#Warner Bros exploited him and countless others

Text

“That bland smile of his is ten times as nasty as the frowns from lesser villains . . .”

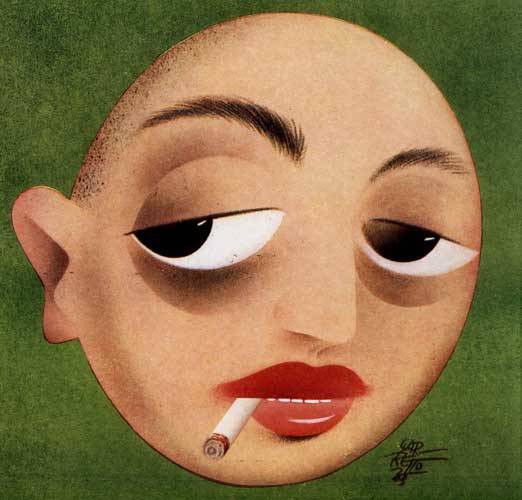

Italian artist Paolo Garretto drew the above caricature of Peter Lorre to announce his upcoming role in Secret Agent (1936). Source

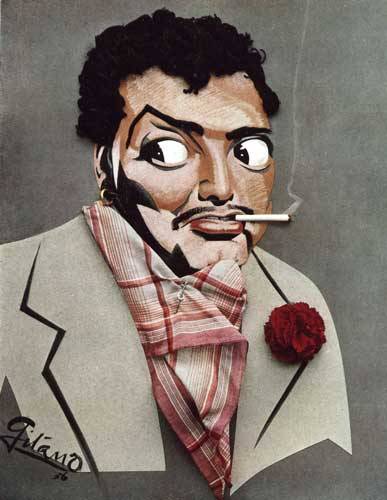

While Secret Agent was in release in London, the artist Gitano created a portrait of Peter as "The General." Besides paint, he used skeins of black silk, a scarf, a gold earring, a boutonniere, and a tie-pin. Mmm, a tactile Lorre! Source

Speaking of imagery and such, Peter was allegedly gratified by impersonations, whether vocal or artistic. However, he had signed away his screen image as early as 1941:

"Warner Bros. held a patent on Lorre’s physical likeness, caricaturing the actor in animated cartoons that depicted a baby-faced villain with bulging eyes and nasal whine."

May 24, 1941, Warner Bros. released “Hollywood Steps Out,” which featured a gallery of stars. Eying a naked woman clothed only by a bubble, Peter Lorre says, “I haven’t seen such a beautiful bubble since I was a child.”

April 11, 1942: In Dr. Seuss’s “Horton Hatches the Egg,” a Peter Lorre Fish "spots the elephant atop a bird’s nest, pulls out a pistol, and shoots itself in the head, a scene later deleted by several television networks for its violent content."

Other animated appearances include:

“Hair Raising Hare” (June 8, 1946) with Bugs Bunny

“The Birth of a Notion” (April 12, 1947) with Daffy Duck

“Racketeer Rabbit”(September 14, 1946) with Bugs Bunny

Lorre's screen image also appeared in a 13-week episode of a Batman & Robin newspaper strip, entitled "The Two-Bit Dictator of Twin Mills," (October 30, 1944 - January 26, 1945).

Source

It's bugged me since I've known about it that Peter didn't even get any $$ for these images while he was alive - money he sorely could have used. But Warner Bros sure did.

#peter lorre#peter lorre cartoons#peter lorre caricature#Warner Bros exploited him and countless others#retroactive arrgh

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s the Anniversary of Everything!

By any measure, the summer of ’69 was, as the kids say today, “a lot.”

June had the Stonewall riots, a landmark moment in the modern gay rights movement. July, the moon landing. August, the grisly Manson murders, followed by the endless mud of Woodstock.

These events have been fodder for countless songs, movies, university courses, history books and romance novels. And now, in 2019, they have begot another special summer: of 50th-anniversary celebrations that are public, elaborate and full of nostalgia. Millions of people from around the world are joining in, along with sneaker designers, toothbrush companies, hotels, museums and news organizations.

Far be it for us to deflate the spirits of those, say, dancing in constellation-printed rompers and drinking Budweiser at the Space Center Houston a couple of weeks ago. But then to happen upon less momentous commemorations, like a copy of People magazine celebrating the 30th anniversary of the movie “When Harry Met Sally” at the corner newsstand, is to wonder: Just what is the point of marking them? Is doing so essential somehow for society’s psychological well-being, an attempt to collectivize experience increasingly diffused by the distractions of the internet? Or just more chances for corporations to sell us stuff?

Also, what’s with the nice round numbers (or, more specifically, multiples of five)? “We need to point out the strangeness of it, the peculiarness of it, the fact that no one voices dissent in any media forum, to say ‘We are overdoing this’ or ‘Let’s talk about something else this weekend,’” said William Johnston, a history professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and the author of the 1991 book “Celebrations: The Cult of Anniversaries in Europe and the United States Today.” “Something gets wiped out because it’s not an even number. Hitler’s assassination attempt, it was 51 years ago, so we won’t pay attention to it.”

Many people seem to enjoy celebrating significant anniversaries of cultural occasions almost as much as those of their own marriages.

Nineteen percent more people visited Space Center Houston in the first week of July than the same week last year, according to the organization.

Five million people (more than half of the New York City’s entire population) attended the Stonewall 50 celebrations that culminated the last week in June; 200,000 of them, about 130,000 more than last year, walked in the official parade, wearing rainbow outfits and Lady Liberty costumes, according to Chris Frederick, the executive director of NYC Pride.

“Invitations for Pride events were coming from every brand, every hotel, every bar, every toothpaste,” said Ross Matsubara, 34, a publicist and style director in New York who is gay. “I think if I was an older cis male who isn’t as prideful, I might be sick of it.”

Turn it On Again

One of the main reasons this hype is happening now, said Carolyn Kitch, a professor of media and communications at Temple University, is because these Big Three events were among the first to have vibrant, cohesive footage (and much of it in color). “There are iconic photographs, iconic news coverage that every television station and newspaper wants to use,” she said. “It makes the stories take on a greater importance.”

Mr. Johnston pointed out that “100-year anniversaries only have black and white photos. That’s why 1969 is just ideal. All the television stations have tapes of Woodstock, Stonewall, the moon landing. You can ignore it for the weekend of the anniversary if you want, but it’s the same choice as choosing to turn off the World Series.”

People also live longer now, and are in better health in their 70s and 80s. That means there are a lot of people who were adults during the original event and want to revisit the moment 50 years later (perhaps more clearheadedly).

In 1969, Steven Janney Smith was a 19-year-old with long, unruly hair and a wardrobe that included a rhinestone-collared T-shirt. He remembers driving all night from a party in Detroit at 100 miles an hour to get to Woodstock for the tail end of the festival. “I was at a house party, and I just decided, ‘I want to go,’” said Mr. Smith, now 69 and an interventional radiologist in Chicago. “I can’t remember what bands we saw, but I remember it stunk. The festival was in a cow pasture, which nobody ever mentions in rhapsodic stories about that sacred gathering.”

Still, the anniversary is giving him a chance to pull out his photos and figure out how to get some of that freedom back. “There were no cellphones then, no one knew where you were. I didn’t have any place to be, I didn’t have any worries in the world,” Mr. Smith said. “That was a type of freedom that I need to get back now.” He paused: “I need to find somewhere to celebrate this anniversary with people who get it.”

One group he might not want to party with are the younger generations, for whom the monoculture is a distant concept, flocking to these celebrations.

For some it’s a fascination for events that happened before their time. “I’ve always joked my biggest regret in life was not being born in time for the moon landing,” said Stefanie Waldek, 27, a writer, editor and digital producer based in Brooklyn who traveled to Houston for the lunar landing anniversary. “I think that the moon landing was the greatest achievement of mankind, and I wanted to be surrounded by people who made it possible.”

Ms. Waldek met astronauts from the Space Shuttle program and listened to flight controllers who were part of the missions speak. She also met current administrators who are plotting upcoming missions back to the moon and then to Mars. She visited the newly restored mission control center made famous by the movie “Apollo 13.” Still, “I don’t necessarily think that being in Houston for the 50th anniversary could ever compare to watching the landing live in 1969,” she wrote in an email. ”But I did feel a great sense of gravitas.”

For others “milestoning,” as we’ll call it, might offer a chance to escape their current troubling reality of ecological emergency and mass shootings. “The frenzy of collective remembering supplies an excuse briefly to forget everything else,” said Mr. Johnston.

Emilie Aries, 31, who owns a professional development company based in Denver, will spend the Woodstock anniversary weekend at her in-laws’ farm in North Branch, N.Y. Her father-in-law was at the original event, and he’s inviting his peers over for a party with a local band. Guests have been instructed to bring photos of themselves from the ’60s to display on a tree.

“I want to be around all these hippies and talk to them about how they rebelled against the establishment,” Ms. Aries said. “It is a counter to the hate we are seeing from the current administration today. I want to be reminded of the power of love and see if I can take away any lessons.”

Mr. Smith is excited that some millennials want to learn from his generation. “I always thought they see baby boomers as some sort of fossils who screwed up things for them like climate change,” he said.

The Rainbow Reconnection

The main argument against anniversary celebrations, particularly the glitzy 50ths, is that they’ve been corrupted by corporate interests.

Corporate sponsors of Stonewall 50 included T-Mobile, Mastercard, Hyatt, Macy’s, Target, Delta, Diet Coke, Unilever, Nordstrom, MAC, Skyy vodka, Omnicom Group and many, many others. In late July, a month after the anniversary celebration, there was still a sign on a bus stop in the West Village from TD Bank announcing itself as “A Proud Partner of Stonewall 50.”

“Commercial enterprises are exploiting this event to call attention to their product,” Mr. Johnston said. “I think most people can see right through that.”

But while Mr. Matsubara noted rainbows at a WeWork, an “old fuddy-duddy dress shop” and on Seamless, he was untroubled. “Some might be doing it for the wrong reasons, but I also feel these brands and organizations have the right to celebrate in their own way,” he said. “Everyone else is.”

Including, perhaps most tellingly, media organizations.

Warner Bros Television is honoring the 25th anniversary of “Friends” (didn’t we just honor the 20th?) by staging a month long pop-up of Central Perk, its fictional cafe, in SoHo. Starting Sept. 7, there will be set recreations, photo ops and, of course, a chance to buy merchandise from the on-site store.

Paramount Pictures and Fathom Events have announced they will be screening the original 1979 movie “Star Trek” in theaters for two days in September to commemorate the movie’s 40th anniversary (this following Columbia’s successful revival of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” in 2017).

As it goes monthly this month, Entertainment Weekly magazine, always a chronicler of significant cultural anniversaries, will probably be doing so even more. Besides allowing media to relish its own past successes, anniversaries give television stations, film production companies and, yes, journalists a break from having to create new content all the time.

“It’s very convenient,” said Mr. Johnston. “You can decide what you want to cover five years, 10 years, 50 years ahead. Everyone can decide what we will be celebrating in 2029.”

Sahred From Source link Fashion and Style

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2OB7oEx

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

by Paul Batters

Recently, Harrison Ford made an interesting declaration regarding one of his most iconic characters, which is also part of one cinema’s most financially successful franchises – Indiana Jones. Famously close-mouthed about previous roles, the actor made the comment in anticipation of the Disney announcement that a 5th instalment of the Indiana Jones franchise would be released in July 2021. Basically, Ford claimed the role as permanently his, stating:

‘Nobody else is gonna be Indiana Jones! Don’t you get it? I’m Indiana Jones. When I’m gone, he’s gone…’

Whether this declaration is tongue-in-cheek or serious, I cannot ascertain nor does it particularly matter for the purpose of this article. The vast majority of fans would probably agree with Ford, as Indiana Jones is one of cinema’s most loved action heroes. (If his friend George Lucas is anything to go by, there is little to be held sacred in remaking or re-hashing films. Star Wars, anyone?)

But it does raise an interesting question – are there screen characters which should never be re-visited?

It’s also a polarising question and one which probably raises another more divisive question – should classic films be re-made? Cinema is certainly in a strange place at the moment, and there have been consistent attacks on the state of film-making with criticism aimed at the lack of creativity, the focus on special effects and CGI and particularly the obsession on re-makes. The Marvel and DC domination has been discussed ad nauseam and the recent Godzilla movie speaks to this issue as well. (What’s the current tally of Godzilla movies since the 1954 original?)

The criticisms are not unfounded, and this reviewer certainly agrees with the aforementioned sentiments regarding cinema’s current sins. However, are these problems simply a contemporary phenomenon? Or has Hollywood been re-making films and re-casting iconic roles since its’ earliest days?

Indeed, the ‘re-make’ has been a part of entertainment that goes back to ancient times. Initially, the ancient Greeks, who created the concept of drama, would see performances only the once and their plays were unique, one-off experiences. However, over time, those plays were performed again and again, particularly during the Hellenistic period. It was also meant that those plays stayed alive and they are still with us today. Consider the plays of Shakespeare. They have been performed, interpreted and even changed (depending on context) since Elizabethan times. King Lear has been interpreted through a whole range of approaches from a medieval Japan context to one set with 1950s Eastern Bloc /Cold War aesthetics! The richness of these stories in language, theme, character and emotion are still alive because they have been performed for hundreds of years. And of course, the Bard’s stories have been interpreted for the screen. Think Olivier’s 1945 film version of Henry V, which is often considered one of the finest screen interpretations of the play. Does this become the one and only version, never to be remade? What of Baz Lurhman’s Romeo And Juliet (1995)? It is not the first nor will it be the last telling of the tragic story of two star-crossed lovers.

The truth is that some of our most loved, revered and celebrated films are remakes, whether we realise it or not. We often chide Hollywood for remaking films within only a few years of each other but actually it’s been a practice since the silent days. By the time, Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde was made in 1932 at Paramount, the story had been filmed at least 8 times, with three versions being made in one year! (1920 to be precise, two in the U.S and one in Germany). John Barrymore’s 1920 turn as the infamous dual personality was a benchmark performance but March as the doomed doctor is perhaps the most superb in sound film history, with even the great Spencer Tracy unable to reach audiences in the 1941 version with Ingrid Bergman.

The same is true for quite a number of films based on classic literature such as A Tale Of Two Cities, Treasure Island, The Three Musketeers and A Christmas Carol – all being filmed numerous times. By the 1935 MGM version, David Copperfield had been made 3 times. The story of Oliver Twist was on its’ 8thversion in the loved 1968 musical Oliver!(with the film being made 6 times during the silent era!). William Wyler’s Ben Hur is often cited as the greatest epic ever made and a standard by which other ‘big films’ are measured. Yet it too is a remake of the 1925 silent epic starring Roman Navarro and Francis X. Bushman. (Ironically, the recent remake of Ben Hur was critically panned and financially an unmitigated disaster).

youtube

youtube

Interestingly enough, Cecil B. deMille is an example of a director who revisited earlier films he had made and gave them a new perspective. The Squaw Man (1914) would be remade two more times in 1918 and 1931! Of all the films he made, his most celebrated, known and loved is his final film, The Ten Commandments (1956), a far superior remake of his own 1923 silent version. In this case, the original is not the best. The 1956 version is the quintessential epic tale, resplendent in Technicolor, with all the kitsch, pageantry and excitement of Biblical proportions that are synonymous with deMille and the epic film.

youtube

youtube

But not only have epics and tales from classic literature been remade to great or greater success. Contemporary stories have been revisited as well. In the world of film noir, one film which justifiably makes every top five list was on its third remake when it was redone by John Huston. The Maltese Falcon (1941) remains one of the greatest films ever made, far out-pacing it’s prior two incarnations which would have become little more than a footnote in cinema history. The previous 1931 same-titled version starring Ricardo Cortez and Bebe Daniels is a little stilted, whilst its’ 1936 remake, Satan Met A Lady, starring William Warren and Bette Davis feels more like a typical Warner Bros. programmer and was even considered by critics at the time, such as Bosley Crowther, as ‘inferior to the original’. Neither are remarkable and again, the original is not the best. Huston’s version of the Dashiell Hammett pulp fiction novel, would help to create the tropes and cinematic expression for film noir, and Bogart’s performance as private eye, Sam Spade has become legendary and would make him a star.

Unfortunately, there is sometimes an element of exploitation that comes with the remake. But Hollywood is a business and driven by profit. If an audience responds, then it the film is deemed a success. The horror genre is one where the remake is a constant, driven by the profit margin rather than artistic merit. That has certainly been the impression felt with Universal’s recent attempt at ‘re-booting’ the classic Universal monsters with disastrous results. (This writer feels that Universal was making an attempt to trash its’ legacy!) The classic monsters were first seen in monochrome but would be remade in the 1950s and 1960s in Britain by Hammer Studios, complete with full-blown colour, gore and sex. Exploitive? Perhaps. Yet audiences saw a new interpretation of the undead Transylvanian count – from a dream-like, hypnotic and slow-speaking Lugosi to an animalistic and vivid Christopher Lee, complete with bloodied fangs. Horror fans often find it difficult to choose, with the character of Dracula ‘belonging’ to both actors. Yet Lee would be less successful with the Frankenstein monster, as would many who preceded and followed Lee, and the monster has been firmly associated with the brilliant performance of Boris Karloff in the original 1932 film and its’ two sequels. Still, the Hammer remakes resonated with audiences, offering something new and exciting.

Yet there are characters that belong to certain actors and actresses and their ownership of those performances are complete. It is impossible to think of anyone else but Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara or for that matter, Clark Gable as Rhett Butler. And of course, Gone With The Wind is a film that no-one would dare remake. The same could be said for Casablanca,again a film with iconic performances from Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, a song that had stood the test of time in its’ poignant definition of love and of course some of cinema’s most famous lines. How could it be remade? The story of Robin Hood has been told numerous times, with mixed results and mixed reviews. Arguably, the role was firmly identified with Douglas Fairbanks Snr, one of the great silent stars, after his 1922 film was a huge hit; until Warner Bros. remade the film in full colour in 1938, with Errol Flynn. A natural for the role, Flynn has owned the role since, despite numerous A-listers taking on the role over the decades.

There are countless other roles and films which, if recast or remade, would results in loud cries of protest. And perhaps rightfully so. Could The Wizard Of Oz be remade? (Actually, it, too is a remake!) How about Edward G. Robinson as ‘Little’ Caesar Bandello? Imagine a ‘reboot’ of Chaplin’s work. Or Hitchcock’s films. (It’s been done!) Singin’ In The Rain? Double Indemnity? The Godfather? Metropolis? Duck Soup? Some Like It Hot?

In the end, a remake will work or fail if it resonates with the audience. For better or for worse, that’s the lowest common denominator that determines a film’s eventual worth andif it will stand the test of time. For silent films (and indeed even some sound films from the golden years of Hollywood), this has proved difficult. Aside from cinephiles and classic film lovers, silent films find difficulty in gaining traction in a mainstream market and for audiences not exposed to silent film. Additionally, we have audiences trained to expect blockbuster films over-cooked with CGI and action every 30 seconds. A silent film, without sound, colour and very different contexts finds it difficult to gain a foothold.

But all the technological advancements in the world cannot replicate, re-design or replace the impact of story.

It takes a fair amount of courage and risk when a remake is given the green light. It means big shoes to fill and an attempt to draw out a performance from under the giant shadow of its’ predecessor. Cinematic history shows that it does happen. But there are films that are like classic works of art. Can a work by Monet or Dali be redone? Should a piece of music by Mozart or Brahms be re-written? And the importance of textual integrity cannot be over-stated either. The recent tragedy of the near destruction of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, will see deep discussion and debate on how to ‘remake’ what has been lost or damaged. Will it be in keeping with the historic and architectural integrity of the building? Will it be true to the cathedral’s past whilst reflecting the modern era (or does it have to)? And how will people react in the present and in the future to any change or lack of change?

The remaking of classic film shares a similar dilemma.

There are advantages to classic films being remade. It sounds almost unthinkable but Nosferatu (1922) would be successfully remade by Werner Herzog (in an English AND German version!) in 1979 with the famed Klaus Kinski in the title role, to great critical and commercial success. It is an impressive film, with stunning visuals, incredibly deep pathos and emotion, and Kinski is outstanding as the vampire. As a result, it also brought new interest in the original 1922 film. If remakes can arouse interest, educate audiences and broaden the experience of cinema, whilst offering a new and exciting perspective/interpretation, then it serves a great purpose.

But just because classic films can be remade, does not mean that they shouldbe. As already mentioned, Universal came close to trashing their own legacy with the attempted (and hopefully permanently aborted) reboot of the classic horror monsters, which felt watching someone take fluorescent spray cans to the Sistine Chapel. But as audiences, we do need to set aside prejudged notions and allow for new interpretations of stories. This is what provides a richness to cinema and art. Multiple and contemporary readings offer greater insights and new interpretations offer inclusivity to modern and future audiences – and there is great value in that prospect.

But new is not enough. ‘New’ for the sake of ‘new’ does not do justice to a work of art. Nor does new mean better. What is also important to recognise is that masterpieces do not and cannot be replicated. Nor do they need to be. We can already enjoy what exists, revisit them time and time again and walk away re-spirited, revitalised and emotionally moved.

Paul Batters teaches secondary school History in the Illawarra region and also lectures at the University Of Wollongong. In a previous life, he was involved in community radio and independent publications. Looking to a career in writing, Paul also has a passion for film history.

To remake or not to remake? The question on rebooting classic film. by Paul Batters Recently, Harrison Ford made an interesting declaration regarding one of his most iconic characters, which is also part of one cinema’s most financially successful franchises – Indiana Jones.

#ben hur#cinema#classic film#classic horror#dr Jekyll and mr hyde#dracula#epic film#Hollywood#nosferatu#remake#silent era#the maltese falcon#the ten commandments

0 notes