#Nina Hedenius

Photo

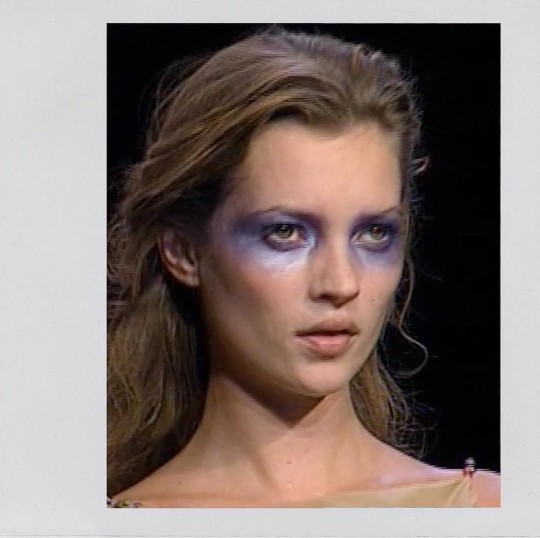

Det speglar i mitt öga (Nina Hedenius, 1992)

#Det speglar i mitt öga#Nina Hedenius#My Eye Is Reflecting#quote#memory#eyes#eye#cry#Det speglar i mitt oga#1992

568 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gubben i stugan (Nina Hedenius, 1995)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nära jorden, nära skogen (Nina Hedenius, 1984)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nära jorden, nära skogen

— Nina Hedenius, 1984

“Near The Earth, Near The Forest” is a poetic documentary about Man’s relationship to Nature, set in the Swedish region of Bergslagen.

0 notes

Photo

The Old Man in the Cottage (1996,Nina Hedenius)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nära jorden, nära skogen (Nina Hedenius, 1984) / Kate Moss | Martine Sitbon S/S 1996

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nära jorden, nära skogen (Nina Hedenius, 1984)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 Mars 2021

Tisdag

Looking into stretching.

We watch an old Nina Hedenius documentary about farmers.

Sometimes I think my body wanted to work on a farm.

Like my grandmother and her sisters.

Instead I am looking at youtube videos about stretching.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Det speglar i mitt öga (Nina Hedenius, 1992)

#Det speglar i mitt öga#Nina Hedenius#Det speglar i mitt oga#My Eye Is Reflecting#feet#cat#cats#animals#1992#childhood

347 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gubben i stugan/The Old Man in the Cottage (1996)

Nina Hedenius

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_smHkqDb3D8

0 notes

Text

Why you gotta go and make things so political?

Feminists and likeminded folx are quite often accused of bringing politics into things unnecessarily. We are accused of being a killjoy, of ruining family dinners by disagreeing with the racist relative, etc. In the words of feminist theorist Sara Ahmed: “We become the problem by describing the problem.” (2017, 39). I’ve certainly done my fair deal of killing joy, both in life in general, and on this blog in specifically. Here I’ve brought politics into the Harry Potterbooks, A Song of Ice and Fire, His Dark Materials, etc (...several times for all of those). So why do I, and so many others insist on doing this? Well, that’s what I’m going to try to explain in this text.

From a more academic/scholarly point of view, a lot of different fields analyse gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class etc in works of fiction. For instance, Swedish literary and art scholars Linda Fagerström and Maria Nilsson writes this about analysing gender in mass media:

Every Swedish consumer of media consumes around six hours of media each day. Therefore, it is not surprising that media has a big influence on us. Our values and views on things like our rights and responsibilities in a democratic society are impacted by this. It is therefore central to ask how media portrays for instance men and women. It is highly likely that we are impacted by these portrayals, and the values that they carry with them. (2008, 25) [My translation]

Furthermore, as literary scholar Rita Felski writes, “(…) trying to hold literature and the social world apart is a Sisyphean task: however valiantly critics try to keep art pure, external meanings keep seeping in.” (2003, 12). As she also points out, many literary critics try to look at the context in which a literary work was written, why would that not involve analysing for instance gender? (ibid, 14). I could of course cite countless more texts that say similar things, but the point is that scholars from several different fields agree that gender and other social categories should be analysed in media, partly because they always influence media and partly because media influences us, the consumers.

Now, I want to look at a slightly different point. In the text that I previously cited by Rita Felski, she also writes about why critics might be hesitant to analyse specifically gender:

Yet if bringing in social contexts and meanings is part of business as usual in literary critics, why is there so much fuss about expanding this framework to include gender? One reason, I think, lies in the current challenge to the universality of art. This is the sticking point, the place where traditional critics and feminist critics often seem to be speaking different languages. While scholars have often looked at the social conditions that shape literature, they have also believed that it transcends those conditions. Great art speaks beyond its time and place; and, what is more, it speaks to everybody. Defying details of history and context, gender, ethnicity, or creed, it embodies quintessential truths. Literature is universal because it speaks to a common, shared humanity. Feminists, however, often have a hard time with this universality. They point to a very long history of equating the male with the universal and seeing the female as the special case. (2003, 14)

Now, Felski is of the opinion that art/literature can transcend its context, while it is still important to analyse that context. But what I want to focus on is this idea that by bringing in gender (or sexuality, race, ability etc) one disturbs the idea of universality. As Felski writes, many feminists have critiqued this idea. It is also a central part in what is often called “feminist science critique” (Grahm & Lykke 2015, 78). One aspect of this is questioning the idea that the male is universal and neutral. For example, researchers have noted that medical research often uses male patients, which skews results (ibid, 80). In the case of heart disease research, this has led to researchers missing differences in symptoms between men and women, leading to treatment not working optimally. Other gender researchers have argued for research (in this case mostly in social sciences and humanities) to have its starting point with those least privileged, not the opposite (ibid, 82). Yet again other researchers, perhaps most famously Donna Haraway, argue that it is important to be critical of the idea of the objective scientist (ibid, 87). Is it possible to be completely objective when we are all part of the world that we study? Haraway would say no, therefore the scientist must always consider their own position and how that might affect their analysis.

This transitions me into my next question: what is neutral and apolitical? In her book “Feminist theory: from margin to center” bell hooks writes that oftentimes white women presume that their experience (as women) is universal, and that political reforms that benefit them will benefit all women (1984, 2). She further points out that when black women have questioned this, they have been seen as a problem, a threat to the unity of feminist sisterhood. So, just as science and research oftentimes have a male bias, feminism has a white (and heterosexual, cisgender, middleclass, able bodied etc) bias. What we can learn from these perspectives then, is that what is deemed universal and neutral seems to be that which applies to the groups in society that has the most power. But what we can also learn is that when such norms are questioned, those doing the questioning are seen as the ones being political and/or a problem. As if it’s more political to argue for change than to argue for the status quo. Once again, I want to return to what Sara Ahmed writes: “when you expose a problem you pose a problem” (2017, 37). By not keeping quiet about what you perceive as an injustice you cause a scene, you make everyone uncomfortable by making them consider the political implications of what is being said, you become the problem. Not ignoring the problem or shrugging it off has consequences: “by not doing something we will be perceived as doing too much.” (Ahmed 2017, 36)

So, this is why I keep on insisting on being political. Because I believe that we can see our social world reflected in the fictional worlds we consume. Because I believe that those fictional worlds influence our social world(s). Because I believe that our social world is inherently political, and to ignore that is to assume that the status quo is neutral. Now, you don’t have to agree with my views or my analysis! But I’ll keep on writing them down. As Sara Ahmed writes, sometimes when you speak up you will cause unhappiness (2017, 258). People will label you as a killjoy, the bringer of unhappiness. Yet we must persist in pointing out these problems, and support others who do, because:

Audre Lord once wrote ‘Your silence will not protect you’ (1984a, 41). But your silence could protect them. And by them I mean: those who are violent, or those who benefit in some way from silence about violence. The Killjoy is testimony. (Ahmed 2017, 260)

My point is not that you must share my every opinion. Rather, my point is that not taking a stance is not neutral. Of course, no one has the energy to stand on the barricades of every cause all the time. That would be exhausting. I’m not advocating for that. I just want people to realise that most everything in life is political in some way, and to deny that is political as well. Sorry. So, yeah, I’ll keep on being political.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Durham University Press

Fagerström, Linda & Maria Nilsson. 2008. Genus, medier och masskultur. Malmö: Gleerup

Felski, Rita. 2003. Literature after Feminism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Grahm, Jessica & Nina Lykke. 2015. “Ontologi och epistemologi i feministiskt tänkande”, in Feministiskt tänkande och sociologi: Teorier, begrepp och tillämpningar, eds Hedenius, Anna, Sofia Björk & Oksana Shmulyar Gréen, 77-95. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB

hooks, bell. Feminist Theory from Margin to Center. Boston: South End press.

Note: I used the Grahm and Lykke text here because I happened to have that book on hand. If anyone wants a source in English about feminist science critique, I can recommend looking up work by for instance Sandra Harding, Lynda Birke, Karen Barad, and Donna Haraway.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Gubben i stugan | The Old Man in the Cottage (Nina Hedenius, 1996)

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Det speglar i mitt öga (Nina Hedenius, 1992)

#Det speglar i mitt öga#My Eye Is Reflecting#Det speglar i mitt oga#quote#image#Nina Hedenius#1992#eyes#eye#reflection

288 notes

·

View notes

Photo

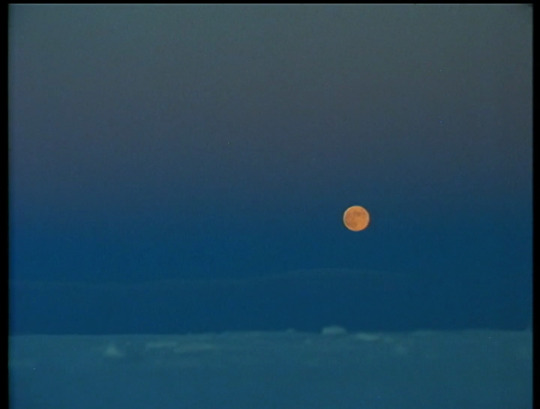

Det speglar i mitt öga (Nina Hedenius, 1992)

#Det speglar i mitt öga#Nina Hedenius#snow#long shot#landscapes#My Eye Is Reflecting#Det speglar i mitt oga#colour#blue#sun#sunset#1992#empty spaces#cloud#clouds#sky

335 notes

·

View notes