#and my first paycheck doesn't arrive until the end of the month

Text

i'm also going to take this opportunity to shill my ko-fi again real quick! my birthday's coming up on the 15th, and if you like the stuff i make and wanted to throw a couple of bucks in the e-tip jar, there you go!

#to be clear about my financial situation: art isn't my main source of income#i just started a new job and i have savings to get me through#but i'm moving into a new unfurnished house and have had to spend a bunch on furniture and other expenses#and my first paycheck doesn't arrive until the end of the month#so i'm having to do the sensible adult thing and save as much as i can atm#but if you wanted to kick me a couple bucks for Frivolities Money it'd be greatly appreciated#it'll go towards fancy snacks and video games and stuff

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

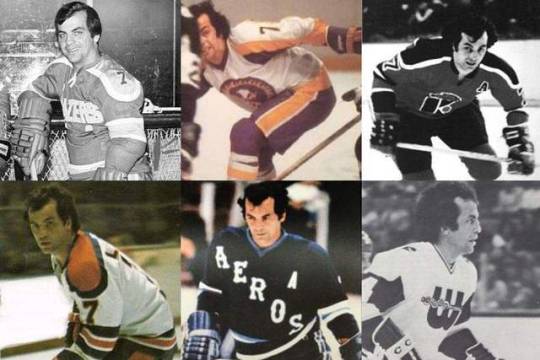

This day in hockey history, June 5th 1945, Andre Lacroix was born in Lauzon, Quebec. Lacroix is the WHA's all time leading scorer with 251 goals and 547 assists for 798 points in 551 games.

Lacroix was the last of 14 children in his family, and to this day his parents still live in the house in Lauzon, Quebec where he was born. He started playing hockey at the age of 12—late by Canadian standards—and he learned quickly to make every shot on goal count. "My father was an oil deliveryman and never made more than $75 or $80 a week," says Lacroix. "A hockey stick in those days cost one dollar, so I was always afraid to take a slap shot for fear that I might break my stick. You don't break many sticks with a wrist shot. My father used to use tape and nails to hold the sticks together so they would last for a long time."

When he was 18 Lacroix went to Peterborough, Ontario to play junior hockey, leading the Ontario Hockey Association in scoring the first year (1963) and narrowly missing the title the second. He scored 119 points the first year (45 goals and 74 assists) and 120 points the second year (40 goals and 80 assists). His career totals in 97 games were 85 goals and 154 assists for 239 points - the best of any Pete in franchise history.

In both years, he was named the league’s most outstanding player winning the Red Tilson Trophy as MVP, once beating out Bobby Orr of the Oshawa Generals.. He won the scoring race in ’65-66 playing on a line with Mickey Redmond and Danny Grant, both future NHL 50 goal scorers.

But Lacroix spoke not a word of English when he arrived in Peterborough, and he found few people in Ontario who spoke French.

"I used to hang around a bowling alley in Peterborough because the people there knew I didn't speak the language and they were very nice to me," he says. "I decided I wasn't going to sit in my room for two years and stare at the walls, so at night when I came home from practice I would write down 25 or 30 verbs in English and study them. I figured if I could learn the verbs, the rest would follow." Lacroix also lugged around a pocket dictionary, and by his second year in Peterborough he spoke passable English. His English now is impeccable, except for his use of Canada's rhetorical "eh?"

It's incredible that Lacroix went undrafted after such an outstanding junior career. So he turned pro in 1966 with the minor league Quebec Aces where he played for two seasons.

ndre Lacroix only spent one and a half seasons in Quebec, but he was so popular that he was sometimes called "the King of Quebec City." The home crowds at Le Colisée de Québec adored Lacroix's puckhandling and passing wizardry.

When the newly created Philadelphia Flyers purchased the Aces as its farm team on May 8, 1967, the club also acquired the player's NHL rights. Although Lacroix did not crack coach Keith Allen's roster at the start of the 1967-68 season, the Flyers took notice of Lacroix's play with the Aces. It would've been hard not to, as Lacroix had racked up 87 points (41 goals, 46 assists) in just 54 games. He was brought up to the NHL by the Philadelphia Flyers, a first year expansion team.

Lacroix scored on his NHL debut for the Flyers on Feb. 21, 1968, pouncing on a turnover against the Penguins and going to his backhand, one of 79 NHL goals he scored. In 18 games with Philadelphia, Lacroix had six goals and eight assists and helped the Flyers capture first place in the six-club expansion division. He followed that with 24-, 22- and 20-goal seasons for the Flyers, who were not known as the Broad St. Bullies in those days, but his playing style—finesse, not muscle—never endeared him to Philadelphia coaches.

"I know what magic Lacroix can flash with the puck," said Vic Stasiuk, who coached Lacroix in Philadelphia for one season. "The thing is, his magic doesn't work against certain clubs, particularly those that employ a tight checking game. When they do this, all too often Andrè can't play his normal game." Also, Stasiuk had a younger center on his roster named Bobby Clarke, and by the end of the 1970-71 season Lacroix was seeing only spot duty.

Two significant things happened to Lacroix while he was still playing for the Flyers. First, part of the roof of the Philadelphia Spectrum blew off in a windstorm in 1968. Then Flyers President Bill Putnam told Lacroix, "As long as I'm in this chair, you'll be with the Flyers." Brimming with confidence and feeling secure, Lacroix bought a house that year in Delaware County, Pa. and planned to settle down with his new bride Suzanne. But in a matter of months Putnam departed the Flyers' organization, somebody else sat in his chair, and Lacroix was traded to the Chicago Black Hawks at the beginning of the 1971-72 season.

"That was the start of our real-estate ventures," says Suzanne. "We decided to keep the Philadelphia house, which was a good move psychologically. My son calls it his 'blue house' because it has blue carpeting."

Lacroix spent a miserable season in Chicago, scoring only 11 points and writhing most of the season at the end of the bench. He also had to suffer the outrageous barbs of snippy Chicago Coach Billy Reay, who called the 5'8", 175-pound Lacroix "the first small French-Canadian center I've ever seen who can't skate." Quite understandably, when the WHA was born in 1972, Lacroix leaped at the opportunity to join it.

The Quebec Nordiques originally owned the WHA rights to Lacroix but traded them to the Miami Screaming Eagles, Unfortunately, the Miami franchise succumbed before it ever left the ground. Lacroix was subsequently peddled to the Philadelphia Blazers—his third team in a matter of days—and his travels were really just beginning.

Philadelphia owner Bernard Brown gave Lacroix a five-year contract at double the $30,000 he was making in Chicago and then obligingly threw in a fistful of incentive clauses with bonuses for scoring. Lacroix has always negotiated his own contracts and he has shown a remarkable sense of his market value and a shrewdness for fine-print language. By finessing the scoring bonuses from Brown, Lacroix earned himself an extra $20,000 after leading WHA scorers with 50 goals and 74 assists that first season.

"During the past six years I've signed three five-year contracts and one six-year contract," says Lacroix, "and I've never been traded in that time. I've also made it a rule that I don't sign a new contract until the old one has been settled. I've never been shortchanged a single dollar in the WHA." Moreover, as franchises collapsed all about him, Lacroix never failed to come out of the mess with a new contract for more money. Of course, it is difficult to say how many of Lacroix' teams faltered partly because they could not meet his salary.

In any case, the paycheck that Lacroix now receives from the Whalers is covered by funds from the Whalers, the league, Ray Kroc, Ronald McDonald, you name it. "To tell the truth," says Lacroix, "I don't know who pays what or where the money comes from. But every two weeks the money comes, and I don't ask questions."

Nobody was asking many questions during that first boisterous year of the WHA and, naturally, mistakes were made—and millions of dollars were lost. Says Lacroix, "I probably could have owned a franchise those first couple of years. A lot of the owners thought the way to increase attendance was to go out and hire a bunch of goons, which showed how little they really knew about hockey. The wise owners signed the Bobby Hulls and Gordie Howes, and that brought people in for a while. Now the owners are finally learning that they have to bring along the young players from the juniors."

In his own hilarious way Bernard Brown, the Philadelphia trucking magnate who owned the Blazers, was an exemplary WHA first-year owner. "The first time Brown met with our general manager," says Lacroix, "he said he wanted all of the players to report for work at nine in the morning and stay until five each night. He expected us to practice for a while, work around the building for a bit, then practice some more. All he knew was that his truck drivers worked from nine to five, and he couldn't understand why he was paying us all that money to work for two or three hours a day."

When Brown, who also had Derek Sanderson under contract for $2.7 million, lost interest in that sort of goldbricking after the 1972-73 season, he sold his team to buyers in Vancouver. Lacroix, however, became a free agent because of a clause in all his contracts that permits him to refuse to play for a Canadian team. The agreement, he says, is strictly for business convenience. At any rate, instead of going to Vancouver, Lacroix was on his way to the New York Raiders, who became the New York Golden Blades while Lacroix was en route.

The gold paint was barely dry on the blades of the Blades' skates when it became apparent there was going to be trouble. Playing in Madison Square Garden was one of the league's big goals, but when it finally happened it was a colossal bummer. "You could hear people talking all the way across the arena," recalls Suzanne Lacroix. "The Garden was great, but 4,000 people in a building that seats 17,500 was depressing."

Meanwhile, Lacroix had signed a new five-year contract with the Golden Blades, purchased a new home in West Orange, N.J. and begun filling it with furniture. By October the team was in bankruptcy court, and Lacroix had his new house up for sale.

The league abruptly moved the Golden Blades to the Philadelphia suburb of Cherry Hill, N.J., called them the New Jersey Knights and asked the players if they would use their own sticks and whatever equipment they could scrounge up until the cash-flow problems eased up. None of the Blades' uniforms, pads or sticks could be moved down from New York without running the risk of having the Knights' gate receipts, such as they were, attached by creditors. "And we were the first big league team New Jersey had ever had," says Suzanne. "At least we called ourselves big league."

"There was no dressing room in the Cherry Hill arena big enough for the visiting teams to use," recalls Lacroix, "so they had to dress at their hotels when they played us. To see Bobby Hull and Gordie Howe climbing off a bus, in the snow, with all their equipment on, made you feel 25 years behind the times."

Which, as it turned out, was right about where the New Jersey Knights were. They finished 32 games out of first place that 1973-74 season, and by the opening of the following season the team had been moved again, this time to San Diego. By the end of the Mariners'—and Lacroix'—second season, in 1976, owner Joe Schwartz was unable to meet the team payroll. For the final month of the schedule and throughout the Avco Cup playoffs the San Diego players competed without pay. "During the off-season, the league had to make up one schedule with San Diego in, one with San Diego out," says Lacroix. "No one knew if there would be a San Diego for the 1976-77 season."

Then Kroc, the McDonald's hamburger tycoon who also owns the San Diego Padres, decided that, after all, a puck looked pretty much like a Quarter-Pounder. He bought the Mariners and signed Lacroix to a new, guaranteed contract for six years and more than $1 million. Lacroix settled comfortably into the Southern California way of life, cruising around in a dune buggy and a van, and his children, Andrè Jr. and Chantal, adopted a cocker spaniel which they named Marina, after the team.

"The first two years we were in San Diego," says Lacroix, "we rented a place because we didn't know how long the team would last. But when Kroc came along, we bought a house with a Jacuzzi and a pool and started looking for schools for the kids. Eight months after I signed the papers on the house, we had to put it up for sale."

When Kroc scuttled the Mariners after the 1976-77 season, Lacroix once again went franchise shopping. "I chose Houston because the Aeros had been around for six years, and I thought that with their new building [the Summit] they would be included in any merger with the NHL. We decided to have a house built for us in Houston. So, of course, at Christmas the team almost went under. When I heard that the team might fold, I didn't even blink. My attitude was, 'So what?' I had tried to choose teams that had a good chance to stay in the league, and that obviously didn't work. So I decided that whatever was going to happen, well, let it happen."

To everyone's surprise, Kenneth Schnitzer, who owned the Summit, came to the rescue. He bought the Aeros and managed to keep them afloat for the remainder of the 1977-78 season. The family's new home was completed last March. By July, though, the Aeros had folded, and the Lacroix house, barely occupied, was up for sale.

Schnitzer eventually sold the Houston players to Winnipeg, meaning that Lacroix was once more a free agent. After consulting with his lawyer, he signed with the Whalers. "They have the most stable organization in the league, eh?" says Lacroix wryly.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Most people in America want paid leave — here's the real reason the US is the only developed nation that doesn't have it

Democrats and Republicans agree that the US needs paid leave policies for new parents.

The reason the US doesn't have one yet while the rest of the developed world does comes down to distinct cultural values.

Values and opinions are shifting in the US, so it may not be long until there is a federal leave policy.

As conventional wisdom goes, the need for paid parental leave is a polarizing an issue in the US.

It's the best way to explain why the US is the only developed nation in the world that doesn't have it.

But according to new research, most Americans actually agree that workers should get paid time off to take care of a new baby.

According to a poll from our partner, MSN, 93% of Americans agree that mothers should receive some paid leave after new babies arrive. Nationally, 85% of Americans say fathers should be entitled to paid leave, while 88% of Americans say the same for adoptive parents.

MSN polls its readers, and then uses machine learning to model how a representative sample of the US would have responded, using big data, such as the Census. It's nearly as accurate as a traditional, scientific survey.

Interestingly, whether or not parents receive paid leave is not a partisan issue.

While 96% of Democrats say mothers should get paid leave, a whopping 88% of Republicans agree. When it comes to paternity leave, things are more split — while 93% of Democrats think fathers should have it, 77% of Republicans agree. And as for adoptive parents, 94% of Democrats think they're entitled to paid leave, and 81% of Republicans concur.

More Democrats than Republicans support paid leave — but the divide isn't huge, and the majority of Republicans are on board.

So why, then, doesn't the US have a national policy. Better yet, will we ever see one?

You could certainly write a book on why the US has yet to see a federal paid leave policy — but the answers essentially come down to two distinct cultural elements at play in the US: the values we place in individualism and business.

For decades, workers in the US have subscribed to the notion of the "American Dream" — that if individuals work hard enough, they can successfully carve out their own piece of the pie.

For the longest time, these ideals have been incompatible with the idea of paying new parents to spend time off from work with their kids.

But that appears to be changing.

Not just a personal issue anymore

"Just buying formula for my baby was awful," Krystal Weston, a mother in Durham, North Carolina, told Business Insider in a previous interview.

"I hate asking people for money or putting people in a bind, but there were plenty of times where we had to ask my boyfriend's mom to help us buy formula and diapers because we also had to pay the rent."

As a dietary aide working in the kitchen of a rehabilitation center in Durham, Weston was granted 12 weeks of unpaid maternity leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993 when she had her baby, Noah, in December 2013.

Without the guarantee of paid leave while caring for her child, she was faced with the choice between economic hardship and returning to work prematurely. She chose to go without pay for almost 12 weeks to take care of him, a decision she didn't take lightly.

Noah's father and Weston's partner, Jamal Mustafa, moved in with Weston after Noah was born to help support the family. As an assistant manager at a clothing store in Durham, he brought home about $575 per paycheck. The couple's rent was $525 a month.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, new parents spend, on average, about $70 a month for baby clothes and diapers and more than $120 a month on baby food and formula. Big-ticket items like furniture and medical expenses add up quickly.

"Plenty of nights I would stay up with Jamal and budget out our bills so that we could possibly have some funds left over to save for the next month," Weston said.

Soon after becoming pregnant, Weston applied for public assistance. She was initially granted $75 a month on food stamps, which increased to about $300 a month after she gave birth to Noah, and she used this to buy household necessities and formula.

Since Weston was nursing, she qualified for The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) to receive free milk, wheat bread, eggs, and cheese. "I was appreciative of anything I could get without having to buy with real money," she said.

"If I hadn't had these assistance programs for mothers my maternity leave would have been a nightmare," she told Business Insider. "Who wants to worry about money and not knowing where their next meal is coming from?"

Weston's experience is not uncommon in the US.

According to a 2012 report from the US Department of Labor on family and medical leave, about 15% of people who were not paid or who received partial pay while on leave turned to public assistance for help. About 60% of workers who took this leave reported it was difficult making ends meet, and almost half reported they would have taken longer leave if more pay had been available.

"The US really stands alone in having a different national attitude towards time off from work," NPR political reporter and data expert Danielle Kurtzleben told WNYC's Brian Lehrer. As one political scientist told her, "'It's this idea of the American Dream — we're all kind of aspirational — the US is a kind of individualistic place.'"

"People would prefer to try to keep taxes low, let individuals be responsible for their own care, and that's sort of become the accepted value system in the US," Brad Harrington, executive director of the Boston College Center for Work & Family and a family leave expert, told the LA Times.

But this out-for-yourself attitude may be shifting.

In 2014, President Barack Obama discussed paid leave in his State of the Union Address. In 2016, for the first time in American politics, both sides of the aisle proposed plans for paid family leave policies and discussed the consequences of having no such policy. On Thursday, Trump adviser and daughter Ivanka Trump advocated for paid family leave on Capitol Hill. Google Trends also shows an uptick in Google searches for "paid leave" and "maternity leave" in the US starting in 2014.

Thanks in part to the the heightened attention paid leave has been receiving over recent years, we see that Americans are beginning to acknowledge that pulling yourself up by the bootstraps just doesn't work in this case — the American Dream does not apply here — and that it's a systemic, not just personal, issue.

We even see this playing out among millennials — arguably the most individualistic generation. Of the 18 to 29-year-olds MSN polled, 95% said mothers should receive paid leave and 93% said fathers should, too. And 27% of the people in this age group — the highest percentage of the age groups polled — said the government — i.e. taxpayers — should foot the bill.

"People are realizing that when this many people are having the exact same problem at the exact same time, we don't have an epidemic of personal failings where people simply just couldn't cobble together nonexistent access to sick days or to paid time off," Kristin Rowe-Finkbeiner, CEO of the grass-roots advocacy group MomsRising, told NPR. "We have actually a national structural problem that we can solve together."

Pro-business doesn't mean anti-paid-leave

"Historically workers have thought of themselves as potentially, eventually becoming small business owners. And well, when we all own our own businesses one day, we're not going to be hamstrung by government regulations," Kurtzleben said.

Not until businesses — and potential business owners — get on board will we see a national paid leave policy, Harrington said.

But business' attitudes are shifting, and we're seeing that paid leave isn't the small business killer it was once said to be.

In 2015, 12% of private sector workers had access to paid family leave through their employers. Now we're up to 14%. In the span of just a few years, the US has seen numerous private sector companies expand their parental leave offerings.

On the state level, the US now boasts five states and the District of Columbia — up from just three states in 2015 — that offer or will offer paid family leave programs.

In New Jersey, where employees and employers contribute a small amount from each paycheck to an insurance fund, the program is overwhelmingly considered a success and a far cry from the business-killer these programs are often feared to be.

A study from the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers University found that women who had taken advantage of New Jersey's paid-family-leave policy were far more likely than mothers who hadn't to be working nine to 12 months after the birth of their child.

The study also found these women to be 39% less likely to receive public assistance and 40% less likely to receive food stamps in the year following a child's birth compared to those who didn't take any leave.

And in Washington state, for the first time in US history, we saw businesses work with lawmakers to develop a state-wide leave policy.

While many businesses and pro-business lobbyists are far from getting on board, we're seeing the needle move.

With the FAMILY act before Congress, the Trump administration's support of a paid leave policy, and Americans' overwhelming support of paid leave policies, the pieces all appear to be in place — it's just a matter of time before the US catches up to the rest of the world.

SEE ALSO: The science behind why paid parental leave is good for everyone

DON'T MISS: 'I didn't feel appreciated' — inside the 'backwards' reality of taking unpaid maternity leave in America

Join the conversation about this story »

NOW WATCH: A CEO spent $6 million to close the gender pay gap at his company

0 notes