#Namwali Serpell

Text

richard siken crush: “litany in which certain things are crossed out” \\ josé saramago cain \\ richard snow and dirty rain \\ namwali serpell the furrows \\ ??

kofi

#richard siken#crush#litany in which certain things are crossed out#snow and dirty rain#on stories#on self#on identity#cain#jose saramago#osé saramago#the furrows#namwali serpell

849 notes

·

View notes

Text

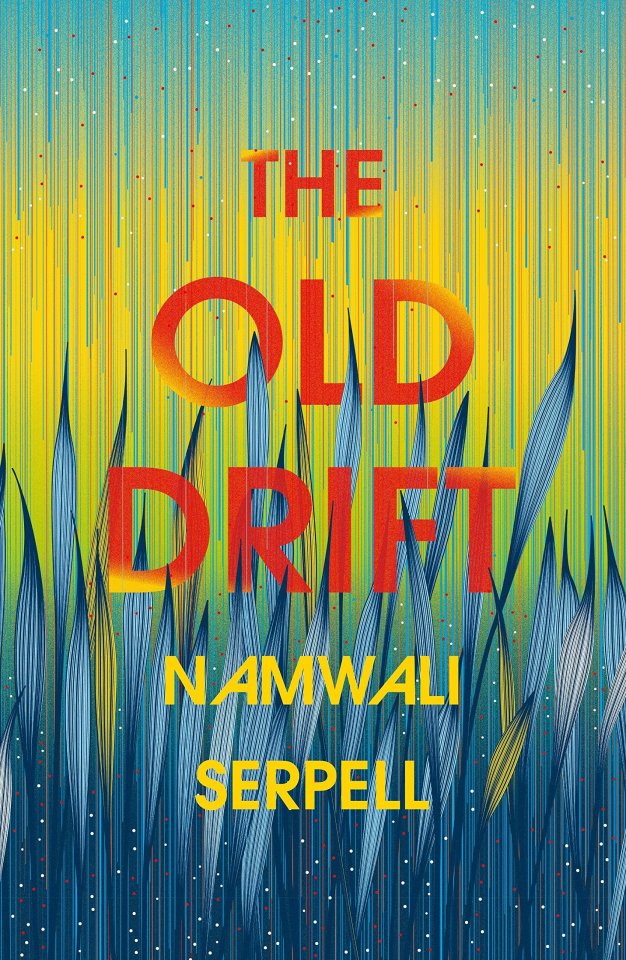

‘The Old Drift’ Is a Dazzling Debut Spanning Four Generations

By Dwight Garner

March 25, 2019

Namwali Serpell’s audacious first novel, “The Old Drift,” is narrated in small part by a swarm of mosquitoes — “thin troubadours, the bare ruinous choir” — who declare themselves “man’s greatest nemesis.”

They’re a pipsqueak chorus, a thrumming collective intelligence, a comic and subversive hive mind. They are here to puncture, if you will, humanity’s pretensions.

“The Old Drift” is an intimate, brainy, gleaming epic, set mostly in what is now Zambia, the landlocked country in southern Africa. It closely tracks the fortunes of three families (black, white, brown) across four generations.

The plot pivots gracefully — this is a supremely confident literary performance — from accounts of the region’s early white colonizers and despoilers through the worst years of the AIDS crisis. It pushes into the near future, proposing a world in which flocking bug-size microdrones are a) fantastically cool and b) put to chilling totalitarian purposes.

Serpell’s mosquitoes observe the dozens of wriggling humans in this novel, and they are distinctly unimpressed. We were here before you, they imply. We will be here long after you are gone. In the meantime, thanks for the drinks.

The reader who picks up “The Old Drift” is likely to be more than simply impressed. This is a dazzling book, as ambitious as any first novel published this decade. It made the skin on the back of my neck prickle.

Serpell seems to want to stuff the entire world into her novel — biology, race, subjugation, revolutionary politics, technology — but it retains a human scale. It is filled with love stories, greedy sex (“my heart twerks for you,” one character comments), pot smoke, comedy, inopportune menstruation, car crashes, tennis, and the scorching pleasure and pain of long hours in hair salons.

Serpell is a Zambian writer; she was born in that country and moved to the United States with her family when she was nine. She teaches literature at the University of California, Berkeley.

There’s a vein of magical realism in her work — one woman cries almost literal rivers, another has hair that covers nearly her entire body and that grows several feet a day — that will spark warranted comparisons to novels such as Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” and Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

Serpell does not try to charm her readers to death. Her men and women are not cute (except, sometimes, to each other), and they are not caricatures. Even the most virulent racists in “The Old Drift” aren’t one-dimensional.

Serpell is a pitiless and often very funny observer of people and of society. She describes polo as “that strange game that seems like a drunken bet about golf and horse riding.” A man on a leather sofa is commended for “expertly unlocking that complex apparatus — a clothed woman.”

She offers this definition of “history”: “the word the English used for the record of every time a white man encountered something he had never seen and promptly claimed it as his own, often renaming it for good measure.”

Here she is on a young white woman in Zambia: “She seemed both weak and imperious, helpless yet haughty. In a word: British.”

This is a matrilineal epic. It is packed with grandmothers, mothers, daughters. They are hardly placed on pedestals or lit by false, ennobling, autumnal light. They’re all struggling. Some drop out of school, steal or dabble with skin-whitening creams. Some open businesses, others turn to prostitution. Still others turn to protest. Nearly all are hoping to find love and, in the interim, to avoid being raped.

This book is intensely concerned with women’s bodies. Dissertations will surely be written about the multiple meanings of hair in this novel. We’ve learned too much from male writers about what it’s like to walk the planet guided and plagued by one’s reproductive apparatus. This novel, with wit and sensitivity, flips and revises that familiar script.

One young woman gets her period on her wedding day. Her friends, her family, the many guests — they’re all here. “All she wanted,” Serpell writes, “was to be at home in bed, curled in a ball, alone and quietly bleeding.”

Serpell is keenly interested in olfactory information. She lingers on people and places and scent. In one scene, a blind woman smells eucalyptus and knows she is nearly home. In another, a mother dislikes her daughter’s “new teenagery smell,” described as “a melony-lemony-biscuity scent that Adriana found both puerile and daunting.”

The plot of “The Old Drift” is not simple to unpack. The book begins, at the start of the 20th century, at a colonial settlement on the banks of the Zambezi River called the Old Drift. A dam is being constructed that will change many lives, a dam that some will wish to bring down.

The first women we meet, beginning around 1940, are: Sibilla, a white girl so unusually hirsute that at one point later in life she will be referred to as “an NGO for hair”; Agnes, a “pale, mad” and blind British girl who marries a black professor and engineer; and Matha, a bright girl whose prospects collapse after she becomes pregnant. She is this novel’s copious weeper, “the heartbreak queen of Kalingalinga.”

We get to know their daughters. One operates “Hi-Fly Haircuttery & Designs Ltd” (and perhaps a shadier business); another is a stewardess who once had artistic ambitions. One of these daughters has a long affair with a doctor who is working on a vaccine for H.I.V.

About a potential vaccine, we get shrewd snippets of dialogue like this one: “‘Beta version,’ Naila scoffed. ‘They should just say black version. They’re testing it on us.’”

The third generation goes on to work on microdrones, on further AIDS research and on political protest, seeking redress for the wrongs of history. One character also works on the vexing future of wearable technology — digital beadlike chips, implanted into the skin, that with the help of permanent tattoos of conductive ink turn one’s hands into approximations of smartphones.

“Government is controlling us,” one character says near the end of the novel. “And the worst part is — we chose this. We held our hands out to them and said PLEASE BEAD US!”

Serpell carefully husbands her resources. She unspools her intricate and overlapping stories calmly. Small narrative hunches pay off big later, like cherries coming up on a slot machine.

Yet she’s such a generous writer. The people and the ideas in “The Old Drift,” like dervishes, are set whirling. When that whirling stops, you can hear the mosquitoes again. They’re still out there.

They sound like tiny drones. They sound like dread.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“My identities don’t cancel or cross each other out: They enrich each other. Having a foot in multiple worlds can only be to the writer’s advantage.” Namwali Serpell discusses Black identity and double consciousness in relation to her new novel, The Furrows. For more, read the article: at.pw.org/HowItFelt

#Namwali Serpell#Fiction#Double Consciousness#Writing#Inspiration#Quote#Magazine#Archives#Writer's Block#Writer's Life#Novel#The Furrows

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Stranger Faces | Author: Namwali Serpell | Publisher: Transit Books (2020)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stranger Faces

By Namwali Serpell.

Design by Anna Morrison.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

no bones to bury, no truth to pin, no mysteries solved – only the inescapable rhythms of loss

Serpell is a terrific destabiliser, even at the level of the sentence. A room echoes with the “curbed bedlam” of sitcom laughter; commuters ignore each other in the “slotted indifference” of a train carriage. There are no tidy moral lessons at the end of her dissonant and time-contorting fable – no bones to bury, no truth to pin, no mysteries solved – only the inescapable rhythms of loss. “It’s like swimming,” she writes. “You stroke and kick to get to the outermost edge of the wave. You feel the momentum: go on go on go on. But always, something tugs you back into the scooped water, the furrows, those relentless grooves.”

— Beejay Silcox, from “The Furrows by Namwali Serpell review – bravura investigation of grief” (The Guardian, August 17, 2022)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond the creepiness, this pablum presumes reversibility. Yes, the political affects the personal, and both affect the literary. But having sex with the right person won’t change the world; reading the right book won’t either. Dark-washing characters won’t disappear race, nor will believing that brown kids are our future.

Yet this kind of magical thinking will no doubt continue to meet with success in an era obsessed with the conviction that we are all in a moment of racial reckoning. What Hamid’s novels actually offer isn’t education but recognition, a self-congratulatory reconfirmation of ideas like “migration is a death” and “race is a construct,” which are true enough but also truisms by now. Despite the horrors it has conjured, “the end of whiteness” is just another mantra of our current discourse; whether you are troubled by it or merely curious, Hamid is here to talk you through it.

— A World Without White People

#namwali serpell#a world without white people#books#writing#authors#politics#racism#ethnicity#sociology#philosophy#african americans

0 notes

Text

Men so weak that I have to break up with myself for them

Namwali Serpell: The Furrows (2022)

#namwali serpell: the furrows#relationships#womanhood#identity#coming of age (coa)#novel#quote#words

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

if you’re looking for something else to read, i did just finish the furrows by namwali serpell and thought of you the whole time because i think you’d really dig it! it’s playing around with The Gothic and The Sea and instability and unsettledness, and serpell has a great prose voice, very sinuous and surprising imo. also the book keeps getting read so extremely fucking badly by both goodreads and pro reviewers who keep going on about ~identity~ and grief but FAIL to connect these ideas to serpell’s thematic work around psychiatry and esp esp policing and the prison system and then say stupid things in their reviews like “i don’t understand why the second half of the book was there so i’m just going to talk about the themes in the first half”. anyway i think more people who know how to read and who know who angela davis is should read this book, and i think you’d really enjoy it!

ohhh i just checked out the summary and it definitely looks promising >:) will check it out, thank you!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Only a sister, an alternative self, could inspire such a sordid mix of disgust and envy.”

― Namwali Serpell, The Old Drift

Look at this amazing piece @aerart put together of Amelia and Carolyn (@naturescure). Sisters who would never stand back to back, so we thought something more opposite like the Queen Playcard was more fitting.

Thanks for doing this @zeehva!

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Moon. Art by Isa Carlin, from The Careful Tarot.

Where you sought an origin, you find a vast babble

which is also a silence: a chasm of smoke,

thundering. Blind mouth!

— Namwali Serpell, The Old Drift

The Moon is a card of fantasy and confusion. Unlike the Star, the Moon is not inherently good or gentle — but it is not necessarily dangerous or scary, either. It is simply the bewildering and fantastic sensation of being alone in a dark field under a wide open night sky.

The Moon might also hint at some sort of intuition or unseen force in your life. It may push you to accept something you have felt or believed but have never been able to prove.

Specifically, this card might refer to a haunting. It might refer to a situation of extreme confusion and uncertainty.

Keywords: uncertainty, fantasy

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: The Furrows | Author: Namwali Serpell | Publisher: Hogarth (2022)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Announcing our September/October issue!

Inside you’ll Renée H. Shea’s profile of Namwali Serpell, a special section on A Writer’s Education, including essays on finding permission to write from Deesha Philyaw, Melissa Chadburn, Paul Tran, and Elissa Schappell, and MFA application advice from Luis Jaramillo. Browse the full TOC!

#September#October#Magazine Cover#Poets#Writers#Inspiration#david sedaris#valeria luiselli#nonfiction#quotes

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New York Times Best Books of 2022: Fiction

The Candy House by Jennifer Egan

It’s 2010. Staggeringly successful and brilliant tech entrepreneur Bix Bouton is desperate for a new idea. He’s forty, with four kids, and restless when he stumbles into a conversation with mostly Columbia professors, one of whom is experimenting with downloading or “externalizing” memory. Within a decade, Bix’s new technology, Own Your Unconscious - that allows you access to every memory you’ve ever had, and to share every memory in exchange for access to the memories of others - has seduced multitudes. But not everyone.

In spellbinding linked narratives, Egan spins out the consequences of Own Your Unconscious through the lives of multiple characters whose paths intersect over several decades. Egan introduces these characters in an astonishing array of styles - from omniscient to first person plural to a duet of voices, an epistolary chapter, and a chapter of tweets. In the world of Egan’s spectacular imagination, there are “counters” who track and exploit desires and there are “eluders,” those who understand the price of taking a bite of the Candy House.

Checkout 19 by Claire-Louise Bennett

In a working-class town in a county west of London, a schoolgirl scribbles stories in the back pages of her exercise book, intoxicated by the first sparks of her imagination. As she grows, everything and everyone she encounters become fuel for a burning talent. The large Russian man in the ancient maroon car who careens around the grocery store where she works as a checkout clerk, and slips her a copy of Beyond Good and Evil. The growing heaps of other books in which she loses-and finds-herself. Even the derailing of a friendship, in a devastating violation. The thrill of learning to conjure characters and scenarios in her head is matched by the exhilaration of forging her own way in the world, the two kinds of ingenuity kindling to a brilliant conflagration.

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

Set in the mountains of southern Appalachia, this is the story of a boy born to a teenaged single mother in a single-wide trailer, with no assets beyond his dead father's good looks and copper-colored hair, a caustic wit, and a fierce talent for survival. In a plot that never pauses for breath, relayed in his own unsparing voice, he braves the modern perils of foster care, child labor, derelict schools, athletic success, addiction, disastrous loves, and crushing losses. Through all of it, he reckons with his own invisibility in a popular culture where even the superheroes have abandoned rural people in favor of cities.

Many generations ago, Charles Dickens wrote David Copperfield from his experience as a survivor of institutional poverty and its damages to children in his society. Those problems have yet to be solved in ours. Dickens is not a prerequisite for readers of this novel, but he provided its inspiration.

The Furrows by Namwali Serpell

Cassandra Williams is twelve; her little brother, Wayne, is seven. One day, when they're alone together, there is an accident and Wayne is lost forever. His body is never recovered. The missing boy cleaves the family with doubt. Their father leaves, starts another family elsewhere. But their mother can't give up hope and launches an organization dedicated to missing children.

As C grows older, she sees her brother everywhere: in bistros, airplane aisles, subway cars. Here is her brother's face, the light in his eyes, the way he seems to recognize her, too. But it can't be, of course. Or can it? Then one day, in another accident, C meets a man both mysterious and familiar, a man who is also searching for someone and for his own place in the world. His name is Wayne.

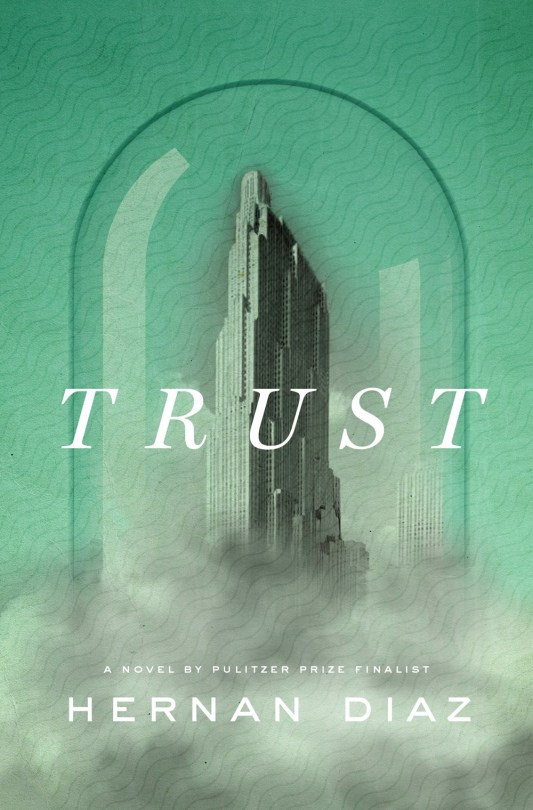

Trust by Hernan Diaz

Even through the roar and effervescence of the 1920s, everyone in New York has heard of Benjamin and Helen Rask. He is a legendary Wall Street tycoon; she is the brilliant daughter of eccentric aristocrats. Together, they have risen to the very top of a world of seemingly endless wealth. But the secrets around their affluence and grandeur incites gossip. Rumors about Benjamin's financial maneuvers and Helen's reclusiveness start to spread - all as a decade of excess and speculation draws to an end. At what cost have they acquired their immense fortune?

#fiction#best books#2022 reads#nyt#new york times#library books#book recs#book recommendations#reading recs#reading recommendations#TBR pile#tbr#to read#book blog#reading blog#book tumblr#booklr

3 notes

·

View notes