#animal behaviour

Text

“The spike in aggression towards boats is a recent phenomenon, López Fernandez said. Researchers think that a traumatic event may have triggered a change in the behavior of one orca, which the rest of the population has learned to imitate.”

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Octopuses are usually solitary, but the gloomy octopus Octopus tetricus live in very high densities. Perhaps due to this living arrangement, scientists have captured footage of octopuses throwing stuff at each other, everything from silt to shells to algae. A few evidence to suggest this throwing is deliberate (not just octopus coincidentally flinging something in the direction of another octopus):

Throwing requires an unusual positioning of the siphon (think jet water propulsion device)

The things that get thrown make pretty strong contact with the receiving octopus

Throwers often exhibit uniform dark/medium colour, suggesting that these throws are linked in some way (not random throw events)

Octopus in the receiving end have been shown to try and dodge the missile

Choice of missile is often silt, and not random

Throwing is often done using a specific set of arms

Scientists think it might be some sort of communication. But it's not clear what sort, e.g. whether antagonistic or not, or is it play, enrichment etc.

#aslzoology#asl zoology#zoology articles#studyblr#octopus#marine biology#cute animals#tentacles#animals#cephalopods#nature#ocean#conservation#animal behaviour#zoology

911 notes

·

View notes

Text

@is-the-snake-video-cute I thought you'd like this

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Barncale geese and eurasian wigeons

#birds#wildlife#photography#goose#geese#barnacla#wigeon#duck#ducks#animal kingdom#bird watching#birds of the marsh#animal behaviour#a game of tones#bourgoyen#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#lensblr#original photography#pws#nature

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2013, neurobiologist Kristin Tessmar-Raible and her colleagues published some of the most compelling evidence of a molecular moon clock in an ocean creature. They studied the marine bristle worm Platynereis dumerilii, which looks like an amber centipede with tiny feathered oars running the length of its body. In the wild, the bristle worm lives on algae and rocks, spinning silk tubes for shelter. While reading studies from the 1950s and ’60s, Tessmar-Raible learned that some wild bristle worm populations achieve maximal sexual maturity just after the new moon, swimming to the ocean surface and twirling in circles in a kind of whirling dervish nuptial dance. The studies suggested that changing levels of moonlight orchestrated this mating ritual. “At first I thought this was really crazy in terms of biology,” says Tessmar-Raible, who notes that she grew up far from the ocean, “but then I started talking to colleagues in marine biology and realized that this might not be so uncommon.”

To learn more, Tessmar-Raible and her colleagues kept bristle worms in plastic boxes, feeding them spinach and fish food, and simulating typical and aberrant moon cycles with an array of standard light bulbs and LEDs. Worms raised in perpetual light or in entirely moonless day-night cycles never displayed reproductive rhythms. But worms reared with periodic nocturnal illumination synced their spawning rituals to the phases of their artificial moon. As suggested by earlier studies, Tessmar-Raible found light-sensitive neurons in the worms’ forebrains. And genetic sequencing revealed that the bristle worm has its own versions of essential molecular clock genes found in terrestrial insects and vertebrates. Tessmar-Raible’s conclusion is that the worms have a robust lunar clock analogous to the more familiar sun-synced circadian clock. “This is an endogenous oscillator,” she says. “Something in the body preserves the memory of those nocturnal illuminations.”

In similar studies, Oren Levy and his colleagues collected pieces of living corals from Heron Island reef and housed them in large outdoor aquaria, some of which were exposed to ambient sunshine and moonlight, some shaded at night to block all moonlight, and some subjected to dim artificial light from sunset to midnight and then kept in the dark until sunrise. Each day for eight days before the estimated night of mass spawning, the researchers collected bits of corals from the different aquaria and analyzed the activity of their genes. The corals in natural conditions spawned as predicted and expressed many genes only during or just before releasing their gametes. Corals subjected to artificial light and deprived of moonlight displayed anomalous gene expression and failed to release their gametes.

— The Lunar Sea

#ferris jabr#the lunar sea#science#biology#marine biology#animals#animal behaviour#genetics#astronomy#australia#heron island#great barrier reef#kristin teßmar-raible#oren levy#polychaete#platynereis dumerilii#coral#coral reefs#reefs#reproduction#moon#light#circadian rhythm

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chimpanzees and bonobos are often thought to reflect two different sides of human nature—the conflict-ready chimpanzee versus the peaceful bonobo—but a new study published in Current Biology shows that, within their own communities, male bonobos are more frequently aggressive than male chimpanzees. For both species, more aggressive males had more mating opportunities.

"Chimpanzees and bonobos use aggression in different ways for specific reasons," says anthropologist and lead author Maud Mouginot of Boston University. "The idea is not to invalidate the image of bonobos being peaceful—the idea is that there is a lot more complexity in both species."

Though previous studies have investigated aggression in bonobos and chimpanzees, this is the first study to directly compare the species' behavior using the same field methods. The researchers focused on male aggression, which is often tied to reproduction, but they note that female bonobos and chimpanzees are not passive, and their aggression warrants its own future research.

To compare bonobo and chimpanzee aggression, the team scrutinized rates of male aggression in three bonobo communities at the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve (Democratic Republic of Congo) and two chimpanzee communities at Gombe National Park (Tanzania).

continue reading

#dr congo#tanzania#primate studies#genus pan#bonobo#pan paniscus#chimpanzee#pan troglodytes#aggression#animal behaviour

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The realisation that cats sound like an Obviously Fake medieval bestiary entry or fairy legend makes for great plot ideas.

Its feet always point to the earth, even if turned upside down and tossed into the air

Its eyes shine in the dark

It can climb up a tree but not down

It imitates a baby's cry and tries to steal milk

If offended by being ignored, it causes things to fall to the floor

It can creep through any chink or crack

It will not wet its feet

It can loosen its own skin to escape being grasped

It can be trapped by placing a circle or box on an empty floor

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

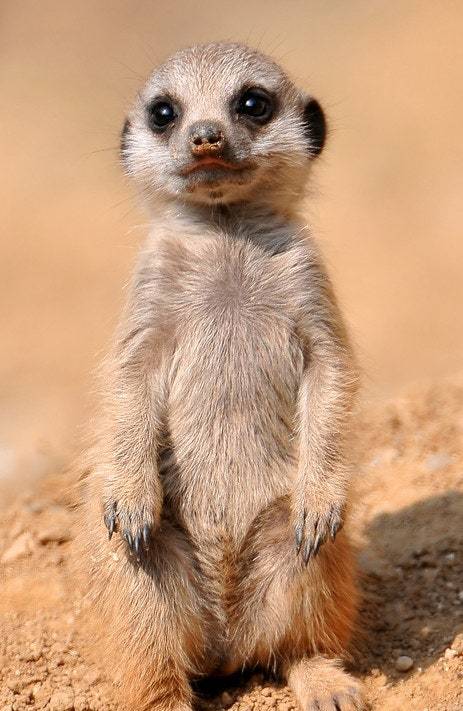

#meerkat#animals#animal#cute#wildlife#animal photography#animal science#science#mongoose#africa#south africa#cutecore#aww#awwdorable#happy things#wholesome#love#art#cute animals#animal behaviour#funny animals

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chimpanzee Mothers: Champions of Play Even in Times of Food Scarcity

ITA version here ESP version here

A recent study conducted in Kibale National Park in Uganda has revealed a surprising behavior among female chimpanzees: despite the scarcity of food, mothers continue to play with their young, playing a crucial role in the physical and social development of their offspring.

Kibale National Park is known to be the most densely populated primate forest in the world, with over 1,000 chimpanzees residing there. Researchers, led by Zarin Machanda and Kris Sabbi from Harvard University, began habituating chimpanzees to human presence in 1987, collecting detailed behavioral observations including climbing, feeding, grooming, and play.

Through the examination of 3,891 episodes of adult play recorded within the chimpanzee community of Kanyawara, researchers not only observed that this practice persists in adults unlike most other mammals, but also evaluated how adult play is influenced by diet quality. While play between adults and unrelated immatures decreased during food scarcity, play between mothers and offspring persisted, suggesting that this type of play was less constrained compared to play with other partners.

The observation that mothers continue to play with their young despite food scarcity underscores the crucial importance of play in the animal world and the extraordinary dedication of chimpanzee mothers in ensuring the well-being of their offspring, even in the most challenging times. This suggests that chimpanzee mothers play a crucial role in the physical and social development of their young, even when facing the threat of food scarcity.

That adult chimpanzees play to build relationships or support learning opportunities for younger group members evaluations of the potential functions and evolution of play are incomplete without considering its costs. The fact that chimpanzee mothers bear these costs even when ecology constrains other aspects of their social behavior primarily reveals a hidden cost of motherhood for this species, where, as with humans, mothers are important play partners for their offspring.

SOURCE

Pic Source

#Chimpanzee Mothers#Playful Parenting#Animal Behavior#Primate Research#Chimpanzee Study#Motherhood#Playtime#Kibale National Park#Uganda#Harvard Research#Chimpanzee Community#Wildlife Observations#Parental Dedication#Chimpanzee Development#Food Scarcity#Wildlife Conservation#Animal Behaviour#chimpanzee#Play#News#Drops of Science#Natural Sciences#Science

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m not sure how much of it is innate and how much of it is imitative, but a thing I’ve always found interesting about feline vocalisation is that they enunciate for emphasis in pretty much the same way that humans do, so when a cat is being emphatic you can literally hear the exclamation point.

#life#cats#animal behaviour#linguistics#note: this distinction is typically not present with kittens because kittens say everything with an exclamation point#all kitten concerns are crises of the highest order

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

Coopuccino and Americano

Any time a pigeon pair do their thing here, afterwards, they always swap positions and the female has a turn on top, like shown. I couldn't find an answer as to why or even reference to this behaviour anywhere-anyone know? Maybe pigeons are just cool like that?

#bird#birds#birblr#pigeon#pigeons#feral pigeons#feral pigeon#dove#doves#rock dove#rock doves#columbidae#all pigeons are switches i guess#animal behaviour#coopuccino

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good news: giant penis

Bad news: penis does not penetrate female during mating

Good news: sex lasts for 12 hours

Bad news: creepy researchers film and watch the whole time

#aslzoology#zoology articles#asl zoology#zoology#studyblr#bats#animal behaviour#naturecore#animals#mammals#halloween#gothic#goth

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gathering of the geese, Bourgoyen, Ghent, Belgium

#birds#geese#goose#flock#photography#wildlife#bourgoyen#ghent#belgium#patterns in nature#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#lensblr#original photography#pws#nature#landscape#a game of tones#clouds#animal behaviour#animal behavior

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite the undeniable intelligence of octopuses, and the growing evidence of their sociability, there is still the perpetual challenge of correctly interpreting their behavior—especially their behavior toward us. Octopus caretakers often emphasize that many octopuses voluntarily solicit touch, play, and companionship, even when there is no food or material reward involved. Presumably, if they did not want such interactions, they would not pursue them. But that does not erase the impossibility of knowing what another species experiences, nor does it diminish the evolutionary chasm between mammals and mollusks. When an octopus rests briefly on Craig Foster’s chest, what makes us so confident that it’s a sign of friendship? When Egbert pulls on Elora Kooistra’s finger, is he really inviting her to help?

Perhaps what we perceive as affection is actually reflexive exploration by a creature whose senses of touch and taste far surpass our own. Maybe octopuses don’t regard us so much as friends or associates as giant, elaborate levers they can manipulate for their own benefit. Though we know much more about octopuses today than even a few decades ago, they retain an essential inscrutability. There is no Rosetta Stone for octopus language, if such a language even exists. There is no familiar countenance or shared repertoire of emotion to consult. Instead, we have only a makeshift semiotics—an exchange of uncertain gestures across what may well be an unbridgeable abyss.

— Can We Really Be Friends with an Octopus?

#ferris jabr#can we really be friends with an octopus?#biology#marine biology#marine life#psychology#animals#animal behaviour#ethology#comparative psychology#octopus#octopi#craig foster#elora kooistra

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yet more benefits to being a marine biologist: we get to both keep crabs and study them

I present the world to Vincente (in Portugal, am Portuguese, Portuguese names)

This is the least problematic crab we have, just a kind soul

#marine biology#green crabs#not an invasive species for us since they are EUROPEAN#biology#crabs#animal behaviour

65 notes

·

View notes