#bertran de born

Text

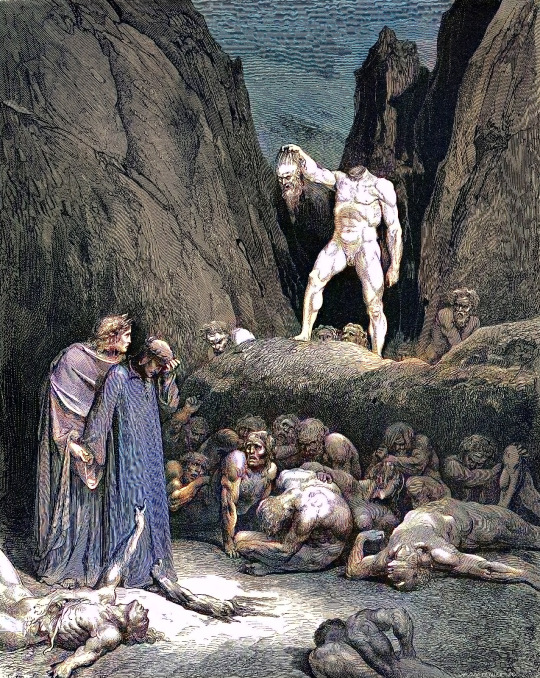

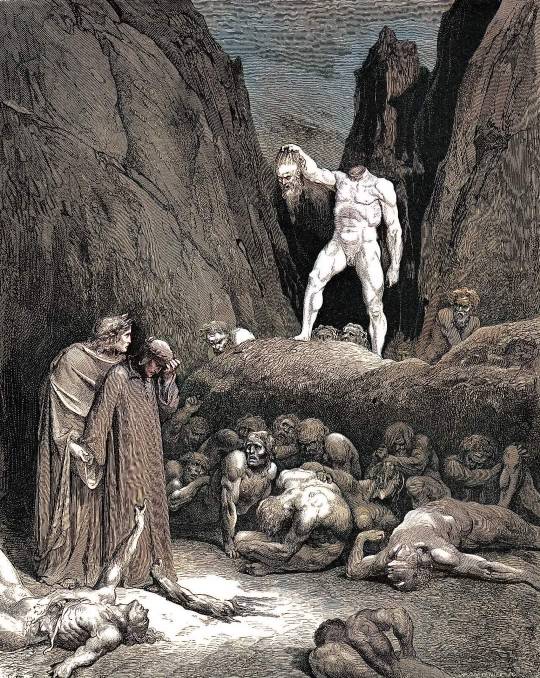

Inferno Canto 28, Bertran de Born Holding His Severed Head - Gustave Doré, 1866.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bertran de Born from Dante's Inferno, Canto 28, illustrated by Gustave Doré

Dante shields his face from the horrifying appearance of Bertran de Born, who allegedly fermented the rebellion between Henry III and his father, King Henry II. His brain has been severed from his body even as he severed the relationship between father and son. The engraver, Auguste Pontenier (1820-1888), has placed his signature at the bottom right, while the artist Gustave Doré (1832-1888) has placed his signature at the bottom left.

#bertran de born#dante alighieri#virgil#inferno#art#hell#the divine comedy#divine comedy#gustave doré#auguste pontenier#illustration#history#europe#european#medieval#middle ages#renaissance#troubadour

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

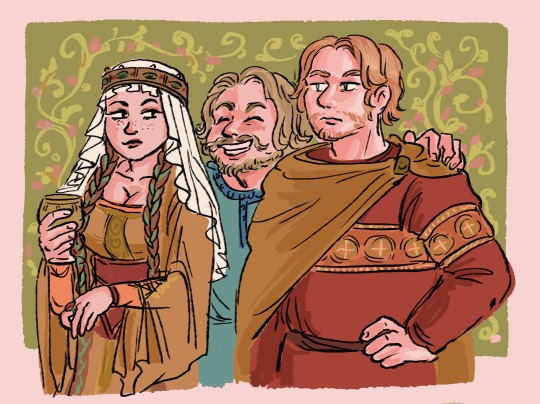

Matilda of Saxony/Bertran de Born/Count Richard

“I wish that Lady loved me, and the Lord of Poitou loved me too!”

#Idk if the quote is real but I like to imagine.#this is in his head btw. He’s not getting laid RIP#Bertran de born#troubadour sandwich#Richard the lionheart#Matilda of Saxony#angevins#12th century#medieval#my art#happy new year!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe Auguste

The Capetian monarchy was an institution, with traditions and restrictions. But the personal element in the medieval period always remained a significant factor. To what extent the government of any individual king was personal is not easy to determine. In general it is true that counsellors could advise, but could not normally decide policy. Others were there to obey the will of the monarch, perhaps to help form it, but not to take over from it. Philip's views were shaped by many influences: by observing his father's work, by his father's advice, by his own education, by the advice he received from counsellors, by the experience of governing, by the views of churchmen, theologians, popes and fellow rulers, but in the end they were his views and could be imposed to the extent of the power of the monarchy at the time. Philip's court and government reflected his own personality. Gerald of Wales pointed out its contrasts with the Plantagenet court, the French king's being more sober as we have seen, more quiet in tone, more proper, with swearing forbidden. Philip brought about significant changes: less reliance on the magnates, a lesser role for his family; a greater place for the selected dose counsellors and for relatively humble knights.

It has been suggested that Philip's intellectual gifts were 'modest', which, although direct evidence is not easily available, seems to conflict with what we know about the king's abilities. He was able to deal with the bright men around him, such as Peter the Chanter. He was able to supervise governmental development and the administration, which needed a considerable grasp of accounting as well as a degree of literacy. His ability to deal with the papacy reveals a clear understanding of legal argument and his rights, and a firm determination to protect them. He was rarely outmanoeuvred by even the cleverest of his opponents. Philip went to war as any leader of his period would, but he was more prepared than most to seek and make peace.

Rigord said that Philip's aim was 'to deliver the weak from the tyranny of the strong', and that 'his first triumph is to see peace re-established'. His tolerance and mild temper puzzled the aggressive Bertran de Born, who thought the French needed a leader and had not found one in Philip, who did not become angry. Bertran preferred the attitude of Richard the Lionheart, for whom 'peace and truce have never been noble'. For Bertran it was a sneer to suggest that Philip liked peace even more than the noted diplomat Archbishop Peter of Tarentais. Bertran had cause to regret his underestimation of Philip, when the king later used his authority to replace Bertran as lord of Hautefort. No doubt that act was executed on the advice of counsellors, and Bertran could further nurse his belief that Philip was 'badly advised and worse guided'.

Philip did in fact at times lose his temper, but usually with some point, as when he chopped down the elm on the Norman border, declaring by actions rather than words that he no longer accepted the Plantagenet stance on their rights to bring the king to the edge of their territories before they would hold discussions. Nor were his diplomatic activities always appreciated by his enemies. He could manoeuvre and manipulate with the best of them; he was the 'sower of discord' according to one English chronicler. To take just one example of his methods: in the conquest of Normandy he knew that Rouen was the key, which afterwards he would need to govern. Therefore he did not simply crush Rouen, and chose to discuss with the leading citizens what they would gain from surrender. If allowed in, he promised: 'I will prove a kind and just master to you.' In modern times he has been called 'a statesman of the first water', 'the first royal statesman in French history' ; it is a reputation which in this country we have somehow failed to recognize.

[..]

Philip was generally modest and unassuming, as we have seen in contrast to Richard the Lionheart both in Sicily and in the Holy Land. Bertran de Born thought the French king presented his deeds in tin-plate rather than in gilt. But Philip was aware of the need to present a regal figure, dignified if not flamboyant: a public face of modesty but a recognition of his own powers. The scene painted by Mouskes of Philip entering a church and praying: 'I am but a man, as you are, but I am king of France', has a deep truth to it. There is also a story of Peter the Chanter telling Philip what were the attributes of an ideal sovereign; Philip replied that he should be contented with the king that he had.

The efforts to show his connection back to Charlemagne demonstrate Philip's effort to bolster the Capetian position. His mother, Adela, and his first wife, Isabella of Hainault, both claimed descent from Charlemagne. His natural son was named Peter Charlot, after the great emperor. And the Carolingian claim seems to have become generally accepted. Innocent III declared: 'it is common knowledge that the king of France is descended from the lineage of Charlemagne'. No doubt there was some weakness in the argument, but William the Breton refers to him as 'the descendant of Charlemagne', and the Welshman Gerald believed that Philip aimed to restore the monarchy to 'the greatness which it had in the time of Charlemagne'.

Philip wished to present an imperial image of French monarchy, hence the use of an eagle on his seal, the label 'Augustus' applied by Rigord, his sister's marriage to two Byzantine emperors, and the raising to the Latin imperial throne of two of his brothers-in-law. The same point was being emphasized when the sword of Charlemagne had been brandished at Philip' s coronation ceremony. As one of the Parisian masters wrote in 1210: 'the king is emperor in his realm'. The royal family was being distanced from other families, however noble; royal power was being set above noble power. It was not just a question of wealth and lands, but of the nature of monarchy, its prestige, its religious and mystical significance. The claimed association with Charlemagne, by the twelfth century a powerful figure in legend as well as a great historical emperor, was an important part of this process.

Philip was a tough-minded individual, he would not otherwise have been such a great king. Those who had experience of dealings with Louis VII found Philip a much harder opponent with more steel in his character. He had tremendous determination, and strong views on basic policies. Before his father's death, while still a teenager, Philip was prepared to rule, issuing charters without his father's consent, reacting against some of his father's policies. Before long he threw off the shackles of his mother and her powerful family, and soon afterwards of the count of Flanders. The English chronicler Howden thought he did it because he 'despised and hated all whom he knew to be familiar friends of his father', which seems a distortion, but at least underlines the point that Philip was of independent mind from the first.

Philip preferred his close counsellors to be lesser men who accepted their subordinate role without question. We may be clear that his policy expressed his own views. There was an encounter at one of the conferences between Philip and King John which occurred between Boutavent and Gaillon, when the two kings were 'face to face for an hour, no one except themselves being within hearing', a brief comment but one which allows a sudden and vivid insight into the personal nature of thirteenth-century diplomacy.

Of course Philip took counsel, and made a point of doing so, but he was too independent a man to be dominated by another. And though inclined to prefer diplomatic solutions, he was a good enough warrior to win respect; as William the Breton said 'his arm was powerful in the use of weapons'. Bouvines was the most important battle of the age, and Philip was the victor. Where the loss of documentary evidence from the earlier period often makes it impossible to be certain that Philip was the innovator or the initiator, a knowledge of his character, his able leadership and his drive, make him far and away the likeliest candidate. One of Philip's major achievements was to shift the balances of an intricate system of government in France in favour of the Capetian monarchy, so that its views were more often heeded, and came to be heeded in areas where that had not previously been the case.

Jim Bradbury- Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223xiii

#xii#xiii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#philippe ii#philippe auguste#pierre le chantre#rigord#bertran de born#richard coeur de lion#adèle de champagne#isabelle de hainaut#agnès de france#jean sans terre#battle of bouvines

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bertran de Born - Ensenhas -

Pois als baros

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i'm not putting this in the main tag. lol. lmao#i remember joking with strawberry in their tdd stream about how daniel needs no juice to essentially become a harvester#shoutout to the 10-13th c. upper military class for easily beating him out tho in being Absolute Fucking Freaks™ 👍#(although Bertran de Born is bit notorious in general for being on the extreme end of that spectrum to be fair)#The Poems of the Troubadour Betran de Born ed. Paden Jr.‚ Sankovitch‚ and Stäblein

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inferno Canto 28, Bertran de Born Holding His Severed Head - Gustave Doré, 1866.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

When battle is joined, no noble knight thinks of anything other than breaking heads and arms.

Bertran de Born, Baron and troubadour (c. 1140-1215)

1 note

·

View note

Text

“…We have to start not with tactics or the physics of shouting orders, but with cultural expectations. First, we need to establish some foundations here. First, in a pre-modern battle (arguably in any battle) morale is the most critical element of the battle; battles are not won by killing all of the enemies, but by making the enemies run away. They are thus won and lost in the minds of the soldiers (whose minds are, of course, heavily influenced by the likelihood that they will be killed or the battle lost, which is why all of the tactics still matter).

Second, and we’ve actually discussed this before, it is important to remember that the average soldier in the army likely has no idea if the plan of battle is good or not or even if the battle is going well or not; he cannot see those things because his vision is likely blocked by all of his fellow soldiers all around him and because (as discussed last time) the battlefield is so large that even with unobstructed vision it would be hard to get a sense of it.

So instead of assessing a battle plan – which they cannot observe – soldiers tend to assess battle commanders. And they are going to assess commanders not against abstract first principles (nor can they just check their character sheet to see how many ‘stars’ they have next to ‘command’), but against their idea of what a ‘good general’ looks like.

And that idea is – as we’re about to demonstrate – going to be pretty dependent on their culture because different cultures import very different assumptions about war. As I noted back in the Helm’s Deep series, “an American general who slaughtered a goat in front of his army before battle would not reassure his men; a Greek general who failed to do so might well panic them.” An extreme example to be sure, but not an absurd one. In essence then, a general who does the things his culture expects from him is effectively performing leadership as we’ve defined it above.

But the inverse of this expectation held by the soldiers is that generals are not generally free to command however they’d like, even if they wanted to (though of course most generals are going to have the same culturally embedded sense of what good generalship as as their soldiers). Precisely because a general knows his soldiers are watching him for signs that he is their idea of a ‘good general,’ the general is under pressure to perform generalship, whatever that may look like in this cultural context.

That is going to be particularly true because almost all of the common models of generalship demand that the general be conspicuous, be available to be seen and observed by his soldiers. As a result, cultural ideals are going to heavily constrain what the general can do on the battlefield, especially if they demand that the general engage personally in combat.

We can actually get a sense of a good part of the range simply by detailing the different expectations for generalship in ancient Greek, Macedonian and Roman societies and how they evolved (which has the added benefit of sticking within my area of expertise!).

On one end, we have what we might call the ‘warrior-hero general.’ This is, for instance, the style of leadership that shows up in Homer (particularly in the Iliad), but this model is common more broadly. For Homer, the leaders were among the promachoi – ‘fore-fighters,’ who fought in the front ranks or even beyond them, skirmishing with the enemy in the space between their formations (which makes more sense, spatially, if you imagine Homeric armies mostly engaging in longer range missile exchanges in pitched battle like many ‘first system‘ armies).

The idea here is not (as with the heroes of Homer) that the warrior-hero general simply defeats the army on his own, but rather that he is motivating his soldiers by his own conspicuous bravery, ‘leading by example.’ This kind of leadership, of course, isn’t limited to just Homer; you may recall Bertran de Born praising it as well:

And I am as well pleased by a lord

when he is first in the attack,

armed, upon his horse, unafraid,

so he makes his men take heart

by his own brave lordliness.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, there is the pure ‘general as commander’ ideal, where the commanding general (who may have subordinates, of course, who may even in later armies have ‘general’ in the name of their rank) is expected to stay well clear of the actual fighting and instead be a coordinating figure. This style, for reasons that we’ll get to a little later in this post, is fairly rare in the pre-gunpowder era, but becomes common afterwards.

Because in this model the general’s role is seen primarily in terms of coordinating various independently maneuvering elements of an army; a general that is ‘stuck in’ personally cannot do this effectively. And it may seem strange, but violating these norms with excessive bravery can provoke a negative response in the army; confederate general Robert E. Lee attempted to advance with an attack by the Texas Brigade at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 6, 1864) only to have his own soldiers refuse to advance until he retired to a more protected position.

Of course this sort of pure coordination model is common in tactical video games which only infrequently put the player-as-general on the battlefield (or even if the ‘general’ of the army is represented on the battlefield, the survival of that figure is in no way connected to the player’s ability to coordinate the army).

In practice, pre-modern (which is to say, pre-gunpowder) generals almost never adopt this pure coordination model of generalship. The issue here is that effective control of a gunpowder army both demands and allows for a lot more coordination. Because units are not in melee contact, engagements are less decisive (units advance, receive fire, break, fall back and then often reform to advance again; by contrast a formation defeated in a shock engagement tends not to reform because it is chased by the troops that defeated it), giving more space for units to maneuver in substantially longer battles.

Moreover, units under fire can maneuver, whereas units in shock generally cannot, which is to say that a formation receiving musket or artillery fire can still be controlled and moved about the field, but a unit receiving sword strikes is largely beyond effective command except for ‘retreat!’

…What I want to note here is that these expectations are going to impact where the general is on the battlefield and thus what he can do to exert command. A general in a culture which expects its leaders to be at the front leading the army has the advantage of being seen by at least some of his soldiers (indeed that is the point – they need to see him performing heroic leadership), but once engaged, he cannot go anywhere or command anyone.

This is also true, by the by, in cultures where the general is expected to be on foot to show that they share in the difficulties and dangers of the infantry; this is fairly rare but for much of the Archaic and Classical periods, this was expected of Greek generals. Even if a general on foot isn’t in combat directly, their ability to see or move about the battlefield is going to be extremely limited.

On the flipside, a general who is following the ‘commander’ ideal is likely to be in the rear, perhaps in an elevated position for observation. The obvious limitation here is that such a commander is going to struggle to display leadership because no one can see them (everyone is facing towards the enemy, after all).

But that also impacts their ability to command – no one is looking at them so if they want to change their plans on the fly they need to send word somehow to subordinate officers who are with or in front of the battle line who can then use their visibility to communicate those orders to the troops.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Commanding Pre-Modern Armies, Part II: Commands.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A memory that I replay to myself...

A stage-actor, I work up a feverish tempo... crying... my audience is led down the depths of the dry well of sorrows...

Suddenly, the actor breaks character and start laughing, nearly on a level of sadism... "LOL! This is the only way I can get myself to cry... Isn't that funny? Isn't that fucked up?"

youtube

The assumption that "a normal person would not feel what I feel" and "if a person feels what I feel, then they are not normal, in fact they are pathological... by my adopted standard of definition."

I feel like I have practiced and trained myself to laugh and cry on command... express emotion, express pathos.... "express your inner goo".

So I was just crying out of genuine sorrow, but then the-other-thought-process started thinking of fucked-up jokes, fucked up self-smirches, so I'm sobbing and laughing like a maniac in rapid cycle. It feels exhausting.

Sorry, I love reframing myself as a freak. I love to dissect myself from context to become a freak. Even in the story, that's exactly what's happening...

what's a sculpture? Something shaped through the removal of matter...

It takes 30 years for a tree to grow this tall and strong, but in five days you could reduce it to rubble. -- a mockery.

"but It's easy to criticize,

and it's easier to laugh than cry...

and it's easy to do it all again...

but I don't know what to say to make you see the sun --- the same Sun...

--shining down on me: all right..

--shining down on you: all wrong

lyrics of Something..

"Give a man a mask, and he will show you who he really is..."

...Do you think that to be true, Mr. Will Graham?

After all, they say that the key to intelligent tinkering is to save all the pieces... nevermind all the lifeless organs lying on the tray.

Can I bring it back to life?

Okay, fine, when I'm cutting open your spleen, I'll make sure you're alive and feeling... I'm saving the pieces. I take your constructive criticism.

The relativity of the situation demands it.

WHERE TO, NEXT?

There's another story I heard...

Let’s go back to Bertran de Born.

Why was his head cut off?

Because he was a schismatic, he set people up against their loved ones. Bertran divided people and now he himself is divided, literally. Bertran embodies his punishment. And this goes for all the sinners who we have met. But the contrapasso is not a simple punishment for making a mistake. The sinners chose to live their lives in the wrong way: they did the wrong things for the wrong reasons. And ultimately this has a consequence, such behavior takes you to the wrong place: inferno. The contrapasso is then really not an punishment by an external judge, a vengeful God. Rather it is the revelation of an inner spiritual condition. After a life of self-creation the inner state of the sinful soul is now externalized into an eternal exemplar.

youtube

"The boy in the belfry, he's crazy

--- throwing himself down from the top of the tower.

Like a hunchback in heaven, he's been ringing the bells of the church for the last half an hour...

and he sounds like he's missing something-or-someone that he knows he can't have... now..

and if he isn't, I certainly am.

I just ask what it means if this sort of emotional-surgery leaves behind scars all the same as a bodily-surgery

(unless the right techniques are employed; unless tension is relieved).

What if the condition of the self-immolator is a revelation of someone who has been doing this to their own mind during their life?

(and if he isn't, I am.)

Is the physical condition a consequence of the spiritual condition?

....to live, covered in scar-tissue and the grafted skin of other people. It hurts. Does it, now?

Are you just crying for sympathy, after the fact?

youtube

0 notes

Text

Inferno XXVIII

Impegni rispettati. La giornata si chiude mentre rimugino sul XXVIII canto. Qui entrano in gioco i servi più fedeli del male.. coloro che 'dividono'.

Dia-ballein.. "mettersi in mezzo".. Seperare... l'uomo da Dio, gli uomini fra loro, la vita di noi tutti tra desideri bassi e aspirazioni alte...

Due punti:

1) le ferite, i corpi straziati.. ribaltamento dell'iconografia dei martiri cristiani... lì dove sono segno di Testimonianza.. un indicare una 'Vetta' per la quale si può sopportare di tutto.. qui in questa bolgia diventano punizione eterna.. il tempo di guarire e nuovamente viene straziato, senza alcun senso. Un dolore per il dolore.

2) la vicenda di Bertran de Born.. la testa mozzata.. la testa lontana dal cuore.. la seperazione - ancora! - fra pensiero e cuore... ."ed erano due in uno e uno in due". L'Unità è andata. LA divisione per eccellenza.. quella NELLA persona: i risultati? Discordia e lotta, in sé e fuori. Nella società.

.

0 notes

Text

Philip II Augustus, or as described in someone's tags, one of the "top 10 most punchable historical figures. Unfortunately. He is also extremely entertaining."

Philip was the first to style himself King of France rather than King of the Franks. he is known for his role in the Third Crusade and tumultuous relationships and manouvers against Henry II, Richard I, and John I of England, eventually resulting in regaining the Angevin Empire's territories in France. Bertran de Born early on derided some of his political and military decisions as being cowardly in some contemporary poems (a "lamb" against Richard's "lion"). However, later writings described him as being "more cunning than a fox," and as one who loved to "provoke discord" amongst men who resisted him. He also seems to have done a lot of things that have been puzzling for some historians, such as

While an notable figure in French history obviously, in my perusals he seems to rarely ever pop up in mainstream recent anglophone media as a major character, but when he does at all it seems like it's to have toxic gay drama with Richard. This is mostly not very historical and based on dated early 20th century scholarship, but has made for some very iconic entertainment that, in spirit at least, seems consistent with the legacy of Being A Dramatic Bitch

#Philip Augustus#Philippe Auguste#Philip II of France#Additional notes:#Most of my reading has been jean flori and Strickland#And flori is. Very funny. Very dramatic even when he is not trying to#He's just constantly like *scratches head* So Philip did XYZ. We don't know why and it doesn't make sense#But he sure did that behavior#Debunked yaoi but th#No respect for monarchs but I will fujofy their toxic traits. Sorry not sorry#12th century#French history#Fanart#Medieval#Capetians#Unrelated but I started drawing him brunette just bc like#Most of the modern art portrayals run with that#And it just feels consistent to me lmao in my brain#He's bald anyway in his later life so it doesn't matter#Bald Philippe representation#My art

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

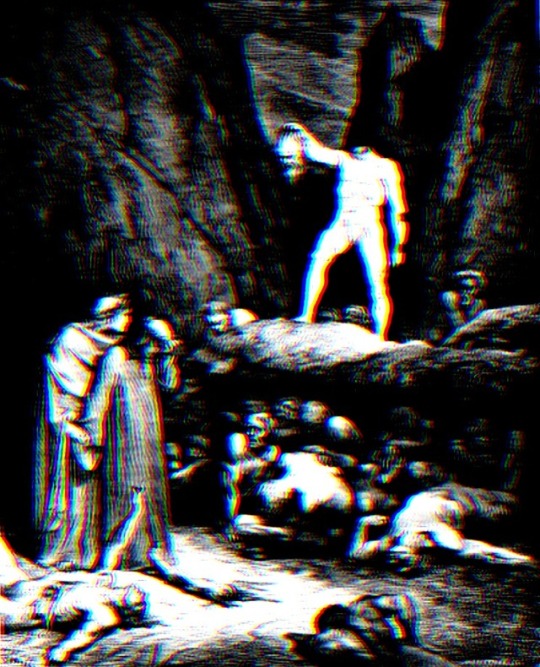

Gustave Dorè’s illustration of Divine Comedy, Inferno Canto XVIII, Bertran De Born

#gustave dore#divine comedy#dante alighieri#virgil#bertran de born#mutilation#suffering#inferno#dante's inferno#canto xviii#àcreepy#horror#rgb effect#aesthetic#art#illustration

201 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bertran de Born (1140-1215) - Ai, Lemosins, Francha Térra Cortesa

Eduardo Paniagua

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Perseus with his fistful of belladonna

could we transform him into a hermit

with a lantern? Give him an awl,

teach him meander-work, zigzag wobbling through

the infante-clotted rushes, teach him salamander,

teach his semen how to stimulate fire. Unblock

the entrance way to Hades, allow the violet odors

of its meats to simmer in ice penetrating

advice. Something will work its magic against

the door of never.

Clayton Eshleman, “Hades in Manganese” in Juniper Fuse

#this psg seems like the answer to kenneth gross' reading of perseus w the head of medusa that i posted here the other day#but i also love how eshleman fuses (lol) the tarot hermit with bertran de born holding his own head like a lantern....#clayton eshleman

0 notes

Photo

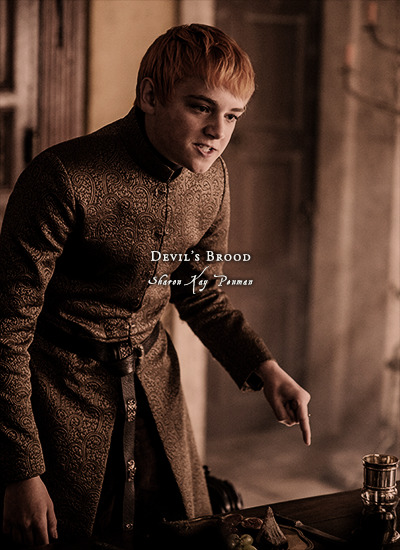

Favorite Historical Fiction || Devil’s Brood by Sharon Kay Penman ★★★★☆

Richard’s eyes narrowed. “A pity you were not born a woman in this life, Little King of Lesser Land, for you seek only to please and to be admired by all. You’d have made a right fine whore.”

Tilda gasped. She did not understand why he’d called Hal “Little King of Lesser Land,” although she recognized it as a grave insult. Geoffrey did understand and bit back a grin; Richard was quoting from a song by the troubadour Bertran de Bòrn, who’d mocked Hal for not displaying more martial fervor.

Hal flushed, but he lashed back at once, saying with all the contempt at his command, “And a pity you were not lowborn in this life, that the blood of kings keeps you from following your heart’s desire. You are never happier than when you are up to your knees in blood and guts and gore. Clearly the Almighty meant you to be a butcher.”

Hal knew his retort had missed its mark as soon as the words left his mouth, even before Richard laughed at him. “When men fight, they bleed and sometimes they die, for war is not as pretty or fanciful as your tourney games. War is real, so little wonder you like it not.”

“Rot in Hell!” Hal spat, but Geoffrey decided to intercede before things got totally out of hand, and interrupted Hal in mid-curse.

#bookedit#litedit#devil's brood#sharon kay penman#medieval#historical fiction#books#hf edits#nanshe's graphics

30 notes

·

View notes