#The Little Devil: In Defense of Salaì

Text

1. The Accused

In the Louvre, there’s a red-pencil portrait of a young boy with unruly hair. Everything about this child crackles with electricity. The gaze of his large, heavy-lidded eyes radiates resentment. His lips are obstinately pressed tight, as if defying his captor to make him speak.

And yet he sits still and lets himself be drawn.

He’s not the one. We know he’s not, even if we’re not sure of his name. He’s been misidentified a million times, maybe due to our own wishful thinking. We say to ourselves: But he could be Salaì, couldn’t he?

Look at that face.

Sure he could.

Let's read the charges against him:

He’s a gutter rat, an urchin, an orphan.

He’s a thief, a liar, stubborn, greedy.

Even so young, he lures and seduces.

He’s a mercenary, hands stretched out to grab what he can.

He's a lousy painter, an imitator, a fraud.

He's a diva; petty, jealous, vain. He has two dozen shoes and clothing encrusted with jewels.

He's a sore loser. He’s dead weight.

Deserving nothing, he steals everything.

He keeps the best for himself.

He betrays and abandons.

He dies a pointless death.

He had it coming.

This is everything they say about him. But let's begin again, at the beginning.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I did on my summer vacation: Slept; chilled with my spouse; went thrifting/antiquing without a mask on; learned how to play Seeker’s Notes for relaxation & brain health; shaved my head for gender identity health; tried my very best to work on my acid reflux & depression (both of which have been well & truly trouncing me over the last 2 months); came THIS CLOSE to deleting all my blogs, then forced myself to sleep on it; turned my #3 sideblog into a literal shrine to Måneskin drummer Ethan Torchio (insert heart eyes for this gentle genderfluid bodhisattva); researched & wrote a micro-dissertation called “The Little Devil: In Defense of Salaì”, then printed it as a ‘zine and presented it to my art-history-major friend for review; finished (!!!!!) To Himling ; learned how to thread (if not actually USE) my new handheld sewing machine; missed Mr. Turner something fierce, and missed all of you even fiercer. What’s shaking?

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

During the first spring of pandemic, I wrote the following as a response to the RAI series Leonardo, which portrayed Gian Giacomo Caprotti di Orena, AKA Salaì - artist, factotum, and life partner of Leonardo da Vinci - as a prostitute who wormed his way into the great artist's workshop, household and bed. What shocked me about this take was not its novelty (it had none), but the regularity with which it has been used against its subject in the centuries since his death. At the time, I wrote:

For RAI to turn him into an opportunistic sex worker to explain his presence in Leo’s life (and gloss over the age difference between them) is false and lousy writing, though not exactly a deviation from past practices. But surely, surely it cannot be better to portray Salaì as a rentboy met by chance than as what he was– an innocent (if undisciplined) child from a poor but respectable working class family, given to Leonardo for fosterage. Robbing Salaì of his virtue to preserve Leonardo’s is a shit move that creates a damaging narrative. Why does one have to be a whore so that the other can be the hero? Why can’t Leonardo and Salaì both be the heroes of their shared story?

Salaì was a real person who deserves a better legacy than this.

What follows is my attempt to provide it. Thank you for reading.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

2. The Stranger

On the Magdalen’s Day in 1490, ten-year-old Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno enters the household of Leonardo da Vinci as a famiglio, or servant. Craft apprenticeship being a form of indenture, the boy now belongs to the maestro, who will make a respectable artist of him if all goes well.

It will not.

Within forty-eight hours, Gian Giacomo steals four lire from the maestro's purse, lies shamelessly when confronted about it, and makes such a spectacle of himself at dinner that a stunned Leonardo feels driven to document it in his journal:

I went to sup with Giacomo Andrea (de Fererra, an architect friend)… and the said Giacomo (Salaì) supped for two and did mischief for four, for he brake three cruets and spilled the wine…

The ink is barely dry on this account before “the said Giacomo” adds new entries. First he nicks a fellow pupil’s silver stylus and hides it in his own locker. He then proceeds to empty a footman's purse, after which he filches a piece of costly Turkish leather, trading it for anise bonbons which he naturally gobbles down all by himself. Thus fortified, he lifts another stylus from a different apprentice and is caught in the act once more…

Ladro, bugiardo, ostinato, ghiotto: thief, liar, stubborn, glutton. These are the words Leonardo da Vinci uses to sum up Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno at age ten. His tone is exasperated, certainly-- but also amused, even sympathetic.

He, too, was once a stranger in a strange land.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

4. The Apprentice

As the junior-most pupil in the atelier, Salaì must do as Cellino Cellini advises in his treatise Il Libro dell'Arte:

…begin as a shop boy studying for one year, to get practice in drawing on the little panel; next, to serve in the shop under some master to learn how to work at all the branches which pertain to our profession; and to stay and begin the working up of colors; and to learn to boil the sizes, and grind the gessoes; and to get experience in gessoing anconas, and modeling and scraping them; gilding and stamping; for the space of a good six years. Then to get experience in painting, embellishing with mordants, making cloths of gold, getting practice in working on the wall, for six more years; drawing all the time, never leaving off, either on holidays or on workdays. And in this way your talent, through much practice, will develop into real ability.

That’s a lot of running around, which brings me to my next subject.

One oft-repeated factoid about Salaì is that he had twenty-four pairs of shoes. Twenty-four! Up rises the specter of a greedy, grasping Renaissance toyboy, draining his sugar daddy dry lira per lira to satisfy his footwear fetish…

The truth: Leonardo purchased the shoes at the start of Salaì’s apprenticeship. It’s right there, in the notebooks:

The first year—

A cloak, 2 lire,

6 shirts, 4 lire,

3 jerkins, 6 lire,

4 pairs of hose, 7 lire 8 soldi,

1 lined doublet, 5 lire,

24 pairs of shoes, 6 lire 5 soldi,

A cap, 1 lira,

Laces, 1 lira.

There are 20 soldi in a medieval lira. Each pair of Salaì’s shoes – humble canvas scarpets, most likely – cost a little over six soldi, a mere fraction of the cost of a cap or cloak. Their ten-year-old owner was growing fast. In light of that fact, two throwaway pairs a month might not be all that unreasonable.

That is we resent Salaì for. Cheap kid’s shoes, bought in bulk.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

6. The Other Half

Already the maestro’s student and muse, the Little Devil now becomes his partner. He and Leonardo share a room, a bed, their thoughts, their hearts. Leonardo deputizes Salaì to act as his emissary, delivering important messages and even money, which he (almost) trusts him not to pinch. He loans his young lover sums for this and that and even contributes generously to his sister’s dowry. And he buys Salaì clothes. Lots of clothes. A notable dandy himself, he encourages and underwrites his Devil’s flair for fashion:

I paid to Salaì 3 gold ducats which he said he wanted for a pair of rose-colored hose with their trimming…

I gave Salaì 21 braccia of linen to make shirts, at 10 soldi the braccio…

An inventory Leonardo makes of his wardrobe reveals that he and Salaì keep their clothes mingled together in the same trunk:

…One gown made of taffeta. One velvet lining that can be used as a gown. One Arab burnouse. One gown of dusty rose. One rose-colored Catalan gown. One cape of dark purple with wide collar and velvet hood. One coat of dark purple satin. One coat of crimson satin. One pair of dark purple stockings. One pair of dusty-rose stockings. One pink cap… A cape in the French mode, once owned by Cesare Borgia… a tunic of gray Flemish cloth, belonging to Salai…

They might even share, and that’s precisely why Leonardo itemizes the garments: he and his partner have begun to lose track of whose is whose.

What defines couplehood better than this?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

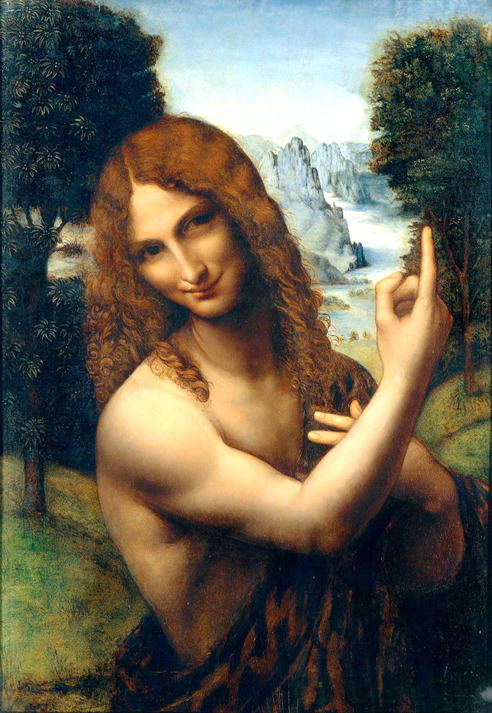

7. The Disciple

Critics maintain that Salaì was untalented, unremarkable, a mere imitator without style or subtlety. Over and over, his mediocrity is hammered home. If something about a collaborative work looks wrong, Salaì did it. If something looks right, it must be the work of another— sometimes Leonardo. One wonders why he kept Salaì around at all, when there were more worthy students to mentor.

But according to art historian Anna Maria Ferrari in Groves’ Dictionary of Art, Leonardo considered Salaì “an able pupil”. By twenty-five, Salaì “…had achieved some fame as a painter; Alvise Ciocha, an agent of Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua, described him as ‘very able for his years’ and invited him to advise Pietro Perugino who was working for her.” In Benezit’s Dictionary of Artists, Salaì is described as “one of Leonardo da Vinci’s most distinguished pupils”. And in Sotheby’s catalog for the 2007 auction of Salaì’s Head of the Christ the Redeemer, we find this:

Gian Giacomo Caprotti was one of Leonardo da Vinci’s most faithful pupils and the chief propagator of his art… Leonardo himself described him in his notebooks as a liar and a thief (but) admired him greatly for his artistic talent. Vasari considered Salaì to be Leonardo’s most faithful follower and he even went so far as to say that some of their works were (so similar as to be) confused… Unlike the other Leonardeschi - such as Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Marco d’Oggiono, Andrea Solario, Cesare da Sesto - Salaì did not embark upon an independent artistic career but seemed content in copying and interpreting his master’s works, thus disseminating Leonardo’s inventions throughout the first quarter of the 16th century. As Shell and Sironi have observed, ‘Salaì represents another kind of Leonardesco; the faithful replicator of Leonardo’s models and, by his own lights, executor of Leonardo’s intentions’…

When another painting by Salaì (Penitent Magdalen) came to auction in Paris in 2020, Anna Brady of the Art Newspaper wrote:

But da Vinci forgave him his petty crimes and Salaì stayed with him for more than 25 years until da Vinci’s death in 1519, serving as a financial manager, model, agent and lover and accompanying him on all his travels. He carried on painting, too, and became a teacher at the workshop in 1515. Leonardo left the Mona Lisa to Salaì upon his death.

The article goes on to describe how Italian art historian Cristina Geddo identified the Magdalen as Salaì’s:

In a video produced by the auction house, Geddo says she was able to make the discovery due to Salaì’s painting of Head of the Christ the Redeemer, recently donated to the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, which is signed ‘Salaì’ and dated 1511… Geddo adds the technique is ‘extremely faithful to that of the master… difficult to find in his other pupils, the Leonardeschi.’ She refers specifically to Salaì’s use of Leonardo’s characteristic sfumato but also to the many thin washes of diluted paint that are layered to subtle effect and create ‘a gradual passage from light to shadow which is incredibly close to Leonardo’s technique.’ Geddo also notes an ‘obsessive attention to detail’, particularly in the rendering of the hair.

Old Master specialist Eric Turquin adds:

Salaì was able to assimilate the fine technique of the master. He positioned himself as one of the most influential promoters of Leonardo’s models through the production of copies and variations of Leonardo’s masterpieces. But he is also the author of original works which bear witness to the master’s lesson interpreted with a certain autonomy.

Valuated at €348,000, Salaì’s Head of the Christ the Redeemer sold for over €506,000. Valuated at €150,000, Salaì’s Penitent Magdalen sold for close to €2,000,000.

What a loser, right?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

8. The Rival

By age twenty-six, Salaì has progressed both as an artist and as an administrator of Leonardo’s household. He has been empowered to manage the finances and assist the maestro with the younger pupils in the workshop. Though his contrarian side still surfaces – Non più guerre; mi arrendo, a weary Leonardo is overheard saying after a dispute – Salaì is settled, confident. He loves Leonardo, sees to his daily needs, offers him inspiration. He knows where he belongs.

True, if his schooling had followed the typical trajectory – fifteen-odd years from servant to pupil to journeyman to maestro – he’d have left already. But love and devotion give him a reason to stay, and in staying, Salaì comes into his own.

Enter Francesco Melzi.

A courtier’s son eleven years Salaì’s junior, Melzi joins the household in 1508 as a dilettante— a gifted young dabbler with no need to make a profession out of painting. He will serve as the maestro’s archivist, sorting and cataloguing mountains of notebooks for posterity.

What does Salaì make of this earnest, well-bred teenager? Does he dislike him at first sight? Does he perceive him as a threat? Or does he just shrug and toss the new kid a smock to protect his nice clothes?

Look at how intelligent Melzi is, comes the inevitable whisper. So cultured, so gracious, and beautiful besides. All this is a roundabout way of saying, Why does Leonardo want Salaì by his side when he can have Melzi?

He has them both. Every man’s got two sides, after all.

They’re a mismatched pair, Melzi and Salaì— one polished and intellectual, the other rough-edged and pragmatic. This doesn’t make one’s contribution superior to the other’s; nor does it ordain that they must naturally be at odds. If not friends, they are at least colleagues; Leonardo’s left and right hands. And they’re both artists—they’ve got that in common.

I like to think of them side by side, Melzi filling his sketchbook with playful caricatures while Salaì patiently blends his paint strokes with a single, careful fingertip. From time to time, Melzi leans in to study the older artist’s technique; during breaks, Salaì doubles over with laughter at young “Cecco’s” grotesqueries…

It’s a stretch, I know. But they work together for ten years— why not get along? Because harmony is boring and conflict moves things along. Because stories need a clear dynamic, an archetype to pin a plot on. Hero v. Villain. Winner v. Loser.

Melzi v. Salaì.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

9. A Journey, an Errand

In 1516, the newly-crowned King François I names Leonardo da Vinci his “First Royal Artist, Engineer, and Architect” and bids him come to France. That August, the artist decamps from Rome and journeys with his entourage north to Milan, west over the Alps to Geneva, then south to the Val de Loire.

All along the way, it is unclear whether Salaì is of the party. Maybe he leaves Rome first and travels ahead to Milan, or travels there with them but remains behind while they move on to Geneva. It could be he’s got personal business to attend; he is, after all, thirty-six years old, an adult with adult concerns.

Or perhaps it’s as the historians contend: there’s been a break-up, fueled by jealousy. Melzi has taken Salaì’s place in Leonardo’s affections. The Little Devil is locked out.

The travelers arrive at their destination in October 1516 and settle at the Manoir de Cloux (now Clos-Lucé), a royal residence near Amboise. The King awards them various sums according to their status. While Melzi is identified as a “gentleman” and receives 400 écus, Salaì (is he there or not?) is designated a “servant” and given only 100 écus, a pittance reported with glee by his present-day detractors.

But don't get too cocky just yet.

A year later, according to a detailed account written by his secretary Antonio de Beatis, Cardinal Luigi d’Aragona visits Cloux and enjoys a private viewing of three paintings identified as La Gioconda, Saint John the Baptist, and The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne. There is no mention of Salaì being present.

However, a Royal Receipt detailing the 1518 sale of the same three paintings to François I will be discovered in the Milan National Library archives in 2013. According to the receipt, this transaction is facilitated by Salaì himself, acting as Leonardo’s emissary.

A corroborative record has already been unearthed in the French National Archives; it reveals that in June 1518, François I instructs the Duchy of Milan to pay Salaì an exorbitant 2,604 livres “for certain panel paintings he has given to the King”.

The only clear indication of what is done with this money – or at least 125 écus of it – is a notarized agreement made by the exiled Massimiliano Sforza to repay to Salaì a debt of that exact amount over the course of four years. What of the rest? Leonardo never asks for it— but then, perhaps that’s why he leaves Salaì so little in his official will. When your love is a criminal offense, the best way to provide a future for your life partner is to go a bit off the books.

Leonardo sent his servant Salaì on an errand, that’s all. Isn’t that what you do with servants?

Salaì heads home, never to return to France. For his “good and kind services”, he inherits half of a vineyard (not even the whole thing! smirk the gossips) and a house in Milan... at least so far as official records are concerned. For his part, Melzi inherits the entirety of the maestro’s life work, as well as the distinction of being the most faithful, the most devoted, the only one to stay right up to the end. Once again, the distinction is emphasized heavily by modern chroniclers as proof of inner character.

Melzi v. Salaì will outlive its two namesakes by five centuries.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

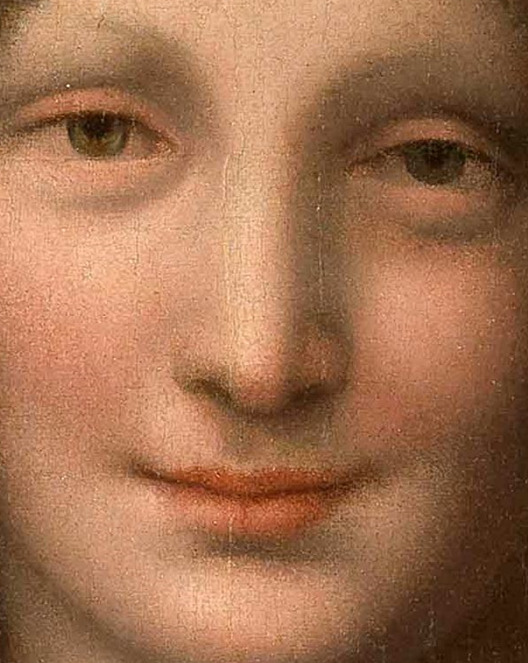

11. Boy Magdalen

He was ten years old when he became an apprentice, going straight from his parents’ house to Leonardo’s atelier on the Magdalen’s Day. To be accepted there was highly prestigious and would not have happened if he’d lacked talent. Despite a rocky start (no doubt fueled by a longing for home), he thrived— due in no small part to his maestro, who related deeply with him and helped him to channel his confusion into a lifetime of creativity and love.

That’s one way to put it.

Sticky-fingered, high-handed, mediocre, spoiled, petulant, scheming, greedy, faithless, irascible, thieving, gold-digging, chancer, scammer, reprobate, troublemaker, urchin, gigolo, swindler, trickster, forger, freeloader, parasite.

That’s another way.

Throwing shade at Salaì is practically a cottage industry. Historians and fiction writers have taken this innocent (if unruly) child, cherished (if underaged) lover, and loyal (if controversial) life partner and turned him into an all-purpose antagonist, the bane of a great artist’s life. They make no allowance for their subject’s tender age or confusing circumstances; they will not permit him to grow or change.

All because of four words – ladro, bugiardo, ostinato, ghiotto – used to describe him when he was ten.

The Magdalen herself would understand this child perfectly.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

12. One Last Drawing

Salaì cannot answer for himself. But history can, and so can Leonardo da Vinci.

In the British Royal Collection, there is a black chalk drawing of a curly-haired youth. Dated 1518, it is almost identical to a study drawn perhaps two decades earlier, in red ink. Both are commonly considered portraits of Salaì, who – given the timing – was most likely far away when Leonardo da Vinci picked up his stick of black chalk.

To me, this says that the aged and infirm Leonardo was still thinking about his familiar, enough that he felt compelled to draw – from pure memory – a little ikon to gaze at while the Little Devil was away.

Is that testimony enough?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources & Resources

Bibliography

Isaacson, Walter (2017). Leonardo da Vinci. New York: Simon & Schuster

Lacombe, Benjamin and Echegoyan, Paul (2015). Leonardo & Salaì. Berlin: Verlagshaus Jacoby & Stuart

Lewis, Ben (2019). The last Leonardo: the secret lives of the world’s most expensive painting. New York: Random House Publishing.

Nicholl, Charles (2004). Leonardo da Vinci: flights of the mind. New York: Viking Penguin Books

Richter, Jean Paul (1883). The literary works of Leonardo Da Vinci, vols. 1 & 2. London: S. Low, Searle & Rivington. Digitized by Getty Research Institute.

Stiles, Raymond Somers (1970). The sublimations of Leonardo da Vinci, with a translation of the Codex Trivulzianus. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press

Suh, H. Anna, ed. (2005). Leonardo’s notebooks: writing and art of the great master. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

Turner, Jane, ed. (2006) Benezit Dictionary of Artists.Paris: Éditions Gründ

Wasserman, Jack (1970). Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (Vol. 19, “Gian Giacomo Caprotti”). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana - Volume 19 (1976)

Zecchini, Maurizio (2013). Leonardo da Vinci and Gian Giacomo Caprotti called Salaì: the enigma of a painting. Venice: Marsilio Editori

Resource & Article Links

http://monalisa.org/2012/09/08/the-travel-journal-of-antonio-de-beatis

http://monalisa.org/the-earlier-version/provenance-2/

https://tourdetravoy.wordpress.com/2020/08/26/investigating-the-route-leonardo-da-vinci-may-have-used-to-travel-from-rome-in-italy-to-amboise-in-france-in-1516/

https://pushkinmuseum.art/data/fonds/europe_and_america/j/1001_2000/zh_2667/index.php

https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/leonardo-da-vinci-a-life-in-drawing/walker-art-gallery-liverpool/the-head-of-a-youth-in-profile

http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2007/important-old-master-paintings-and-european-works-of-art-n08282/lot.34.html

https://intro819.wordpress.com/2017/11/12/chiaroscuro-a-study-of-light-and-darkness-as-fact-and-fiction-in-conceiving-vertigos-the-private-lives-of-leonardo-da-vinci/

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/16/the-secret-lives-of-leonardo-da-vinci

https://www.finestresullarte.info/opere-e-artisti/salai-gian-giacomo-caprotti-allievo-ladro-e-bugiardo-di-leonardo-da-vinci

http://monalisa.org/2013/03/19/salai-and-the-two-paintings/

https://www.artmarketmonitor.com/2020/10/30/rare-penitent-magdelene-by-leonardo-disciple-to-sell-in-paris/

https://en.ivankrutoyarov.com/2013/02/mona-lisa-copies.html

https://www.fromoldbooks.org/Richter-NotebooksOfLeonardo/

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

3. The Familiar

That Leonardo regards Gian Giacomo as more than only a servant is evident in his treatment. I fed you with milk like my own son, he will one day write. Clearly he’s forgiven all the broken glass and puddles of spilt wine.

Henceforth, every time Gian Giacomo disgraces himself, the maestro banishes him to the corner— then turns around and rescues him from it, as he might like to be rescued himself. Fettered by the need to succeed, Leonardo can’t afford to épater la bourgeoisie. But Gian Giacomo, with his special genius for mayhem, can.

After a while, it’s a wonder they get invited anywhere at all.

But Gian Giacomo’s restlessness is not all for show. His behavior – throwing tantrums, playing pranks, vexing fellow pupils, pilfering anything not nailed down – speaks to his tremendous inner turmoil. Leonardo treats his edgy young friend with superhuman patience. Again, he knows firsthand the confusion of a child sent away from home. And perhaps he alone appreciates what he has on his hands: not a famiglio but a familiar, a juvenile daemon who – if understood and nurtured – might aid him in his own creative sorcery.

Soon he’s calling Gian Giacomo by a new name: Salaì, my little devil.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

5. Beauty, Innocent

Cellini leaves one task off his curriculum: modeling. It’s a practice which requires stillness, concentration, and obedience— admittedly, traits not commonly associated with Salaì.

Surprisingly, he’s a natural—what Elizabeth von Arnim would call a “beauty-of-all-work”. Quick gesture drawings, figure studies, long-term sittings for portraits of gods and myths— he does it all, demonstrating levels of patience and focus no one could believe he possessed.

But it’s for Leonardo that Salaì truly shines. He is never more golden and glowing than when he sits for his maestro; his mischievous smile and benevolent eyes appear again and again in paint and pencil wielded by Leonardo’s hand. For his part, Leonardo alone perceives all that lies under the surface. He draws what he sees, as an artist must. But the way he draws what he feels— that's something different.

When did it happen?

No one can strictly say. The mid-16th century essayist Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo writes a fictional scene in which Leonardo cops to seducing a fifteen-year-old Salaì. Of course Lomazzo –born twenty years after Leonardo’s death – only has gossip to go by.

(But the fact that people were still gossiping decades later…)

How did it happen?

Was it coercive, abusive, exploitive? Was it hinged on power, or were both equal partners? Did a sudden, galvanizing crisis propel them together? Or was it a natural progression for two people who simply knew each other inside-out and back-to-front?

Why did it happen?

History and society cannot adequately answer this thorny question. A middle-aged man and a youth twenty-eight years his junior? And not just ANY youth, but the one he raised from a tender age?

We put up a mighty struggle to understand and account for it, but whatever we say, it’s no use.

Their union occurred. And it endured.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

10. The End

Salaì married in 1523 but had no children; he and his spouse Bianca didn’t have time. Despite indications that he was killed by French troops during the Four Years’ War, it’s the custom to ascribe his end either to a pointless street brawl or the mishandling of a weapon. On one hand, brutish; on the other hand, stupid—and of course he died intestate, leaving his young wife high and dry.

Typical Salaì.

His two older sisters squabbled over his estate, suggesting that it was something worth squabbling over. A list of his effects includes a number of paintings, one of which is intriguingly titled La Honda. From its high valuation, modern scholars assumed that this was the one and only La Gioconda.

Besides the Louvre’s version of La Gioconda (considered the original and purchased by François I for the Royal Collection in 1518), there are numerous copies attributed to the Leonardeschi and others, the Isleworth and Prado copies being the best-known. Disqualifying Salaì outright from even being capable of holding a paintbrush, more than one scholar has asserted that the Gioconda found in Salaì’s estate must have been the original… and that he (to put it bluntly) stole it.

Ladro, bugiardo…

6 notes

·

View notes