#Staatslabor

Text

Neue Spuren ins Wuhan-Labor

Compact:»Zitat des Tages: Der Verdacht ist nicht neu: Das Coronavirus stammt aus einem chinesischen Staatslabor in Wuhan. (…) Auffällig demnach auch: Das chinesische Militär war nach dem Virus-Ausbruch verdächtig früh in der Lage, Impfstoffteams aufzustellen.“ (Bild) „Nicht nur der Hamburger Nanowissenschaftler Roland Wiesendanger und der Jenaer Genetiker Günter Theißen legen plausibel dar, was gegen einen [...]

Der Beitrag Neue Spuren ins Wuhan-Labor erschien zuerst auf COMPACT. http://dlvr.it/SbzZYW «

0 notes

Text

Momentan dominieren Nachrichten über das Corona Virus die Medien. Die Daily Mail, Englands drittmeistverbreitetest Blatt, hat einen Artikel veröffentlicht, der darauf hinweist, das Corona Virus könnte in einem chinesischem Staatslabor entstanden sein. Basierend auf den Recherchen einer kürzlich erschienenen Forschungszeitung, die von Wissenschaftlern der Südchinesischen Technischen Universität veröffentlicht wurde, beschreibt der Artikel, dass das Virus vermutlich aus einem Labor in Wuhan stammt, nämlich der gleichen Stadt in der es erstmals identifiziert wurde. So nachdenklich das stimmen mag, die Tatsache, dass in der Gegend um Wuhan 42 Pharmaunternehmen ansässig sind und zahlreiche Biotechnologiefirmen, die Impfstoffe testen, wird in diesem Artikel nicht erwähnt. Weiter unter... https://www.dr-rath-foundation.org/2020/02/mainstream-uk-newspaper-publishes-article-suggesting-coronavirus-originated-in-laboratory/?lang=de&lang=de

0 notes

Text

A Complex Systems Theorist Explains How We Can Stop Coronavirus

The coronavirus pandemic is terrifying, but the solution is almost shockingly simple: We have to stop spreading the virus. In fact, if every single one of us took extreme social distancing measures and all of the sick were isolated, the curve we’ve been attempting to flatten would start plummeting toward zero.

While a gradual increase of COVID-19 cases that don't overwhelm healthcare followed by a decline is the goal of most public health agencies, basic math suggests we can actually turn exponential growth into exponential decline quite rapidly.

That’s the perspective that Yaneer Bar-Yam, a complex systems scientist who uses his specialized branch of mathematics study systems with many interactive components, like the stock market or social movements, is attempting to share with the world. His field’s basic premise is that all of the interdependencies within complex systems result in various "tipping points" and non-linear responses that are difficult to describe using simpler mathematical models. Over the last few months, Bar-Yam’s research organization, the New England Complex Systems Institute, has produced a series of coronavirus-focused white papers and guides that use the fundamental dynamics of a global pandemic to explain how to stop it.

In a short explanatory paper published online last month, Bar-Yam shows how pandemic spread is a simple problem of matrix multiplication. If you haven’t brushed up on your high school algebra in a while, a matrix is just a set of numbers arranged in rows and columns. In this case, the matrix is a “contagion network,” with columns and rows representing different individuals in a population. If two individuals interact enough to spread the disease, the value where their row and column meet is one. Otherwise, it’s zero.

In an ideal scenario where we know exactly who’s sick and who’s not, this contagion network could be multiplied by the list of people who are sick—a column of ones (sick) and zeros (healthy)—to produce a new list showing who’s likely to be sick during the next infectious period. Repeat the process over and over, and the illness either spreads or declines over time.

Critically, which of those two paths a virus follows, growth or decay, depends on the connectedness of the contagion network. Epidemiologists use a variable called R0, or the number of people each sick person infects, to describe this connectivity. If R0 is greater than 1, the number of sick will rise over time; if it’s less than one, the sick cases will shrink.

For now, estimates for COVID-19’s R value (called the “effective R” when it’s measured in populations) vary from around 2 to nearly 5. Either end of this range indicates a disease capable of spreading exponentially, which is exactly what we’re seeing in the US. But Bar-Yam’s math also demonstrates that if everyone on Earth were to self isolate for a couple of weeks — either alone, or with family members who also aren’t sick — COVID-19 would run out of new hosts to infect, and the pandemic would be brought under control. In a best-case scenario, effective R would fall to zero, and the illness could be eliminated in a single infectious period—in this case, about two weeks. In essence, instead of flattening the infection curve we’d be arresting it.

“The point is, it’s a multiplicative process and that creates an exponential growth or an exponential decline,” Bar-Yam told Motherboard. “The trick is if you have an exponentially growing disease, [switch it] to make it exponentially declining.”

Everyone eliminating all contact outside the home is impossible, of course, meaning we can’t realistically expect to vanquish the pandemic in just a couple of weeks. Health care workers risk infection simply by treating the sick; workers at elderly care facilities can’t easily abandon all physical interaction with their charges. We still need people working closely together in emergency services, running power plants and sanitation systems, and much more. Society can’t just cease to function.

But altering the contagion network in order to drive the effective R value down and change COVID-19’s trajectory from one of exponential growth to exponential decay is far from impossible. In fact, several countries have been able to do just that, most notably China, which was able to exponentially bend its infection curve toward zero through widespread testing and contact tracing, isolating the sick, and placing over fifty million citizens on lockdown. While China was seeing thousands of new cases of COVID-19 a day at the height of its outbreak in late January, on Monday it only saw one new local infection, at least according to official numbers from the National Health Commission.

“China’s taken criticism for coming in late,” said Shannon Bennett, a microbiologist at the California Academy of Sciences. “But when they did decide to do the social distancing they came in hard. Now they’re still getting new cases per day but fewer and fewer.”

However, if math tells us that countries with exponentially-rising caseloads can flatten and reverse their infection curves through collective action, other aspects of complex systems behavior lead to more sobering conclusions. For one, there’s the issue of time delay: It might take days to weeks for our responses to COVID-19 to start having a demonstrable impact. All the while, the number of cases is likely to keep rising fast.

Bar-Yam noted that even though China began taking aggressive control measures when there were fewer than 1,000 officially-reported cases in the country, by the time the outbreak was under control, the number of cases had topped 80,000.

As of Wednesday morning, The New York Times’ database indicated nearly 6,000 coronavirus cases in the United States, but Bennet and other experts have said that number is likely a severe underestimate due to inadequate testing. Unfortunately, this suggests that if the U.S. took immediate and radical nationwide action—as we saw the Bay Area do yesterday, when officials ordered nearly 7 million people to go into a near-lockdown—the scale of our outbreak would still likely be considerably worse than China’s.

“I would definitely say we are on the exponential part of the curve,” Bennett told Motherboard. “The power function of that exponential increase I would say is still uncertain, and certainly hampered in its estimation by the fact that we have a mess going on with under-testing.”

Complex systems also have tipping points that cause them to go through “phase changes,” as Danny Buerkli, the co-founder of Swiss government innovation lab Staatslabor, noted in a recent blog post on how this branch of math is relevant to coronavirus. In this case, a tipping point might be when hospitals run out of beds or critical equipment, forcing the entire healthcare system to go into triage mode.

“We’ve seen the [health care system] overload happening in China, Italy, possibly elsewhere,” Buerkli told Motherboard. “It’s misleading to think that just because everything is OK now it will be in the future."

In the U.S., we (hopefully) still have time to prevent COVID-19 from crossing a dangerous tipping point where the healthcare system is overwhelmed. But the clock is ticking. Bennett noted the importance of rolling out more widespread testing immediately; Bar-Yam, meanwhile, emphasizes the role of personal behavior and individual responsibility through aggressive social distancing, practicing good hygiene, and self-isolating at the first sign of symptoms. Businesses also have a key role to play by telling their employees work from home or providing paid time off (a challenge many companies aren’t exactly living up to).

All of these measures, Bar-Yam says, will help to weaken the contagion network and steer us onto a new, far less terrifying trajectory.

“In our current context, the network is connected everywhere and gets transited very rapidly,” he said. “But it’s possible by changing how people behave to radically prune that network."

A Complex Systems Theorist Explains How We Can Stop Coronavirus syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

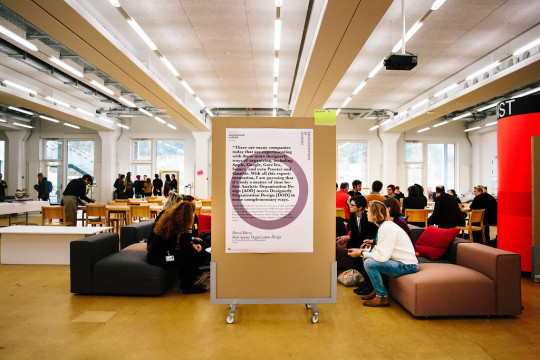

What went on at the Design in Organizations Symposium

Diverse speakers from varied backgrounds, queries and insights into emerging phenomena, and an explorative approach: as Richard Buchanan of Case Western University’s Design and Innovation Department deftly summarized in his closing keynote, the Design in Organizations Symposium was a “conference of discovery”.

Held at the Viscosistadt building of the Lucerne School of Art and Design, the first half of the two-day gathering was a collaborative whirlwind with leaders from business, academia, government, and the social sector sharing their perspectives on the integration of design in their respective fields.

The day was opened and lead by Sabine Junginger, Head of the Competence Center for Design and Management at the Lucerne School of Art and Design and Fellow at the Hertie School of Governance. The Competence Center, the hosts of the Symposium, is a research division of the HSLU focused on investigating, developing, and applying design methodologies to support human-centered innovation in organizations. They focus largely on design management for social innovation, public sector development, and organizational change, all of which aspects were represented in Thursday’s activities. Participants heard from an internationally-acclaimed array of experts including Dr. Xiangyan Xin, PhD, of the Jiangnan University School of Design; Dr. Martin Vogelsang of the German National Advisory Board for Impact Investing and the EVPA; Alenka Bonnard of Staatslabor Bern; Prof. Dr. Lorenz Herfurth of Glasgow School of Art; Caroline Paulick-Thiel of Politics for Tomorrow; Kaja Tooming Buchanan of Tongji University in Shanghai; Peter Wirz of Vetica, Catalina Jossen Cardozo of By Maria, and André Gassmann of Gemeinde Emmen.

Through engaging discussion of disparate-seeming contexts and projects, a number of themes emerged. Whether in education, government, social enterprise, or the private sector, there is a need for design to empower, lead, and evolve organizations moving into the future.

Dissemination: Sharing, Educating & Empowering

Often in Design Management, we speak about being advocates for design within organizations. This is based on the assumption that design is largely something new, foreign, and unlikely to be accepted easily. The disadvantages of such a mindset are obvious, but conversations during the Symposium reminded us of an important point. In a number of her papers, Sabine Junginger has urged design professionals (especially in the public sector) to remember: design activities are already going on throughout organizations, with or without professional designers. The people involved are recognizing needs, solving problems, and iterating solutions every day without acknowledging these as design activities. As Jan-Erik Baars is known to put it, “everyone designs, they just might not know it yet.”

So if everyone “designs”, what is the role of designers or design managers? As I stated in a panel discussion with Jan-Erik Baars and André Gassmann, I believe this makes design management expertise more relevant, not less. Design professionals catalyze these activities, giving a voice to ‘silent design’ and increasing the quality and efficiency of improvements. By bringing awareness and support to otherwise unconscious design activities, organizations can tap into their innovative potential.

This is in part about educating, but it’s more about empowerment. Education implies an imbalance: a divide between those with information and those without. To mediate this, we should appreciate our role as respectful and curious outsiders, and never seek to teach, without striving to learn from others as well. In the long-term, these practices can help build the trust necessary for collaborative growth.

As Enrique Martinez put it when describing his work at the US Office of Personnel Management’s Innovation Lab: when it comes to dissemination, we should aim to increase design literacy to the point that we make ourselves obsolete. Everyone has creative and transformative abilities. It is the job of design managers to remove barriers to that expression and create an environment where everyone can contribute. We must make hope accessible, and then step back and, as Priscilla Chueng-Nainby eloquently put it, “hold the space for change”.

Leadership: Purposeful Boundaries, Choices & Responsibilities

Both design and management are functions that determine “what” needs to be done. In determining this, they are trusted to give professional advice as to “how” projects and organizations should develop, and this inherently sets boundaries in order to direct future developments. Traditionally, management has dictated what should be done, and design has been concerned with how. While both of these activities involve narrowing options and defining an optimal direction, design had focused on the more physical and concrete aspects of improvement. However, as management sees the value of purpose-driven business, and as design moves from a Tactical Driver to an Organizational and Strategic one, both disciplines are starting to answer “why”.

We know that purpose-driven organizations have an easier time attracting talent, benefit from increased productivity, and enjoy improved resilience. Models like the Benefit Corporation and the social enterprise may well become more prevalent as we use our businesses not just to reap financial wealth, but to contribute solutions to the world’s many pressing problems. Their blend of traditionally disparate organizational formats (non-profit and for-profit) mirrors the kind of interdisciplinary line-blurring that Design Management often works to support, and evidences the increasingly collaborative, networked way of working we may do more of in the future.

Interestingly, the as the distinctions between disciplines fade and the edges of organizations blur, different boundaries have become much more important: those that define why an organization exists, what it is here to do, and which lines it will not cross. In addition to having a significant purpose, fostering cultures in which ethical discourse is valued and impactful can assist in this. Organizations must become proactive about ethics, Richard Buchanan said, and human-centered management should take a proactive role in realizing that. After all, he reminded us, we cannot talk about “sustainability” without defining what it is we want to sustain.

Fortunately, design practice has provided us with many tools we can apply to create more ethical organizations. In DMI for instance, we learn how to engage others in open-ended discussion (Ethnographic Conversation in Design Research), how to translate triple-bottom line needs and key organizational competencies into an actionable strategy (from Strategic Branding to Project Management), and how to build organizations optimized to follow through on that (Organizational Design). In this way, Design Managers are uniquely prepared to contribute to the organizations of the future. Wherever they find themselves, Design Managers should be a voice for people and planet, as well as profit. In taking more responsibility for our actions, as designers, design managers, and organizations, we can move towards true leadership.

Evolution: Iteration, Design-Being, and Continuing Prerogatives

In these times of accelerating change, the combination of guiding purpose and empowered evolution is the best-case-scenario for business. To be successful in such an environment, organizations must have both clear guiding principles and the ability to adapt to change. While the practices described in the last section help with the former, the tools we use to foster design competencies in organizations explained in the first section help with the latter. It is the synergy of these that allow for “problem-solution co-evolution” over time: “Design Being”.

Even as we move into dialectic design leadership though, we must not forget our essence. Many shared stories of promoted designers forced to conform to business as usual and losing their unique value in the process. We have a responsibility to stay true to our roots. Effective communications and innovative solutions: these, Richard Buchanan reminded us, are the foundations of design. The benefits of effective, human-centered problem-solving at any point in the efforts described in this paper is evident, but clear, compelling communication is also vital to succeeding at any of the areas described. Both should remain key competencies for design managers going forward. [They also define the two tracks of our Design Management Bachelor’s Program...] Likewise, we must remain advocates of end users, environment, and even beauty, tackling challenges with both effectiveness and elegance.

While each can learn something from these findings, the sectors of business, academia, and government need not become the same. They are most effective when they complement each other and interact often, exchanging insights as was done at this Symposium.

---

140 years since the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences began offering art and design education, we are undeniably in a time when the definition and role of design is changing. It’s part of a continued evolution from singular, superficial, and authorial to holistic, collective, and consciously transformative.

Design is a way of actively engaging in the evolution of our reality, and well-managed design in organizations allows for those profound contributions at scale. As the power of design is distributed, it becomes less about “making hope visible” as Brian Collins memorably said, and more about making hope accessible, meaningful, and actionable for all.

This is no small thing. It is a remarkable opportunity that comes with both transformative challenges and significant responsibilities. Still, one thing is certain: there is much work to do, plenty to learn, and far more left to discover.

---

This post was written by DMI Third Year Anastasia Linn. Those interested in the event can find more pictures from the Symposium by Michael Fund Photography here.

#designmanagement#designeducation#DesignLeadership#Education#FutureofWork#Leadership#Innovation#Cocreation#Codesign#TransitionalDesign#Luzern#HSLU#DesignResearch#DesignThinking#Collaboration

0 notes