#and like these are fictional nonhuman characters with no tied race

Note

Obligatory, your character can be trans, there’s a trans character in the game, the goblins are a fictional race, there is no ties to any real world race other than what you made up. Jk gets paid pennies on top of her already inflated billions through royalties, she wasn’t even a part of the game, she’s a scumbag, but attacking innocent people for playing a video game isn’t helping your cause.

Have you never heard of allegories in fantasy? If not, here's a pertinent example: JKR openly stated werewolves (a fictional species) are an allegory for people living with HIV/AIDS. Werewolves are not real, but are specifically tied to a group of people who actually exist.

Something else to consider: a lot of people don't consider Jews human, and find it very easy to either compare us to a mythical race or to accuse us of literally being a nonhuman species. Look at dual seed (also called second or serpent seed) theory, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion being the basis of Icke's reptilian conspiracy, the belief (less popular today but still brought up regularly) that Jews have horns, the superstitions about us being able to curse people, and—for extra credit—the various antisemitic tropes that accuse us of nonhuman behaviour without alleging that we're a nonhuman species. (If you don't know where to start with that last one, check out the Wittenberg Judensau which Luther used as cover art for his book about how Jews worship the Devil.) These are things many antisemites use as allegories for their beliefs, while others believe these things to be literally true.

Regarding the ones who use fiction, particularly mythical beings, as a symbol of their antisemitism: I've encountered neo-Nazi forums where members explicitly suggest to one another that they should use Skeksis (a fantasy race from the Dark Crystal franchise) as code for Jews so people won't immediately know what they mean. Here's another example of people discussing the possible use of Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance as a rallying point to encourage people to see the "truth" that Jews engage in blood libel and general behind-the-scenes manipulation of power. There was also a nasty incident when Maya Rudolph and Andy Samberg announced their Christmas-themed show Baking It! and the official YouTube channel had to turn comments off because people who were angry about two Jews celebrating Christmas started posting antisemitic quotes with the word "Jew" swapped out for "elf". They didn't literally believe Jews are elves, but they seized the opportunity to use a fantasy race as a metaphor for Jews when it suited them (even though Christmas elves are more frequently equated with Sámi). I've included screenshots of that below the cut.

Point is, many aspects of real Jewish history as well as popular anti-Jewish myths have strong parallels in the Potterverse goblins. The vast majority of these things were not a part of goblin folklore prior to the 20th century, so the "that's just what they're like in traditional mythology!" doesn't hold water. I genuinely believe the parallels in the books were unconscious on JKR's part, being a product of the insidious saturation of antisemitism in our society, but the film franchise expanded on it and added additional features (e.g. long noses, something never mentioned in the books), and now this game is adding even more. Hogwarts Legacy's plot and design normalises antisemitic narratives and visual motifs, and if any neo-Nazis are looking for a new dogwhistle, they'll have plenty to work with here.

You can easily write fantasy without doing this shit. Hell, you can even write about goblins stealing babies without doing this shit! It's not some massive insurmountable task to exclude antisemitism from your work. Together, Moira Squier, Adrian Ropp, Adam Koford and Shane Lewis formed a team of experienced writers who should have more than enough talent to come up with something other than On the Jews And Their Lies 2.0 for a backstory.

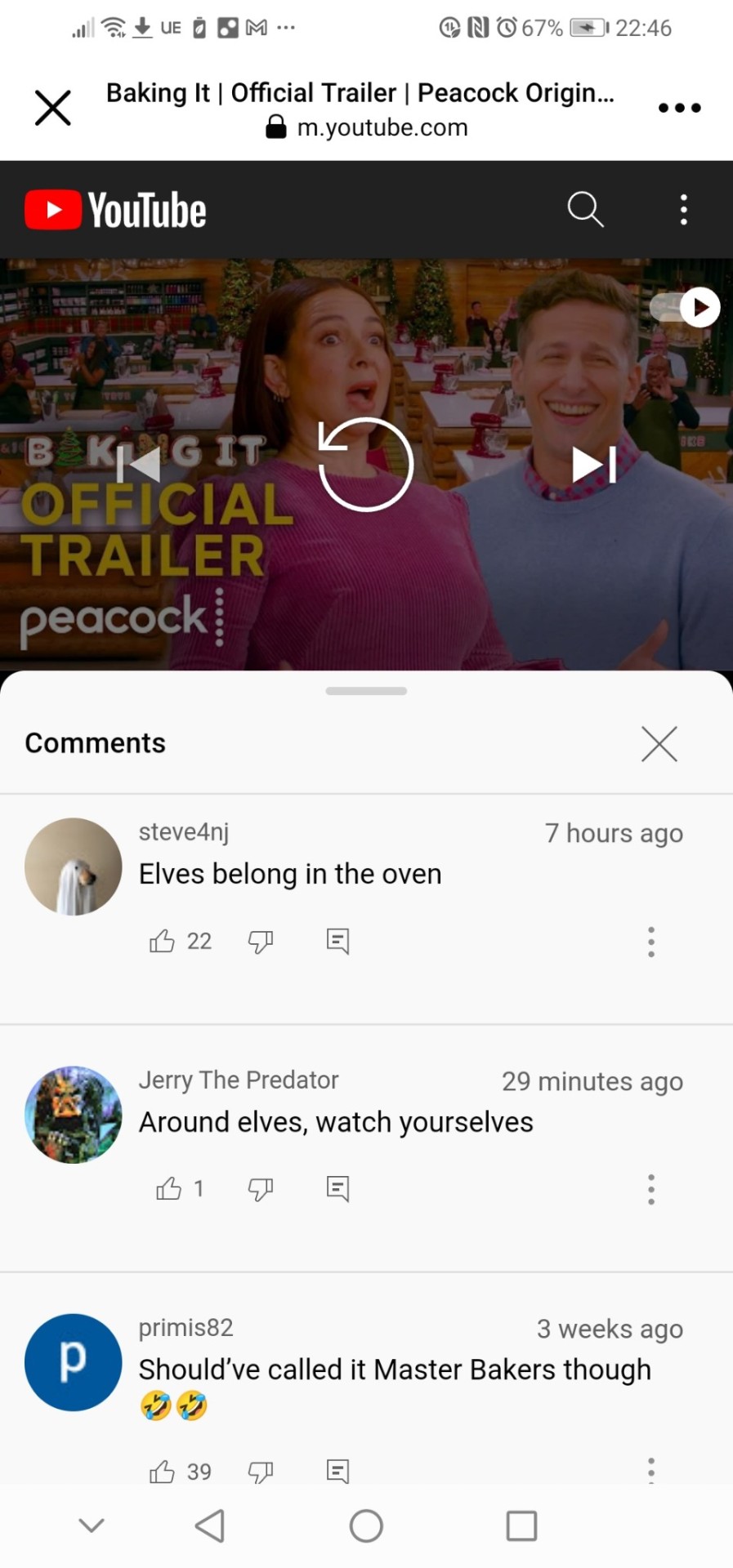

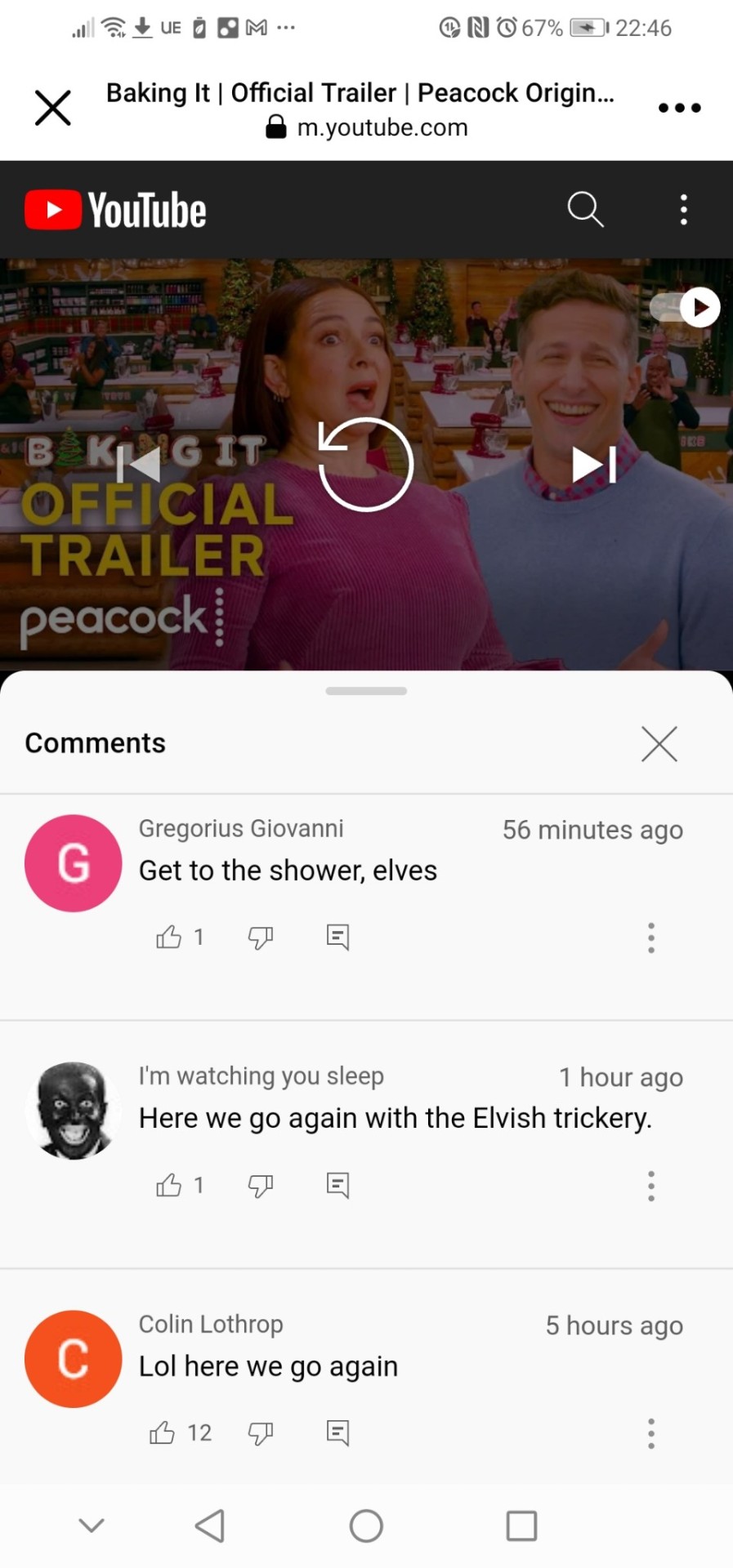

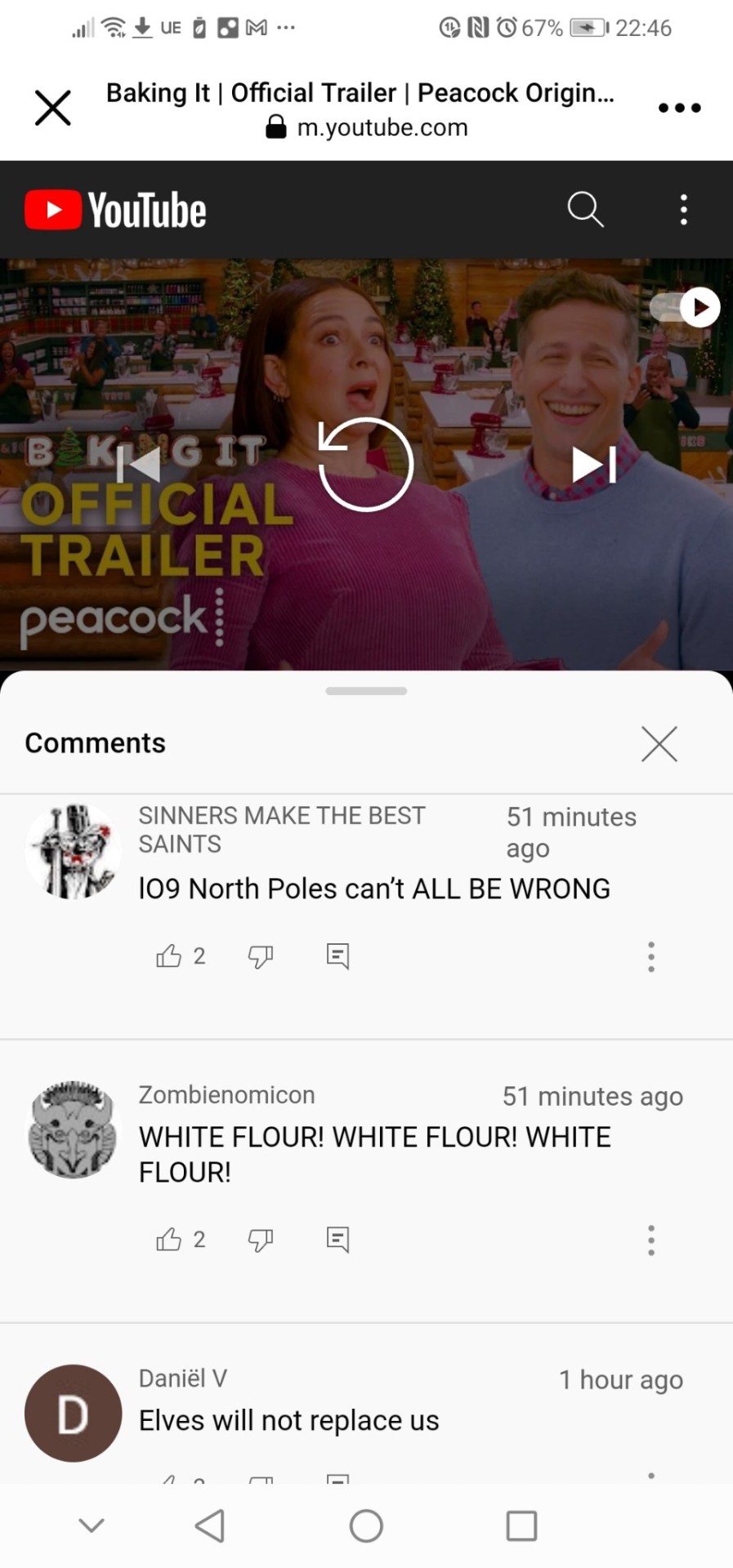

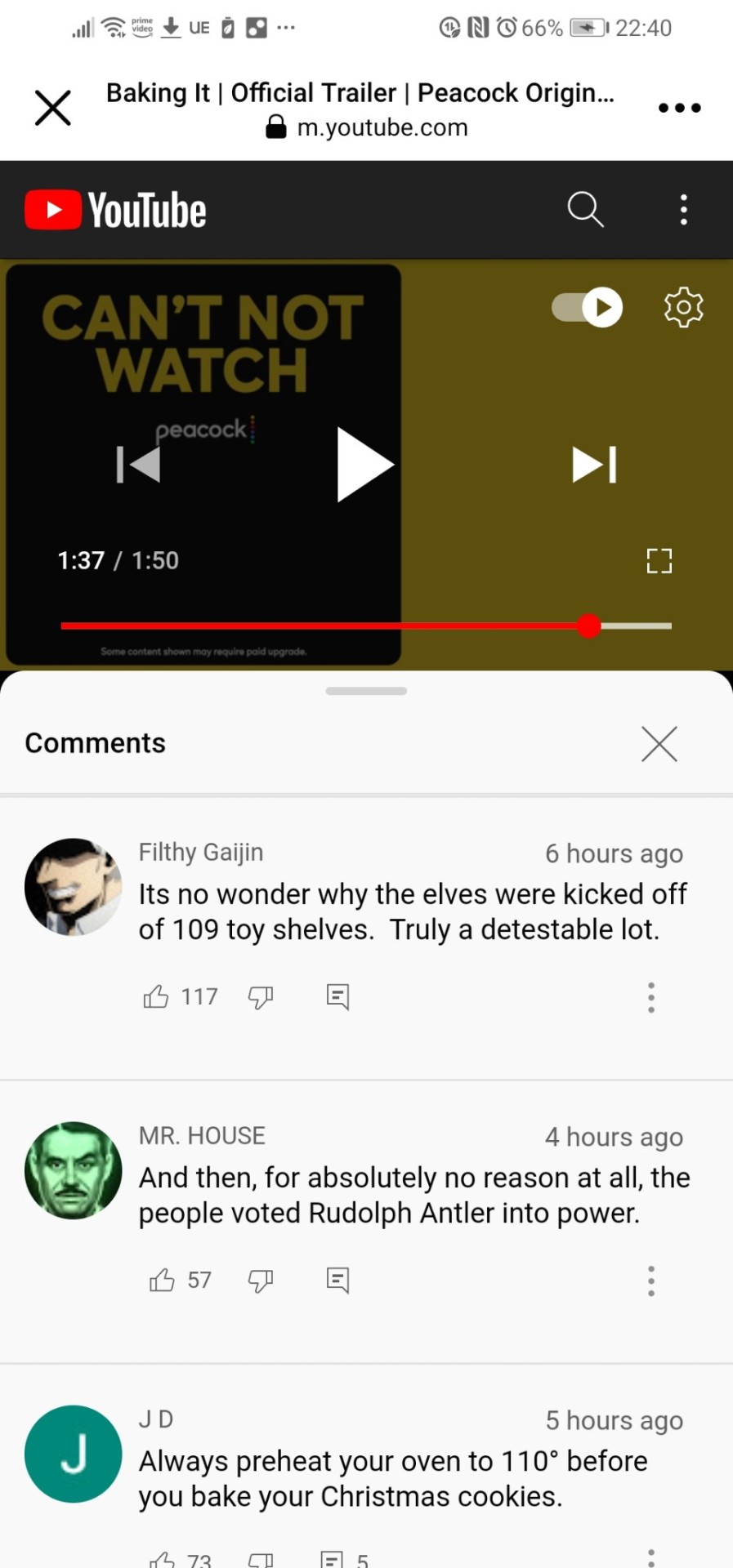

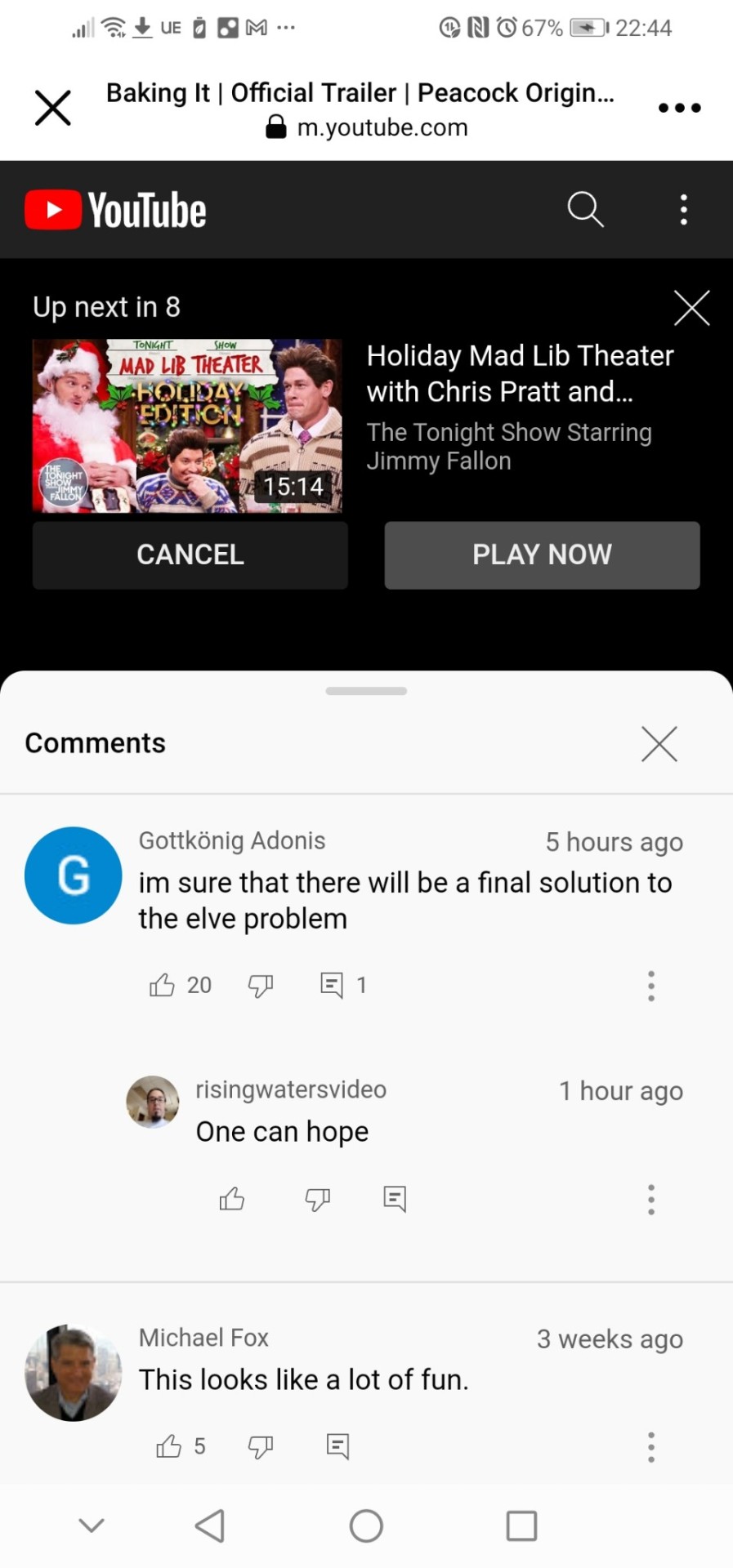

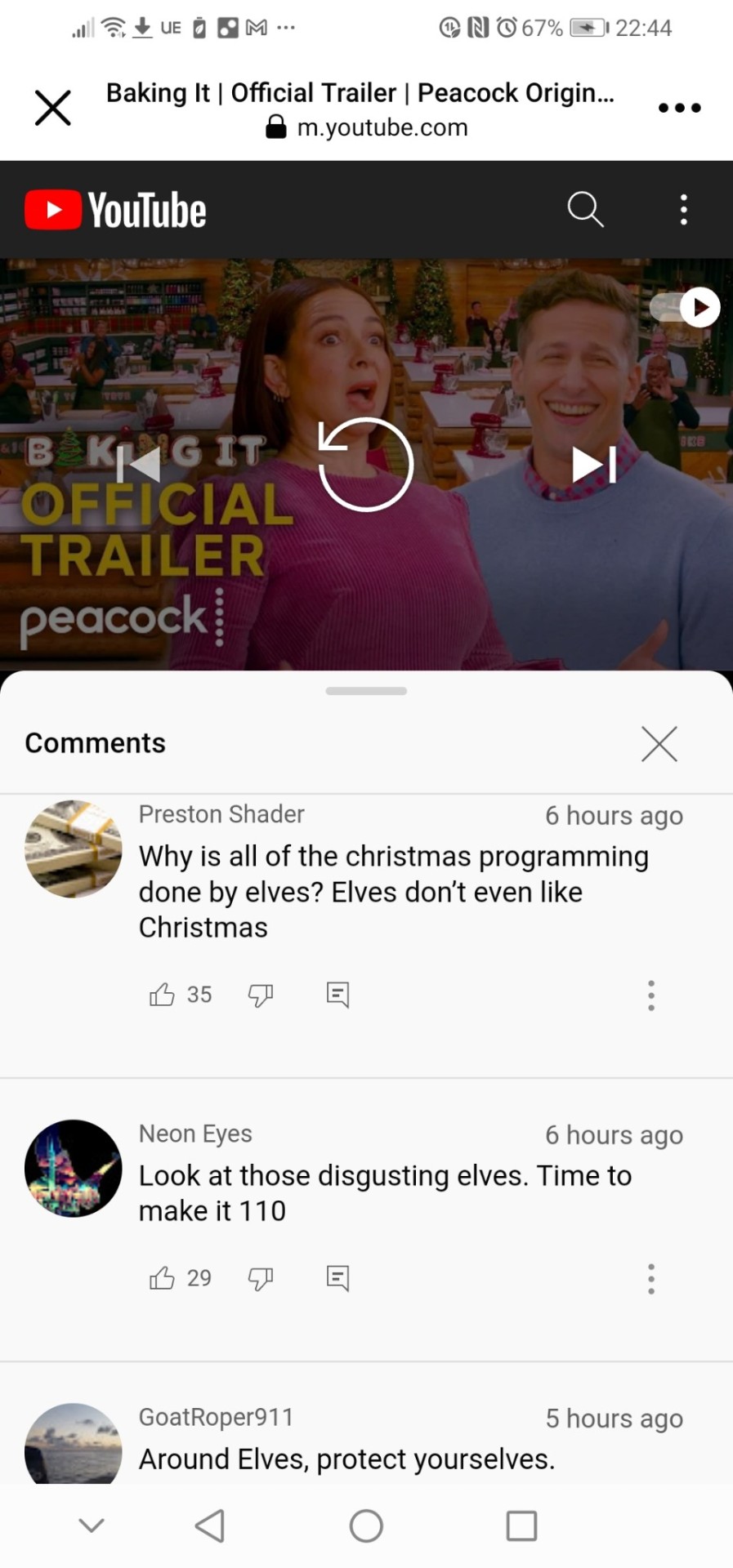

As promised, here are some of the comments left on the Baking It! trailer before they were turned off:

If you don't recognise the dogwhistles here, look up 109/"make it 110", "the Jewish problem" and "Jews will not replace us"; also consider why people reference showers or ovens apropos of nothing.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

It suddenly occurs to me that, while “woke” rhetoric gives cover to the unimaginative, stultifyingly dull people that just want fantasy races to be reskinned humans, that isn’t the actual motivation of the idea, for most of them. Know what is?

They’re fucking furries.

Furries are the people who cannot conceive of a nonhuman character other than as an alternative persona for their own pedestrian suburban piece-of-shit selves. Furries are the ones who think “Sure I could have uplifted animals in my science fiction webcomic with language and culture reflecting the anatomy and behavior of the animals in question—but I’d rather just blithely say a 25th-century talking fox is Jewish, and have the story be about his gay romance!”

(I just saw art purporting to be a fucking yuan-ti, dressed like a 1980s office worker and drinking tea. With lips. And her eyes half-lidded. And yes, she was the snake-headed caste. I think there are some things about how snakes’ faces work that you don’t understand, there, buddy. As well as, y’ know, what the yuan-ti are like?)

#that's it fire the halo rings#consciousness was a mistake#berserk button#salty fantasy writer#i was trying to think of an animal whose wang makes a bris more complicated and i GUESS canids are weird enough

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

TerraMythos 2021 Reading Challenge - Book 12 of 26

Title: A Wizard of Earthsea (Earthsea Cycle #1) (1968)

Author: Ursula K. Le Guin

Genre/Tags: Fantasy, Young Adult, Third-Person

Rating: 8/10

Date Began: 5/6/2021

Date Finished: 5/12/2021

Ged is a talented young magician with incredible potential-- possibly greater than any before him. He sets off to join the wizarding School of Roke, and quickly surpasses all of his peers. But in an act of arrogance, Ged tries to bring back the dead to impress a rival student. He unleashes a malevolent shadow upon the world, leaving him traumatized and permanently scarred.

Soon Ged finds himself hunted by the shadow wherever he goes. None of his magic seems to work on it. Worse, he lives in fear that if the dark creature overtakes him, it will use his body as a weapon to harm others. Ged journeys from island to island in an attempt to find the solution and banish the shadow once and for all.

Only in silence the word,

only in dark the light,

only in dying life:

bright the hawk’s flight

on the empty sky.

Content warnings and some spoilers below the cut.

Content warnings for the book: Violence and death, including child death and animal death. Traumatic injury.

As a fiction writer, Ursula K. Le Guin is best known for her Earthsea series, but I haven’t read them until now. She had a big impact on my childhood via a series of picture books called Catwings (they're... about a family of cats who can fly). As an adult, I’ve grown more intrigued as I've learned about Le Guin’s philosophies, especially anticapitalism. I read her famous horror story The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas last year and found it unsettling and thought-provoking. So I decided to read some of her longer works! And, of course, speculative fiction is always the way to my heart. My wonderful sister gave me the first four books of Earthsea for the holidays last year, and I’m finally getting the chance to read them.

Overall I had a good time with A Wizard of Earthsea. It’s structured differently than a lot of fantasy novels I’ve read. While there is a big overarching plot, the individual chapters usually have their own complete story arc. It’s the type of book where you can read one chapter before bed and feel like you got a whole story; each part advances the main narrative while also providing a complete side adventure.

There’s a lot of travel in A Wizard of Earthsea due to the setting. Earthsea is a giant, possibly world-spanning archipelago, meaning there’s a ton of islands, each of which has its own way of life. The conflict naturally has Ged travel from island to island and interact with various peoples and creatures. The closest comparison I can think of is The Odyssey, and I’d be shocked if Le Guin didn’t draw inspiration from that. Both stories involve the protagonist traveling by sea and meeting a variety of characters and mythological creatures through smaller, discrete conflicts and interactions. Usually I find long travel sequences boring, but in this case they were one of my favorite parts of the book. There’s always a sense of anticipation on where Ged’s journey will take him next.

The magic system is also is pretty cool. The idea is that all parts of nature, from humans to goats to oceans, have hidden “true” names. Knowing something (or someone’s) true name gives one power over it (or them). Thus wizards use true names to manipulate nature; giving another person your true name is an act of absolute trust and devotion. However, a big theme of the book is equilibrium. One must always be aware of potential consequences when using magic. Changing the wind in one part of the world could cause a devastating storm one island over. Sort of a butterfly effect type thing.

Even though violence is one of my content warnings, I’m impressed that Le Guin largely circumvents it in the story. In many fantasy stories, a wizard/mage character uses their magic to fight and crush their foes. Not so much in this novel. While Ged clashes with various entities through the story, he usually just outsmarts them. Thus his showdown with a big, fuck-off dragon boils down to Ged guessing its true name and telling it to leave. Antagonists are usually the ones instigating violence.

One thing I found odd about the pacing of the book is it slowed down a lot in the last few chapters. There’s a big action sequence with serious consequences around the novel’s midpoint, but everything after that is slower and more reflective. On a surface reading level, I’m not sure I liked this. I’m used to stories ramping up the tension more and more until the end. However, I did like the climax itself, when Ged reveals the shadow’s true name. The central moral of the novel is that one needs to accept everything about themselves, including their past mistakes. Everyone has a dark side, which ties into the central theme of balance, and even the opening poem of the novel (which I used as the excerpt for this review). It’s a pretty universal idea, but Le Guin presents it in a thematically satisfying way.

I tagged this as a Young Adult novel because Le Guin wrote it for a teenage audience. YA didn’t exist as its own genre at the time, but A Wizard of Earthsea is a coming of age story (a staple of YA), and even has a moral message of sorts at the end. However, sometimes it’s really obvious that it’s intended for a younger audience. As I get older, I’ve noticed that YA tends to be pretty blunt about its meaning and symbolism in a way adult novels aren’t. For example, while pursuing the shadow, Ged gets lost in a mysterious fogbank. To me this was a clear callback to the first chapter, where Ged outsmarts a band of barbarians by trapping them in a fog. But Le Guin also made sure to tell me several pages later, in case I missed the parallel. I’m torn on this when reading YA. While I’m not the intended audience, I feel this approach underestimates teenagers’ ability to critically examine a text. But YA teaches many how to view things that way, so I see why authors do it. Teens aren’t a monolith, but it is interesting to see this tendency to over-explain in a novel from 50+ years ago.

A Wizard of Earthsea is surprisingly progressive in many respects. Perhaps the most obvious is race. Ged and most of the main cast are explicitly nonwhite and described as such in the text. This isn’t a huge revelation in 2021, but it’s amazing to see something like that in a mainstream fantasy novel from 1968. Apparently Le Guin struggled with publishers for a long time, as many early covers whitewashed Ged for the sake of “sales” until she gained more creative control. And the (shitty) film/TV adaptations of Earthsea are just as guilty. I went through a LOT of covers while researching this book, and even newer editions often opt for heavily stylized art, nonhuman subjects, etc. The cover I chose is from 1984, when Le Guin presumably had more influence on Ged’s portrayal. I’m interested to see how past book covers stack up when I deep dive on the other books.

However, I found the book to be not so progressive when it came to gender roles (I know, I wasn’t expecting that either). Le Guin makes it very clear that all the famous and powerful wizards/mages in Earthsea are dudes. The wizard school toward the beginning is all dudes. All the adventurers and sailors in the story are dudes. Ged himself makes some pretty sexist comments (though to be fair, that was pre-character development). There are relatively few female characters in the story, and many are either bit parts or (in one case) a seductive, power-hungry villain. Portraying sexism in a fantasy setting isn’t an inherently bad thing. Jemisin’s Dreamblood duology, which I read earlier this year, introduced stringent gender roles in order to explore the insidious nature of misogyny. But A Wizard of Earthsea doesn’t really go beneath the surface level. Yarrow is probably the most well-written female character in the story, and she only shows up in the last few chapters. Again, I’m interested to see how Le Guin handles this in later entries; the next book stars a female protagonist and Ged’s the deuteragonist.

I liked A Wizard of Earthsea overall, and I think it serves as a good introduction to both the series and a central recurring character. While I have some criticisms of the first book, I do realize it’s a relatively early work of Le Guin’s. The last novel in this series was published in 2001, so I’m interested to see how the characters and writing changed over 30+ years.

9 notes

·

View notes