#black doctors

Text

#butterflikisses#black twitter#blackout#black women#blackcouples#kdthoughts#twitter thoughts#butterflikisses twitter thoughts#black men#black positivity#successful black women#black doctors

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Women in the Medical/Healthcare Field 🏥👩🏾⚕️🩺🥼💉💊

#black girl moodboard#black girl aesthetic#nurses#healthcare#medical field#poc aesthetic#girl aesthetic#pretty girl aesthetic#dream life#dream job#vision board#manifesting#manifestation#black girl vision board#black woman appreciation#black doctors#black nurses#healthcare workers

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black people#black community#black art#original photographers#black culture#artwork#graphic design#black family#black power#black history#black woman#black success#black doctors

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

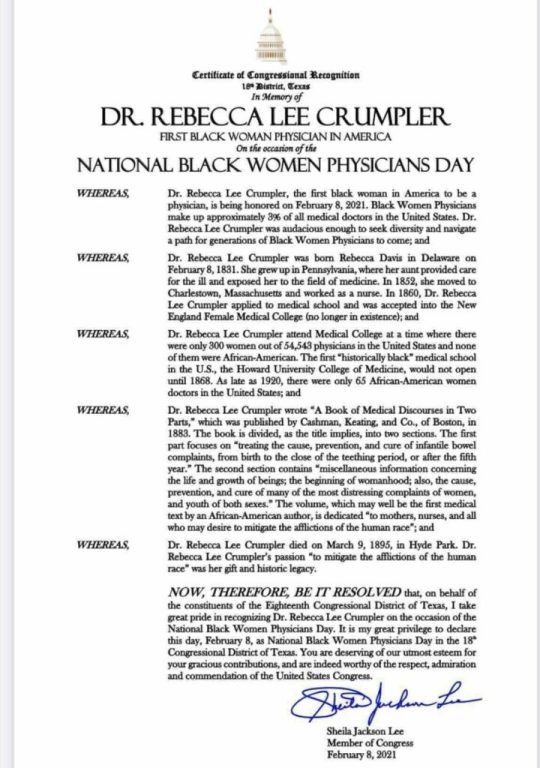

Rebecca Lee Crumpler was also one of the first female physician authors in the nineteenth century.

In 1883, she published A Book of Medical Discourses. The book has two parts that cover the prevention and cure of infantile bowel complaints, and the life and growth of human beings. Dedicated to nurses and mothers, it focuses on maternal and pediatric medical care and was among the first publications written by an African American on the subject of medicine.

She made a number of contributions these societies, and the Massachusetts Medical Society. She was the first woman and/or person of color elected President of the Society of Academic Anesthesiology Chairs. Her legacy includes training over 100 anesthesiologists.

Crumpler was subject to "intense racism" and sexism while practicing medicine. During this time, many men believed that a nearly immutable difference in average brain size between men and women explained the difference in social, political, and intellectual attainment.Because of this, many male physicians did not respect Rebecca Lee Crumpler, and would not approve her prescriptions for patients or listen to her medical opinions.

Read more about her here!

V

V

V

#lgbt#human rights#humanity#leftist#lgbtq#history#love#black herstory#black woman#black history#blacklivesmatter#black women#black history month#black doctors#first black woman to become a doctor#doctor#medicine#african american history#heritage#autism#socialism#leftism#social justice

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

STAT: In counties with more Black doctors, Black people live longer, 'astonishing' study finds

Black people in counties with more Black primary care physicians live longer, according to a new national analysis that provides the strongest evidence yet that increasing the diversity of the medical workforce may be key to ending deeply entrenched racial health disparities.

The study, published Friday in JAMA Network Open, is the first to link a higher prevalence of Black doctors to longer life expectancy and lower mortality in Black populations. Other studies have shown that when Black patients are treated by Black doctors, they are more satisfied with their health care, more likely to have received the preventive care they needed in the past year, and are more likely to agree to recommended preventive care such as blood tests and flu shots. But none of that research has shown an impact on Black life expectancy.

The new study found that Black residents in counties with more Black physicians — whether or not they actually see those doctors — had lower mortality from all causes, and showed that these counties had lower disparities in mortality rates between Black and white residents. The finding of longer life expectancy persisted even in counties with a single Black physician.

“That a single Black physician in a county can have an impact on an entire population’s mortality, it’s stunningly overwhelming,” said Monica Peek, a primary care physician and health equity researcher at UChicago Medicine who wrote an editorial accompanying the new study. “It validates what people in health equity have been saying about all the ways Black physicians are important, but to see the impact at the population level is astonishing.”

“This is adding to the case for a more diverse physician workforce,” said Michael Dill, the director of workforce studies at the Association of American Medical Colleges and one of the study co-authors. “What else could you ask for?”

Lisa Cooper, a primary care physician who directs the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity and has written widely on factors that may explain why Black patients fare better under the care of Black doctors, called the study “groundbreaking” and “particularly timely given the declining life expectancy and increasing health disparities in the U.S. in recent years.”

“These findings should serve as a wake-up call for health care leaders and policymakers,” she told STAT.

The team of researchers, from the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the AAMC, started their work by analyzing the representation of Black primary care physicians within the country’s more than 3,000 counties during 2009, 2014, and 2019. Even this first step resulted in a stark finding: Just over half of the nation’s counties had to be excluded from analysis because they contained not a single Black primary care physician.

“I knew it was a problem,” said Dill, “but ooh, those numbers are not good.”

The team’s analysis of the 1,618 counties that had at least one Black primary care physician in one of the three years found that the more such physicians a county contained, the higher life expectancy was for Black residents. (They’d like to repeat the analysis in the future to see how counties with Black doctors fared during the Covid-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affected people of color.)

The team found life expectancy increased by about one month for every 10% increase in Black primary care physicians. While extending life by a few months may not sound like much given that the life expectancy gap between Black and white Americans nationally is nearly six years, picking up such a signal on a population level is significant, the authors said.

The study found that every 10% increase in Black primary care physicians was associated with a 1.2% lower disparity between Black and white individuals in all-cause mortality. “That gap between Black and white mortality is not changing,” said John Snyder, a physician who directs the division of data governance and strategic analysis at HRSA and who was one of the lead authors. “Arguably we’ve found a path forward for closing those disparities.”

The study did not directly address the reason Black people fare better in counties with more Black physicians, nor does it prove a cause-and-effect relationship. While earlier research suggests “culturally concordant” medical care is of better and higher quality for patients, the new study indicates that one factor may be that Black physicians are more likely to treat low-income and underinsured patients, taking on new Medicaid patients more than any other racial or ethnic group, for example. The study found that improvements in life expectancy were greatest in counties with the highest rates of poverty.

“I wasn’t expecting that,” said Rachel Upton, an HHS statistician and social science analyst who was one of the report’s lead authors. “It shows having Black physicians is not only helpful across the board, but it’s particularly useful with counties with high poverty.”

Many studies have found that communication is improved when patients and physicians are of the same race. Owen Garrick co-authored a 2019 study in Oakland, Calif., finding that cardiovascular disease could be curbed more in Black patients who are seen by Black doctors because they are more likely to engage in preventive health care. He noted during his study that Black patients were not only more likely to talk with Black doctors about subjects like upcoming birthday parties or weddings, they were also more likely to invite them to the events.

But good communication is not the only factor: A 2020 study found that in infant care, where verbal communication from the doctor is not an issue, mortality rates for Black infants were reduced when they were treated by Black physicians; the authors suggested stereotyping and implicit bias may play a role when doctors treat patients outside their racial and ethnic groups.

The current study looked past the patient-doctor relationship and showed that patients may fare better simply by living in counties with Black doctors even if they are not directly treated by those doctors. Living in a county where Black doctors work and thrive “may be a marker for living in a community that better supports Black lives,” Snyder said.

Another factor, said Peek, is that Black physicians may be more likely to do unpaid health-related work outside of the health care system, such as providing expertise to community organizations, being politically involved in health-related matters, and encouraging medical societies to advocate for public health.

That’s the case with Peek, who has spent two decades working with a nonprofit that helps Black women in public housing become health navigators and advocates. She also spends a good deal of time providing a second opinion to her network of friends and family — and their friends and families — who do not personally know any physicians and may have issues of mistrust with the medical system.

“With my non-Black colleagues, it’s like ‘Both my parents were doctors! Everyone’s a doctor!’” she said. “Their social network is not all paranoid when they enter the health care system.”

She said the study also pointed to problems with racism within medicine and bias toward Black patients that has created a “chasm” between non-Black physicians and their Black patients. She’s struck, she said, by the number of Black people who come up to her after she speaks at a local church to give her their detailed medical history and ask her opinion because they don’t trust their own medical team. “I look like them,” Peek said. “They trust I have their best interest at heart.”

The authors of the new paper said they were not advocating segregated care and all doctors should improve their cultural competency. Patients of all races and ethnicities would be helped by increased diversity in the physician workforce, they said.

But increasing the number of Black physicians remains a stubborn problem. Despite decades of attention to the matter, a 2021 study showed the number of Black and Native American medical students, particularly males, has stagnated. The AAMC has reported a recent uptick in admissions of Black medical students, possibly due to a renewed focus on diversity in recent years, but an upcoming Supreme Court decision expected to limit the use of race as a factor in admission could cut into such gains.

The current study did not address how the presence of physicians from other groups underrepresented in medicine, including Hispanic and Indigenous people and Pacific Islanders, affects health outcomes. Upton said she hoped other researchers could focus on such groups in the future and that more researchers would conduct “within group” studies to examine the health of people within a single racial or ethnic group and not just examine how such groups compare to other, usually white, populations.

“Oftentimes we just look at the disparities,” she said. “I would like people to be looking at how people are doing within their own groups and what can help within those groups.”

#Black Doctors#Black Life#Black Healthcare#In counties with more Black doctors#Black people live longer#Black Healthcare with Black Doctors

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black children deserve better . Stop pushing your lost dreams and societal ideas on to them

#black power#knowledge#black knowledge#conscious parenting#parenting#black parents#black families#black family#black children#black doctors#black lawyers#african

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

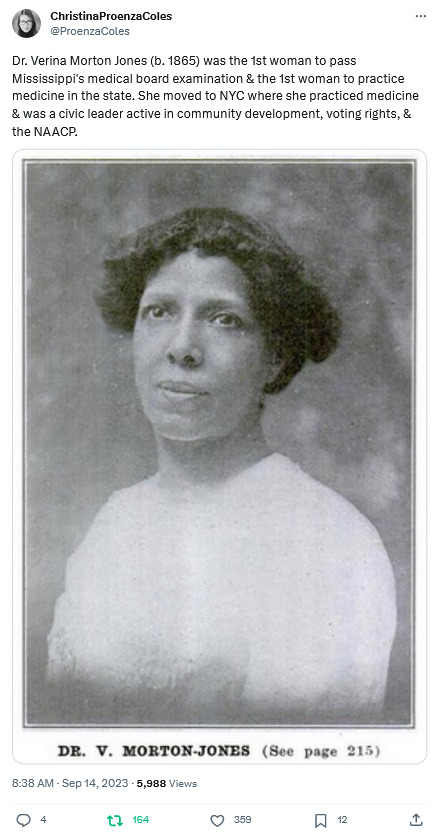

https://x.com/ProenzaColes/status/1702300841359663436?t=yP3mcQOIal4Dz3qI9Kr4tA&s=09

#Verina Morton#Dr V Morton Jones#First Black Female Freedmen Physician in Mississippi#Mississippi#Black Doctors#NYC

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s an older livestream but is resurfacing because of her recent sit-down with VP Harris (that “conversation” made people question why her points seemed so odd in addition to not very much action or solution was provided).

Dr. Jackie Walters…it is absolutely deplorable, dangerous and anti-Black that this sentiment is her actual feelings. She is part of the problem and for it to come from an actual Black (woman) OB-GYN is heinous. It’s scary. Putting more Black mothers at risk with these insane generalizations and stereotypes. (I see some folks saying because she herself has not had children that she wouldn’t know…it should not have to be because you can’t relate with not having children of your own that you somehow can’t be empathetic)!

“A bit more dramatic” and “cry wolf”. I’m heated!

I don’t care if that pregnant soon to be mommy comes to you twice a day for thirty days straight! There is a literal life growing inside of her. You don’t know what her body is experiencing (I mean, yes you do as a physician but it also is very personalized)! You should care for her well-being and her unborn’s well-being at every turn. Ease her concerns by showing compassion and empathizing AND most importantly assuring her that she’s being heard. And these women are selectively choosing you because you are a Black OB-GYN and a woman —assuming they’ll get better care given the horror stories we consistently hear when the physician isn’t Black and isn’t a woman.

The “a bit more dramatic” is probably because of your sentiments! So then consistently never being heard or taken seriously results in Black mothers-to-be having no choice but to be overly expressive in making their voices heard!

We know the stories of other Black pregnant women (non-famous & famous alike). We know the stats. We know the racism Black women receive from health care personnel who are not Black. We know the bias. We know the systemic racism and implicit bias. We know this all and it’s sickening to hear this come from her. Her Anti-Blackness is harmful.

((and taking days off from work during a woman’s pregnancy…wouldn’t that be the best time to use pto?? taking off a day or more is ideal during pregnancy. some jobs are already stressful as it is and showing up to work while also pregnant is double that for expecting mothers. what business is it of yours that she needs to request days off—she earned that))

#Black doctors#Black maternal mortality#Black mothers#Black pregnancy#birthing#Dr Jackie Walters#Jackie Walters#Black pregnancies#Black expecting mothers#infant mortality#health care#health industry#married to medicine

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Charles Prudhomme

Dr. Charles Prudhomme, the first Black Vice President of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and artist, Mrs. Naida Willette Page, present a portrait of Solomon Carter Fuller, MD, the first Black member of APA, in 1971.

Dr. Prudhomme commissioned the portrait as a gift to the Association.

Charles Prudhomme, M.D. (1908–1988), an African-American physician and psychoanalyst, entered the field of psychiatry in the 1930s. He served as the vice president of the American Psychiatric Association in 1970-1971, the first African-American to gain elected office in the organization.[1]

Prudhomme was born in Opelousas, Louisiana. When Prudhomme was three years old, his father developed tuberculosis, and the family moved to Denver, Colorado. Along the way, the family stopped in Kansas City, Missouri where Prudhomme and his mother stayed while his father continued to Denver. Prudhomme received his schooling in Kansas City, became a baseball player, and graduated from high school second in his class.

Prudhomme entered the University of Kansas but remained for only a short time. Due to segregation laws…[Read more here]

Sources: Wikipedia, American Psychiatric Association Foundation, Jet magazine

Visit www.attawellsummer.com/forthosebefore to learn more about Black history.

Need a freelance graphic designer or illustrator? Send me an email.

#Charles Prudhomme#Louisiana history#American Psychiatric Association#Black doctors#Black physicians#psychoanalyst#psychiatric#psychiatry#Solomon Carter Fuller#mental health#Naida Willette Page#Louisiana#Opelousas#segregation#Black history#Washington#DC#Howard University#HBCs

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Doctors and the Legacy of Racism in Medicine

Before we get to the AI - go buy "Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in Medicine" by Uche Blackstock. She's a high school classmate of mine and on a recent AI panel I was on I told people that I thought should be required reading ( The other book I made required reading were "Weapond of Math Destruction " and " Unmasking bias" ) Why should book not explicitly about AI be required reading for those involved with AI? One of the major dangers in AI is that it uses data that contains bias from our current society to predict future outputs/outcomes. So if we don't understand the racism and bias that is in medicine right now, using AI anywhere in healthcare essentially calcifies these biases behind opaque mechanical systems.

Here's what Perplexity says about the book:

"Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in Medicine" is a memoir by Dr. Uché Blackstock, an emergency medicine physician and CEO dedicated to dismantling racism in healthcare. The book delves into the historic health care inequities and systemic racism, detailing Dr. Blackstock's family legacy of black female physicians and her own experiences as a physician and patient. It offers a searing indictment of the U.S. healthcare system, serving as a generational family memoir and a call to action. The book sheds light on the profound and long-standing systemic inequities that lead to far worse health outcomes for Black Americans and endangers the well-being of communities. It also addresses the flawed system that hampers the progress of Black patients and physicians, making it a compelling and necessary read for healthcare professionals, policymakers, and the general public[1][2][3].

Citations:

[1] https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/66087028

[2] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-black-physicians-memoir-looks-at-the-legacy-of-medical-racism-in-america

[3] https://www.harvard.com/book/9780593491287_legacy/

[4] https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/705871/legacy-by-uche-blackstock-md/

[5] https://www.amazon.com/Legacy-Physician-Reckons-Racism-Medicine/dp/0593491289

So for today I wanted to highilight some other achievements of black doctors:

Some notable black doctors in American history include:

Dr. James McCune Smith (1813–1865): He was the first black American to earn a medical degree and practice in the United States. He also opened what is thought to be the country's first African American-owned pharmacy[3].

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831–1895): She became the first black woman in the United States to receive an MD degree. After the Civil War, she moved to Richmond, Virginia, where she worked with other black doctors caring for formerly enslaved people in the Freedmen’s Bureau[2][3].

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (1856–1931): He founded Chicago’s Provident Hospital, the country’s first black-owned, interracial hospital, and performed the first-ever successful heart surgery two years later[3].

Dr. Charles Richard Drew (1904–1950): Known as the "father of blood banking," he pioneered blood preservation techniques that led to thousands of lifesaving blood donations[3].

Dr. Louis Wade Sullivan (b. 1933): He became the founding dean of what became the Morehouse School of Medicine, the first predominantly black medical school[2].

Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller: He was the first black psychiatrist in the United States and became an authority on Alzheimer’s Disease research[3].

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston: She published a study of sickle-cell anemia that led to a nationwide test for newborns and became the first African American and female director of a public health bureau[3].

These doctors overcame significant challenges, including racism and prejudice, and made pioneering contributions to the field of medicine in the United States[2][3].

Citations:

[1] https://www.everydayhealth.com/healthy-living/african-american-pioneers-who-changed-healthcare/

[2] https://www.aamc.org/news/celebrating-10-african-american-medical-pioneers

[3] https://www.auamed.org/blog/african-american-doctors/

[4] https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/blackhistorymonth/chronology

[5] https://interestingengineering.com/lists/black-doctors-medicine

From Gemini: Pioneering Healers: A Glimpse into the Lives and Achievements of African American Doctors

From overcoming systemic barriers to making groundbreaking contributions, African American doctors have woven a remarkable tapestry of resilience, dedication, and excellence within the annals of medicine. Their stories, etched in struggle and triumph, not only illuminate their individual journeys but also shed light on the broader fight for racial equality in the United States.

The earliest documented Black physician in America, James Durham, emerged during the tumultuous years of the Revolutionary War. Denied formal medical training due to his race, he honed his skills through apprenticeships and self-study, eventually serving Continental Army soldiers and establishing a successful practice in New Orleans. Dr. Durham's story exemplifies the resourcefulness and determination that characterized countless Black medical pioneers.

Throughout the 19th century, figures like David Augustus Chisolm, the first Black graduate of Harvard Medical School, and Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first Black woman to earn an M.D. in America, defied prejudice and carved their own paths. They faced not only societal discrimination but also limited access to education and resources. Yet, their unwavering commitment to serving their communities propelled them forward, paving the way for future generations.

The 20th century witnessed a surge in Black medical advancements. Dr. Charles Drew, known for his groundbreaking work on blood plasma storage, revolutionized wartime medicine and saved countless lives. Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown, the first Black resident at New York Hospital, became a prominent surgeon and advocate for healthcare equity. Their achievements resonated far beyond the medical field, serving as powerful symbols of Black excellence and defying long-held stereotypes.

However, the journey towards equality has been fraught with challenges. Despite their qualifications and contributions, Black doctors have historically faced discrimination in hiring, promotions, and access to funding. The fight for equal opportunities continues, with disparities in healthcare access and representation still prevalent today.

Yet, the legacy of African American doctors remains an inspiration. Their unwavering dedication to healing, coupled with their courage in the face of adversity, serves as a testament to the enduring human spirit. Their stories remind us of the vital role they have played in shaping American medicine and underscore the continued need for equity and inclusion in the healthcare system.

Reading List:

"Black Doctors in White America: Mobilization & Progress During World War II" by Charles W. Eagles

"Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present" by Harriet A. Washington

"A Sickness in Our Land: Epidemics in the Atlantic World" by Virginia DeJohn Anderson

"Black Women Scientists in the United States" by Evelyn Fox Keller

"Charles R. Drew: The Man Who Saved the Blood" by Catherine Reef

"Dorothy Lavinia Brown: The Untold Story of the First Black Woman Surgeon" by Jessica M. Dorman

"Between Slavery and Freedom: Women of Color in the Civil War Era" by Stephanie Camp

"Medical Bondage: From Cotton to Crack" by Harriet A. Washington

"Black Skin, White Masks" by Frantz Fanon

"The Souls of Black Folk" by W.E.B. Du Bois

"Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America" by Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton

"Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health" by Ivan Illich

"The Color of Violence: The Incarceration of the Innocent and the Making of an American Epidemic" by Evelyn Hoenig Jarvis

"Medical Racism: Race, Ethnicity, and Health Care in the United States" by Carlos V. Hill

"Do Black Patients Get the Same Care? Understanding Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care" by Charles R. King

"Unbroken: A Story of Strength, Faith, and Survival in the Ever After" by Laura Hillenbrand

"Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race" by Margot Lee Shetterly

"The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" by Rebecca Skloot

"Educated" by Tara Westover

"Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents" by Isabel Wilkerson

This list, though not exhaustive, offers a diverse range of perspectives on the experiences and contributions of African American doctors within the broader context of American history and social justice. Through these voices, we gain a deeper understanding of their struggles, triumphs, and enduring legacy in the field of medicine.

It is important to note that the experiences of African American doctors are diverse and cannot be homogenized. This reading list attempts to offer a general overview of the topic, but further exploration into specific individuals and historical periods is encouraged.

#black history month#blackhistorymonth#equality#dalle3#africanamericanhistory#black doctors#Legacy#Weapons of Math destruction#Unmasking bias

1 note

·

View note

Note

Do you believe that if a woman or girl requests a female gynaecologist, and the gyno is a pre-transition trans woman, the patient is transphobic for being uncomfortable or asking for a cis woman doctor? Genuine question

Is it transphobic to dismiss the services of a transgender doctor because she is trans?

Petra De Sutter is a gynecologist and politician, currently serving as the federal Deputy Prime Minister of Belgium. Would it be OK for a cis woman to ask for another female gynecologist, if Petra was the one assigned to her? (Photo from Open Dialogue)

Social conditioning

There are many levels of bigotry – being this racism, homophobia, transphobia or any other kind of aversion felt towards minority groups. The phobia can be conscious, deliberate and hateful, or it can be implicit and an indirect effect of cultural prejudices.

One of the ways society keep marginalized groups excluded is by conditioning its citizens to fear or loathe them. This is not only a mental process; it is an emotional form of conditioning.

Kids will, from a very young age, see that their parents and peers express distaste when meeting – or talking about – members of these groups.

The same adults will often use the same kind of expressions as when they talk about something diseased, rotten or corrupt. Kids pick up on these feelings. They develop the same emotional responses.

Bigoted narratives reinforce the phobias

This process is of course accentuated by the way the bigots present the children with narratives aimed at legitimizing this aversion.

We have all heard these stories: "The Jews are part of a world-wide cabal aimed at ravaging white women, sacrificing or kids and turning us all into Communists," or "Black people are primitive, lazy, violent and promiscuous animal-like beings who threaten white women and kids," or "Gay people are grooming good kids to become queer pedophiles."

Fascist propaganda is actually very much about presenting outsiders as a sexual threat to predominantly white women and kids. This tactic legitimizes policies aimed at oppressing those marginalized, and this oppression in turn creates more distrust and disgust.

This is the tactic the Republican party is using against LGBTQA people and immigrants in the US right now, and is a strategy exploited by the so-called "gender critical" TERFs of Britain.

Freeing yourself from phobias

Note that it can be hard to overcome such feelings of loathing and fear, since they are based on long term reinforcement. This means that someone who intellectually have understood the nature of transphobia or racism, and who consciously supports trans rights or the civil rights movement, may still harbor bigoted feelings.

Indeed, getting rid of such feelings may take time. It often requires regular contact with members of the marginalized group, so that your subconscious come to see them as regular people and not as some kind of scary "Other".

So a woman who – because she has been raised in a racist or transphobic environment – feel unease about being cared for by a Black or transgender woman, may on one level be an anti-racist or trans-supportive person, but may – nonetheless – express racist or transphobic feelings. Because of this she continues to reinforce the negative biases of this world.

Is she a bad person? I wouldn't say so. But it would definitely help if someone helped her out of that state of mind.

Experienced as invalidating aggression

Dismissing a Black gynecologist because she is Black or a transgender doctor because she is trans, will definitely be experienced as a bigoted reaction. The caretaker will experience this as aggression aimed at invalidating her status as an equal human being.

Now, the question posed is a bit confusing, as it is referring to the female doctor being "a pre-transition trans woman". A trans female caretaker who works as a woman will have already come out. She has transitioned, at least socially. She presents as a woman. She is a woman.

I know of no one who allows closeted trans women (i.e. those who publicly still present as men) to work as female doctors.

It might be the expression is not referring to this trans woman having socially transitioned. Instead the question might be alluding to whether she has been through hormone replacement therapy and surgery, so that she easily passes for a cis woman.

But that brings us back to the social conditioning: The unease someone feels from facing a woman who is visibly trans (or meeting a female doctor who is clearly a woman of color) is caused by a transphobic or racist culture that teaches us that transgender or Black women are dangerous, contaminated or inferior. That is clearly a transphobic or racist reaction, even if the patient's conscious intentions are good.

We cannot win the battle against bigotry if we continue to insist on keeping the marginalized groups segregated from "normal" society due to the misguided fears of prejudiced people. That segregation is in itself one of the instruments used to keep the oppressive system in place. This applies to bathrooms, participation in sports, as well as gynecology.

#transgender#trans#gynecology#racism#black doctors#transgender doctors#bigotry#homophobia#lgbt#lgbtqa#lgbt+#queer

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why There Are So Many Black Women Dying When Pregnant Or Giving Birth

And why nothing is being done to stop it!

Black women in the U.S. are nearly three times more likely to die during pregnancy or delivery than any other race.

This report reflects on the medical racism, bias, and inattentive care that Black Americans endure. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, black women have the highest maternal mortality rate in the United States — 69.9 per 100,000 live births for 2021, almost three times the speed for white women.

Black babies are more likely to die and far more likely to be born prematurely, setting the stage for health issues that could follow them through their lives.

Black patients lead preterm births.

African American children are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to be born prematurely, which can lead to developmental and other health issues.

To be Black anywhere in America is to experience higher rates of chronic ailments like asthma, diabetes, high blood pressure, Alzheimer's, and, most recently, COVID-19. Black Americans have less access to adequate medical care; their life expectancy is shorter.

From birth to death, regardless of wealth or social standing, they are far more likely to get sick and die from common ailments.

From birth to death, regardless of wealth or social standing, they are far more likely to get sick and die from common ailments.

Black Americans’ health issues have long been ascribed to genetics or behavior when various circumstances linked to racism — including restrictions on where people could live and historical lack of access to care — play significant roles.

Discrimination and bias in hospital settings have been disastrous.

The nation’s health disparities have had a tragic impact: Over the past two decades, the higher mortality rate among Black Americans resulted in 1.6 million excess deaths compared to white Americans.

That higher mortality rate resulted in a cumulative loss of more than 80 million years of life due to people dying young and billions of dollars in health care and lost opportunity.

A yearlong Associated Press project found that Black Americans' health challenges often begin before their first breath.

The AP conducted dozens of interviews with doctors, medical professionals, advocates, historians, and researchers who detailed how a history of racism that began during the foundational years of America led to the disparities seen today.

The report is Part 1 and will be followed up with additional 'series' informational reports from the Associated Press. Because of this report's in-depth, objective, and original reporting, b&s invites you to visit the initial information by clicking here.

Please pass this on to others who may benefit from its references, and for readers wanting to know, as the other series from the Associated Press is published, there will be every effort made to pass it on to you.

Again, to read about this urgent concern that affects everyone, especially those in our Black Communities, please read Part One of a continuing series from the AP here.

#aclu#black lives matter#black lgbt#black stories#cnn#lgbtqi#arizona#lesbian#gay#lgbt#black history#black love#black man#blacklivesmatter#black history month#black doctors#black physicians#black women#black woman#beautiful black women#ebonybeauty#blackgirlmagic#blackisbeautiful#black culture#black pregnant#naacp#black health#black liberation#black lives are beautiful#black lives have value

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Born in Trinidad, Dr. John Alcindor earned his MD in Scotland in 1899 & was a physician, political activist, & senior district medical officer in London. He was awarded a Red Cross medal for his work treating the wounded in WWI. His great-nephew is Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black owned#black owned business#black owned businesses#black business#black entrepreneurs#black excellence#support black owned#business owner#entrepreneur#black economics#medical#black medicine#black doctors#tiktok

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

The fatal shooting of Dr. Preston Phillips, one of the four people killed this week during a shooting at St. Francis Hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Dr.Phillips was more than just a doctor, he was a man who cared deeply about his community.

12 notes

·

View notes