#bön

Text

Att bönen möter tystnad är hon van vid, men var och en som tror lär sig ana skillnad i tystnadens art. Nu, för första gången i sitt liv, känner hon tystnaden från den gud som har vänt henne ryggen: en som tröttnat på denna åldrande kvinna och de trångmål i vilka hon försatt sig av egen dårskap.

Ödet och hoppet, Niklas Natt och Dag

0 notes

Text

Meditation

Defintion

Handlingen att ge din uppmärksamhet åt endast en sak, antingen som en religiös aktivitet eller som ett sätt att bli lugn och avslappnad.

Efter år av meditering har jag kommit att förstå att meditering är att tillåta vad som är. Det är att sätta sig ner, sluta sina ögon, lägga märke till andningen, ljuden runt om en, tyngden av kroppen och rummets temperatur. Att meditera. Att ge upp…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

BÖN

“Bön bön bakmak” diye bir tabir var. Oysa sadece bön denildiği zaman bir şey anlamayabilir hatta Fransızca bile sanabilirsiniz. Bir dil uzmanı olmamakla birlikte çok iyi Türkçe kullanan biri de olmamama rağmen taa Orta Asya’dan günümüze kadar dilimiz konusunda çok acayip bir değişim içersinde olmuşuz olmaya da devam ediyoruz.

Orta Asya kökenli Türk toplumlarının günümüzde kullandığı dile…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

bu evde tezgaha çıkmak yasak ulan!

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

highly recommend listening to one song on repeat for hours on end while staring blankly at a light projector

autism brain happy

#the song is karolinens bön by sabaton btw#yes yes yes#more of that stuff please says my brain#words from my head

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oradan tır geçer diyenlerin üzerinden tırla geçmek istiyorum

#duvarla ve tırla aramda birkaç cm var#en ufak yanlış harekette arabayı çizebilirim#utanmadan şöförlüğümü sorgulamaya kalkıyor#gel tırla buradan geç bakalım dediğimde bön bön bakması#hepiniz iyi şoförsünüz ben değilim tamam size bir şey ispatlamak zorunda değilim#siz derken sizi kastetmiyorum dostlarım

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today, the incredible pictographic Dongba script is nearly extinct. However, realising the wrongs of the past, the Chinese government has been trying to revive it in an attempt to preserve the remarkable Naxi culture.

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tenshō Daijin: the many guises of medieval Amaterasu (part 1)

I’ve been working on this article on and off since late 2021, and it’s the longest one I’ve published on my blog so far (some of my wikipedia contributions are bigger, but that’s a separate matter). In fact, it's so long I have to split it into two due to limitations of tumblr's post editor.

When most people speak of “Japanese mythology”, 99% of the time they effectively think just of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki (with some night parade scrolls sprinkled in, maybe, even though that’s not really mythology, but Edo period popular entertainment). The goal of this article is to challenge this incorrect view, and to shed some light on the mythology of the Japanese “middle ages” - roughly between the 11th and the 16th centuries.

I decided to use Amaterasu as the main topic, as it’s hard to think of a better way to showcase how much mythology remains outside the general perception than using a figure who, at least at first glance, is well known as an example. From Brahma longing for a friend to Yang Guifei surviving own death, I’m sure everyone will find something new here.

Myths obviously aren’t all that will be covered here, though. I’ll also discuss the theological doctrines which flourished in the middle ages, with a particular emphasis on honji suijaku, their social context, and more. You will be able to find out what rituals focused on Amaterasu had to do with Enma and Taizan Fukun, how economic woes of the Outer Shrine of Ise impacted Brahma’s role in Japan, why some secrets existed only to be deliberately revealed, and more.

Kami and Buddhism

In order to discuss the development of Amaterasu’s character and her associations with other figures through the middle ages, as well as the myths which developed as a result, I’ll first need to summarize the nature of interactions between kami and Buddhism through the Nara, Heian and medieval periods. I’m specifically saying kami, as opposed to Shinto, for reasons which will become clear later.

It seems that at first the relation was rather standard as far as early interactions between Buddhism and preexisting religious traditions in areas where it was introduced go. Mark Teeuwen singles out Tibet and various kingdoms corresponding to parts of present day Myanmar as examples particularly similar, though obviously not identical, to early Japan. The parallel developments concerned the Bön faith in the former and the beliefs pertaining to the nat in the latter.

The early sources appear to indicate that kami were envisioned as beings who need to strive towards enlightenment themselves. Recitation of sutras was described as a way to bring them closer to that state. However, some rather quickly started to be viewed as active protectors of Buddhism. As early as 741 Hachiman was already regarded as such, for instance. Additionally, combinative “shrine-temples” already existed in the same period too, attesting to a fusion of Buddhism and preexisting tradition.

A schematic representation of some examples of the honji suijaku from the Kasuga mandala (wikimedia commons)

A breakthrough occurred in the ninth century, with the development of honji suijaku (本地垂迹) - the theory on kami being “traces” or “emanations” (suijaku) of Buddhist figures, referred to as “original sources” (honji). Similar theories regarding Daoist figures were at times advanced by Chinese Buddhist scholars as early as in the fifth century, so it was hardly an unparalleled development, though its scope was fairly unique. By the end of the Heian period, honji suijaku became the default mode of understanding kami.

A common misunderstanding today is that honji suijaku meant exact correspondence between a single Buddha and a single kami. In reality, what it created is a “fluid pantheon”, to borrow the title of one of Bernard Faure’s books dealing with this phenomenon. Connections between specific kami and Buddhas (or bodhisattvas) certainly were often established. However, that was not all.

Kami could be connected to other kami, and Buddhas to other Buddhas; and on top of that both groups belonged to an elaborate network which also included devas, wisdom kings, astral deities, legendary heroes and historical figures from various countries (for example Daoist immortals), and beings which defy classification altogether. In Keiran Shūyōshū (溪嵐拾葉集), the notion of honji suijaku is even extended to silkworms (their honji is Aśvaghoṣa). Multiple identifications could coexist, sometimes in the same sources. On top of that, individual figures could change classification depending on context.

The new theological ideas also lead to the formation of new myths, collectively referred to as chūsei shinwa (中世神話; “medieval mythology”). As summarized by Sujung Kim, this term encompasses both the myths which arose in the Japanese “middle ages”, the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1185-1600), and modern study of them. A closely related, though more narrow, term is chūsei nihongi (中世日本紀), which refers specifically to reinterpretations of preexisting classical myths, for example Nihon Shoki, from the same times.

One of the primary goals of the new myths was to create a metaphorical bridge between Japan and the lands described in Buddhist literature transmitted from China, Korea and beyond. Sutras and other literature were often set in fabulous distant kingdoms or in supernatural realms. At the same time, the material reality of Buddhism tied it to local institutions and landscape. As a result, the local was imbued with a new, universal meaning.

As Mark Teeuwen put it in his article The Buddhist Roots of Japanese Nativism, medieval literature “allowed a local warlord to pose as a golden cakravartin, a local mountain to take on the guise of the cosmic Mt. Sumeru, a local deity to embody an aspect of the World Buddha, and a local rite to aspire to the universal aim of bringing salvation to all sentient beings.” At the same time, the universal gained a local dimension, making it easier to grasp and more approachable.

However, that was hardly the end, more like the beginning - yet another prominent change which occurred over the course of the 12th and 13th centuries resulted in the formation of a new belief: select kami were in fact not emanations of secondary importance of Buddhist figures, but direct representations of enlightenment. These developments eventually culminated in what is sometimes described as “reverse honji suijaku”: Buddhas and bodhisattvas were merely manifestations of primordial kami, not the other way around.

The motivations behind the development of these ideas are not clear. While especially in the past it was commonly assumed that they represented the beginning of a “pristinely Japanese” spirituality reasserting itself against “foreign” Buddhism, most of the theologians involved were Buddhists themselves, or at least enthusiastically drew inspiration from Buddhist sources. Mark Teeuwen and Fabio Rambelli suggest they might have been motivated by a desire to take Buddhist theology to logical extremes in order to investigate the nature of reality before the emergence of the first Buddha and the current kalpa.

Furthermore, in addition to lofty theological speculation material motivations might have been at play. Many of the advocates of reverse honji suijaku might have been so-called “shrine monks”, tasked with maintaining the shrine parts of religious complexes. Possibly their need for broader recognition and greater authority made them keen on such theological reversals. This is ultimately speculative, though.

Curiously, reverse honji suijaku arguably might have led to the creation of Shinto in the modern sense. While the phrase 神道 has a long history, and it is applied to intellectual and religious movements active in the middle ages in modern literature (for example, the treatises of a certain priestly family I’ll discuss are often called “Watarai Shinto”), there is no strong evidence that it was commonly understood as shintō in the modern sense - a distinct religious tradition - predating an explicit statement in a treatise from 1419 written by the Tendai monk Rysōhen dealing with these topics. In the earliest sources the default reading was jindō, referring not exactly to a distinct system of beliefs, but rather to a “realm”of kami ultimately existing in Buddhist context. While Shinto did eventually develop into the tradition which came to define the kami, through the middle ages and the Edo period which followed, honji suijaku was the dominant paradigm, and permeated all spheres of society.

The early history of Amaterasu: sun, textiles and longing for companionship

An Edo period painting of Amaterasu emerging from the cave, by Kunisada Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

While the explanation of the basic nomenclature and a crash course in interactions between Buddhism and kami is now out of the way, before I’ll be able to move on to the impact of the medieval ideas on Amaterasu I need to briefly summarize her earlier history.

Through the article I will simply use the name Amaterasu consistently. However, it should be noted that the standard form of the name, 天照大神, in the middle ages and in the Edo period was often read not as Amaterasu Ōkami, but rather as Tenshō Daijin, in accordance with on’yomi or “Sino-Japanese” sign values. Therefore, don’t be surprised that this is the version used in titles of historical works mentioned. As a curiosity it is worth mentioning that this is actually the reading used fairly consistently in the first western source with reasonably reliable information about Amaterasu (unless I missed something even earlier), Engelbert Kaempfer's History of Japan from 1727.

On a similar note, I generally stick to describing Amaterasu as female. However, it needs to be pointed out that through the middle ages and in the Edo period male Amaterasu is also attested, depending on the source either replacing the female version or coexisting with her. Some modern authors go as far as speculating if Amaterasu wasn’t originally seen as male prior to being redefined as female, but this is not really fully provable.

The existence of a tradition according to which Amaterasu manifested in male form is already mentioned by the Tendai monk Jien (1155-1225). There are also sources providing ambiguous information about Amaterasu’s gender. In at least some cases such phenomena were a result of identification with figures either regarded as male or portrayed as androgynous in art, as I outlined in a recent article discussing the case of Amaterasu and Uho Dōji (who won’t be brought up here in any meaningful capacity, since I'm not going to focus on the Edo period). It’s not really possible to make a blanket statement on this matter, though.

Additionally it’s important to bear in mind that identification between two figures could transcend the gender of the parties involved. As you’ll see later, there were even cases of Amaterasu’s identification with a male figure actually resulting in traditions particularly strongly emphasizing her typical gender.

The Inner Shrine at Ise in 2008 (wikimedia commons)

Throughout her entire history Amaterasu has been associated with Ise and its Grand Shrine. According to the Nihon Shoki, that’s where she originally descended from heaven to earth, and where she later returned in order to be enshrined. The term “Ise Grand Shrine” actually refers to a complex centered on two major shrines, though, and only one of them, the Inner Shrine (内宮, naikū), is dedicated to Amaterasu. The kami of the Outer Shrine (外宮, gekū) is instead Toyouke.

The earliest history of Amaterasu is effectively unknowable due to lack of available sources. While she does appear both in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki in a central role, both of these works only date to the eighth century, and their historicity is often at best dubious. When exactly was her shrine originally established is a matter of debate: supporters of treating Nihon Shoki literally argue for 4 BCE (during the reign of the legendary emperor Suinin), but historians and archeologists favor more vague dating to either the fourth, fifth or seventh century. The earliest detailed records of specific religious ceremonies at Ise can only be found in an administrative protocol compiled in 804.

Historically it was quite popular among researchers to essentially assume being a personification of the sun is all there ever was to Amaterasu’s character, and that she derives her importance entirely from her solar role. Today this view is no longer accepted quite as firmly, and it is even sometimes questioned if this was necessarily her original function, though this is ultimately neither entirely provable nor fully relevant here.

Obviously, the classical Amaterasu also served as a royal deity presented as an ancestor of Japan’s imperial lineage. She was also treated as a symbolic source of its authority by extension of her role as a heavenly ruler commanding the kami. This is an example of the well documented phenomenon of clan kami (氏神, ujigami). However, based on archeological data Ise was not particularly important early on in Japanese history, and the area around it was sparsely populated as late as in the seventh century On top of that it would appear that, if the early texts are to be believed, emperors actually had an ambivalent relationship with her. It has been suggested that her classical position was only established during the reign of emperor Tenmu in the late seventh century, perhaps due to his personal connection to clans from the Ise area.

It’s important to stress here that on multiple occasions in history, in particular recent history, the connection between Amaterasu and emperors was channeled to nationalist and imperialist purposes. For instance, the Japanese colonial government in Korea funded the construction of a complex enshrining Amaterasu and emperor Meiji in the 1920s, and subsequently legally obliged students (among others) to attend ceremonies held there to foster loyalty.

The Outer Shrine in 2015 (wikimedia commons)

A key moment in the early history of Amaterasu was the introduction of the kami Toyouke (豊宇; literally “abundant food”) to Ise. A legend about her arrival is preserved in the aforementioned administrative protocol from 804. According to it, Amaterasu appeared to emperor Yūryaku (second half of the fifth century, if his historicity is to be accepted) in a dream to let him know that she is distressed and lonely, and on top of that can’t receive offerings of food according to proper protocol. She explained that the only way to solve all of these problems is to bring her a kami responsible for divine food (御饌津神, miketsu kami), Toyouke, who is to be found in Hiji no Manai in the Tanba Province. Thanks to this precise guidance, the emperor was able to instantly solve the problem, and Toyouke was moved to Ise, where she symbolically took the responsibility for food offered to Amaterasu.

Presumably, the legend contains at least a kernel of truth, and Toyouke was initially enshrined in a facility meant to fulfill a specific ritual role for the Inner Shrine, which in time grew to rival it in size and importance. Save for these details, much about the early history of Toyouke is even more unclear than in the case of Amaterasu, though. She is only mentioned in passing in the Kojiki under the name Toyoukehime no Kami (豊受姫神) in the account of the birth of Wakumusubi no Kami (和久産巣日神), one of the many kami who came into being as a result of Izanami’s death. However, this passage does not provide any information about her character, it merely states that she is Wakumusubi’s child. This tradition was of limited, if any, interest to the Outer Shrine clergy through the middle ages, as I’ll later demonstrate.

While Wakumusubi also appears in the Nihon Shoki, though with a slightly different genealogy, Toyouke is entirely absent from this work. You can find a claim on the contrary in Michael Como’s Weaving and Binding. Immigrant Gods and Female Immortals in Ancient Japan, but he essentially treats Ukemochi as identical with Toyouke and asserts the myth about Tsukuyomi killing the former is effectively about the latter. It doesn’t seem like any subsequent publications picked up this idea.

The final early source of information about Toyouke is the Tango no Kuni Fudoki (丹後国風土記; “Records of the Tango Province”). It presents her as one of eight “heavenly women” (天津乙女, amatsuotome) who at some point arrived at a spring near Mount Hiji to bathe. An old couple stole the clothes of one of them, rendering her unable to return to heaven. They subsequently ask her to become their daughter, since they have no children. She agrees, and for ten years lives with them, brewing sake which could magically heal “ten thousand ills”. The old man and woman prosper thanks to her. However, they eventually decide to tell her that she is not really their child, and should go back to heaven. She tells them that she has lived among humans for so long this is not an option for her anymore, and leaves in anger. She only calms down after reaching a different village, Nagu, where she is eventually enshrined under the variant name Toyoukanome no Mikoto (豊宇賀能売命).

Due to involving a heavenly being having to stay on earth due to her clothes being stolen, this myth has been compared to the better known Hagoromo. Michael Como also argues that it might reflect the perception of Toyouke as a Daoist immortal (hence her ability to bew something akin to the fabled Daoist alchemical elixirs meant to prolong life), similarly to how the legend of Urashima Taro does. While I found his Nihon Shoki argument somewhat dubious as I said, I think this is an interesting point which warrants further study. Similar possibility about Toyouke’s character has been suggested by Bernard Faure too.

It’s also worth noting a possible reference to the Tango no Kuni Fudoki myth has been identified in a painting of the two shrines of Ise from the collection of Shōryakuji, a Buddhist temple located in Nara (seen above; screencapped from Talia J. Andrei's Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara, for educational purposes only). It depicts eight female figures standing on a cloud around a container used to make sake in the proximity of the Outer Shrine.

Amaterasu and Buddhism: the ambivalent beginnings

Early sources pertaining to Ise discussed in the previous section are invaluable when it comes to Amaterasu’s position and her connection with Toyouke, but they don’t really shed any light on the development of associations between her and Buddhist figures. Quite the opposite - they indicate that around the year 800, even basic Buddhist terms like “pagoda”, “monk” or “sutra” were considered taboo (忌み, imi) by priests of the Inner Shrine, much like these pertaining to conventional sources of religious impurity like violence, death or illness. However, Mark Teeuwen notes at the same time these very priests most likely took part in Buddhist ceremonies themselves, and there is even some evidence that in the eighth century a Buddhist temple existed in Ise.

The reasons behind the implementation of the taboo were likely largely political, rather than strictly religious. For context: in the second half of the eighth century, empress Shōtoku famously appointed Buddhist monks to various prestigious positions in the royal court. Dōkyō from the Hossō school was even temporarily elevated basically to the rank of her equal (though he eventually fell from grace). This was generally poorly received by other officials, who might have viewed it as an attempt at establishing Buddhist theocracy in place of hereditary monarchy. This in turn likely led to tensions and fueled various succession controversies in subsequent decades. Further problems, like untimely deaths or exile of various members of the imperial family, kept accumulating, and by 804 the prestige of the court was severely damaged. Furthermore, there is evidence that there were various economic conflicts of interest between the Ise clergy and local Buddhist monks.

A sixteenth century painting of emperor Kanmu (wikimedia commons)

Since the oldest source to mention the taboo is an administrative, rather than religious, text, it is not impossible that it was intended by emperor Kanmu as a way to diffuse all these social and political tensions. Mark Teeuwen suggests his goal might have been a way to restore the prestige of his family and create a center of symbolic ancestral cult which would offer him additional legitimacy independent from the Buddhist establishment residing in Nara, which was crucial for many of the previous emperors. As a lifelong student of Confucian philosophy, he likely found many models to draw from in Chinese texts. His vision of Ise was presumably that of an ancestral mausoleum.

Regardless of Kanmu’s decisions, in the long run Buddhism retained its influence in royal affairs. In fact, it was arguably this emperor himself who indirectly caused its revitalization. In 804, he sent two young monks, Saichō and Kūkai, to China. They returned with something previously largely unknown in Japan: esoteric Buddhism. The new schools they established, Tendai and Shingon, captivated the imagination of virtually all strata of society in the nascent middle ages.

Amaterasu, too, came under esoteric Buddhist influence, and gained new roles, often completely detached from her earlier character - or at the very least from the part of it firmly tied just to the ruling family. Mark Teeuwen partially jokingly refers to this chapter in her history as an “escape” from Ise and notes that for a time she has “shaken off the imperial shackles”.

There was a material aspect to these processes in addition to the purely theological considerations. In the Kamakura period, the role of warrior classes grew and the imperial court weakened. As a result, the Ise clergy - the Arakida clan of the Inner Shrine and the Watarai clan of the Outer Shrine - gained greater autonomy. The emperors weren’t able to enforce a symbolic monopoly on Ise, which therefore no longer served just as a center of ancestral cult. The downside was the loss of most of the imperial funding, which necessitated innovation to secure other sources of patronage.

The Ise taboos established earlier were not exactly abandoned, but the clergy found ways around them in order to enable Amaterasu to thrive in this new environment. A summary of the theological solution they developed is provided in Nakatomi Harae Kunge (中臣祓訓解; “Reading and Explanation of the Nakatomi Purification Formula) from the late twelfth century: “although on the surface performing ceremonies which are different from the Buddhist teachings, [Amaterasu] in essence protects the Buddhist laws.” Additionally, a myth reinterpreting one of the most famous episodes from the entire Buddhist canon, but with Amaterasu as a new protagonist, was developed to justify the taboo’s existence. I’ll discuss it in a separate section later on.

The reinvention was evidently successful. There is little evidence for widespread worship of Amaterasu in earlier periods. She was effectively little more than a royal deity. Even courtiers had limited, if any, knowledge of her. Only in the middle ages did she come to be widely recognized as a major figure in the Japanese religious landscape among all strata of society. Paradoxically it was the partial detachment from the imperial family that let Amaterasu claim a uniquely elevated position in the pantheon.

One of the best sources of evidence of Amaterasu’s newfound popularity are standardized oath formulas (起請文, kishōmon). In the Kamakura period, she came to appear in them quite frequently. She was invoked either simply as the foremost kami, or alternatively as the “lord of the land” (ie. Japan; 国主, kokushu). Either way, her purpose, much like those of other of the invoked figures, was to guarantee the oath will be upheld, and to punish those who will break it.

The spread of Amaterasu to new audiences resulted in the rise of numerous new interpretations. That’s where the already briefly discussed idea of honji suijaku came into play.

A twelfth century painting of the Buddha Dainichi (wikimedia commons)

As I said earlier, despite the popular understanding of this term honji suijaku did not necessarily just signify correspondences between kami and buddhas. However, in Amaterasu’s case the earliest example actually does match this model. She came to be associated with the Buddha Dainichi (大日, literally “great sun”; from Sanskrit Vairocana).

Some authors, like Bernard Faure, argue that the establishment of a link between Amaterasu and Dainichi was effectively the core of the early honji suijaku as a whole. Purportedly the belief that a connection existed between them went all the way back to the teachings of the famous monk Gyōki, active in the first half of the eighth century. The historicity of this claim is uncertain, but it was understood as historical truth in the discussed time periods, at the very least. Anna Andreeva, relying on earlier studies by Satoshi Itō, notes that it would appear Seizon’s (成尊; 1012–1074) Shingon Fuhō San'yōshō (眞言付法纂要抄; “An Abbreviated Compendium of the Transmission of Shingon Buddhism) from 1060 has a strong claim to being the oldest attested example which can be properly dated.

While other Buddhas, such as the historical Buddha, Amida (Amitābha), Miroku (Maitreya) or Yakushi (Bhaiṣajyaguru), are obviously also present in Japanese Buddhism, historically, especially prior to the rise of Amida-centrist schools, Dainichi was by far the most important one. This is especially pronounced in Shingon, where he is recognized as the “first Buddha” (Ādi-Buddha). Dainichi’s importance coupled with his solar associations made him a suitable match for Amaterasu in the eyes of theologians.

Amaterasu’s solar role is pretty widely acknowledged in Buddhist sources, and she could be labeled as a “solar deity”, nisshin (日神). She was also identified with Nittenshi (日天子), the Buddhist version of the Hindu sun god Surya. However, Nittenshi could also function as a distinct figure and had his own iconography.

A twelfth century hanging scroll showing Nittenshi in the company of attendants (Kyoto National Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The development of a connection between Amaterasu and Dainichi brought a number of changes to Ise. As an extension of it, the Inner Shrine and Outer Shrine at Ise came to be identified with the Womb Realm mandala and the Diamond Realm mandala, closely associated with him.

The Ise clergy additionally argued that the taboo observed as the shrines does not impact Amaterasu’s connection to Dainichi - rather she (and by extension Toyouke as well) represents not a mere trace of this Buddha, but “original enlightenment” (hongaku). A new systematization of kami was built around the idea: at Ise, only Amaterasu and Toyouke were regarded as belonging to the category of “kami of original enlightenment”, with other divided into “kami of inception of enlightenment” (those who had to actively embrace Buddhism) and “kami of delusion” (those who opposed it). Similar categories were employed in different areas too, though, with the head local kami, for example Suwa Daimyōjin or Sannō (山王), taking the same role as Amaterasu at Ise.

While Dainichi can be considered Amaterasu’s essential honji suijaku pair, I already pointed out, it was hardly unusual for a specific figure to develop multiple connections within the honji suijaku framework, though, and this holds true for her too.

Amaterasu, Enma and other functionaries of the underworld

Enmaten (wikimedia commons)

Next to Dainichi, Amaterasu’s best attested Buddhist “counterpart” is not a Buddha, but rather a deva, specifically Enma, the judge of the dead. While many other devas present in Japanese Buddhism largely languish in obscurity today, at least in popular perception, he is probably the most recognizable one next to the Four Heavenly Kings, so I do not think much of an introduction is needed. Even if you are not particularly interested in the history of religions, chances are you’ve seen him in one piece of media or another.

Technically there are two distinct forms of Enma in Japanese tradition - Enmaten (焔摩天), who is more of a “classical” Hindu-style deva fairly similar in appearance to the original Yama, and the more popular Enma-ō (閻魔王; “king Enma”), styled after the bureaucratic Chinese underworld deities - but this distinction is not very important here. His rise to prominence in Japan started in the early ninth century at the latest, and by the ten century he was also joined by Taizan Fukun (東岳大帝; originally Taishan Fujun), a similar deity incorporated into Buddhism from Daoism. The latter was essentially the model for all of the other judges of the underworld: from the Buddhist kings of hell, to various local gods who took this role in the popular religion of Qing China. He might have even influenced the development of Matarajin in medieval Japan, but that’s a topic for another time.

It seems that a link between Amaterasu and Enma was initially established through an intermediary, specifically Seoritsuhime (瀬織津姫). She is identified with the king of hell in the Nakatomi Harae Kunge. While much about this text remains a mystery, in this case the logic behind the equation is quite clear - both of them were invoked during ritual purification. The means were not quite the same: Enma throws the sources of impurity into the deepest hells, while Seoritsuhime casts them into the ocean. Still, the level of similarity was sufficient to warrant establishing a connection.

Seoritsuhime is described both as a servant of Amaterasu, and as her aramitama (荒魂), literally “rough spirit”. This term designates the wrathful, or at least impulsive, aspect of a given kami. In Nakatomi Harae Kunge Seoritsuhime as a manifestation of Amaterasu is also more specifically described as ara-tenshi (荒天子), “heavenly emperor manipulating the brutish force”.

An Edo period depiction of Taga Myōjin from the collection of Kyoto City University of Arts (via Bernard Faure's Fluid Pantheon; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

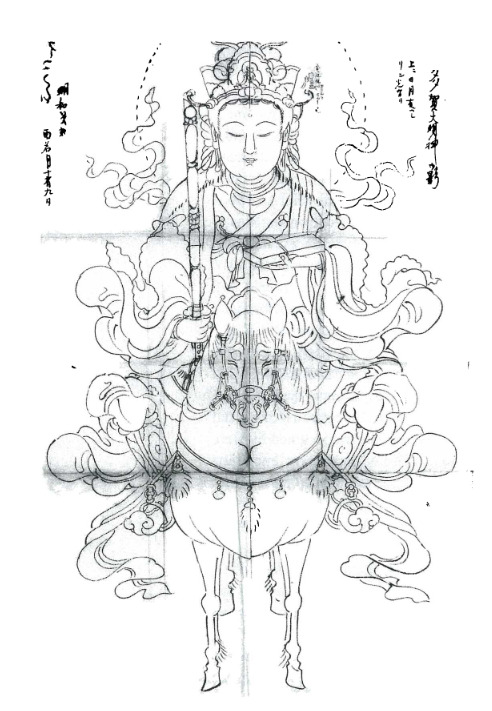

Tenshō Daijin Kuketsu (天照大神口決; “Oral Transmission Pertaining to Tenshō Daijin”), a fourteenth century theological treatise, also embraces the equation between Enma and Amaterasu. It explains that he corresponds to the form of Amaterasu associated with the Taga shrine, Taga Myōjin (多賀明神). She has a distinct iconography, and fairly consistently appears as a horsewoman on either a black or white steed (always shown frontally), with a sword in one hand and a box with a sutra in the other.

The same source also equates Amaterasu with Godō Daishin (五道大神; originally Wudao Dashen), the “god of the five paths”, another king of hell. In the Nakatomi Harae Kunge, it is instead a purifying kami, Haya-Akitsuhime (速秋津比売神), “the beloved of the dragon king Nanda”, who corresponds to him, though. The passage establishing this also mentions a similar link between yet another purifying kami, Ibukidonushi, and Taizan Fukun (curiously, the explanatory line states that the river where Izanagi purified himself after fleeing from Izanami is identical with Mt. Tai, the residence of Taizan Fukun). However, the latter is also said to be the aramitama of Toyouke.

A Japanese statue of Baozhi (Kyoto National Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Tenshō Daijin Giki (天照大神儀軌; “A ritual manual [for the worship] of Tenshō Daijin”) states that Amaterasu as a judge of the dead commands eleven messengers referred to as “princes”. It’s not easy to date this text precisely, though it’s clear it was already in circulation by 1164. It claims to contain knowledge originally revealed to the legendary Chinese monk Baozhi (寶誌; 418-524), best known from a legend commonly referenced in art in which he tears his face apart to reveal the visage of bodhisattva. The text effectively redefines Ise itself as a place where the underworld officials gather, imbuing the temple complex with new meaning, detached from its older role as a center of royal ancestor cult.

The eleven messengers listed are Zuikō Tenshi (a manifestation of Enma), Ryūgū Tenshi (dragon king Nanda), Suijin Tenshi (dragon king Batsunanda), Tenkan (“magistrate of heaven”), Chikan (“magistrate of earth”), Shimei (an underworld official), Inin Tenshi (equated with Izanagi and with Shiroku, an underworld official paired with Shimei in other sources), Kōzan Tenshi (Taizan Fukun), Godō Daishin, Kazenagashi no Kami and Okitama (a water deity equated with Suikan, “magistrate of water”). They correspond to various auxiliary shrines at Ise. Each of them is said to command a retinue of “four thousand trillion spirits”. While abstractly big entourages are quite common in medieval sources, from Michizane’s 105000 thunder god subordinates to Tenkeisei’s 84000 shikigami, even by these standards the number is unusually high.

The Enmaten mandala, with Taizan Fukun (middle of the top row) and Shimei, Godo Daishin and Shiroku (bottom row) shown among his attendants (wikimedia commons)

The lists of underworld officials serving Amaterasu show a considerable degree of overlap with these present in ritual texts Enmaten Ku (閻魔天供) and Taizan Fukun no Sai (泰山府君祭; you may know it from the story of Tamamo no Mae). Notably, Tenkan, Chikan, Suikan, Shimei and Shiroku are all members of Enma’s entourage in origin. The last two are scribes responsible for keeping track of human lifespans, but the role of the former three is not well understood.

Another deity present both in these rituals and in Amaterasu’s entourage, Godo Daishin, is a king of hell in his own right. His origin is unclear, though the oldest sources which mention him are Chinese apocryphal episodes from hagiographies of the historical Buddha. As the “god of the five paths”, he is responsible for assigning the dead to one of the five realms of rebirth: these of gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts or hell. Notably missing is the asura realm, which didn’t particularly catch on in East Asian Buddhism. In the oldest sources, he is portrayed as somewhat inept and after meeting the Buddha implores him to teach him how to fulfill his role better.

Enmaten Ku and Taizan Fukun no Sai attained a considerable degree of popularity in the eleventh and twelfth centuries due to the spread of the bureaucratic image of hell, and many laymen sought Buddhist monks (in the case of the former ritual) and onmyōji (in the case of the latter) who could perform them. They were supposed to heal illnesses, prolong life, secure an easy birth or simply to guarantee good fortune. It’s not impossible that furnishing Amaterasu with a similar role to their central deities was meant to let her clergy from Ise capitalize on the popularity of such rituals too. The spread of the new image of Amaterasu as a judge of the dead was also likely tied to her judiciary role in the already discussed oath formulas, where she essentially acts as a supernatural enforcer of legal claims.

Hokusai's drawing of three dragon kings, including Nanda and Batsunanda (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The final matter that needs to be addressed here is the presence of dragon kings Nanda (難陀) and Batsunanda (跋難陀; Sanskrit Upananda) in Amaterasu’s underworld entourage. In contrast with their peers, they do not have anything to do with Enma. In Buddhist cosmology, they support the cosmic mountain Sumeru, on which the highest devas like Indra and Brahma reside.

More context on their connection to Ise is provided in the treatise Bikisho (鼻帰書), which cites the Outer Shrine priest Tsuneyoshi Watarai (度会常昌; 1263-1339) as its source. It actually states that all eight of the dragon kings are protectors of Ise, though also that only two, one blue and one white (with no names provided), can be used to represent respectively the Inner Shrine and the Outer Shrine. The connection is said to depend on their role as protectors of the Womb Realm and Diamond Realm mandalas. Multiple sources from Ise indicate they were believed to dwell under the central pillars of the Inner Shrine and the Outer Shrine, in this context additionally identified with the cosmic abode of the gods, Mount Sumeru.

Amaterasu, Toyouke and Brahma (times two)

Bonten, the Japanese version of Brahma (wikimedia commons)

While Dainichi made a natural match for Amaterasu, and the reasons behind her association with Enma, while less obvious, aren’t hard to understand either, the third Buddhist figure most commonly associated with her, Bonten, is quite surprising. This deity, the Japanese Buddhist guise of Brahma, has limited presence in popular understanding of Buddhism, but generally much like his Hindu forerunner he is portrayed as a distant deity with limited interest in everyday human affairs. And yet, in medieval Japan Brahma was identified with a figure both commonly worshiped and understood as quite active.

This tradition is documented in Tenshō Daijin Giki. It reaffirms that Amaterasu - seemingly treated as a male figure in this case - is the Japanese guise of Dainichi. However, in the “Realm of Form” - a Buddhist term referring to the world inhabited by humans and deities - he takes the guise of Bonten, and acts as the deva king of Japan. His life will last a total of 105000 years, and he will defend exactly 1000 rulers over the course of this period, before ascending to the Realm of Form to hear the preaching of Miroku. He will also help the faithful reach it.

The already discussed Tenshō Daijin Kuketsu also recognizes the equivalence between Amaterasu with Bonten, though it also furnishes her with a similar connection to the other ruler of the devas, Taishakuten (Indra), and states that both of these equations depend on the doctrine of Abhidharmakośa. Perhaps more unexpectedly, the same work also equates Amaterasu with Shōten (聖天, literally “noble god”; a Japanese form of Ganesha), specifying that this reflects a Shingon view. However, the thirteenth century scholar Ieyuki Watarai (詳細表示; 1256-1356) in his Jingi Hishō (神祇秘抄; “Secret Comments about the Deities”) mentions a different tradition in which this god’s connection with Amaterasu is less direct. He is said to be identical with a nameless “heavenly fox” (天狐, tenko) who acts as her acolyte.

Yet another text already brought up in the previous section, Nakatomi Harae Kunge, does not equate Amaterasu with Brahma outright, but it does redefine terms from classical mythology around him. The High Plain of Heaven (高天原 Takamagahara) is said to be identical with the “First Meditation Heaven of the Realm of Form, ruled by Bonten”. Furthermore, the collective label Yaoyorozu no Kami (八百万の神; literally “eight myriad kami”) is said to encompass “Bonnō, Taishaku, the innumerable devas, the four Great Heavenly Kings, the innumerable devas of Bonnō, and eighty four thousand kami.”

The newfound interest in Brahma in the middle ages reflected an intellectual development arguably unparalleled in earlier Japanese religious tradition - a preoccupation with cosmology.

Kojiki and Nihon Shoki obviously do deal with this topic, but the relevant sections are incredibly brief. This new discourse about cosmology was, at its core, Buddhist, but a major issue was that Japanese Buddhism was not very concerned with cosmology either. The two main sources of inspiration were, therefore, not contemporary Buddhist literature, but Chinese (mainly Daoist) texts on one hand, and accounts of Hindu cosmology, especially the Puranas, preserved in Buddhist sources on the other. Figures such as Pangu, the Three Pure Ones, Shiva or Brahma as a result attained considerable renown among Japanese theologians, who reinterpreted myths about them to suit local context, creating new narratives in the process.

A contemporary statue of Kuni no Tokotachi (wikimedia commons)

In some cases the poorly defined primeval kami from classical mythology could be incorporated into the new visions of cosmology created in the middle ages. Ame no Minakanushi from the Kojiki and Kuni no Tokotachi present both in this work and the Nihon Shoki are both well attested in that context, though references to Ame Yuzuru Hi Ame no Sagiri Kuni Yuzuru Hi Kuni no Sagiri from the Sendai Kuji Hongi can be found too. They were effectively treated as almost interchangeable, or as stages of emanation of the same entity, as documented for example in the writings of the Tendai monk Jihen (慈遍).

Two strains of cosmological speculation, these focused on Brahma and primordial kami, were in particular enthusiastically embraced by the Outer Shrine clergy at Ise, who utilized both of them to improve the standing of Toyouke. As I mentioned before, her role, while seemingly initially relatively minor, grew with time. In many regards, she came to be presented as Amaterasu’s equal. She was furnished with an association with the moon to match Amaterasu’s solar character, for example. The first attempts at elevating Toyouke through theological speculation weren’t necessarily grand in scale. She was simply identified with other kami of similar characters every now and then, for example with Uka no Mitama. An isolated source, a letter from the early Kamakura period, appears to present her identical with Ninigi, Amaterasu’s grandson, instead, but this evidently did not stick.

A breakthrough occurred in the late thirteenth century. The outer shrine clergy developed a view that Toyouke didn’t originate as a servant brought in to deal with Amaterasu’s loneliness and other needs, but rather a primordial kami, identical with Ame no Minakanushi or Kuni no Tokotachi. Toyouke in this guise was the foremost kami of heaven, and Amaterasu “merely” the foremost kami of earth.

However, as I already pointed out, the new cosmologies which influenced this reinterpretation of Toyouke depended not only on classical mythology. Therefore, the Outer Shrine’s kami could also be identified with Brahma, or credited with controlling the proper flow of qi and thus yin and yang, following a Daoist model. Much of this theological speculation might have originated in the works of a single priest, Yukitada Watarai (度会行忠; 1236-1305), though he was far from the only contributor.

It’s worth pointing out that there was a practical material component to the theological speculation about the identity of Toyouke. Regardless of the relation of their respective kami, Inner and Outer Shrine were ultimately rivals competing for patronage. To present Toyouke as equally, if not more, important as Amaterasu was also a way to make potential donors, from shoguns to commoner pilgrims, more inclined to support the Outer Shrine. While prior to the Kamakura period Ise could securely depend on imperial funding alone, that changed with the weakening of the court. Therefore, securing new supporters was vital for their continuous activity. This remained the case through the Edo period as well, but this topic obviously goes beyond the scope of this article.

Identification of both Toyouke and Amaterasu as Brahma was not necessarily contradictory thanks to the existence of sources in which more than one Brahma appears. Nobumi Iyanaga points out that two Brahmas, Mahābrahmā Śikhin (ie. Brahma as the king of the gods) and Mahābrahmā Jyotiṣprabha (“Great Brahma of Brilliant Light”), appear in the Yamato Katsuragi Hōzanki (大和葛城宝山記), with one reflecting traditional portrayals of Brahma and the other representing a reinterpretation of an account of Vishnu as a creator figure. Both of the titles used appear in the enumeration of deities listening to the Buddha’s teachings in the Lotus Sutra. Two Brahmas also appear in the Bikisho, where “king Brahma” descends from heaven, but instantly starts longing for a friend. In response, a deity named Harama, an alternate transliteration of Brahma into Japanese, appears to him.

The notion of Toyouke and Amaterasu being two Brahmas might have developed in the thirteenth century at Senkūin, a Buddhist temple closely affiliated with the Ise shrines. A text from this location dated to between 1240 and 1275 states that Toyouke, addressed as identical with Ame no Minakanushi, corresponds to Shiki Daibontennō (尸棄大梵天王; “emperor Mahābrahmā Śikhin”) and Amaterasu to Kōmyō Daibontennō (光明大梵天王; “emperor Mahābrahmā Jyotiṣprabha”). It also specifies Toyouke is male and Amaterasu female, which reflects splitting Brahma into a male-female cosmogonic pair. Nobumi Iyanaga points out the theological treatise Tenchi Reikiki (天地麗気記) goes a step further: the two deities are said to partake in intercourse. He suggests this represents a development of the motif of Brahma longing for a friend in the Bikisho. Tenchi Reikiki also states the couple personifies the Womb Realm and Diamond Realm.

A Kamakura perioid painting of Kūkai holding a vajra (wikimedia commons)

As a digression it’s worth pointing out that while the Tenchi Reikiki was only written in the Kamakura period, it was actually attributed at the time to Kūkai, who lived centuries earlier. Obviously one reason was that there’s no better way to make a treatise seem more authoritative than to claim it was written by a celebrated historical figure. However, it’s also worth pointing out that at some point a connection between Kūkai and Amaterasu developed. A tradition known from a number of works, for example Monkan’s treatise Himitsu Gentei Kuketsu (秘密源底口決) presents him as a manifestation of her.

The Watarai theories about the nature of Toyouke and Amaterasu have originally been written down in the Kamakura period in the so-called “secret books''. This term has been used to refer to them collectively since the Edo period, when they were standardized for a relatively brief time into a “canon” of sorts. While tradition has it that there were five of them, research revealed the existence of further texts in medieval tradition, with one rediscovered in 1955, for example.

At least in theory, the individual Watarai books present information contained within as a special sort of secret, designated by the Buddhist term shōgyō (聖教; literally “sacred teachings”). Originally it referred to the teachings of the historical Buddha, or to the Buddhist canon more broadly, but in medieval Japan the term came to refer to specific kinds of knowledge transmitted by monks and other religious specialists in general.

While sometimes referred to as “secrets” in English, shōgyō were not necessarily impossible to share. Through the entire middle ages, many temples and shrines all across Japan effectively actively built their identity around making it known that they possess religious secrets worth knowing and can transfer them. Sometimes, they were intentionally “leaked” to nobles, imperial courtiers or fellow clergymen to spark interest. They were also utilized in annual “debate rituals” (論義会, rongie) held by authorities for religious scholars, who treated them as a way to hone their rhetorical skills and gain new theological insights.

The divine and the vulpine at Ise: Amaterasu, Dakiniten and Sankoshin

The Dakiniten mandala (wikimedia commons)

The topic of shōgyō is fundamentally linked with ambivalent Buddhist figures which in medieval Japan came to be associated with the notions of non-duality combining enlightenment and ignorance, such as dakinis, which commonly figured in such “secrets”. While dakinis do not appear in the cosmological myths from the Watarai books, they nonetheless did play a role in the developments pertaining to medieval Amaterasu. A link between her and the dakini par excellence, Dakiniten, developed due to their shared connection with Dainichi. Under his original name Mahavairocana, Dainichi can be portrayed as a subduer of dakinis, taking the guise of Mahakala (Makaraten) in this context. The singular Dakiniten as a result of this association could be identified with Dainichi outright, as attested in the Rinnō Kanjō Kuden (輪王灌頂口傳), dated to the late Kamakura period.

The link between Amaterasu and Dakiniten is chiefly known from the Shingon ritual sokui kanjō (即位灌頂), “enthronement initiation”, meant for emperors freshly ascended to the throne. It was first performed for emperor Fushimi in 1287, and remained a part of ascension ceremonies all the way up to 1846. In this context, Amaterasu outright appears in the guise of Dakiniten. A similar statement can be found in Tenshō Daijin Kuketsu, which calls Dakiniten the honji of Amaterasu (it also links Dakiniten with Fujiwara no Kamatari and the rise of the Fujiwara clan, but I’ll cover that elsewhere in the future).

Keiran Shūyōshū specifies that the shinko was an appropriate form for Amaterasu because it is the only animal capable of emitting light on its own. This ability in turn reflects the fact that its body was identical with the wish-fulfilling jewel, a frequent attribute of Buddhist figures; the name is self-explanatory. Alternatively, the animal could be described as possessing three tails, each ending in a wish-fulfilling jewel. By the fourteenth century, this object was firmly associated with Amaterasu as well. This led to the development of the view that Nyoirin Kannon (如意輪観音), a form of Kannon directly linked to the wish-fulfilling jewel, was Amaterasu’s honji. The shinko similarly could be identified with this bodhisattva. Granted, so were prince Shotoku, Ryōgen and numerous other figures, but that’s a separate topic not directly relevant to this article.

A different belief developed around the shinko at Ise. Here this supernatural animal came to be identified with Sankoshin (三狐神), literally “three fox deity” or “three fox deities”. Despite the triplicity implied by the name, sources such as Tamakisan Gongen Engi (玉置山権現縁起) clearly describe Sankoshin as a singular figure who acted as the “king of the heavenly foxes” (天狐王, tenko-ō).

It is presumed that Sankoshin's name was in origin a derivative of Miketsu no Kami (御食津神), the kami of Miketsu, the granary of the Outer Shrine. The development of Sankoshin might have started as a misreading or wordplay, with Miketsu (御馔津) transformed into the homophone mi ketsu, “three foxes” (三狐). This phrase in turn can be alternatively read as sanko, as in the case of Sankoshin.

Miketsu no Kami is otherwise associated, or outright identified, with Uka no Mitama, who is obviously not a fox, let alone three foxes; or alternatively with Toyouke, who has even less to do with these animals; you might recall she is described as a miketsu kami in the legend of her arrival in Ise. Older copies of Nakatomi Harae Kunge also affirm this equation, but later on the reference was substituted for a statement supporting the equivalence between Toyouke and Ame no Minakanushi favored by the Watarai priests.

Sankoshin in the middle ages appeared in rituals from Ise associated with the kora (originally 子良, later also 狐良). This term refers to a class of female shrine attendants associated with the Outer Shrine at Ise. Jingi Hishō asserts they were manifestations of Dakiniten, and on the basis of homophony links their name with 狐 (ko), “fox”.

Part of a hanging scroll depicting Dakiniten riding on a fox (wikimedia commons)

Elsewhere, shinko is treated as another name of Dakiniten, or alternatively of her fox mount (which lacks serpentine traits proposed by Teeuwen, but sometimes does have snakes coiling around its legs and neck). It’s also a part of her well attested epithet Shinko-ō Bosatsu (辰狐王菩薩), “Bodhisattva King of Astral Foxes”. This connection is also partially responsible for the development of another of her titles, Shindamani-ō (真陀摩尼王), “king of the wish-fulfilling jewel”.

Being able to grant specific wishes immediately was commonly attributed to Dakiniten in the middle ages and beyond. However, due to her ambivalent perception and peripheral role between devas and demons in Buddhist theology it was commonly believed that the worldly benefits granted by her do not last and in the long run might lead to misfortune. With time, related rituals often came to be perceived negatively, often based on highly dubious reasons, as I discussed recently in another article. The ambivalent perception of Dakiniten ultimately was not unlike that of the animals she came to be associated with.

I plan to cover Dakiniten in more depth at some point, but I will only note here that her connection with foxes has a rather interesting history. Originally, dakinis were associated with jackals in India, due to their similarly unfavorable perception. When Buddhist texts dealing with this topic were transmitted to China, references to these animals posed a challenge to the translators, who were entirely unfamiliar with them. Based on context it was established that the name of a fox-like legendary animal, the yegan (野干), would make for a sensible translation. Since the yegan was described as fox-like, and since foxes in general had a major role in religion and literature of China at the time, eventually comparisons with foxes started to show up. Most notably, in the Tang period Śūraṅgama Sūtra the word dakini is provided with the gloss humei gui (狐魅鬼), something like “fox sorceress demon”. While unique, this term might have influenced the development of the image of dakinis in general, and Dakiniten in particular, in Japan.

A thirteenth century depiction of Benzaiten with entourage (wikimedia commons)

To go back to the core topic of this section, the development of a link between Amaterasu and Dakiniten had one more consequence: the establishment of a similar connection between Toyouke and closely related Benzaiten at Ise, to keep the theme of mirroring associations. This goddess is the Buddhist form of Saraswati. Today, she is best known as one of the Seven Gods of Luck, who emerged as a group in the Edo period, though her history goes further back and she enjoyed considerable popularity through the middle ages.

Outside of Ise, it was commonly Amaterasu herself rather than Toyouke who came to be linked to Benzaiten. According to a legend which originated on Chikubu Island, Benzaiten first appeared in Japan during the reign of emperor Kinmei, and instantly announced she is a manifestation of Amaterasu. A less direct reference might be present in the already mentioned Taiheiki, where Yoshisada Nitta at one point says he heard Amaterasu at times manifests in the form of a “dragon god of the blue ocean”, which might be an allusion to a common symbol of Benzaiten.

Benzaiten and Amaterasu could also be associated without being identified with each other. In a myth tied to the tradition of wandering blind singers (a group traditionally believed to be under her protections), she effectively replaces Ame no Uzume, and lures Amaterasu out of the cave by playing her biwa. In the Asamayama Engi (朝熊山縁起), she is addressed as Amaterasu’s mother instead, though she ultimately only plays a minor role in contrast with her daughter. The text largely revolves around Amaterasu (as noted by Anna Andreeva portrayed here as a “great conversationalist”) explaining theological matters to the monk Kūkai.

Amaterasu, Aizen and sericulture

The wisdom king Aizen (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In addition to her links to Buddhas and devas, Amaterasu also offers an example of identification between kami and wisdom kings. They enjoy an elevated position among Buddhist figures, almost on par with Buddhas and bodhisattvas. She could specifically be identified with arguably the second most important member of this category, Aizen Myōō. Since he is regarded as a wrathful manifestation of Dainichi, the reasons appear fairly straightforward. Linking him with Amaterasu goes back at least to Eison, a long-lived thirteenth century Shingon monk. The connection additionally reflects Amaterasu’s association with the wish-fulfilling jewel. Aizen was outright identified with this object, which is actually responsible for many of his own associations. Last but not least, Aizen and his fellow wisdom king Fudō were identified with the same two mandalas as the two shrines of Ise. On this basis it was not hard to link Aizen with Amaterasu.

However, once again, association does not necessarily equal conflation. Therefore, Aizen and Amaterasu could also appear as two distinct figures in the same sources. For example, both textual and iconographic instances of a triad consisting of both of them and another wisdom king, Fudō, are known. The occasional identification between Aizen and Amaterasu is not the reason behind his appearance here. Instead he and Fudō are present because they are an archetypal Buddhist dyad used to represent duality.

The triad is a medieval reinterpretation of the cave myth which played a role in an initiation rite (灌頂, kanjō) focused on Amaterasu. In this context both of the wisdom kings take the roles of “rock cave assistants”, with Fudō corresponding to Takuhatachijihime (the mother of Ninigi and younger sister of Omoikane) and Aizen to Tajikarao (who famously opens the cave in the classical version of the myth). The opening of the cave Amaterasu hid herself in was compared to the opening of the legendary Iron Stupa, said to exist somewhere in the south of India. This event, as Buddhist treatises record, led to the reveal of esoteric knowledge to the early Mahayana thinker Nagarjuna. In Tenshō Daijin Kuketsu, it is actually Amaterasu herself who was transmitted to him by the bodhisattva Kongōsatta (Vajrasattva).

To go back to the depictions of the Amaterasu triad, another thing worth pointing out is that a unique iconographic variant of her appears in them: seated on the back of a horse, with a solar disc and scales in her hands. While at a first glance this might sound similar to already discussed Taga Myōjin, there is actually a difference: the latter is always depicted frontally, not facing left, in contrast with the other mounted form of Amaterasu.

A depiction of Memyō from the fifteenth or sixteenth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

However, Bernard Faure notes these paintings resemble yet another figure she could be equated with, Memyō Bosatsu (馬鳴菩薩; “horse neigh bodhisattva”). This name originally referred to the Buddhist author Aśvaghoṣa, but in this context it instead designates a sericultural deity of Chinese origin first attested in the Tang period, for example in a short text attributed to Varjabodhi. However, while the Chinese original, Maming Pusa, is male, his Japanese counterpart is generally portrayed as a female figure, especially in texts stressing her connection to Amaterasu.

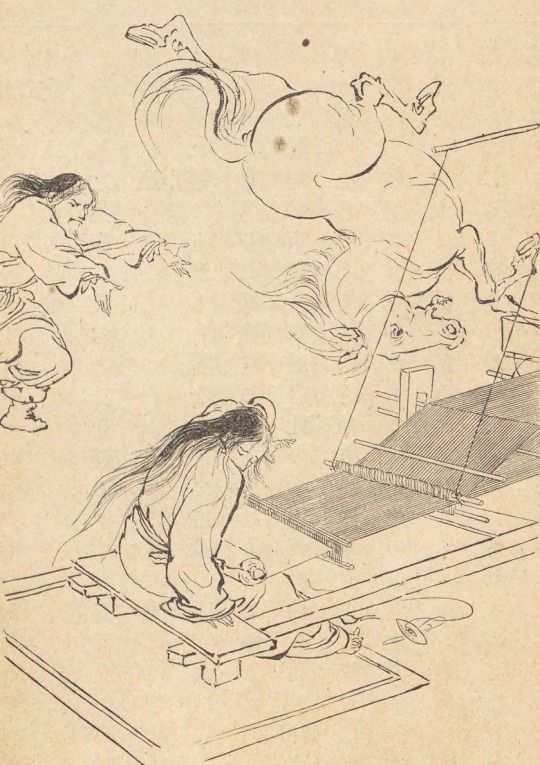

A Meiji period illustration of Susanoo throwing the carcass of Ame no Fuchikoma into Amaterasu's weaving hall (wikimedia commons)

Presumably the two initially came to be associated with each other because of their shared interest in sericulture and weaving. The classical myth portraying Amaterasu as a weaver, in which Susanoo throws the carcass of the horse Ame no Fuchikoma into the room where she is engaging in this craft, has been channeled to highlight why she would be identified with a deity portrayed on horseback.

While Memyō is arguably the highest profile Chinese figure Amaterasu was identified with (unless you want to make a case for Enma but that would be a bit of a reach), it’s worth noting that there’s another such case. However, it involved a historical figure rather than a deity. While presenting Buddhist patriarchs or rulers as manifestations of Buddhas or deities was par for the course, this one strikes me as quite unique.

Yang Guifei, as depicted by Shōen Uemura (wikimedia commons)

Jindai no Maki Hiketsu (神代卷祕決) records a tradition according to which Yang Guifei, a consort of emperor Xuanzong of Tang, was a manifestation Amaterasu. It depends partially on the preexisting belief that the former did not commit suicide, but instead escaped to Japan, and came to be enshrined in the Atsuta Shrine, which on the account of its picturesque location was sometimes identified with Penglai, the land of Daoist immortals. A related legend is recorded in the sixteenth century treatise Utaishō (謡抄), which relays that the Atsuta deity (here not identified with Amaterasu) manifested in China as Yang Guifei to seduce emperor Xuanzong to distract him with a plan of invading Japan. After accomplishing this goal, she returned to her shrine.

Emperor Xuanzong wasn't exactly the conventional nemesis of Amaterasu, whether in classical mythology or in the middle ages. I'll look into the figures such a title can be applied to in in the second half of this article; due to tumblr's limits I cannot publish both halves as a single post. The bibliography will also be included in part 2.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

İsrail'in suikastıyla şehit edilen Şeyh Ahmed Yasin'in ümmete mektubu:

"Allah'ım ümmetin suskunluğunu sana şikayet ediyorum!

Ben ki kocamış bir yaşlıyım. Kurumuş iki elim ne kalem tutuyor ne de silah! Sesimle yeri inletecek güçte bir hatip de değilim!

Ben ki saçları ağarmış, ömrünün son demlerinde, türlü hastalıkların yıktığı ve üzerinde zamanın belalarının estiği biriyim!

Tek isteğim, benim gibi Müslümanların zaaf ve aczinden müteessir olanların yazmasıdır!

Siz ey Müslümanlar! Suskun ve aciz, helak olmuş ölüler! Başımıza gelen bu acı felaketler karşısında hala kalpleriniz sızlamıyor mu?

Bir halk yok mu?

Hiç mi kimse yok, Allah için ve ümmetin namusu için kızacak?

Şerefli direnişçilerken bizleri katil teröristler olarak ilan edenlere karşı duracak!

Bu ümmet utanmaz mı şerefi çiğnenirken?

Siyonist katilleri ve uluslararası işbirlikçilerini görmezden gelirken!

Omuzlarımıza el verecek ve gözyaşlarımızı silecek bir bakış!

Bu ümmetin kurumları, sivil güçleri, partileri, teşkilatları ve bariz şahsiyetleri, Allah için kızmaz mı?

Tümü birden sokaklara dökülüp, bizim için dua etmeye; "Ey Rabbimiz! Gücümüzü topla, zaafımızı gider ve mümin kullarına yardım et!" diye çağıramaz mı?

Buna da mı gücünüz yetmiyor?

Yakında bizim büyük ölümlerimizi duyacaksınız, o zaman alınlarımızda şu yazılacak:

"Bizler direndik! İleri atıldık! Kaçmadık!"

Bizimle çocuklarımız, kadınlarımız, yaşlılarımız ve gençlerimiz ölecek! Onları bu suspus ve bön ümmete yakıt yapacağız!

Bizden teslim olmamızı ve beyaz bayrak dikmemizi beklemeyin! Çünkü biz bunu yapsak da öleceğimizi biliyoruz.

Bırakın savaşçı onuruyla ölelim!

Dilerseniz bizimle olun, elinizden geldiğince öcümüzü sizden her biri boynuna taksın!

Dilerseniz bize acıyarak ölümümüzü izleyin! Temennimiz Allah'ın emaneti savsaklayan herkesten kısas almasıdır!

Umarım bizim aleyhimize olmazsınız! Allah aşkına bari aleyhimize olmayın, ey ümmetin liderleri, ey ümmetin halkları!

Allah'ım! Sana şikayette bulunuyorum! Sana şikayette bulunuyorum! Gücümün azlığını, imkanımın yetersizliğini ve insanlara karşı zaafımı sana şikayet ediyorum.

Sen mustazafların Rabbisin... Sen bizim Rabbimizsin...

Bizi kime bırakıyorsun? Bize cehennem olacak uzaklara mı? Veya düşmana mı?

Allah'ım! Akıtılan kanlar, dokunulan ırzlar, çiğnenen hürmetler, yetim bırakılan çocuklar, oğlunu yitirmiş anneler, dul kalmış kadınlar, yıkılmış evler ve ifsad edilmiş ekinler aşkına sana şikayette bulunuyorum.

Sana şikayette bulunuyorum!

Gücümüz dağıldı...

Birliğimiz bozuldu...

Yollarımız ayrıldı...

Halkımızın zaafını ve ümmetimizin bize yardım edip, düşmanı yenmedeki aczini sana şikayet ediyorum."

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

För en känsla av avsaknad är en bön, och alla böner besvaras.

Henry David Thoreau, Dagboksanteckningar 1837-1861

0 notes

Text

Mysterious Kingdom of Shambhala

Talon Abraxas

The Legend of the Mythical Land of Shambhala

The legend of Shambhala is said to date back thousands of years, and reference to the mythical land can be found in various ancient texts. The Bön scriptures speak of a closely related land called Olmolungring. Hindu texts such as Vishnu Purana mention Shambhala as the birth place of Kalki, the final incarnation of Vishnu who believers claim will usher in a new Golden Age. The Buddhist myth of Shambhala is an adaptation of the earlier Hindu myth.

However, the text in which Shambhala is first discussed extensively is the Kalachakra. The Kalachakra refers to a complex and advanced esoteric teaching and practice in Tibetan Buddhism. Shakyamuni Buddha is said to have taught the Kalachakra on request of King Suchandra of Shambhala.

As with many concepts in the Kalachakra, the idea of Shambhala is said to have outer, inner, and alternative meanings. This makes it complicated for the uninitiated to truly understand what Shambhala really is. The outer meaning understands Shambhala to exist as a physical place, although only individuals with the appropriate karma can reach it and experience it as such.

The inner and alternative meanings refer to subtler understandings of what Shambhala represents in terms of one's own body and mind (inner), and during meditative practice (alternative). These two types of symbolic explanations are generally passed on orally from teacher to student.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 lamps bon dzogchen

THE SIX LAMPS

Lamps light our way in the dark, and they illuminate themselves at the same time. The Instructions on the Six Lamps is an important dzogchen work, and is one of the root texts of the Zhang Zhung Nyengyü. This teaching describes the principals of recognizing the natural state and outlines how they may be experienced by the practitioner. This text describes Trekchö and Thögal practices as revealed by Tapihritsa to Gyerpung Nangzher Löpo. are described.

According to Bön dzogchen teachings, the suffering of sentient beings can be traced to a single cause: our failure to comprehend that internal and external appearances are only a manifestation of innate awareness. The teachings of the Six Lamps guide us to experience pure vision by recognizing the clear light of self-awareness in all levels of our being:

The lamps include: The Lamp of the Abiding Base, The Lamp of the Fleshy Heart, The Lamp of the Smooth White Channel, The Water-Lamp of the Far Reaching Lasso, The Lamp of the Direct Introduction to the Pure Realms, and The Lam of the Bardo.

the teachings of the Six Lamps and their significance in Bön dzogchen:

1. **The Lamp of the Abiding Base**: This lamp serves as the foundation of the Six Lamps. It is about recognizing the inherent, unchanging, and unconditioned nature of our mind, which is often referred to as the "abiding base" or the ground of being. By understanding this, practitioners can connect with the unaltered and pure nature of their consciousness.

2. **The Lamp of the Fleshy Heart**: This lamp centers on the heart, representing the essence of consciousness. It guides practitioners to explore the nature of mind and the heart as not separate entities but interconnected aspects of self-awareness. By realizing this unity, one can experience a profound shift in their perception and understanding.

3. **The Lamp of the Smooth White Channel**: In the context of the subtle body and energy systems, this lamp emphasizes the channels through which awareness flows. Practitioners work to purify and clear these channels, allowing for a smoother and unobstructed flow of energy and consciousness. This is integral to the practice of Thögal, where clarity and direct realization are sought.

4. **The Water-Lamp of the Far Reaching Lasso**: This lamp symbolizes the expansive and interconnected nature of awareness. It encourages practitioners to recognize that their consciousness is not confined to their physical body but extends far beyond, connecting with the entire universe. This realization brings a sense of interconnectedness and boundless compassion.

5. **The Lamp of the Direct Introduction to the Pure Realms**: This lamp guides practitioners to directly access and experience pure, transcendent states of consciousness. It involves direct introduction to the nature of mind and the recognition of the innate, luminous clarity that exists within every being. This is a step towards enlightenment and awakening.

6. **The Lamp of the Bardo**: This lamp relates to the intermediate state between death and rebirth, known as the Bardo in Tibetan Buddhism. Understanding the nature of this state is crucial for practitioners to navigate the afterlife and attain liberation. It involves recognizing the clear light of self-awareness in the transition between lives.

The core teaching of the Six Lamps is to help individuals transcend suffering by shifting their perception and understanding of reality. By recognizing the clear light of self-awareness in all aspects of existence, practitioners aim to experience a pure vision and ultimately attain enlightenment. These teachings are profound and advanced, requiring dedicated practice and guidance from experienced masters. They hold a central place in Bön dzogchen, offering a path to inner transformation and spiritual awakening.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Tasavvuf erbabından olmayan bir imamın cemaate karşı tutup 'ne o elde boncuk sallamalar, hiç olacak iş mi..' demesiyle tasavvuf erbabından bir imamın 'elin de tesbihi olmayanlar bön bön dolaşıyorlar' demesi, ikisi de İslâm'ın dili değildir . İslâm'ı anlatmanın konu sorunu yok, dil sorunu vardır."

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alr i know we all love the growly ass voice and how gender it is but fuck it can be so calming especially in The Ballad of Bull

At this point thanks to the Sabaton 24/7 Livestream I've heard just about every Sabaton song (probably) and his voice can genuinely be so fucking calming sometimes i NEED it to lull me to sleep man i am fucking insane

I have a very hard time sleeping, so any time I can't conk out on my own I will play Karolinens Bön on repeat.

I know it's not one that's necessarily calm, in fact it sounds very triumphant. But it really helps! He's just got the voice perfect for soothing somebody.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yasak sırlar 10

Umarım doğru yerden devam ediyordur.

ilk siktiğim am annemin amı hemde teyzemin evinde acayip zevkli ve heyecanlıydı, annem içime boşalma sakın peçeteye gökhan lütfen pisletme dedi tamam aanne dedim içinden çıktım içinden çıkınca annem bana doğru döndü peçeteleri alıp sikime tutunca boşalamayacığımı anladım anne gerimi gidiyor boşalıcaktım dedim annem hemen elini attı eliyle otuzbir çekmeye başladı annem neler yapıyordu böyle az önce yalvararak ikna ettiğim kadın şimdi amını bana siktirip eliyle beni boşaltmaya çalışıyordu zevk deryasında yüzüyordum resmen hadi yavrum hadi yavruşum gökhanım benimmm diyip yüzüme bakıyordu annemin altı dizlerine kadar çıplak yandan domalık vaziyette kalçalarını görünce çok değişik bi hazla peçeteye annemin ellerinde boşladım hayatımda böyle bişey yaşamamıştım annem yüzüme bakıyordu çok utanmıştım annem çok güzeldi dedim annem çenemi tutup bilmemmi oğlumm dedi gülerek hadi git banyoya peçeteyi atmayı unutma kovaya dedi pijamamı çekip yatağa oturdum anne dur dinleneyim atarım dedim annem iyi ver bana dedi yataktan inip pijamasını götüne çekip toparlanıp banyoya

tekrar geldi oğlum hadi bak Kilodunu pijamanı giy biri gelecek kızıyorum artık diye bana çıkıştı, bende tamam anne ya napayım keyfini çıkartıyorum anın annemi sikmişim birakta keyfini süreyim dedim annem böyle konuşmamdan hoşlanmıyordu, tamam sikme sokma kelimelerini kullanma rahatsız oluyorum beni günaha soktun zaten beni günahın bana annem dedim hee heee dedi odadan çıktı bende kilodumu pijamamı giyip içer geçtim annem sesizce ayaklarını uzatmış sırtınıda yaslamış tv ye bakıyordu annemm seni çok seviyorum dedim bende karşısına oturdum onu daha fazla zorlamak istemiyordum annemde bende seni çok seviyorum yavrum dedi.

annemmle sohbet etmeye başladık annem utanıyordu sorularıma kaçamak cevaplar veriyordu anne evde sikişince sevişicekmiyiz annem oğlum şu kelimeleri kullanma demedimmi ben sana diye uyardı beni tamam özür dilerim dedim hadi cevap ver dedim bakarız dedi anne hadi düzgün söyle ya dedim oğlum normal çiftler gibi yaparız işte dedi her zaman yaparmıyız anne artık hep yapıcaz dimi dedim bilmiyorum gökhan dedi anne her zaman yapalım lütfen lütfen dedim oğlum her zaman olmaz benim kocam var ev işleri var baban görür anlarsa öldürür bizi dedi gündüzleri yaparız anne babam işteyken olmazmı valla pek sana güvenemiyorum baban evdeyken orda burda beni sakın sıkıştırma bak yemin ederim amımın yüzünü göremezsin dedi annem amını yerim senin annem dedim gülerek oda yeme git teyzeninkini ye dedi trip atarak anne sana bişey sorucam sen önce teyzemi sikmeme karşı çıkmıştın ama şimdi sikersen sik diyorsun sen gece bizimi izleyeceksin doğru söyle dedim annem hahahha diye kahkaha attı izliyimmi dedi bilmem sen bilirsin izlemek istiyorsan izle istersen bizi basar gibi yap gel sende bize katıl aa daha neler dedi annem neyse kaptalım bu konuyu gelirler melirler deyip susturdu beni yarım saat sonra teyzem geldi elinde poşetler yardım ettim mutfağa aldık sohbet muhabbet öyle günü öldürdük akşam kuzenler geldi yemekler yeniyordu ben annemin yanına oturmuştum herkez yemek derdinde kuzenler kendi aleminde benim tek düşüncem annemdi masa altından bacağını ellesimmi düşünüyordum elimi yavaşça bacağına götürdüm annem elimi ittirdi oğlum doyduysan mutfağa götür tabaklarını dedi elinize sağlık deyip tabağımı mutfağa götürdüm peşimden annem geldi oğlum sen ne yapıyorsun bak yemin ederim bidaha beni rüyanda görürsün böyle bişey bidaha olursa ya biri fark etse sen sapıttın iyice dedi ben sesizce bön bön yüzüne bakıyordum.

annem çok kızmıştı içeri gittik çay faslıda bittikten sonra kuzenler kendi odalarına gittiler tek odada beraber tekli yataklarında yatıyordular iki ikişi yatamazdı yani ben kimle yatıcaksam diğeri salonda yatmak zorundaydı teyzem tülay uykunuz geldiyse serelim yatakları dedi annem olur abla dedi benim uykum yoktu ama gece olacaklara sabırsızlandığım için benimde uykum geldi dedim annem iyi madem dedi siz gidin teyze yeğen ben bardaklara su geçireyim yatarım dedi tamam aşkım dedi teyzem anneme benim içim kıpır kıpır ediyordu hadi iyi geceler annem diyip öpüp yatak odasına gittim annemle yatarken pijamamı çıkarmamıştım ama teyzeme daha iyi dayayabilmek için boxırla girdim yatağa üstüme yorganı çekip teyzemi beklemeye başladım iki dakka sonra teyzem geldi ışığı söndürmeden üstündeki v yaka kazak ile altındaki taytı çıkardı ilk defa bana teyzemi görüyordum beyaz bir ipli atlet dar altında da da siyah tayt şort gibi bişey vardı hani şu kızlar eteklerinden altı gözükmesin diye giydiklerinden teyzemi öyle görünce sikim birden Şahlandı verdi şortunun altında beyaz basenleri kalçalara kilot izinden taşıyordu ışığı kapatıp yanıma geldi iyi geceler Gökhanım teyzesinin bir tanesi deyip yanağımdan öpüp yorganın altına girdi heyecandan kalbim küt küt atıyordu 15 20 Dakika ikimizde hiçbir şey yapmadan sırt üstü yatarak tavana bakıyorduk ilk hamle teyzemden geldi bana doğru döndü elini göğsümün üzerine koydu sarılıp uyuyormuş gibi yapıyordu kalbimin atışını hissetmemesi inkansızdı bende ne olacaksa olsun dedim alttan elimin tersini teyzemin baldırına sürtmeye başladım ilk önce çok yavaş yapıyordum.

3 notes

·

View notes