the place, but we couldn’t because it’s an active spiritual site and it just wouldn’t be ethical to shoot there.

But the standing stones are based on a real stone circle called Long Meg and her Daughters.

And, which is place I used to visit all the time, and when you go now it’s just the most beautiful place, it’s in the middle of nowhere, there’s like ribbons in the trees, bells, and it’s just stunning, but I mean that sense of isolation is like. I think, with it being a short film, you can, from a boring technical perspective, you can explore those worlds, but I wouldn’t want to do that anyway, like I think it’s I really like just as a personal preference to how I approach things, again, going back to that word like pockets, I really like to capture like small pockets of hidden histories, quiet tragedies that don’t necessarily get written down in the history books, because they’re not deemed important enough to write down.

And when we think about period dramas which we think of like glitzy giant polished glossy manor houses, sweeping romances, like you know, especially with like the massive Bridgerton fad that’s going around at the minute, you don’t think of the real people and the very real lives and consequences and events and you know, there’s hidden pockets of laughter with one person to another and realizing that ‘oh my God that’s my that’s my partner and I’m going to spend my life with them’ or, you know, ‘I hate my sister because she’s the worst person in the world’, but they had to share a bed, because they had no money.

It’s those like really tiny moments that I tried to catch on to because they’re just not explored enough, but I think it really serves horror because horror’s everything we fear as a society.

And I think you know, I think, in some ways, like rural communities, the way that they’re treated within our society is odd. You often hear them referred to as sheep shaggers or whatever, or like farmers, and that comes with the added like a sort of thing of like well they’re not clever enough to have an opinion on this or that, but then on the flip side, though those communities are also beloved for their influence on things like literature, from like every genre you know from you Beatrix Potter to you know, everyone else, so it’s a really – I think that’s sort of push and pull, and those two opposites can create real conflict, which is why it serves horror so well, because you kind of have to address those conflicts within the subtext of whatever you’re making.

Can’t remember where I was going with that. Just monologuing about justice.

[Laughter]

CMR: Yes, but that’s it isn’t it, because you’ve got like – rural communities do have those polarized perspectives, that they either idealized and it’s like this pastoral idyll before urbanization when everything was perfect, or exploited because of the natural minerals you know, so you’ve got things like the South Wales coalfield, which is where I grew up, and there’s huge chunks taken out of the landscape there’s massive scars on the mountains from the quarries.

And then dying communities exist because they were only there for the mines and now there’s no mines and there’s no reason for those communities to exist.

And people are like, well the community just shouldn’t exist, you should all just go somewhere else. Where are they going to go? You know, I get very annoyed about that because, yes, it’s you know, there are communities that exist and they have their own identities, they have their own deep roots in that place and that sense of place both traps them there and anchors them there at the same time.

I think you get that in this film as well, that sense of both entrapment and anchorage comes across in like she won’t leave the cottage because you haven’t got anywhere else to go. Like, that’s all she’s got, she’s not going to… what are you going to do, move to the city? With what money?

LR: You know it’s true it’s I mean everything you’ve just said it like chef’s kiss, by the way, five stars.

I was just like, yes.

I would listen to a podcast just about that, but you’re so right, and I think you know, I was talking about this.

But I think it’s that split thing we have as humans, where our bodies want to be connected to nature but that’s what we want in our bodies, in our bones, in our fibres, but our brains are like … I want capitalism!! So you’re stuck in the middle, like I don’t know where to go, and I’ve already said this, [laughs] the middle ground is Animal Crossing, because you get that like relaxed beautiful countryside, but you’re doing it through capitalism.

[Laughter]

CMR: yeah it’s difficult as well to see it from a 19th century working class perspective which obviously we are so divorced from now that we have to see it through the filters and the lenses that we bring to it, because everyone sees things through the lens of their own culture, whether you think you do or not, right, so it’s a really interesting exercise in just looking at a little bubble, a little bit, like a pocket of time.

And, and what I love about it as well, is that that quiet domestic drama that we haven’t seen, but you start to fill in the gaps for yourself, because a lot of it is the silence and the things that she is not saying, and particularly in the dialogue when her friend comes to visit her, and it’s like Oh, where have you been and she’s like Oh, you know I’ve been here, living my life. Except she hasn’t been, because she’s been stuck in the house on her own, her mum’s dead, and then I think that’s when you get the sense that that space of grief and absence is the time when she’s actually starting to realize how shitty her mother was to her.

When you’re going through it and living it and you don’t have any other options but to stay in your situation, you can’t go anywhere because there’s nowhere to go and you have no means to go anywhere and everyone in the village in a community like that anchors you to that community, because they’re the only people that you know, but also you feel like you have these senses of duty and responsibility to your mother. But that sense, as well, is imposed upon you by other people who think that you do [have a responsibility/duty], right.

[People] that you’ve grown up with, and so you have to answer to everybody in that community based on your choices as well, and she obviously doesn’t want to do that later on.

Not for any bad reason but it’s just she’s like seems like a very introverted kind of character, who doesn’t have that ability potentially to stand up for herself. And you kind of get the impression that’s very much the mother’s fault.

But yeah, and this idea that she’s wicked as the mother is constantly telling her that she’s wicked and then at the end you get that realization of “you always said I was wicked but it wasn’t me it was you”, and the only time she could have said that is when her mother is dead.

LR: I know it’s sad isn’t it.

CMR: Yeah. Just crying here [laughs] like oh my God.

LR: Yeah. It’s like justice but it’s not the justice she deserves. I think. And that’s… which is what makes it horror, and it’s also what makes it true, right, like it’s so sad, and I think it’s – do you know, one of the things I always talk about this, but I think it’s so, so true and I think if we all just looked at this and acknowledged it, it would really change the way we think about how we express ourselves as humans.

I think, obviously, as a culture, as a society, as a civilization, we’ve picked up bits and pieces of our history and we’ve those are the bits that survived that’s what we are now, and I think the bedrock of what we’re doing at the minute is extremely Victorian, which is why I call it a Gothic piece, even though it’s not got the big manor house and, like, the two orphaned children.

But I think that’s why I call it a Gothic piece, because I think in terms of what it’s trying to say about us as humans now, like we are most directly linked to that time where Capitalism became everything, like mass production, science, medicine, industrialism, all of these new things that started changing the way we experience the world.

Things that kickstarted technology to a new level, things that opened the door to expression, conversation, like newspapers were selling more, books were selling more, people were experiencing new perspectives whether they liked those or disliked them, you know, and I think it’s that thing of expression, like now, when you put a parallel to that.

And you talked about like how quiet she was how she never said says what she thinks, and I think, you know, like especially like we didn’t make that film in lockdown. That was a pre COVID film, it was written years before COVID and it is just by chance that, like, everything that we experience when it comes to human expression was just absolutely amplified during the COVID lockdowns. So like, when we look at how we communicate our lives, especially on things like social media, I know it sounds corny, but we never say what we really think.

I think, you know, when people are getting… even when people appear to be saying what they think when they’re being reactionary on Twitter or getting triggered by an opinion and saying something because they just need to get the anger out, like I think they’re not saying what they actually think because they’re reacting to something that’s triggering them and they’re not talking about the trigger. They’re talking about why they’re angry about the thing that they’ve been triggered by.

And likewise, on the other side of that spectrum we’ve got like you know people who thrived in lockdown: I’m doing this, I’m doing this wellness masterclass, but really we were all struggling you know, and I think that’s what Maud’s experiences is just that, like, a journey of learning to express herself, learning to get the words out, the real words, the ones she’s actually thinking and not just what she’s been told is acceptable to put out there and to let out of her mouth, and you know, I think that that really links to the Gothic because it’s all about you know repressed desire, whether that desire is for like a person or expression, you know.

CMR: Yeah definitely and I think…Yeah there’s so much, I mean that there’s that kind of sense of Gothic isolation as well, like we talked a lot about that and also like the… I guess the fracturing of your identity and the rediscovery of your identity, which Maud kind of goes through on this really short journey, but it’s a very intense journey that we kind of go on with her and you’ve got that sense of that really intense time of grief and coming to terms with, not just the death of her mother, but also grieving for potentially the person that she could have been.

LR: yeah.

CMR: Which she’s only just coming to terms with, and that’s also kind of like a haunting for Maud as well, that kind of the you know, that the spirit of the mother is what we decide is haunting her and then at the end is like the reveal of the you know the actual spirit itself that you see, just very kind of Woman in Black-esque which I love.

But you also get like this… I love the fact also that she was also in mourning dress, the mother and presumably you know her husband’s dead and that’s why it’s just her and her daughter but you get this dour woman who was sunk in her own grief and that has been haunting Maud also, like her mother’s emotional absence, you know, through her life.

But what’s actually haunting Maud isn’t just the mother.

It’s a lot of things.

And so you get that kind of rejection and you know that that she tries to reject all of that and bind herself to something positive, and cast out that spirit, but it’s not easy to do and I keep coming back to The Babadook in my head because it’s something that you can’t get away from.

LR: Yeah.

CMR: The babadook as a metaphor for grief, you can kind of lock it up somewhere in a room and look at it and kind of acknowledge it’s there and make sure that it doesn’t hurt anyone else, and that you don’t… you know, you don’t lash out and you don’t let it escape and damage or fracture relationships, and you do that by acknowledging its presence and dealing with it in a mature way, and by communicating with other people about it. Otherwise it gets in the way of your relationships. Which, for me, was what that film was about, in particular, between the mother and son [in The Babadook].

Here it’s Maud. Almost as if there’s like a hint at the end that she doesn’t succeed in that, because it almost overpowers her. So I’m going to spoil it a bit, but I think these aren’t spoilers, these are more like reasons for you to watch the film.

[Laughter]

I think if I could explain the whole film and then you wouldn’t want to watch it, like, I don’t understand you.

[Laughter]

So yeah. So there’s a bit… so after she’s sort of nailed her hand to the Bible, the nail then comes out of her hand, and it sort of levitates, and it’s almost like the iron is… it’s almost like a rejection of her or a rejection of what she’s trying to do, that, that bond doesn’t work.

And that’s kind of like, oh is she a which you know, because that sign of cold iron not being compatible with the person of a witch or a fairy or something like that you know you’ve got that kind of link to it, which I thought was really cool, but you also have the mother standing there, the mother’s ghost is in the frame behind her where she can’t see it, but kind of looming over the proceedings, and you’ve got this sense of like what exactly is…[happening]?

Is the mother causing the rejection to happen, and is it the rejection this you know the physical rejection of the nail, but it’s that kind of… that [haunting/grief/trauma] isn’t going to be healed by a ritual.

LR: yeah.

CMR: That whole thing is not going to be healed by a moment in time. Even, no matter how grounded you are to the place you’re in, no matter how well thought out that ritual is, no matter how desperate you are, that is a process that is going to take years and she is always going to be haunted by numerous layers of things that have come out as a result of her relationship with her mother, so, in a sense, her mother is always going to be there, whether her spirit is physically present or not.

And that’s kind of the end of the film, it is very ambiguous and quite chilling, because you get that sense that it’s not – it’s not over, it’s not going to be over and that Maud’s haunting is kind of something she’s going to have to live with – or not – and that’s… that’s the difficulty of living with grief isn’t it, that for me that was very kind of relatable and very powerful and I really appreciated the whole tone of it, and I was like oh God yeah that was very upsetting as well, really upsetting to think about.

But I think that’s like you say there’s not a lot of space in a lot of kind of glitzy period dramas that are more about the romance and the upper classes, to look at working class tragedy, and you know, the ordinary people and those pockets of normal domestic drama, and how they deeply impact someone.

LR: For sure. I think more like more biggest tragedy is that it’s… You know, the ghost is never going to go, she’s just going to learn how to live around it, and you did that thing, that’s kind of how that grief and that trauma works, and I think another thing that’s quite sad about these experiences, is that, like, you can look at something ugly, whether that’s an experience or person and it’s really hard to accept that person as a complex human being with their own troubles, because I think one of the hardest things to admit, and it’s something you touched on, actually, is like, when you think about the mother’s character and how she’s in mourning dress, she’s lost her husband, she’s got a lot going on in her mind, and I think one of the things that Maud can look at is the fact that, like it doesn’t make it okay, and it doesn’t make it acceptable what this woman has done to her, but like pain recycles into pain so often. It’s horrible and I wish it didn’t do that, but it does, it punches down and it punches down, and it keeps going, and keeps going, until someone strong enough to go, Nope, not anymore, and it’s so hard.

Whether Maud does that remains to be seen at the moment because I think it’s that’s another journey. Just looking at it is the first step isn’t it, and then dealing with it in in all its complexity, in everything that it carries with it that’s like a whole other beast like it’s just so much.

But I think you know, like in terms of like the working class aspect like one of the things that just became so apparent to me when I was doing my family tree. So I grew up in Cumbria, but my family are all from Yorkshire and I realized, none of us really had left Yorkshire since the 1500s, that’s what I discovered, and we’d always been in like areas like Sheffield and Huddersfield.

Well, I think what’s so sad is when you look at some of the family trees on like all of these research websites, they have photographs, they have items, they have diary entries they have pieces of those people.

And I still think I’m lucky, a lot of people don’t have names, but I just have a list of names. I don’t have church records, I have a couple of sentences that I found.

And I just think that’s so awful that like, we’ve deemed that some people are worthy of being remembered, some people are not, I just find that like horrifying and that’s, you know, like, oh God.

CMR: yeah I taught a family history course a while back, and it was it’s really hard when you’ve got like very limited things to go on.

And one of those things is the access, which people I think take for granted now and don’t realize, but the accessibility of things like photographs.

You had to save up for those and maybe there was only one you know one shop in the town that was like three towns over so that’s a whole day of it and you have to take that day off work and you can’t take days off work because that’s not how it works.

If you’re running a farm you can’t just go off.

LR: yeah.

CMR: You know, never mind about the cows today, love, we’re having our photograph taken like.

LR: You can’t just book in some holiday.

CMR: yeah so it’s like it’s a very… It becomes a very lower middle class – aspiring middle class – kind of thing, but a very middle class kind of thing to have a photograph taken.

But also at least in Wales, you had to pay for a church service but you didn’t have to pay to have your relationship blessed on the church steps. So there was a lot of… so you won’t have parish records of those blessings for the relationship, because those relationships were not technically legally “marriage”.

LR: Wow.

CMR: So in Wales like I know somebody was doing his family tree, he’s retired and he was doing it as a thing you know, and he realized, he was the first legitimate child in about 200 years.

LR: Oh my gosh, that’s insane.

CMR: And the reason was that it was just too expensive for people to get married so they would that they used to do a thing, where they would take take on the name, Mrs., the epithet and say that they were Mrs Jones. But they never legally changed it and they never legally had the marriage certificate to prove that. They just had, you know, they just moved in with their partner took on Mrs as an epithet and then had the children and the children will have the husband’s name and everyone just worked around it as if they were married, and that that’s a lot more common than people think. It was, you know, a lot more widespread, especially if you were poor. And that’s why it’s really hard to find a lot of the records, but also just the accessibility of things like weddings, things like, you know, things that would leave that indelible mark.

LR: You know it’s honestly insane to me like I think it’s it’s just I think that’s where a lot of load my characters come from even like I don’t have any family called Maud, but I look at a name on a piece of paper, and all I have is letters, and I’m like, who are you? What did you look like? Was your hair brown like mine, did you have the same sense of humour as me? Like, just trying to really untangle something that you have no information on, and I think it’s just that…it’s just that thing of, like, there are so many humans on this planet, many like millions millions millions, and you know, and just trying to find a way to like honour every life, even if it was small, and I think… God what you’ve said blown my mind.

CMR: I’m not sure how prevalent it was in England or different parts of England, but um yeah that’s certainly the case in a particular area of Wales anyway.

[Takes a breath to get back on track!]

CMR: I wanted to talk about the aesthetic of it as well because you’ve got this it opens with that and see and see if it opens with her on her knees on the moors digging earth up. You use such a lot of muted colours and muted tones is that, like, was that a conscious decision from the standpoint of we want this to be Gothic and we want, we want it to look like this, or was that something organic or how did that kind of work out for you?

LR: And so I work super, super closely with my DP [Director of Photography], Lizzie Gilholme, she was amazing, I think she’s the best cinematographer in the world, I might be a little bit biased, but I do I think she’s incredible and so a lot of the time you give a script to a DP quite late on, but I literally from the conception of the very idea before it’s written down I WhatsApp Lizzie, and I’m like “Hey, I’ve got this idea, I want to know what you think”.

So she’s there from day dot and she, bless her, like she shouldn’t have to, she reads so many drafts and she really does see a project folder from like you know, bare bones to like the fully fleshed form that it ends up in.

And, but me and Lizzie like we talked for a really long time about how we wanted this film to look we watched loads and loads of different movies that we really loved.

But I think the main, in terms of like creating an aesthetic, building a world, like our main thing was like we want this to feel like it felt for Maud so.

The muted colours and the sort of like the mauves and the browns and the muted greens, like those are all colours she would have experienced and those are the colours of her world.

And even down to like how much light we use so this film it’s very dark like extremely dark and you’ve really got to watch what’s going on, but it’s because they didn’t have that much light. If you got up in the middle of the night you’d go to the embers of the fire, you’d light a single candle, and that’s all you had to see in the house, especially if you didn’t have gas lamps, so we really wanted to bring that sense of her world and her, her everyday experiences, in terms of what she saw what she felt.

Even the music, that was like… The woman I worked with was called Die Hexen who is an incredible Irish composer just has the most beautiful mind, and it was super important for me to go to find somebody who lived in a Celtic region, because obviously, Cornwall through Wales up through Ireland and then like at the top strip of England and Scotland, like those are the Celtic regions, and like I don’t want that piece of that culture to be lost on the film, so it’s really important to me, to find somebody from those regions.

Die was, you know, luckily she was like I really like this project, and I want to work with you and I was like, amazing, and the first thing I said to her was, I wasn’t super particular in terms of what I wanted. I didn’t send her any music I liked I was just like, this is what you need to know about this film. And I said it’s about trauma and I really want that to be present in the score.

But, most importantly, one of the main sounds that you hear in Cumbria is the sound of the Helm Wind, which is a specific type of wind crafted by the shape of the valleys.

And it’s this really high pitch whistle, but it is so strong it can like literally pull the roofs off of houses, it’s just fierce. And I just said to her that I want that, like I want that sense of like, it’s, it’s flowing past you, and you just have to keep yourself standing up.

And, and I mean she came back with the most incredible score that I’ve ever heard in my life, and I literally think I heard one note, and that was it, and then we were done, and I don’t – I don’t think that happens.

But um, you know there’s some – even in the quiet moments where like the score isn’t central to the scene, you hear that whistle. And that’s something that’s all the way through, and it is just that sense of creating Maud’s world.

I love the Gothic, and folklore, and I’m obviously influenced by those things, but it just so happens that they were central to Maud’s day-to-day existence, and that’s why it came through in those creative choices, because she demanded it to be that way, and I couldn’t say no.

CMR: I think it really works I love it, I think the music is so good, it really adds to the drama of it and also like it’s just got that right balance. It’s creepy but it’s yeah and that whistle tone-!

LR: It’s chilling.

CMR: Yeah, it is chilling yeah, it very much… yes, that sense of isolation and nature and just being buffeted and existing in this kind of world that she – because she’s very much on the cusp of that industrial world in the mid 1800s but also she’s embedded in the past as well, and like where you get that sense of the Standing Stones scene and the wild moors and that kind of thing, that she’s trapped by the past of the landscape as much as by her own past, as much as by her family’s history, and yeah I think that and the music just works so well with it and the colours and the, the, you know, just that sense of darkness.

LR: very dark very, very dark.

[Laughter]

CMR: I really loved it and I would recommend everyone watch it and I’m gonna put the link in the transcript so everyone can see it, I might actually embed it in the blog post so everyone can watch it.

Do you have anything that you want to plug while you’re here or any other projects that you’ve already made that you want to tell people about go for it.

LR: So I’m currently in post production my next film, which is definitely more identifiably Gothic with the big house, the big spooky house, creepy hallways and I’m really, really excited by it, it’s kind of honestly I’ve been working on this short film script for years so it’s really nice to see it actually exist and we’re really, really excited about it, where we’re on we’re really, really, I think we’re really close to picture lock it now, but my producer will slap me on the wrist for saying that.

It’s looking so, so good, we’re so fucking proud of it and and everybody who worked on it just worked so hard so I just they are, they are the best. Thank you if you’re listening to this.

But other than that, we’re developing our feature film as well, which is very …

CMR: [gasps and claps]

LR: I know and it’s somewhere between like She Lives Alone and, like the sort of more Gothic leaning “Taste”, which is the film that’s in post-production, so it’s kind of like a nice little lovechild between those two which I’m really, really excited about and it’s also based off a local folklore called the Croglin Vampire.

CMR: Oh, my God.

LR: I know, I’m really excited, so if anyone’s listening, please manifest like crazy, so that we can make it.

CMR: Is there a kickstarter any kind of… can anyone contribute or?

LR: No…

CMR: You’re doing it via grants and things right?

LR: Hopefully, yeah so. We’ve just finished a talent lab called Edinburgh Talent Lab Connects, which was a year long program with an amazing woman called Kate Leys, and also we got a mentor who was incredible.

And we’re hoping to move from treatment stage to draft stage next and it’s quite a slow process because with larger projects it just takes so much longer to really refine the story, but I think you’ll really like it, I hope you like it.

[Laughter]

CMR: I’m pretty sure that I will like it.

[Laughter]

LR: But other than that I’m just vibing you know, and manifesting like hell.

CMR: I think that’s enough though isn’t it. Like pre production and then a feature film is a hell of a lot of work.

Yeah I’m so happy I’m so excited for that. I can’t wait. So everyone watch the space. Go follow Lucy on Twitter.

LR: Please do, I post hilarious memes.

CMR: Yeah.

LR: Oh thank you so much for having me on, I’ve genuinely loved this conversation.

CMR: Feel free to come back anytime.

LR: I’ll be knocking on your door.

CMR: Obviously excited to watch the films that you’ve got coming out. Just really, really thrilled for you, so yeah lots of manifestation.

CMR: And that’s all we’ve got time for, so thank you very much for listening and we will see you again next week bye now.

LR: Bye!

#long reads#filmmaking#gothic horror#ghost movies#interview#lucy rose#creepy folklore#folklore#cumbria#dark folklore#Vimeo#Youtube

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

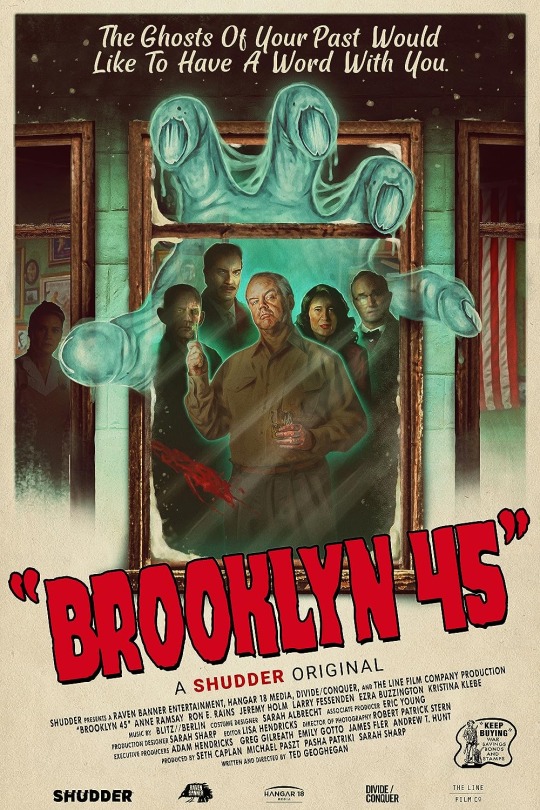

Brooklyn 45 is a great little bottled locked room deliberation over the ghosts of war, and also there are ghosts. I love a movie where everyone is like 50. Love a seance movie too.

#halloween hundred#halloween hundreds#halloween#horror movies#halloween movie#horror film#horror#ghost movies#seance movies#brooklyn 45#shudder

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you want a rec for a classic ghost story:

The Uninvited (1944)

My mom had taped this on a VHS when she was younger and of course my sister and I were obsessed with it. Perhaps one of my first horror films when I was 4? 5? Still holds up. Still get literal chills. 11/10 watch in the dark alone and get absorbed in the atmosphere it draws you in. It’s one of my top three.

Part 1:

dailymotion

Part 2:

dailymotion

#horror#classic ghost story#movies#ghost movies#I realize there’s not a lot of options to watch it so I included a link for the best place I could find :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On February 8, 1980, The Fog debuted in the United States.

#the fog#john carpenter#adrienne barbeau#hal holbrook#jamie lee curtis#horror movies#horror#tcm underground#indie horror#ghost movies#supernatural horror#movie art#art#drawing#movie history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

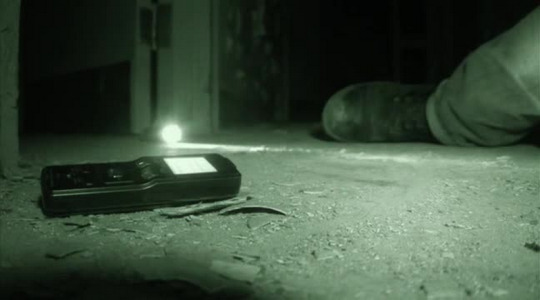

Sanatorium (2013)

A found-footage paranormal investigation movie that doesn't really do much new. Instead it just executes the basics of that particular nanogenre extremely well. The setting is creepy and they do a good job building up the tension with some great payoffs. Most importantly, it is overall very restrained with what it does show, instead of just showing something because they can. It's also a bit more graphically violent than other similar movies, which really makes the danger feel a little more real.

7/10

#hauntings#found footage#2010s#horror#horror movies#2010s horror#ghost movies#hospital#recommended#sanitorium

13 notes

·

View notes