#controlled digital lending

Text

When is a library not a library? When it’s online, apparently

"If you buy a physical book, you are allowed to sell or lend it because of a legal principle known as the “first sale doctrine,” which gives the owner of a (physical) object the right to dispose of that object in whatever way they wish, regardless of copyright. The Archive argued that the same principle should protect the sale or lending of a legally purchased digital copy, pointing out that all the copies of books it lent out had previously been acquired lawfully by libraries.'...

The Internet Archive’s lawyers also pointed to a Supreme Court decision, from the nineteen eighties, ruling that using a Sony Betamax video-cassette recorder to make a copy of a TV show was fair use. The Archive argued that its digital copies of print books similarly “improved the efficiency of delivering content to one entitled to receive the content” in a way that didn’t “unreasonably encroach on the commercial entitlements of the rights holder.” "

#fair use#first sale doctrine#your VCRs#your DVR#You're right to record a TV show to watch later#controlled digital lending#digital libraries#libraries#archiving#preservation#digital preservation#the internet archive#internet archive#copyright abuse

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Internet Archive, Misinformation & the Problem of Digital Lending

I am in the embarrassing situation of having reblogged a post with misinformation. Specifically, the "Save the Internet Archive" post featuring the below image and its associated link to a website called "Battle for Libraries".

The post claims that the recent lawsuit the IA faced threatened all IA projects, including the Wayback Machine, which is not true. The link to a petition to "show support for the Internet Archive, libraries’ digital rights, and an open internet with uncensored access to knowledge" only has one citation, which is the internet archive's own blog.

After looking for more context, I found that even articles published from sources I trusted didn't seem to adequately cover the complexity of what is going on. Here's what I think someone who loves libraries but is hazy about copyright law and the digital lending world should know to understand what happened and why it matters. I am from the U.S., so the information below is specifically referring to laws protecting American public libraries. I am not a librarian, author or copyright lawyer. This is a guide to make it easier to follow the arguments of people more directly invested in this lawsuit, and the potential additional lawsuits to come.

Table of Contents:

First-Sale Doctrine & the Economics of E-books

Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

The “National Emergency Library” & Hachette v. Internet Archive

Authors, Publishers & You

-- Authors: Ideology v. Practicality

-- Publishers: What Authors Are Paid

-- You: When Is Piracy Ethical?

First-Sale Doctrine & the Economics of E-Books

Libraries are digitizing. This is undisputed. As of 2019, 98% of public libraries provided Wi-Fi, 90% provided basic digital literacy programs, and most importantly for this conversation, 94% provided access to e-books and other digital materials. The problem is that for decades, the American public library system has operated on a bit of common law exhaustion applied to copyright known as first-sale doctrine, which states:

"An individual who knowingly purchases a copy of a copyrighted work from the copyright holder receives the right to sell, display or otherwise dispose of that particular copy, notwithstanding the interests of the copyright owner."

With digital media, however, because there isn't a physical sale happening, first sale doctrine doesn't apply. This wasn't a huge problem back in the early 2010s when most libraries were starting to go digital because the price of a perpetual e-book license was only $14 -- about the price of single physical book. Starting in 2018, however, publishers started limiting how long a single e-book license would last. From Pew Charitable Trusts:

"Today, it is common for e-book licenses from major publishers to expire after two years or 26 borrows, and to cost between $60 and $80 per license, according to Michele Kimpton, the global senior director of the nonprofit library group LYRASIS... While consumers paid $12.99 for a digital version, the same book cost libraries roughly $52 for two years, and almost $520 for 20 years."

Publishers argue that because it's so easy to borrow a digital copy of a book from the library, offering libraries e-book licenses at the same price as individual consumers undermines an author's right to license and profit from the exclusive rights to their works. And they're not entirely wrong about e-book lending affecting e-book sales -- since 2014, e-book sales have decreased while digital library lending has only gone up. The problem, they say, is that e-book lending is simply too easy. Whereas before, e-book sales were competing with the less-convenient option of going to the library and checking out a physical copy, there is essentially no difference for the reader between buying or lending an e-book outside of its cost.

Which brings us to the librarians, authors and lawmakers of today, trying to find any solution they can to make digital media accessible, affordable and still profitable enough to make a livable income for the writers who create the books we read.

Further Reading:

1854. Copyright Infringement -- First Sale Doctrine

The surprising economics of digital lending

Librarians and Lawmakers Push for Greater Access to E-Books

Publishing and Library E-Lending: An Analysis of the Decade Before Covid-19

Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

Controlled digital lending is a legal theory at the heart of the Internet Archive lawsuit that has been proposed as one solution to the economic issue with digital media lending. This quick fix is especially appealing to nonprofits like the IA that are not government, tax-funded programs. Where many other solutions, like a legally enforced max price on e-book licensure for public libraries, would not apply to the IA, CDL would essentially be manipulating copyright law itself as a way to avoid e-book licensure altogether and would apply to the IA as well as public libraries.

Essentially, proponents of CDL argue that through a combination of first-sale and fair use doctrine, it can be legal for libraries to digitize the physical copies of books they have legally paid for and loan those digital copies to one person at a time as if they were loaning the original physical copy.

It is worth noting that the first-sale doctrine protecting physical media lending at public libraries does not cover reproductions:

“The right to distribute ends, however, once the owner has sold that particular copy. See 17 U.S.C. § 109(a) & (c). Since the first sale doctrine never protects a defendant who makes unauthorized reproductions of a copyrighted work, the first sale doctrine cannot be a successful defense in cases that allege infringing reproduction.”

This is where fair use comes in, which allows some flexibility in copyright law for nonprofit educational and noncommercial uses. Because the IA and other online collections are nonprofit organizations, proponents of CDL argue that they are covered by fair use so long as their use of CDL follows very specific rules, such as:

A library must own a legal copy of the physical book, by purchase or gift.

The library must maintain an “owned to loaned” ratio, simultaneously lending no more copies than it legally owns.

The library must use technical measures to ensure that the digital file cannot be copied or redistributed.

While this model first earned its name in 2018, it has been practiced by a number of digital collections like The Internet Archive’s Open Library since as early as 2010. It is important to know that controlled digital lending has never been proven officially legal in court. It is a theoretical legal practice that has passed by mostly unchallenged until the Internet Archive lawsuit. This is partially due to the fact that before releasing their official CDL statement in 2018, the IA had been honoring Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown requests of books in CDL circulation, which authors claim they are not always responding to or honoring anymore. The legality of CDL essentially depends on a judge's interpretation of current copyright law and whether they see the practice as an infringement, which would set a precedent for similar cases moving forward.

There are, however, U.S. court decisions that have rejected similar cases, like Capitol Records v. ReDigi, which argues that digital files (in this case, music files) cannot be resold without copyright holder’s permission on the grounds that digital files do not deteriorate in the same way that physical media does, implying that first sale doctrine doesn’t apply to digital media.

In 2019, the Authors Guild, a group of American authors who advocate for the rights of writers to earn a living wage and practice free speech, pointed out this court case in an article condemning CDL practices. They also argued that not only does CDL undermine e-book licensure (and therefore author profits off e-book sales), but it also would effectively shut down the e-book market for older books (the market for copyrighted books that were published before e-books became popular and are only being digitized and sold now). The National Writers Union has also released an “Appeal from the victims of Controlled Digital Lending (CDL),” that cites many of the same complaints.

Further Reading:

U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index

Position Statement on Controlled Digital Lending by Libraries

FAQ on Controlled Digital Lending [Released by NYU Law’s Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy]

Controlled Digital Lending Is Neither Controlled nor Legal

Appeal from the victims of Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

FAQ on Controlled Digital Lending [Released by the National Writers Union]

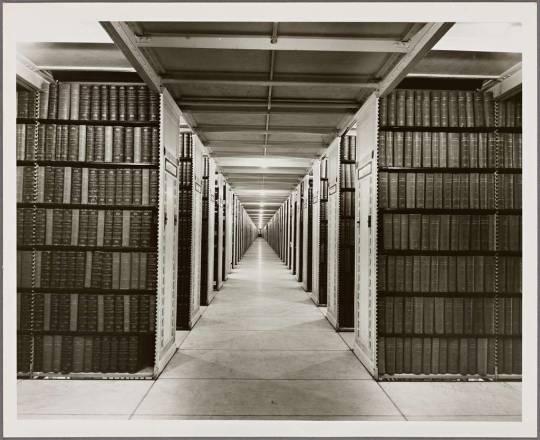

The "National Emergency Library" & Hachette v. Internet Archive

While the Internet Archive is known as the creator and host of the Wayback Machine and many other internet and digital media preservation projects, the IA collection in question in Hachette v. Internet Archive is their Open Library. The Open Library has been digitizing books since as early as 2005, and in early 2011, began to include and distribute copyrighted books through Controlled Digital Lending (CDL). In total, the IA includes 3.6 million copyrighted books and continues to scan over 4,000 books a day.

During the early days of the pandemic, from March 24, 2020, to June 16, 2020, specifically, the Internet Archive offered their National Emergency Library, which did away with the waitlist limitations on their pre-existing Open Library. Instead of following the strict rules laid out in the Position Statement on Controlled Digital Lending, which mandates an equal “owned to loaned” ratio, the IA allowed multiple readers to access the same digitized book at once. This, they said, was a direct emergency response to the worldwide pandemic that cut off people’s access to physical libraries.

In response, on June 1, 2020, Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House filed a lawsuit against the IA over copyright infringement. Out of their collective 33,000 copyrighted titles available on Open Library, the publishers’ lawsuit focused on 127 books specifically (known in the legal documentation as the “Works in Suit”). After two years of argument, on March 24, 2023, Judge John George Koeltl ruled in favor of the publishers.

The IA’s fair use defense was found to be insufficient as the scanning and distribution of books was not found to be transformative in any way, as opposed to other copyright lawsuits that ruled in favor of digitizing books for “utility-expanding” purposes, such as Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust. Furthermore, it was found that even prior to the National Emergency Library, the Open Library frequently failed to maintain the “owned to loaned” ratio by not sufficiently monitoring the circulation of books it borrows from partner libraries. Finally, despite being a nonprofit organization overall, the IA was found to profit off of the distribution of the copyrighted books, specifically through a Better World Books link that shares part of every sale made through that specific link with the IA.

It worth noting that this ruling specifies that “even full enforcement of a one-to-one owned-to-loaned ratio, however, would not excuse IA’s reproduction of the Works in Suit.” This may set precedent for future copyright cases that attempt to claim copyright exemption through the practice of controlled digital lending. It is unclear whether this ruling is limited to the National Emergency Library specifically, or if it will affect the Open Library and other collections that practice CDL moving forward.

Further Reading:

Full History of Hachette Book Group, Inc. v. Internet Archive [Released by the Free Law Project]

Hachette v. Internet Archive ruling

Internet Archive Loses Lawsuit Over E-Book Copyright Infringement

The Fight Continues [Released by The Internet Archive]

Authors Guild Celebrates Resounding Win in Internet Archive Infringement Lawsuit [Released by The Authors Guild]

Relevant Court Cases:

Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google, Inc.

Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust

Capitol Records v. ReDigi

Authors, Publishers & You

This is where I’m going to be a little more subjective, because each person’s interpretation of events as I have seen has depended largely on their characterization and experience with the parties involved. Regardless of my own ideology regarding accessibility of information, the court ruling seems to be completely in line with current copyright law and precedent. Ironically, it seems that if the Internet Archive had not abandoned the strict rules regarding controlled digital lending for the National Emergency Library, and if they had been more diligent with upholding those rules with partner library loans prior to the NEL, they may have had a better case for controlled digital lending in the future. As is, I agree with other commentators that say any appeal the IA makes after this point is more likely to damage future digital lending practices than it is to save the IA’s current collection of copyrighted works in the Open Library. Most importantly, it seems disingenuous, and even dangerously inaccurate, to say that this ruling hurts authors, as the IA claimed in their response.

The IA argues that because of the current digital lending and sales landscape, the only way authors can make their books accessible digitally is through unfair licensing models, and that online collections like the IA’s Open Library offer authors freedom to have their books read. But this argument doesn’t acknowledge that many authors haven’t consented to having their works shared in this way, and some have even asked directly for their work to be removed, without that request being honored.

The problem is that both sides of this argument about the IA lawsuit claim to speak for authors as a group when the truth isn’t that simple.

Authors: Ideology v. Practicality

Those approaching the case from an ideological point of view, including many of the authors who signed Fight for the Future’s Open Letter Defending Libraries’ Rights in a Digital Age, tend to either have a history of sharing their works freely prior to the lawsuit (ex: Hanif Abdurraqib, who had published a free audio version of his book Go Ahead in The Rain on Spotify before Spotify began charging for audiobooks separately from their music subscriptions) or have alternative incomes related to their writing that don’t stem directly from book sales (ex: Neil Gaiman, who famously works with multiple mediums and adaptations of his writing).

In these cases, the IA lawsuit is framed as an ideological battle over the IA’s intention when releasing the National Emergency Library.

Many other authors, including a large number of smaller names and writers early in their careers, take a much more practical approach to the lawsuit, focused on defending their ability to monetarily profit off their works. This is by no means a reflection of their own ideology surrounding who has the right to information and whether libraries are worth protecting. Instead, it is a response to the fact that these authors love writing, and they simply would not be able to afford to continue writing in a world where they do not have the power to stop digital collections from distributing their copyrighted work without their consent. These include the authors, illustrators and book makes working with the Author’s Guild to submit their amicus brief in Hachette v. Internet Archive.

These authors claim that controlled digital lending practices cause significant harm to their incomes in the following ways:

CDL undermines e-book licensing and sales markets, as most consumers would choose a free e-book over paying for their own copy.

CDL devalues copyright, meaning authors have less bargaining power in future contract negotiations.

CDL undermines authors ability to republish, whether as a reprint or e-book, out of print books once their publisher has ceased production. This includes self-publishing after the rights to their work have been returned to them.

CDL removes the income from public lending rights (PLR) that authors receive from libraries outside of the U.S. which operate on different lending and copyright standards.

The amicus brief provides first-person anecdotes from authors, including Bruce Coville of The Unicorn Chronicles, about how the rights to backlisted books, or books without an immediately obvious market, make up a huge portion of their annual salary. Jacqueline Diamond cites reissues of out-of-print novels as what kept her afloat during her breast cancer treatment.

It is worth noting that according to the Author’s Guild, some authors who originally signed Fight for the Future’s open letter defending the Internet Archive have even retracted their support after learning more about the specific lawsuit, including Daniel Handler, who writes under the pseudonym Lemony Snicket. The confusion stems from the use of the term “library” by both the Internet Archive and Fight for the Future. While authors overwhelmingly support public libraries, online collections like the Internet Archive don’t always fit the same role or abide by the same regulations as tax-funded public libraries. Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street, has written the following:

“To this day, I am angry that Internet Archive tells the world that it is a library and that, by bootlegging my books, it is simply doing what libraries have always done. Real libraries do not do what Internet Archive does. The libraries that raised me paid for their books, they never stole them.”

Further Reading:

Amicus Brief [Submitted by the Author’s Guild]

Fight for the Future’s Open Letter Defending Libraries’ Rights in a Digital Age

Joint Statement in Response to Fight for the Future’s Letter Falsely Claiming that the Lawsuit Against Internet Archive’s Open Library Harms Public Libraries [Published by the Author’s Guild]

Copyright: American Publishers File for Summary Judgment Against the Internet Archive

Publishers: What Authors Are Paid

Some of the commentators I’ve seen are disgruntled specifically with the publishers suing the Internet Archive, and I will say that many of these complaints are valid. The four publishing companies behind the lawsuits (Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins Publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House) are not known for the stellar treatment of their authors and employees. With the HarperCollins Publishers strike ending only a month before the IA lawsuit ruling, many readers are poised to support any entity at odds with one or more of the “Big Five” publishers. In this particular case, however, the power wielded by these publishing companies was used in defense of author’s rights to their works, for which The Authors Guild and other similar creator groups have expressed gratitude.

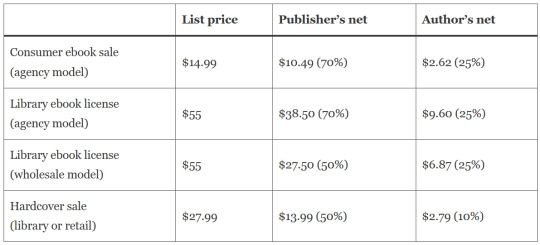

When it comes to finding solutions to the digital lending problem in general, it is important to understand what and how authors are paid for digital copies of their work. Jane Friedman has created the graphic below displaying the industry standards for the Big Five publishers. You can read more about agency and wholesome models here.

As you can see, authors and publishers alike benefit from e-book library licensure when compared to individual e-book sales, especially when you consider the time limits on library licensures. But advocates of this licensure model argue that the high prices for e-book licensure are designed to make up for the lost sales in e-books. While library goers buy more books than book buyers who don’t visit the library, the copies they buy typically vary by format. For example, a reader may borrow an audiobook from the library, decide they like it, and purchase a physical copy for their collection. While readers may buy a physical copy of a book after reading a physical library copy, they are unlikely to buy a digital copy after readying a digital library copy, making e-book lending a replacement for e-book buying in ways that physical lending doesn’t fully replace physical book purchases.

What ISN’T accounted for in this graphic is self-publication and what is known as a right of reversion. Depending on the wording of their contract, an author can request their publication rights be returned to them if the work in question is out of print and no longer being published. The publisher can then either return the work to “in print” status or return the rights to the author, who can then self-publish the work. In these cases, the 5-15% profit they would have made off their traditionally published book becomes a 35-70% profit as a self-published book. This is why authors are particularly frustrated with the IA’s argument that it is perfectly legal and ethical to release digital copies of books that are no longer in print. Those out-of-print works are where many authors earn their most reliable, long-term income, and they provide the largest opportunity for the authors to take control of their own works again and make fairer wages through self-publication.

The most obvious answer to this is that if authors are being the ones hit hardest by library and digital lending, then it is the publishers that need to treat their authors with better contracts. The fact that some authors are only earning 5% of profits on hardcover copies of their books (whether those are being sold to libraries or individuals) is eye opening. Alas, like the “we shouldn’t have to tip waiters” argument, this is much easier said than done.

Further Reading:

What Is the Agency Model for E-books? Your Burning Questions Answered

What Do Authors Earn from Digital Lending at Libraries?

You: When Is Piracy Ethical?

There are number of contributing factors to Tumblr’s enthusiasm for pirating. We are heavily invested in the media we consume, and it is easy to interpret (sometimes accurately) copyright as a weapon used by publishers and distant descendants of long-dead authors to restrict creativity and representation in adaptations of beloved texts. There are also legitimate barriers that keep us from legally obtaining media, whether that is the physical or digital inaccessibility of our local libraries and library websites, financial concerns, or censorship on an institutional or familial level. In fact, studies have found that 41% of book pirates also buy books, implying that a lot of illegal piracy is an attempt at format shifting (ripping CDs onto your computer to access them as MP3 files, for example, or downloading a digital copy of a book you already own in order to use the search feature).

The interesting thing is that copyright law in the U.S. has a specific loophole to allow for legal format shifting for accessibility purposes. This is due to the Chafee Amendment (17 U.S.C. § 121), passed in 1996, which focused on making published print material more available to people with disabilities that interfere with their ability to read print books, such as blindness, severe dyslexia and any physical disability that makes holding and manipulating a print book prohibitively difficult. In practice, this means nonprofits and government agencies in the U.S. are allowed to create and distribute braille, audio and digital versions of copyrighted books to eligible people without waiting for permission from the copyright holder. While this originally only applied to “nondramatic literary works,” updates to the regulations have been made as recently as 2021 to include printed work of any genre and to expand the ways “print-disabled” readers can be certified. Programs like Bookshare, Learning Ally, and the National Library Service for the Blind and Print-Disabled no longer require certification from a medical doctor to create an account. The Internet Archive also uses the Chafee Amendment to break their Controlled Digital Lending regulations for users with print disabilities. While applications of the Chafee Amendment are still heavily regulated, it is worth noting that even U.S. copyright law acknowledges the ways copyright contributes to making information inaccessible to a large amount of people.

Accessibility is not the only argument when discussing the morality of pirating. For some people, appreciation for piracy and shadow libraries comes from a background in archival work and an awareness how much of our historical archives today wouldn’t exist without pirated copies of media being made decades or even a century ago. But we have to be more careful about the way we talk about piracy. Though piracy is often talked about as a victimless crime, this is not always the case, and each one of us has a responsibility to critically think about our place in the media market and determine our own standards for when piracy is ethical. In some cases, such as the recent conversation surrounding the Harry Potter game, some people may even decide that pirating is a more ethical alternative to purchasing. Here are a few questions to consider when deciding whether or not to pirate a piece of media:

Have you exhausted all other avenues for legally purchasing, renting or borrowing a copy of this media?

Is the alternative to pirating this media purchasing it or not reading/referencing it at all? If the former, how are you justifying the piracy?

Who is the victim of this particular piracy? Whether or not you think the creator(s) deserve to have their work pirated, you need to acknowledge there is someone who would otherwise be paid for their work.

If every consumer pirated this media, what would the consequences be? Would you be willing to claim responsibility for that outcome?

If you got this far, thank you so much for reading! It is genuine work to try and understand the complexity behind every day decisions, especially when the topic at hand is as complicated as the modern digital lending crisis. Doing this research has changed the way that I understand and interact with digital media, and I hope you have found it informational as well.

Further Reading:

Panorama Project Releases Immersive Media & Books 2020 Research Report by Noorda and Berens

The Chafee Amendment: Improving Access To Information

National Center on Accessible Educational Materials

National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled

Books For People With Print Disabilites: The Internet Archive

Bookshare

Learning Ally

#Internet archive#IA lawsuit#digital lending#libraries#digital libraries#open library#controlled digital lending#national emergency library

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those of you who use the Internet Archive, you may have heard that something terrible happened yesterday. A lower court ruling said that they couldn't keep scanning and loaning books! Although they plan to appeal the ruling, and while their current stock appears to be safe for now, I think we need to find a way to make sure we can still read those books (many of which are rare or out-of-print) in a place where the law won't be able to find us, at least for a while. I know how risky this would be, but unless and until the Internet Archive prevails, I don't want to lose those books. However, in order to do this, I'm going to need a lot of help, since I don't really know how to do this sort of thing. Are you with me.

#internet archive#digital libraries#controlled digital lending#piracy#book piracy#share this on twitter#i do realize how extreme this sounds#but i won't lose access to those books

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

When is a library not a library? When it’s online, apparently.

by Mathew Ingram

In March 2020, the Internet Archive, a nonprofit created by the entrepreneur Brewster Kahle, launched a new feature called the National Emergency Library. Restrictions linked to the spread of COVID-19 had made it difficult or impossible for people to buy books or visit libraries in person, and so the Archive removed limits on the digital borrowing of the books in its database—of which there were more than three million, most of them in turn borrowed from physical libraries and scanned—and made them all publicly available, for free. The project was supported by a number of universities, researchers, and librarians. But some of the authors and publishers who owned the copyright to these books saw it not as a public service, but as theft. In June 2020, four publishers—Hachette, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House—filed a lawsuit. The Internet Archive shut down the project, and went back to its previous policy of “Controlled Digital Lending,” which only allowed one person to borrow a free digital copy of a book at any given time. But this didn’t stop the lawsuit—because the publishers argued that any digital lending by the Archive constituted copyright infringement.

Last week, Judge John G. Koeltl, of the Southern District of New York, finally ruled in the case. He came down in favor of the publishers and dismissed every aspect of the Archive’s defense, including the claim that its lending program is protected by “fair use” exemptions in copyright law. Koeltl wrote that the concept of fair use protects transformative versions of copyrighted works—a copy of a famous photo used in an artistic collage, for example—and that the Archive’s copies of books don’t qualify; the Archive made the case that its digital lending program is transformative because the practice “facilitates new and expanding interactions between library books and the web,” the judge noted, but he ruled that “making an invaluable contribution to the progress of science and cultivation of the arts” did not constitute transformation. In 2014, a court ruled that a book-scanning project led by Google was protected by the concept of fair use, but Koeltl pointed out, in his recent decision, that Google used the scans to create a searchable database, thereby increasing the utility of the books, rather than distributing complete digital copies. Any “alleged benefits” from the Archive’s lending, Koeltl wrote, “cannot outweigh the market harm to the publishers.”

READ MORE

#libraries#librarians#fair use#digital publishing#ebooks#book publishers#copyright law#controlled digital lending

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the article:

When it comes to physical books, copyright laws are relatively straightforward. Libraries purchase a book and lend it to patrons one at a time. But with digital copies, libraries usually rent e-books from publishers, lending them out a few dozen times before they have to renew licenses which can cost upwards of four to five times the amount of buying the book.

But the IA and other libraries have tried a different tack by buying and scanning copies of books to lend out to patrons one at a time through a model called Controlled Digital Lending (CDL).

What has become clear during this lawsuit, according to IA policy counsel Peter Routhier, is that publishers want CDL as a whole declared illegal. Moreso, Routhier writes that the lawsuit shows “publishers will continue to sue libraries over digital practices that were long considered fair uses in the physical world — even if they are done on a nonprofit basis with no measurable economic harm.”

In the current case, publishers argue that digital lending harms markets they claim to own and that CDL is not a fair use under copyright law. But library advocates argue that behind their argument of copyright infringement, publishers are simply trying to increase their profits while wresting control of the use of digital books away from libraries.

As Kyle K. Courtney, chair of Library Futures, argues, CDL is “not some form of library-sanctioned piracy,” but expressly based in copyright law, no different than lending a print book, while also offering the benefit of “broadening access to the books that library systems spend billions of dollars to collect and maintain for the public,” including out-of-print books that lack e-book licenses.

While libraries have tried to keep up with the growing demand for digital books, turning to a number of lending platforms like Libby and OverDrive, the high price of e-books can be a strain for any library, and even the most well-funded systems are struggling to keep up with demand.

That’s why many librarians believe lending digital books should be treated in the same way as physical books, and support for that belief has only grown since the lawsuit began, including from authors who originally opposed the NEL.

In an open letter, more than 300 authors organized by the digital rights advocacy group Fight for the Future said that publishers are “undermining the traditional rights of libraries to own and preserve books, intimidating libraries with lawsuits, and smearing librarians.”

Besides growing their e-book market and forcing libraries to pay heavy licensing fees, there is also a fear that publishers could gain more power in restricting access to information as they see fit, with libraries ultimately becoming “beholden to the whims of third parties, who might decide not to carry books on queer rights, abortion or other sensitive political issues,” and books being chosen by corporations as opposed to communities.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I did a little reading about the lawsuit issue, and I decided to donate to the cause, because 1) EFF is backing IA, and 2)

"Additionally, Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle told Vox in 2020 that “when nonprofit libraries have been sued in the past for helping their patrons access their collections, courts have ruled that they were engaging in fair use, as in the HathiTrust case.” A similar ruling was issued for a lawsuit against Google Books. "

and 3)

"For copyrighted books, Internet Archive owns the physical books that they created the digital copies from and limits their circulation by allowing only one person to borrow a title at a time. "

That was good enough for me, for this debate.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

A copyright win in the Internet Archive lawsuit

Maybe it wouldn't have been the death knell for authors, but a loss in this case would have had a serious impact on them. Sometimes news from the courts is good!

In a previous blog post, I wrote about a lawsuit that book publishers Hachette Book Group et al. has filed against Internet Archive (“IA”) et al. The lawsuit alleges that IA scans copyright-protected printed books into a digital format, uploads them to its servers, and distributes these digital copies to members of the public via a website – all without a license and without paying the authors…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

This is the second piece in The Atlantic recently about controlled digital lending (CDL). On its face it sounds like a battle between greedy publishers and libraries though I know it’s more nuanced than that.

Just like the writer, I get that publishers have to made a profit so they can pay authors so books get written and distributed at all. But the license or renewal fees charged by publishers for libraries with a CDL program seems like greedy profiteering to me. There has to be a middle ground somewhere and I get the sense that libraries would be willing to try to find one. I don’t think a publishing industry that just suffered a worker strike that also just had a consolidation deal struck down by the DoJ feels the same way.

I’m tempted to ask the two authors I follow, Neil Gaiman and Seanan McGuire, what they think but I know how full their ask boxes already are.

0 notes

Text

#libraries are wonderful#academic libraries#public libraries#support libraries#librariesmatter#digital books#ebook#ebook reader#research#accessible#controlled digital lending#open library#internet archive

0 notes

Text

Hachette v. Internet Archive

Hachette v. Internet Archive

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), with co-counsel Durie Tangri, is defending the Internet Archive against a lawsuit that threatens its Controlled Digital Lending (CDL) program.

The Internet Archive is a nonprofit digital library, preserving and providing access to cultural artifacts of all kinds in electronic form. CDL allows people to check out digital copies of books for two weeks or…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Motion for Summary Judgement by the lawyers for the Internet Archive, in their lawsuit with publishers over whether libraries are allowed to exist in the digital age without the permission of publishers, is quite readable, and I encourage everyone to read it.

The lawsuit is about two different, related issues -- Controlled Digital Lending (CDL) and the National Emergency Library (NEL).

The central and most important part of the case is about CDL -- which is a widely used technique for libraries to lend copies of books they have physical ownership of thru digital means. It's been used, without legal complaint, by numerous libraries, for many years -- but in this lawsuit, the publishers are trying to claim it should be illegal. It's critical to civil society (including authors and publishers) that CDL be confirmed as legal, as it provides a critical safety value against the dangers of limiting the distribution of cultural materials to single sources. If, for a given book, one person (or company) is allowed to control every time anyone reads it, that makes it dangerously easy for them (even with the best of intentions) to mislead society about what it says and doesn't say, or to succumb to pressure to make the work vanish. Such powers are noxious to a free, just and truth-seeking society.

The excuse (as opposed to the motive) for the lawsuit is the NEL -- a technical workaround for insufficient coordination among libraries worldwide at the beginning of the 2019 Covid pandemic. The Internet Archive provides technical assistance to many libraries in implementing CDL for the book copies they physically own; when nearly all libraries worldwide had to suddenly stop physical lending due to the pandemic, the many libraries who hadn't already implemented CDL (either independently or with the help of the Internet Archive) were left with physical copies they had the legal right to lend, but no practical way to do so. As a technical workaround for this, the Internet Archive estimated that the number of suddenly un-physically-lendable copies of the books already in their collection was so much higher than the number of lends that their servers could support that it would be appropriate for them to temporarily permit additional lends thru their servers beyond the number of physical copies they had previously confirmed were designated for this. As it happened, this was correct -- the books with the most number of copies lent were still lent far fewer times than the number of copies in libraries unavailable for physical lending. Nonetheless, the Internet Archive did not explicitly get permission from the libraries holding those physical copies before making the lends (due to the constraints of a worldwide pandemic). The Internet Archive also did a rather terrible job explaining and promoting the National Emergency Library, leading to considerable misunderstandings about it from authors and members of the public, some of which have persisted.

I hope this write up (and the much more detailed one in the Motion for Summary Judgement) will help explain the situation better.

#internet archive#controlled digital lending#national emergency library#cdl#nel#archive.org#libraries

1 note

·

View note

Text

#the plus side of not being able to sit due to a fistulotomy (following a colonoscopy which all was preceded by a perianal abscess)#which led into a UTI and antibiotics and has now come into what I think is the flu#(and‚ despite what my health might imply‚ is my first illness since I believe 2017)#is that if I want to draw I've got to use a pencil and I've always been faster at traditional art than digital#I think it's the lack of control offered otherwise by digital art which lends to a “fuck it good enough” traditional attitude#anyway here's a kinda fat stone the sangai#Art#Drawing#realHum#for the medical commentary lol#sangai#Manipur Eld's deer#Eld's deer#brow-antlered deer#Manipur brow-antlered deer#stone#The Stone Balancer

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dream Was Universal Access to Knowledge. The Result Was a Fiasco.

In the pandemic emergency, Brewster Kahle’s Internet Archive freely lent out digital scans of its library. Publishers sued. Owning a book means something different now.

by David Streitfeld

Information wants to be free. That observation, first made in 1984, anticipated the internet and the world to come. It cost nothing to digitally reproduce data and words, and so we have them in numbing abundance.

Information also wants to be expensive. The right information at the right time can save a life, make a fortune, topple a government. Good information takes time and effort and money to produce.

Before it turned brutally divisive, before it alarmed librarians, even before the lawyers were unleashed, the latest battle between free and expensive information started with a charitable gesture.

Brewster Kahle runs the Internet Archive, a venerable tech nonprofit. In that miserable, frightening first month of the Covid pandemic, he had the notion to try to help students, researchers and general readers. He unveiled the National Emergency Library, a vast trove of digital books mostly unavailable elsewhere, and made access to it a breeze.

This good deed backfired spectacularly.

READ MORE

Worth the long read. Covers a lot of ground. ~ eP

#internet archive#librarians#controlled digital lending#copyright#royalties#book publishers#authors#writers#common good#public domain#fair use

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

no nut november - nov 20

they put up a good fight but still couldn't make it...

(peachy had a very busy month so we're gonna ignore that this is late bc she wanted to finish it 😤)

farmer!ushijima & best friend!iwaizumi

word count: 330 & 531

cw: fem!reader, fingering, mutual masturbation, dubious consent (ushi and reader are drunk), infidelity (kind of), minors dni

farmer!ushijima

it might just be the alcohol in ushijima's veins telling him this isn't a bad idea but you're looking pretty in the dimly lit alley

he doesn't drink often but he'd thought he'd treat himself for a few at the bar after harvesting the last of his fall crops

it was a good season, one that exceeded his expectations, leaving him completely prepared for the cruelty of winter

you were already two shots in when you saw him, quickly challenging him to a drinking game and, uncharacteristically, ushijima accepted

and now the two of you are pawing at each other behind the saloon, ushijima's fingers already down your pants

and his fingers are so thick, filling you up more than your smaller digits would ever allow

"toshiii," you groaned, humping against his hand

you completely forgot about the stupid bet you made with your friends on a visit to the city last month

you were sure you could last the whole 30 days - you were single and aside from the occasional flirty jokes with a usually oblivious ushijima, there wasn't anyone else you were interested in

but now you're reaching into his jeans to pull his cock out

you're both gasping and breathing heavily into each other's mouths, desperate to get off

it feels nice to have ushijima, a massive, stoic man, groan with every flick of your wrist

you want him to cum first but once his thumb starts circling your clit, you don't stand a chance

even in the pleasure of your orgasm, you have enough sense to take care of ushijima, stroking him as the bliss racks through your body

within a few seconds, you can feel the warmth of his cum coating your hand

the two of you clean up as best as you can when ushijima mumbles, "sorry that you lost your game."

you can't help cracking up, finding it hilarious that he remembered the drunken conversation the two of you had earlier that night

best friend!iwaizumi

"uh huh," iwaizumi says, mindlessly tapping away at his controller. "no, you're so right, i can't believe he did that."

you're calling him again to complain about your boyfriend again

it was some stupid argument about whose family you were spending thanksgiving with - iwaizumi couldn't really care

"and then he just tells me to 'do whatever i want,' can you believe that?" you scoff

"no that's terrible, such a dick move," iwaizumi drones on, all of his focus on the game he's playing at the moment

every other week, you call up iwaizumi to have the same conversation with him - how much your boyfriend pissed you off and you want to break up

and, being the good friend that he is, iwaizumi lends his ear to listen (and his dick to comfort you after a breakup)

"i'm so done, he can spend thanksgiving alone. and the rest of his life for that matter," you huff but your threats hold no weight when the two of you are constantly getting back together

"can i come over? i don't want to be alone..." you ask after a few beats of silence

without thinking, iwaizumi agrees and you quickly end the phone call with a "okie dokie!! see you soon!"

it doesn't hit him for a few minutes but he suddenly remembers that he, oikawa, matsukawa, and hanamaki were doing that stupid no nut november thing again

you and your boyfriend seemed to be doing fine the whole month so and it wasn't like iwaizumi had any other prospects - not that he wanted any

but with you coming over (and being freshly single) there was no way he'd be able to keep his streak going

but iwaizumi is more disciplined than that and the two of you have been friends way before this weird....arrangement went down

he knows how to keep it in his pants and he can resist you no matter how hard you try

iwaizumi hajime is an idiot

it took less than half an hour for his dick to end up inside you

"fuck, haji, just like that!"

it was so embarrassing—your panties pushed to the side and iwaizumi's sweats scrunched only halfway down his legs

neither of you had enough patience to actually take the other's clothes off, like the moment was fleeting and could be ripped away at any time (and most of the time it felt that way)

"feels good? that's why you keep coming back, huh?" he grunts, pulling you into a kiss

you bite your lip, not wanting to admit that he was right but iwaizumi pins you to the mattress, plunging his cock deeper inside your cunt, forcing guttural moans from you

"not gonna admit it? that's fine, i already know, baby," he says, laughing when you cum around him

he follows soon after, not bothering to pull out cause he knows you enjoy the feeling of him filling you up

iwaizumi rolls off of you, taking a second to stare up at the ceiling. he knows the others will rip into him when they find out

reaching for his phone, he decides to get it over with before he helps you clean up.

©sugawarassoulmate 2023 all rights reserved - please do not repost/translate my work on other platforms!

#haikyuu smut#haikyu smut#ushijima smut#ushijima x reader#wakatoshi ushijima smut#iwaizumi hajime smut#iwaizumi smut#iwaizumi x reader#haikyuu x reader#haikyu x reader#no nut november 🍑#🥀#🥀ushijima#🥀iwaizumi#farmer!ushijima#best friend!iwaizumi

906 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a question, if you have the spoons for it. Since you're self pub, can you set your price for libraries to purchase copies of your work just like you can set your prices on other platforms? And can you choose if libraries buy a time limited license for the e-book and audiobook? Or if it's even an option for them to outright buy the digital copy of the book the same as a physical copy?

Just saw an article from my local library about how much more expensive e-books and audiobooks are from the bigger retailers and I was really confused about the massive spike from physical copy to digital copy from their chart and didn't know if it was even an option to outright buy a digital copy for the library to lend out.

(Sorry maybe this would make more sense after sleep but I am very confused about the massive price difference. Wasn't expecting digital to be 3 or 4 times more expensive and only last 2 years compared to one and done for the physical book)

You can set the price the way you would for any other retailer, yes.

However, the large spike is dependent on the library system and whether they opt for an annual digital lending license or a "renew after X amount of checkouts" license, which is not something I can control as the author/distributor.

There's no option for me to let them just buy one copy; they need the license, too.

There are other factors at play, like major publishers massively hiking the cost of their ebooks (and thus hiking the cost of the digital licenses -- which, again, varies from library to library and also from country to country), and also sometimes the distributors we use hike the prices to make sure they're still getting their cut (audiobook distribution is daylight robbery I stg), but yeah, no the digital library lending license is required.

And that license exists for physical books, too.

It might cost them less to buy a physical copy in the short term, but they're usually still obligated by a lending license to replace the book after X amount of checkouts.

334 notes

·

View notes