#christopher lasch

Text

«The assumption that our standard of living (in the broadest meaning of that term) will undergo a steady improvement colors our view of the past as well as our view of the future. It gives rise to a nostalgic yearning for bygone simplicity—the other side of the ideology of progress. Nostalgia, not to be equated simply with the remembrance of things past, is better understood as an abdication of memory. It makes the past a foreign country, as David Lowenthal puts it. It obscures the connections between the past and the present. Deeply embedded both in popular culture and in academic sociology, the nostalgic attitude tends to replace historical analysis with abstract typologies—"traditional" and "modern" society, gemeinschaft and gesellschaft—that interfere with an imaginative reconstruction of our past or a sober assessment of our prospects.

Now that we have begun to understand the environmental limits to economic growth, we need to subject the idea of progress to searching criticism; but a nostalgic view of the past does not provide the materials for that criticism. It gives us only a mirror image of progress, a one-dimensional view of history in which a wistful pessimism and a kind of fatalistic optimism are the only points of reference, a criticism of progress that depends on the contrast between complex modern societies and the close-knit communities allegedly typical of the "world we have lost," as Peter Laslett calls it in his study of seventeenth-century England.»

— Christopher Lasch: The True and Only Heaven

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you were to attend the 1939 World’s Fair, you would be greeted with two structures named Trylon and Perisphere. The former was a tall, spire-like structure equipped with what was then the world’s longest escalator. The latter was a humongous sphere. These two modernist structures were the Fair’s mascots.

By stepping into the Peripshere, a new world would be unveiled to you. Inside, a diorama of a future utopian city was constructed called “Democracity.” It was designed to be inhabited by a million and a half people, covering 11,000 square miles.

Trylon and Perisphere, along with Democracity inside, were the symbolic heart of the Fair. But the branding behind it all was intentional for more reasons than one would initially assume. The idea was created by the Fair’s publicity director, Edward Bernays. Bernays was Sigmund Freud’s cousin, known as the man chiefly responsible for bringing his psychoanalytic theories to the United States during the 1920s.

While Sigmund himself fell into despondency in Europe after World War I, Bernays became widely successful in the United States. Using ideas of the unconscious, he quickly gained a reputation as someone who could conjure up mass public opinion for products and issues like no one else. While his later critics likened it to “manipulation,” Bernays himself called it “public relations,” a term he coined.

Yet, reading his work, one finds a deeply cynical man. Bernays rationalized his activities by arguing that the management of mass desire was preferable to the alternative—that is, “letting the unconscious run wild” with its repressed urges. If these dark forces were actually unleashed, he believed, they could undo society itself. Consumerism was hence viewed as a bulwark against the primitive mind of the crowd, and managing its desires was rationalized as necessary in saving society against itself. As he stated openly in his work Propaganda (1928), “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.” He was therefore one of the first theorists of what can be called "managed democracy."

Whether he really believed in his own rationalization or not, Bernays did become incredibly wealthy from his services. By the late 1920s, he was “living in a suite of rooms in one of New York’s most expensive hotels, where he gave frequent parties.” According to an employee of Bernays, the events were a “who’s who” of the business elite, the arts, media leaders, and the mayor himself. In due time, his clients also included those within politics and the state. He became a "sort of magician" of public opinion, even though he openly viewed this same public with open contempt. Given his reputation, it was unsurprising that Bernays was tapped for the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Given that the American public was just coming out of the Great Depression, it was known that the reputation of “big business” in the United States was at historic lows. By framing the World’s Fair through the prism of desire, Bernays sought to rehabilitate this perception by giving Americans an open door—one that they themselves did not even know they wanted. Bernays’s daughter confirms this aspiration of his in an interview with Adam Curtis for his documentary A Century of the Self (2002).

Anna Bernays: To my father, the World’s Fair was an opportunity… Capitalism in a democracy, democracy and capitalism in marriage. It was consumerist, but at the same time you inferred in a funny way that democracy and capitalism went together.

Adam Curtis [continues]: The vision it portrayed was of a new democracy in which businesses responded to people’s innermost desires in a way politicians could never do. But it was a form of democracy that viewed people not as active citizens… but as passive consumers… [which] Bernays believed was the key to control in a mass democracy.

As Curtis makes clear, this thinking reached its symbolic high point at the 1939 World’s Fair. A democratic vision was then constructed by its very own skeptic, someone who viewed democracy as nothing other than a form of social management. Historian of public relations, Stewart Ewen, summarized this view in an interview with Adam Curtis:

“It’s not that the people are in charge, but that the people’s desires are in charge. The people exercise no decision-making power within this environment. So democracy is reduced from something which assumes an active citizenry to the idea of the public as passive consumers driven primarily by instinctual or unconscious desires, and if you can trigger those needs and desires, you can get what you want from them.”

At the end of the century, the consequences of this vision would be criticized by writer Christopher Lasch. Published after his death in 1994, Lasch wondered whether American democracy was now merely living off the “borrowed capital of moral and religious traditions antedating the rise of liberalism." Lasch was a critic of the kind of managed democracy that began to emerge around Bernays's time. By the 1990s, the consequences had become self-evident: when Lasch was writing, civic participation had sunk to its lowest point since World War II.

Perhaps this long trajectory—triumphantly advertised as a "new horizon" at the 1939 World’s Fair—helps explain why the state’s competency and ability to execute basic functions has deteriorated so badly in our own time. Needless to say, Bernays's model of managed democracy was not exactly resilient and built to last.

Decades later during the 1970s, optimism would dry up amid scandal as institutional trust collapsed, exposing the hollowness of this consumer model of democracy outright for the first time. The fact that the United States has still not recovered from that “crisis of confidence” is not accidental: the ultimate outcome of a Bernaysian model of managed democracy is not renewal amid crisis, but rather an entrenchment of its old managerial ways, because it has so little of an active public to draw upon.

#1939 40 world's fair#worlds fair#1939 worlds fair#1939#democracy#capitalism#edward bernays#christopher lasch#progress#futurama#public relations#managed democracy#the beginning of the end#america#substack#sigmund freud#propaganda#propagandists

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

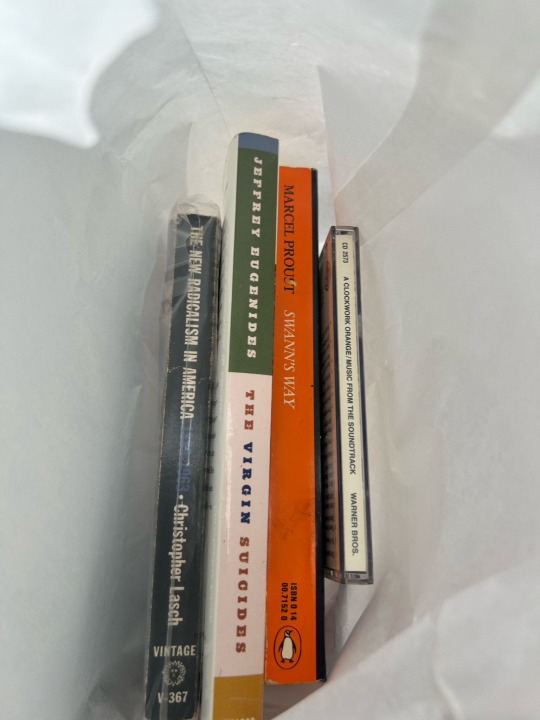

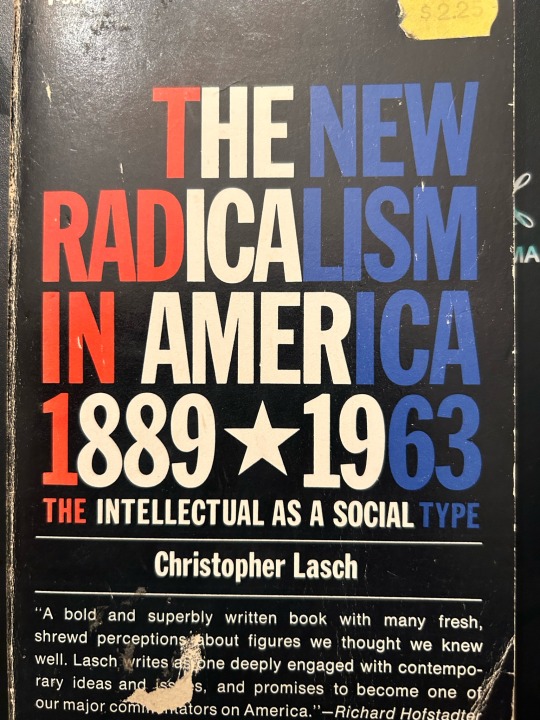

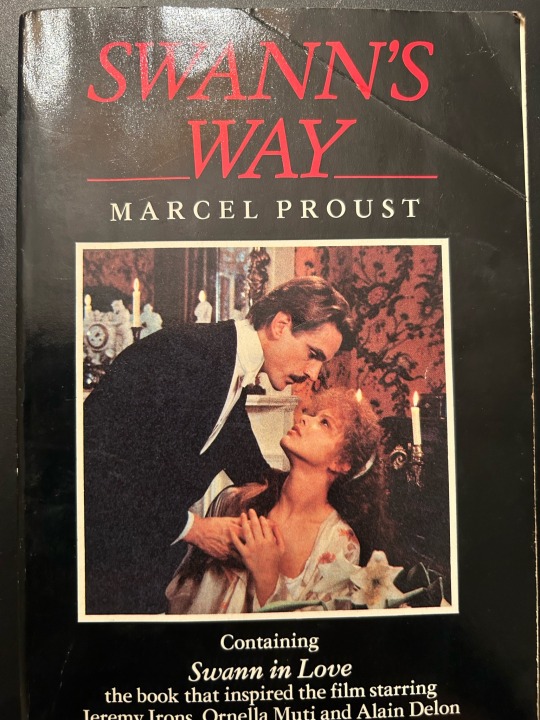

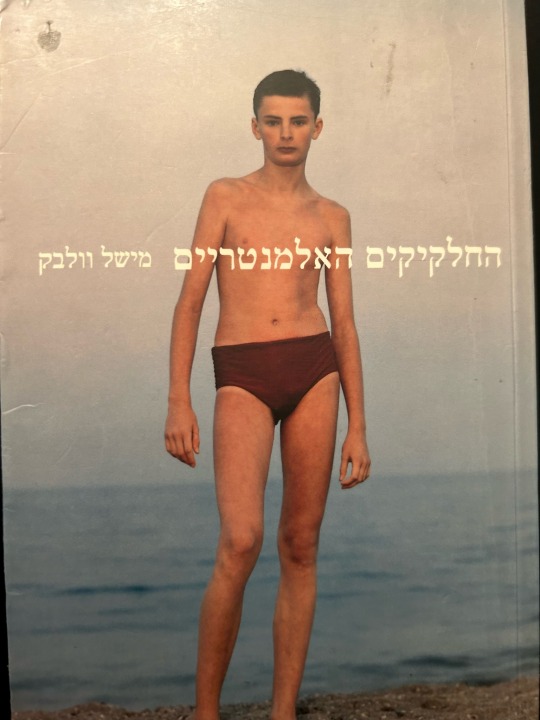

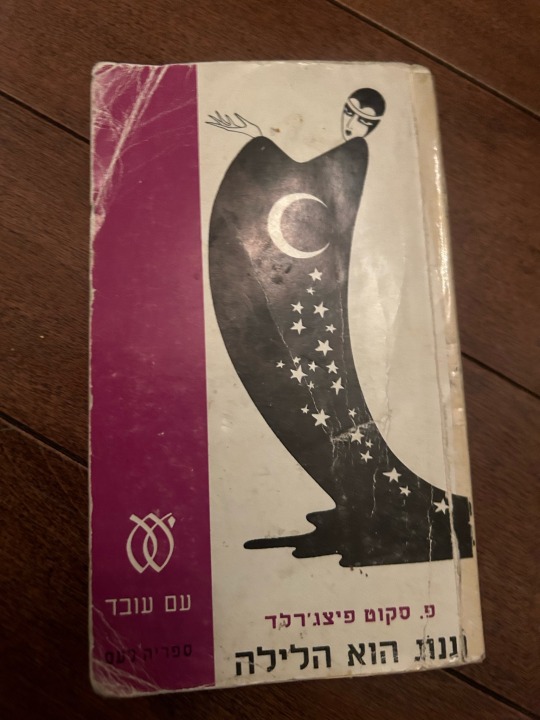

Good ass haul

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In a dying culture, narcissism

embodies the highest attainment

of spiritual enlightenment.

— Christopher Lasch

[Poetic Outlaws]

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

If the 70s are back, does that vindicate the red scare girls in their promotion of lasch?

The Lauren Duca trajectory described in the Compact article pretty clearly demonstrates the early Red Scare thesis that leftist radicalism was neoliberal narcissism in disguise. Though, confession, I've never actually read The Culture of Narcissism, just The New Radicalism in America and The Revolt of the Elites among Lasch's books, both of which were more capital-P political than psychological in nature. I wonder how the girls' current trajectory refracts this question. Anna's advocacy of open, grandiose narcissism is perhaps not what the self-styled Jeffersonian populist Lasch had in mind, though I find it personally sympathetic.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ Mentre la vita pubblica e persino quella privata assumono i caratteri dello spettacolo, è in atto un contromovimento che cerca di modellare lo spettacolo, il teatro, tutte le forme di espressione artistica, sulla realtà — di annullare la differenza stessa tra arte e vita. Entrambe le tendenze diffondono un senso dell’assurdo caratteristico della sensibilità contemporanea. Va notata la stretta connessione tra un eccesso di elementi spettacolari, il cinismo dell’atteggiamento disincantato ormai diffuso anche tra i bambini, l’impermeabilità alla sorpresa o alle emozioni violente e la conseguente indifferenza a distinguere tra illusione e realtà.

Siamo troppo ciniche [scrive Joyce Maynard di se stessa e di una bambina di quattro anni che ha portato al circo], per non intuire il trabocchetto nel gioco di prestigio, l’imbottitura del Santa Claus dell’Esercito della Salvezza, i trucchi della telecamera negli show pubblicitari alla TV (“Non è la mano di un folletto che spunta fuori dalla lavatrice,” mi dice Hanna, “è soltanto un attore coi guanti.”) Non diversamente al circo... ella si appoggiò indietro sul sedile imbottito, la mia bambina di quattro anni... prevedendo capitomboli e scivoloni, severa, sveglia, triste, saggia, matura, disincantata, più assorta nello zucchero filato che affascinata dal Più Grande Spettacolo del Mondo. [...] Avevamo assistito, impassibili, a spettacoli ben più straordinari, tutto il nostro mondo era un’indigestione per gli occhi, un circo a dieci piste con cui non avrebbero potuto competere neppure i Ringling Brothers. Un uomo ficcò la testa nelle fauci di una tigre e io lo indicai alla mia gelida, imperturbabile amica, con espressioni di sbalordimento esagerato, e quando essa non si curava di guardare... le giravo la testa verso la tigre, la costringevo a seguire il numero. La tigre, penso, avrebbe potuto staccare la testa al domatore con un morso, inghiottirlo in un boccone e tramutarsi in scimmia e lei non avrebbe battuto ciglio. Davanti a noi almeno due dozzine di clown ammucchiati in una Volkswagen cercavano di uscirne senza che Hanna capisse qual era lo scopo di tutto ciò. Non è solo perché sa che escono da una botola che Hanna non riesce a entusiasmarsi. Anche se non fosse a conoscenza del trucco, non dimostrerebbe maggiore interesse.

La sovraesposizione a illusioni prefabbricate distrugge rapidamente la loro efficacia rappresentativa. La componente illusoria del reale non produce, come sarebbe prevedibile, una intensificazione del senso della realtà, ma genera, nei confronti della realtà stessa, uno stato di allarmante indifferenza. Il nostro senso della realtà si trova allora a dipendere, per quanto sembri strano, dalla nostra disponibilità ad accettare l’aspetto illusorio del reale. Persino la comprensione razionale delle tecniche illusorie non annulla la nostra capacità di considerare l’illusione prodotta come una rappresentazione della realtà. La smania di conoscere i trucchi del prestigiatore, come l’interesse suscitato recentemente dagli effetti speciali di un film quale Guerre stellari, hanno in comune con lo studio della letteratura il desiderio di apprendere dai maestri dell’illusione lezioni sulla realtà stessa. Ma quando si riscontra un’indifferenza totale persino per la meccanica dell’illusione, è prevedibile il collasso della stessa idea di realtà, che dipende in ogni suo elemento dalla distinzione tra natura e artificio, realtà e illusione. Tale indifferenza rivela l'erosione della capacità di interessarsi a qualsiasi cosa esterna al sé. Così la bambina impassibile, che ha già visto tutto, si riempie di zucchero filato e quanto succede non le importerebbe neppure se non sapesse in che modo ventiquattro clown riescono a infilarsi in una macchina. “

Christopher Lasch, La cultura del narcisismo. L’individuo in fuga dal sociale in un’età di disillusioni collettive; Nuova postfazione dell’autore, traduzione di Marina Bocconcelli, Fabbri (collana Saggi Tascabili), 1992. [Libro elettronico]

[Edizione originale: The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations, W. W. Norton, New York City, 1979]

#Christopher Lasch#La cultura del narcisismo#libri#leggere#società americana#individualismo#sociologia#saggistica#società dello spettacolo#teatro#forme d'arte#assurdo#vita#atteggiamento disincantato#disincanto#cinismo#bambini#Esercito della Salvezza#Santa Claus#circo#clown#noia#sospensione dell'incredulità#realtà#illusione#infanzia#sospensione del dubbio#indifferenza#Guerre stellari#letteratura

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

God, not culture, is the only appropriate object of unconditional reverence & wonder.

Christopher Lasch

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

«When debate becomes a lost art, information, even though it may be readily available, makes no impression.»

- Christopher Lasch

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Oggi quasi tutti ammettono che il progresso

- almeno nella sua forma utopistica -

è una "superstizione" quasi "esaurita"

“Il paradiso in terra”, C. Lasch

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

We demand too much of life, and too little of ourselves.

Christopher Lasch

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Massmedierna har med sin kult av kändisskap och sina försök att omge kändisskapet med glans och spänning gjort amerikanerna till en nation av beundrare och biotittare. Massmedierna ger innehåll åt de narcissistiska drömmarna om ära och berömmelse och förstärker dem därigenom; de uppmuntrar den enkle medborgaren att identifiera sig med stjärnorna och att avsky "hopen" och gör det allt svårare för honom att acceptera det triviala i den vardagliga tillvaron.

Christopher Lasch, Den narcissistiska kulturen

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amidst the raft of lamentations of the decline of civic commitment and public life that ensued during the crisis of the 1970s, Lasch’s intervention is of special interest. He portrayed the growth of the ‘culture of narcissism’ as specifically bound up with the rise and decline of 1960s’ radicalism. This could of course hardly claim to be critique of American political culture at large: the generous bribes and bailout packages which permitted the comfortable hedonism that so appalled him were available only to a small part of the American population. In other words, his sermons were addressed specifically to progressive elites, faulting them for succumbing to the temptations of consumerism and their inability to shoulder the responsibilities of prudent leadership. It was as if the American population at large was too far gone for help and as if America’s real, and potentially still treatable, problem was the spread

of consumerism and individualism to the progressive class.

Meanwhile, those segments of the American population that Lasch had little interest in talking to or about, far from being mired in consumerist indulgence, were in the process of adapting themselves to changing economic imperatives. And in this context a neoliberal ethos emerged that found tremendous popular traction (Konings, 2009). While it was just as critical of narcissistic selfhood, it viewed this not as an effect of the decline of progressivism but precisely as a natural outcome of the progressive mindset, its elitist paternalism, and the lazy, hedonistic sense of entitlement this had fostered. This meant that there was something highly unreflexive about Lasch’s intervention: he seemed oblivious that the very sentiments that he expressed were typically targeted precisely at him and his progressive brethren and that an entire political movement

was being built on that logic. In this way, he illustrated how thoroughly technocratic, elitist, and disconnected from popular concerns progressive thought had become.

Martjin Konings, "Imagined Double Movements: Progressive Thought and the Specter of Neoliberal Populism"

#martjin konings#christopher lasch#marxism#liberalism#united states#neoliberalism#polyani#karl polyani

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Lasch: 'Nostalgia'

“A society that has made “nostalgia” a marketable commodity on the cultural exchange quickly repudiates the suggestion that life in the past was in any important way better than life today. ”—Christopher Lasch.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

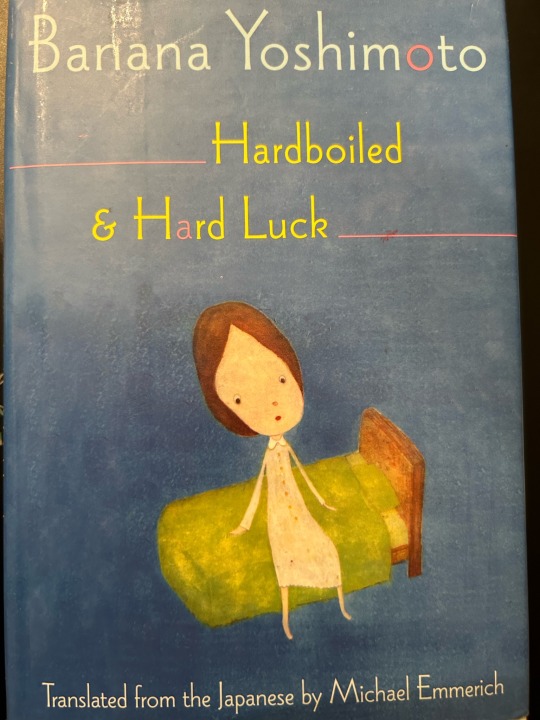

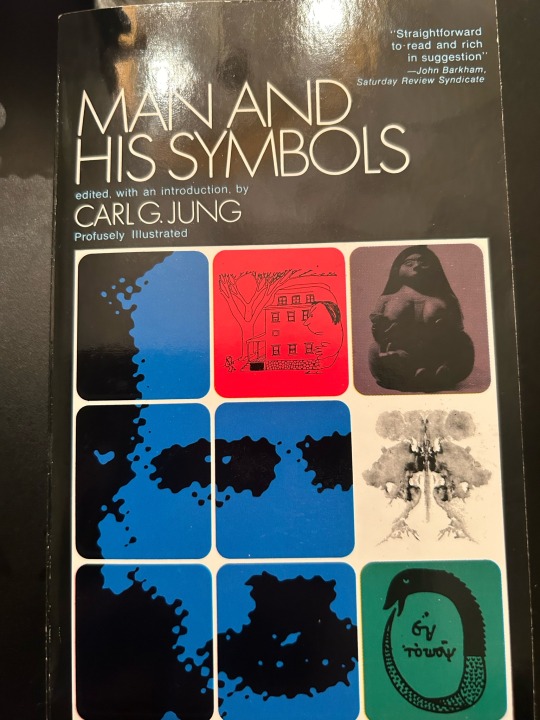

Books to read

#f scott fitzgerald#michel houellebecq#friedrich nietzsche#zizek#carl jung#marcel proust#virgin suicides#banana yoshimoto#christopher lasch#french books

1 note

·

View note

Text

“ Il ruolo dei mass media nella manipolazione dell'opinione pubblica è stato oggetto di grande e preoccupata attenzione, ma per lo più mal indirizzata. Molti giudizi critici partono dal presupposto che il problema sia quello di impedire la circolazione delle falsità palesi; mentre è evidente, come è stato messo in luce dalle più acute analisi della cultura di massa, che i mass media, diffondendosi, hanno reso non pertinenti, per una valutazione della propria influenza, le categorie di vero e falso. La verità ha lasciato il posto alla credibilità, i fatti alle affermazioni che suonano autorevoli senza convogliare alcuna informazione autorevole.

Proclamare che un dato prodotto è preferito dalle persone importanti senza dire a che cosa è preferito, vantare la superiorità di un prodotto su concorrenti non specificati, attribuire implicitamente una data caratteristica unicamente al prodotto reclamizzato quando di fatto essa è condivisa da quelli della concorrenza, sono altrettanti espedienti per offuscare la distinzione tra vero e falso in un polverone di plausibilità. Questo genere di associazioni sono “vere”, ma totalmente mistificanti. L’addetto stampa del presidente Nixon, Ron Ziegler, fornì un significativo esempio dell'uso politico di queste tecniche quando ammise che le sue precedenti affermazioni sull'affare Watergate erano diventate “inoperative”. A molti questo sembrò un modo eufemistico di riconoscere di aver mentito. Ciò che in realtà Ziegler voleva dire, era che le sue primitive dichiarazioni non erano più attendibili. Non il loro essere false, ma la loro incapacità di convincere le rendeva “inoperative”. La loro veridicità o meno non era in discussione. “

Christopher Lasch, La cultura del narcisismo. L’individuo in fuga dal sociale in un’età di disillusioni collettive; Nuova postfazione dell’autore, traduzione di Marina Bocconcelli, Fabbri (collana Saggi Tascabili), 1992. [Libro elettronico]

[Edizione originale: The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations, W. W. Norton, New York City, 1979]

#Christopher Lasch#leggere#libri#letture#saggistica#saggi#La cultura del narcisismo#mass media#informazione#notizie#politica americana#sociologia#ermeneutica#verità#falsità#opinione pubblica#menzogna#Watergate#pensiero critico#Marina Bocconcelli#Richard Nixon#Ron Ziegler#propaganda#intellettuali americani#manipolazione#mistificazione#politici#Psicologia delle folle#cultura di massa#persuasione

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Narcissistic Culture of “Image” and Excessive Self-Monitoring

In a world obsessed with public image and attention-seeking, learn about the cultural forces propelling society to become more narcissistic – and how this influences us to be in a constant state of self-scrutiny.

Learn more!

#Psychology#Culture#Society#Books#Narcissism#Self-Monitoring#Image#Culture of Narcissism#Christopher Lasch

1 note

·

View note