#ancient women

Text

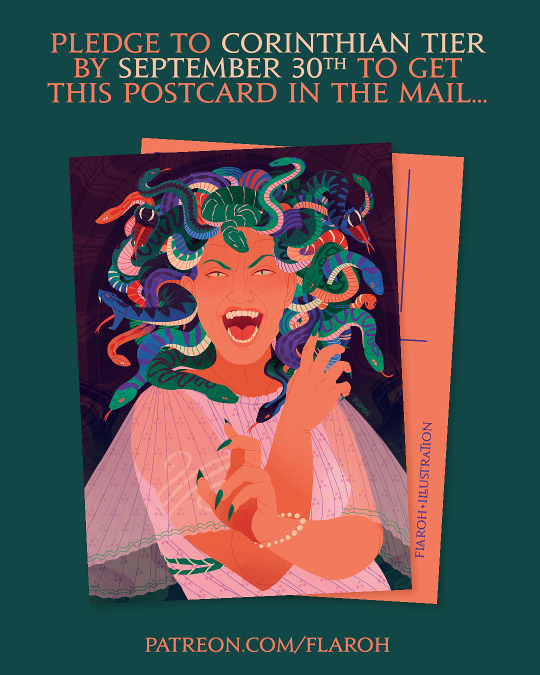

Medusa 🐍🧡🌿

I absolutely loved creating this portrait! It's a companion piece to my Medea and Hekate portraits. Medusa has become very popular in modern myth reception, especially as a #MeToo symbol and feminist figure. She's the embodiment of feminine rage, and many contemporary depictions of her have her mid-scream, baring her teeth, reminiscent of her original apotropaic gorgon form.

In this illo I wanted Medusa's expression to be more of a powerful roar/laugh, rather than a futile wail. However, I've kept her body language defensive, like she wants to lash out with those talons (a bit of an anachronistic addition I admit), but she's also trying to protect herself.

Finally, in all these depictions I've stuck to a homogenous mass of green snakes for her hair. But this time I wanted something more fantastical and colourful. None of these snakes look like any real species, but I drew heavily from vipers, adders, rattlesnakes, and even some non-venomous species like constrictors and garter snakes :)

Patrons will be receiving A6 prints, as well as an Arachne sticker 🧡 If you'd like your own, sign up by the end of the month!

#medusa#tagamemnon#flaroh illustration#ancient history#ancient women#greek myth#art history#greek mythology#arachne

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of Cleopatra by Hans Makart (1875–1876)

#art#art history#art painting#painting#oil on canvas#historical art#historical painting#old art#19th century#19th century art#hans makart#austrian art#austrian artist#women in art#ancient women#cleopatra

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Signal by John William Godward

#john william godward#art#antiquity#neo classicism#neo classical#neo classicist#ancient world#ancient women#dress#history#europe#european#ancient#classical#marble#architecture#sea#mediterranean#lady#woman#architectural#ancient rome#women#dresses#landscape#roman

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.archaeology.org/issues/552-2405/digs/12301-dd-egypt-luxor-women-stela

Interesting article on the appearance of women in Egyptian art, specifically on stelae.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fresco detail.

Vila Arianna, Castellammare di Stabia.

#villa ariana#Castellammare di Stabia#ancient art#fresco#ancient roman#ancient rome#original photography#ancientprettythings#birds#women#men#ancient men#ancient women#ancient decoration#onetinydetail

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Jezebel#Jezabel#jezabel#history#jezebel#history of women#ancient women#women in the bible#women in history#History of bible#Holy bible#Priestess of baal#priestess#Book of Kings#Queen#my favorite

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ovid’s women reflect a society that follows a code of conduct that exists in parallel and in tension with Augustan legislation. There is a significant gap between the law’s desire to control female sexuality and the social realities of women who refused to be labelled as either matrons or prostitutes. Ovid’s Ars revels in this gap.

Law and Love in Ovid: Courting Justice in the Age of Augustus, Ioannis Ziogas

#Ovid#Ars amatoria#Ioannis Ziogas#Roman literature#classics#tagamemnon#Augustus#ancient gender and sexuality#ancient women

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sleeping Lady, Hypogeum Hal-Saflieni, Malta (2500 BCE)

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine an ancient council of Greco-Roman women. That's what we have here.

by Midjourney v5

EDIT:

Here's the prompt I used:

In a great spacious round and well-lit Greco-Roman temple chamber with ample lighting, close-up of numerous women in ancient Greek clothes with fine up-do hair are seated on marble benches around a heavy marble circular table, heated debate, marble mosaic, balanced classical architecture, mythical, ethereal, intricate, elaborate, hyperrealism, hyper detailed, strong expressiveness and emotionality, in the style of Alma-Tadema, Norman Rockwell, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Henryk Siemiradzki, Edwin Long, cinematic lighting, visual clarity, 200mm, UHD, 32k, 16k, 8k, 3D shading, Tone Mapping, Ray Tracing Global Illumination, Diffraction Grating, Crystalline, Lumen Reflections, Super-Resolution, gigapixel, color grading, retouch, enhanced, PBR, Blender, V-ray, Procreate, zBrush, Unreal Engine 5, Cinema 4D, ROMM RGB, Adobe After Effects, 3DCG, VFX, SFX, FXAA, SSAO, --ar 4800:2400

#AI Art#Midjourney#Midjourney v5#Ancient Greece#Ancient Rome#Greco-Roman#boulé#ancient women#Midjourney prompt

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spartan Social Structure: Part Three – Spartan Women

It may seem strange to remove Spartan women into a social grouping of their own – they were, after all, of Spartan blood too; however, their existence was so entirely separate to the homoioi, that there’s really no other way to approach them.

They might usefully be viewed as second class citizens – though I must emphasise I use this term in no way to suggest a value judgement upon them, or that this should be taken to mean that they weren’t respected by the men around them; I speak only in the sense of a patriarchal, hierarchical structure which absolutely placed the homoioi above every other Lakedaimonian.

Modern scholarship around this particular topic is vexed by interpretations reached via a modern feminist lens, with the result that we very often find an entirely skewed view of Spartan women as liberated (in the modern sense), free to do as they pleased, going so far as to support the notion that Sparta was, ultimately, a secret gynocracy.

For example, and summing up this view, Christensen quotes Simone de Beauvoir, who wrote that, in Sparta women:

"… underwent the burdens of maternity as men did war: but except for this civic duty, no restraints were put on their freedom."

I have tried here to give a more balanced view of historical probabilities by focusing on the primary sources rather than modern perspectives; consequently, I’ve used a lot more direct quotes than usual.

The Privileged Women of Sparta

When academics speak of the privileges accorded Spartan women, they are usually referring to comparisons with Athenian women, and by that yardstick, Spartan women did enjoy certain privileges; most notably, the ability to own property and to participate in physical exercise. Cartledge even suggests that they were granted an education in parallel to the agoge, though this is pure speculation, and Ducat resoundingly states his opinion that it’s nonsense.

We can be fairly certain, though, that girls did receive some form of education, even if it wasn’t in line with the agoge. They were raised at home with their mothers, but perhaps had a system of mentorship on the same pattern as the agoge, if Plutarch is to be believed:

‘Sexual [pederastic] relationships… were so highly regarded that respectable women would in fact have love affairs with unmarried girls.’ [Lyk 18]

They played some sports as you will see below – though which sports, whether with the boys, whether naked or in short tunics, are all controversial, realistically unanswerable questions – and they participated in sacred dancing and footraces on behalf of various gods.

Perhaps we might view their girlhood as being blessed with some form of freedom which their Athenian counterparts didn’t enjoy; but this probably ceased at marriage, which occurred between 18 and 20.

But before we get into that…

What did the Ancients say to Make us Think Liberation was Even a Possibility?

More than usual, it’s super important to remember that our sources were written by cultural outsiders, who acted from a variety of motivations:

1. To reinforce the social norms of their own city-states, particularly around the need for monogamy and social control of ‘their’ women by means of using ‘Spartan women as a cautionary tale’;

2. For comic or dramatic effect;

3. In defence of Lykourgos’ Laws.

The possible exception to all these men being outsiders is Xenophon, who (we believe) sent his two sons through the agoge during the 4th Century BCE, and perhaps had some first-hand experience of the Spartans at home – but that is by no means certain.

Plutarch, for example, in his Sayings of Spartan Women, reports the young royal girl, Gorgo (future wife of the famous King Leonidas), speaking up when invited to do so by her father, King Kleomenes:

‘When the Milesian Aristagoras was urging Kleomenes to make war against the Great King in support of the Ionians and was promising him quantities of money, and also adding more to meet his objections, the king’s daughter Gorgo said, ‘Father, this miserable little foreigner will ruin you completely unless you drive him out of the house pretty quickly.’ [Sayings of Spartan Women, Gor. 1]’

Kleomenes took her advice, and this story is often held up as an example of feminine empowerment; however, what Plutarch doesn’t include from the original story in Herodotus, is that the historian had already told the reader that Kleomenes ‘was not quite right in the head, to the extent that he was almost a lunatic’ [His. 5.42].

Aristotle, in his Politics, claimed that Spartan women enjoyed such total freedom that they defeated even Lykourgos, the Lawgiver himself, in his attempt to curb them:

‘…it is said that Lycurgus did attempt to bring them under the laws, but since they resisted, he gave it up.’

He claims that, unburdened by constraint, they lived totally at their ease:

‘…And this has taken place in [Sparta], for the lawgiver wishing the whole city to be of strong character displays his intention clearly in relation to the men, but in the case of the women has entirely neglected the matter; for they live dissolutely in respect of every sort of dissoluteness, and luxuriously.’

It is on his say-so that anyone believes that Sparta may have been a gynocracy:

‘…in the time of their empire, many things were controlled by the women; yet what difference does it make whether the women rule, or the rulers are ruled by the women? The result is the same.’

[Selections taken from Politics, 1269b-70a].

From quite a different source, and a contemporary, Classical one, Euripides in his play Andromache, has Peleus complain about the sexual license of Spartan women:

They leave their houses in the company of young men, with bare thighs and loosened tunics, and in a fashion I cannot stand, they share the same running-tracks [dromoi] and wrestling places [palaistrai] with them. After that, is it any wonder that you do not bring up women to be chaste?

[Andr. 597–601, trans. D. Kovacs.]

Aristophanes, in his comedy Lysistrata, gives the Spartan woman Lampito a forward, vigorous character, in line with this idea of their immodesty:

LYSISTRATA

Welcome Lampito!/Dear Spartan girl with a delightful face,/Washed with the rosy spring, how fresh you look/In the easy stride of your sleek slenderness,/Why you could strangle a bull!

LAMPITO

I think I could./It's from exercise and kicking high behind.

LYSISTRATA

What lovely breasts you have!

LAMPITO

Feel them for yourself with your tender fingers... /I feel as though I’m an altar-victim.

[I’ve taken the liberty of translating the Scotch dialect the original translator irritatingly gave Lampito.]

Xenophon in On Spartan Society, supports these claims only so far as to say that:

‘In Lycurgus' view, by contrast, clothes could be produced quite adequately by slave women, whereas in his opinion the production of children was the most important duty of free women.

So in the first place he required the female sex to take physical exercise just as much as males; next he arranged for women also, just like men, to have contests of speed and strength with one another, in the belief that when both parents are strong, their children are born sturdier.’

Being freed from sedentary activities and participating in sporting or group activities can give girls a feeling of control over their lives, provided they enjoy it; however, this is to overlook the fact that there were almost certainly those who didn’t enjoy sport and would’ve preferred to weave. They had no choice whether they participated or not.

Plutarch gives us the fullest picture, though I place his information last because, as I’ve mentioned elsewhere, he was writing more than 500 years after the Classical period, and through a Roman-era lens and we don’t know how reliable his sources were. He should always be taken with caution.

‘First, [Lykourgos] toughened the girls physically by making them run and wrestle and throw the discus and javelin. Thereby their children in utero would make a strong start in strong bodies and would develop better, while the women themselves would also bear their pregnancies with vigour and meet the challenge of childbirth in a successful, relaxed way.

He did away with prudery, sheltered upbringing and effeminacy of any kind. He made young girls no less than young men grow used to walking nude in processions, as well as to dancing and singing at certain festivals with the young men present and looking on.

On some occasions the girls would make fun of each of the young men, helpfully criticizing their mistakes. On other occasions they would rehearse in song the praises which they’d composed about those meriting them, so that they filled the youngsters with a great sense of ambition and rivalry. For the one who was praised for his manliness and became a celebrated figure to the girls went off priding himself on their compliments; whereas the jibes of their playful humour were no less cutting than warnings of a serious type, especially as the kings and the gerontes attended the spectacle along with the rest of the citizens.

There was nothing disreputable about the girls' nudity. It was altogether modest, and there was no hint of immorality. Instead, it encouraged simple habits and an enthusiasm for physical fitness, as well as giving the female sex a taste of masculine gallantry, since it too was granted equal participation in both excellence and ambition. As a result, the women came to talk as well as to think in the way that Leonidas' wife Gorgo is said to have done. For when some woman, evidently a foreigner, said to her: 'You Lakedaimonian women are the only ones who can rule men,' she replied, "That's because we are the only ones who give birth to men.'

[From Lyk 14]

But Were They Really Liberated?

Liberation necessarily requires the ability to choose one’s own path through life – whether to work or make a home, the ability to take part in the political system, whether to marry or not and who, and most importantly, to have full bodily autonomy. I’ll try to address each of these points below.

Women’s Work

There’s no evidence that Spartan women did any kind of manual labour – the helots are attested doing everything from nursing babies to weaving and everything in between. The only task, beyond the requirement to produce children, which Spartan women are attested doing, is whatever we might understand ‘managing a household’ involved.

I can’t imagine there was a great deal to do, beyond managing the helots themselves and perhaps taking care of any religious obligations, and it’s worth mentioning here that it’s highly likely that households were multi-generational. A newly married couple probably lived with the husband’s parents (certainly that’s where the marriage took place) and, if he had any, his brothers’ families – so we might imagine that this task was shared between many women.

Political Exclusion

Spartan women were precluded from taking part in the political system, as everyone who wasn’t homoioi was, unless we choose to give some credence to Aristotle’s suggestion that they had undue influence over their men.

However, Aristotle’s basis for this belief is problematic. He says:

‘It is true, therefore, that at the outset the freedom allowed to women at Sparta seems to have come about with good reason, for the Spartans used to be away in exile abroad for long periods on account of their military expeditions, both when fighting the war against the Argives and again during the war against the Arcadians and Messenians …’

[Pol 1269 again]

[Dates of these engagements in order: Argives: ~546BCE; Arkadians: primarily against the Tegeans, which included the infamous Battle of the Fetters ~550 BCE; Messenians: presumably he means the Third Messenian War, ~464 BCE, though he may be referring to the much earlier Second, which was in the 7th century BCE.]

This idea is spurious – let me explain as briefly as I can.

Spartiates, according to the Laws, were required to live in Sparta at all times when they weren’t on active service elsewhere. The gerousia, the board of 28 elders (who weren’t the kings) were all beyond the age of military service so they would always be in Sparta. The gerousia was instituted very early on and was almost certainly in place during the 6th century.

Only one king was permitted to march with the army at any given time, so there was, in theory always one king in Sparta (except during the times there was only one king at all, of course). This was current from the end of the 6th C BCE (~506 BCE.)

Men who had more than three male children were exempt from military service and would’ve remained in the city at all times, too – though this is often argued to have come into currency only after the Great Earthquake of ~464 BCE.

Those who marched out with the army would only have been a portion of the military-aged men. The army was selected by bouai (age groups), and only some of those groups were called into service for any given campaign. It was never the case that all the men of military age were sent from Sparta at once.

Though Aristotle is talking about the 6th century BCE, common sense tells us that some of these elements must still apply. There’s no version of reality in which all the men old enough to do so march out to war, leaving a city with only the women to take care of things. It simply never happened.

What’s more, there’s an issue with this claim of them being absent for an extended period of time – and it crops up in a lot of talking points, not just around women. During the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides tells us the longest duration of the army’s absence from Sparta was 40 days, and this occurred in two campaigns.

There’s a good reason why campaigns couldn’t be much longer than this, and that’s the difficulty in the provisioning of food. Twenty days appears to be the outer limit of what could be brought from Sparta. If this was an issue in the 5th century, there’s no reason to suppose it was easier a hundred years earlier or more.

Anyway – This is the long way of saying that Aristotle is wrong. Women were extremely unlikely to have been left to their own devices for long lengths of time.

Marriage and Children

Women were betrothed in exchange for a dowry, and her husband was chosen by her father or male guardian.

To quote Aristotle again:

‘… He [ie. a woman’s (explicitly) male guardian] is allowed to give an heiress in marriage to whomever he likes; and if he dies without having made directions as to this by will, whoever he leaves as his executor bestows her upon whom he chooses.’

[Aristotle again, from the Politics.]

Even once a woman was married, she wasn’t protected from being given to other men without her consent – and the emphasis is always very obviously on the production of children.

‘[Lykourgos] observed, however, that where an old man happened to have a young wife, he tended to keep a very jealous watch on her. So, he planned to prevent this too, by arranging that for the production of children the elderly husband should introduce to his wife to any man whose physique and personality he admired.

Further, should a man not wish to be married, but still be eager to have remarkable children, Lycurgus also made it lawful for him to have children by any fertile and well-bred woman who came to his attention, subject to her husband's consent. And he would approve many such arrangements. For the women want to have two households, while the men want to acquire for their sons' brothers who would form part of the family and its influence, but would have no claim on the estate. For the production of children, then, he made these arrangements so different from those of others.’

[Xenophon OSS]

Referring back to my initial definition of liberation, I think this makes quite clear that women didn’t choose ‘whether to marry or not and who,’ and it’s equally clear they didn’t have anything approaching full bodily autonomy.

Freedom?

In summary, I don’t believe that Spartan women were liberated in any sense that we would recognise as such today. Their privileges, assuming they weren’t all invented by Athenians, were small, and soon gone.

If we wanted to follow the path to a utopian ideal for them, we would have to take these sources at more-or-less face value, while ignoring a couple of really important points.

The ‘liberated and empowered Spartan woman’ as she appears in the ancient sources is a construct of (mainly) Athenian men with a vested interest in reinforcing their own marital norms, social behaviour and patriarchal authority - directly in contrast to Sparta.

The Spartan women in these texts are deliberately designed to be Other – to be despised and derided, as the Other always is.*

Also, to come out of this exercise with anything like a liberated Spartan woman before us, we must engage in serious cherry-picking, ignoring those sources, particularly around eugenics, plural marriages and ‘wife-loaning’, which make it absolutely clear that women were in no way in control of their lives or their bodily autonomy within marriage.

~~~~~~~~

[*For those who aren’t familiar with the terminology related to post-colonialism, Othering is a key tenet of the theory of Orientalism. I studied post-colonialism pretty extensively as part of my English degree – it is very applicable here in Australia, but the theory is useful in studying history at least as much as literature.

Orientalism, amongst other things, posits that the centre of power (sometimes referred to as Mother, or the Centre - in this instance Athens), knowingly, deliberately creates a distance between itself and the periphery (the Other or the Periphery, in this case, Sparta) by developing an image of them as lesser, not-like-us, and essentially bad and wrong. There is very often no necessity for this to be true – it must have just enough truth in it to be believed by the audience.

In modern times in the west, we can see this play out in rhetoric around Muslims, the Middle-East, and closer to home for me, the Aboriginal peoples here in Australia.

You can find more about this theory in the work of Edward Said, particularly his book of the same name, Orientalism. It’s not an easy read (theory never is), but definitely worthwhile as an approach to understanding how the centre of power denigrates those on the periphery.]

#I'm posting this before the planned section on the hypomeiones#because I have to stop tinkering with it#I have spent far too much time on this#ancient women#sparta#spartan women#ancient sparta#ancient history#ancient greece#lakedaimon#orientalism

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Those who rush across the sea change their sky, not their soul.”

—Horace

#my art#digital painting#digital art#procreate#latin#ancient women#ancient history#ancient rome#horace#latin quotes#latin scholars#Roman inspired art#art#painting

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

How different were the lives of Athenian and Spartan Women? part two - motherhood & education & society

In part one of this series, I discussed the differences between Spartan and Athenian women when it came to the marriage customs of their polis. I will now continue the discussion of their differences in their roles in society - more specifically, motherhood & education.

Motherhood & Education

The value of women in these two societies can be highlighted by how the individual polis educated and prepared its female citizens for motherhood.

The methods Athens used to prepare its female population differ significantly from the process Spartan women passed through. Athens' stance on the involvement of women in the production of children is explained in this extract from Aeschylus' Eumenides:

'I shall explain this- and speak quite bluntly, so note.

She who is called the mother is not her offspring's

Parent, but nurse to the newly sown embryo.

The male - who mounts- begets. The female is a stranger.

Guards a stranger's child if no god bring it harm.

I shall present you evidence that proves my point. There may be a father, and no mother.'

In this description of impregnation, the woman is but a vessel to house an embryo. The Athenian perception is that the role of the mother is passive. She is but a host for all the efforts of men.

Pomeroy explains that women are but a 'fertile field' when it comes to childbearing: a tool for men to create male heirs. (Pomeroy. 1975: 65) This is then reflected in the treatment of women in society. There is no need for physical education or literacy for a girl - in the years that boys pass through schooling, young girls are already married and having children. Women are also barred from many workplaces involving reading and writing, such as political offices.

Due to this, any education a girl is likely to receive in Athens would be domestic, with instruction from their mothers in the practice of weaving and housekeeping.

This is very unlike the girls who were raised in Sparta. While there is no significant amount of evidence recording the learning of reading or writing by Spartan girls - Herodotus recounts the tale of Gorgo, the daughter of Kleomenes I and wife of Leonidas. (Her. Histories. 7.239.4; Milender. 2017: 503) In Herodotus' work, the Spartan princess is responsible for decoding a secret message concerning Xerxes' plan to invade Hellas (Greece). This extract shows Gorgo's ability to comprehend wooden writing tables, and problem-solving at a level equal to the men in this scene, implying a degree of literacy - for at least - noble Spartan women.

The Spartan approach to motherhood stands apart from the Athenian ideas; the woman is more than just a house for the embryo. In Sparta, it is understood that a woman's well-being affects her child's well-being. When looking at Spartan law regarding women, the aim was singular - developing maidens into mothers. (Carroll. 2004. 133)

As explained by Xenophon, the Lycurgan laws demanded a similar level of physical fitness between men and women to produce 'vigorous offspring'. (Xen. Lac. 1.4; Milender. 2017: 506) For women to have time to adhere to this firm regimen, the tasks of maintaining the household would fall to enslaved people (this is not to say Athens didn't also enslave people, their women just worked more in the home). The lady of the house might still have a delegating role, but slave women would complete the many menial tasks. (Xen. Lac. 1.4)

In this instance, Sparta demonstrates care for their female citizens that Athens does not possess; as Plutarch recounts, Spartans believed that their women were the only women who mothered real men. (Plutarch. Sayings of the Spartan Women. 240.5) Because of this view, Spartan mothers were given the circumstances where they might be best able to focus on their most important role: childbearing.

Society

The attitudes perpetuated by Athens' and Sparta's view on motherhood trickled down into other aspects of these women's lives.

In Athens, the household's responsibilities kept a woman confined to her home, fulfilling the demands of her husband, infant, and home. For the wealthier woman, there would be no need to leave her home daily as she would have a collection of enslaved people to send errands on. (Pomeroy. 1975: 80)

An Athenian with little money and therefore fewer enslaved people would find a company with other women in completing small chores outside the home: fetching water, washing clothes, and borrowing utensils. (Pomeroy. 1975: 80)

Other than festivals and funerals, Athens' separation of the sexes was very apparent. The genders were kept separate in public and within the home through private architecture. Men and women inhabited different house sectors, usually with the wife and female slaves occupying the same space. (Pomeroy. 1975: 80) Pomeroy explains the best qualities admired in Athenian girls and women are 'silent, submissive, and abstinent for men's pleasures. (Pomeroy. 1975: 74) The only way an Athenian could fulfil this standard for women would be to keep herself out of public spaces and stay in the household, completing tasks set for them by their husbands or keeping in the company of other women.

However, even the gathering of women was discouraged by Athenian husbands as it was thought gossiping would lead to marital discontent. (Carroll. 2004: 171) So, Athenian women were left with little other than to attend to their children and keep the household in order.

On the other hand, as I have previously mentioned, Spartan women were deterred from extensive housework as they had a much more critical role in maintaining physical fitness and raising children. Unlike segregated Athens, some sources describe the interaction of Spartan men and women in the gymnasium.

'They leave their houses in the company of young men, thighs showing bare through their revealing garments, and in a manner, I cannot endure, they share the same running tracks and wrestling places'. (Eur. Andr. 595-601)

In this extract from Euripides' Andromache, Peleus - King of Pythia - expresses great dislike for Spartan girls being permitted to share the same running tracks and wrestling places as Spartan boys.

The only aspects of training girls and women were kept from were those which would be more beneficial to a soldier, sword fighting or spear throwing.

Another way Spartan women were able to participate in society was through economics. Land ownership in both Athens and Sparta was a privilege of being male. Inheritance passed through the male line, so land and wealth would go from father to son.

However, Sparta provides many examples of wealthy heiresses that either were provided large dowries or were patrouchos (a fatherless and brotherless woman who, by default, gets to inherit her father's property).

In Euripides' Andromache, we are given the characterisation of Hermione (daughter of Helen and Menelaus); through her we get a glimpse of a Spartan woman who has maintained control over the property she was given as a marriage settlement from her father. (Eur. Andr. 147-53, 873-2; Milender. 2017: 511) Hermione uses her inherited wealth to 'speak her mind'.

Later in Spartan history, the ownership of land by women became more commonplace as the male population declined due to military losses. (Martin. 1947: 6.13) Because of this, women with land grew in power and influence, especially in the marriage market.

When a man died, his land was not divided between his sons; it would be inherited by the eldest. So, younger brothers would seek out women with property to avoid poverty - giving landowning women great leverage when finding a husband.

Bibliography

Aeschylus. Eumenides, trans. J. Peller Hallett. [Perseus Digital Library]

Euripides. Andromache, David Kovacs, Ed. [Perseus Digital Library]

Euripides. Iphigenia in Aulis, trans. F. Melian Stawell, [G. Bell] (London, 1929)

Herodotus. The Histories, trans. Aubrey De Sélincourt, [The Penguin Group] (London, 1954)

Plutarch. Lacaenarum Apophthegmata. [Loeb Classical Library edition] (1931)

Xenophon. Constitution of the Lacedaimonians, E. C. Marchant, G. W. Bowersock, tr. Constitution of the Athenians., Ed. Perseus Digital Library.

Carroll, M. Greek Women, [University Press of the Pacifiic] (Honolulu, 2004)

Martin, T.R. An Overview of Classical Greek History from Mycenae to Alexander. [Perseus Digital Library] (1947)

Millender, E.G. ‘Spartan Woman’, in Powell, Anton. Ed. A Companion to Sparta, [John Wiley & Sons, Inc] (New Jersey, 2018)

Pomeroy, S.B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives & Slaves, [Schocken Books Inc] (USA, 1975)

Wells, O. 2021. Love, Sex, & Marriage in Ancient Greece, World History Encyclopaedia. worldhistory.org/article/1713/love-sex—marriage-in-ancient-greece/, 20 November 2021

#classics#classical civilisation#ancient greece#ancient greek#greek#athenians#spartans#sparta#athens#women#athenian women#spartan women#ancient women#uni student

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Classics#women in antiquity#women in Greek epic#ancient Greek women#motherhood in ancient Greece#ancient women

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love you people going into "useless" fields I love you classics majors I love you cultural studies majors I love you comparative literature majors I love you film studies majors I love you near eastern religions majors I love you Greek, Latin, and Hebrew majors I love you ethnic studies I love you people going into any and all small field that isn't considered lucrative in our rotting capitalist society please never stop keeping the sacred flame of knowledge for the sake of knowledge and understanding humanity and not merely for the sake of money alive

#classics#mythology#ancient greek mythology#ancient roman mythology#comparative literature#latin#hebrew#ethnic studies#fuck capitalism#communism#i love my useless degree idc#academia#university#dark academia#Greek#philosophy#liberal arts#humanities#women and gender studies#cultural anthropology

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't want this to be a surprise. I just want it to be accepted fact that women's roles in the ancient world were vastly different from the ones later one, and that we have imposed our societal expectations on peoples about whom we know next to nothing.

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fresco showing a pretty young woman, wearing a veil (I think).

She’s stooping to pick a flower with her right hand. With the eye of faith, you can see that she's cradling a bunch of flowers in the crook of her left arm.

Vila Ariana, Castelammare di Stabia.

#fresco#ancient art#ancient women#vila arianna#Castellammare di Stabia#ancientprettythings#original photography#women#onetinydetail

27 notes

·

View notes