#early life of buddha

Note

First of all, I would like to say that I love your art! 🥺💕

Second, can I request how Buddha, Poseidon, and Hades would react if the (gn) reader teases them under the table in the middle of the gods meeting? ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

Thanks in advance because I know I'm going to love what you're going to write.🛐

You're really sweet anon☀️❤️ comments like this really melts my heart and lights up my rainy days💞 I really hope I did a good job, sorry if it's not good🙏

RoR characters being teased by their s/o under the table!

BUDDHA

🍬Okay, Buddha really didn't want to go to that meeting. But you forced him to go: it's been some time now that you've had the intention of spicing up your love life, something more risky, exciting. Buddha knows how to be lazy when he wants and often you have to keep the libido high, it was time to teach him a good lesson.

🍬Buddha always sits in the back, dark seats whenever the gods have one of their big gatherings: he doesn't want to stand out and wants to nibble on his snacks in peace. But not that day...poor Buddha didn't even know what he was getting into...

🍬You sat on his lap, your place of honor, eating a candy you'd stolen from your lover without showing up. Buddha wasn't entirely interested: he kept yawning, throwing some paper at the head of the minor deities, in short, the usual. But not for long. It wasn't too long before you shifted your position to straddle him directly. "What are you doing, bunny?" he will ask you, intrigued.

🍬His response came when your hips started to move slightly, using the excuse of getting comfortable. For a second, Buddha's eyes darted around him to see if anyone was watching, and then he thanked himself for choosing a fairly secluded spot; so, she decided to relax and let you do it, even though it was nearly impossible to hold back the moans.

🍬"Little bunny...someone may see us..." he whispers in your ear, breath hot and short against your skin. But in reality, he didn't mind being caught, on the contrary, perhaps the idea of being seen would prompt him to give the gods one last slap in the face, bragging about his fun with a grin, as his hands rest lazily on your hips.

POSEIDON

🌊The Zeus of the Sea had already left the temple annoyed: meetings between the gods were never one of his favorite ways to spend the day, especially if it meant enduring the shouts of the noisiest deities. You too seemed bored, especially given the judgment that others had of you, being a nymph and not a diety.

🌊Boredom was starting to set in, which wasn't showing up on the other Olympian deities, too busy arguing and gossiping among themselves to notice your arm moving slowly up and down under the table.

🌊Poseidon, sitting next to you, had his eyes closed, beautifully ignoring your soft hands wrapped around his penis; all he thought about was how long it will finish before you get tired. If you ignore her she will get tired, right? No, not this time.

🌊Your fingers danced gracefully, taking their time as they went up and down, again and again. Poseidon kept his eyes closed so as not to open wide them wide and glare at you, but what the hell were you even thinking? He hated performing romantic acts in public, even less sexual acts, but if he stopped you, the others would surely find out something's wrong.

🌊Once you return to his temple, as punishment the god won't even touch you with a finger, waiting for you to crawl back to him with an apology worthy of your crime. "Next time think about it twice, I won't repeat myself"

HADES

💀Hades sat serious, ethereal and focused on his throne. His gaze moved to everyone present, while he let his little brother Zeus take the reins of the meeting. The lords of Olympus had gathered as usual to discuss their realms; you and your husband had arrived early and Hades was about to turn around, before seeing his wife dive under the table.

💀He didn't even have time to ask you what you were doing, that the door of the huge hall swung completely open, announcing the entry of his precious brothers. Hades was shocked, but he pulled himself together instantly, sitting in his seat without saying anything to avoid embarrassing you. So, the king of the Underworld just decided to roll with it.

💀Everything was going well, at least until Hades felt the zipper of his pants come down. The god looked down, halfway between furious and frustrated, stiffening as your glittering eyes met his. He blushed noticeably as your lips began to leave soft kisses on his crotch and boxers, making him shiver slightly in anticipation.

💀"Brother Hades, are you all right?" asked Zeus, unaware of the other's difficulty in keeping silent. The king of Hellheim was biting his tongue, his cheeks were red and his breathing heavy, a light sigh sucked from his lips every time your lips massaged his cock; always leaving a trail of kisses behind. "Absolutely, dear brother..."

💀At the end of the meeting, Hades will forcefully pull you out from under the table, lay you down on the table and grab your wrists. His breathing heavy and his eyes misty with lust. "Did you enjoy yourself, little one? Such a cute face, but we'll have to work on that attitude of yours...bad ones deserves a punishment..."

#record of ragnarok#ror x reader#ror x you#request#snv x reader#snv x you#shuumatsu no valkyrie x reader#shuumatsu no valkyrie#snv hades#hades x reader#ror hades#record of ragnarok hades#ror poseidon#snv poseidon#poseidon x reader#poseidon#record of ragnarok poseidon#snv buddha#buddha x you#buddha x reader#ror buddha#record of ragnarok buddha

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tamamizu Monogatari, a unique love story

This article, unlike most of my recent longer pieces, was not planned in advance. I learned about the subject very recently, and instantly realized I absolutely have to introduce it to more people, the previously posted schedule be damned.

The Tale of Tamamizu (玉水物語, Tamamizu Monogatari) is a story about a fox turning into a human, but a rather unconventional one, filled with an unusual degree of sympathy for the eponymous protagonist and focused on a rather unique relationship. In addition to summarizing it in detail and explaining the possible inspirations behind it, I will also try to explain why the tale found a new life on social media as a, broadly speaking, lgbt narrative, and why I think there is a compelling case to be made for such an interpretation.

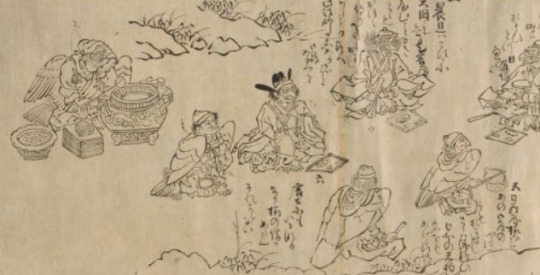

Unless stated otherwise, all images used through the article are taken from the Kyoto University Rare Materials Digital Archive, on whose website you can view scans of the original Tamamizu Monogatari.

The Tale of Tamamizu, also known as The Contest of Autumn Leaves (Momiji Awase) is an example of otogi-zōshi, illustrated prose narrative. The story was presumably originally composed in the Muromachi period (1335-1573), and it survives in multiple copies dated either to the early Edo period or to the end of the Japanese “middle ages” directly preceding it. The identity of the author (or authors) is unknown.

Despite its apparent popularity in the past, it seems no major studies of the tale of Tamamizu have ever been conducted. A streamlined translation (or rather an extensive summary) was published online by Kyoto University Library in 2001 and can be accessed here. In 2018, a full translation, as well as a brief introduction, were prepared for the anthology Monsters, Animals, and Other Worlds. A Collection of Short Medieval Japanese Tales. Still, it doesn't seem either sparked all that much interest in Tamamizu, despite the story’s obvious modern appeal.

Since the tale of Tamamizu is not well known, I will start with a detailed summary. I am consistently using female pronouns for Tamamizu after she transforms, as does the older translation. The other English translation switches between female and male pronouns. I will explain in the final paragraph of the article why I made the decision to follow the former.

The Tale of Tamamizu

The story of Tamamizu does not start with the eponymous character, but rather with a certain mr. Takayanagi from Toba. He is troubled, as while he is already 30, he has no children. He decides the only choice is to pray to gods and buddhas. This actually does work, and his wife becomes pregnant, and after the expected period gives birth to a daughter. She doesn’t get a name at any point in the story.

The girl’s birth is followed by a timeskip. As we learn, she was distinguished by twenty five features associated with beauty. This is apparently a reference to the belief that a buddha possessed thirty two specific physical traits; the number might have been altered to twenty five because of a popular group of twenty five bodhisattvas associated with Amida. By the time she reached the age of fifteen or so, she also developed great skill in composing poetry in both Japanese and Chinese. Her parents at some point decided that it would be ideal to send her to serve in the emperor’s court in the future.

The girl spends most of the time in awe of the blooming of flowers, the wind and other similar phenomena, as one would expect from a literary character of similar status. She maintains her own flower garden, and spends much of her time there.

On one of the days when she visited it alongside her friend Tsukisae, the daughter of her nurse, she caught the attention of a fox. The fox is, at this point in time, not yet Tamamizu. He wishes he could introduce himself to the girl. He considers the standard method - transforming into a nobleman - but he realizes this would likely sadden the girl’s parents, and would tarnish her reputation. He falls into despair. It does not exactly help that his attempts at visiting the garden again end up poorly - on the way there, he gets pelted with stones and then, after trying again, shot with an arrow. Still, he continued to hope to meet with the girl.

An opportunity finally arose through a lucky coincidence. Another family living in the same area had multiple sons, but no daughters, much to the parents chagrin. They loudly lamented that they wished they had at least one girl among the children. The fox overheard that and realized it might be an opportunity. He transformed himself into a teenage girl (curiously, the story specifically puts her at the exact same age as the unnamed second protagonist), and enters their house. She explains that she is an orphan, and while passing by she overheard the family’s woes. She offers to become their daughter. The couple instantly agrees.

The fox spends some time living with her adoptive family, though she gets sad easily and keeps bursting into tears. After some time, they offer that they will find her a husband in due time, but she reacts to that poorly, and eventually suggests she would prefer to become the servant of a noble lady. Her adoptive mother agrees this isn’t a bad idea, and reveals that her younger sister is a lady-in-waiting of the daughter of a local noble, mr. Takayanagi. She suggests the fox could become her attendant too. She is overjoyed at this prospect, and is soon sent to Takayanagi’s mansion to meet with his daughter.

The girl receives her new attendant warmly, and gives her a nickname, Tamamizu-no-mae (Tamamizu for short). They get along really well, and Tamamizu gets to partake in her various activities, serves her food and drinks, and even sleeps in the same bed (Tsukisae does too, though).

While Tamamizu does remarkably well as a human, some of her fox habits remain. Most notably, she is really afraid of dogs. Her lady sympathizes with her plight, and actually bans dogs from her household. This is a much welcome change from Tamamizu’s point of view, though apparently some other members of the staff start to view her as a coward because of this, and simultaneously resent her closeness with the girl.

The bond between Tamamizu and the girl reaches a new level when on a moonlight night they spontaneously compose a poem together. It deals with longing. We are told it was followed up by multiple other poems, which are not quoted in the story. Eventually the girl gets tired and heads to her room. However, Tamamizu remains outside gazing at the moon and eventually starts crying, unsure what fate awaits her. Tsukisae, who was inside all along, actually becomes concerned about Tamamizu, and says she feels sorry for her, correctly identifying the cause of her sorrow as love for an unidentified party. She shares her thoughts with their lady (in the form of a poem, of course). The latter summons Tamamizu inside, and soon all three go to bed together. Tamamizu is still overwhelmed by her feelings and can’t fall asleep, though.

Tamamizu continues to serve the girl for the next three years. She also remains in touch with her adoptive mother, who sends her letters and new clothes every now and then.

One day, many visitors arrived in the house for a friendly competition. The winner will be the person with the most beautiful collection of autumn leaves. Tamamizu decides she must find some for her mistress to give her an advantage. To accomplish that, at night for the first time in years she turns back into a fox, and leaves to visit her siblings. Not the adoptive ones, though.

As it turns out, she has two fox brothers, one younger and one older. She actually hasn’t visited them in so long they assumed she died and held funerary services for her in the meanwhile. They are overjoyed to learn that is not the case, and after learning about her current life agree to help her with finding unique leaves. She tells them to leave them on the veranda of her mistress’ mansion, and reassures them it’s safe for foxes to be there thanks to the earlier decision to not allow dogs on the premises.

After the visit Tamamizu returns home in her human form. Tsukisae and her mistress ask her where she has been, and she jokes about meeting with a “dubious fellow” (which, to be fair, is not even a lie, given the typical folkloric portrayal of foxes). This in turn leads to more jokes, revolving around Tamamizu no longer thinking about her mistress. She feels distressed by this suggestion.

Tamamizu’s brothers in the meanwhile succeed in their search for thrilling leaves. One of them found a branch with five-colored leaves decorated with the Lotus Sutra (as you probably know, one of the main religious texts in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition). Tamamizu is overjoyed, and instantly brings them to her mistress.

The girl received plenty of leaves from other people in the meanwhile, but all of them pale in comparison. She is so happy about the gift that she requests Tamamizu to also write poems meant to accompany the presentation of the collection. She protests that she is unsuitable, but eventually accepts this honor and gets down to work. The parents of the girl came along to watch her write, and both of them concluded she is exceptionally skilled. She ends up providing five poems, one for each color of leaves gathered. They are subsequently combined by these the girl wrote herself.

Obviously, the main characters’ joint entry wins the competition. This grants the girl such fame that the emperor declares she should come to his court. Since her father is not affluent enough to pay for traveling there, he bestows additional estates upon him to make that possible. Even Tamamizu gets her own estate, Kakuta in Settsu Province. However, she decides it will be for the best to give it to her adoptive parents.

Shortly after that, Tamamizu’s adoptive mother falls sick. She leaves her mistress to attend to her, but it did not help much and her condition kept worsening. Therefore, her stay had to be extended over and over again. This predicament worries her mistress, who sends her a letter to let her know that it is boring and gloomy without her around, and implores her to return as soon as her mother’s condition improves. Tsukisae is similarly concerned. Both of them voice their concerns through poems, which at this point should not be surprising for the reader.

Tamamizu of course appreciates these displays of sympathy, but she cannot return, so in response she only reassures both of them that she will meet with them again as soon as possible.

Shortly after that, the mother’s condition worsened yet again. The entire family laments through the entire day, but eventually everyone manages to fall asleep - save for Tamamizu.

In the middle of the night Tamamizu notices that an old, hairless fox entered the house. She quickly realizes that he was her paternal uncle (a fox uncle, that is. Not a relative of her adoptive parents). The illness was his doing, as she quickly realizes. Tamamizu requests him to leave her adoptive mother alone. However, the old fox says he cannot do that, as the illness is his act of revenge against her family, since her father killed his child. He concluded it is only right to make his daughter sick so that she dies too.

Tamamizu admits that this makes sense in theory, but she points out that acting upon desire for revenge will only bring bad karma, and bad karma from previous lives is why both of them were born as foxes in the first place. She offers the old fox a crash course in Buddhist ethics, and warns him that accumulating even more bad karma might lead to someone eventually killing him too, and to yet more rebirths in one of the three realms which are best to avoid (animals, hungry spirits, hell).

The old fox notes following buddhas is for humans, not for those born in other realms of rebirth (he’s not entirely wrong, humans are generally held to be in the optimal condition to seek enlightenment; animals must follow instinct and thus end up accumulating bad karma, devas are to preoccupied with celestial bliss), but eventually he relents and agrees that it would be wrong to kill the woman because of the actions of her father. He concludes that it would not even make him feel better, since his child would remain dead. He tells Tamamizu that evidently he was able to meet her because of good karma acquired in a past life, asks her to pray for his deceased child, and leaves, announcing he shall become a monk reciting nenbutsu from now on.

Tamamizu did what he asked for, and even performed a funerary service for her late cousin. With the problem solved, her adoptive mother returned to good health. She was therefore free to meet with her mistress again. She was elevated to the rank of chujo no kimi, the foremost among servants.

However, despite her mistress’ best efforts to make her feel appreciated, she was suffering from persistent bouts of melancholy. She wished she could confess her love and consummate the relationship, but she concluded that since she kept her identity secret for so long, it would be no longer possible to reveal it without losing the acceptance of the girl. She decides she must disappear. However, before that she prepares a long poem explaining her predicament.

She placed it in a box, and gave it to her mistress, explaining that it should only be opened if something happens to her. She then broke down in tears.

Tamamizu’s mistress does not fully understand what is happening, and asks if she perhaps is worried about their planned relocation to the imperial court. However, Tamamizu denies that and guarantees she will accompany her on the journey there. Her mistress starts crying too, and says she has hoped they will always be together.

Shortly after, the day of the journey came. Tamamizu’s mistress and mr. Takayanagi, now recognized as a lord, were certain that she went with them, but as soon as they reached their destination it turned out she was nowhere to be found. Days upon days of grieving followed.

Eventually, the girl realized that she had no choice but to open the box. From the poem contained within, she learned everything about Tamamizu, from the day they first met all the way up to the disappearance. It explained how she hoped to protect her mistress through her current life and beyond, but had to give up after realizing it was all in vain. In the final words of the poem, she firmly refers to her with the name she was given by the girl - Tamamizu.

The poem moves her deeply, but the story does not have a happy ending - we never learn what happened to Tamamizu afterwards.

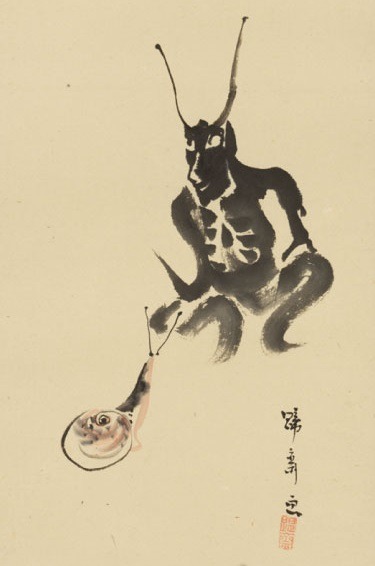

Tamamizu’s forerunners

It is agreed that much like the considerably more famous Tamamo no Mae, Tamamizu in part depends on earlier Chinese literature about foxes. Not exactly on the same sort of stories, though - she is not exactly a malevolent seductress, to put it lightly. The key to finding her forerunners is the scene in the beginning when the still nameless fox considers transforming into a male suitor at first, before settling on the form of a female attendant, and the erudition she displays through the story. An argument can be made that this is conscious engagement with a very specific type of older fox story, largely forgotten today.

In Tang China, fox stories enjoyed considerable popularity. You may remember that I mentioned this in passing a few months ago in another fox-themed article. One of the genres popular at the time was focused on fox suitors. There are many stories like that, but they largely follow a similar plot: a male fox falls in love with a human girl, takes the form of a dashing literatus and requests marriage. The girl’s family rejects the proposal, as despite charm and erudition the fox is ultimately an outsider with no family, and doesn’t depend on the well established institution of matchmaking. Afterwards, he typically tries to win the girl over with some sort of trick, and fails in the process, thus meeting his demise when his real identity is inevitably exposed.

In some cases, twists are introduced and the fox is effectively exploited by the family: for example, in the story about a certain mr. Hu (a common surname which is a homonym for the word for fox) and the granddaughter of the official Li Yuangong, the Li family agrees for the girl to be taught by the fox, and even asks him for advice on various matters, just to kill him once he outlived his usefulness.

Zhou Wenju's painting A Literary Garden (文苑图, Wenyuantu), showing a group of discouring Tang literati (wikimedia commons)

Many literati came from humble backgrounds, and only attained high positions thanks to success in the imperial examinations. However, their advances were often frowned upon by nobles, who saw them as upstarts. Therefore, faking a more notable origin was widespread to secure a better position in the high strata of society. All of this is reflected in the stories of the fox suitors. Xiaofei Kang, who wrote my favorite monograph about Chinese fox beliefs, notes that the stories might have effectively been a way to cope with everyday anxieties. In other words, perhaps the fox self insert fails so that the real person sharing his precarious status can succeed.

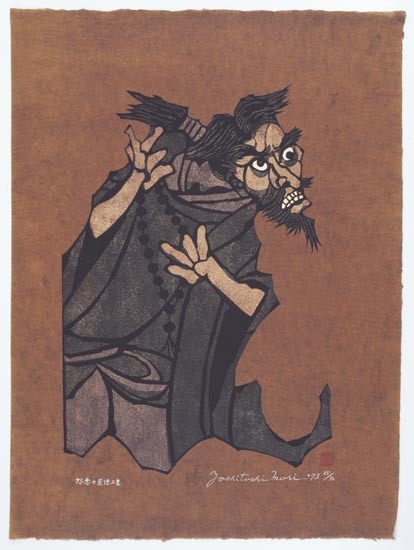

Another aspect of the Tale of Tamamizu which offers a clue about its origins is the focus on Buddhism, and its role in the lives of non-humans in particular. Tamamizu evidently attains a considerable familiarity with Buddhist doctrine, to the point the old fox basically seems to perceive her as thinking more like a human than a fox. Evidently, she doesn’t think being an animal should prevent one from seeking good karma. This seems to reflect a medieval Buddhist phenomenon.

Roughly from the Insei period (1086-1185) up to the eighteenth century, and especially between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, the dominant esoteric schools of Buddhism propagated the doctrine of hongaku (本覺), “original enlightenment”. This idea originates in an earlier Buddhis text, Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna. According to proponents of this idea all living beings, even plants, possessed an innate “Buddha nature”, as did natural features like mountains. They were innately capable of attaining enlightenment, or innately enlightened outright. Religion influences art, so it has been argued that the spread of new stories about animals behaving like people in the Muromachi period had a distinctly Buddhist dimension.

The modern reception of Tamamizu

Despite the fascinating themes of the story of Tamamizu, it only found a greater degree of modern recognition in 2019, outside of academic circles at that. I'm surprised it took so long, since when you think about it, the sensibilities of the author indeed seem surprisingly modern. The narrator even reassures us Tamamizu’s human form is the same age as the object of her affection, anticipating what sorts of shipping discourse could arise 700 years later.

Anyway, in 2019 a fragment of the story was the subject of one of the classical Japanese literature questions from the National Center Test for University Admissions, a standardized university entrance exam held across Japan each January from 1990 to 2020. This obviously exposed an enormous number of people to it, not just exam-takers.

Following this event, a Tamamizu fad seemingly swept social media and pixiv (curiously, there’s a single piece of art there which predates the phenomenon by six years; op actually updated the description in 2019 to say they are happy more people learned about the story). There’s even a Tamamizu Monogatari tag on Dynasty Scans as a result. It’s worth pointing out the wikipedia entry of the story was written in 2019 as well. Most curiously apparently a research project focused on Tamamizu, Kahoko Iguru’s Border transgression between species and gender as observed in “Tamamizu Monogatari”, received a grant in the same year too (source; more info here). It doesn’t seem the results have been published yet. I will keep you updated if that changes, obviously. I am actually surprised I didn’t notice the Tamamizu phenomenon back then, even though 2019 Antonia was distinctly more terminally online than 2023 Antonia is.

It’s worth noting that Tamamizu’s fame didn’t fade away. The online following the story gained was referenced in an Asahi Shimbun article a year later. A quick survey of social media will show you there are people still talking about Tamamizu today. People who aren’t me, that is.

What made Tamamizu so unexpectedly popular - arguably more than the story has been in the past few centuries - in recent years? Most of the linked sources relatively neutrally state that people perceive it as a “unique love story”. Social media posts are often considerably more direct: for many people, the appeal lies in the realization the Tale of Tamamizu is probably the closest to a lesbian love story in the entire corpus of medieval Japanese literature. I won’t deny this is in no small part its appeal for me too. Note this is not an universal sentiment by any means, though.

It is difficult to tell if this was the intent of the medieval author(s), of course. It is obviously impossible to deny that women attracted to women existed in medieval Japan, as is the case in every society since the dawn of history. However, they left little, if any, trace in textual sources. As pointed out by Bernard Faure, in Japan in the past as in many other historical societies “sexuality without men is properly unthinkable” and therefore received no coverage.

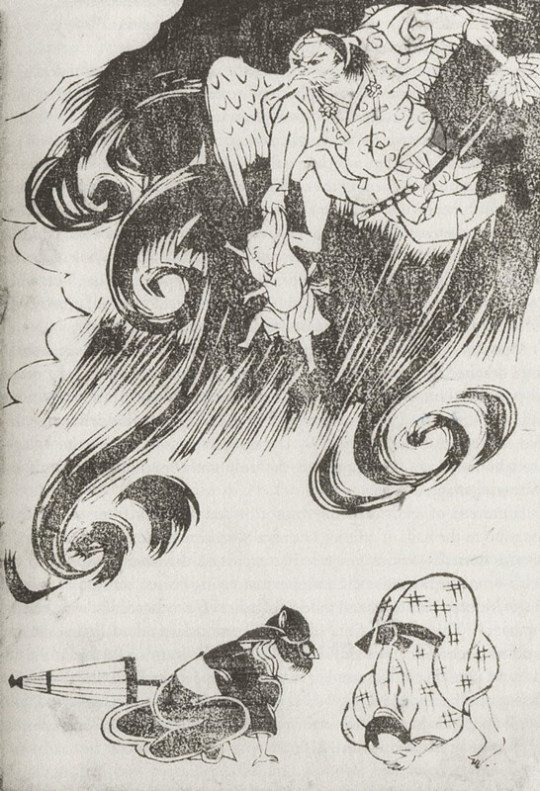

While there is plenty of Japanese Buddhist literature dealing with male homosexuality (trust me though, you do not want to read it; I’ve included a brief explanation why in the bibliography), there is basically nothing when it comes to women. The only possible exception is what some authors argue might be a medieval depiction of a lesbian couple in Tengu Zōshi, a work I plan to discuss in more detail next month, but note that this would be only an example of condemnation, since this work is a religious polemic dealing with vices of the clergy.

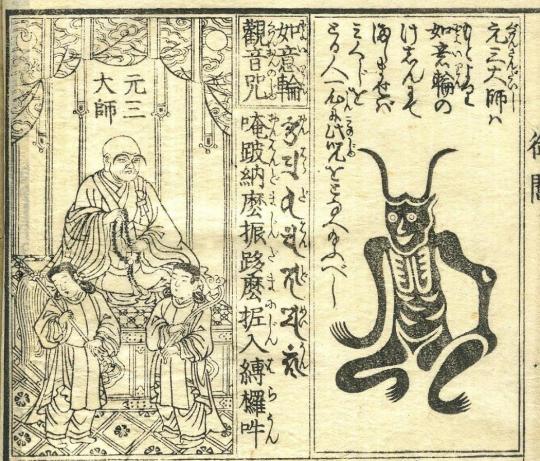

The supposed lesbian couple from Tengu Zōshi; image from Haruko Wakayabashi's The Seven Tengu Scrolls: Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

This sort of absence of evidence is a recurring pattern through history - you might recall my own attempts to find out what Bronze Age Mesopotamian sources have to say on this matter. Before the Meiji period, when the term dōseiai (同性愛) was coined as a calque of Charles Gilbert Chaddok’s freshly invented label “homosexual”, there wasn’t even a distinct Japanese term which could be applied to lesbian relationships. Once again, this does not indicate this phenomenon did not exist - but it does indicate that due to extreme levels of sexism in the perception of both sexuality and relationships it was difficult to even imagine for the average author. Faure suggests the prevailing attitude was presumably similar as in continental Buddhism, in which lesbian love “was at best perceived as a poor imitation of heterosexual relations—or a preparation for them—and as such condemned” at least in monastic rules. To put it bluntly, only penetrative sex was regarded as real.

And yet, in spite of this, I do not think it is wrong to wonder if perhaps what seems like subtext to a modern reader is actually intentional. This is obviously a reach, but given that relationships between women - not even romantic ones - were historically not a major concern of most authors, I would argue it is not impossible that a work which revolves virtually entirely around the relationships between female characters was written by a woman. Perhaps a woman romantically interested in other women, even.

Even more boldly, I’d ponder if perhaps the ambiguous gender of the fox before transformation was meant to make the romance palatable to general audiences. Note that while foxes transforming is a mainstay of both Japanese and Chinese literature, the change of gender is actually quite uncommon in such stories, making this single reference all the more unusual. Granted, gender change is hardly a major focus in the story of Tamamizu. The only real indication the fox is male is the decision to take a male human form at first, but beyond that, things get muddy to the point the matter of gender in the story evidently warranted an actual study, as I pointed out earlier. As you’ve noticed, this matter was approached in different ways by translators too.

I personally think the most important factor is the fact Tamamizu refers to herself with this name in the final poem. This name is intimately tied to the distinctly female identity she took. Whoever she was in the beginning, by the end of the story she is clearly Tamamizu. If one felt particularly bold a case perhaps even be made that Tamamizu can be read as a trans woman based on this, perhaps. I think simply disregarding the brief reference to a male form is valid too, though.

Even if these arguments were to be refuted fully, I would argue that there is a further reason why at the very least reinterpreting the story as dealing with a gay relationship is not against the spirit of the original work. As I outlined, the tale of Tamamizu seems to draw inspiration from a very specific genre of fox stories, in which foxes are essentially a metaphor for people seeking relationships which were frowned upon. Obviously, the fact that Tamamizu is not a human by default makes any relationship she would be involved in somewhat unusual and frowned upon, but that does not assign a different metaphorical meaning to her struggle.

Is Tamamizu even really fully a fox and not a human at all by the time she writes the confession of her love, though? The old fox seems to basically dispute if she still thinks like an animal. We also know that she maintained her human form for so long her biological relatives assumed she had passed away. She also found acceptance of virtually every single human character in the story - save for herself, that is. It’s also not like it’s hard to reinterpret her struggle specifically with the inability to consummate the relationship through the lens of the medieval Buddhist views of female sexuality, rather than through the lens of the general view that relationships between human and transformed foxes were doomed to failure.

To paraphrase Cynthia Eller’s evergreen quote about futile search for nonexistent matriarchal prehistory in ancient texts, I do not think an invented wlw past can give anyone a future, but at the same time I do not think it means we should conclude that nobody ever had similar experiences in the past, or that we can relate with works even in ways their authors did not intend. For this reason, I would ultimately argue in favor of embracing the Tale of Tamamizu as a narrative which can be read as a lesbian love story.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, The Red Thread. Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality (please note: read this book very cautiously since multiple content warnings apply. Faure is a remarkably progressive author, so it’s not about his personal attitude or anything. The problem is that it is not possible to deny much of the Japanese Buddhist discourse about homosexuality had little to do with modern notion of gay relationships, and essentially amounts to explaining when exploitation of children is a pious act)

Rania Huntington, Alien Kind. Foxes and Late Imperial Chinese Narrative (some sort of explicit content warning applies here too, though mostly because some of the discussed works are trashy Qing period erotica. More funny than anything.)

Xiaofei Kang, The Cult of the Fox: Power, Gender, and Popular Religion in Late Imperial and Modern China

Keller Kimbrough and Haruo Shirane (eds.), Monsters, Animals, and Other Worlds. A Collection of Short Medieval Japanese Tales

Jacqueline Stone, Medieval Tendai hongaku thought and the new Kamakura Buddhism: A reconsideration

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

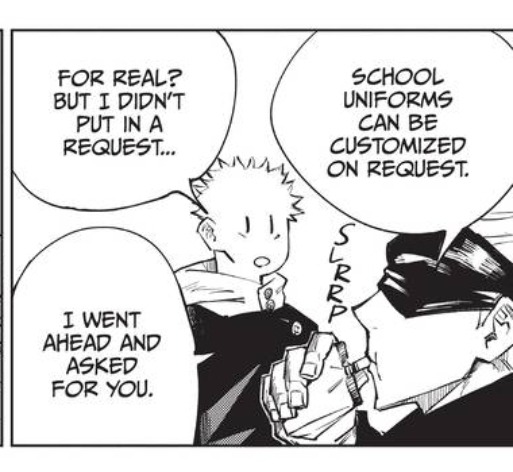

The Yagasuri Panel's Meaning + Gojohime and Sprituality

Hello, everybody! I know I've been gone for the past two years but I'm finally back. With the release of the latest chapter I've been incredibly devastated but it still won't stop me from being delusional! Since there has been a lot of talk surrounding Gojo and Buddha, I've been doing some research, and I think I found something that potentially draws us closer to the meaning of the famous Yagasuri panel :)

CHAPTER 236 SPOILERS AHEAD

As a quick refresher, the pattern displayed in the background of Gojo and Utahime is a traditional Japanese pattern called yagasuri. According to the sources I found on the internet, the arrows are related to archery, and thus were a common pattern on male clothing. The design represents the unwavering nature of an arrow because once it is shot, it will never return. Brides in the Edo period wore the pattern as a symbol of good luck, ensuring that they will not have to return to their families. Additionally, in Buddhism, the arrows embody the fight against evil.

There are a few interesting things I'd like to point out about the information above. For one, from all the pictures I've seen, the arrows in the yagasuri pattern are typically pointed downward, whereas in the cover, they are pointed from Gojo toward Utahime. Two, the pattern's relation to Buddhism and Buddha. Since there are many parallels to Gojo and Buddha, I went on a quest to research more about the story of Buddha (Prince Siddhartha) out of my own curiosity. What's fascinating is that supposedly in his early life, he won his wife, Princess Yasodhara, in an archery contest. They were married at an early age and had a newborn son when Prince Siddhartha was 29. Unfortunately, he leaves his family behind to embark on a journey toward enlightenment.

Aren't these details crazy?

Buddha's wife was a princess. Utahime means song princess/diva/songstress.

Both couples share a connection with archery/arrows.

Gojo is currently 29 years old in the manga and is theorized to reach enlightenment soon (assuming he truly is following the path of Buddha).

BUT THERE IS MORE.

Apparently, Yasodhara has been Buddha's wife for many lifetimes. While there are numerous stories of the two's history in their past lives, the one I'd like to bring attention to is from The Collective Sutra of the Buddha's Past Acts. The text recounts the first time Prince Siddhartha comes into contact with Yasodhara in a previous life as a Brahmin (Hindu priest) by the name of Sumedha, while she was a woman named Sumidha. As he waits for Buddha Dipankara to arrive to the city of Paduma, Sumedha decides to buy flowers as an offering. He then discovers that the king bought all the flowers as his own offering to the Buddha, much to his dismay. But in the corner of his eye, he spots a beautiful young girl with 7 lotuses in her hands and offers to buy one from her. The girl, Sumidha, vows to give 5 of her lotuses to him in exchange for being his wife in all of their next lives. In another version, Sumedha and Sumidha went to a city where Buddha Dipankara was expected to visit. He then asks her for one of her flowers to throw as an offering to the Buddha. She then asks him to throw another one in her behalf. Buddha Dipankara summons the two and reveals that they will remain connected for many lifetimes and help each other attain enlightenment.

In the latest chapter, we see a panel of lotuses. From what is visible, there are 7 flowers. 7 flowers? 7. Flowers. I also think it's a funny coincidence how Sumidha promises to give Sumedha 5 flowers due to the fact that we associate Gojo with the number 5 because of the kanji in his name.

Just like Prince Siddhartha and Princess Yasodhara, I believe Gojo and Utahime are connected by fate. In the manga, whenever Utahime appears, it is almost always in relation to Gojo. They are made to contrast each other in almost everything besides motivations. Their color palettes, the schools they teach at, their values, and positioning in the jujutsu hierarchy. These are not coincidences.

And yet, despite all these differences, there seems to be a mutual level of trust between the two of them that transcends their usual bickering dynamic. Utahime has no obligation to help Gojo, but she does anyway. She CHOOSES to help him because she understands they share a common goal: protecting and nurturing the students. On Gojo's side, he CHOOSES to request a helping hand from Utahime first. Out of all people, he wanted to reveal his suspicions to her first. While Utahime provides assistance when she can, Gojo looks out for her when he can.

He claims that it is a pain to look out for the weak, but he continues to protect her. Gojo and Utahime put their lives at risk helping each other because they TRUST each other.

If my theory is true and it turns out that they are connected by fate, it would explain the unusual direction of the yagasuri in chapter 34. No matter how many lifetimes have passed, the soul of Gojo will always return to Utahime, just like how Sumedha promised Sumidha that he will marry her in every life. And the soul of Utahime will remain assisting him toward the journey of enlightenment.

I'm not saying they're married or anything but their relationship honestly parallels Prince Siddhartha and Princess Yasodhara so well. Although both of their narratives appear to culminate in the man's quest for enlightenment, they nonetheless serve as compelling illustrations of the power of a relationship founded on mutual trust.

___________

I might add on to this post later on if I feel like I missed something, but let me know what you think! :D These reaches are my specialty so be sure to take it with a grain of salt and don't take it too seriously. It's all in great fun :3

254 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know this would be terribly inaccurate and morally wrong, but it's taking too much space up in my brain and I can't write NSFW to save my life and I'll stop rambling and get to the point about this random hoe ass dream I had the other night about Bear (Graves).

But that table in the middle of their storage area room thing (with the cages)? Imagine getting railed on that table. Horrible consequences if you're caught, but in the moment that doesn't matter.

I didn't even really clock the morally wrong portion of this until just now—I just immediately started writing it.

Warnings: MATURE | 18+ — pseudo exhibition kink, corruption (as in, MC does everything possible to break Bear), risk-seeking behaviour; light smut

Word Count: 2,2k

Notes: it's been so long since I wrote smut that I kinda forgot how. alsoooooooo. it's deffo early season 2 Bear. With the beard and the unhinged madness and tragic angst. Okay? Okay.

It's a whim.

One of those terrible ideas you sometimes get—like the insatiable curiosity to know what it would feel like to snuff out an open flame between your thumb and forefinger, or lick the anode and cathode of a 9V battery just for the thrill of it. The electric hum of recklessness that surges through your veins, pitched right between the accompanying high of a short-lived adrenaline rush. An addictive sense of danger that isn't really dangerous.

It isn't enough to kill you, or cause any severe injuries—no. You're not stupid. It's just one of those passing no good, bad, and very terrible ideas that leak from that place inside your head where madness and idiocy spool.

Sometimes, it doesn't even hurt.

(But you've always liked it better when it does.)

This, then, must be that.

This, of course, being:

Bear—so austere, so stalwart—bracing his thick fingers against the back of your neck, palm so wide it swallows you whole. Clipped nails pinching your skin when he digs in tight, holding on to you as he fucks you stupid, fucks you senseless against a metal table, perfectly perched in the middle of the room like an altar.

His nails cut a scratch on your hip when he pulls you back by the bone to meet his heavy, hurried thrusts, growling low in his throat at the madness of this all. The danger. The recklessness.

Eyes oscillating between the open doorway split into three possible entry points where anyone—Chase, Trevor, Buddha, Caulder—could walk in and see, catching Bear fucking you over a table; and you—

Bent over, fingers scratching at the linoleum beneath your hands, keening desperately for more.

It's more brutal than you'd expect him to be considering where you are, where he is, but there's a weight to the way he pounds into you, a palpable sense of urgency, and need. Rapacious, you think, and wonder if it's the tantalising aspect of exhibitionism, the fear of getting caught, that brims white-hot in the balmy air between you, or if it's the setting alone that threatens to undo him.

Fucking out in the open—with a man who yelped when you tried to ride him on the bed of his stupid pickup truck under the stars; vanilla incarnate, all American apple pie left to cool on an open windowsill in the heartland—is probably as close to true trouble as a man like him, the one bent over you now, has come before. You wonder if this is his Saddam. If he scents brimstone in the air when he curls over you, staining your skin with droplets of sweat that pools down from his brow, drips off his temples.

It was that same sweat that started it all.

Anger carved canyons into his forehead, ploughing five neat, little lines through tanned skin—flushed slightly pink near his hairline, and bleeding down across the bridge of his nose, the patch of skin between his lash line and beard, undoubtedly from standing on the sun-beaten shores of Virginia Beach all morning. The sweat that beaded across his skin was patchy, drying into patches of congealed salt above his brow, but dripping down his temples in rivulets of exertion, and cutting a clear path to his jaw, where it fell, pooling like a lagoon in the dips of his collarbones.

You wanted to lick it off.

An odd thought considering the arched reprimand he was in the middle of doling out. Sharp, slurred words of can't be here, and reckless, all undercut with an air of something balmy, something hot that simmers below the surface.

His eyes flashed, cool blue to cobalt, when you lifted your shoulder in a lazy, half-hearted shrug, shirt slipping down, exposing skin to his irritated gaze, and, oh. Oh.

The scorching heat you felt wafting off of him in puffs of humid air had little to do with temperature, with anger.

The words, then, took on a new meaning.

Can't be here, can't do this here. Reckless.

And so, you leaned up on the tips of your toes, and flicked your tongue across his skin, eyes lidded and heavy as the briny tang of sweat and seawater flooded your senses.

It was surprising that he let you. That after some more growling protests about shame, and public decency, he quieted fairly quickly when you slipped your hand into his trousers, letting the heft of him fill your palm.

An incorruptible man, corrupted.

Opposites attract, you think, and then bite the notion in half when he slides in as deep as he can go, husking out a muted fuck, fuck, fuck, feels so fuckin' good into your shoulder. Opposites, maybe. But something about the way he grabs you hard enough to leave marks on your bones, drags you back into his harsh ruts, his frantic pace, makes you think something reckless, something damning, lives inside him, too.

(He never would have let you tug his trousers down over his hips, let you arch over the table for him, if he didn't, after all.)

"This is—" his breath is humid on your skin, hands spasming over your flesh. You taste clarity in his words. Cognisance bleeds into them, spilling panic, and frenzied worry over your flesh. "This is stupid. We're gonna get caught—"

He huffs, and the rough scratch of his beard skates over your skin when he mouths against the curve of your bone.

There is a moment when you think he might pull away. Where the urge, the drive, to be proper and pious, prim and good, brim up through the overwhelming dizziness of cacoëthes that spindles through your marrow, but you arch into him until you're pressed taut to his hips, full and gasping from having big Bear inside of you this deep, and tuck it back into the box it snuck out of.

There's no place for decency when he has you bent over a table where anyone can wander past and see how good you take him.

So, you push back against him, taking him in as deep as you can, and then deeper still when his hips stutter at the sudden push. It edges into too much when he's pressed flush against the soft curve of your ass, but you swallow down the whimper, and rock back on your heels, swaying against him until all you see is hazy gunmetal swimming in front of your eyes.

It's always on that uneven edge of pain with Bear—dual sensations of too much intermixed with a heady thrum of pleasure that buffers out everything. A test of your mettle. He quizzes you on the limits of your resolve when he bucks his hips, sliding inside as deeply as he can go. Eking out a place within you that you might have been untouched, undiscovered, until him.

Where his tests are physical—pushing into you as deep as he can, until you swallow him whole—you excel in destruction. The erosion of propriety. His self-control.

(He shatters so prettily in your hands, like a supernova scattering across the inky black sky.)

This, then, is his test.

And he clues into it almost as quickly as the plan formed inside your head, spooling fast and recklessly in that place that convinces you that adrenaline is your friend, and that climbing higher is always the goal. The spot inside that makes you always pick dare instead of truth.

Bear knows—knew—of your plans when you pressed your lips to his, and still let you. A quick glance to the open doorway as you slide your tongue against his. The press of his fingers on the bow of your lips, a firm admonishment not to be too loud.

You could take it as:

Don't let us get caught.

And you do. But you also hear the unsaid words murmured into your ear when he fucked you harder, hips pistoning into you as if daring you to make a sound:

Don't let this end too soon.

"You're so bad, Bear," you coo, words tangled in pleasure as the blunt head of his cock batters into that spot behind your navel that never fails to make you sing. It rises. A quick flash of heat roiling in your belly; the whine of a coil being pulled too tight. Liquid bliss in red-hot agony. "Fucking me like this. I bet you want them to see. I bet you want them to watch you fuck me, don't you?"

The hiccup in your voice belies the accusations in your words. A tremulous, teasing warble that is met with his sharp, heady groan.

"Oh, f–fuck—"

He's close. You feel him swell. Hear the rumble in chest as he loses that mechanical rhythm; a stutter of his breath, his hips. The bones in your hip ache when he digs in tight, holding you still as he pounds you with a fury unmatched by anyone else you'd ever known. He takes you like he's working out a problem. Like he's on the opposite lines of an allegiance, and is trying to fuck you stupid enough to ramble out the answers to the questions he asks. It disintegrates into madness. Desperation. His measured thrusts grow sloppy. His breaths ragged.

The implosion of his self-control is almost more euphoric than the flood of molten pleasure blooming in your core. Your release offset by the unignorable crumbling of his resolve.

"Come for me, Bear," you pant, your breath whitening the gunmetal table with plumes of condensation. "Come for me—"

His hand presses against the smooth slope of your neck, pushing your cheek into the slick table. His thick fingers spasm as he grows frantic, desperately chasing his own end in your spasming body, ready to follow you—quick and reckless—over the edge of a precipice, filled with an adrenaline-rush spiking through the pleasure.

Things just feel better when it's dangerous, after all.

Bear comes with a groan he can bare smother, pulling your hips back into his as he spends himself inside of you, the punchy grunts of a well-earned victory tumbling from his lips. The sound bounces off the condensation-slick walls, renting the air in two. His heavy breaths are magnified in the sudden absence of silence that always seems to follow a loud sound.

His misery-filled groan is muffled by the back of your crown when he tips forward, and buries his face into your hair. In his defeat, you victory. A sweet damnation that you relish as he struggles to regain footing after losing control. His brassbound resolve is still in tatters, and spilled across the back of the table he'll use tomorrow with everyone else, haunted by the images of you spread out and willing as he tries to pretend he doesn't know what it feels like to grip the end of the table and fuck you senseless in a room designed to amplify all sound.

You grin into the metal when he husks out a mangled fuck into your sweat-slicked hair. It reeks of resignation. Of a man who stood so long on the crown of propriety slinking down to the depths of hedonism and bliss. Breaking the rules feels almost as good as fucking on top of them, and your mind races with all the ways you can break him again.

And Bear, as usual, has a tap into that place inside that leaks bad ideas, and can only shake his head with a huff.

He doesn't even bother saying no.

(Caulder owes you ten bucks. It seems you can teach an old, pious seal new tricks.)

Your legs are still shaking like a newborn fawn. You feel him inside you still, and the phantom stretch of him touching places and pieces of yourself he really shouldn't makes you quiver. The ache in your thighs is the good kind, though. The lasting impression of success after obtaining exactly what you set out to do.

Climbing a mountain. Running five miles. Fucking Bear Graves in the locker room with everyone else just a breath away.

(Check, check, and check—)

He helps you into the truck, eyes sweeping over your shoulder to look for anyone else in the parking lot who might ask questions. Solid, reasonable ones like why do you stink like sex? and did you just fuck them in the locker room, Bear?

You could try and reassure him that it's empty. That no one cares. That it's all in his head.

But you like the clench of his jaw, the flash of teeth when you giggle at him. Once the high of his release comes down, anger will follow. The kind that makes him loom. He'll lecture you about safety and decorum and not to sneak into his work to fuck him—

He'll wind himself up. Get himself nice and heated. He'll see it as a question to his authority. A tremor in his self-control.

And to regain the footing he lost—

Well.

It'll be a good night for you.

"You're a bad influence," he mumbles into your jaw, words muffled by his heavy breath he buckles you in.

You count each line in his forehead as a win, and try not to preen. "You love it."

#Joe Graves#Joe Graves x Reader#Bear Graves x Reader#i hate editing my stuff and tagging things#and that is all#Bear Graves#Bear x You

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

@alightingdove

I'm fully aware of the weirdness. I'm very aware of the world's religions and their differences. My point is that the virtues of Buddhism are, generally, well-intentioned and sustainable from a secular perspective. We know why the Buddha became an ascetic - he witnessed sickness, aging, and death, and he decided to leave his luxurious life in pursuit of meaning.

Had to break this discussion out of the comments section because I think you're making a number of serious errors in your assumptions.

One--Buddhism is not an especially noble or enlightened religion. As this Buddhist and scholar of Buddhism points out, traditional Buddhist morality is deeply medieval, and very out of step with modern values. It is patriarchal, puritanical, and authoritarian. See also this post and this one.

Two--we have narratives about the Buddha, composed centuries after his death. As scholars of religion like Stephen Shoemaker and the cognitive scientists they have based their work on have pointed out, oral traditions are very bad at preserving authentic historical detail. They very quickly become adapted to serve the politics of later eras, and later traditions get written back onto the founders of movements to justify themselves. This is certainly true of Christianity, which had developed elaborate ahistorical traditions about Jesus within a hundred years of his death; it is even more true of Buddhism, whose oldest texts date to something like four hundred years after the Buddha's death. Islam, Zoroastrianism, Taoism, and many other traditions centered on a single founder figure (even one who was certainly historical, like Muhammad) have similar problems.

Three--religions catch on for many reasons. "Disillusionment" seems to be only one factor out of many. People adopt new traditions because of politics, identity, millennarian fervor (very big in early Islam and Christianity), hope of strategic benefit (knowledge or power from the gods), because they're forced to under threat of violence, and so forth.

So I think it is a bad idea to ascribe particular generosity or wisdom to (or to be excessively deferential to) people who, even if the traditions surrounding them are entirely authentic, made claims about the world which are unprovable or outright false, and whose morality was repugnant. And it's especially a bad idea to do so just because they have proven historically successful, given that the reasons they have proven to be thus may be pretty arbitrary.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

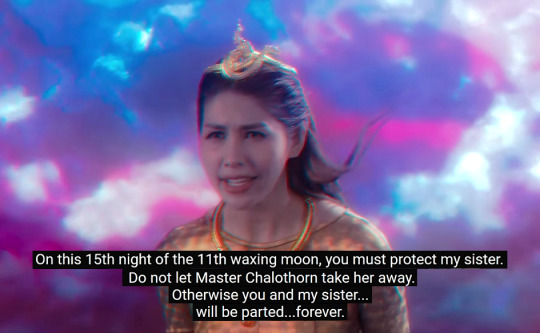

THE SIGN EPISODE 8 – WANWISA'S WARNING

We've been told before in The Sign that the 15th day of the 11th waxing moon is a date that is especially significant and powerful for the nagas.

The last day of the Buddhist Rains Retreat (also called Buddhist Lent by some), this date (Wan Ok Phansa) is mentioned by nagini Wansarut to Phaya's previous garuda incarnation at Ep.8 [3/4] 8.37 as the date when the Buddha returned to the human world "from the second heaven where Indra dwells", and the nagas and naginis breathed out fireballs in his honor.

And this is why the Naga Fireball Festival is also held around the time of Wan Ok Phansa.

Separately, at Ep.3 [3/4] 12.26 (when Tharn and Phaya explore the Dinphiang Cave) Sand's voiceover also recounts the legend of the naga princess who is compelled to return to her watery homeland underground on the date of Wan Ok Phansa (the 15th day of the 11th waxing moon, or the last day of Buddhist Lent), and loses her human lover in the process.

So Chalothorn must have been biding his time for this particularly auspicious date to come around, when he would finally be empowered to take back his betrothed nagini princess, and break the connection once and for all between garuda Phaya and naga Tharn/Wansarut (and is the gist of Wansarut's golden nagini sister Wanwisa's warning).

Chalothorn must have been attempting to kill Phaya from early on in order to prevent him from obstructing the greater scheme of reclaiming Wansarut/Tharn from the reincarnation cycle and reinstating his nagini's semi-divine status, away from the garuda.

But of course all attempts on Phaya's life by Chalothorn were futile, as he was under the protection of Tharn's nagini-soul amulet (that the Thai subtitles also call a naga gem, akin to Wansarut's heart) – the physical embodiment of Wansarut's dying vow to protect her beloved garuda throughout all future reincarnations:

Wansarut's vow here also reveals the supernatural impetus behind all the times Tharn saved Phaya's life earlier, e.g., during the Ep.1 mock-hostage rescue and open water challenge, the encounter with the masked Molotov knife-man in Ep.4, and the battle with the tattooed serial killer in Ep.5. 😢

It's consistently been the bigger, macho Phaya being saved by the smaller, slighter Tharn/Wansarut. And this is just one of the many ways that The Sign has been bucking expectations of a Thai BL series. 🤩 But come the next Wan Ok Phansa it will be time for Phaya to prove his worth in return, and battle to save his fated lover Tharn/Wansarut from the clutches of the possessive naga Chalothorn instead. 😔

#the sign#the sign the series#naga and garuda#phayatharn#the sign phaya#the sign tharn#the sign wansarut#the sign wanwisa

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

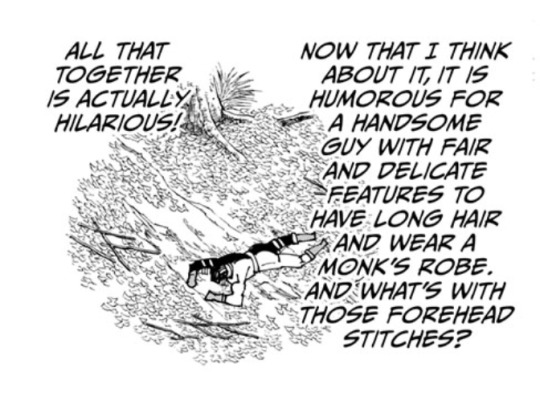

So can we get more context on this situation for the Tang River Water au?

referencing this au.

Literally one of the first things Peng does when they get released from the Scroll is to try and kill who he thinks is Tripitaka [Tang]. Peng presses on Tang so forcefully that the stone around him cracks. Tang doesn't be looking so great afterwards either.

Only reason Tang isn't passing through Diyu after this scene is Azure mentioning that he's just the monk's reincarnation (which 100% must have tickles Peng pink since they of all people know how embarassing it must have been for Buddha's teacher's pet to fail to break the cycle of rebirth). I have seen aus where Tang does die in this scene and his Golden Cicada powers have to come in clutch to keep his soul there. (link to a really cool animatic)

But in the "Mother Child River Tang" au?

Peng immediately takes one look at this *obviously* pregnant monk and just starts screeching with laughter! You know that sound peacock's make thats like a strangled laugh? That is all Peng is doing for their first five minutes out of the Scroll.

Yellow Tusk has already given Azure a warm welcoming hug and gotten caught up on the most recent millenium by the time Peng manages to catch their breath.

Peng: "The- [peacock cry]! The monk is- [more peacock cries!] ahhhhh! I can't even be mad at him right now! It's so funny!"

Tang, still a little hurt, now offended: "Rude. A pregnant man isn't that funny."

Peng: "But a pregnant monk is! Looks like that vow of chasity didn't stick eh?"

Azure: "Peng, they are not the monk."

Peng, laughter stops: "...then who the Diyu are they??"

Tang, emboldened: "I'm Tang! Reincarnation and/or decendant of the Great Monk! And this is my husband Pigsy, our son MK, and our friends."

Peng, tears in eyes: "HE MARRIED THE-!" [peacock cry!]

Azure & Yellow tusk: *both sigh tiredly*

On a more serious note, since Sandy was forced to push Tang out of the way of Yellow tusk's attack + Peng pinned him to the ground, the Monkey King's part of the Scroll is damaged, MK is having a mental breakdown, and if we combine this with "Slow Boiled Stone Egg" au - the Brotherhood has taken Yuebei Xing hostage? Tang is in a lot of physical and emotional distress rn.

Like... enough to trigger early labor-level of distress.

Bodhisattva Guanyin is summoned immediately to Subodhi's temple before any actual training can occur. She's (and many other buddhist deities) so preoccupied in making sure that the Golden Cicada and his baby survives that they are distracted from the threat sieging Heaven at that moment...

Pigsy has to be held back from trying to tear the Brotherhood apart himself. Zhu Bajie wasn't *just* "some demon". He used to be one of the most powerful Marshals in Heaven - commanding 80 thousand heavenly sailors/soldiers. In one mythology, Marshal Tianpeng was even a son of Doumu - the mother of constellations (making him the Queen Mother of the West's brother oddly enough).

Whos to say that Pigsy doesn't accidentally tap into the powers of that life? The whole naval power of Heaven is suddenly at Subodhi's school, waiting for the orders to turn the Brotherhood into a fine red smear on the wall. It's only Tang's own pleading that Pigsy doesn't act rashly.

The chaos does lead to an odd conciencidence occuring though...

Nezha, post-s4: "I do wonder... has the Jade Emperor broken the cycle of rebirth? If not, then that means the location of his soul could prove dangerous if left unchecked. I must contact the Underworld." *starts mediatating*

MK: "What do you mean?"

Nezha: "The Emperor was eons old. That amount of acculmilated divine power needs a host that can handle it. Like-"

Tang & Pigsy's baby: *snorts/burps loudly*

Nezha, realising: "-the child of the Golden Cicada and of the Doumu herself..."

Yama, King of Hell, astral projecting: "You guys are not gonna believe where the Emperor ended up! He's in a half-demon piglet somewhere- oh there she is!"

Tang & Pigsy: ( 0_0) (0_0 ) "uh oh"

#mother child river tang au#slow boiled stone egg au#lmk aus#pregnancy tw#lmk tang#lmk pigsy#lmk peng#lmk azure lion#freenoddles#freenoodlesshipping#lmk#lego monkie kid

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd say I'm becoming a nerd, but that ship sailed a long time ago. I guess I'm just expanding my nerdiness to other areas.

Anyway, MORE MYTHOLOGY!

So in Journey to the West, the Buddha explains that there are 4 'spiritual primates' that don't fit into any categories for immortals or types of creatures. Fans of Lego Monkie Kid are likely familiar with 2, the Stone Monkey Sun Wukong and the Six Eared Macaque. The other 2, the Long-armed Gibbon and the Red-Buttocked Baboon are a lot more obscure. They only get a brief mention in JttW because the focus of the chapter they appear in is Macaque, but the idea of a set of super powerful Immortal monkeys is just too fun to pass up, you know? So I've been thunking my thinker.

What if each primate was associated with a different realm (mortal, heavenly, lunar, and underworld) and element? I know the 4 elements (earth, water, wind, fire) are a western idea rooted in alchemy and eastern mythology has 5 elements (earth, water, fire, metal, wood), but there aren't 5 monkeys and this is just a thought experiment and not me trying to force western ideas onto eastern culture.

Got it? Good.

Now, Sun Wukong is very solidly earth because he's, you know, a rock. No surprise there. He was also born in the mortal realm and spent most of his life there, so we'll call him the celestial primate of the mortal realm while we're at it.

The Six-Eared Macaque is another easy one. A lot of LMK fannon associates him with wind, inferring that his heightened hearing has something to do with wind magic. He's also very closely tied to the moon because of the line in "Shadow Play" where he directly compares the Warrior (himself) to the moon. So Macaque is the celestial primate of wind and the Lunar realm.

Now here's where we get a bit more speculative and start using information creatively. There are 2 monkeys, realms, and elements left I want to use, so let's start with the monkeys so everyone has a baseline understanding.

The Long Armed Gibbon (Gibs, from now on) is described as being able to "seize the sun and moon, shorten a thousand mountains, distinguish auspicious from inauspicious, and manipulate planets and stars."

The Red Buttocked Baboon (Babs for short) has "knowledge of yin and yang, understands human affairs, is adept I'd daily life and can avoid death and lengthen its life."

Starting with the realms because they seem easiest to assign, I would give Gibs the Heavenly realm because of its ability to move around celestial objects like the sun, moon, planets, and stars. This leaves the Underworld to Babs, which I think fits nicely because their "knowledge of yin and yang" and "understand[ing] of human affairs" would make them a good assistant to the 10 Kings of the Underworld.

Next comes the 2 remaining elements, water and fire, which are a bit tricky because it could go both ways.

Gibs could be fire because the sun and stars are giant balls of burning plasma, but also water because the sky/heavens are often associated with an ocean or other bodies of water in several different mythologies. For example, in Egyptian mythology, Ra sailed his boat through the sky every day, while in early Abrahamic belief the sky was a huge dome with water on the other side, and rain happened when floodgates were opened to let the water through. In Chinese myth specifically, the Milky Way is often depicted as a river that is sailed through by various deities.

Babs could fit with fire as well because underworlds and hell-adjacent places are often shown to have fires to torment and punish the sinful dead, no surprise there. But there is surprisingly a lot of water symbolism in the realm of the dead as well. For example, some people may be familiar with the Japanese idea of the Sanzu River, very similar in concept to the Greek River Styx, as well as the Chinese Huang Quan/Yellow springs.

Personally I would pair Babs with fire because he has red in his name, making him the celestial primate of fire and the Underworld.

That leaves Gibs to be the celestial primate of water and the Heavenly realm.

I feel pretty good about this, but if anyone else has other ideas I'd love to hear them.

Sh*tpost Masterlist

#lego monkie kid#lmk#sun wukong#journey to the west#liu er mihou#six eared macaque#jttw#long armed gibbon#red buttocked baboon#crack theory#my theory#chinese religion#chinese mythology#4 elements#cool connection#no books this time we die like men#i've put more effort into this than i have most of my school or college research papers#maybe i should've been a mythology major...#shadowpeach#mythology sh*tposting#mythology#mythology and folklore#jttw inspo character ideas

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

For ROR, was wondering about any headcannon or drabbles you may have of Buddha, Shiva, and Hercules as dads??

Parenting headcanons

[ PLATONIC HEADCANONS ] [ Buddha, Shiva, Heracles ]

[ Records of Ragnarok / Shuumatsu no Valkyrie ]

Buddha's part is dedicated to the simp of the four sages, i miss u 🥺

Just a cute reminder that here you are the child 🐭

My conclusion is Buddha besto father ✨✨

Buddha

Buddha is a pretty chill man and that won't really change when he becomes a father, he isn't exactly estrict and he let his child do whatever they wants, still he can get protective over you (specially with the gods)

Buddha actually loves parenting, finding pretty cute almost everything you do, specially when you were a baby, just holding you gently close to him make his day way better, and he loves seeing you grow up too

That is why Buddha can get pretty clingy to you, wherever he goes you go with him and he is always carrying you, in his arms, in his back or in his shoulders, wherever you prefer

Since Buddha used to be a prince he has received a very good education, and he will teach you all knowledge he remember along side with all that he had learn in his own

He is a really supportive father for whatever you want to do, doesn't matter is an ambitious goal or something more simple you will always have his support

Even when he let you do whatever you want he makes sure you don't forget to be respectful, you have to respect other as well as others have to respect you, even him, he tell you more than once that if he ever feel that he is been disrespectful or invase with you don't hesitant on tell him

Is for sure that you will meet the other sages too, but Buddha doesn't fully trust them to take care of you (specially in your early life) just because he knows the mess they are he is the same, but will never stop you from hanging out with them and they loves having you around, so is a win win for everyone

Buddha says that he doesn't like to brag about whatever he did, but he actually do love it and a lot but just with you because he loves seeing you amazed and proud expression whenever he tell you how he become the man he is now. And that is a negative point with the sages, because while your papa tell you amaizing stories about him the sages tell you stories about the irresponsable mess he is whenever he is with them (specially Confucious and Jesus)

The moment you start having friends with people your age or just people you like he just motivate you to go with them not really interfering, even when he doesn't seem affected by it is just matter of time for him to start to feel lonely without you around all the time (and he tells that to the other sages just to be dramatic and mess with them)

Shiva

If someone ask him about his child he normally don't say much, he acts like isn't a big deal, it isn't not like he doesn't like his newborn because he does and a lot, is just that he doesn't show it to others but he is extremely happy for this and he tent to spend all his time with his child, specially when you were just a baby

Your naps are the perfect excuse for him to be lazy, he says that he just want to look after you while you sleep but he always end up sleep too, it got pretty common to find Shiva sleep with you on top of him (sleeping too)

He won't admit it out loud but he is weak to your cuteness, whenever you do something cute (that for him is almost everything you do) he melt, leading Shiva to spoil you a lot, if there is something you want you will have it, he just can't bring himself to say not to cute little you

He grows pretty clingy to you, always wanting to hold you in his arms and play with you, but as you grow up he start to give you more freedom, not like he has been possessive is just that he loves spending time with you

He loves braging about all the adventures he had in the past and all the fights he had to become the man he is now (he may or may not exaggerate or lengthen the story to make it more exciting because he loves to see your amazed expression)

He isn't exactly estrict so is more probably that Parvati, Kali and Durga will be the ones who look after your education more. Although you are free to choose the direction your life will take once you grow up

Shiva introduce you to everyone he knows, still he is a little protective over you so if he notice that you are comfortable or someone is bothering you (even if is his friend) he will stand up for you, no matter what age you are he always will stand up for you

Once you start getting your own friends and wanting to go out without your parents Shiva gets a little jealous but he won't stop you from doing it, you have to explore the world on your own and find what you want to do

Shiva is totally the type of father that will tell your friends embarrasing stories about you because he find them cute and to mess with you

Heracles

Heracles is a caring and pretty protective father, he is mixed between wanting to protect his child from everything and anything and wanting to let them explore the world on his own

When you were just a baby he was really nervious about carrying you, is just that you were so small and tiny that he is worried that he would hurt you, it takes him a while to get used to but he end up loving holding you close to him

Heracles isn't exactly clingy but he likes to spend a lot of time with his child, and he gives you more freedom as you grow, again because he wants for you to explore and learn all you want

Also he used to carry you around all the time as a baby but as you grow he stop doing it so much for you to walk around all you want, although he will never say no whenever you ask him to carry you, no matter what age you have

Heracles will introduce you to the gods and humans he know (mainly the ones that are of his fully trust, specially when you were just a toddler), although he won't force you to get along with them, he hopes you will but won't force you if you don't

Since he is a god he will be busy from time to time so he will have to leave you with someone capable of taking care of you (probably Hermes), and, of course, it has to be someone you like and are comfortable with

Speaking of, whenever he goes out to fullfil a work he always tries to bring something for you on his way back, a gift of something he knows you will like (no matter how old you are he keeps doing it), and he always tell you the story of his adventure (avoiding disgusting details)

He isn't someone who likes to brag, but he can't say not to you whenever you ask him about the stories of all his adventures. And if you see him or tell him that he is a hero he will be so flustered by it and it gives him a lot of motivation to continue with his work

He want for you to grow up as someone caring and strong, he tell you that you should respect everyone, gods and humans, just as they have should respect you too. He won't let you be revelious but he isn't aggresive when confronting you

If you want learn how to fight he will happy to teach you (but will go easy on you since the circumstances aren't forcing you to become stronge like were when he a young human), but then again if you aren't interested on it is fine, he wont force you

#shuumatsu no valkyrie#records of ragnarok#snv#ror#snv x reader#ror x reader#snv buddha#snv buddha x reader#ror buddha#ror buddha x reader#buddha x reader#snv shiva#snv shiva x reader#ror shiva#ror shiva x reader#shiva x reader#snv heracles#snv heracles x reader#ror heracles#ror heracles x reader#heracles x reader#anime and manga#anime x reader#anime x you#x reader#x gn reader#anime#manga

368 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on Kiara and the CCC Sakura's?

Kiara is a character that took time to warm up. I played CCC and loved Kiara and Anderson as a pair but didn't like either character individually. SE.RA.PH also impressed me very little, but she got a fun part to play in Paradise Lake so that's one contribution from FGO. But it was with her part in Tsukihime, literally just two lines of dialogue, that I got to think back and realize that I like Kiara, actually.

Anyways, the central idea that defines the whole of Kiara's character is that she doesn't know how to read. She's an unstoppable force that reshapes the world with her genius of religion, sexuality, psychology, programming, and magecraft, but literature is her weakest subject. She's blind to themes and symbolism, dull to metaphors, and unaware of subtext.

Her story is that she was born with the saintly nature of a bodhisattva, but confined to a bed in an isolationist Tachikawa cult. It was a harsh childhood where she was sick and objectified but she had the company of books telling her the teaching of the Buddha and heartwarming tales like The Little Mermaid.

Her life changed at age 14 when she was introduced to the internet. Thanks to it, she learned her disease was easily treatable and fixed herself, but most importantly, she discovered no one in her village healed despite it being super simple. Remember this is a Buddhist devotee who sucks at reading. She grew up reading that the sattva defines sentient beings as any life capable of compassion, and with her abysmal interpretation skills, believed this was completely literal. Therefore, the people around her weren't sentient. By Kiara's dumbass definition, was the only human being she knew.

What makes Kiara is the fact that her dehumanization of others and the power her talents give her over people's lives often lead to megalomania. People kill themselves en masse over her and her reaction is thinking that's hot, actually. People confront and checkmate her and her reaction is to kill herself before the hero who took so many innocent lives to reach can have the satisfaction of doing it. (Amazingly timely with the new SE.RA.PH chapter that came the day after I received this ask)

But despite her pride consistently getting the better of her, that pride is still derived from the fact she is sentient, therefore capable of compassion. She's a natural-born bodhisattva (mostly) always extending the hand of salvation to those beneath her. Just... the functionally illiterate Tachikawa Buddhist way, which involves making the entire world nut into moksha. But hey, at least her heart is in the right place. I can fix her. (Note: this does not mean you can fix her. I'm talking specifically about myself because, at least on paper, I'm a licensed Japanese literature teacher)

CCC is the story of her attempt to cheat the Holy Grail War in order to reach the Enlightenment necessary for this, and her partner there is Andersen, the author of her favorite childhood stories. Andersen's Noble Phantasm can reshape fate to ensure her plot goes as intended but under the condition it must be true to the themes of Andersen's stories. And understanding the themes just happens to be Kiara's greatest weakness.